Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

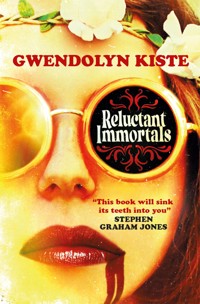

For fans of Mexican Gothic, a harrowing, sultry horror novel about the forgotten women in Dracula and Jane Eyre as they combat the toxic men intent on destroying their lives. Los Angeles, 1967. Lucy Westenra and Bertha Mason – the forgotten women in Dracula and Jane Eyre – have been existing as undead immortals for centuries, unable to die and still tormented by the monsters that made them. Lucy has long fought against Dracula's intoxicating thrall, refusing his charismatic darkness and her ensuing appetite for blood. Bertha Mason, the madwoman in the attic, is still pursued from afar by Mr Rochester, who wants to add her to his collection of devoted female followers. Then Dracula and Rochester make a shocking return in San Francisco. To finally write their own story, Lucy and Bertha must boldly reclaim their stories from the men who tried to erase them in this harrowing gothic tale of love, betrayal and coercion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“This is a black rose petal crushed for generations in a mouldering Victorian novel, one that’s now steadily trickling blood down the spine, those drops collecting not in a cupped palm but the sharp corners of a mouth. This book will sink its teeth into you.”

STEPHEN GRAHAM JONES

“A sharp, feminist reclaiming… The perfect blend of darkness and dark humor – by turns biting, heartbreaking, and uplifting.”

A.C. WISE

“Lucy and Bee are the Thelma and Louise of the vampire pack… A horror story with bite and heart, conjuring an engrossing novel that I devoured, unable to put it down.”

LISA KRÖGER

“Scary, stylish, and exciting, this novel frees two of Gothic literature’s most libelled anti-heroines and gives their tales a powerful new ending.”

WENDY N. WAGNER

“Kiste weaves Gothic classics together with mid-century grit in a story that pulls women out of the shadows of their oppressors and into the light from the fire of their own rage. Kiste is a genius of critical entertainment.”

SARAH READ

“Reluctant Immortals is a kaleidoscopic, rot-fueled joy to read – the Stoker and Bronte sequels I never knew I needed. I loved it.”

DAWN KURTAGICH

“What begins as a clever conceit becomes much more when Kiste places this battle for self-determination against the backdrop of 1967 San Francisco.”

S.P. MISKOWSKI

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Reluctant Immortals

Print edition ISBN: 9781803362908

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803362915

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition November 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© Gwendolyn Kiste 2022 All rights reserved.

Gwendolyn Kiste asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Charlotte and BramThank you

It’s almost sundown in Los Angeles, and Dracula’s ashes won’t shut up.

He’s been at it since yesterday, calling out for me, calling out for anyone, his voice strained and distant, so soft I can never quite make out the words, so unforgiving I can never escape him. I cover my ears and recite a prayer I no longer believe, but it’s not enough to blot out the sound of him.

I have to try something else. I have to bury him. Again.

So now here I am, standing in the shadow of the Hollywood sign, a shovel in one hand, an urn of his ashes in the other. Up here on Mount Lee is as good a place as any to lay him to rest. It’s remote and hard to get to, and at the very least, I won’t forget where I put him.

The last bits of daylight have dissolved across the horizon, and I move through the overgrown weeds, picking a spot between the letters Y and W where the earth is soft and malleable.

Then I start digging.

Below me, the city buzzes pleasantly like a swarm of locusts. It’s the middle of June, the heat creeping in, and this isn’t how I wanted to spend my evening. Of course, I never want to spend my nights with him, but what I want doesn’t count for much.

As I work, the urn quivers on the earth next to me. The color of midnight, it’s not much bigger than a man’s fist. This isn’t the only urn of Dracula’s ashes, but right now, it’s the only one that matters. It’s the loudest of the bunch, that’s for sure. The others back at the house are usually content to keep quiet, murmuring no louder than common sleepwalkers, but not this one. It’s made up its mind to make my life hell. And I’ve made up my mind to do the same to him.

Another whisper from the urn, and I nudge it with my heel.

“Stop,” I say, my feet sinking in the mud. I hiked all the way here in my pilgrim pumps and satin dress, up the Santa Monica Mountains, even snagging my hem on a low-lying shrub. Dracula doesn’t care. He just keeps at it. He’s never been very good at keeping his mouth shut. Not that he’s really got a mouth, not now, not after I buried that stake in his cold, dead heart.

Anybody who knows the story—and let’s face it: these days, who doesn’t know the story?—will always wonder the same thing. He’s dead, right? Turned to dust decades ago? Shouldn’t everyone be safe now?

Please. As if men like him are ever that easy to vanquish. They always figure out the best way around the rules, bending the world in their favor. For most of us, death is the undeniable end. For him, it’s only a minor inconvenience.

A sharp breeze cuts through the dusk, rattling the letters in the sign like restless bones. The air harsh and sweet, I close my eyes, the buzz of the city fading away. That’s when I hear them. All the sweet heartbeats in Los Angeles, thrumming inside me at once. They waft up from the valley like steam, and my skin hums, my teeth sharpening, reminding me of what I am, what he’s done to me.

The sound of Dracula rises again, almost singing now, and even though I still can’t hear him clearly, I can guess what he’s saying.

“Take what belongs to you, Lucy,” he used to tell me. “Take anything you want.”

I do my best not to listen. My hands blistered, I keep digging, promising myself the same thing as always: that I won’t end up like him. I won’t become a monster. I’d rather waste away, which is exactly what I’m doing, hunger gnawing at me night after night, my stomach aching and cavernous and raw. It turns out a vampire can live a very long time without taking a drink. It just hurts like hell to do it.

I grimace, eager to get this over with, as a shadow passes over my face.

“Are you all right?” A voice materializing, thin as mist, next to me. I turn and see her, moving like a phantom in the twilight, so quiet I never heard her coming.

I smile. “Hello, Bee.”

She grins back. “Hello yourself.”

The melody of the city fades to static, and it’s just me and her and these ashes that won’t ever rest. Her head down, Bee huddles close to me, and the hollowness, the silence within her, reminds me of how we’re connected. There’s no heartbeat inside either of us. We’re at once alive and dead, even though we aren’t the same. Bee’s no vampire like me. She died and came back a different way, a way she doesn’t like talking about.

That means Dracula’s not her problem, he’s mine, so I try to keep her out of this. When I left, she was waiting in the car, back where I parked it on the street, in a quaint little neighborhood where the only boogeyman they know is rising inflation.

“You didn’t have to come all the way up here,” I say, digging a little faster now.

“Figured you could use the company.” Bee fidgets in the dirt next to me. “Besides, I’d rather not be alone.”

An uneasy silence twists between us. I’m not the only one with secrets.

The Hollywood sign looms over us, the rusted sheet metal trembling in the breeze. For a lonesome town, this might be its most lonesome landmark. At the far end, the H rocks back and forth, the same letter actress Peg Entwistle chose when she took a swan dive off the sign back in ’32. That was thirty-five years ago, ancient history in this town, and by now, everyone’s mostly forgotten her. That’s how it goes here. This is a glittering city haunted by the ghosts of dead girls and dead dreams. In that way, Bee and I fit right in.

The shovel hits sandstone, and this is it, the best I can do. My hands shaking, I deposit the urn of Dracula into the dark. There are no words of prayer and no curses, either. Just a flick of the wrist, and he’s nestled in the ground. I fill the hole back in, almost frenzied, my fingernails limned with darkness, my pumps pounding on the earth, packing down the soil.

Bee helps too, kicking some dirt into the grave. “How long do you think he’ll stay put?”

I shake my head. “Not long.”

Beneath our feet, I already feel him, restless as always. He’ll work his way back up, bit by bit, crawling like an earwig, the urn writhing in the earth on his command.

I grind my heel into the ground one last time. “Goodbye,” I say, but he and I both know it’s a lie. I’ll come back at the end of the week. It isn’t safe to leave him alone for long. At least this way, though, I get a few days’ reprieve from his complaining.

It’s darker now, and Bee and I trek back to the car. Halfway down the hill, she takes off her shoes, lemon-yellow Mary Janes we picked up last year at the Salvation Army.

“Easier than hiking in heels,” she says, and I laugh and do the same, the two of us barefoot in the trail dust, sneaking through the Santa Monica Mountains, dragging the shovel behind us. There are snakes in these parts, but they slither beneath the sagebrush when they see us coming.

We emerge at last under a streetlight, and parked on Mulholland is our Buick LeSabre, rust on the bumper, one taillight cracked.

Bee tosses me the keys, and we both slide in, the torn leather seats spewing yellow foam. It takes two stalled starts before the engine roars to life. The car’s already seven years past its prime, but who’s counting? Not us, not when we have less than a hundred dollars in cash to our names and can’t afford a new ride. This is the only thing we’ve got, so we make the best of it. With the canvas top pulled down, we rocket toward the state highway, the California evening settling around us like a false promise.

As the oleander trees rush past, Bee twists the chrome dial on the radio, and we sit back, listening in. It’s the same news as always. The death toll in Vietnam. The people in power pretending to care. Nothing good ever happens here. Cape Canaveral launched Mariner 5 at Venus this morning, which makes sense, because the only way things might ever improve is to give up on this planet altogether.

“Do you think we could survive on Venus?” Bee asks.

I shrug. “I hear it’s made of fire.”

She exhales a laugh. “Aren’t we?”

Bee tips her head back, the wind rustling through her long, dark hair. The night’s cooling off already, and the canopy of trees draws us closer into its embrace. I wish we were safe here, but we’re not alone. We’re never alone, not really. Something’s always whispering after us, lingering on the breeze, hiding in the static of the radio. I press the gas pedal harder, ready to rev it so fast nothing could ever catch us, but that’s when I see it. The marquee emerging around the bend, the cornflower-blue neon flashing like a beacon.

Munroe’s Drive-In. Double screens, open seven days a week. Chockful of loud music, louder explosions, and images so bright they nearly blind us. This is exactly what Bee and I need. It’s the only way we’ve found to escape ourselves, to escape the past, if only for a few hours.

The engine turns over as we idle up to the ticket booth, its faded paint flecking off like chunks of dirty snow. Inside, hunched over in a folded chair is Walter, the purveyor of the place, his hair fright white, thick whiskers coming out both his ears. He squints into the convertible and brightens when he sees it’s us.

“Hello, girls,” he says, flashing us a toothy grin, oblivious as always. Bee and I have been coming here for ten years, neither one of us ever aging a day, but he doesn’t seem to notice. He’s just happy to have the patrons.

We pay our five dollars and rumble slowly into the lot over chunky gravel, pulling into the last spot in the front row. This speaker’s the best one in the place. Never been broken, not that we know of, and you can crank the volume high enough to drown out almost anything.

The first movie starts a minute later, barely long enough for us to turn off the engine. Walter must have been waiting for us. He knows we’re here every night, rain or shine.

Our eyes fixed on the screen, the trailers flash by, as Bee sits cross-legged in the passenger seat, her dusty pumps on the floor, her feet bare again. All around us, the scent of Pic permeates the air, everybody with a mosquito coil lit on their dashboards except for us. Bee and I don’t have to worry. We’re in the only car the bugs never bother. They know there are no signs of life here.

But there are signs of life elsewhere. Windows fogged up, heavy panting, the whole nine yards. Young couples necking in the back seats of their parents’ borrowed cars, their guards down, their pulses thrumming faster. My fingers clench tight on the steering wheel, the soundtrack of the movie fading out, everything fading, until all I hear are those rhapsodic heartbeats.

These eager lovers are easy pickings. Too easy. They’d never expect me, what I’d do to them. I could stroll right up to their cars and climb on in, and they wouldn’t even have time to open their mouths and scream before I’d open my mouth and make sure they never screamed again. Sometimes, I think I like coming here just to test myself, to prove I’m not a monster. I can sit right in the middle of a smorgasbord, and I won’t do a thing about it.

I look across the mountains in the dark, and there it is, hanging over me in the distance like the blade of a guillotine. The Hollywood sign. You can see it from all over town, peeking between buildings, shining through the smog. That means I can see him, too, the place where I’ve hidden him.

Seventy years, and what he did to me still feels as fresh as yesterday, every detail branded into my mind. The scent of roses, the scent of him, sweet and inviting, like a home I’d never known. The night it happened, there was no black cape or black bat or blood clotting Technicolor red across a crisp white blouse. It was far duller than that. Just me and him on an iron park bench at midnight. My broken curfew, his broken promise. A man who takes what he wants, and a girl who has to pay the price. That’s the way these stories always go.

The first movie ends, and the floodlights come up for intermission. The couples in the other cars climb out and stretch their legs, their bodies glistening with sweat, fresh hickeys on their necks. I watch them, thinking how quick it would be, how simple. One pointed glance from me, and they’d be under my sway, mine for the taking. Dracula’s voice ripples through me again.

Take what belongs to you, Lucy.

As though on his command, I fling open the car door, my whole body quivering.

Bee’s head snaps toward me, her dark eyes wide. “What’s wrong?” she asks, and under the weight of her stare, shame washes over me.

“Nothing,” I say. “I’m going to the concession stand. You want anything?”

“The usual,” she says, and hesitates. “You sure you’re okay?”

“I’m fine,” I say, and stumble out of the car and across the lot, past the flushed couples, past everything, not looking back, not even when I’m sure I hear something in the hills laughing at me.

When I get inside, the lobby’s empty: no heartbeats, no danger. Narrow and cramped, it’s not much more than a shack, fingerprints smearing the walls, half the overhead light fixtures burned out. A red velvet rope, matted and stained, snakes around from door to counter, even though there probably hasn’t been a line long enough to fill the place since Clark Gable was a matinee idol.

I follow the rope around and lean up against the counter, waiting until the side door creaks open and Walter hustles in, his breath rasping. He does it all around here—takes the admission, roasts the hot dogs, runs the projector. That’s because there’s nobody left to help him. He’s a widower from way back, his life a domino game of losses. His youth, his wife, his peace of mind. By the look of this place, it might be the next to go.

Still, he never stops grinning. “What can I do for you, Lucy?”

What I want isn’t on the menu, so I settle for ordering two medium Cokes and a popcorn, extra butter. Bee and I don’t need to eat—we don’t need much of anything—but going to the movies is all about make-believe, right?

His gnarled hands trembling, Walter fills two waxed cups with ice. “Glad you could make it out tonight,” he says. “Wednesdays are always slow around here. You know, just last week—”

And with that, he starts into his latest yarn about the patron who bought three boxes of Milk Duds and paid in pennies. I quiet my face, trying my best not to roll my eyes. Small talk. Why do people always make small talk? Sometimes it’s about the weather, sometimes a singer or television actor I’ve never heard of. Not that that means much. Perry Como is still modern to me.

As Walter chatters on, scooping yellow leavings from the bottom of the popcorn machine, I turn away, gazing out the smudged window in the lobby. Across the lot, Bee’s watching me from the Buick. She waves when she sees me looking, and I wave back, smiling.

Bee won’t come in here. She doesn’t like confined spaces, doesn’t like feeling trapped.

“Oh, did I tell you?” Walter nearly bursts toward me with excitement, his pulse surging. “My grandson Michael’s coming to visit. You remember, the one that just finished his tour overseas.”

I hesitate, something settling deep in my guts. “Of course,” I say. How could I not remember? Walter hasn’t stopped talking about his grandson ever since the draft notice landed in the mailbox like a grenade, shattering their lives into bits. This is the one bit of small talk I’d never deny him.

“He’ll be here tomorrow,” Walter continues, as I fork over a dollar, and he makes change, one careful nickel at a time. “I’ll be sure to introduce you to him.”

“If that’s what you want,” I say, even though I should tell him no. His grandson’s been at war, an ugly war, even uglier than most. He’s seen more death in two years than I’ve seen in two lifetimes. He doesn’t need to meet me, too.

Walter doesn’t understand that. When he looks at me, he sees what everyone else does: a perfectly fine young lady, red curls in her hair, red rouge on her cheeks. Never mind the dirt beneath her fingernails and the teeth that sharpen if you catch her on a bad night. He never seems to notice those things. Nobody does. That’s why I can hide in plain sight. Everything about me is a disguise.

The drinks and popcorn gathered up in my arms, I get back to the car just in time for the next film to start. A beach movie I never heard of called Don’t Make Waves. Bee and I clutch our drinks, downing them in a minute, barely tasting anything.

The movie drags on, Tony Curtis’s character pestering a pretty blonde who isn’t given much to do besides bounce around in a bikini. Sighing, I glance in the rearview mirror. Behind us on the other screen, it’s the latest James Bond film. You Only Live Twice. We’ll probably see that one tomorrow night. We see every movie that plays here. Anything to escape what’s waiting at home.

Or what’s waiting for us here. A change in the wind, and we’re suddenly not alone.

Bertha, a man’s voice calls out, sharp and cold as a fistful of straight pins.

It isn’t Dracula this time, and it isn’t for me. It’s for Bee. She seizes up in the passenger seat. No matter how many times this happens, she’s always caught off guard.

He comes at her again, louder and more determined. Where have you gone, Bertha?

She won’t look at me. She won’t look at anyone. Bee with her own secrets and a name she never uses anymore.

Bertha Antoinetta Mason. The so-called madwoman in the attic. The first wife of one Edward Fairfax Rochester. A man with a sprawling estate and a sprawling ego and a temper that could set the whole world on fire. She married him young, married foolishly, and when she wouldn’t bend to his will, pliable as clay in his calloused hands, he locked her away in an upstairs room before he went searching for someone else, a woman to replace her.

That was over a century ago, thousands of days separating her from him. He shouldn’t even remember her now. But men like him are never eager to lose what they consider theirs.

His cruel laughter lilts on the wind, and I fumble with the speaker, cranking up the volume, desperate to drown him out. This is one of his favorite tricks: calling her from afar, throwing his voice across the miles like a wicked ventriloquist. We have no idea where he is, but he can somehow always find us.

Bertha, he whispers again, and Bee grabs my hand, the two of us holding tight to each other. I look to the other cars, the couples in back seats blissfully unaware. Like always, nobody can hear him but us.

“Do you want to leave?” I ask, but Bee shakes her head.

“It won’t do any good,” she says, and she’s right. Nowhere is safe for us.

Bee and I wait, barely moving, until what’s left of his voice dissolves into the night. This is how it always goes—he never sticks around—but the damage is already done. For the rest of the film, she and I stare blankly at the screen, seeing nothing, hearing nothing, thinking only of the two men who won’t ever let us escape.

There are tales about Rochester and Dracula, books and movies, ones where Bee and I have been mostly written out, deleted from our own story, our own lives. Every time I turn around, it seems there’s another version of Dracula, another casting call for nubile young women, corseted and blushing and breathless for him. He’s become an unlikely hero, a bloodsucking James Bond, and I’ve become less than a footnote. The disposable victim who should have known better.

Bee’s fared even worse. In all the movies about her life, she’s no more than an extra locked away in a flimsy attic. She gets a few meager frames of screen time before a fire gobbles her up in the third act. She’s ash; she’s nothing; she’s an obstacle to overcome. She has to die so Rochester and his new wife can live. Bee and I are the same in this regard: the only way that others can have their happy ending is if we don’t get ours.

The end credits roll on the second film, all beachy sunsets and lovers united, and the floodlights come up again, for good this time, garish and accusing and spiriting us on our way. Walter waves goodbye from the ticket booth, and Bee and I drive home, midnight brimming all around us. The sky crackles, the heavy clouds threatening rain, but we don’t bother to put up the top for the convertible. Too claustrophobic for Bee. Besides, we both like the fresh air. We might not need to breathe anymore, but on cool summer nights like this, it’s nice to pretend.

We turn down Wilshire Boulevard, storybook houses whizzing past us in the dark. My entire body tenses. We’re almost there now, the one place I’ve been dreading all night.

Bee gazes at me, the glow of the passing streetlights flickering on her face. “We don’t have to go back yet,” she says. “Norm’s might still be open. We could hang out and drink coffee until tomorrow.”

She’s trying to buy us time. Buy me time. She knows what’s waiting for me.

“It’s okay,” I whisper.

Bee didn’t hide from her nightmare tonight. I shouldn’t hide from mine.

The car slows, and we reach a stone house veiled thick in shadows, dead ivy clinging to the facade. I pull into the long driveway, desiccated weeds sprouting up through the cracks in the cement, the empty swimming pool silent and gaping as an open grave.

Welcome home.

The engine cuts out, and Bee and I climb out of the car. On the cracked cobblestone path, we walk together, past the former garden, gray and thorny and crying out silently for help, everything fading here.

When we get to the front step, the air turns heavy and fetid, and once again, I want to run. I want to be anywhere but here.

Bee studies my face, her eyes shining and calm. “Are you sure?” she asks.

“Yes,” I say, and with a steady hand, I turn the key in the lock.

We open the door, and the rest of Dracula is waiting to greet us.

As we step into the house, the pieces of him murmur all around us, permeating every room like a sickly sweet cologne. Even locked inside his urns, he’s louder than he has any right to be.

If he’s still locked inside the other urns. I need to check on him. I need to make sure he hasn’t tried another escape.

Bee and I drift through the vestibule, past a decapitated statue of the Birth of Venus. (We didn’t do the beheading, by the way; it came like that with the house.) In the living room, the curtains flutter in the night breeze, and Bee crosses to an open window, gazing out at the skyline, glinting like faded diamonds in the distance.

It’s dark in here, so I strike a match and light a pair of taper candles. This is all we have. There’s no electricity running to the house. No heat or water, either. We can’t afford utilities, but then why would we need them? Being dead means being frugal.

Bee watches me with the match, her lips pursed. She doesn’t mind candles, but she never lights them. That’s because she won’t touch fire. Not anymore, not after what happened the last time she struck flint against steel.

“Sometimes,” she once told me, “it still feels like my skin is burning.”

Then she said no more about it, and I didn’t ask.

My hands steady, I leave one candle on the antique desk and take the other to guide my way. “I’ll be back in a moment.”

Bee looks at me, her brow furrowed. “Do you need help?”

“I’m fine,” I say, and even though it’s a lie, she pretends to believe me.

“Good luck,” she says, and I’m off on my nightly errand. Checking on these murmuring remains. Guarding the urns of Dracula.

For seventy years, I’ve separated him from himself, his ashes never kept in one place, never even kept in the same room. He’s too powerful that way. If I put him in a single vessel, he’d break free and cobble himself together in an instant. Instead, the urns are scattered throughout the house like silly knickknacks.

The first urn’s in the parlor, locked inside a small glass cabinet, the kind that used to display odd Victorian artifacts like narwhal horns or monarch butterflies. It’s the quietest urn in the house, and when I run my fingers along the outside of the clay, looking for cracks, for any sign of weakness, it barely quivers in reply.

When I get to the next one in the kitchen, I’m not so lucky. This urn’s in the wall behind the decommissioned icebox, nestled in the horsehair plaster, and as I yank it free, it shivers in my hands, practically sighing in ecstasy, the brush of my fingertips giving it a cheap little thrill. I hold back a gag, scanning it quickly for flaws. A chip on the rim perhaps or a half-unscrewed lid or a thin fracture in the clay like the fault line beneath Los Angeles. Fortunately, there isn’t anything to worry about tonight. No cracks, no movement, nothing alarming at all. I place the urn back where it belongs, inside the wall.

That leaves the last one. The worst one. It’s always waiting for me, pushed to the back of the cellar. Because I’ve got no excuses left, I go to it now, through the door at the end of the hall and down the stairs, dread clenching in my throat.

In Los Angeles, basements are rare as coelacanths. It’s something about the waterline along the coast, the way the sea pushes in toward the land, stealing into places where it doesn’t belong. Bee and I got lucky with this house—or unlucky, depending on how you look at it. It’s not a very pretty cellar. The stone walls are slime and grit, and the splintered wooden stairs have no risers, the backs open to the darkness, to anything that wants to reach out and take hold of you.

I descend deeper into the bowels of the house, the gloom creeping closer. This single candle isn’t nearly enough to light my way, but it will have to do. Especially since I’m almost there.

The final urn is on the floor, trapped beneath an upside-down milk crate, the rusted wire like prison bars. I edge forward, but I don’t touch this one. I don’t even get too close. It isn’t safe, the outside of it hotter than the others, like a gas lantern left to burn all night. It never tries to speak. It only seethes, the rage in it so potent it chokes the air out of the room.

My head spins, and I steady myself against the oily stone wall. The weight of his wrath always makes me seasick standing still, everything in me heavy and dizzy and outsized.

This isn’t what I want, to be tethered to Dracula for eternity. I wish I could cast his remains out into the Pacific or seal him in concrete, leaving him behind, leaving him in the past, but that wouldn’t be enough to hold him. He’d escape in a day if I did.

It has to be these urns. They’re the only thing stopping him.

When we first moved in, Bee asked me if I wanted to leave the urns outside. Buried in the garden, maybe, or left in the bottom of the empty pool.

“We don’t have to invite him in,” she said, and even though I knew she was right, I brought him inside anyway. I might exile an urn for a little while, but it isn’t safe for all of him to be too far away for too long. Day or night, I need to keep him close. I need to watch him. That way, I can always be sure at least a part of him isn’t free. Some days, that’s the only comfort I have, knowing that I’ve prevented a monster from being unleashed on the world.

I retreat upstairs, back to the living room, and Bee looks up at me from the sofa.

“How was it?”

“The same,” I say, which is the best we can hope for.

A heavy breeze cuts through the air, and Bee’s face twists, as if in pain.

“Could you?” she asks, and motions to the other side of the room.

One of the windows has blown shut.

I hurry to it and fling it open again, moonlight pouring in. This is another of our rituals. We leave all the windows open, even in the dead of winter, even during the worst thunderstorms. Rainwater leaks down the sills, seeping into the plaster, the yellowed paint cracking and bubbling, but that doesn’t matter. Bee doesn’t like to feel closed in. A decade locked in an attic will do that to you.

“Thanks,” she says, calm settling over her as she leans back on the withering Queen Anne sofa.

“No problem,” I say. I’ll do anything I can for her. She’ll do the same for me. Bee, my best friend, my only friend, the two of us sisters not by blood but by circumstance. We’ve been unlikely roommates for decades, ever since we stumbled upon each other outside London, no money in our pockets and no pulse in our veins.

“Are we the same?” she asked as we sat together at the St Katharine Docks, watching the ships come and go in the dark. I wanted to tell her yes, but it wasn’t true. Bee’s never been like me. There’s no bloodlust in her heart, no faint scar on her throat. Like Dracula, Rochester did something to her, something violent, something arcane, but those men had different methods. Dracula stole me from my bed at midnight, but Rochester was always more elaborate than that, having a flair for the dramatic. He lured Bee all the way from her home in Spanish Town, Jamaica, carrying her across the Atlantic, just to lock her in that attic. Then when she finally escaped, when she burned her prison to ashes, he started calling out to her, searching the world for her. And he hasn’t stopped since.

His voice from earlier tonight still burns in my bones. “Where do you think he is?”

Bee hesitates, her hands clenched in her lap. “Too close.”

“In L.A.?”

“No,” she says, her mouth a harsh line. “But somewhere else in California.”

I nod, not asking any more. I’ve probably asked too much of her already.

The candles burn down to nothing, the breeze carrying the darkness into the room, and we know what that means: it’s time to call it a night. Another day of eternity crossed off the list.

Upstairs in the hall, Bee glances back from her bedroom doorway.

“Good night, Lucy,” she says.

“Good night, Bee.”

She leaves her door open, anything to keep the claustrophobia from seeping in, but when I get to my room, I lock myself in tight. Anything to keep Dracula out.

In the dark, I kick off my shoes and curl up on my dusty four-poster bed. I don’t own a coffin, never have. I also don’t sleep during the day. I don’t need to sleep much at all, so long as I’m not like him, wasting all my precious energy stalking unsuspecting victims. It’s remarkable how much spare time you have when you don’t fritter it away on being a monster.

But that’s all he is, all he knows. His whispers linger on my skin, and even though the pieces of him are downstairs, a whole floor and a locked door separating us, it still feels like he’s right here, in the same bed with me, his breath hot on the back of my neck, his fingertips tracing a path up my thigh. I can’t escape him. He’s everywhere at once.

Defiant to the last, I close my eyes and drift out of myself, out of my body, back to the places I came from. Across a continent, across an ocean, back to England. Past Carfax Abbey, long since abandoned, and over the house where I grew up, where I died, curled in a bed not so different from this one.

I drift on, through the streets of London, down back alleys and into the gloom where nobody goes. At least almost nobody. There’s someone else with me now, someone I haven’t heard from in a very long time.

Miss Lucy, the voice singsongs, slicing through the dark like a dull knife. Where are you, lovely?

Renfield. He materializes like fog in my mind. His clothes are tattered, his face obscured, his appetite for strange creatures unabated. If I look closely, I can see a cockroach leg, thinner than a toothpick, stuck between his molars. I do my best not to look closely.

He’s calling me from afar, lingering like a specter in the margins of the city. He shouldn’t still be alive, but then again, neither should I.

Even after all these years, Renfield and I have never met, but we know of each other anyhow. Through whispers and rumors and visions we can’t escape. When we close our eyes, we can both see it. The past, as though it’s still happening. I’m the one Dracula chooses first, plucked from my bedchamber like a daisy in May, and Renfield is the one he casts aside, a useless weed, a vestigial limb.

You never realized how lucky you were, Renfield says, gnashing his teeth in envy, and I wonder what he knows of luck or love or anything else.

He’s not a vampire, never has been. He’s a drudge, a thrall, mesmerized against his will, powerless and lost. So long as I don’t call back to him, he can’t see me the way I see him. That doesn’t stop him from trying, his graying eyes staring into the gloom, searching for me. Or rather, searching for what I have.

Master, he whispers, but before the urns can try to answer, I open my eyes and let him slip away.

Shivering, I bolt up in bed. I’m alone now. Dracula’s receded from the room, and there’s a yawning emptiness in his wake. An emptiness inside me, too. I hate the way he comes and goes, the way he still claims me for his own, how I can’t stop him even when I’ve got him captured. Rage rises in the back of my throat, acrid and stifling, and I can’t sit still. My blanket gathered up around me, I wander to the window. It’s quiet outside. Hollywood is settling down for the night. Only the glitzy denizens of Chateau Marmont are still up at this hour.

And maybe something else too. A shadow’s moving at the edge of the yard, the figure lithe and close to the ground. A coyote maybe, come up from the canyon, prowling for squirrels or stray cats.

I grit my teeth. “Go away,” I whisper, as it rustles past the weeds, still hidden from view. I’ve never liked coyotes. Too much like wolves, and wolves were always Dracula’s favorite. His “children of the night,” he called them. What a weirdo.

I wait at the window, listening for a howl, listening for hours, but whatever the animal is, it doesn’t return.

* * *

I wake up hungry.

It’s Thursday. Another day, another tally mark. I slink out of my tangled bedsheets. My shoes are somewhere on the floor where I left them, dirt from the Hollywood sign still caked around the heels. But as I lean down to search, bits of daylight creep across the room, and my chest constricts. I forgot to close the curtains last night.

My eyes bleary, I tiptoe to the window, as though I can sneak up on the day. With a careful hand, I reach toward the curtain, but a sliver of morning hits my face anyhow, and I flinch, nearly crying out, my mind whirling, my flesh tightening on my bones. There’s pain, but not the kind you might expect.

Sunlight doesn’t kill us. It never has. That wasn’t one of the original rules, but these stories become twisted, don’t they? They take on a mind of their own, and suddenly, you’re living in someone else’s invention of what you should be.

But here’s the thing: the sun does something else, something almost worse. It takes me away from here, pulling me into the past, putting images in my mind I’d rather forget. I see Dracula, the way he looked the night we met. So prim, so proper, so appallingly handsome. His scent like ash and roses, like a fistful of coffin dirt.

“Good evening, Miss Lucy,” he’d said, and I hate this part. I hate remembering how I swooned for him. How I believed him. The worst mistake I’ve ever made was trusting someone who only saw me as temporary.

And he’s not the only one awakening inside me. Mina’s with me too, back when we were only foolish girls, too young to know we should be afraid. Her fresh face is so gauzy in my memory that it’s almost lost to time. The face of my first friend, my only friend other than Bee. I see the garden maze where Mina and I used to giggle and run and share our secrets, the two of us weaving blooms of wisteria through our long hair.

“Let’s never grow old,” she would whisper, and I’d squeeze her hand and promise, never realizing the price I’d pay for keeping up my end of the bargain.

These memories burn in me, brighter than a hundred suns, and I don’t want this. I don’t want to remember. At last, I take hold of the curtains, and with my fingers clenched, knuckles white, I yank them closed. Then I collapse to the floor, my head in my hands.

I want to crawl back into bed and not leave this room at all today, but that won’t happen. Through the closed door, I hear her. Bee, battling her own past. Down the hall, she’s having another nightmare.

When I get to her, she’s thrashing in her bed, her limbs gone wild, her face twisted.

“It’s all right, it’s all right,” I keep saying, perched on the rim of the mattress. I put one hand on her arm, and instantly, I feel it there.

The thing crawling beneath her skin, thin as worms, tough as iron.

This is what Rochester did to Bee. What that attic in Thornfield Hall did.

“I barely remember it,” she always tells me. But sometimes, when she’s having a nightmare, she’ll say things that don’t make sense.

“Don’t let it get me, Edward,” she wheezes. “Please don’t do this to me.”

It was hiding in that attic where he imprisoned her. Something that got into him and got into Bee, too. That’s why neither one of them have died. The secrets of that burned-down house are keeping them alive.

There are so many things she still won’t tell me. There are things I haven’t told her, too. It’s a promise we made to each other the night we met: to not ask questions we aren’t eager to answer.

“Wake up, Bee,” I whisper, and with a final thrash, her body goes still, and she opens her eyes.

“Did it happen again?” she asks, and I nod.

She sits up, wiping salt tears from her cheeks. The skin on her arms is quiet now, no more crawling, no more movement. The thing inside her has settled down, retreating deeper into her body.

“I shouldn’t have slept in so late,” she says, as if that’s to blame.

I start to say something, to tell her it’s okay, but Bee’s too quick for me. She’s up and out of bed, rushing downstairs, determined to make up for lost time. I linger in the doorway, listening to her dashing back and forth through all the rooms, into the parlor and the hallway and settling finally in the kitchen. By the time I come down, the house is quiet and dark. She’s already tugged all the curtains closed, sealing out the worst of the sunlight. This is our compromise. The windows stay open for her, the curtains stay closed for me. We help each other. We’re only safe if we’re in this together.

And we’re only safe if we keep to our routine. It’s been a few hours, so I check on the urns again.

“He hasn’t made a peep,” Bee says brightly when I inspect the one behind the icebox in the kitchen.

I watch her at the counter, polishing silver and porcelain and brass for the imaginary guests we’ll never have. “You don’t have to keep an eye on him,” I say. “He’s not your responsibility, Bee.”

She shrugs. “It’s fine,” she says, as if it’s a perfectly normal request, asking your roommate to babysit the ashes of your ex.

The day already heavy in my bones, I go to the other urns, first in the parlor and then the cellar. At the bottom of the rickety steps, I hesitate, staring at it. At him.

“Why won’t you stay dead?” I whisper, and it’s the same question Dracula could ask me. I try not to speak too loudly. I don’t want Bee to hear. I don’t want her to know I still talk to him, still have these useless conversations with the man who murdered me.