Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Phoemixx Classics Ebooks

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

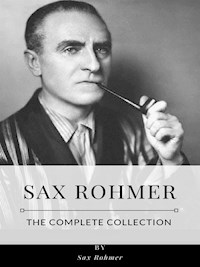

The Green Eyes of Bâst - Sax Rohmer - Sax Rohmer, better known as the author of the infamous Fu Manchu stories, wrote a number of paranormal mysteries, The Green Eyes of Bast being one written in 1920. The Green Eyes of Bast was written by Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward, known better under his pseudonym, Sax Rohmer. Sax Rohmer was a prolific eng novelist. He is best remembered for his series of novels featuring the master criminal Dr. Fu Manchu.Psychic investigator Dr. Damar Greefe is strolling home. It's been a tough day, assisting the police. During this stroll, he feels someone or something watching him -- but when he turns to see who it is, he faces only emptiness. Then he sees a cat staring at him, eyes as green as jade. But when he goes to investigate, the cat has disappears!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 371

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PUBLISHER NOTES:

Quality of Life, Freedom, More time with the ones you Love.

Visit our website: LYFREEDOM.COM

Chapter

1

I SEE THE EYES

"Good evening, sir. A bit gusty?"

"Very much so, sergeant," I replied. "I think I will step into your hut for a moment and light my pipe if I may."

"Certainly, sir. Matches are too scarce nowadays to take risks with 'em. But it looks as if the storm had blown over."

"I'm not sorry," said I, entering the little hut like a sentry-box which stands at the entrance to this old village high street for accommodation of the officer on point duty at that spot. "I have a longish walk before me."

"Yes. Your place is right off the beat, isn't it?" mused my acquaintance, as sheltered from the keen wind I began to load my briar. "Very inconvenient I've always thought it for a gentleman who gets about as much as you do."

"That's why I like it," I explained. "If I lived anywhere accessible I should never get a moment's peace, you see. At the same time I have to be within an hour's journey of Fleet Street."

I often stopped for a chat at this point and I was acquainted with most of the men of P. division on whom the duty devolved from time to time. It was a lonely spot at night when the residents in the neighborhood had retired, so that the darkened houses seemed to withdraw yet farther into the gardens separating them from the highroad. A relic of the days when trains and motor-buses were not, dusk restored something of an old-world atmosphere to the village street, disguising the red brick and stucco which in many cases had displaced the half-timbered houses of the past. Yet it was possible in still weather to hear the muted bombilation of the sleepless city and when the wind was in the north to count the hammer-strokes of the great bell of St. Paul's.

Standing in the shelter of the little hut, I listened to the rain dripping from over-reaching branches and to the gurgling of a turgid little stream which flowed along the gutter near my feet whilst now and again swift gusts of the expiring tempest would set tossing the branches of the trees which lined the way.

"It's much cooler to-night," said the sergeant.

I nodded, being in the act of lighting my pipe. The storm had interrupted a spell of that tropical weather which sometimes in July and August brings the breath of Africa to London, and this coolness resulting from the storm was very welcome. Then:

"Well, good night," I said, and was about to pursue my way when the telephone bell in the police-hut rang sharply.

"Hullo," called the sergeant.

I paused, idly curious concerning the message, and:

"The Red House," continued the sergeant, "in College Road? Yes, I know it. It's on Bolton's beat, and he is due here now. Very good; I'll tell him."

He hung up the receiver and, turning to me, smiled and nodded his head resignedly.

"The police get some funny jobs, sir," he confided. "Only last night a gentleman rang up the station and asked them to tell me to stop a short, stout lady with yellow hair and a big blue hat (that was the only description) as she passed this point and to inform her that her husband had had to go out but that he had left the door-key just inside the dog-kennel!"

He laughed good-humoredly.

"Now to-night," he resumed, "here's somebody just rung up to say that he thinks, only thinks, mind you, that he has forgotten to lock his garage and will the constable on that beat see if the keys have been left behind. If so, will he lock the door from the inside, go out through the back, lock that door and leave the keys at the station on coming off duty!"

"Yes," I said. "There are some absent-minded people in the world. But do you mean the Red House in College Road?"

"That's it," replied the sergeant, stepping out of the hut and looking intently to the left.

"Ah, here comes Bolton."

He referred to a stolid, red-faced constable who at that moment came plodding across the muddy road, and:

"A job for you, Bolton," he cried. "Listen. You know the Red House in College Road?"

Bolton removed his helmet and scratched his closely-cropped head.

"Let me see," he mused; "it's on the right—"

"No, no," I interrupted. "It is a house about half-way down on the left; very secluded, with a high brick wall in front."

"Oh! You mean the empty house?" inquired the constable.

"Just what I was about to remark, sergeant," said I, turning to my acquaintance. "To the best of my knowledge the Red House has been vacant for twelve months or more."

"Has it?" exclaimed the sergeant. "That's funny. Still, it's none of my business; besides it may have been let within the last few days. Anyway, listen, Bolton. You are to see if the garage is unlocked. If it is and the keys are there, go in and lock the door behind you. There's another door at the other end; go out and lock that too. Leave the keys at the depôt when you go off. Got that fixed?"

"Yes," replied Bolton, and he stood helmet in hand, half inaudibly muttering the sergeant's instructions, evidently with the idea of impressing them upon his memory.

"I have to pass the Red House, constable," I interrupted, "and as you seem doubtful respecting its whereabouts, I will point the place out to you."

"Thank you, sir," said Bolton, replacing his helmet and ceasing to mutter.

"Once more—good night, sergeant," I cried, and met by a keen gust of wind which came sweeping down the village street, showering cascades of water from the leaves above, I set out in step with my stolid companion.

It is supposed poetically that unusual events cast their shadows before them, and I am prepared to maintain the correctness of such a belief. But unless the silence of the constable who walked beside me was due to the unseen presence of such a shadow, and not to a habitual taciturnity, there was nothing in that march through the deserted streets calculated to arouse me to the fact that I was entering upon the first phase of an experience more strange and infinitely more horrible than any of which I had ever known or even read.

The shadow had not yet reached me.

We talked little enough on the way, for the breeze when it came was keen and troublesome, so that I was often engaged in clutching my hat. Except for a dejected-looking object, obviously a member of the tramp fraternity, who passed us near the gate of the old chapel, we met never a soul from the time that we left the police-box until the moment when the high brick wall guarding the Red House came into view beyond a line of glistening wet hedgerow.

"This is the house, constable," I said. "The garage is beyond the main entrance."

We proceeded as far as the closed gates, whereupon:

"There you are, sir," said Bolton triumphantly. "I told you it was empty."

An estate agent's bill faced us, setting forth the desirable features of the residence, the number of bedrooms and reception rooms, modern conveniences, garage, etc., together with the extent of the garden, lawn and orchard.

A faint creaking sound drew my glance upward, and stepping back a pace I stared at a hatchet-board projecting above the wall which bore two duplicates of the bill posted upon the gate.

"That seems to confirm it," I declared, peering through the trees in the direction of the house. "The place has all the appearance of being deserted."

"There's some mistake," muttered Bolton.

"Then the mistake is not ours," I replied. "See, the bills are headed 'To be let or sold. The Red House, etc.'"

"H'm," growled Bolton. "It's a funny go, this is. Suppose we have a look at the garage."

We walked along together to where, set back in a recess, I had often observed the doors of a garage evidently added to the building by some recent occupier. Dangling from a key placed in the lock was a ring to which another key was attached!

"Well, I'm blowed," said Bolton, "this is a funny go, this is."

He unlocked the door and swept the interior of the place with a ray of light cast by his lantern. There were one or two petrol cans and some odd lumber suggesting that the garage had been recently used, but no car, and indeed nothing of sufficient value to have interested even such a derelict as the man whom we had passed some ten minutes before. That is if I except a large and stoutly-made packing-case which rested only a foot or so from the entrance so as partly to block it, and which from its appearance might possibly have contained spare parts. I noticed, with vague curiosity, a device crudely representing a seated cat which was painted in green upon the case.

"If there ever was anything here," said Bolton, "it's been pinched and we're locking the stable door after the horse has gone. You'll bear me out, sir, if there's any complaint?"

"Certainly," I replied. "Technically I shall be trespassing if I come in with you, so I shall say good night."

"Good night, sir," cried the constable, and entering the empty garage, he closed the door behind him.

I set off briskly alone towards the cottage which I had made my home. I have since thought that the motives which had induced me to choose this secluded residence were of a peculiarly selfish order. Whilst I liked sometimes to be among my fellowmen and whilst I rarely missed an important first night in London, my inherent weakness for obscure studies and another motive to which I may refer later had caused me to abandon my chambers in the Temple and to retire with my library to this odd little backwater where my only link with Fleet Street, with the land of theaters and clubs and noise and glitter, was the telephone. I scarcely need add that I had sufficient private means to enable me to indulge these whims, otherwise as a working journalist I must have been content to remain nearer to the heart of things. As it was I followed the careless existence of the independent free-lance, and since my work was accounted above the average I was enabled to pick and choose the subjects with which I should deal. Mine was not an ambitious nature—or it may have been that stimulus was lacking—and all I wrote I wrote for the mere joy of writing, whilst my studies, of which I shall have occasion to speak presently, were not of a nature calculated to swell my coffers in this commercial-minded age.

Little did I know how abruptly this chosen calm of my life was to be broken nor how these same studies were to be turned in a new and strange direction. But if on this night which was to witness the overture of a horrible drama, I had not hitherto experienced any premonition of the coming of those dark forces which were to change the whole tenor of my existence, suddenly, now, in sight of the elm tree which stood before my cottage the shadow reached me.

Only thus can I describe a feeling otherwise unaccountable which prompted me to check my steps and to listen. A gust of wind had just died away, leaving the night silent save for the dripping of rain from the leaves and the vague and remote roar of the town. Once, faintly, I thought I detected the howling of a dog. I had heard nothing in the nature of following footsteps, yet, turning swiftly, I did not doubt that I should detect the presence of a follower of some kind. This conviction seized me suddenly and, as I have said, unaccountably. Nor was I wrong in my surmise.

Fifty yards behind me a vaguely defined figure showed for an instant outlined against the light of a distant lamp—ere melting into the dense shadow cast by a clump of trees near the roadside.

Standing quite still, I stared in the direction of the patch of shadow for several moments. It may be said that there was nothing to occasion alarm or even curiosity in the appearance of a stray pedestrian at that hour; for it was little after midnight. Indeed thus I argued with myself, whereby I admit that at sight of that figure I had experienced a sensation which was compounded not only of alarm and curiosity but also of some other emotion which even now I find it hard to define. Instantly I knew that the lithe shape, glimpsed but instantaneously, was that of no chance pedestrian—was indeed that of no ordinary being. At the same moment I heard again, unmistakably, the howling of a dog.

Having said so much, why should I not admit that, turning again very quickly, I hurried on to the gate of my cottage and heaved a great sigh of relief when I heard the reassuring bang of the door as I closed it behind me? Coates, my batman, had turned in, having placed a cold repast upon the table in the little dining-room; but although I required nothing to eat I partook of a stiff whisky and soda, idly glancing at two or three letters which lay upon the table.

They proved to contain nothing of very great importance, and having smoked a final cigarette, I turned out the light in the dining-room and walked into the bedroom—for the cottage was of bungalow pattern—and, crossing the darkened room, stood looking out of the window.

It commanded a view of a little kitchen-garden and beyond of a high hedge, with glimpses of sentinel trees lining the main road. The wind had dropped entirely, but clouds were racing across the sky at a tremendous speed so that the nearly full moon alternately appeared and disappeared, producing an ever-changing effect of light and shadow. At one moment a moon-bathed prospect stretched before me as far as the eye could reach, in the next I might have been looking into a cavern as some angry cloud swept across the face of the moon to plunge the scene into utter darkness.

And it was during such a dark spell and at the very moment that I turned aside to light the lamp that I saw the eyes.

From a spot ten yards removed, low down under the hedges bordering the garden, they looked up at me—those great, glittering cat's eyes, so that I stifled an exclamation, drawing back instinctively from the window. A tiger, I thought, or some kindred wild beast, must have escaped from captivity. And so rapidly does the mind work at such times that instinctively I had reviewed the several sporting pieces in my possession and had selected a rifle which had proved serviceable in India ere I had taken one step towards the door.

Before that step could be taken the light of the moon again flooded the garden; and although there was no opening in the hedge by which even a small animal could have retired, no living thing was in sight! But, near and remote, dogs were howling mournfully.

Chapter

2

THE SIGN OF THE CAT

When Coates brought in my tea, newspapers and letters in the morning, I awakened with a start, and:

"Has there been any rain during the night, Coates?" I asked.

Coates, whose unruffled calm at all times provided an excellent sedative, replied:

"Not since a little before midnight, sir."

"Ah!" said I, "and have you been in the garden this morning, Coates?"

"Yes, sir," he replied, "for raspberries for breakfast, sir."

"But not on this side of the cottage?"

"Not on this side."

"Then will you step out, Coates, keeping carefully to the paths, and proceed as far as the tool-shed? Particularly note if the beds have been disturbed between the hedge and the path, but don't make any marks yourself. You are looking for spoor, you understand?"

"Spoor? Very good, sir. Of big game?"

"Of big game, yes, Coates."

Unmoved by the strangeness of his instructions, Coates, an object-lesson for those who decry the excellence of British Army disciplinary methods, departed.

It was with not a little curiosity and interest that I awaited his report. As I sat sipping my tea I could hear his regular tread as he passed along the garden path outside the window. Then it ceased and was followed by a vague muttering. He had found something. All traces of the storm had disappeared and there was every indication of a renewal of the heat-wave; but I knew that the wet soil would have preserved a perfect impression of any imprint made upon it on the previous night. Nevertheless, with the early morning sun streaming into my window out of a sky as near to turquoise as I had ever seen it in England, I found it impossible to recapture that uncanny thrill which had come to me in the dark hours when out of the shadows under the hedge the great cat's eyes had looked up at me.

And now, becoming more fully awake, I remembered something else which hitherto I had not associated with the latter phenomenon. I remembered that lithe and evasive pursuing shape which I had detected behind me on the road. Even now, however, it was difficult to associate one with the other; for whereas the dimly-seen figure had resembled that of a man (or, more closely, that of a woman) the eyes had looked out upon me from a point low down near the ground, like those of some crouching feline.

Coates' footsteps sounded again upon the path and I heard him walking round the cottage and through the kitchen. Finally he reëntered the bedroom and stood just within the doorway in that attitude of attention which was part and parcel of the man. His appearance would doubtless have violated the proprieties of the Albany, for in my rural retreat he was called upon to perform other and more important services than those of a valet. His neatly shaved chin, stolid red countenance and perfectly brushed hair were unexceptionable of course, but because his duties would presently take him into the garden he wore, not the regulation black, but an ancient shooting-jacket, khaki breeches and brown gaiters, looking every inch of him the old soldier that he was.

"Well, Coates?" said I.

He cleared his throat.

"There are footprints in the radish-beds, sir," he reported.

"Footprints?"

"Yes, sir. Very deep. As though some one had jumped over the hedge and landed there."

"Jumped over the hedge!" I exclaimed. "That would be a considerable jump, Coates, from the road."

"It would, sir. Maybe she scrambled up."

"She?"

Coates cleared his throat again.

"There are three sets of prints in all. First a very deep one where the party had landed, then another broken up like, where she had turned round, and the third set with the heel-marks very deep where she had sprung back over the hedge."

"She?" I shouted.

"The prints, sir," resumed Coates, unmoved, "are those of a lady's high-heeled shoes."

I sat bolt upright in bed, staring at the man and scarcely able to credit my senses. Words failed me. Whereupon:

"Will you have tea or coffee for breakfast?" inquired Coates.

"Tea or coffee be damned, Coates!" I cried. "I'm going out to look at those footprints! If you had seen what I saw last night, even your old mahogany countenance would relax for once, I assure you."

"Indeed, sir," said Coates; "did you see the lady, then?"

"Lady!" I exclaimed, tumbling out of bed. "If the eyes that looked at me last night belonged to a 'lady' either I am mad or the 'lady' is of another world."

I pulled on a bath-robe and hurried out into the garden, Coates showing me the spot where he had found the mysterious foot-prints. A very brief examination sufficed to convince me that his account had been correct. Some one wearing high-heeled shoes clearly enough had stood there at some time whilst the soil was quite wet; and as no track led to or from the marks, Coates' conclusion that the person who had made them must have come over the hedge was the only feasible one. I turned to him in amazement, but recognizing in time the wildly fantastic nature of the sight which I had seen in the night, I refrained from speaking of the blazing eyes and made my way to the bathroom wondering if some chance reflection might not have deceived me and the presence of a woman's footmarks at the same spot be no more than a singular coincidence. Even so the mystery of their presence there remained unexplained.

My thoughts were diverted from a trend of profitless conjecture when shortly after breakfast time my 'phone bell rang. It was the editor of the Planet, to whom I had been indebted for a number of special commissions—including my fascinating quest of the Giant Gnu, which, generally supposed to be extinct, was reported by certain natives and others to survive in a remote corner of the Dark Continent.

Readers of the Planet will remember that although I failed to discover the Gnu I came upon a number of notable things on my journey through the almost unexplored country about the head-waters of the Niger.

"A most extraordinary case has cropped up," he said, "quite in your line, I think, Addison. Evidently a murder, and the circumstances seem to be most dramatic and unusual. I should be glad if you would take it up."

I inquired without much enthusiasm for details. Criminology was one of my hobbies, and in several instances I had traced cases of alleged haunting and other supposedly supernatural happenings to a criminal source; but the ordinary sordid murder did not interest me.

"The body of Sir Marcus Coverly has been found in a crate!" explained my friend. "The crate was being lowered into the hold of the S.S. Oritoga at the West India Docks. It had been delivered by a conveyance specially hired for the purpose apparently, as theOritoga is due to sail in an hour. There are all sorts of curious details but these you can learn for yourself. Don't trouble to call at the office; proceed straight to the dock."

"Right!" I said shortly. "I'll start immediately."

And this sudden decision had been brought about by the mention of the victim's name. Indeed, as I replaced the receiver on the hook I observed that my hand was shaking and I have little doubt that I had grown pale.

In the first place, then, let me confess that my retirement to the odd little retreat which at this time was my home, and my absorption in the obscure studies to which I have referred were not so much due to any natural liking for the life of a recluse as to the shattering of certain matrimonial designs. I had learned of the wreck of my hopes upon reading a press paragraph which announced the engagement of Isobel Merlin to Eric Coverly. And it was as much to conceal my disappointment from the world as for any better reason that I had slunk into retirement; for if I am slow to come to a decision in such a matter, once come to, it is of no light moment.

Yet although I had breathed no word of my lost dreams to Isobel but had congratulated her with the rest, often and bitterly I had cursed myself for a sluggard. Too late I had learned that she had but awaited a word from me; and I had gone off to Mesopotamia, leaving that word unspoken. During my absence Coverly had won the prize which I had thrown away. He was heir to the title, for his cousin, Sir Marcus, was unmarried. Now here, a bolt from the blue, came the news of his cousin's death!

It can well be imagined with what intense excitement I hurried to the docks. All other plans abandoned, Coates, arrayed in his neat blue uniform, ran the Rover round from the garage, and ere long we were jolting along the hideously uneven Commercial Road, East, dodging traction-engines drawing strings of lorries, and continually meeting delay in the form of those breakdowns which are of hourly occurrence in this congested but rugged highway.

In the West India Dock Road the way became slightly more open, but when at last I alighted and entered the dock gates I recognized that every newspaper and news agency in the kingdom was apparently represented. Jones, of the Gleaner, was coming out as I went in, and:

"Hello, Addison!" he cried, "this is quite in your line! It's as mad as 'Alice in Wonderland.'"

I did not delay, however, but hurried on in the direction of a dock building, at the door of which was gathered a heterogeneous group comprising newspaper men, dock officials, police and others who were unclassifiable. Half a dozen acquaintances greeted me as I came up, and I saw that the door was closed and that a constable stood on duty before it.

"I call it damned impudence, Addison!" exclaimed one pressman. "The dock people are refusing everybody information until Inspector Somebody-or-Other arrives from New Scotland Yard. I should think he has stopped on the way to get his lunch."

The speaker glanced impatiently at his watch and I went to speak to the man on duty.

"You have orders to admit no one, constable?" I asked.

"That's so, sir," he replied. "We're waiting for Detective-Inspector Gatton, who has been put in charge of the case."

"Ah! Gatton," I muttered, and, stepping aside from the expectant group, I filled and lighted my pipe, convinced that anything to be learned I should learn from Inspector Gatton, for he and I were old friends, having been mutually concerned in several interesting cases.

A few minutes later the Inspector arrived—a thick-set, clean-shaven, very bronzed man, his dark hair streaked with gray, and with all the appearance of a retired naval officer, in his well-cut blue serge suit and soft felt hat; a very reserved man whose innocent-looking blue eyes gave him that frank and open expression which is more often associated with a seaman than with a detective. He nodded to several acquaintances in the group, and then, observing me where I stood, came over and shook hands.

"Open the door, constable," he ordered quietly.

The constable produced a key and unlocked the door of the small stone building. Immediately there was a forward movement of the whole waiting group, but:

"If you please, gentlemen," said Gatton, raising his hand. "I must make my examination first; and Mr. Addison," he added, seeing the resentment written upon the faces of my disappointed confrères, "has special information which I am going to ask him to place at my disposal."

The constable stood aside and I followed Inspector Gatton into the stone shed.

"Lock the door again, constable," he ordered; "no one is to be admitted."

Thereupon I looked about me, and the scene which I beheld was so strange and gruesome that its every detail remains imprinted upon my memory.

The building then was lighted by four barred windows set so high in the walls that no one could look in from the outside. Blazing sunlight poured in at the two southerly windows and drew a sharp black pattern of the bars across the paved floor. Kneeling beside a stretcher, fully in this path of light, so that he presented a curious striped appearance, was a man who presently proved to be the divisional surgeon, and two paces beyond stood a police inspector who was engaged at the moment of our entrance in making entries in his note-book.

On the stretcher, so covered up that only his face was visible, lay one whom at first I failed to recognize, for the horribly contorted features presented a kind of mottled green appearance utterly indescribable.

Stifling an exclamation of horror, I stared and stared at that ghastly face, then:

"My God!" I muttered. "Yes! it is Sir Marcus!"

The surgeon stood up and the inspector advanced to meet Gatton, but my horrified gaze had strayed from the stretcher to a badly damaged and splintered packing-case, which was the only other object in the otherwise empty shed. At this I stared as much aghast as I had stared at the dead man.

The iron bands were broken and twisted and the whole of one side lay in fragments on the floor; but upon a board which had formed part of the top I perceived the figure of a cat roughly traced in green paint.

Beyond any shadow of doubt this crate was the same which on the night before had lain in the garage of the Red House!

Chapter

3

THE GREEN IMAGE

"YES," said Gatton, "I was speaking no more than the truth when I told them that you had special information which I hoped you would place at my disposal. Some of the particulars were given to me over the 'phone, you see, and I was glad to find you here when I arrived. I should have consulted you in any event, and principally about—that."

He pointed to an object which I held in my hand. It was a little green enamel image; the crouching figure of a woman having a cat's head, a piece of Egyptian workmanship probably of the fourth century B.C. Considered in conjunction with the figure painted upon the crate, the presence of this little image was so amazing a circumstance that from the moment when it had been placed in my hand I had stood staring at it almost dazedly.

The divisional surgeon had gone, and only the local officer remained with Gatton and myself in the building. Sir Marcus Coverly presented all the frightful appearance of one who has died by asphyxia, and although of course there would be an autopsy, little doubt existed respecting the mode of his death. The marks of violence found upon the body could be accounted for by the fact that the crate had fallen a distance of thirty feet into the hold, and the surgeon was convinced that the injuries to the body had all been received after death, death having taken place in his opinion fully twelve hours before.

"You see," said Gatton, "when the crate broke several things which presumably were in Sir Marcus' pockets were found lying loose amongst the wreckage. That cat-woman was one of them."

"Yet it may not have been in any of his pockets at all," said I.

"It may not," agreed Gatton. "But that it was somewhere in the crate is beyond dispute, I think. Besides this is more than a coincidence."

And he pointed to the painted cat upon the lid of the packing-case. I had already told him of the episode at the Red House on the previous night, and now:

"The fates are on our side," I said, "for at least we know where the crate was despatched from."

"Quite so," agreed Gatton. "We should have got that from the carter later, of course, but every minute saved in an affair such as this is worth considering. As a pressman you will probably disagree with me, but I propose to suppress these two pieces of evidence. Premature publication of clews too often handicaps us. Now, what is that figure exactly?"

"It is a votive offering of a kind used in Ancient Egypt by pilgrims to Bubastis. It is a genuine antique, and if you think the history of such relics is likely to assist the investigation I can give you some further particulars this evening if you have time to call at my place."

"I think," said Gatton, taking the figure from me and looking at it with a singular expression on his face, "that the history of the thing is very important. The fact that a rough reproduction of a somewhat similar figure is painted upon the case cannot possibly be a coincidence."

I stared at him silently for a moment, then:

"You mean that the crate was specially designed to contain the body?" I asked.

"I am certainly of that opinion," declared Inspector Heath, the local officer. "It is of just the right size and shape for the purpose."

Once more I began to examine the fragments stacked upon the floor, and then I looked again at the several objects which lay beside the crate. They were the personal belongings of the dead baronet and the police had carefully noted in which of his pockets each object had been found. He was in evening dress and a light top-coat had been packed into the crate beside him. In this had been found a cigar-case and a pair of gloves; a wallet containing £20 in Treasury notes and a number of cards and personal papers had fallen out of the crate together with the cat statuette. The face of his watch was broken. It had been in his waistcoat pocket but it still ticked steadily on where it lay there beside its dead owner. A gold-mounted malacca cane also figured amongst the relics of the gruesome crime; so that whatever had been the object of the murderer, that of robbery was out of the question.

"The next thing to do," said Gatton, "is to trace Sir Marcus's movements from the time that he left home last night to the time that he met his death. I am going out now to 'phone to the Yard. We ought to have succeeded in tracing the carter who brought the crate here before the evening. I personally shall proceed to Sir Marcus's rooms and then to this Red House around which it seems to me that the mystery centers."

He put the enamel figure into his pocket and taking up the broken board which bore the painted cat:

"You are carrying a top-coat," he said. "Hide this under it!"

He turned to Inspector Heath, nodding shortly.

"All right," he said, with a grim smile, "go out now and talk to the crowd!"

Having issued certain telephonic instructions touching the carter who had delivered the crate to the docks, and then imparting to the representatives of the press a guarded statement for publication, Inspector Gatton succeeded in wedging himself into my little two-seater and ere long we were lurching and bumping along the ill-paved East-end streets.

The late Sir Marcus's London address, which had been unknown to me, we had learned from his cards, and it was with the keenest anticipation of a notable discovery that I presently found myself with Gatton mounting the stairs to the chambers of the murdered baronet.

At the very moment of our arrival the door was opened and a man—quite obviously a constable in plain clothes—came out. Behind him I observed one whom I took to be the late Sir Marcus's servant, a pathetic and somewhat disheveled figure.

"Hello, Blythe!" said Gatton, "who instructed you to come here?"

"Sir Marcus's man—Morris—telephoned the Yard," was the reply, "as he couldn't understand what had become of his master and I was sent along to see him."

"Oh," said Gatton, "very good. Report to me in due course."

Blythe departed, and Gatton and I entered the hall. The man, Morris, closed the door, and led us into a small library. Beside the telephone stood a tray bearing decanter and glasses, and there was evidence that Morris had partaken of a hurried breakfast consisting only of biscuits and whisky and soda.

"I haven't been to bed all night, gentlemen," he began the moment that we entered the room. "Sir Marcus was a good master and if he was sleeping away from home he never failed to advise me, so that I knew even before the dreadful news reached me that something was amiss."

He was quite unstrung and his voice was unsteady. The reputation of the late baronet had been one which I personally did not envy him, but whatever his faults, and I knew they had been many, he had evidently possessed the redeeming virtue of being a good employer.

"A couple of hours' sleep would make a new man of you," said Gatton kindly. "I understand your feelings, but no amount of sorrow can mend matters, unfortunately. Now, I don't want to worry you, but there are one or two points which I must ask you to clear up. In the first place did you ever see this before?"

From his pocket he took out the little figure of Bâst, the cat-goddess, and held it up before Morris.

The man stared at it with lack-luster eyes, scratching his unshaven chin; then he shook his head slowly.

"Never," he declared. "No, I am positive I never saw a figure like that before."

"Then, secondly," continued Gatton, "was your master ever in Egypt?"

"Not that I am aware of; certainly not since I have been with him—six years on the thirty-first of this month."

"Ah," said Gatton. "Now, when did you last see Sir Marcus?"

"At half-past six last night, sir. He was dining at his club and then going to the New Avenue Theater. I booked a seat for him myself."

"He was going alone, then?"

"Yes."

Gatton glanced at me significantly and I experienced an uncomfortable thrill. In the inspector's glance I had read that he suspected the presence of a woman in the case and at the mention of the New Avenue Theater it had instantly occurred to me that Isobel Merlin was appearing there! Gatton turned again to Morris.

"Sir Marcus had not led you to suppose that there was any likelihood of his not returning last night?"

"No, sir; that was why, knowing his regular custom, I became so alarmed when he failed to come back or to 'phone."

Gatton stared hard at the speaker and:

"It will be no breach of confidence on your part," he said, speaking slowly and deliberately, "for you to answer my next question. The best service you can do your late master now will be to help us to apprehend his murderer."

He paused a moment, then:

"Was Sir Marcus interested in some one engaged at the New Avenue Theater?" he asked.

Morris glanced from face to face in a pathetic, troubled fashion. He rubbed the stubble on his chin again and hesitated. Finally:

"I believe," he replied, "that there was a lady there who—"

He paused, swallowing, and:

"Yes," Gatton prompted, "who—?"

"Who—interested Sir Marcus; but I don't know her name nor anything about her," he declared. "I knew about—some of the others, but Sir Marcus was—very reserved about this lady, which made me think—"

"Yes?"

"That he perhaps hadn't been so successful."

Morris ceased speaking and sat staring at a bookcase vacantly.

"Ah," murmured Gatton. Then, abruptly: "Did Sir Marcus ever visit any one who lived in College Road?" he demanded.

Morris looked up wearily.

"College Road?" he repeated. "Where is that, sir?"

"It doesn't matter," said Gatton shortly, "if the name is unfamiliar to you. Had Sir Marcus a car?"

"Not latterly, sir."

"Any other servants?"

"No. As a bachelor he had no use for a large establishment, and Friars' Park remains in the possession of the late Sir Burnham's widow."

"Sir Burnham? Sir Marcus's uncle?"

"Yes."

"What living relatives had Sir Marcus?"

"His aunt—Lady Burnham Coverly—with whom I believe he was on bad terms. Her own son, who ought to have inherited the title, was dead, you see. I think she felt bitterly towards my master. The only other relative I ever heard of was Mr. Eric—Sir Marcus's second cousin—now Sir Eric, of course."

I turned aside, glancing at some books which lay scattered on the table. The wound was a new one and I suppose I was not man enough to hide the pain which mention of Eric Coverly still occasioned me.

"Were the cousins good friends?" continued the even, remorseless voice of the inquisitor.

Morris looked up quickly.

"They were not, sir," he answered. "They never had been. But some few months back a fresh quarrel arose and one night in this very room it almost came to blows."

"Indeed? What was the quarrel about?"

The old hesitancy claimed Morris again, but at last:

"Of course," he said, with visible embarrassment, "it was—a woman."

I felt my heart leaping wildly, but I managed to preserve an outward show of composure.

"What woman?" demanded Gatton.

"I don't know, sir."

"Do you mean it?"

A fierce note of challenge had come into the quiet voice, but Morris looked up and met Gatton's searching stare unflinchingly.

"I swear it," he said. "I never was an eavesdropper."

"I suggest it was the same woman that Sir Marcus went to see last night?" Gatton continued.

The examination of Morris had reached a point at which I found myself hard put to it to retain even a seeming of composure. All Gatton's questions had been leading up to this suggestion, as I now perceived clearly enough; and from the cousins' quarrel to Isobel, Eric's fiancée, who was engaged at the New Avenue Theater, was an inevitable step. But:

"Possibly, sir," was Morris's only answer.

Inspector Gatton stared hard at the man for a moment or so, then:

"Very well," he said. "Take my advice and turn in. There will be much for you to do presently, I am afraid. Who was Sir Marcus's solicitor?"

Morris gave the desired information in a tired, toneless voice, and we departed. Little did Gatton realize that his words were barbed, when, as we descended to the street, he said:

"I have a call to make at Scotland Yard next, after which my first visit will be to the stage-doorkeeper of the New Avenue Theater."

"Can I be of further assistance to you at the moment?" I asked, endeavoring to speak casually.

"Thanks, no. But I should welcome your company this afternoon at my examination of the Red House. I understand that it is in your neighborhood, so perhaps as you are also professionally interested in the case, you might arrange to meet me there. Are you returning home now or going to the Planet office?"

"I think to the office," I replied. "In any event 'phone there making an appointment and I will meet you at the Red House."

Chapter

4

ISOBEL

Ten minutes later I was standing in a charming little boudoir which too often figured in my daydreams. My own photograph was upon the mantelpiece, and in Isobel's dark eyes when she greeted me there was a light which I lacked the courage to try to understand. I had not at that time learned what I learned later, and have already indicated, that my own foolish silence had wounded Isobel as deeply as her subsequent engagement to Eric Coverly had wounded me.

The psychology of a woman is intriguing in its very naïveté, and now as she stood before me, slim and graceful in her well-cut walking costume, a quick flicker of red flaming in her cheeks and her eyes alight with that sweet tantalizing look in which expectation and a hot pride were mingled, I wondered and felt sick at heart. Desirable she was beyond any other woman I had known, and I called myself witling coward, to have avoided putting my fortune to the test on that fatal day of my departure for Mesopotamia. For just as she looked at me now she had looked at me then. But to-day she was evidently on the point of setting out—I did not doubt with the purpose of meeting Eric Coverly; on that day of the irrevocable past she had been free and I had been silent.

"You nearly missed me, Jack," she said gayly. "I was just going out."

By the very good-fellowship of her greeting she restored me to myself and enabled me to stamp down—at least temporarily—the monster through whose greedy eyes I had found myself considering the happiness of Eric Coverly.