Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Fu-Manchu is trapped, cornered in London and cut-off from his resources, including the elixir vitae that grants him eternal life. But under the Thames, the devil doctor practices the dark art of sorcery, and it will be up to Nayland Smith and Scotland Yard to stop him. But Fu-Manchu may possess the key to victory, when he kidnaps Dr. Petrie's wife, Fleurette!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“Insidious fun from out of the past. Evil as always, Fu-Manchu reviles as well as thrills us.”

Joe R. Lansdale, recipient of the Horror Writers Association Lifetime Achievement Award

“Without Fu-Manchu we wouldn’t have Dr. No, Doctor Doom or Dr. Evil. Sax Rohmer created the first truly great evil mastermind. Devious, inventive, complex, and fascinating. These novels inspired a century of great thrillers!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Assassin’s Code and Patient Zero

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.”

James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th Century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction... at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.”

Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson... though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.”

Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in... For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”

K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro—or more precisely with Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Darth Vader, and Lex Luthor—in the imaginations of generations of readers and moviegoers.”

Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

“Exquisitely detailed... [Sax Rohmer] is a colorful storyteller. It was quite easy to be reading away and suddenly realize that I’d been reading for an hour or more without even noticing. It’s like being taken back to the cold and fog of London streets.”

Entertainment Affairs

“Acknowledged classics of pulp fiction... the bottom line is Fu-Manchu, despite all the huffing and puffing about sinister Oriental wiles and so on, always comes off as the coolest, baddest dude on the block.”

Comic Book Resources

“Undeniably entertaining and fun to read... It’s pure pulp entertainment—awesome, and hilarious and wrong. Read it.”

Shadowlocked

“The perfect read to get your adrenalin going and root for the good guys to conquer a menace that is almost supremely evil. This is a wild ride read and I recommend it highly.”

Vic’s Media Room

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIES

BY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE RETURN OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE HAND OF DR. FU-MANCHU

DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHU

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OFDR. FU-MANCHU

SAX ROHMER

TITAN BOOKS

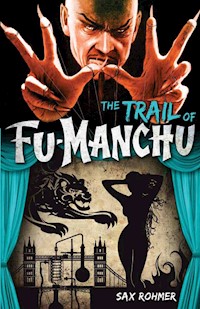

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686091

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686756

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First published as a novel in the UK by William Collins & Co. Ltd, 1934

First published as a novel in the US by Doubleday, Doran, 1934

First Titan Books edition: September 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2013 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

Frontispiece illustration by John Richard Flanagan, first appearing in Collier’s Weekly, April 28 1934. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu,” http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Contents

Chapter One: The Great Fog

Chapter Two: The Porcelain Venus

Chapter Three: Sterling’s Story

Chapter Four: Pietro Ambroso’s Studio

Chapter Five: P.C. Ireland is Uneasy

Chapter Six: Dr. Norton’s Patient

Chapter Seven: Lash Marks

Chapter Eight: Fog in High Places

Chapter Nine: The Tomb of The Demurases

Chapter Ten: The Mark of Kali

Chapter Eleven: Sam Pak of Limehouse

Chapter Twelve: London River

Chapter Thirteen: A Tongue of Fire

Chapter Fourteen: At Sam Pak’s

Chapter Fifteen: A Lighted Window

Chapter Sixteen: A Burning Ghat

Chapter Seventeen: The Game Flies West

Chapter Eighteen: “I Belong to China”

Chapter Nineteen: Rowan House

Chapter Twenty: Gold

Chapter Twenty-One: Gallaho and Sterling Set Out

Chapter Twenty-Two: Gallaho Runs

Chapter Twenty-Three: Fleurette

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Lacquer Room

Chapter Twenty-Five: Curari

Chapter Twenty-Six: Dr. Fu-Manchu

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Pit and the Furnace

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Tunnel Below Water

Chapter Twenty-Nine: At the Blue Anchor

Chapter Thirty: The Hunchback

Chapter Thirty-One: The Si-Fan

Chapter Thirty-Two: Iron Doors

Chapter Thirty-Three: Daughter of the Manchus

Chapter Thirty-Four: More Iron Doors

Chapter Thirty-Five: The Furnace

Chapter Thirty-Six: Dim Roaring

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Chinese Justice

Chapter Thirty-Eight: The Blue Light

Chapter Thirty-Nine: The Lotus Gate

Chapter Forty: A Fight to the Death

Chapter Forty-One: The Last Bus

Chapter Forty-Two: Nayland Smith Refuses

Chapter Forty-Three: Catastrophe

Chapter Forty-Four: At Scotland Yard

Chapter Forty-Five: The Match Seller

Chapter Forty-Six: Gallaho Explores

Chapter Forty-Seven: The Waterspout

Chapter Forty-Eight: Gallaho Brings Up the Rear

Chapter Forty-Nine: Waiting

Chapter Fifty: The Night Watchman

Chapter Fifty-One: Night Watchman’s Story

Chapter Fifty-Two: “I am Calling You”

Chapter Fifty-Three: Powers of Dr. Fu-Manchu

Chapter Fifty-Four: Gallaho Explores Further

Chapter Fifty-Five: Mimosa

Chapter Fifty-Six: Ibrahim

Chapter Fifty-Seven: A Call for Petrie

Chapter Fifty-Eight: John Ki

Chapter Fifty-Nine: Limehouse

Chapter Sixty: Dr. Petrie’s Patient

Chapter Sixty-One: The Crosslands’ Flat

Chapter Sixty-Two: Companion Crossland

About the Author

Appreciating Doctor Fu-Manchu

“I suggest that the beautiful figure which Preston saw was not constructed at Sèvres, but was Fleuette in that trance which only Fu-Manchu is able to induce.”

CHAPTER ONE

THE GREAT FOG

“Who’s there?”

P.C. Ireland raised his red lantern, staring with smarting eyes through moving wreaths of yellow mist. Visibility was nil. This was the great fog of 1934—the worst in memory.

No one replied—there was no sound.

The constable shook himself, and setting the lantern down at his feet, flapped his arms in an endeavor to restore circulation. This chilliness was not wholly physical. Something funny was going on—something he didn’t like. He stood quite still again, listening.

Three times he had heard that sound resembling nothing so much as the hard breathing of some animal, quite close to him in the fog—some furtive thing that crept by stealthily... And now, he heard it again.

“Who’s there?” he challenged, snatching up the red lamp.

None answered. The sound ceased—if it had ever existed.

Traffic had been brought to a standstill some hours before; pedestrians there were none. King Fog held the city of London in bondage. The silence was appalling. P.C. Ireland felt as though he was enveloped in a wet blanket from head to feet.

“I’ll go and have another look,” he muttered.

He began to grope his way up a short, semicircular drive to the door of a house. He had no idea what danger threatened Professor Ambroso, but he knew that he would be in for a bad time from the inspector if anyone entered or left the professor’s house unchallenged...

His foot struck the bottom of the three steps which led up to the door. Ireland mounted slowly; but not until his red lamp was almost touching the woodwork, could he detect the fact that the door was closed. He stood there awhile listening, but could hear nothing. He groped his way back to his post at the gate.

The police phone box was not fifty yards away; he would have welcomed any excuse to call up the station; to establish contact with another human being—to be where there was some light other than the dim red glow of his lantern, which, sometimes when he set it down, resembled, seen through the moving clouds of mist, the baleful eye of a monster glaring up at him.

He regained the gate and put the lantern down. He wondered when, if ever, he would be relieved. Discipline was all very well, but on occasions like this damned fog, when men who ought to have been in bed were turned out, a quiet smoke was the next best thing to a drink.

He groped under his oilskin cape for the packet, took out a cigarette and lighted it. He felt for the coping beside the gate and sat down. The fog appeared to be getting denser. Then in a flash he was on his feet again.

“Who’s there?” he shouted.

Stooping, he snatched up the red lantern and began to grope his way towards the other end of the semicircular drive.

“I can see you!” he cried, slightly reassured by the sound of his own voice—“Don’t try any funny business with me!”

He bumped into the half-open gate, and pulled up, listening. Silence. He had retained his cigarette, and now he replaced it between his lips. It was the blasted fog, of course, that was getting on his nerves. He was beginning to imagine things. It wouldn’t do at all. But he sincerely wished that Waterlow would come along to relieve him, knowing in his heart of hearts that Waterlow hadn’t one chance in a thousand of finding the point.

“Stick there till you’re relieved,” had been the inspector’s order.

“All-night job for me,” Ireland murmured, sadly.

What was the matter with this old bloke, Ambroso? He leaned against the gate and reflected. It was something about a valuable statue that somebody wanted to pinch, or something. Ireland found it difficult to imagine why anyone should want to steal a statue. The silence was profound—uncanny. To one used to the bombilation of London, even in the suburbs, it seemed unnatural. He had more than half smoked his cigarette when—there it was again!

Heavy breathing and a vague shuffling sound.

Ireland dropped his cigarette and snatched up his lantern. He made a surprising spring in the direction of the sound.

“Come here, damn you!” he shouted. “What the hell’s the game?”

And this time he had a glimpse of—something!

It rather shook him. It might have been a crouching man, or it might have been an animal. It was very dim, just touched by the outer glow of his lantern. But Ireland was no weakling. He made another surprising leap, one powerful hand outstretched. The queer shape sprang aside and was lost again in the fog.

“What the hell is it?” Ireland muttered.

Aware again of that unaccountable chill, he peered around him, holding the lantern up. He had lost his bearings. Where the devil was the house? He made a rapid calculation, turned about and began to walk slowly forward. He walked for some time in this manner, till his outstretched hand touched a railing. He had crossed to the verge of the Common.

He was on the wrong side of the road.

His back to the railings, he set out again. He estimated that he was half-way across, when:

“Help!” came a thin, muffled scream—the voice of a woman. “For God’s sake help me!”

The cry came from right ahead. P.C. Ireland moved more rapidly, grinding his teeth together. He had not been wrong—there was something funny going on. It might be murder. And, his heart beating fast, and all his training urging “hurry—hurry!” he could only crawl along. By sheer good luck he bumped into the half-open gate of the semicircular drive.

Evidently that cry had come from the house.

He moved forward more confidently—he was familiar with the route. Presently, a dim light glowed through the wet blanket of the fog. The door was open.

Ireland stumbled up the steps and found himself in a large lobby, brightly lighted. Fog streamed in behind him like the fetid breath of some monstrous dragon. There were pictures and statuettes; thick carpet on the floor; rugs and a wide staircase leading upwards. It was very warm. A coal fire had burned low in an open grate on one side of the lobby.

“Hello there!” he shouted. “I’m a police officer. Who called?”

There was no answer.

“Hi!” Ireland yelled at the top of his voice. “Is there anyone at home?”

He stood still, listening. A piece of coal dropped from the fire onto the tiled hearth. Ireland started. The house was silent—as silent as the fog-bound streets outside, and great waves of clammy mist were pouring in at the open door.

The constable put down his red lantern on a little coffee table, and began to look about him apprehensively. Then he walked to the foot of the stairs and trumpeted through cupped hands:

“Is there anyone there?”

Silence.

He was uncertain of his duty. Furthermore, this brightly lighted but apparently empty house was even more perturbing than the silence of the Common. A telephone stood on a ledge, not a yard from the coffee table. Ireland took up the instrument.

A momentary pause, during which he kept glancing apprehensively about him, and then:

“Wandsworth police station—urgent!” he said. “Police calling.”

CHAPTER TWO

THE PORCELAIN VENUS

That phenomenal fog which over a great part of Europe heralded and ushered in the New Year, was responsible for many things that were strange and many that were horrible. Amongst the latter the wreck of the Paris-Strasbourg express and the tragic crash of an Imperial Airways liner. The triumphant fog demon was responsible, also, for the present predicament of P.C. Ireland.

A big car belonging to the Flying Squad of Scotland Yard, and provided with special fog lights, stood outside Wandsworth police station. And in the divisional-inspector’s office a conversation was taking place which, could P.C. Ireland have heard it, would have made that intelligent officer realize the importance of his solitary vigil.

Divisional-inspector Watford was a gray-haired, distinguished looking man of military bearing. He sat behind a large desk looking alternately from one to the other of his two visitors. Of these, one, Chief-inspector Gallaho, of the C.I.D., was well known to every officer in the Metropolitan police force. A thick-set, clean-shaven man, of florid coloring and truculent expression, buttoned up in a blue overcoat and wearing a rather wide-brimmed bowler hat. He stood, resting one elbow upon the mantelpiece and watching the man who had come with him from Scotland Yard.

The latter, tall, lean, and of that dully dark complexion which tells of long residence in the tropics, wore a leather overcoat over a very shabby tweed suit. He was hatless, and his close-cropped, crisply waving gray hair excited the envy of the district inspector. His own hair was of that color but had been deserting him for many years. The man in the leather overcoat was smoking a pipe, and restlessly walking up and down the office floor.

The divisional inspector was somewhat awed by his second visitor, who was none other than ex-Assistant Commissioner Sir Denis Nayland Smith. Something very big was afoot. Suddenly pulling up in front of the desk, Sir Denis took his pipe from between his teeth, and:

“Did you ever hear of Dr. Fu-Manchu?” he jerked, fixing his keen eyes upon Watford.

“Certainly, sir,” said the latter, looking up in a startled way. “My predecessor in this division was actually concerned in the case, I believe, a number of years ago. For my own part”—he smiled slightly—“I have always regarded him as a sort of name—what you might term a trade-mark.”

“Trade-mark?” echoed Nayland Smith. “What do you mean? That there’s no such person?”

“Something of the kind, sir. I mean, isn’t Fu-Manchu really the name for a sort of political organization, like the Mafia—or the Black Hand?”

Nayland Smith laughed shortly, and glanced at the man from Scotland Yard.

“He is chief of such an organization,” he replied, “but the organization itself has another name. There is a Dr. Fu-Manchu—and Dr. Fu-Manchu is in London. That’s why I’m here tonight.”

The inspector stared hard for a moment, and then:

“Indeed, sir!” he murmured. “And may I take it that there’s some connection between this Fu-Manchu and Professor Ambroso?”

“I don’t know,” Nayland Smith snapped, “but I intend to find out tonight. What can you tell me about the professor? He lives in your area.”

“He does, sir.” The inspector nodded. “He has a large house and studio on the North Side of the Common. We have had orders for several days to afford him special protection.” Nayland Smith nodded, replacing his pipe between his teeth.

“Personally, I’ve never seen him, and I’ve never seen any of his work. He’s a bit outside my province. But I understand that although he’s an Italian by birth, he is a naturalized British subject. What he wants protection for, is beyond me. In fact, I should be glad to know, if anyone can tell me.”

Sir Denis glanced at the Scotland Yard man.

“Bring the inspector up-to-date,” he directed; “he’s evidently rather in the dark.”

Watford, resting his arms on the table, stared at the celebrated detective, enquiringly.

“Well, it’s like this,” Gallaho began in a low, rumbling voice. “If it means anything to you, I’ll begin by admitting that it means nothing to me. Professor Ambroso has been abroad for some time supervising the making of a new kind of statue at the Sevres works, outside Paris. It’s a life-sized figure, I understand, and more or less colored. Since the matter was brought to my notice, I have been looking up newspaper reports and it appears that the thing has created a bit of a sensation in artistic circles. Well, the professor took it down to an international exhibition held in Nice. This exhibition closed a week ago, and the figure, which is called ‘The Sleeping Venus,’ was brought back to Paris, and from Paris to London.”

“Did the professor come along, too?”

“Yes. And in Paris he asked for police protection.”

“What for?”

“Don’t ask me—I’m asking you. The French sent a man down to Boulogne on the train in which the thing was transported—then we took over on this side. There’s a man on duty outside his house now, isn’t there?”

“Yes. And the fog’s so dense it’s impossible to relieve him.” Nayland Smith had begun to walk up and down again; but now:

“He can be relieved when the other car arrives,” he jerked, glancing back over his shoulder. “I should have pushed straight on, but there is someone I am anxious to interrogate. I have arranged for him to be brought here.”

That the speaker was in a state of high nervous tension, none could have failed to recognize. He was a man oppressed by the cloud of some dreadful doubt.

“That’s the story,” Gallaho added. “The professor and his statue arrived by the Golden Arrow on Friday evening, just as the fog was beginning. He had two assistants, or workmen—foreigners, anyway, with him—and he had hired a small lorry. A plain-clothes man covered the proceedings, and the case containing the statue arrived at the professor’s house about nine o’clock on Friday night, I understand.” Then, unconsciously he echoed the ideas of Police Constable Ireland. “What the devil anybody wants to steal a statue for, is beyond me.”

“It’s so far beyond me,” Nayland Smith said rapidly, “that I am here tonight to inspect that work of art.”

Watford’s expression was pathetically blank.

“It doesn’t seem to mean anything,” he confessed.

“No,” said Gallaho, grimly, “it doesn’t. It will seem to mean less when I tell you that we had a wire from the Italian police this evening—advising us that Professor Ambroso had been seen in the garden of his villa in Capri yesterday morning.”

“What?”

“Sort that out,” growled Gallaho. “It looks as though we’ve been giving protection to the wrong man, doesn’t it?”

“Good Lord!” Watford’s face registered the blankest bewilderment. “Is it your idea, sir—?” he turned to Nayland Smith—“I mean, you don’t think that Professor Ambroso—”

“Well,” growled Gallaho—“go ahead.”

“No, of course, if he’s been seen alive! Good Lord!” But again he turned to Sir Denis, who was pacing more and more rapidly up and down the floor. “Where does Fu-Manchu come in?”

“That’s a long story,” Smith replied, “and until I have interviewed the professor, or the person posing as the professor, I cannot be certain that he comes in at all.”

There was a rap on the door, and a uniformed constable came in.

“The other car has arrived, sir,” he reported to Watford, “and there’s a Mr. Preston here, asking for Sir Denis Nayland Smith.”

“Show him in,” said Watford.

A few moments later a young man came into the office bringing with him a whiff of the fog outside. He wore a heavy tweed overcoat and white muffler, and carried a soft hat He had a fresh-colored face and light blue, twinkling eyes—very humorous and good-natured. He sneezed several times, and smiled apologetically.

“My name is Nayland Smith,” said Sir Denis. “Won’t you please sit down?”

“Thank you, sir,” and Preston sat down. “It’s a devil of a night to bring a bloke out, but I’ve no doubt it’s very important.”

“It is,” Nayland Smith snapped. “I will detain you no longer than possible.”

Gallaho turned in his slow fashion and fixed his observant eyes upon the newcomer. Divisional-inspector Watford watched Nayland Smith.

“I understand that you were on duty,” the latter continued, “At Victoria on Friday when the Paris-London service known as the Golden Arrow, arrived?”

“I was, sir.”

“It is customary on this service to inspect baggage at Victoria?”

“It is.”

“One of the passengers was Professor Pietro Ambroso, accompanied by two servants or workmen, and having with him a large case or crate containing a statue. Did you open this case?”

“I did.” Preston’s merry eyes twinkled. He sneezed, blew his nose and smiled apologetically. “There was a detective on special duty who had traveled across with the professor, and who seemed anxious to get the job over. He suggested that examination was unnecessary. “But—” he grinned—“I wanted to peep at the statue. The professor was inclined to be peevish, but—”

“Describe the professor,” snapped Nayland Smith.

Preston stared in surprise for a moment, and then:

“He’s a tall old man, very stooped, with a white beard and mustache. Wears pince-nez, a funny black, continental cape coat, and a wide-brimmed black hat. He speaks with a slight Italian accent, and he’s very frightening.”

“Admirable thumb-nail sketch,” Nayland Smith commented, his penetrating stare fixed almost feverishly upon the speaker. “Thank God for a man who can see straight. Do you remember the color of his eyes?”

Preston shook his head, suppressing a sneeze.

“He seemed to be half blind. He peered, keeping his eyes nearly closed.”

“Good. Go on. Statue.”

Preston released the pent-up sneeze. Then, grinning in his cheerful way:

“It was the devil of a game getting the lid off,” he went on. “But I roped off a corner to keep the curious away, and had the thing opened. Whew!” he whistled. “I got a shock. The figure was packed in on a sort of rest—and there was a second glass lid. I had the shock of my life!”

“Why?” growled Gallaho.

“Well, I’d read about the ‘Sleeping Venus’ in the papers. But I wasn’t quite prepared for what I saw. Really—it’s uncanny, and if I may say so, a bit shocking.”

“In what way?” jerked Nayland Smith.

“Well, it’s the figure of a beautiful girl, asleep. It isn’t shiny, as I expected, hearing that it was made of porcelain—it looks just like a living woman. And it’s colored, to represent nature. I mean, finger nails and toe-nails and everything. By gosh!”

“Sounds worth seeing,” growled Gallaho.

Nayland Smith dived into some capacious pocket within the leather overcoat, and produced a large mounted photograph. He set it upright on the inspector’s desk, right under the lamp. Preston stood up and Gallaho approached the table. Wisps of fog floated about the room, competing for supremacy with the tobacco smoke from Nayland Smith’s briar. The photograph was that of a nude statue, such as Preston had described; an exquisite figure relaxed, as if in sleep.

“Do you recognize it?” jerked Nayland Smith.

Preston bent forward, peering closely.

“Yes,” he said, “that’s her—I mean, that’s it. At least, I think so.” He peered closer yet. “Damn it! I’m not so sure.”

“What difference do you notice?” Nayland Smith asked, eagerly.

“Well...” Preston hesitated. “I suppose it was the coloring that did it. But the statue was far more beautiful than this photograph.”

There came a rap on the door, and the uniformed constable came in.

“The third car has arrived, sir,” he reported to Watford, “and a Mr. Alan Sterling is here.”

CHAPTER THREE

STERLING’S STORY

Alan Sterling burst into the room. He was a lean young man, marked by an intense virility. His features were too irregular for him to be termed handsome, but he had steadfast Scottish eyes, and one would have said that tenacity of purpose was his chief virtue. His skin was very tanned, and one might have mistaken him for a young Army officer. His topcoat flying open revealing a much-worn flannel suit, and, a soft hat held in his hand, he was a man wrought-up to the verge of endurance. His haggard eyes turned from face to face. Then he saw Sir Denis, and sprang forward:

“Sir Denis!” he said, “Sir Denis—” and despite his Scottish name, a keen observer might have deduced from his intonation that Sterling was a citizen of the United States. “For God’s sake, tell me you have some news? Something—anything! I’m going mad!”

Nayland Smith grasped Sterling’s hand, and put his left arm around his shoulders.

“I am glad you’re here,” he said, quietly. “There is news, of a sort.”

“Thank God!”

“Its value remains to be tested.”

“You think she’s alive? You don’t think—?”

“I am sure she’s alive, Sterling.”

The other three men in the room watched silently, and sympathetically. Gallaho, alone, seemed to comprehend the inner significance of Sterling’s wild words.

“I must leave you for a moment,” Nayland Smith went on. “This is Divisional-inspector Watford, and Chief Detective-inspector Gallaho, of Scotland Yard. Give them any information in your possession. I shall not be many minutes.” He turned to Preston. “If you will give me five minutes’ conversation before you go,” he said, “I shall be indebted.”

He went out with Preston. Sterling dropped into the chair which the latter had vacated, and ran his fingers through his disordered hair, looking from Gallaho to Watford.

“You must think I am mad,” he apologized. “But I’ve been through hell—just real hell!”

Gallaho nodded, slowly.

“I know something about it, sir,” he said, “and I can sympathize.”

“But you don’t know Fu-Manchu!” Sterling replied, wildly. “He’s a fiend—a demon—he bears a charmed life.”

“He must,” said Watford, watching the speaker. “It’s a good many years since he first came on the books, sir, and if as I understand he’s still going strong—he must be a bit of a superman.”

“He’s the Devil’s agent on earth,” said Sterling, bitterly. “I would give ten years of my life and any happiness that may be in store for me, to see that man dead!”

The door opened, and Nayland Smith came in.

“Give me the details quickly, Sterling,” he directed. “Action is what you want—and action is what I’m going to offer you.”

“Good enough, Sir Denis.” Sterling nodded. He was twisting his soft hat between his hands. It became apparent from moment to moment, how dangerously overwrought he was. “Really—there’s absolutely nothing to tell you.”

“I disagree,” said Nayland Smith, quietly. “Odd facts pop up, if one reviews what seemed at the time to be meaningless. We have two very experienced police officers here and since they are now concerned in the case, I should be indebted if you would outline the facts of your unhappy experience.”

“Good enough. From the time you saw me off in Paris?”

“Yes.” Nayland Smith glanced at Watford and Gallaho. “Mr. Sterling,” he explained, “is engaged to the daughter of an old mutual friend, Dr. Petrie. Fleurette—that is her name—spent a great part of her life in the household of that Dr. Fu-Manchu, whom you, Inspector Watford, seem disposed to regard as a myth.”

“Funny business in the south of France, some months ago,” Gallaho growled. “The French press hushed it up, but we’ve got all the dope at the Yard.”

“Sir Denis and I,” Sterling continued, “went to Paris with Dr. Petrie and his daughter, my fiancée. They were returning to Egypt— Dr. Petrie’s home is in Cairo. Sir Denis was compelled to hurry back to London, but I went on to Marseilles and saw them off in the Oxfordshire of the Bibby Line.”

“I only have the barest outline of the facts, sir,” Gallaho interrupted. “But may I ask if you went on board?”

“I was one of the last visitors to leave.”

“Then I take it, sir, you waved to the young lady as the ship was pulling out?”

“No,” Sterling replied, “I didn’t, as a matter of fact, Inspector. I left her in the cabin. She was very disturbed.”

“I quite understand.”

“Dr. Petrie was on the promenade deck as the ship pulled out, but Fleurette, I suppose, was in her cabin.”

“The point I was trying to get at, sir, was this,” Gallaho persisted, doggedly, whilst Nayland Smith, an appreciative look in his gray eyes, watched him. “How long elapsed between your saying goodbye to the young lady in her cabin, and the time the ship pulled out?”

“Not more than five minutes. I talked to the doctor—her father— on deck, and actually left at the last moment.”

“Fleurette asked you to leave her?” jerked Nayland Smith.

“Yes. She was terribly keyed-up. She thought it would be easier if we said good-bye in the cabin. I rejoined her father on deck, and—”

“One moment, sir,” Gallaho’s growling voice interrupted again. “Which side of the deck were you on? The seaward side, or the land side?”

“The seaward side.”

“Then you have no idea who went ashore in the course of the next five minutes?”

“No. I am afraid I haven’t.”

“That’s all right, sir. Go ahead.”

“I watched the Oxfordshire leave,” Sterling went on, “hoping that Fleurette would appear; but she didn’t. Then I went back to the hotel, had some lunch, and picked up the Riviera Express in the afternoon, returning to Paris. I was hoping for a message at the Hotel Meurice but there was none.”

“Did Petrie know you were staying at the Meurice?” jerked Nayland Smith.

“No, but Fleurette did.”

“Where did you stay on the way out?”

“At the Chatham—a favorite pub of Petrie’s.”

“Quite. Go on.”

“I dined, and spent the evening with some friends who lived in Paris, and when I returned to my hotel, there was still no message. I left for London this morning, or rather—since it’s well after midnight—yesterday morning. A radio message was waiting for me at Boulogne. It had been dispatched on the previous evening. It was from Petrie on the Oxfordshire...” Sterling paused, running his fingers through his hair... “It just told me that Fleurette was not on board; urged me to get in touch with you, Sir Denis, and finally said the doctor was hoping to be transferred to an incoming ship.”

“A chapter of misadventures,” Nayland Smith murmured. “You see, we were both inaccessible, temporarily. I have later news, however. Petrie has effected the transference. He has been put on to a Dutch liner, due into Marseilles tonight.” The telephone bell rang. Inspector Watford took up the instrument on his table and:

“Yes,” he said, listened for a moment, and then: “Put him through to me here.”

He glanced at Nayland Smith.

“The constable on duty outside Professor Ambroso’s house,” he reported, a note of excitement discernible in his voice.

Some more moments of silence followed during which all watched the man at the desk. Smith smoked furiously. Sterling, haggard under his tan, glanced from face to face almost feverishly. Chief Detective-inspector Gallaho removed his bowler, which fitted very tightly, and replaced it at a slightly different angle. Then:

“Hello, yes—officer in charge speaking. What’s that?... ” The vague percussion of a distant voice manifested itself. “You say you are in the house? Hold on a moment.”

The inspector looked up, his eyes alight with excitement.

“The officer on duty heard a cry for help,” he explained; “found his way through the fog to the house; the door was open, and he is now in the lobby. The house is deserted, he reports.”

“We are too late!” It was Nayland Smith’s voice. “He has tricked me again! Tell your man to stand by, Inspector. Gather up all the men available and pack them into the second car. Come on, Gallaho. Sterling, you join us!”

CHAPTER FOUR

PIETRO AMBROSO’S STUDIO

Even the powerful searchlights attached to the Flying Squad car failed to penetrate that phenomenal fog for more than a few yards. Progress was slow. To any vehicle not so equipped it would have been impossible. A constable familiar with the districts walked ahead, carrying a red lantern. A powerful beam from the leading car was directed upon this lantern, and so the journey went on.

P.C. Ireland in the lobby of Professor Ambroso’s house learned the lesson that silence and solitude can be more terrifying than the wildest riot. His instructions had been to close the door but to remain in the lobby. This he had done.

When he found himself alone in that house of mystery, the strangest promptings assailed his brain. He was not an imaginative man, but sheer common sense told him that something uncommonly horrible had taken place in the house of Professor Ambroso that night.

The fire was burning low in the grate. There were some wooden logs in an iron basket, and Ireland tossed two on the embers without quite knowing why he took the liberty. Red tape bound him. Furtively he watched the stairs which disappeared in shadows, above. He was a man of action; his instinct prompted him to explore this silent house. He had no authority to do so. His mere presence in the lobby—since he could not swear that the cry actually had come from the house—was a transgression. But in this, at least, he was covered; the divisional inspector had told him to stay there. How did they hope to reach him, he argued. They would probably get lost on the way.

Now that the fog was shut out, he began to miss it. The silence which seemed to speak and in which there were strange shapes, had been awful, out there, on the verge of the Common, but the silence of this lighted lobby was even more oppressive.

Always he watched the stair.

Mystery brooded on the dim landing, but no sound broke the stillness. He began to study his immediate surroundings. There were some very strange statuettes in the lobby—queer busts, and oddly distorted figures. The paintings, too, were of a sort to which he was unused. The entire appointments of the place came within the category which P.C. Ireland mentally condemned under the heading of “Chelsea.”

One of the logs which he had placed upon the fire, and which had just begun to ignite, fell into the hearth. He started, as though a shot had been fired.

“Damn!” he muttered, “this place is properly getting on my nerves.”

He rescued the log and tossed it back into place. A cigarette was indicated. He could get rid of it very quickly, if the inspector turned up in person, which he doubted. He discarded his oilskin cape, and produced a little yellow packet, selecting and lighting a cigarette almost lovingly. There was company in a cigarette when a man felt lonely and queer. Always, he watched the stair.

He had finished his cigarette and reluctantly tossed the stub into the fire which now was burning merrily, when the sharp note of a bell brought him to his feet at a bound. It was the door-bell. P.C. Ireland ran forward and threw the door open.

A man in a leather overcoat, a gray-haired man, with piercing steely-blue eyes, stood staring at him.

“Constable Ireland?” he rapped.

There was unmistakable authority about the new arrival, and:

“Yes, sir,” Ireland replied.

Nayland Smith walked into the lobby, followed by Inspector Gallaho, a figure familiar to every officer in the force. There was a third man, a young, very haggard looking man. But Ireland barely noticed him. The presence of Gallaho told him that in some way which might prove to be profitable to himself, he had become involved in a case of major importance. Fog swept into the lobby. He stood to attention, recognizing several familiar faces, of brother constables, peering in out of the darkness.

“You heard a cry for help?” Nayland Smith went on. His mode of speech reminded the constable of a distant machine gun. “You were then at the gate, I take it?”

“No, sir.”

“Why not?” growled Gallaho.

“There was someone moving about in the fog, sir. When I challenged him, he didn’t answer—he just disappeared. At last, I got a glimpse of him, or it, or whatever it was.”

“What do you mean by ‘it’?” Gallaho demanded. “If you saw something—you can describe it.”

“Well, sir, it might have been a man crouching down on his hands and knees—you know what the fog is like—”

“You mean,” said Nayland Smith, “that you endeavored to capture this thing—or person—who declined to answer your challenge?”

“Thank you, sir; yes, that’s what I mean.”

“Did you touch him or it?” Gallaho demanded.

“No, sir. But I lost my bearings trying to grab him. I found myself nearly on the other side of the road by the Common, when I heard the cry.”

“Describe this cry,” snapped Nayland Smith.

“It was a woman’s voice, sir; very dim through the fog. And the words were ‘Help! For God’s sake help me!’ I thought it came from this house. I groped my way back, and when I reached the door, found it open. I’ve been here in the lobby, ever since.”

“You say it was a woman’s voice,” Sterling broke in. “Did it sound like a young woman or an old woman?”

“Judging from what I could make out through the fog, sir, I should say, a young woman.”

Sterling clutched his hair distractedly. He felt that madness was not far off.

Gallaho turned to Sir Denis.

“It’s up to you, sir. Do you want the house searched? According to regulations, we are not entitled to do it.”

His tone was ironical.

“Search it from cellar to attic,” snapped Nayland Smith. “Post a man at each end of the drive and split the others up.”

“Good enough, sir.” Gallaho returned to the open doorway. “How many of you have got lanterns—torches are no good in this blasted fog.”

“Two,” came a muffled voice, “and Ireland has a third.”

“The two men with lanterns are to stand at the ends of the drive. Anybody coming out—get him. Jump to it. The rest of you, come in.”

Four constables came crowding into the lobby.

“Isn’t there a garage?” snapped Nayland Smith.

“Yes, sir,” Ireland replied. “It opens on to the left side of the drive-in. But nothing has gone out of it tonight.”

“Have you any idea where the studio is?”

“Yes, sir. I’ve been on day duty here. It’s behind the garage—but probably, there’s a way through from the house.”

“Join me, Sterling,” said Nayland Smith. “Gallaho, allot a man to each of the four floors. Close the door again, and post a man in charge here, in the lobby.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Come with me, Ireland. You say the studio lies in this direction?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Come on, Sterling.”

They crossed the lobby, approaching a door on the left of the ascending staircase. Chief Detective-inspector Gallaho was readjusting his bowler. Police constables were noisily clattering upstairs, their torches flashing as they ran. The door proved to open on to a narrow corridor.

“Find the switch,” snapped Nayland Smith.

Ireland found it. And in the new illumination, queer paintings assailed their senses from the walls. There was a door at the further end of the passage. They opened it and found themselves in some dark, lofty place.

“There’s a switch, somewhere,” Nayland Smith muttered.

“I’ve found it, sir.”

The studio of Pietro Ambroso became illuminated.

To one not familiar with the Modern Art movement it must have resembled a nightmare. Those familiar with the phases of the celebrated sculptor could have explained that his mode of expression, which, for a time—indeed, for many years—had conformed to the school with which the name of Epstein is associated, had, latterly, swung back to the early Greek tradition—the photographic simplicity of Praxiteles. All sorts of figures and groups surrounded the investigators. That deplorable untidiness which seems to be inseparable from genius characterized the studio.

There were one or two earlier examples of ceramic experiments— strange figures in porcelain resembling primitive goddesses. But Nayland Smith’s entire attention was focussed upon a long, narrow box, very stoutly built, which lay upon the floor. In form, it bore an unpleasant resemblance to a coffin. Its lid was propped against the wall near by, and a sheet of plate glass, obviously designed to fit inside the crate, lay upon the floor. Quantities of cotton wool were scattered about. Nayland Smith bent and peered at the receptacle.

“This is the thing described by Preston,” he said. “Look—” He pointed. “There are the rests which he mentioned—not unlike those used in ancient Egypt for the repose of the mummy.”

He stared all around the studio.