Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

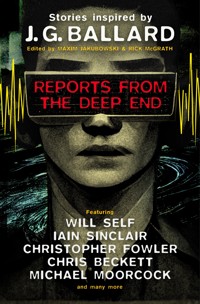

A fascinating and unsettling anthology of 32 science fiction short stories in tribute to the prophetic dystopias of New Wave sci-fi pioneer, and literary titan of the twentieth century, J. G. Ballard—featuring Will Self, Iain Sinclair, Christopher Fowler, Chris Beckett, and a new Jerry Cornelius story from Michael Moorcock. Few authors are so iconic that their name is an adjective – Ballard is one of them. Master of both literary and science fiction, his novels such as Empire of the Sun, Crash and Cocaine Nights show a world out of joint – a bewildering, alienating and yet enthralling place. From his rapturously weird takes on contemporary reality to his classic dystopias like The Drowned World and High Rise, Ballard's legacy shaped the future of literature. This first-of-its-kind anthology, featuring our greatest literary and science fiction authors, pays tribute to the unique visions of humanity's uncanny and uneasy clash with the future – our empires of concrete – seen through the warped lens of J. G. Ballard. Edited by renowned editors Maxim Jakubowski and Rick McGrath, this collection includes stories by: • Will Self • Iain Sinclair • Christopher Fowler • Chris Beckett • Michael Moorcock • Jeff Noon • Preston Grassmann • Toby Litt • Christine Poulson • David Gordon • Hanna Jameson • James Lovegrove • Ramsey Campbell • Barry N. Malzberg • Paul Di Filippo • Samathan Lee Howe • Nick Mamatas • Adrian McKinty • Rhys Hughes • Adrian Cole • Pat Cadigan • Adam Roberts • George Sandison • Geoff Nicholson • A.K. Benedict • Andrew Hook • David Quantick • Lavie Tidhar • James Grady

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 738

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

INTRODUCTIONMaxim Jakubowski & Rick McGrath

CHRONOCRASHJeff Noon

THE ASTRONAUT GARDENPreston Grassmann

ROADKILLToby Litt

THE LAST RESORTChristopher Fowler

WHITEOUTRick McGrath

A FREE LUNCHChristine Poulson

SELFLESSNESSDavid Gordon

ART APPChris Beckett

THE BLACKOUTSHanna Jameson

THE HARDOON LABYRINTH BY J.G. BALLARDMaxim Jakubowski

OPERATIONSWill Self

PARADISE MARINAJames Lovegrove

THAT’S HANDYRamsey Campbell

SUBTITLES ONLYBarry N. Malzberg

THE DREAM-SCULPTOR OF A.I.P.Paul Di Filippo

THE WAY IT ENDSSamantha Lee Howe

FIFTY MILLION ELVIS FANS CAN’T BE WRONGNick Mamatas

A LANDING ON THE MOONAdrian McKinty

THE GO PLAYERSRhys Hughes

THE NEXT TIME IT RAINSAdrian Cole

THE JANUARY 6, 2021 WASHINGTON DC RIOT CONSIDERED AS A BLACK FRIDAY SALEPat Cadigan

DEBTS INCORPORATEDAdam Roberts

LONDON SPIRITIain Sinclair

MAGIC HOURGeorge Sandison

DRIFTGeoff Nicholson

THEY DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY THEREA.K. Benedict

THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENTAndrew Hook

CHAMPAGNE NIGHTSDavid Quantick

TEDDINGTON LOCKLavie Tidhar

THE MISSISSIPPI VARIANTMichael Moorcock

THE NEXT FIVE MINUTESJames Grady

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Also available from Titan Books

A UNIVERSE OF WISHES: A WE NEED DIVERSE BOOKS ANTHOLOGY

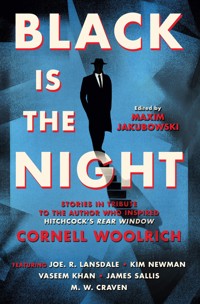

BLACK IS THE NIGHT: STORIES INSPIRED BY CORNELL WOOLRICH

CHRISTMAS AND OTHER HORRORS

CURSED: AN ANTHOLOGY

DARK CITIES: ALL-NEW MASTERPIECES OF URBAN TERROR

DARK DETECTIVES: AN ANTHOLOGY OF SUPERNATURAL MYSTERIES

DAGGERS DRAWN

DEAD LETTERS: AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE UNDELIVERED, THE MISSING AND THE RETURNED…

DEAD MAN’S HAND: AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE WEIRD WEST

ESCAPE POD: THE SCIENCE FICTION ANTHOLOGY

EXIT WOUNDS

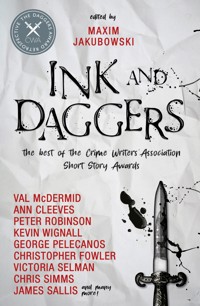

INK AND DAGGERS: THE BEST OF THE CRIME WRITERS’ ASSOCIATION SHORT STORY AWARDS

IN THESE HALLOWED HALLS: A DARK ACADEMIA ANTHOLOGY

INVISIBLE BLOOD

ISOLATION: THE HORROR ANTHOLOGY

MULTIVERSES: AN ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE REALITIES

NEW FEARS

NEW FEARS 2

OUT OF THE RUINS: THE APOCALYPTIC ANTHOLOGY

PHANTOMS: HAUNTING TALES FROM THE MASTERS OF THE GENRE

THE MADNESS OF CTHULHU ANTHOLOGY (VOLUME ONE)

THE MADNESS OF CTHULHU ANTHOLOGY (VOLUME TWO)

VAMPIRES NEVER GET OLD

WASTELANDS: STORIES OF THE APOCALYPSE

WASTELANDS 2: MORE STORIES OF THE APOCALYPSE

WASTELANDS: THE NEW APOCALYPSE

WHEN THINGS GET DARK: STORIES INSPIRED BY SHIRLEY JACKSON

WONDERLAND: AN ANTHOLOGY

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

REPORTS FROM THE DEEP END

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363172

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363189

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: November 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

INTRODUCTION © Maxim Jakubowski & Rick McGrath 2023

CHRONOCRASH © Jeff Noon 2023

THE ASTRONAUT GARDEN © Preston Grassmann 2023

ROADKILL © Toby Litt 2023

THE LAST RESORT © Christopher Fowler 2023

WHITEOUT © Rick McGrath 2023

A FREE LUNCH © Christine Poulson 2023

SELFLESSNESS © David Gordon 2023

ART APP © Chris Beckett 2023

THE BLACKOUTS © Hanna Jameson 2023

THE HARDOON LABYRINTH BY J.G. BALLARD © Maxim Jakubowski 2023

OPERATIONS © Will Self 2023

PARADISE MARINA © James Lovegrove 2023

THAT’S HANDY © Ramsey Campbell 2023

SUBTITLES ONLY © Barry N. Malzberg 2023

THE DREAM-SCULPTOR OF A.I.P. © Paul Di Filippo 2023

THE WAY IT ENDS © Samantha Lee Howe 2023

FIFTY MILLION ELVIS FANS CAN’T BE WRONG © Nick Mamatas 2023

A LANDING ON THE MOON © Adrian McKinty 2023

THE GO PLAYERS © Rhys Hughes 2023

THE NEXT TIME IT RAINS © Adrian Cole 2023

THE 6 JANUARY 2021 WASHINGTON DC RIOT CONSIDERED AS A BLACK FRIDAY SALE © Pat Cadigan 2023

DEBTS INCORPORATED © Adam Roberts 2023

LONDON SPIRIT © Iain Sinclair 2023

MAGIC HOUR © George Sandison 2023

DRIFT © Geoff Nicholson 2023

THEY DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY THERE © A.K. Benedict 2023

THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT © Andrew Hook 2023

CHAMPAGNE NIGHTS © David Quantick 2023

TEDDINGTON LOCK © Lavie Tidhar 2023

THE MISSISSIPPI VARIANT © Michael Moorcock 2023

THE NEXT FIVE MINUTES © James Grady 2023

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI & RICK MCGRATH

When a writer dies, their cultural and artistic influence can often wane rapidly; in the case of J.G. Ballard, who passed away in 2009, his work and ideas are still strongly reflected in the stories and novels of countless contemporary authors, not just in the field of science fiction but also within the mainstream literary domain. More than that, his shadow still dominates the cultural zeitgeist, due to the unique vision he had of the future, social developments, technology, and the media.

All Ballard’s titles remain in print globally and he continues to be an influence for many artists and writers around the world. There has been an unauthorized biography, a slew of articles and academic essays examining aspects of his work, and three film adaptations of his novels, with more in the pipeline. In addition, and this was the case even in his lifetime, artists in a variety of other media – music, the visual arts, even architecture – have openly admitted and celebrated his ongoing influence.

Indeed, his ongoing thematic distinctiveness has given rise to the adjective “Ballardian,” defined by the Collins English Dictionary as “resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in J.G. Ballard’s novels and stories, especially dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technology, social or environmental developments.” Certainly this offers a wide range of ideas and possibilities for other writers to explore.

Both editors of this collection have been not just admirers of Ballard’s work, but also influenced by him for almost as long as we remember. One, who began as just a reader, fortuitously became a good friend – to the extent of later travelling overseas to events and festivals in his company on many occasions and spending much enjoyable socialising, relaxing, indulging in an ever-fascinating dialogue and, happily, had the privilege of publishing some of his stories. The other is one of the world’s major collectors of his work, memorabilia, letters, and more, and created the annual Deep Ends anthology for the Terminal Press, which features new writings, both fiction and non-fiction, artwork, and personal and academic essays in a celebration of Ballard’s life and works.

Who better than us, we then thought, to assemble a collection of new stories by other writers – we were aware of the fact they were certainly in abundance – both inspired by or in homage to J.G. Ballard?

We cast our net wide and found out to our delight how far Ballard’s influence had reached, with esteemed authors we could not have initially guessed confessing to their admiration for Ballard’s heritage, alongside others who had already professed publicly what he meant for them.

No specific themes were imposed and we are in awe of the sheer breadth of territories, moods, subjects, tropes, and arcane nooks and crannies which they have unearthed in their sincere bid to evoke the spirit of Ballard in these wonderful new stories. They confirm our long-held conviction that he was without the shadow of a doubt the voice of the twentieth century and beyond, and that we are still, for good or bad, living in the fractured world he was so expert at evoking.

CHRONOCRASH

JEFF NOON

I stepped out of my vehicle and walked over to the crashed time machine. It was a saloon model, a Ford Tick-Tock, dark blue with silver trim. It had evidently been rammed from the side and pushed off the road, coming to rest in a shallow ditch. Flecks of orange paint spotted the door panel, the usual sign that Alexa Brandt had been involved. There was a basket in the front passenger footwell stuffed with picnic food, a vacuum flask and a scarf. The steering wheel was spattered with blood. But the occupants, whoever they were, had already disappeared. I had to wonder where they had ended up under the impact of the crash, in which period? Not too far back in time, I imagined, from the low level of damage to the bodywork and the dying flickers of temporal energy in the air. This was one of Brandt’s lesser ventures, a mild prang to fuel her next trip into the future. I needed to catch up with her before she did more serious damage, both to herself and to other drivers and passengers who happened to be on her route.

The vehicle was fading from my sight. I left it to its vanishing act and drove on until I reached the service station at Lower Peasbody. A light rain was falling. There was no sign of Brandt’s Estelle Vanguard in the car park. I bought a carton of juice and a chocolate bar in the Traveller’s Fare shop, feeding a sudden urge for sugar. In the gents I saw that my eyes were red, the skin below them puffy and bruised, a sure sign I was over the recommended number of daily trips forward and back. I walked halfway along the footbridge to look down at the steady stream of time machines in the past lane, all eager to get back home after a day’s work, their exhausts spewing out plumes of unwanted time. The future lane was less crowded at this time of the evening. A grey haze in the distance marked the borderline of tomorrow.

Alexa Brandt was an erratic driver, known for her sudden swerves, wild U-turns and off-road excursions, but now, as her obsession grew, she seemed determined to reach some as-yet-unknown forthcoming event. I could only wonder what awaited her in the long miles of the days ahead; and for myself, for I had willingly allowed Brandt’s urges to take up residence in my skull.

The rain had stopped. The road surface glistened wetly under the lights.

I checked my wristwatch. All three hands were trembling, as though time itself was nervous. The tremor passed from the dial into my body and for a moment I was disengaged, set adrift from the clock’s face. But the feeling passed quickly enough, and I made my way back to my trusty Dynasty 7. Easing the vehicle into a steady fifteen minutes per mile, I took the access road onto the motorway and set off for the near future, one eye on the lookout for any new crash sites.

* * *

Before Alexa Brandt arrived in my life I’d thought of time travel as a means of getting from A to B, where B was some moment in the last half century. The Vauxhall Dynasty was designed for ease of use and for comfort: 1,241 years on the clock, plenty of boot space and a good enough engine. A family car left over from when I had a family. I was Professor of Political History at the University of Birmingham, forty-five years old, and fully cognisant of time’s measure.

I first became aware of Brandt through her vehicle, a sleek low-slung monster with orange bodywork and chrome fins. The chrononic engine was fully exposed, thrusting through the bonnet in a twin set of metal pipes that looked like the lower jaw of a robot shark. It was parked in the space next to mine in the university car park, and my door chipped a spot of paint from it as I got out. I was worried about this until I saw that the impressive time machine, up close, was actually covered in a whole series of scratches and dents. This effect of injured perfection was mirrored in the face and hands and clothes of Brandt when I was later introduced to her by the principal at a wine and canapés gathering in the staffroom. Brandt was an artist of some repute. She made only a passing gesture towards me at the welcoming party, with a few words of non-committed intent. But I saw the scratches on her otherwise clear skin, one on her brow and the other near the left eye, and the tiny rips in her floor-length dress, the oil patches on her denim jacket. Retreating to the buffet table, I studied her discreetly. She was my age or thereabouts, but I couldn’t help feeling that she possessed arcane knowledge of some kind, perhaps of the nation’s impending doom. Ridiculous, of course: we could travel a few days into the future, no more. I learned from Mark Travis of the Sociology department that Brandt was unmarried, and was a fully paid-up member of the couldn’t-give-a-damn set, whatever that might mean. His voice took on a peevish tone: perhaps he was jealous. Travis was our self-styled resident rebel, and the arrival of Brandt, even if only for a week of lectures and masterclasses, had knocked him off his perch.

There was a moment when I caught Alexa Brandt’s gaze across the room, among the various department heads and senior administrators. The look she gave could not be easily decoded, a sense of vagueness caused by two or more opposing emotions crowding the same face. And then with a shock I realised that in fact I was seeing stray flickers of time around her body, as though even away from her vehicle she was still travelling, if only for a few seconds forward and back, over and over again. And then the illusion, if such it was, ended, and her features returned to a more readable expression: she was smiling at me.

I did not see her again until the next evening, on the occasion of her first lecture. The hall was filled with eager students and tutors and even a number of journalists. She was introduced by the Head of Fine Art, Nadia Singh, who called the guest speaker, “The founder of the Meta-Historical movement, and one of the world’s leading performance artists.” I felt my insides clench at the dreaded phrase. I had had to sit through too many student “Performance Art” events, at Nadia’s request: all those earnest young men and women intent on punishing society by punishing their own bodies, or vice versa. So I was not, in all honesty, expecting much.

The lecture hall darkened and a series of moving images appeared on the large screen above the podium. It showed ranks of police officers, some of them on horseback, clashing with members of the public in a field. The police held riot shields in front of them, as they pressed forward, only to be met with a hail of stones. The situation quickly descended into a full-scale riot. One man was attacked viciously with a truncheon.

Brandt’s voice sounded light and assured as she spoke from the lectern. “On the eighteenth of June in 1984, a national coal miner’s strike in Britain came to a head when five thousand pickets faced six thousand police officers in a field in South Yorkshire. This event became known as the Battle of Orgreave. Here, in footage taken by a BBC camera crew, we see the climactic moment of the battle, as the mounted police officers charge against the massed strikers, breaking their ranks.”

Most of the students in attendance had not been born at the time of the strike, and probably had little or no knowledge at all of the clash at Orgreave. I was seven years old in 1984, a witness to the events as something seen only in passing on a television screen. But two years ago I had taken my second-year tutorial group on a field trip to the event, using the university’s minibus to take us there, a somewhat rundown time-machine which barely got us there and back in one piece. Brandt had taken a similar trip, as she now explained.

“A few weeks ago I travelled thirty-nine years back in time, to the battle, with a small crew of my own. Here is what we filmed.”

The rioters vanished from the screen to be replaced by the same field, but empty now, all the people invisible, removed from our sight and hearing. I brought to mind Professor John Henwick’s famous cry of despair when he returned from the world’s very first time trip: “The past is empty! There’s nobody there!” The field at Orgreave, as shown on the screen, was simply that: a field. Or at least appeared to be so, to the camera’s lens and the human eye. But as always with any crowded, historically important, or emotionally charged event, the air was saturated with a kind of magical energy, a series of random blurs and shudders, a bleed-through from society’s collective memories of the event, and its media record.

Alexa Brandt appeared on the screen, stepping into the empty field’s centre. An actor on an empty stage. She faced the camera, staring ahead for a few seconds. Then she took off her jacket and started to unbutton her shirt. It took only a moment to realise what she was doing: she was getting undressed. I knew that nudity was a standard part of any performance artist’s repertoire of effects, usually presented in such a way as to remove every last speck of eroticism. Of course, no matter how we humans try, the animal instinct can never be completely shut away: the id does not have a lock and key. The audience responded to the display with the usual mix of embarrassment and gasps. However, just before her filmed body might become fully exposed, Brandt clicked her remote control once more, this time to superimpose the original footage of the battle onto the empty field. And now, within this prime display of aggressive male behaviour, a lone naked female figure stood, seen now and then as the miners and policemen surged back and forth in a great clash of fists and clubs. The police horses whinnied and neighed. This uneasy juxtaposition of exposed flesh and political violence had a profound effect. The audience fell into silence. I squirmed in my seat. My disquiet was increased by the thought that the past struggles of the working classes for dignity and a living wage were now being turned into an art event for our pleasure and contemplation.

Somebody coughed and that seemed to break the atmosphere. The lecture hall’s screen faded to darkness. Brandt waited a moment before she spoke.

“Because of the fifty-three-year limit on our travels into the past, events such as the Battle of Orgreave will one day be out of bounds. We will have to transfer our desperate needs to other, more recent happenings. Of course, there are many to choose from.” She named a few of the major disasters and calamities of recent decades. “Thrills galore. But they too, in turn, will be eaten up, removed from our scope. So then, we have a duty, as occupants of the present, to populate the past with meaning. In other words, let us make our own catastrophes, now, today, so that future travellers will have their own places of pilgrimage.” She paused for effect. “Only time travel gives any true meaning to the past… And to the future.”

It was difficult to know if she was being ironic. Her features gave nothing away, even when she angled her face upwards into the direct beam of the lecture hall’s spotlight. I rubbed at my eyes as her image flickered, very like a stuttering film. I was reminded again of the time in the staff room when her features had blurred. I was beginning to think that Alexa Brandt would never be fixed to one definite period of time.

* * *

Two days later I went on a field trip with my first-year students. The minibus delivered us to the empty Pallasades shopping centre of 2011, the starting point for the Birmingham riots of that year. It seemed Brandt’s lecture had fired up my students’ sense of youthful unrest. We walked along New Street, Bull Street, and Corporation Street, taking photos of the broken windows of mobile phone shops and sporting goods retailers. We examined the burnt-out skeletons of cars and made careful notes of the exact progress of the rioters to the Bull Ring, where a stand-off with the local police force took place. One eager young student threw a stone through a building society’s window, her very own mini-riot. We walked where the rioters had walked as I spouted the necessary theories and drew parallels with the Bull Ring riots of 1839, when the Chartist marchers had campaigned on these same streets for political reform. I tried to instil in the group that sense of the past as being not so much unpopulated, more a system of interlocking energies left behind as we moved on our lonely way through the ever-evolving present moment. I wasn’t having much fun of it, and I wished I could take them as far back as 1839, and show them the effects of a real riot. The sky clouded over. The streets shimmered with a pale violet light. In the window of a ravaged clothing store I saw myself reflected, myself and my students as a band of righteous working-class demonstrators seeking proper representation in Parliament.

A loud noise disturbed my fantasy, the crunch of steel on steel. I turned quickly to see the orange flash of Alexa Brandt’s Vanguard pulling away from the crushed side of a police car. My students gathered around, excited beyond measure by the sudden appearance of the visiting lecturer. The front bumper of her vehicle was torn away as she reversed, but she seemed little undisturbed by this. She waved to us from the driving seat. The Vanguard glowed with the after-effects of the crash, with ribbons of stolen time, as she drove past us at speed, heading for the access road that circled the Bull Ring shopping centre.

I had to imagine she had followed me on purpose into the past. Was this an act of sabotage on her part, to disrupt my teaching practices? Or was there some ulterior motive behind the deliberate crash, a motive I could not yet work out, hidden in the fragments of the shattered windscreen of the police car? I couldn’t help but see the cubes of glass as a broken map.

* * *

Friday was the final day of Brandt’s residency. Her well-attended public masterclass was not so much an exercise in mentoring, more a series of ritualised humiliations for the students. Afterwards we stood together on the roof of the Arts block, drinking gin and tonic from plastic cups. She’d invited me up there to view the satellites of the Temporal Positioning System as they criss-crossed overhead. We tracked the shining trajectories in silence. Then she gestured to the empty quadrangle below. “How sad it is, for the tourist industry, now that the Stones’ concert in Hyde Park has moved beyond our reach. Of course…” She had still not looked at me. “Of course, there might yet be a way to extend the limit, both forward and back. If we could only find a way of breaking through the barrier.”

“Surely Henwick’s Second Law disproves that possibility once and for all.”

She laughed. “You really do need to have an adventure, James. Perhaps we’ll meet again one day. We could watch the world end together.”

Despite her mocking tone, I sensed the seriousness of her nature.

She continued, “Imagine an event intimate but violent enough to steal time from one person, and give it to another. A smashing together of two time zones might do it, for instance, past and present in a head-on collision. If a person could harness that explosion of energy for their own ends, create a propulsive force from it… Well, who knows when or where they might end up?”

The stilled beauty of the night and the cold stars and the silver pathways of the TPS satellites as they threaded time into a patchwork contrasted exquisitely with the ideas being expressed. I felt myself set free suddenly from the lattice of hours, days, and years. I could theorise that Brandt’s closeness had brought this feeling about. Our eyes met. I nodded, hoping for a sign in return.

The back of her hand touched mine, softly.

It was a romantic gesture of a sort; our wristwatches were swapping information.

* * *

I travelled several hours forward into tomorrow. The streets, traffic signs and buildings were turning grey and fuzzy. The road was empty but for a crashed delivery truck lodged against the central reservation barrier. Fragments of chrononic energy floated in a cloud around the scene. Several canisters of chronoplasm had rolled from the truck bed, one of them spilling its contents across the tarmac in a thick, jelly-like oil-slick. There was no sign of the driver. Another of Brandt’s victims, no doubt, thrust back into last week, last month, last year, by the sheer force of the collision. The truck clung onto the present moment for a while longer, but was already losing its form and colour. Soon it would join the driver in the past.

The next off-ramp released me from the motorway’s strictly chronological motion. Brandt’s vehicle was represented by a dot on my TPS display, the symbol of my own vehicle following behind at a distance of a few hours. She was already speeding ahead. I put my foot down and tried at least to keep her signal on the screen. I followed her along the empty streets of Bickerstaffe. What was she looking for in this suburban town? I located her time machine parked outside a four-storey office block. We were far enough into the future now that the bus shelters and shopfronts melted away, no matter how much I concentrated on them. Brandt’s Vanguard was badly dented, decorated with numerous scratches and crumpled above the left front wheel. The windscreen was smeared with streaks of dirt and what might even have been splashes of blood.

The pavement was soft and sticky underfoot. I could walk through the locked glass doors of the office block without opening them: my body passed through the separated molecules of the glass like treacle through a sieve. But I was not used to future travel, nor to being so close to the edge of known time, and I shuddered from the effort.

The lift was resting at the fourth floor, according to the indicator panel above the door. I had the impression that Brandt was leaving clues for me, traces I could follow. But why? I could not work out my exact role in her endeavours. I got out at the top floor and searched the offices. Several of the desks were occupied with people trying to get in a few extra hours of work.

I found Brandt standing alone at a window. I joined her and followed her gaze over the misty buildings already half covered with grey slime. A few streets further on and everything was lost to the future; for now, at least.

“At the age of sixteen I came to work here, as an apprentice. My first job.”

I was surprised. “You didn’t go to art school?”

“No. I had no concept of myself as an artist. But I remember well my first proper trip into the past. My parents took me to the site of the World Cup Final, 1966. Wembley Stadium.”

“The sacred turf?”

“Exactly.” She turned to face me. “I could sense the football players around me as ghosts in the air, even with the crowd of fellow tourists alongside. Hurst, Moore, Banks, Bobby Charlton. The whole team! And I felt I might partake of the glory myself. Why not? Scoring that final goal in the last minute of extra time. Can you imagine?”

She gazed at the limits of the future for a moment.

“All gone now, of course, seeped away into the deep past. Never again to be visited.”

Turning to face the workers at their desks, she said, “Look at those people, desperately seeking some scrap of future knowledge, something to give them an edge in their lives, their careers.” Her anger rose easily. “We have fifty-three years of the past to visit, and a few days of the future, such glorious opportunities… and what do we do with them?”

She didn’t wait for my answer.

“We mine them for resources. Money, power, love, sex, art, films, the sheer overloaded poetry of things out of time collected and recollected, bought and sold along the new trade routes, the slip roads of the chronoverse.”

“And what about you, Alexa? Why are you here?”

“I could have easily stayed in this job. I’d be a branch manager by now, or perhaps working at head office. Marriage, kids. A nice house. Instead…”

She looked at me with such intensity, I could hardly bear it. Her face blurred with tiny half-second delays like a series of masks.

“Alexa, you deliberately gave me your TPS data. You wanted me to accompany you, or at least to follow you.”

“Is that what you think, James?”

“Come back with me, come back to the present day. We can…”

But the words ran out, leaving only a sudden urge to take her in my arms. But something held me back, not least the idea that her lips, and mine, would be too soft, her skin the same. We were too close to the edge of possibility, and our bodies would melt into slime, becoming potential only, without weight or substance. Two objects that had not yet happened, one seeking the other.

And so the moment passed.

She walked by me, heading for the stairwell. I followed her outside, to her car. “Alexa. Don’t do this, where are you going?”

I made an attempt to grab her arm, only to grip at empty space. The bleed-through from her engine’s exhaust infected my sight. My eyes clouded over and the air was filled with the whine of her Estelle Vanguard as it drove away from the kerb, quickly disappearing into the thick grey haze where the street dissolved into a viscous goo.

* * *

We can visit the past, because the past actually happened. It is made from memories. But the future does not yet exist, beyond what we can picture it to be, these few imagined events constructed from the essence of time itself: chronoplasm. Or, as Professor Henwick succinctly put it: The past is an empty film set; the future is a mound of slime.

People only exist in the present.

We only exist in the present moment, only in the present, only in the present. I had to keep repeating the mantra to myself. But out there in the grey zone, the present very quickly blurred over as any possible concept of it came to a faltering end: it lost coherence.

I was soon caught in a maze of slip roads. The interior of the Dynasty was heating up. My fingertips were soft and sticky on the steering wheel. I was driving the idea of what my car might be in the next minute, the next minute, the next minute. Soon I would merge with the vehicle and then disappear into the murk, the events of my future lost in time as we moved beyond the realm of probability and analysis. At least the temporal positioning satellites were still operational, but their signals came through in intermittent bursts, tracing strange routes. This was the Spaghetti Junction of time’s road system, a tangled skein of dead-ends, mirages, and four-dimensional curves. I very quickly lost all hope of finding Brandt; she was already too far ahead of me, unseen.

I slowed the car and turned on the headlamps. The beams showed only the waving form of a steel fence and a raised barrier. The ground was covered in markings. I had entered a car park outside a large modern building. All the signs were fuzzy, but I made out enough letters to know this was the Hawley Freans shopping and leisure centre, some eight miles outside of Bickerstaffe. The structure was barely formed, a looming mass of semi-coagulated materials. Yellow strands of light dripped from the windows and doors like pus from a pattern of sores.

I felt I could go no further. Another few yards forward and my time machine might collapse under me, and my body seep into the tarmac up to my ankles. And so I brought the Dynasty to a halt, allowing the engine to idle. The thick slimy air pressed against my windscreen, bending the glass. I looked at my wristwatch: the hands had melted into the dial. The TPS screen showed only a solid glow, the multifold of possible timeways all present at once, shimmering against each other.

I had failed. It seemed difficult to even put the thought together in my brain, as the synaptic pathways formed into a single clump of paste. This far away from temporal reality, what hope could I have of self-awareness; without before and after, there could be no true concept of now. And yet, despite this, Alexa Brandt sought a state beyond the clock, some realm of fantastical possibility.

Freshly determined to find her, I drove forward a little further. The gelatinous bulk of the shopping centre melted and merged with the air around it as it lost its hold on the world: the future had taken possession of it.

My hands and the steering wheel were now one continuous object.

I fused into the soft warm plastic of the seat.

A grey mist poured out of the heating vents, staining the windscreen.

Not a single thought remained in my mind.

The numbers lifted away from the dashboard clock to drift around the car’s interior, clogging my eyes and ears with their waxy substance.

Zero, zero, zero seconds.

Here was the moment without a moment, out of which two beams of yellow light appeared, and then a flash of orange at the corner of my eye. They seemed to take a full hour to reach me, these two colours, streaking in from some far-off lateral zone, and yet that full hour passed in an instant before contact was made, the colours quickly forming into the headlamps and bonnet of Brandt’s Vanguard.

She was speeding down towards me.

The moment of impact ran through my entire body, casting me free of my flesh. I was floating in space with my vehicle around me offering a jelly-like support system. There was no pain. The world moved along at a leisurely pace… Until the wheels hit the tarmac and the bodywork crunched and the chassis pressed against the engine block with a jolt. The airbag puffed against my chest in a ghost of breath, and passed right through me, bouncing into the distant otherworld of the back seat. The seat belt clasped me in a lover’s soft embrace.

My eyes blossomed with splendour. I was looking into the gaze of Chronos himself, a gaze that quickly turned into the twin-beamed stare of Brandt’s time machine as it revved up and sped forward once more, its tyres snarling on the molten surface of the road. We met head-on, bonnet to bonnet, two liquid vehicles dissolving into each other.

The tarmac bubbled in the heat raised by the collision.

The windscreen flowed like oil.

Brandt appeared in the seat next to me, her hands clasped on her own steering wheel. She grinned. Hours passed as the grin was formed, something a demon might express.

Her machine was passing through mine.

Give me your time, James. As much of it as possible. I need it all.

Her voice sounded like a broadcast on a slow-motion radio.

We were two phantoms drifting through each other, touching every single point that could be touched, one set of atoms occupying another, each sliding across the great divide of the car park wrapped in a bubble of rubber and leatherette. Our lips met as one voice, one breath at the perfected centre of the chronocrash, and then we spun away from each other, our vehicles separating in a slow opposite caress across the car park until I came to a juddering halt against a pile of oily gunk that resembled Salvador Dali’s version of a shelter for shopping trolleys.

Everything slowed into silence.

Little drops of blood crawled away across the dashboard.

Tick tick went the engine, but many miles away.

Tick… tick… tick…

Once more Brandt’s time machine smashed into mine.

The seat clothed me in a plastic suit, the pedals slippered my feet, the steering wheel spun like a prayer wheel. The horn beeped from its new housing in the middle of my forehead. The glass of the windscreen flowed back into place as a pair of sparkle-lenses for my eyes: I could see clearly at last. I could see Brandt’s vehicle speeding away through the slime, cutting a roadway through the globular mass of the shopping centre, heading for the future. Just before the road closed around the Vanguard, I saw a glimpse of a landscape beyond this one. And then my head lolled forward into my chest and a slow darkness settled over the car’s already disappearing interior.

* * *

I wandered the aisles of the Hawley Woods shopping centre. This was the original building on this site, constructed in 1969, a slate-grey pebble-dashed concrete slab with a high-rise block of flats planted next to it. A new dream of leisure and living for a new decade, according to the mural in the entranceway. The date on the newspapers in the WH Smith’s was 12 August 1971. Ten shot dead by British troops in Ballymurphy. All the stores were open, the litter bins half full, the sweet sound of The Pioneers’ ‘Let Your Yeah Be Yeah’ drifted from the doorway of the Apricot Layne boutique on the first-floor walkway.

There was no one in sight, not a single person. I was alone.

I dressed my scrapes and bruises at Boots the Chemist and replaced my torn jacket in John Collier’s Menswear. My image moved from one window to the next. I adjusted my wristwatch to the time shown on the clock in the central plaza. The crash had sent me spiralling into the past, to the far edge of traversable space, as Brandt had moved on further into the future. Here I was, on this nondescript day in a nondescript part of England, a lone diner eating a ham and cheese sandwich in Kay’s Corner Cafe. I was an odd Robinson Crusoe, it had to be said. And yet I felt that others must also be seated with me, perhaps at this very table, the people of 1971. They could not see me, nor I them. I might reach out a hand and touch a fellow shopper, and never know it. The thought made me shiver.

Evening fell. When I tried the doors, they were all closed and locked.

How had this happened?

I slept on a wooden bench in the main walkway and dreamed of Alexa Brandt climbing from her vehicle in some mythical world beyond the chronoplasmic hinterlands.

I woke early the next morning with a bad headache. The doors were unlocked. I could smell fresh polish on the floors. The unseen cleaners had come and gone. I walked out to the car park. My crashed time machine looked out of place among the neat ranks of Ford Cortinas and Hillman Imps. A flicker of movement caught my eye and I turned quickly to see a person, or at least the vague outline of a person, walking towards the entrance doors of Woolworth’s. I followed, but lost sight of them among the fancy goods aisles.

As the days passed, I saw more and more of these people, their bodies solidifying out of the clean air, becoming warmer, closer, darker: shoppers, retail workers, street cleaners, a running child. The longer I remain here, I thought, the more real it becomes; like a person whose eyes adapt to the dark, mine were adapting to the past. Today, a woman turned to look at me, and almost asked me a question, and I almost answered. If I waited long enough, the streets and workplaces would slowly be repopulated, and I might then take my place among this long-lost tribe of 1971.

But other times called to me. I pressed feverishly at the buttons on my watch, clicking from one period to another – 1984, 1999, 2001 – the sites of my lessons during the standard academic year. I remembered that first touch on the roof of the Arts block, when Alexa Brandt had shared her information with mine. Perhaps my wristwatch held a further clue as to her ultimate destination? The hands spun around the dial in aimless wander.

I took an A-Z road atlas of Bickerstaffe and Hawley from a shelf in Spencer’s Bookshop and worked out a route towards the ruins of the castle in the centre of the old town, where Henry VIII had once stayed with Anne Boleyn. More importantly, it was also the site of Edwina Norton’s murder in March 1972, an event which triggered a Reclaim the Night march. A year or so from now that date would float away from the roads of time travel, stranding me in the past forever, trapped beyond the memory gate. But I hoped before then that future students and activists with an interest in the history of past struggles might arrive here. I would cadge a lift with them, back to the present day, to 2023. That at least was my plan. But would they be able to see me? By then, I might have become a part of the past completely, invisible to any visiting eye.

Now I sit here on a bench opposite the castle entrance, repeatedly glancing at my watch like a man probing at a wound. People come and go, less ghostly than ever. A young man sits next to me, smoking a cigarette. We manage a few words of conversation. Dusk falls, the streetlamps come on. I think often of Brandt’s prediction: perhaps we’ll meet again one day. We could watch the end of the world together. As then, as now, every word sparkles under the stars, the constant stars, and I hope one day to follow her course through time into further unknown realms.

THE ASTRONAUT GARDEN

PRESTON GRASSMANN

We turned onto a new road, bound for the northeast edge of the Mojave Desert. It was an arid rain-shadow zone where only a few species of flora marked the terrain – perennial sword-shaped shrubs of yucca; white flowers reaching for the cloudless sky; strange, stunted limbs of Joshua trees, sparse enough to defy their Mormon name. Between them were rings of pale-green creosote, resilient and pervasive, stretching outward across the valley. I couldn’t help but see her as part of that landscape, and that we were passing over the terrain of her dreaming mind.

“We still don’t know how conscious they are,” Akari said, her thin voice consoling.

“Will she be aware?” I asked, trying not to remember that final vision of the astronauts in the desert. It had been replayed in endless loops of media coverage for the last week – an impact site marked by blooms of brightly colored mycelia, their bodies all but subsumed by its growth.

“They seem to be responding to their environment,” Akari said. “But even if they have some awareness, it doesn’t mean they’re fully conscious. Please don’t expect too much…”

I remembered the theory of how ophiocordyceps could hijack an ant’s mind, turning its head into a capsule full of spores. It would crawl up to the highest point of the plant and wait for the wind to blow it away.

“How are they responding?” I asked.

“It’s better that you see it for yourself,” Akari said.

* * *

The single fenced-off road was surrounded by media vans and news drones that circled overhead, their holographic corporate logos a chaotic jumble of neon.

“Just beyond that point is ground zero,” Akari said, pointing at a tunnel ahead of us. “The dome covers a radius of two kilometers from the point of impact.”

A crowd of journalists and newscasters had been gathered against the outer fence. I heard my name shouted out as we passed. I tried to think of the only thing that could ease my mind, no matter how unlikely it was – that she was waiting for my arrival.

We passed through a series of gates and into a heavily guarded area, where the road began to descend into the tunnel.

“We’ll be parking about two hundred meters below the site,” Akari said.

“How close will I be able to get?” I asked, feeling the tunnel surround me, endless images playing out between the sporadic ceiling lights.

Flash: cities, pyramids, cheap motels.

Flash: fragments of art, lines of old poems and novels, her voice soft against my ear.

I couldn’t help but see the walls as something alive, closing in.

“The security tunnels are about ten meters from the impact zone,” Akari said.

Sense memories continued, as if pouring down from the surrounding walls, the light-flicker an externalized REM in her desert dream. Was I having a seizure, hallucinations brought on by stress and grief? For a moment, I felt her there against me, the lilt of her fingers, the tip of her tongue meandering the labyrinth of a lobe. I gripped the edge of the seat and closed my eyes. The rhythm of the lights was like short breaths in the dark, heavy with desire. Is that you?

“Are you OK?” Akari asked.

I nodded, thankful she couldn’t see me that well beneath the tunnel lights.

“I have some pictures I’d like you to see before we go in,” Akari said, turning on an overhead light. “I think it’s important you know how it began.” She opened a file stacked with photos.

I pulled away at first, frightened of how I’d feel. But the photos were too abstract – ciphers against the desert, drawing the eye like the exhibits of a post-modern art museum.

In the first image, their suited bodies were like black sculptures against the desert landscape.

I looked away, staring out of the window of the van, trying to fathom the abstracted geometry of her death.

“This was taken two days later,” Akari said.

Bright blooms of plantlike forms radiated from their bodies, mycelia-like explosions against the desert.

“Three days…”

Another image revealed the ground around them bursting with towering stems, spreading outward into caps and gills, more like exotic flora than fungus.

“Is that her?” I asked, pointing to the nearest one.

Akari looked surprised. “That’s right,” she said. “How did you know?”

“Just a guess,” I said, somehow knowing it was a lie.

* * *

You can imagine it as a division between one universe andanother… Jax had told me once, drawing a line between one part of the sky and the other. She had been trying to explain how a wormhole could be opened to form a gateway to another universe. Watching her eyes light up, I couldn’t help but think of how much I wanted to be at the other end of her gaze – to be the gateway, the stars. I’d leaned in to whisper a quote we both knew, that science was the ultimate pornography, isolating objects or events from their contexts in time and space. And then I tried to give her a reason to stay.

It hadn’t been enough.

A year after her departure, news was received that the explorers had found new worlds, and one of them seemed to have the conditions necessary for life. Jax had been the first to find it, and so she gave it the name AE, ostensibly an acronym for Alpha Erridai.

But somehow, I’d always known it was a reference to our last night together and the quote from the book we both admired – The Atrocity Exhibition.

* * *

We arrived in a vast open space that must’ve been deep below the garden. A team of researchers were waiting in hazmat suits.

After parking, we put on our own suits and joined the others. I couldn’t help but feel that we were passing through a gateway, astronauts voyaging out to another world. As we waited for the elevator, I could hear the others breathing as if asleep. Their movements seemed fractured and unreal, like the fragments of a dream. Then I could feel her again, the sense-memories of her touch. Here I am, here, fingers tracing desire lines across tender flesh, erosions of self. There was no way to tell where the borders were, like spores adrift.

* * *

Through the window, a borderless terrain ran riot, collisions of growth that seemed to scorn the boundaries of the dome. All of it was blurred by a mist of living spores. There was no sign of the astronauts or the desert itself, buried beneath the shifting forms.

“Are you noticing anything… familiar?” Akari said, nodding toward the garden. She was watching me now, her solicitous mood giving way to something colder and more impartial.

What could possibly be familiar about any of this? I almost said. Instead, I just shook my head.

I was vaguely aware of others nearby, the murmur of voices, but the garden loomed, anchoring me somewhere far away. I heard a whisper in my ear: Memories… thrivein the dark, surviving for decades in the deep waters of our minds like shipwrecks on thesea…

Ahead of me, the towering stems reshaped themselves like a garden bloom in time-lapse. My head spun and I fell to the ground. Hands came to lift me, but they were far away, less real than the garden. And so I watched the fungi push against the window, brightly colored gills and stems yearning for the world beyond it.

I’m here.

Images formed, flickering views of familiar shapes – mouths entwined, bodies merging, colliding.

Our bodies.

A hand reached out to grasp at the glass, the ghostly spores drifting over lattices of limb, forming into new shapes. Layers of strata peeled back, until I was certain it was just for me.

Akari and the others held me up, trying to lead me away from the glass, but I fought against them.

It’s you.

A house, slowly taking shape behind her, a walkway down into a garden, the dream-strata of her desert mind. It was the same place where she had pointed to the stars and said, You can imagine it as a division between one universe andanother…

She had never forgotten.

The figure pointed toward me, as if I was the sky full of stars, the gateway to other worlds.

At the touch of her finger, a crack formed in the glass.

From somewhere far away, I heard Akari’s panicked voice, saw the steady pulse of red lights. They formed a rhythm, like short breaths in the dark.

The cracks spread outward, like desire lines deepened by need.

For a moment, I thought of the ant again, forced by ophiocordyceps to climb and fall.

And then the glass shattered.

ROADKILL

TOBY LITT

It was not a deer, of that much I was certain. Maybe a very muscular stag. Yes, that’s it, I remember thinking, as I drove on, just an unusually big stag.

And part of me – the old, cowardly part – still wishes I had left it there, both the thought and whatever prompted it, and continued on to Norwich, and not got involved.

But although it being a stag would explain its tawny colour and breadth, shoulder to shoulder, it would not explain the strange rippling musculature of its back. Even at 77mph, I had noted this curious feature, although perhaps the thing’s ribs and spine had been shattered by the impact. With its last strength, it had crawled ten metres more, then slumped down into a ditch near the treeline. Maybe it had been lying there alongside the northbound lanes of the A11 just south of the Elveden War Memorial, for a few days, and had begun to decompose and lose its proper shape.

This all happened in mid-August, so fairly early on in the whole mess – or perhaps very late on, if you want to look at it another way. The temperature that month was regularly reaching eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit. Anything fleshy would start to rot the moment it was dead, and shattered ribs might explain the regular paired bumps down the dorsal region.

In the end, it wasn’t so much curiosity about the animal itself as a wish to test both my eyesight and my conceit that made me double back at the next roundabout. Had I really seen that much detail in the two seconds the thing had been in view? I doubted it, and doubted myself, and because of this I wanted a definitive answer.

It’s possible, also, that I am deceiving myself in giving this account. I will admit to a feeling of shock the first moment I caught sight of the carcase. That shouldn’t be here, I thought. Whatever it is, it’s in the wrong place – the wrong version of reality.

The drive on and back took exactly six minutes, so it was close to noon when I pulled onto the hard shoulder. I was hungry, so ate an apple from my briefcase before I got out. It was a russet, I remember. A very normal snack for me to eat just moments before my life ceased to be normal.

I left the hazard lights flashing but locked the doors. Then I waited for a gap in the traffic. If you know that stretch, it’s a long, straight dual carriageway. Cars go much faster than 77mph.

I had only been attempting to cross for a few seconds when a black Range Rover slowed down and stopped on the other side. Later I realised that Carolyn couldn’t have seen the thing and decided to pull over. Her car had been decelerating and indicating for some time before it reached its stopping point.

“Hey,” I wanted to shout. “That’s mine.” But she was out the driver’s-side door and then hidden from view only a few moments later. The Range Rover was between me and whatever was going on with her and the dead animal. She had either ignored or hadn’t heard me.

The A11 was busy. I took a slight risk crossing the second pair of lanes and got honked at by a Humvee and a Tesla. I think I saw a V-sign, too – very old-fashioned but very Norwich.

By the time I had rounded the Range Rover and into view of the dark-haired woman, she was standing back from the huge animal – which definitely wasn’t a stag – and taking photographs on her phone.

“Look what it is,” she said, with an accent I later found out was Russian. “It’s a sabre-toothed tiger.”

“No, no,” I said, as I approached, but then I came round to where she was and saw the teeth.

“Can you please take one of me with it?” she asked.

“Sure,” I said.

She gave me her phone and crouched down near the giant head, between the long forelegs with their astonishing claws.

Even though I could smell it, I was afraid the beast wasn’t dead – that it would suddenly stir. I wanted to make sure I was protecting her from it.

“Take many,” she said.

On the screen, Carolyn looked younger than she was, which was thirty-six. I realised she’d put a filter on. As I tapped and retapped the white circle, I saw her expression change – no, that’s not it: I saw her change her expression. To begin with she was smiling, almost laughing, but in each image she became sadder and sadder, until finally she started to weep.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

She looked up, brown eyes glistening. “Did you get me?” she asked.

I handed her the phone. She went through the twenty or so photos twice.

“Just a couple more,” she said.

We resumed our poses, with her continuing from where she left off – broken with grief for this magnificent creature, and reaching around its neck to give it a hug.

I felt embarrassed but also extremely angry. If this trivial woman hadn’t been here, I would have been feeling something quite profound. After all, I was in the presence of a lifeform that had been extinct since the last Ice Age. Because of her vanity, I was missing a moment of transcendence.

She took her phone again, and checked again. “Perfect,” she said. “Carolyn,” she said.

“Oliver,” I said.

“I saw it this morning,” she said, “and had to come back. It wasn’t there at eight-thirty. By nine-fifteen, it had appeared. I was on the school run. Don’t judge me.” She nodded at her large car. This was a Mercedes estate, not a whole lot bigger than mine.

I had to go up and touch the sabre-toothed tiger, just to feel the level of detail. It must be a prop from a film, abandoned for some inexplicable reason. But the rough-haired skin moved easily over the muscle beneath, and I knew this body was not man-made.

After this, I stepped back and stood up. Carolyn took my photo.

“I thought you might want one,” she said. “Kneel down.”

I did what she was asking. I don’t know what expression was on my face. Even when I look at those three photographs now, I don’t know what I’m feeling. Some kind of raw incomprehension, not just of this moment but of the time in which I now lived.

“I’ll send them to you,” Carolyn said. I told her my work email, and it was this that allowed them to track me down.

We stayed another fifteen minutes. The smell seemed to become worse and worse. It wasn’t just rot, it was a strong, masculine musk. A few cars seemed to slow down but none stopped.

Although I wanted some moments alone with the tiger, I began to move off when Carolyn did.

“What have we discovered?” she said.

I looked back.

“Something that shouldn’t be here,” I said, a little helplessly.

* * *

I arrived at the brokerage a little late, at half past two, and was arrested – or taken into protective custody – exactly one hour later.

Carolyn, as I heard from her afterwards, had posted the hugging-crying image on her social media and it immediately drew attention. It did not, as you might expect from later events, go viral. Instead, all her accounts were deleted, within seconds, and then her phone rang.

“Luckily,” she said, “Freddie was collecting Cristal and Royce, because they asked where I was then told me to stay there. I was in Marks & Spencer’s, trying to buy lemon sorbet, when they reached me.”

They were not the police, or MI5 or MI6. They were from the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, but the armed division. She was taken from the freezer section to a black car almost identical to her own.

What she said, later, was that they told her – just as they told me – that she had been in contact with potentially hazardous organic material.

We were held separately, in separate bland facilities, for ten days. I think mine was in Kent, but that’s mainly because of the journey time and the look of the skies. The van they transported me in was without windows. Getting