Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

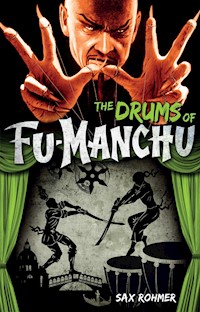

"Imagine a person, tall, lean, and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan..." FU-MANCHU EUROPE, 1939—the year before World War II and global chaos. A time of shadows, secret societies, and international conflict. Into this world on the brink comes the most fantastic emissary of evil society has ever known... In order to control the Si-Fan, and then the world, Fu-Manchu must assassinate the dictators who have brought Europe to the brink of war. This places Sir Denis Nayland Smith in the impossible position of defending warmongers who may be as evil as the Devil Doctor himself! ALSO IN THIS VOLUME: A LONG-LOST NAYLAND SMITH SHORT STORY! "Fu Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant."—Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships AFTERWORD BY LESLIE S. KLINGER (THE ANNOTATED SANDMAN by Neil Gaiman)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise

Also by Sax Rohmer

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One: Mystery Comes to Bayswater

Chapter Two: Sir Malcolm’s Guest

Chapter Three: The Green Death

Chapter Four: The Girl Outside

Chapter Five: Three Notices

Chapter Six: Satan Incarnate

Chapter Seven: “Inspector Gallaho Reports”

Chapter Eight: In the Essex Marshes

Chapter Nine: The Hut by the Creek

Chapter Ten: The Mandarin’s Cap

Chapter Eleven: At the Monks’ Arms

Chapter Twelve: Dr. Fu-Manchu’s Bodyguard

Chapter Thirteen: In the Wine Cellars

Chapter Fourteen: The Monks’ Arms (Concluded)

Chapter Fifteen: The Si-Fan

Chapter Sixteen: Great Oaks

Chapter Seventeen: In the Laboratory

Chapter Eighteen: Dr. Martin Jasper

Chapter Nineteen: Constable Isles’s Statement

Chapter Twenty: A Modern Vampire

Chapter Twenty-One: The Red Button

Chapter Twenty-Two: Living Death

Chapter Twenty-Three: Tremors Under Europe

Chapter Twenty-Four: A Car in Hyde Park

Chapter Twenty-Five: “The Brain is Dr. Fu-Manchu”

Chapter Twenty-Six: Venice

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Ardatha

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Nayland Smith’s Room

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Venice Claims a Victim

Chapter Thirty: A Woman Drops a Rose

Chapter Thirty-One: Palazzo Mori

Chapter Thirty-Two: The Zombie

Chapter Thirty-Three: Ancient Tortures

Chapter Thirty-Four: The Tongs

Chapter Thirty-Five: Korêani

Chapter Thirty-Six: Behind the Arras

Chapter Thirty-Seven: The Lotus Floor

Chapter Thirty-Eight: In the Palazzo Brioni

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Silver Heels

Chapter Forty: Silver Heels (Continued)

Chapter Forty-One: Silver Heels (Concluded)

Chapter Forty-Two: The Man in the Park

Chapter Forty-Three: My Doorbell Rings

Chapter Forty-Four: “Always I am Just”

Chapter Forty-Five: The Mushrabîyeh Screen

Chapter Forty-Six: Pursuing a Shadow

Chapter Forty-Seven: What Happened in Downing Street

Chapter Forty-Eight: “First Notice”

Chapter Forty-Nine: Blue Carnations

Chapter Fifty: Ardatha’s Message

Chapter Fifty-One: The Thing with Red Eyes

Chapter Fifty-Two: The Thing with Red Eyes (Concluded)

Introduction to “The Mark of the Monkey”

The Mark of the Monkey

About the Author

Appreciating Dr. Fu-Manchu

Also Available from Titan Books

“Without Fu-Manchu we wouldn’t have Dr. No, Doctor Doom or Dr. Evil. Sax Rohmer created the first truly great evil mastermind. Devious, inventive, complex, and fascinating. These novels inspired a century of great thrillers!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Assassin’s Code and Patient Zero

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.”

James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th Century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction… at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.”

Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson… though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.”

Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in… For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”

K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro—or more precisely with Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Darth Vader, and Lex Luthor—in the imaginations of generations of readers and moviegoers.”

Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIES BY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE RETURN OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER: FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686114

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686770

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First published as a novel in the UK by Cassell and Co. Ltd, 1939

First published in the US by Doubleday, Doran, 1939

First Titan Books edition: June 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2014 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

Frontispiece photograph by William Ritter, from Collier’s Weekly, April 1, 1939. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu,” http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

“Long, narrow eyes seemed to be watching me. They held my gaze hypnotically.”.

CHAPTER ONE

MYSTERY COMES TO BAYSWATER

“Damn it! There is someone there!”

I sprang up irritably, jerked the curtains aside and stared down into Bayswater Road. My bell, “Bart Kerrigan” inscribed above it on a plate outside in the street, was sometimes rung wantonly, by late revellers. The bell was out of order and I had tried to ignore its faint tinkling. But now, staring down, I saw someone looking up at me as I stood in the lighted room: a man wearing a Burberry and a soft hat, a man who signalled urgently with his arms, indicating: “Come down!”

Shooting the bolt open so that I should not be locked out, I ran downstairs. A light in the glazed arcade which led to the front door refused to function. Groping my way I threw the door open.

The man in the Burberry almost upset me as he leapt in.

“Who the devil are you?”

The door was closed quietly and the intruder spoke, his back to it as he faced me.

“It’s not a holdup,” came in coldly incisive tones. “I just had to get in. Thanks, Kerrigan, but you were a long time coming down.”

“Good heavens!” I stepped forward in the darkness and extended my hand. “Nayland Smith! Can I believe it?”

“Absolutely! I was desperate. Is your bell out of order?”

“Yes.”

“I thought so. Don’t turn the light up.”

“I can’t; the fuse is blown.”

“Good. I gather that I interrupted you, but I had an excellent reason. Come on.”

As we hurried up the semi-dark staircase, I found my brain in some confusion. And when we entered my flat:

“Leave your dining room in darkness,” snapped Nayland Smith. “I want to look out of the window.”

Breathless, between astonishment and the race up the stairs, I stood behind him as he stared out of the dining-room window. Two men were loitering near the front door—and glancing up toward my lighted study.

“Only just in time!” said Nayland Smith. “I tricked them—but you see how wonderfully they are informed. Evidently they know every possible spot in which I might take cover. Unpleasantly near thing, Kerrigan.”

In the lighted study I gazed at my visitor. Hat removed, Nayland Smith revealed a head of virile curling hair, more grey than black. Stripping off his Burberry, he faced me. His clean-cut features, burned by a recent visit to the tropics, looked almost haggardly thin, but the fire in his eyes, the tense nervous vitality of the man must have struck a spark of animosity or of friendship in any but a soul dead.

He stared at me analytically.

“You look well, Kerrigan. You have passed twenty-seven, but you are lean as a hare, clean-cut and obviously fit as a flea. The last time I saw you was in Addis-Ababa. You were sending articles to the Orbit and I was sending reports to the Foreign Office. Well, what is it now?”

He stared down at the littered writing desk. I moved towards the dining room.

“Drinks? Good!” he snapped. “But you must find them in the dark.”

“I understand.”

When presently I returned with a decanter and syphon:

“Look here,” I said, “I was never happier to see a man in my life. But bring me up to date: what’s the meaning of all this?”

Nayland Smith dropped a page which he had been reading and began reflectively to stuff coarse-cut mixture into his briar.

“You are writing a book about Abyssinia, I see.”

“Yes.”

“You are not on the staff of the Orbit, are you?”

“No. I am in the fortunate position of picking and choosing my jobs. I did the series on Abyssinia for them because I know that part of Africa pretty well. Now, I am doing a book on present conditions.”

As I poured out drinks:

“Excuse me,” said Nayland Smith, “I just want to make sure.”

He walked into the darkened dining room, carefully closing the door behind him. When he returned:

“May I use your phone?”

“Certainly.”

I handed him a drink of which he took a sip, then, raising the telephone receiver, he dialled a number rapidly, and:

“Yes!” His speech was curiously staccato. “Put me through to Chief Inspector Wessex’ office. Sir Denis Nayland Smith speaking. Hurry!”

There was an interval. I watched my visitor fascinatedly. In my considerable experience of men, I had never known one who lived at such high pressure.

“Is that Inspector Wessex?… Good. I have a job for you, Inspector. Instruct Paddington Police Station to send a party in a fast car. They will find two men—dark-skinned foreigners—hanging about near the corner of Porchester Terrace. They are to arrest them—never mind the charge—and lock them up. I will deal with them later. Can I leave this to you?”

Presumably the invisible chief inspector agreed to take charge of the matter, for Nayland Smith hung up the receiver.

“I have brought you your biggest story, Kerrigan. I know you can afford to await my word before publishing. I may add”—tapping the loose manuscript on the desk—“that you have missed the real truth about Abyssinia, but I can rectify that.” He began in his restless way to pace up and down the carpet. “Without mentioning any names, a prominent cabinet minister resigned quite recently. Do you recall it?”

“Certainly.”

“He was a wise man. Do you know why he retired?”

“There are several versions of the story.”

“He has a fine brain—and he retired because he recognised that there was in the world one first-class brain. He retired to review his ideas on the immediate destiny of civilisation.”

“What do you mean?”

“The thing most desired, Kerrigan, by all women, by all sensible men, in this life, is peace. Wars are made by few but fought by many. The greatest intellect in the world today has decided that there must be peace! It has become my business to try to save the lives of certain prominent persons who are blind enough to believe that they can make war. I was en route for Sir Malcolm Locke’s house, which is not five minutes’ drive away, when I realised that a small Daimler was following me. I remembered, fortunately, that your flat was here, and trusted to luck that you would be at home. I worked an old trick. Fey, my man, slowed up around a corner just before the following car had turned it. I stepped out and cut through a mews. Fey drove on. But my two followers evidently detected the trick. I saw them coming back just before you opened the door! They know I am in one of two buildings. What I don’t want them to know is where I am going. Hello—!”

The sound of a speeding automobile suddenly braked came up from Bayswater Road.

“Into the dining room!”

I dashed in behind Nayland Smith. We stared down. A police car stood outside. There were few pedestrians and there was comparatively little traffic. It was the lull before eleven o’clock, the lull which precedes the storm of returning theatre and picture goers. A queer scene was being enacted on the pavement almost directly below my windows.

Two men (except that they were dark fellows I could discern no more from my viewpoint) were struggling and protesting volubly amid a group of uniformed constables. Beyond, on the park side, I saw now a small car standing—it looked like a Daimler. A constable on patrol joined the party, and the police driver pointed in the direction of the Daimler. The expostulating prisoners were hustled in, the police car was driven off and the constable in the determined but leisurely way of his kind paced stolidly across the road.

“All clear!” said Nayland Smith. “Come along! I want you with me!”

“But, Sir Malcolm Locke? In what way can he be?”

“He’s the cousin of the home secretary. As a matter of fact, he’s abroad. It isn’t Locke I want to see, but a guest who is staying at his house. I must get to him, Kerrigan, without a moment’s delay!”

“A guest?”

“Say, rather, someone who is hiding there.”

“Hiding?”

“I can’t mention his name—yet. But he returned secretly from Africa. He is the driving power behind one of Europe’s dictators. By consent of the British Foreign Office, he came, also secretly, to London. Can you imagine why?”

“No.”

“To see me!”

CHAPTER TWO

SIR MALCOLM’S GUEST

Fey, that expressionless, leather-faced valet-chauffeur of Nayland Smith’s, was standing at the door beside the Rolls, rug over arm, as though nothing unusual had occurred; and as we proceeded towards Sir Malcolm’s house, Smith, smoking furiously, fell into a silence which I did not care to interrupt.

I count myself psychic, for this is a Celtic heritage, yet on this short journey nothing told me that, although as correspondent for the Orbit I had had a not uneventful life, I was about to become mixed up in a drama the outcome of which meant nothing less than the destruction of what we are pleased to call Civilisation. And in averting Armageddon, by the oddest paradox I was to find myself opposed to the one man who, alone, could save Europe from destruction.

Sir Malcolm Locke’s house presented an unexpectedly festive appearance as we approached. Nearly every window in the large building was illuminated; a number of cars were drawn up and a considerable group of people had congregated outside the front door.

“Hello!” muttered Nayland Smith. He knocked out his pipe in the ash tray and dropped the briar into a pocket of his Burberry. “This is very odd.”

Before Fey had pulled in Smith was out and dashing up the steps. I followed and reached him just as the door was opened by a butler. The man’s face wore a horrified expression: a constable was hurrying up behind us.

“Sir Malcolm is not at home, sir.”

“I am not here to see Sir Malcolm, but his guest. My name is Nayland Smith. My business is official.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” said the butler, with a swift change, of manner. “I didn’t recognise you.”

The door opened straight into a lofty hallway, from the further end of which a crescent staircase led to upper floors. As the butler closed the door I immediately became conscious of a curiously vibrant atmosphere. I had experienced it before, in places taken by assault or bombed. It is caused, I think, by the vibrations of frightened minds. Several servants were peering down from a dark landing above but the hallway itself was brightly lighted. At this moment, a door on the right opened and a clean-shaven, heavily built man with jet-black, close-cropped hair came out. He glanced in our direction.

“Good evening, Inspector,” said Nayland Smith. “What’s this? What are you doing here?”

“Thank God you’ve arrived, sir!” The inspector stopped dead in his stride. “I was beginning to fear something was wrong.”

“This is Mr Bart Kerrigan—Chief Inspector Leighton of the Special Branch.”

Nayland Smith’s loud, rather harsh tones evidently having penetrated to the room beyond, again the door opened, and I saw with astonishment Sir James Clare, the home secretary, come out.

“Here at last, Smith,” was his greeting. “I heard your voice.” Sir James spoke in a clear but nearly toneless manner which betrayed his legal training. “I don’t know your friend”—staring at me through the thick pebbles of his spectacles. “This unhappy business, of course, is tremendously confidential.”

Nayland Smith made a rapid introduction.

“Mr Kerrigan is acting for no newspaper or agency. You may take his discretion for granted. You say this unhappy business, Sir James? May I ask—”

Sir James Clare raised his hand to check the speaker. He turned to Inspector Leighton.

“See if there is any news about the telephone call, Inspector,” he directed, and as the inspector hurried away: “Suppose, gentlemen, you come in here for a moment.”

We followed him back into the apartment from which he had come. It was a large library, a lofty room, every available foot of the wall occupied by bookcases. Beside a mahogany table upon which, also, were many books and a number of documents, he sat down in an armchair, indicating that we should sit in two others. Smith was far too restless for inaction, but grunting irritably he threw himself down into one of the padded chairs.

“Chief Inspector Leighton of the Special Branch,” said Sir James, “is naturally acquainted with the identity of Sir Malcolm’s guest. But no one else in the house has been informed, with the exception of Mr Bascombe, Sir Malcolm’s private secretary. In the circumstances I think perhaps we had better talk in here. Am I to take it that you are unaware of what occurred tonight?”

“On your instructions,” said Smith, speaking with a sort of smothered irritability, “I flew from Berlin this evening. I was on my way here, and I can only suppose that the purpose of my return was known. A deliberate attempt was made tonight to wreck my car as I crossed Bond Street, by the driver of a lorry. Only Fey’s skill and the fact that at so late an hour there were no pedestrians averted disaster. He drove right on to the pavement and along it for some little distance.”

“Did you apprehend the driver of this lorry?”

“I did not stop to do so, although I recognised the fact that it was a planned attack. Then, when we reached Marble Arch, I realised that two men were following in a Daimler. I managed to throw them off the track, with Mr Kerrigan’s assistance—and here I am. What has happened?”

“General Quinto is dead!”

CHAPTER THREE

THE GREEN DEATH

This news, coupled with the identity of the hidden guest, shocked me inexpressibly. General Quinto! Chief of Staff to Signor Monaghani; one of the most formidable figures in political Europe! The man who would command Monaghani’s forces in the event of war; the first soldier in his country, almost certain successor to the dictator! But if I was shocked, the effect upon Nayland Smith was electrical.

He sprang lip with clenched fists and glared at Sir James Clare.

“Good God, Sir James! You are not telling me that he has been—”

The home secretary shook his head. His legal calm remained unruffled.

“That question, Smith, I am not yet in a position to answer. But you know now why I am here; why Inspector Leighton is here.” He stood up. “I shall, be glad, gentlemen, if you will follow me to the study which had been placed at the disposal of the general, and in which he died.”

A door at the further end of the library was thrown open and I entered a small study, intimately furnished. There was a writing desk near a curtained window, which showed evidence of someone’s recent activities. But my attention was immediately focussed upon a settee in an arched recess upon which lay the body of a man. One glance was sufficient—for I had seen him many times in Africa.

It was General Quinto. But his normally sallow aquiline features displayed an agonised surprise and had acquired a sort of ghastly greenish hue. I cannot better describe what I mean than by likening the effect to that produced by green limelight.

A man whose features I could not distinguish was kneeling beside the body, which he appeared to be closely examining. A second man looked down at him; and as we entered the first stood up and turned.

It was Lord Moreton, the king’s physician.

Introductions revealed that the other was Dr. Sims, the divisional police surgeon.

“This is a very strange business,” said the famous consultant, removing his spectacles and placing them in a pocket of his dress waistcoat. “Do you know”—he looked from face to face, with a sort of naive astonishment—“I have no idea what killed this man!”

“This is really terrible,” declared Sir James Clare. “Personal considerations apart, his death here in London under such circumstances cannot fail to set ugly rumours afloat. I take it that you mean, Lord Moreton, that you are not prepared to give a certificate of death from natural causes?”

“Honestly,” the physician replied, staring intently at him, “I am not. I am by no means satisfied that he did die from natural causes.”

“I am perfectly sure that he didn’t,” the police surgeon declared.

Nayland Smith, who had been staring down at the body of the dead soldier, now began sniffing the air suspiciously.

“I observe, Sir Denis,” said Lord Moreton, “that you have detected a faint but peculiar odour in the atmosphere?”

“I have. Had you noticed it?”

“At the very moment that I entered the room. I cannot identify it; it is something outside my experience. It grows less perceptible—or I am becoming used to it.”

I, too, had detected this strange but not unpleasant odour. Now, apparently guided by his sense of smell, Nayland Smith began to approach the writing desk. Here he paused, sniffing vigorously. At this moment the door opened and Inspector Leighton came in.

“I see you are trying to trace the smell, sir. I thought it was stronger by the writing desk than elsewhere, but I could find nothing to account for it.”

“You have searched thoroughly?” Smith snapped.

“Absolutely, sir. I think I may say I have searched every inch of the room.”

Nayland Smith stood by the desk tugging at the lobe of his ear, a mannerism which indicated perplexity, as I knew; then:

“Do these gentlemen know the identity of the victim?” he asked the minister.

“Yes.”

“In that case, who actually saw General Quinto last alive?”

“Mr Bascombe, Sir Malcolm’s private secretary.”

“Very well. I have reasons for wishing that Mr Kerrigan should be in a position to confirm anything that I may discover in this matter. Where was the body found?”

“Where it lies now.”

“By whom?”

“By Mr Bascombe. He phoned the news to me.”

Smith glanced at Inspector Leighton.

“The body has been disturbed in no way, Inspector?”

“In no way.”

“In that case I should like a private interview with Mr Bascombe. I wish Mr Kerrigan to remain. Perhaps, Lord Moreton and Doctor Sims, you would be good enough to wait in the library with Sir James and the Inspector…”

* * *

Mr Bascombe was a tall fair man, approaching middle age. He carried himself with a slight stoop, although I learned that he was a Cambridge rowing Blue. His manner was gentle to the point of diffidence. As he entered the study he glanced in a horrified way at the body on the settee.

“Good evening, Mr Bascombe,” said Nayland Smith, who was standing before the writing table, “I thought it better that I should see you privately. I gather from Inspector Leighton that General Quinto, who arrived here yesterday morning at eleven o’clock, was to all intents and purposes hiding in these rooms.”

“That is so, Sir Denis. The door behind you, there, opens into a bedroom, and a bathroom adjoins it. Sir Malcolm, who is a very late worker, sometimes slept there in order to avoid disturbing Lady Locke.”

“And since his arrival, the general has never left those apartments?”

“No.”

“He was a very old friend of Sir Malcolm’s?”

“Yes, a lifelong friend, I understand. He and Lady Locke are in the south of France, but are expected back tomorrow morning.”

“No member of the staff is aware of the identity of the visitor?”

“No. He had never stayed here during the time of Greaves, the butler—that is, during the last three years—and he was a stranger to all the other servants.”

“By what name was he known here?”

“Mr Victor.”

“Who looked after him?”

“Greaves.”

“No one else?”

“No one, except myself and Greaves, entered these rooms.”

“The general expected me tonight, of course?”

“Yes. He was very excited when you did not appear.”

“How has he occupied himself since his arrival?”

“Writing almost continuously, when he was not pacing up and down the library, or glancing out of the windows into the square.”

“What was he writing?”

“I don’t know. He tore up every shred of it. Late this evening he had a fire lighted in the library and burnt up everything.”

“Extraordinary! Did he seem very apprehensive?”

“Very. Had I not known his reputation, I should have said, in fact, that he was panic-stricken. This frame of mind seemed to date from his receipt of a letter delivered by a district messenger at noon yesterday.”

“Where is this letter?”

“I have reason to believe that the general locked it in a dispatch box which he brought with him.”

“Did he comment upon the letter?”

“No.”

“In what name was it addressed?”

“Mr Victor.”

Nayland Smith began to pace the carpet, and every time he passed the settee where that grim body lay, the right arm hanging down so that half-closed fingers touched the floor, his shadow, moving across the ghastly, greenish face, created an impression that the features worked and twitched and became still again.

“Did he make many telephone calls?”

“Quite a number.”

“From the instrument on the desk there?”

“Yes—it is an extension from the hallway.”

“Have you a record of those whom he called?”

“Of some. Inspector Leighton has already made that inquiry. There were two long conversations with Rome, several calls to Sir James Clare and some talks with his own embassy.”

“But others you have been unable to check?”

“The inspector is at work on that now, I understand, Sir Denis. There was—er—a lady.”

“Indeed? Any incoming calls?”

“Very few.”

“I remember—the inspector told me he was trying to trace them. Any visitors?”

“Sir James Clare yesterday morning, Count Bruzzi at noon today—and, oh yes, a lady last, night.”

“What! A lady?”

“Yes.”

“What was her name?”

“I have no idea, Sir Denis. She came just after dusk in a car which waited outside, and sent a sealed note in by Greaves. I may say that at the request of the general I was almost continuously at work in the library, so that no one could gain access without my permission. This note was handed to me.”

“Was anything written on the envelope?”

“Yes: ‘Personal—for Mr Victor.’ I took it to him. He was then seated at the desk writing. He seemed delighted. He evidently recognised the handwriting. Having read the message, he instructed me to admit the visitor.”

“Describe her,” said Nayland Smith.

“Tall and slender, with fine eyes, very long and narrow—definitely not an Englishwoman. She had graceful and languid manners, and remarkable composure. Her hair was jet black and closely waved to her head. She wore jade earrings and was wrapped up in what I assumed to be a very expensive fur coat.”

“H’m!” murmured Nayland Smith, “can’t place her, unless”—and a startled expression momentarily crossed his brown features—“the dead are living again!”

“She remained in the study with the general for close upon an hour. Their voices sounded animated, but of course I actually overheard nothing of their words. Then the door was opened and they both came out. I rang for Greaves, the general conducted his visitor as far as the end of the library and Greaves saw her down to her car.”

“What occurred then? Did the general, seem to be disturbed in any way? Unusually happy or unusually sad?”

“He was smiling when he returned to the study, which he did immediately, going in and closing the door.”

“And today, Count Bruzzi?”

“Count Bruzzi lunched with him. There have been no other visitors.”

“Phone calls?”

“One at half past seven. It was immediately after this that General Quinto came out and told me that you were expected, Sir Denis, between ten and eleven, and were to be shown immediately into the study.”

“Yes. I was recalled from Berlin for this interview which now cannot take place. This brings us, Mr Bascombe, to the ghastly business of tonight.”

“The general and I dined alone in the library, Greaves waiting.”

“Did you both eat the same dishes and drink the same wine?”

“We did. Your suspicions are natural, Sir Denis, but such a solution of the mystery is impossible. It was a plain and typically English dinner—a shoulder of lamb with mint sauce, peas and new potatoes. Greaves carved and served. Followed by apple tart and cream of which we both partook, then cheese and young radishes. We shared a bottle of claret. That was our simple meal.”

Nayland Smith had begun to walk up and down again. Mr Bascombe continued:

“I went out for an hour after dinner. During my absence General Quinto received a telephone call and afterwards complained to Greaves that there was something wrong with the extension to the study—that he had found difficulty in making himself audible. Greaves informed him that the post office was aware of this defect and that an engineer was actually coming along at the moment to endeavour to rectify it. As a matter of fact the man was here when I returned.”

“Where was the general?”

“Reading in the library, outside. The man assured me that the instrument was now in order, made a test call and General Quinto returned to the study and closed the door. I remained in the library.”

“What time was this?”

“As nearly as I can remember, a quarter to ten.”

“Yes, go on.”

“I sat at the library table writing personal letters, when I heard Greaves in the hall outside putting a call through to the general in the study. I heard General Quinto answer it, dimly at first, then more clearly. He seemed to be shouting into the receiver. Presently he came out in a state of some excitement—he was, I may add, a very irascible man. He said: ‘That fool has made the instrument worse. The lady to whom I was speaking could not hear a word.’ ”

“Realising that it was too late to expect the post office to send anyone again tonight, I went into the study and tested the instrument myself.”

“But,” snapped Nayland Smith, “did you observe anything unusual in the atmosphere of the room?”

“Yes—a curious odour, which still lingers here as a matter of fact.”

“Good! Go on.”

“I put a call through to a friend in Chelsea and was unable to detect anything the matter with the line.”

“It was perfectly clear?”

“Perfectly. I suggested to the general that possibly the fault was with his friend’s instrument and not with ours. I then returned to the library. He was in an extraordinarily excited condition—kept glancing at his watch and inquiring why you had not arrived. Some ten minutes later he threw the door open and came out again. He said: ‘Listen!’

“I stood up and we both remained quite silent for a moment. ‘Did you hear it?’ he asked.

“‘Hear what, General?” I replied.

“ ‘Someone beating a drum!’ ”

“Stop!” snapped Smith. “Those were his exact words?”

“His exact, words… ‘Surely you can hear it?’ he said. ‘An Arab drum—what they call a darabukkeh. Listen again.’

“I listened, but on my word of honour could hear nothing whatever. I assured the general of this. His face was inflamed and he remained very excited. He went in and slammed the door—but I had scarcely seated myself before he was out again.

“ ‘Mr Bascombe,’ he shouted (as you probably know he spoke perfect English), ‘someone is trying to frighten me! But by heavens they won’t! Come into the study: Perhaps you will hear it there!’ ”

“I went into the study with him, now seriously concerned. He grasped my arm—his hand was trembling. ‘Listen!’ he said, ‘it’s coming nearer—the beating of a drum—’

“Again I listened for some time. Finally: ‘I’m sorry, General,’ I had to say, ‘but I can hear nothing whatever beyond the usual sounds of distant traffic.’

“The incident had greatly disturbed me. I didn’t like the look of the general. This talk of drums was unpleasant and uncanny: He asked again what on earth had happened to you, Sir Denis, but declined my suggestion of a game of cards, so that again I left him and returned to the library. I heard him walking about for a time and then his footsteps ceased: Once I heard him cry out: ‘Stop those drums!’ Then I heard no more.”

“Had he referred to the curious odour?”

“He said: ‘Someone wearing a filthy perfume has been in this room.’ At about twenty to eleven, as he had become quite silent, I rapped on the door, opened it and went in. He turned shudderingly in the direction of the settee: “I found him as you see him.”

“Was he dead?”

“So far as I was able to judge, he was.”

CHAPTER FOUR

THE GIRL OUTSIDE

To that expression of agonised surprise upon the dead man’s face was now added, almost momentarily, a deepening of the greenish tinge. A fingerprint expert and a photographer from Scotland Yard had come and gone. After a longish interview, Nayland Smith had released Lord Moreton and Dr. Sims. He put a call through on the desk telephone which General Quinto had found defective. Smith found it in perfect order. He examined the adjoining bedroom and the bathroom beyond and pointed out that it was just possible, although there was no evidence to confirm the theory, that someone might have entered through the bathroom window during the time that the general was alone in the study.

“I don’t think that’s how it was done,” he said, “but it is a possibility. This dispatch box must be opened, and if Mr Bascombe can’t find the key we must force it. In the meantime, Kerrigan, you have a nose for news. I have observed that quite a number of people remain outside the house. Slip out the back way, go around and join the crowd. Ask stupid questions and study every one of them. It would not surprise me to learn that there is someone there waiting to hear of the success or failure of tonight’s plot.”

“Then you are satisfied that General Quinto was—murdered?”

“Entirely satisfied, Kerrigan.”

When presently I came out into the square I found that Lord Moreton’s car had gone. Smith’s, that of the home secretary and a Yard car were still standing there. Ten or twelve people were hanging about, attracted by that almost psychic awareness of tragedy which ahead of radio or newspaper in some mysterious way creeps through.

I examined them all carefully and selected several for conversation. Apart from the fact that they had heard that “something had happened,” I gathered little news of value.

Then standing apart from the main group, I saw a girl.

This was a dark night but suddenly the house door was opened to admit someone who had driven up in a taxi. In the light from the doorway, I had a glimpse of her face. She was dressed like a working girl, wearing a light raincoat which, however, did not disguise the lines of her slim, trim figure. She wore a brown beret. But her face, as the light shone fully upon it, was so really lovely—a word which rarely can be applied—that I was astonished. In the shadows she looked like a brunette; in the swift light I saw red glints in her tightly waved hair beneath the beret, exquisitely modelled features, lips parted in what I can only describe as an expectant smile. She turned and stared at the departing taxi as I strolled in her direction.

“Any idea what’s going on here?” I asked casually.

She raised her eyes in a startled way (they were wonderful eyes of a most unusual colour; they set me thinking of amethysts) keeping her hands tucked in the pockets of her coat.

“Someone told me”—she spoke broken English—“that something terrible had happened in this house.”

“Really! I couldn’t make out what the crowd was about. So that’s it! Who’s the owner of the house? Do you know?”

“Someone told me Sir Malcolm Locke.”

“Oh yes—he writes books, doesn’t he?”

“I don’t know. They told me Sir Malcolm Locke.”

She glanced up again and smiled. She had a most adorable, provocative smile. I could not place her, but I thought that with that face and figure she might be a mannequin or perhaps a show girl in a cabaret.

“Do you know Sir Malcolm Locke?” she asked, suddenly growing serious.

“No”—her change of manner had quite startled me—“except by name.”

“May I speak truly to you? You look”—she hesitated—“sensible.” There was a caressing note in her voice. “I know someone, who is in that house. Do you understand?”

Nayland Smith had made the right move. Here was a spy of the enemy. Whatever my personal predilection, this charming young lady should be in the hands of Detective Inspector Leighton without delay.

“That’s very interesting. Who is it?”

“Just someone I know. You see”—she laid her hand on my arm, and inclined ever so slightly towards me—“I saw you come out of the side entrance! You know—and so, if you please, tell me. What has happened in that house?”

Satisfied that I should not let her out of my sight:

“A gentleman known as Mr Victor has died.”

“He is dead?”

“Yes.”

Her slim fingers closed on my arm with a surprisingly strong grip.

“Thank you.” Dark lashes were raised; she flashed up at me an enigmatical glance. “Good night!”

“Just a moment!” I grasped her wrist. “Please don’t run away so quickly.”

At which she lifted her voice:

“Let me go! How dare you! Let me go!”

Two men detached themselves from the group of loiterers and dashed in our direction. But the behaviour of my beautiful captive, who was struggling violently, was certainly remarkable. Pressing her lips very close to my ear:

“Please let me go!” she whispered. “They will kill you. Let me go! It’s no use!”

I released her and turned to meet the attack of two of the most ferocious-looking ruffians I had ever encountered. They were of Mongolian type with an incredible shoulder span in proportion to their height. I had noticed them in the group about the door but had not seen their faces. Viewed from the rear with their glossy black hair they might have been a pair of waiters from some neighbouring hotel. Seen face to face they were altogether more formidable.

The first on the scene feinted and then by a trick, which fortunately I knew, tried to kick me off my feet. I stepped back. The second was upon me. Other loiterers were surrounding us now and I knew that I was on the unpopular side. But I threw discretion to the winds. Until I could turn my face from these two enemies I had no means of knowing what had become of the girl. I led off with a straight left against my second opponent.

He ducked it perfectly. The first sprang behind me and seized my ankles. The house door was thrown open and Inspector Leighton raced down the steps. Fey came up at the double, so did the driver of the police car. The attack ceased. I spun around, and saw the black-haired men sprinting for the corner.

“After that pair,” cried Leighton gruffly. “Don’t lose ’em!”

The police driver and Fey set out.

“ ’E was maulin’ ’er about!” growled one of the loiterers. “They was in the right. I ’eard ’er cry out.”

But the girl with the amethyst eyes had vanished…

CHAPTER FIVE

THREE NOTICES

“She has got clear away,” said Nayland Smith, “thanks to her bodyguard.”

We stood in the library, Smith, myself, Mr Bascombe and Inspector Leighton. Sir James Clare was seated in an armchair watching us. Now he spoke:

“I understand, Smith, why General Quinto came from Africa to the house of his old friend, secretly, and asked me to recall you for a conference. This is a very deep-laid scheme. You are the only man who might have saved him—”

“But I failed.”

Nayland Smith spoke bitterly. He turned and stared at me. “It appears, Kerrigan, that your charming acquaintance who so unfortunately has escaped—I am not blaming you—differs in certain details from Mr Bascombe’s recollections of the general’s visitor. However, it remains to be seen if they are one and the same.”

“You see,” the judicial voice of the home secretary broke in, “it is obviously impossible to hush this thing up. A post-mortem examination is unavoidable. We don’t know what it will reveal. The fact that a very distinguished man, of totally different political ideas from our own, dies here in London under such circumstances is calculated to produce international results. It’s deplorable—it’s horrible. I cannot see my course clearly.”

“Your course, Sir James,” snapped Nayland Smith, “is to go home. I will call you early in the morning.” He turned. “Mr Bascombe, decline all information to the press.”

“What about the dead man, sir?” Inspector Leighton interpolated.

“Remove the body when the loiterers have dispersed. Report to me in the morning, Inspector.”

It was long past midnight when I found myself in Sir Denis’ rooms in Whitehall. I had not been there for some time, and from my chair I stared across at an unusually elaborate radio set with a television equipment.

“Haven’t much leisure for amusement, myself,” said Smith, noting the direction of my glance. “Television I had installed purely to amuse Fey! He is a pearl above price, and owing to my mode of life is often alone here for days and nights.”

Standing up, I began to examine the instrument. At which moment Fey came in.

“Excuse me, sir,” he said, “electrician from firm requests no one touch until calls again, sir.”

Fey’s telegraphic speech had always amused me. I nodded and sat down, watching him prepare drinks. When he went out:

“Our return journey was quite uneventful,” I remarked. “Why?”

“Perfectly simple,” Smith replied, sipping his whisky and soda and beginning to load his pipe. “My presence tonight threatened to interfere with the plot, Kerrigan. The plot succeeded. I am no longer of immediate interest.”

“I don’t understand in the least, Smith. Have you any theory as to what caused General Quinto’s death?”

“At the moment, quite frankly, not the slightest. That indefinable perfume is of course a clue, but at present a useless clue. The autopsy may reveal something more. I await the result with interest.”

“Assuming it to be murder, what baffles me is the purpose of the thing. The general’s idea that he could hear drums rather suggests a guilty conscience in connection with some action of his in Africa—a private feud of some kind.”

“Reasonable,” snapped Smith, lighting his pipe and smiling grimly. “Nevertheless, wrong.”

“You mean”—I stared at him—“that although you don’t know how you do know why General Quinto was murdered?”

He nodded, dropping the match in an ash tray.

“You know of course, Kerrigan, that Quinto was the right-hand man of Pietro Monaghani. His counsels might have meant an international war.”

“It hangs on a hair I agree, and I suppose that Quinto, as Monaghani’s chief adviser, might have precipitated a war—”

“Yes—undoubtedly. But what you don’t know (nor did I until tonight) is this: General Quinto had left Africa on a mission to Spain. If he had gone I doubt if any power on earth could have preserved international peace! One man intervened.”

“What man?”

“If you can imagine Satan incarnate—a deathless spirit of evil dwelling in an ageless body—a cold intelligence armed with knowledge so far undreamed of by science—you have a slight picture of Doctor Fu-Manchu.”

In my ignorance I think I laughed.

“A name to me—a bogey to scare children. I had never supposed such a person to exist.”

“Scotland Yard held the same opinion at one time, Kerrigan. But you will remember the recent suicide of a distinguished Japanese diplomat. The sudden death of Germany’s foremost chemist, Erich Schaffer, was frontpage news a week ago. Now—General Quinto.”

“Surely you don’t mean—”

“Yes, Kerrigan, the work of one man! Others thought him dead, but I have evidence to show that he is still alive. If I had lacked such evidence—I should have it now. I forced the general’s dispatch box, we failed to find the key. It contained three sheets of note paper—nothing else. Here they are.” He handed them to me. “Read them in the order in which I have given them to you.”

I looked at the top sheet. It was embossed with a hieroglyphic which I took to be Chinese. The letter, which was undated, was not typed, but written in a squat, square hand. This was the letter:

FIRST NOTICE

The Council of Seven of the Si-Fan has decided that at all costs another international war must be averted. There are only fifteen men in the world who could bring it about. You are one of them. Therefore, these are the Council’s instructions: You will not enter Spain but will resign your commission immediately, and retire to your villa in Capri.

President of the Seven

I looked up.

“What ever does this mean?”

“I take it to mean,” Smith replied, “that the first notice which you have read was received by General Quinto in Africa. I knew him, and he knew—as every man called upon to administer African or Asiatic people knows—that the Si-Fan cannot be ignored. The Chinese Tongs are powerful, and there is a widespread belief in the influence of the Jesuits; but the Si-Fan is the most formidable secret society in the world: fully twenty-five per cent of the coloured races belong to it. However, he did not resign his commission. He secured leave of absence and proceeded to London to consult me. Somewhere on the way he received the second notice. Read it, Kerrigan.”

I turned to the second page which bore the same hieroglyphic and a message in that heavy, definite handwriting. This was the message:

SECOND NOTICE

The Council of Seven of the Si-Fan would draw your attention to the fact that you have not resigned your commission. Failing your doing so, a third and final notice will be sent to you.

President of the Seven

I turned to the last page; it was headed Third Notice and read as follows:

You have twenty-four hours.

President of the Seven

“You see, Kerrigan,” said Nayland Smith, “it was this third notice”—which must have reached him by district messenger at Sir Malcolm’s house—“which produced that state of panic to which Bascombe referred. The Council of Seven have determined to avert war. Their aim must enlist the sympathy of any sane man. But there are fourteen other men now living, perhaps misguided, whose lives are in danger. I have made a list of some of those whose removal in my opinion would bring at least temporary peace to the world. But it’s my job at the moment to protect them!”

“Have you any idea of the identity of this Council of Seven?”

“The members are changed from time to time.”

“But the president?”

“The president is Doctor Fu-Manchu! I would give much to know where Doctor Fu-Manchu is tonight—”

And almost before the last syllable was spoken a voice replied:

“No doubt you would like a word with me, Sir Denis…”

For once in all the years that I knew him, Smith’s iron self-possession broke down. It was then he came to his feet as though a pistol shot and not a human voice had sounded. A touch of pallor showed under the prominent cheekbones. Fists clenched, a man amazed beyond reason, he stared around.

I, too, was staring—at the television screen.

It had become illuminated. It was occupied by an immobile face—a wonderful face—a face that might have served as model for that of the fallen angel. Long, narrow eyes seemed to be watching me. They held, my gaze hypnotically.

A murmur, wholly unlike Smith’s normal tones, reached my ears… it seemed to come from a great distance.

“Good God! Fu-Manchu!”