Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

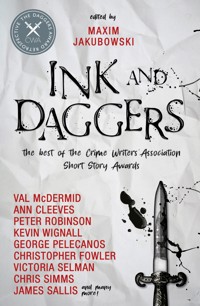

An enthralling anthology of 19 CWA Dagger Award-shortlisted gripping and thrilling stories for the most hardened crime fan. Featuring bestselling authors such as Ann Cleeves, Christopher Fowler and Val McDermid. NINETEEN CWA DAGGER AWARD-WINNING SHORT STORIES FROM THE BEST OF THE BEST IN CRIME FICTION Legendary editor, Maxim Jakubowski, delivers another chilling anthology collecting stories of cold-blooded murder, revenge and crimes-gone-wrong from the best of the best in crime fiction. Spine-chilling and gripping, these tales will grip you with their devious narrators and crafty twists. FEATURING: Ann Cleeves Christopher Fowler Val McDermid Lavie Tidhar Chris Simms Christine Poulson James Sallis Victoria Selman Conrad Williams Stuart Neville George Pelecanos Simon Brett John Lawton Ken Bruen Mickey Spillane & Max Allan Collins Peter Robinson Martyn Waites and Kevin Wignall

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 506

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

by Maxim Jakubowski

THE CONSOLATION BLONDE

by Val McDermid

THE CASE OF DEATH AND HONEY

by Neil Gaiman

THE DEAD THEIR EYES IMPLORE US

by George Pelecanos

HUNTED

by Victoria Selman

EAST OF SUEZ, WEST OF CHARING CROSS ROAD

by John Lawton

MOTHER’S MILK

by Chris Simms

LOVE

by Martyn Waites

RETROSPECTIVE

by Kevin Wignall

BAG MAN

by Lavie Tidhar

THE WASHING

by Christopher Fowler

WEDNESDAY’S CHILD

by Ken Bruen

ACCOUNTING FOR MURDER

by Christine Poulson

ROSENLAUI

by Conrad Williams

METHOD MURDER

by Simon Brett

JUROR 8

by Stuart Neville

A LONG TIME DEAD

by Mickey Spillane & Max Allan Collins

THE PLATER

by Ann Cleeves

WHAT YOU WERE FIGHTING FOR

by James Sallis

THE PRICE OF LOVE

by Peter Robinson

Copyright

About the Editor

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes: A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

Cursed: An Anthology

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dark Detectives: An Anthology of Supernatural Mysteries

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Dead Man’s Hand: An Anthology of the Weird West

Escape Pod: The Science Fiction Anthology

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Out of the Ruins: The Apocalyptic Anthology

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Reports from the Deep End: Stories inspired by J. G. Ballard Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old: Tales with Fresh Bite

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Wonderland: An Anthology

When Things Get Dark

Black is the Night

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

Multiverses: An Anthology of Alternate Realities

Twice Cursed: An Anthology

At Midnight: 15 Beloved Fairy Tales Reimagined

The Other Side of Never: Dark Tales from the World of Peter & Wendy

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Ink and Daggers

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363202

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363219

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © 2023 Maxim Jakubowski. All rights reserved.

The Consolation Blonde © Val McDermid 2003

The Case of Death and Honey © Neil Gaiman 2014

The Dead Their Eyes Implore Us © George Pelecanos 2014

Hunted © Victoria Selman 2020

East of Suez, West of Charing Cross Road © John Lawton 2010

Mother’s Milk © Chris Simms 2008

Love © Martyn Waites 2006

Retrospective © Kevin Wignall 2006

Bag Man © Lavie Tidhar 2018

The Washing © Christopher Fowler 2019

Wednesday’s Child © Ken Bruen 2010

Accounting for Murder © Christine Poulson 2017

Rosenlaui © Conrad Williams 2015

Method Murder © Simon Brett 2012

Juror 8 © Stuart Neville 2014

A Long Time Dead © 2010

Mickey Spillane Publishing, LLC The Plater © Ann Cleeves 2002

What You Were Fighting For © James Sallis 2016

The Price of Love © Peter Robinson 2008

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI

A couple of years ago, it occurred to me that no one had ever collected the wonderful short stories that had over the course of several previous decades won the prestigious Dagger award under one single cover. As I was about to become the Chair of the Crime Writers’ Association, who happen to run the Daggers, the solution was an obvious one and the result was DAGGERS DRAWN, which featured nineteen such past winners; winners all!

It has been a great personal satisfaction that the book, both in the UK and the USA, has been well received both commercially and critically, and brought new attention to some wonderful tales and reminded many a reader of how good a well-crafted crime and mystery short story can prove in the hands of expert writers, both well-known or, in some cases, unjustly forgotten.

So, I have returned to that well of plenty.

Every year, an panel of independent judges, drawn from reviewers, readers, booksellers, academics and other writers, convenes to read what has been published in the UK during the course of the previous calendar year and comes up with a long list, which is then whittled down to a short list and, in due course, a winner. None of the judges can sit for more than three years, so that there is an ever-changing balance of views and opinions. This actually applies to all the categories in which the CWA presents Daggers.

As much as we are proud of all our past winners, there are years – in fact, every single year – when the competition is intense and the choices to be made excruciating and some wonderful books and stories are inevitably not rewarded by a Dagger and remain, for posterity, on the short list. Which does not mean they are inferior in any way. Paradoxically, there are probably more well-known crime writers who have gone no further than the short list than those who actually won the award, which suggested a second volume of stories drawn from the Daggers archives was a must.

Judging what is best between stories (and novels) that sometimes have very little in common beyond their criminous nature is always a subjective choice and depends a lot on the personalities of the judges involved, but I would confidently venture to state that looking back at the Daggers, ever since they were created, the standards have been immaculate and that the CWA has not missed out on any of the big names and books in the field in their choices. And so many authors who were still an unknown quantity when they won a Dagger have gone on to even greater fame since!

So here are a further nineteen outstanding stories, drawn on this occasion from the Short Story Dagger shortlists and I believe they are as dazzling as those I had the privilege to reprint in our first instalment. Again, there were instances when the writer has appeared on the short list on more than one occasion (twice: Peter Lovesey, Ken Bruen, three times: Peter Robinson) in which case I asked them to chose which of their stories they wished to be featured.

Puzzles, dramas, twists, blood, poison, murder, death, whodunits and whydunits: all human life is here as our metaphorical daggers dig deep into the dark side of life.

Savour slowly.

MJ

THE CONSOLATION BLONDE

VAL McDERMID

Awards are meaningless, right? They’re always political, they’re forgotten two days later and they always go to the wrong book, right? Well, that’s what we all say when the prize goes somewhere else. Of course, it’s a different story when it’s our turn to stand at the podium and thank our agents, our partners and our pets. Then, naturally enough, it’s an honor and a thrill.

That’s what I was hoping I’d be doing that October night in New York. I had been nominated for Best Novel in the Speculative Fiction category of the US Book Awards, the national literary prizes that carry not only prestige but also a $50,000 check for the winners. Termagant Fire, the concluding novel in my King’s Infidel trilogy, had broken all records for a fantasy novel. More weeks in the New York Times bestseller list than King, Grisham and Cornwell put together. And the reviews had been breathtaking, referring to Termagant Fire as ‘the first novel since Tolkien to make fantasy respectable.’ Fans and booksellers alike had voted it their book of the year. Serious literary critics had examined the parallels between my fantasy universe and America in the defining epoch of the 60s. Now all I was waiting for was the imprimatur of the judges in the nation’s foremost literary prize.

Not that I was taking it for granted. I know how fickle judges can be, how much they hate being told what to think by the rest of the world. I understood only too well that the succes d’estime the book had enjoyed could be the very factor that would snatch my moment of glory from my grasp. I had already given myself a stiff talking-to in my hotel bathroom mirror, reminding myself of the dangers of hubris. I needed to keep my feet on the ground, and maybe failing to win the golden prize would be the best thing that could happen to me. At least it would be one less thing to have to live up to with the next book.

But on the night, I took it as a good sign that my publisher’s table at the awards dinner was right down at the front of the room, smack bang up against the podium. They never like the winners being seated too far from the stage just in case the applause doesn’t last long enough for them to make it up there ahead of the silence.

My award was third from last in the litany of winners. That meant a long time sitting still and looking interested. But I could only cling on to the fragile conviction that it was all going to be worth it in the end. Eventually, the knowing Virginia drawl of the MC, a middle-ranking news anchorman, got us there. I arranged my face in a suitably bland expression, which I was glad of seconds later when the name he announced was not mine. There followed a short, stunned silence, then, with more eyes on me than on her, the victor weaved her way to the front of the room to a shadow of the applause previous winners had garnered.

I have no idea what graceful acceptance speech she came out with. I couldn’t tell you who won the remaining two categories. All my energy was channeled into not showing the rage and pain churning inside me. No matter how much I told myself I had prepared for this, the reality was horrible.

At the end of the apparently interminable ceremony, I got to my feet like an automaton. My team formed a sort of flying wedge around me; editor ahead of me, publicist to one side, publisher to the other. ‘Let’s get you out of here. We don’t need pity,’ my publisher growled, head down, broad shoulders a challenge to anyone who wanted to offer condolences.

By the time we made it to the bar, we’d acquired a small support crew, ones I had indicated were acceptable by a nod or a word. There was Robert, my first mentor and oldest buddy in the business; Shula, an English sf writer who had become a close friend; Shula’s girlfriend Caroline, and Cassie, the manager of the city’s premier sf and fantasy bookstore. That’s what you need at a time like this, people around who won’t ever hold it against you that you vented your spleen in an unseemly way at the moment when your dream turned to ashes. Fuck nobility. I wanted to break something.

But I didn’t have the appetite for serious drinking, especially when my vanquisher arrived in the same bar with her celebration in tow. I finished my Jack Daniels and pushed off from the enveloping sofa. ‘I’m not much in the mood,’ I said. ‘I think I’ll just head back to my hotel.’

‘You’re at the InterCon, right?’ Cassie asked.

‘Yeah.’

‘I’ll walk with you, I’m going that way.’

‘Don’t you want to join the winning team?’ I asked, jerking my head towards the barks of laughter by the bar.

Cassie put her hand on my arm. ‘You wrote the best book, John. That’s victory enough for me.’

I made my excuses and we walked into a ridiculously balmy New York evening. I wanted snow and ice to match my mood, and said as much to Cassie.

Her laugh was low. ‘The pathetic fallacy,’ she said. ‘You writers just never got over that, did you? Well, John, if you’re going to cling to that notion, you better change your mood to match the weather.’

I snorted. ‘Easier said than done.’

‘Not really,’ said Cassie. ‘Look, we’re almost at the InterCon. Let’s have a drink’

‘OK.’

‘On one condition. We don’t talk about the award, we don’t talk about the asshole who won it, we don’t talk about how wonderful your book is and how it should have been recognized tonight.’

I grinned. ‘Cassie, I’m a writer. If I can’t talk about me, what the hell else does that leave?’

She shrugged and steered me into the lobby. ‘Gardening? Gourmet food? Favorite sexual positions? Music?’

We settled in a corner of the bar, me with Jack on the rocks, she with a Cosmopolitan. We ended up talking about movies, past and present, finding to our surprise that in spite of our affiliation to the sf and fantasy world, what we both actually loved most was film noir. Listening to Cassie talk, watching her push her blonde hair back from her eyes, enjoying the sly smiles that crept out when she said something witty or sardonic, I forgot the slings and arrows and enjoyed myself.

When they announced last call at midnight, I didn’t want it to end. It seemed natural enough to invite her up to my room to continue the conversation. Sure, at the back of my mind was the possibility that it might end with those long legs wrapped around mine, but that really wasn’t the most important thing. What mattered was that Cassie had taken my mind off what ailed me. She had already provided consolation enough, and I wanted it to go on. I didn’t want to be left alone with my rancor and self-pity or any of the other uglinesses that were fighting for space inside me.

She sprawled on the bed. It was that or an armchair which offered little prospect of comfort. I mixed drinks, finding it hard not to imagine sliding those tight black trousers over her hips or running my hands under that black silk tee, or pushing the long shimmering overblouse off her shoulders so I could cover them with kisses.

I took the drinks over and she sat up, crossing her legs in a full lotus and straightening her spine. ‘I thought you were really dignified tonight,’ she said.

‘Didn’t we have a deal? That tonight was off limits?’ I lay on my side, carefully not touching her at any point.

‘That was in the bar. You did well, sticking to it. Think you earned a reward?’

‘What kind of reward?’

‘I give a mean backrub,’ she said, looking at me over the rims of her glasses. ‘And you look tense.’

‘A backrub would be… very acceptable,’ I said.

Cassie unfolded her legs and stood up. ‘OK. I’ll go into the bathroom and give you some privacy to get undressed. Oh, and John – strip right down to the skin. I can’t do your lower back properly if I have to fuck about with waistbands and stuff.’

I couldn’t quite believe how fast things were moving. We hadn’t been in the room ten minutes, and here was Cassie instructing me to strip for her. OK, it wasn’t quite like that sounds, but it was equally a perfectly legitimate description of events. The sort of thing you could say to the guys and they would make a set of assumptions from. If, of course, you were the sort of sad asshole who felt the need to validate himself like that.

I took my clothes off, draping them over the armchair without actually folding them, then lay face down on the bed. I wished I’d spent more of the spring working out than I had writing. But I knew my shoulders were still respectable, my legs strong and hard, even if I was carrying a few more pounds around the waist than I would have liked.

I heard the bathroom door open and Cassie say, ‘You ready, John?’

I was very, very ready. Somehow, it wasn’t entirely a surprise that it wasn’t just the skin of her hands that I felt against mine.

* * *

How did I know it had to be her? I dreamed her hands. Nothing slushy or sentimental; just her honest hands with their strong square fingers, the palms slightly callused from the daily shunting of books from carton to shelf, the play of muscle and skin over blood and bone. I dreamed her hands and woke with tears on my face. That was the day I called Cassie and said I had to see her again.

‘I don’t think so.’ Her voice was cautious, and not, I believed, simply because she was standing behind the counter in the bookstore.

‘Why not? I thought you enjoyed it,’ I said. ‘Did you think it was just a one-night stand?’

‘Why would I imagine it could be more? You’re a married man, you live in Denver, you’re good-looking and successful. Why on earth would I set myself up for a let-down by expecting a repeat performance? John, I am so not in the business of being the Other Woman. A one-night stand is just fine, but I don’t do affairs.’

‘I’m not married.’ It was the first thing I could think of to say. That it was the truth was simply a bonus.

‘What do you mean, you’re not married? It says so on your book jackets. You mention her in interviews.’ Now there was an edge of anger, a ‘don’t fuck with me’ note in her voice.

‘I’ve never been married. I lied about it.’

A long pause. ‘Why would you lie about being married?’ she demanded.

‘Cassie, you’re in the store, right? Look around you. Scope out the women in there. Now, I hate to hurt people’s feelings. Do you see why I might lie about my marital status?’

I could hear the gurgle of laughter swelling and bursting down the telephone line. ‘John, you are a bastard, you know that? A charming bastard, but a bastard nevertheless. You mean that? About never having been married?’

‘There is no moral impediment to you and me fucking each other’s brains out as often as we choose to. Unless, of course, there’s someone lurking at home waiting for you?’ I tried to keep my voice light. I’d been torturing myself with that idea every since our night together. She’d woken me with soft kisses just after five, saying she had to go. By the time we’d said our farewells, it had been nearer six and she’d finally scrambled away from me, saying she had to get home and change before she went in to open the store. It had made sense, but so too did the possibility of her sneaking back in to the cold side of a double bed somewhere down in Chelsea or SoHo.

Now, she calmed my twittering heart. ‘There’s nobody. Hasn’t been for over a year now. I’m free as you, by the sounds of it.’

‘I can be in New York at the weekend,’ I said. ‘Can I stay?’

‘Sure,’ Cassie said, her voice somehow promising much more than a simple word.

* * *

That was the start of something unique in my experience. With Cassie, I found a sense of completeness I’d never known before. I’d always scoffed at terms like ‘soulmate’, but Cassie forced me to eat the words baked in a humble pie. We matched. It was as simple as that. She compensated for my lacks, she allowed me space to demonstrate my strengths. She made me feel like the finest lover who had ever laid hands on her. She was also the first woman I’d ever had a relationship with who miraculously never complained that the writing got in the way. With Cassie, everything was possible and life seemed remarkably straightforward.

She gave me all the space I needed, never minding that my fantasy world sometimes seemed more real to me than what was for dinner. And I did the same for her, I thought. I didn’t dog her steps at the store, turning up for every event like an autograph hunter. I only came along to see writers I would have gone to see anyway; old friends, new kids on the block who were doing interesting work, visiting foreign names. I encouraged her to keep up her girls’ nights out, barely registering when she rolled home in the small hours smelling of smoke and tasting of Triple Sec.

She didn’t mind that I refused to attempt her other love, rock climbing; forty year old knees can’t learn that sort of new trick. But equally, I never expected her to give it up for me, and even though she usually scheduled her overnight climbing trips for when I was out of town on book business, that was her choice rather than my demand. Bless her, she never tried taking advantage of our relationship to nail down better discount deals with my publishers, and I respected her even more for that.

Commuting between Denver and New York lasted all of two months. Then in the same week, I sold my house and my agent sold the King’s Infidel trilogy to Oliver Stone’s company for enough money for me actually to be able to buy a Manhattan apartment that was big enough for both of us and our several thousand books. I loved, and felt loved in return. It was as if I was leading a charmed life.

I should have known better. I am, after all, an adherent of the genre of fiction where pride always, always, always comes before a very nasty fall.

* * *

We’d been living together in the kind of bliss that makes one’s friends gag and one’s enemies weep for almost a year when the accident happened. I know that Freudians claim there is never any such thing as accident, but it’s hard to see how anyone’s subconscious could have felt the world would end up a better or more moral place because of this particular mishap.

My agent was in the middle of a very tricky negotiation with my publisher over my next deal. They were horse-trading and haggling hard over the money on the table, and my agent was naturally copying me in on the emails. One morning, I logged on to find that day’s update had a file attachment with it. ‘Hi, John,’ the e-mail read. ‘You might be interested to see that they’re getting so nitty-gritty about this deal that they’re actually discussing your last year’s touring and miscellaneous expenses. Of course, I wasn’t supposed to see this attachment, but we all know what an idiot Tom is when it comes to electronics. Great editor, cyber-idiot. Anyway, I thought you might find it amusing to see how much they reckon they spent on you. See how it tallies with your recollections...’

I wasn’t much drawn to the idea, but since the attachment was there, I thought I might as well take a look. It never hurts to get a little righteous indignation going about how much hotels end up billing for a one-night stay. It’s the supplementaries that are the killers. $15 for a bottle of water was the best I came across on last year’s tour. Needless to say, I stuck a glass under the tap. Even when it’s someone else’s dime, I hate to encourage the robber barons who masquerade as hoteliers.

I was drifting down through the list when I ran into something out of the basic rhythm of hotels, taxis, air fares, author escorts. Consolation Blonde, $500, I read.

I knew what the words meant, but I didn’t understand their linkage. Especially not on my expense list. If I’d spent it, you’d think I’d know what it was.

Then I saw the date.

My stomach did a back flip. Some dates you never forget. Like the US Book Awards dinner.

I didn’t want to believe it, but I had to be certain. I called Shula’s girlfriend Caroline, herself an editor of mystery fiction in one of the big London houses. Once we’d got the small talk out of the way, I cut to the chase. ‘Caroline, have you ever heard the term “consolation blonde” in publishing circles?’

‘Where did you hear that, John?’ she asked, answering the question inadvertently.

‘I overheard it in one of those chi-chi midtown bars where literary publishers hang out. I was waiting to meet my agent, and I heard one guy say to the other, “He was OK after the consolation blonde.” I wasn’t sure what it meant but I thought it sounded like a great title for a short story.’

Caroline gave that well-bred middle-class Englishwoman’s giggle. ‘I suppose you could be right. What can I say here, John? This really is one of publishing’s tackier areas. Basically, it’s what you lay on for an author who’s having a bad time. Maybe they didn’t win an award they thought was in the bag, maybe their book has bombed, maybe they’re having a really bad tour. So you lay on a girl, a nice girl. A fan, a groupie, a publicity girlie, bookseller, whatever. Somebody on the fringes, not a hooker as such. Tell them how nice it would be for poor old what’s-his-name to have a good time. So the sad boy gets the consolation blonde and the consolation blonde gets a nice boost to her bank account plus the bonus of being able to boast about shagging a name. Even if it’s a name that nobody else in the pub has ever heard before.’

I felt I’d lost the power of speech. I mumbled something and managed to end the call without screaming my anguish at Caroline. In the background, I could hear Bob Dylan singing Idiot Wind. Cassie had set the CD playing on repeat before she’d left for work and now the words mocked me for the idiot I was.

Cassie was my Consolation Blonde.

I wondered how many other disappointed men had been lifted up by the power of her fingers and made to feel strong again? I wondered whether she’d have stuck around for more than that one-night stand if I’d been a poor man. I wondered how many times she’d slid into bed with me after a night out, not with the girls, but wearing the mantle of the Consolation Blonde. I wondered whether pity was still the primary emotion that moved her when she moaned and arched her spine for me.

I wanted to break something. And this time, I wasn’t going to be diverted.

* * *

I’ve made a lot of money for my publisher over the years. So when I show up to see my editor, Tom, without an appointment, he makes space and time for me.

That day, I could tell inside a minute that he wished for once he’d made an exception. He looked like he wasn’t sure whether he should just cut out the middle man and throw himself out of the twenty-third floor window. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he yelped in response to my single phrase.

‘Bullshit,’ I yelled. ‘You hired Cassie to be my consolation blonde. There’s no point in denying it, I’ve seen the paperwork.’

‘You’re mistaken, John,’ Tom said desperately, his alarmed chipmunk eyes widening in dilemma.

‘No. Cassie was my consolation blonde for the US Book Awards. You didn’t know I was going to lose, so you must have set her up in advance, as a stand-by. Which means you must have used her before.’

‘I swear, John, I swear to God, I don’t know…’ Whatever Tom was going to say got cut off by me grabbing his stupid preppie tie and yanking him out of his chair.

‘Tell me the truth,’ I growled, dragging him towards the window. ‘It’s not like it can be worse than I’ve imagined. How many of my friends has she fucked? How many five hundred buck one-night stands have you pimped for my girlfriend since we got together? How many times have you and your buddies laughed behind my back because the woman I love is playing consolation blonde to somebody else? Tell me, Tom. Tell me the truth before I throw you out of this fucking window. Because I don’t have any more to lose.’

‘It’s not like that,’ he gibbered. I smelled piss and felt a warm dampness against my knee. His humiliation was sweet, though it was a poor second to what he’d done to me.

‘Stop lying,’ I screamed. He flinched as my spittle spattered his face. I shook him like a terrier with a rat.

‘OK, OK,’ he sobbed. ‘Yes, Cassie was a consolation blonde. Yes, I hired her last year for you at the awards banquet. But I swear, that was the last time. She wrote me a letter, said after she met you she couldn’t do this again. John, the letter’s in my files. She never cashed the check for being with you. You have to believe me. She fell in love with you that first night and she never did it again.’

The worst of it was, I could tell he wasn’t lying. But still, I hauled him over to the filing cabinets and made him produce his evidence. The letter was everything he’d promised. It was dated the day after our first encounter, two whole days before I called her to ask if I could see her again. Dear Tom, I’m returning your $500 cheque. It’s not appropriate for me to accept it this time. I won’t be available to do close author escort work in future. Meeting John Treadgold has changed things for me. I can’t thank you enough for introducing us. Good luck. Cassie White.

I stood there, reading her words, every one cutting me like the wounds I’d carved into her body the night before.

I guess they don’t have awards ceremonies in prison. Which is probably just as well, given what a bad loser I turned out to be.

THE CASE OF DEATH AND HONEY

NEIL GAIMAN

It was a mystery in those parts for years what had happened to the old white ghost man, the barbarian with his huge shoulder-bag. There were some who supposed him to have been murdered, and, later, they dug up the floor of Old Gao’s little shack high on the hillside, looking for treasure, but they found nothing but ash and fire-blackened tin trays.

This was after Old Gao himself had vanished, you understand, and before his son came back from Lijiang to take over the beehives on the hill.

* * *

This is the problem, wrote Holmes in 1899 : Ennui. And lack of interest. Or rather, it all becomes too easy. When the joy of solving crimes is the challenge, the possibility that you cannot, why then the crimes have something to hold your attention. But when each crime is soluble, and so easily soluble at that, why then there is no point in solving them.

Look: this man has been murdered. Well then, someone murdered him. He was murdered for one or more of a tiny handful of reasons: he inconvenienced someone, or he had something that someone wanted, or he had angered someone. Where is the challenge in that?

I would read in the dailies an account of a crime that had the police baffled, and I would find that I had solved it, in broad strokes if not in detail, before I had finished the article. Crime is too soluble. It dissolves. Why call the police and tell them the answers to their mysteries? I leave it, over and over again, as a challenge for them, as it is no challenge for me.

I am only alive when I perceive a challenge.

* * *

The bees of the misty hills, hills so high that they were sometimes called a mountain, were humming in the pale summer sun as they moved from spring flower to spring flower on the slope. Old Gao listened to them without pleasure. His cousin, in the village across the valley, had many dozens of hives, all of them already filling with honey, even this early in the year; also, the honey was as white as snow-jade. Old Gao did not believe that the white honey tasted any better than the yellow or light-brown honey that his own bees produced, although his bees produced it in meagre quantities, but his cousin could sell his white honey for twice what Old Gao could get for the best honey he had.

On his cousin’s side of the hill, the bees were earnest, hardworking, golden-brown workers, who brought pollen and nectar back to the hives in enormous quantities. Old Gao’s bees were ill-tempered and black, shiny as bullets, who produced as much honey as they needed to get through the winter and only a little more: enough for Old Gao to sell from door to door, to his fellow villagers, one small lump of honeycomb at a time. He would charge more for the brood-comb, filled with bee-larvae, sweet-tasting morsels of protein, when he had brood-comb to sell, which was rarely, for the bees were angry and sullen and everything they did, they did as little as possible, including make more bees, and Old Gao was always aware that each piece of brood-comb he sold were bees he would not have to make honey for him to sell later in the year.

Old Gao was as sullen and as sharp as his bees. He had had a wife once, but she had died in childbirth. The son who had killed her lived for a week, then died himself. There would be nobody to say the funeral rites for Old Gao, no-one to clean his grave for festivals or to put offerings upon it. He would die unremembered, as unremarkable and as unremarked as his bees.

The old white stranger came over the mountains in late spring of that year, as soon as the roads were passable, with a huge brown bag strapped to his shoulders. Old Gao heard about him before he met him.

“There is a barbarian who is looking at bees,” said his cousin.

Old Gao said nothing. He had gone to his cousin to buy a pailful of second rate comb, damaged or uncapped and liable soon to spoil. He bought it cheaply to feed to his own bees, and if he sold some of it in his own village, no-one was any the wiser. The two men were drinking tea in Gao’s cousin’s hut on the hillside. From late spring, when the first honey started to flow, until first frost, Gao’s cousin left his house in the village and went to live in the hut on the hillside, to live and to sleep beside his beehives, for fear of thieves. His wife and his children would take the honeycomb and the bottles of snow-white honey down the hill to sell.

Old Gao was not afraid of thieves. The shiny black bees of Old Gao’s hives would have no mercy on anyone who disturbed them. He slept in his village, unless it was time to collect the honey.

“I will send him to you,” said Gao’s cousin. “Answer his questions, show him your bees and he will pay you.”

“He speaks our tongue?”

“His dialect is atrocious. He said he learned to speak from sailors, and they were mostly Cantonese. But he learns fast, although he is old.”

Old Gao grunted, uninterested in sailors. It was late in the morning, and there was still four hours walking across the valley to his village, in the heat of the day. He finished his tea. His cousin drank finer tea than Old Gao had ever been able to afford.

He reached his hives while it was still light, put the majority of the uncapped honey into his weakest hives. He had eleven hives. His cousin had over a hundred. Old Gao was stung twice doing this, on the back of the hand and the back of the neck. He had been stung over a thousand times in his life. He could not have told you how many times. He barely noticed the stings of other bees, but the stings of his own black bees always hurt, even if they no longer swelled or burned.

The next day a boy came to Old Gao’s house in the village, to tell him that there was someone – and that the someone was a giant foreigner – who was asking for him. Old Gao simply grunted. He walked across the village with the boy at his steady pace, while the boy ran ahead, and soon was lost to sight.

Old Gao found the stranger sitting drinking tea on the porch of the Widow Zhang’s house. Old Gao had known the Widow Zhang’s mother, fifty years, ago. She had been a friend of his wife. Now she was long dead. He did not believe anyone who had known his wife still lived. The Widow Zhang fetched Old Gao tea, introduced him to the elderly barbarian, who had removed his bag and sat beside the small table.

They sipped their tea. The barbarian said, “I wish to see your bees.”

* * *

Mycroft’s death was the end of Empire, and no-one knew it but the two of us. He lay in that pale room, his only covering a thin white sheet, as if he were already becoming a ghost from the popular imagination, and needed only eye-holes in the sheet to finish the impression.

I had imagined that his illness might have wasted him away, but he seemed huger than ever, his fingers swollen into white suet sausages.

I said, “Good evening Mycroft. Doctor Hopkins tells me you have two weeks to live, and stated that I was under no circumstances to inform you of this.”

“The man’s a dunderhead,” said Mycroft, his breath coming in huge wheezes between the words. “I will not make it to Friday.”

“Saturday at least,” I said.

“You always were an optimist. No, Thursday evening and then I shall be nothing more than an exercise in practical geometry for Hopkins and the funeral directors at Snigsby and Malterson, who will have the challenge, given the narrowness of the doors and corridors, of getting my carcass out of this room and out of the building.”

“I had wondered,” I said. “Particularly given the staircase. But they will take out the window-frame and lower you to the street like a grand piano.”

Mycroft snorted at that. Then, “I am forty-nine years old, Sherlock. In my head is the British Government. Not the ballot and hustings nonsense, but the business of the thing. There is no-one else knows what the troop movements in the hills of Afghanistan have to do with the desolate shores of North Wales, no-one else who sees the whole picture. Can you imagine the mess that this lot and their children will make of Indian Independence?”

I had not previously given any thought to the matter. “Will it become independent?”

“Inevitably. In thirty years, at the outside. I have written several recent memoranda on the topic. As I have on so many other subjects. There are memoranda on the Russian Revolution – that’ll be along within the decade I’ll wager – and on the German problem and… oh, so many others. Not that I expect them to be read or understood.” Another wheeze. My brother’s lungs rattled like the windows in an empty house. “You know, if I were to live, the British Empire might last another thousand years, bringing peace and improvement to the world.”

In the past, especially when I was a boy, whenever I heard Mycroft make a grandiose pronouncement like that I would say something to bait him. But not now, not on his deathbed. And also I was certain that he was not speaking of the Empire as it was, a flawed and fallible construct of flawed and fallible people, but of a British Empire that existed only in his head, a glorious force for civilisation and universal prosperity.

I do not, and did not, believe in Empires. But I believed in Mycroft.

Mycroft Holmes. Nine and forty years of age. He had seen in the new century but the Queen would still outlive him by several months. She was more than thirty years older than he was, and in every way a tough old bird. I wondered to myself whether this unfortunate end might have been avoided.

Mycroft said, “You are right of course, Sherlock. Had I forced myself to exercise. Had I lived on birdseed and cabbages instead of porterhouse steak. Had I taken up country dancing along with a wife and a puppy and in all other ways behaved contrary to my nature, I might have bought myself another dozen or so years. But what is that in the scheme of things? Little enough. And sooner or later, I would enter my dotage. No. I am of the opinion that it would take two hundred years to train a functioning Civil Service, let alone a secret service…”

I had said nothing.

The pale room had no decorations on the wall of any kind. None of Mycroft’s citations. No illustrations, photographs or paintings. I compared his austere digs to my own cluttered rooms in Baker Street and I wondered, not for the first time, at Mycroft’s mind. He needed nothing on the outside, for it was all on the inside – everything he had seen, everything he had experienced, everything he had read. He could close his eyes and walk through the National Gallery, or browse the British Museum Reading Room – or, more likely, compare intelligence reports from the edge of the Empire with the price of wool in Wigan and the unemployment statistics in Hove, and then, from this and only this, order a man promoted or a traitor’s quiet death.

Mycroft wheezed enormously, and then he said, “It is a crime, Sherlock.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“A crime. It is a crime, my brother, as heinous and as monstrous as any of the penny dreadful massacres you have investigated. A crime against the world, against nature, against order.”

“I must confess, my dear fellow, that I do not entirely follow you. What is a crime?”

“My death,” said Mycroft, “in the specific. And Death in general.” He looked into my eyes. “I mean it,” he said. “Now isn’t that a crime worth investigating, Sherlock, old fellow? One that might keep your attention for longer than it will take you to establish that the poor fellow who used to conduct the brass band in Hyde Park was murdered by the third cornet using a preparation of strychnine.”

“Arsenic,” I corrected him, almost automatically.

“I think you will find,” wheezed Mycroft, “that the arsenic, while present, had in fact fallen in flakes from the green-painted bandstand itself onto his supper. Symptoms of arsenical poison a complete red-herring. No, it was strychnine that did for the poor fellow.”

Mycroft said no more to me that day or ever. He breathed his last the following Thursday, late in the afternoon, and on the Friday the worthies of Snigsby and Malterson removed the casing from the window of the pale room, and lowered my brother’s remains into the street, like a grand piano.

His funeral service was attended by me, by my friend Watson, by our cousin Harriet and, in accordance with Mycroft’s express wishes – by no-one else. The Civil Service, the Foreign Office, even the Diogenes Club – these institutions and their representatives were absent. Mycroft had been reclusive in life; he was to be equally as reclusive in death. So it was the three of us, and the parson, who had not known my brother, and had no conception that it was the more omniscient arm of the British Government itself that he was consigning to the grave.

Four burly men held fast to the ropes and lowered my brother’s remains to their final resting place, and did, I daresay, their utmost not to curse at the weight of the thing. I tipped each of them half a crown.

Mycroft was dead at forty-nine, and, as they lowered him into his grave, in my imagination I could still hear his clipped, grey, wheeze as he seemed to be saying, “Now there is a crime worth investigating.”

* * *

The stranger’s accent was not too bad, although his vocabulary seemed limited, but he seemed to be talking in the local dialect, or something near to it. He was a fast learner. Old Gao hawked and spat into the dust of the street. He said nothing. He did not wish to take the stranger up the hillside; he did not wish to disturb his bees. In Old Gao’s experience, the less he bothered his bees, the better they did. And if they stung the barbarian, what then?

The stranger’s hair was silver-white, and sparse; his nose, the first barbarian nose that Old Gao had seen, was huge and curved and put Old Gao in mind of the beak of an eagle; his skin was tanned the same colour as Old Gao’s own, and was lined deeply. Old Gao was not certain that he could read a barbarian’s face as he could read the face of a person, but he thought the man seemed most serious and, perhaps, unhappy.

“Why?”

“I study bees. Your brother tells me you have big black bees here. Unusual bees.”

Old Gao shrugged. He did not correct the man on the relationship with his cousin.

The stranger asked Old Gao if he had eaten, and when Gao said that he had not the stranger asked the Widow Zhang to bring them soup and rice and whatever was good that she had in her kitchen, which turned out to be a stew of black tree-fungus and vegetables and tiny transparent river-fish, little bigger than tadpoles. The two men ate in silence. When they had finished eating, the stranger said, “I would be honoured if you would show me your bees.”

Old Gao said nothing, but the stranger paid Widow Zhang well and he put his bag on his back. Then he waited, and, when Old Gao began to walk, the stranger followed him. He carried his bag as if it weighed nothing to him. He was strong for an old man, thought Old Gao, and wondered whether all such barbarians were so strong.

“Where are you from?”

“England,” said the stranger.

Old Gao remembered his father telling him about a war with the English, over trade and over opium, but that was long ago.

They walked up the hillside, that was, perhaps, a mountainside. It was steep, and the hillside was too rocky to be cut into fields. Old Gao tested the stranger’s pace, walking faster than usual, and the stranger kept up with him, with his pack on his back.

The stranger stopped several times, however. He stopped to examine flowers – the small white flowers that bloomed in early spring elsewhere in the valley, but in late spring here on the side of the hill. There was a bee on one of the flowers, and the stranger knelt and observed it. Then he reached into his pocket, produced a large magnifying glass and examined the bee through it, and made notes in a small pocket notebook, in an incomprehensible writing.

Old Gao had never seen a magnifying glass before, and he leaned in to look at the bee, so black and so strong and so very different from the bees elsewhere in that valley.

“One of your bees?”

“Yes,” said Old Gao. “Or one like it.”

“Then we shall let her find her own way home,” said the stranger, and he did not disturb the bee, and he put away the magnifying glass.

* * *

The Croft

East Dene, Sussex

August 11th, 1919

My dear Watson,

I have taken our discussion of this afternoon to heart, considered it carefully, and am prepared to modify my previous opinions.

I am amenable to your publishing your account of the incidents of 1903, specifically of the final case before my retirement, with the following provisions.

In addition to the usual changes that you would make to disguise actual people and places, I would suggest that you replace the entire scenario we encountered (I speak of Professor Presbury’s garden. I shall not write of it further here) with monkey glands, or some such extract from the testes of an ape or lemur, sent by some foreign mystery-man. Perhaps the monkey-extract could have the effect of making Professor Presbury move like an ape – he could be some kind of “creeping man”, perhaps? – or possibly make him able to clamber up the sides of buildings and up trees. Perhaps he could grow a tail, but this might be too fanciful even for you, Watson, although no more fanciful than many of the rococo additions you have made in your histories to otherwise humdrum events in my life and work.

In addition, I have written the following speech, to be delivered by myself, at the end of your narrative. Please make certain that something much like this is there, in which I inveigh against living too long, and the foolish urges that push foolish people to do foolish things to prolong their foolish lives.

There is a very real danger to humanity. If one could live for ever, if youth were simply there for the taking, that the material, the sensual, the worldly would all prolong their worthless lives. The spiritual would not avoid the call to something higher. It would be the survival of the least fit. What sort of cesspool may not our poor world become?

Something along those lines, I fancy, would set my mind at rest.

Let me see the finished article, please, before you submit it to be published.

I remain, old friend, your most obedient servant,Sherlock Holmes

* * *

They reached Old Gao’s bees late in the afternoon. The beehives were grey, wooden boxes piled behind a structure so simple it could barely be called a shack. Four posts, a roof, and hangings of oiled cloth that served to keep out the worst of the spring rains and the summer storms. A small charcoal brazier served for warmth, if you placed a blanket over it and yourself, and to cook upon; a wooden palette in the centre of the structure, with an ancient ceramic pillow, served as a bed on the occasions that Old Gao slept up on the mountainside with the bees, particularly in the autumn, when he harvested most of the honey. There was little enough of it compared to the output of his cousin’s hives, but it was enough that he would sometimes spend two or three days waiting for the comb that he had crushed and stirred into a slurry to drain through the cloth into the buckets and pots that he had carried up the mountainside. Then he would melt the remainder, the sticky wax and bits of pollen and dirt and bee slurry, in a pot, to extract the beeswax, and he would give the sweet water back to the bees. Then he would carry the honey and the wax blocks down the hill to the village to sell.

He showed the barbarian stranger the eleven hives, watched impassively as the stranger put on a veil and opened a hive, examining first the bees, then the contents of a brood box, and finally the queen, through his magnifying glass. He showed no fear, no discomfort: in everything he did the stranger’s movements were gentle and slow, and he was not stung, nor did he crush or hurt a single bee. This impressed Old Gao. He had assumed that barbarians were inscrutable, unreadable, mysterious creatures, but this man seemed overjoyed to have encountered Gao’s bees. His eyes were shining.

Old Gao fired up the brazier, to boil some water. Long before the charcoal was hot, however, the stranger had removed from his bag a contraption of glass and metal. He had filled the upper half of it with water from the stream, lit a flame, and soon a kettleful of water was steaming and bubbling. Then the stranger took two tin mugs from his bag, and some green tea leaves wrapped in paper, and dropped the leaves into the mug, and poured on the water.

It was the finest tea that Old Gao had ever drunk: better by far than his cousin’s tea. They drank it cross-legged on the floor.

“I would like to stay here for the summer, in this house,” said the stranger.

“Here? This is not even a house,” said Old Gao. “Stay down in the village. Widow Zhang has a room.”

“I will stay here,” said the stranger. “Also I would like to rent one of your beehives.”

Old Gao had not laughed in years. There were those in the village who would have thought such a thing impossible. But still, he laughed then, a guffaw of surprise and amusement that seemed to have been jerked out of him.

“I am serious,” said the stranger. He placed four silver coins on the ground between them. Old Gao had not seen where he got them from: three silver Mexican Pesos, a coin that had become popular in China years before, and a large silver yuan. It was as much money as Old Gao might see in a year of selling honey. “For this money,” said the stranger, “I would like someone to bring me food: every three days should suffice.”

Old Gao said nothing. He finished his tea and stood up. He pushed through the oiled cloth to the clearing high on the hillside. He walked over to the eleven hives: each consisted of two brood boxes with one, two, three or, in one case, even four boxes above that. He took the stranger to the hive with four boxes above it, each box filled with frames of comb.

“This hive is yours,” he said.

* * *

They were plant extracts. That was obvious. They worked, in their way, for a limited time, but they were also extremely poisonous. But watching poor Professor Pillsbury during those final days – his skin, his eyes, his gait – had convinced me that he had not been on entirely the wrong path.

I took his case of seeds, of pods, of roots, and of dried extracts and I thought. I pondered. I cogitated. I reflected. It was an intellectual problem, and could be solved, as my old maths tutor had always sought to demonstrate to me, by intellect.

They were plant extracts, and they were lethal.

Methods I used to render them non-lethal rendered them quite ineffective.

It was not a three-pipe problem. I suspect it was something approaching a three-hundred-pipe problem before I hit upon an initial idea – a notion perhaps – of a way of processing the plants that might allow them to be ingested by human beings.

It was not a line of investigation that could easily be followed in Baker Street. So it was, in the autumn of 1903, that I moved to Sussex, and spent the winter reading every book and pamphlet and monograph so far published, I fancy, upon the care and keeping of bees. And so it was that in early April of 1904, armed only with theoretical knowledge, that I took delivery from a local farmer of my first package of bees.

I wonder, sometimes, that Watson did not suspect anything. Then again, Watson’s glorious obtuseness has never ceased to surprise me, and sometimes, indeed, I had relied upon it. Still, he knew what I was like when I had no work to occupy my mind, no case to solve. He knew my lassitude, my black moods when I had no case to occupy me.

So how could he believe that I had truly retired? He knew my methods.

Indeed, Watson was there when I took receipt of my first bees. He watched, from a safe distance, as I poured the bees from the package into the empty, waiting hive, like slow, humming, gentle treacle.

He saw my excitement, and he saw nothing.

And the years passed, and we watched the Empire crumble, we watched the government unable to govern, we watched those poor heroic boys sent to the trenches of Flanders to die, all these things confirmed me in my opinions. I was not doing the right thing. I was doing the only thing.

As my face grew unfamiliar, and my finger-joints swelled and ached (not so much as they might have done, though, which I attributed to the many bee-stings I had received in my first few years as an investigative apiarist) and as Watson, dear, brave, obtuse, Watson, faded with time and paled and shrank, his skin becoming greyer, his moustache becoming the same shade of grey, my resolve to conclude my researches did not diminish. If anything, it increased.

So: my initial hypotheses were tested upon the South Downs, in an apiary of my own devising, each hive modelled upon Langstroth’s. I do believe that I made every mistake that ever a novice beekeeper could or has ever made, and in addition, due to my investigations, an entire hiveful of mistakes that no beekeeper has ever made before, or shall, I trust, ever make again. The Case of the Poisoned Beehive, Watson might have called many of them, although The Mystery of The Transfixed Women’s Institute would have drawn more attention to my researches, had anyone been interested enough to investigate. (As it was, I chided Mrs Telford for simply taking a jar of honey from the shelves here without consulting me, and I ensured that, in the future, she was given several jars for her cooking from the more regular hives, and that honey from the experimental hives was locked away once it had been collected. I do not believe that this ever drew comment.)

I experimented with Dutch Bees, with German Bees and with Italians, with Carniolans and Caucasians. I regretted the loss of our British Bees to blight and, even where they had survived, to interbreeding, although I found and worked with a small hive I purchased and grew up from a frame of brood and a queen cell, from an old Abbey in St. Albans, which seemed to me to be original British breeding stock.

I experimented for the best part of two decades, before I concluded that the bees that I sought, if they existed, were not to be found in England, and would not survive the distances they would need to travel to reach me by international parcel post. I needed to examine bees in India. I needed to travel perhaps further afield than that.

I have a smattering of languages.

I had my flower seeds, and my extracts and tinctures in syrup. I needed nothing more.

I packed them up, arranged for the cottage on the Downs to be cleaned and aired once a week, and for Master Wilkins – to whom I am afraid I had developed the habit of referring, to his obvious distress, as “Young Villikins” – to inspect the beehives, and to harvest and sell surplus honey in Eastbourne market, and to prepare the hives for winter.

I told them I did not know when I should be back.

I am an old man. Perhaps they did not expect me to return.

And, if this was indeed the case, they would, strictly speaking, have been right.

* * *