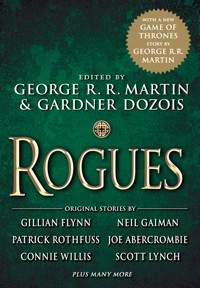

Rogues E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A thrilling collection of twenty-one original stories by an all-star list of contributorsincluding a new A Game of Thrones story by George R. R. Martin! If you're a fan of fiction that is more than just black and white, this latest story collection from #1 New York Times bestselling author George R. R. Martin and award-winning editor Gardner Dozois is filled with subtle shades of gray. Twenty-one all-original stories, by an all-star list of contributors, will delight and astonish you in equal measure with their cunning twists and dazzling reversals. And George R. R. Martin himself offers a brand-new A Game of Thrones tale chronicling one of the biggest rogues in the entire history of Ice and Fire. Follow along with the likes of Gillian Flynn, Joe Abercrombie, Neil Gaiman, Patrick Rothfuss, Scott Lynch, Cherie Priest, Garth Nix, and Connie Willis, as well as other masters of literary sleight-of-hand, in this rogues gallery of stories that will plunder your heartand yet leave you all the richer for it. Featuring all-new stories by Joe Abercrombie, Daniel Abraham, David W. Ball, Paul Cornell, Bradley Denton, Phyllis Eisenstein, Gillian Flynn, Neil Gaiman, Matthew Hughes, Joe R. Lansdale, Scott Lynch, Garth Nix, Cherie Priest, Patrick Rothfuss, Steven Saylor, Michael Swanwick, Lisa Tuttle, Carrie Vaughn, Walter Jon Williams, Connie Willis

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BY GEORGE R. R. MARTIN

A Song of Ice and Fire

Book One: A Game of Thrones

Book Two: A Clash of Kings

Book Three: A Storm of Swords

Book Four: A Feast for Crows

Book Five: A Dance with Dragons

Dying of the Light

Windhaven(with Lisa Tuttle)

Fevre Dream

The Armageddon Rag

Dead Man’s Hand (with John J. Miller)

Short Story Collections

Dreamsongs: Volume I

Dreamsongs: Volume II

A Song for Lya and Other Stories

Songs of Stars and Shadows

Sandkings

Songs the Dead Men Sing

Nightflyers

Tuf Voyaging

Portraits of His Children

Quartet

Edited by George R. R. Martin

New Voices in Science Fiction, Volumes 1–4

The Science Fiction Weight Loss Book(with Isaac Asimov and Martin Harry Greenberg)

The John W. Campbell Awards, Volume 5

Night Visions 3

Wild Cards I–XXII

Co-edited with Gardner Dozois

Warriors I–III

Songs of the Dying Earth

Songs of Love and Death

Down These Strange Streets

Old Mars

Dangerous Women

BY GARDNER DOZOIS

Novels

Strangers

Nightmare Blue(with George Alec Effinger)

Hunter’s Run(with George R. R. Martin and Daniel Abraham)

Short Story Collections

When the Great Days Come

Strange Days: Fabulous Journeys with Gardner Dozois

Geodesic Dreams

Morning Child and Other Stories

Slow Dancing Through Time

The Visible Man

Edited by Gardner Dozois

The Year’s Best Science Fiction #1–30

The New Space Opera(with Jonathan Strahan)

The New Space Opera 2(with Jonathan Strahan)

Modern Classics of Science Fiction

Modern Classics of Fantasy

The Good Old Stuff

The Good New Stuff

The “Magic Tales” series 1–37(with Jack Dann)

Wizards(with Jack Dann)

The Dragon Book(with Jack Dann)

A Day in the Life

Another World

RoguesHardback edition ISBN: 9781783297191Paperback edition ISBN: 9781783297405E-book edition ISBN: 9781783297207

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London, SE1 0UP

First edition August 20141 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © 2014 by George R. R. Martin and Gardner DozoisIntroduction copyright © 2014 by George R. R. MartinIndividual story copyrights appear here

Rogues is a work of fiction. Names, places, and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

This edition published by arrangement with Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.titanbooks.com

Book design by Virginia Norey

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ForJoe and Gay HaldemanTwo Swashbuckling Rogues

Contents

Cover

Also by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction: Everybody Loves a Rogueby George R. R. Martin

TOUGH TIMES ALL OVERby Joe Abercrombie

WHAT DO YOU DO?by Gillian Flynn

THE INN OF THE SEVEN BLESSINGSby Matthew Hughes

BENT TWIGby Joe R. Lansdale

TAWNY PETTICOATSby Michael Swanwick

PROVENANCEby David W. Ball

ROARING TWENTIESby Carrie Vaughn

A YEAR AND A DAY IN OLD THERADANEby Scott Lynch

BAD BRASSby Bradley Denton

HEAVY METALby Cherie Priest

THE MEANING OF LOVEby Daniel Abraham

A BETTER WAY TO DIEby Paul Cornell

ILL SEEN IN TYREby Steven Saylor

A CARGO OF IVORIESby Garth Nix

DIAMONDS FROM TEQUILAby Walter Jon Williams

THE CARAVAN TO NOWHEREby Phyllis Eisenstein

THE CURIOUS AFFAIR OF THE DEAD WIVESby Lisa Tuttle

HOW THE MARQUIS GOT HIS COAT BACKby Neil Gaiman

NOW SHOWINGby Connie Willis

THE LIGHTNING TREEby Patrick Rothfuss

THE ROGUE PRINCE, OR, A KING’S BROTHERby George R. R. Martin

Story Copyrights

About the Editors

Introduction

EVERYBODY LOVES A ROGUEby George R. R. Martin

… though sometimes we live to regret it.

Scoundrels, con men, and scalawags. Ne’er-do-wells, thieves, cheats, and rascals. Bad boys and bad girls. Swindlers, seducers, deceivers, flimflam men, imposters, frauds, fakes, liars, cads, tricksters … they go by many names, and they turn up in stories of all sorts, in every genre under the sun, in myth and legend … and, oh, everywhere in history as well. They are the children of Loki, the brothers of Coyote. Sometimes they are heroes. Sometimes they are villains. More often they are something in between, grey characters … and grey has long been my favorite color. It is so much more interesting than black or white.

I guess I have always been partial to rogues. When I was a boy in the fifties, it sometimes seemed that half of prime-time television was sitcoms, and the other half was Westerns. My father loved Westerns, so growing up, I saw them all, an unending parade of strong-jawed sheriffs and frontier marshals, each more heroic than the last. Marshal Dillon was a rock, Wyatt Earp was brave, courageous, and bold (it said so right in the theme song), and the Lone Ranger, Hopalong Cassidy, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers were heroic, noble, upstanding, the most perfect role models any lad could want … but none of them ever seemed quite real to me. My favorite Western heroes were the two who broke the mold: Paladin, who dressed in black (like a villain) when on the trail and like some sissified dandy when in San Francisco, “kept company” (ahem) with a different pretty woman every week, and hired out his services for money (heroes did not care about money); and the Maverick brothers (especially Bret), charming scoundrels who preferred the gambler’s attire of black suit, string tie, and fancy waistcoat to the traditional marshal’s garb of vest and badge and white hat, and were more likely to be found at a poker table than in a gunfight.

And, you know, when viewed today, Maverick and Have Gun—Will Travel hold up much better than the more traditional Westerns of their time. You can argue that they had better writing, better acting, and better directors than most of the other horse operas in the stable, and you would not be wrong … but I think the rogue factor has something to do with it as well.

But it’s not just fans of old television Westerns who appreciate a good rogue. Truth is, this is a character archetype that cuts across all mediums and genres.

Clint Eastwood became a star by playing characters like Rowdy Yates, Dirty Harry, and the Man With No Name, rogues all. If instead he had been cast as Goody Yates, By-the-Book Billy, and the Man with Two Forms of Identification, no one would ever have heard of him. Now, it’s true, when I was in college I knew a girl who preferred Ashley Wilkes, so noble and self-sacrificing, to that cad Rhett Butler, gambler, blockade-runner … but I think she’s the only one. Every other woman I’ve ever met would take Rhett over Ashley in a hot minute, and let’s not even talk about Frank Kennedy and Charles Wilkes. Harrison Ford comes across rather roguishly in every part he plays, but of course it all started with Han Solo and Indiana Jones. Is there anyone who truly prefers Luke Skywalker to Han Solo? Sure, Han is only in it for the money, he makes that plain right from the start … which makes it all the more thrilling when he returns at the end of Star Wars to put that rocket up Darth Vader’s butt. (Oh, and he DOES shoot first in the cantina scene, no matter how George Lucas retcons that first movie.) And Indy … Indy is the very definition of rogue. Pulling out his gun to shoot that swordsman wasn’t fair at all … but my, didn’t we love him for it?

But it’s not just television and film where rogues rule. Look at the books.

Consider epic fantasy.

Now, fantasy often gets characterized as a genre in which absolute good battles absolute evil, and certainly that sort of thing is plentiful, especially in the hands of the legions of Tolkien imitators with their endless dark lords, evil minions, and square-jawed heroes. But there is an older subgenre of fantasy that absolutely teems with rogues, called sword and sorcery. Conan of Cimmeria is sometimes characterized as a hero, but let us not forget, he was also a thief, a reaver, a pirate, a mercenary, and ultimately a usurper who installed himself on a stolen throne … and slept with every attractive woman he met along the way. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are even more roguish, albeit somewhat less successful. It is unlikely either one will end up a king. And then we have Jack Vance’s thoroughly amoral (and thoroughly delightful) Cugel the Clever, whose scheming never quite seems to produce the desired results, but still …

Historical fiction has its share of dashing, devious, untrustworthy scalawags as well. The Three Musketeers certainly had their roguish qualities. (You cannot really buckle a swash without some.) Rhett Butler was as big a rogue in the novel as he was in the film. Michael Chabon gave us two splendid new rogues in Amram and Zelikman, the stars of his historical novella Gentlemen of the Road, and I for one hope we see a lot more of that pair. And of course there is George MacDonald Fraser’s immortal Harry Flashman (that’s Sir Harry Paget Flashman VC KCB KCIE to you, please), a character kinda sorta borrowed from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Thomas Hughes’s classic British-boarding-school novel (sort of like Harry Potter without quidditch, magic, or girls). If you haven’t read MacDonald’s Flashman books (you can skip the Hughes, unless you’re into Victorian moralizing), you have yet to meet one of literature’s great rogues. I envy you the experience.

Westerns? Hell, the whole Wild West teemed with rogues. The outlaw hero is just as common as the outlaw villain, if not more so. Billy the Kid? Jesse James and his gang? Doc Holliday, rogue dentist extraordinaire? And if we may glance back at television once again—pay cable this time, though—we also have HBO’s fabulous and much-lamented Deadwood, and the dastard at the center of it all, Al Swearengen. As played by Ian McShane, Swearengen completely stole that show from its putative hero, the sheriff. But then, rogues are good at stealing. It’s one of the things that they do best.

What about the romance genre? Hoo. The rogue almost always gets the girl in a romance. These days the rogue IS the girl, oft as not, which can be even cooler. It is always nice to see conventions standing on their heads.

Mystery fiction has entire subgenres about rogues. Private eyes have always had that aspect to them; if they were straight-up, by-the-book, just-the-facts-ma’am sort of guys, they would be cops. They’re not.

I could go on. Literary fiction, gothics, paranormal romance, chick lit, horror, cyberpunk, steampunk, urban fantasy, nurse novels, tragedy, comedy, erotica, thrillers, space opera, horse opera, sports stories, military fiction, ranch romances … every genre and subgenre has its rogues; as often as not they’re the characters most cherished and best remembered.

All those genres are not represented in this anthology, alas … but there is part of me that wishes that they were. Maybe it’s the rogue in me, the part of me that loves to color outside the lines, but the truth is, I don’t have much respect for genre barriers. These days I am best known as a fantasy writer, but Rogues is not meant to be a fantasy anthology … though it does have some good fantasy in it. My co-editor, Gardner Dozois, edited a science-fiction magazine for a couple of decades, but Rogues is not a science-fiction anthology either … though it does feature some SF stories as good as anything you’ll find in the monthly magazines.

Like Warriors and Dangerous Women, our previous crossgenre anthologies, Rogues is meant to cut across all genre lines. Our theme is universal, and Gardner and I both love good stories of all sorts, no matter what time, place, or genre they are set in, so we went out and invited well-known authors from the worlds of mystery, epic fantasy, sword and sorcery, urban fantasy, science fiction, romance, mainstream, mystery (cozy or hard-boiled), thriller, historical, romance, Western, noir, horror … you name it. Not all of them accepted, but many did, and the results are on the pages that follow. Our contributors make up an all-star lineup of award-winning and bestselling writers, representing a dozen different publishers and as many genres. We asked each of them for the same thing—a story about a rogue, full of deft twists, cunning plans, and reversals. No genre limits were imposed upon on any of our writers. Some chose to write in the genre they’re best known for. Some decided to try something different.

In my introduction to Warriors, the first of our crossgenre anthologies, I talked about growing up in Bayonne, New Jersey, in the 1950s, a city without a single bookstore. I bought all my reading material at newsstands and the corner “candy shops,” from wire spinner racks. The paperbacks on those spinner racks were not segregated by genre. Everything was jammed in together, a copy of this, two copies of that. You might find The Brothers Karamazov sandwiched between a nurse novel and the latest Mike Hammer yarn from Mickey Spillane. Dorothy Parker and Dorothy Sayers shared rack space with Ralph Ellison and J. D. Salinger. Max Brand rubbed up against Barbara Cartland. A. E. van Vogt, P. G. Wodehouse, and H. P. Lovecraft were crammed in with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Mysteries, Westerns, gothics, ghost stories, classics of English literature, the latest contemporary “literary” novels, and, of course, SF and fantasy and horror—you could find it all on that spinner rack, and ten thousand others like it.

I liked it that way. I still do. But in the decades since (too many decades, I fear), publishing has changed, chain bookstores have multiplied, the genre barriers have hardened. I think that’s a pity. Books should broaden us, take us to places we have never been and show us things we’ve never seen, expand our horizons and our way of looking at the world. Limiting your reading to a single genre defeats that. It limits us, makes us smaller. It seemed to me, then as now, that there were good stories and bad stories, and that was the only distinction that truly mattered.

We think we have some good ones here. You will find rogues of every size, shape, and color in these pages, with a broad variety of settings, representing a healthy mix of different genres and subgenres. But you won’t know which genres and subgenres until you’ve read them, for Gardner and I, in the tradition of that old wire spinner rack, have mixed them all up. Some of the tales herein were written by your favorite writers, we expect; others are by writers you may never have heard of (yet). It’s our hope that by the time you finish Rogues, a few of the latter may have become the former.

Enjoy the read … but do be careful. Some of the gentlemen and lovely ladies in these pages are not entirely to be trusted.

Joe Abercrombie

Joe Abercrombie is one of the fastest-rising stars in fantasy today, acclaimed by readers and critics alike for his tough, spare, no-nonsense approach to the genre. He’s probably best known for his First Law trilogy, the first novel of which, The Blade Itself, was published in 2006; it was followed in subsequent years by Before They Are Hanged and Last Argument of Kings. He’s also written the stand-alone fantasy novels Best Served Cold and The Heroes. His most recent novel is Red Country. In addition to writing, Abercrombie is also a freelance film editor, and lives and works in London.

In the fast-paced thriller that follows, he takes us deep into the dirty, rank, melodious, and mazelike streets of Sipani, one of the world’s most dangerous cities, for a deadly game of Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?

TOUGH TIMES ALL OVER

Joe Abercrombie

Damn, but she hated Sipani.

The bloody blinding fogs and the bloody slapping water and the bloody universal sickening stink of rot. The bloody parties and masques and revels. Fun, everyone having bloody fun, or at least pretending to. The bloody people were worst of all. Rogues every man, woman, and child. Liars and fools, the lot of them.

Carcolf hated Sipani. Yet here she was again. Who, then, she was forced to wonder, was the fool?

Braying laughter echoed from the mist ahead and she slipped into the shadows of a doorway, one hand tickling the grip of her sword. A good courier trusts no one, and Carcolf was the very best, but in Sipani, she trusted … less than no one.

Another gang of pleasure-seekers blundered from the murk, a man with a mask like a moon pointing at a woman who was so drunk she kept falling over on her high shoes. All of them laughing, one of them flapping his lace cuffs as though there never was a thing so funny as drinking so much you couldn’t stand up. Carcolf rolled her eyes skyward and consoled herself with the thought that behind the masks they were hating it as much as she always did when she tried to have fun.

In the solitude of her doorway, Carcolf winced. Damn, but she needed a holiday. She was becoming a sour ass. Or, indeed, had become one and was getting worse. One of those people who held the entire world in contempt. Was she turning into her bloody father?

“Anything but that,” she muttered.

The moment the revelers tottered off into the night, she ducked from her doorway and pressed on, neither too fast nor too slow, soft bootheels silent on the dewy cobbles, her unexceptional hood drawn down to an inconspicuous degree, the very image of a person with just the average amount to hide. Which, in Sipani, was quite a bit.

Over to the west somewhere, her armored carriage would be speeding down the wide lanes, wheels striking sparks as they clattered over the bridges, stunned bystanders leaping aside, driver’s whip lashing at the foaming flanks of the horses, the dozen hired guards thundering after, streetlamps gleaming upon their dewy armor. Unless the Quarryman’s people had already made their move, of course: the flutter of arrows, the scream of beasts and men, the crash of the wagon leaving the road, the clash of steel, and finally the great padlock blown from the strongbox with blasting powder, the choking smoke wafted aside by eager hands, and the lid flung back to reveal … nothing.

Carcolf allowed herself the smallest smile and patted the lump against her ribs. The item, stitched up safe in the lining of her coat.

She gathered herself, took a couple of steps, and sprang from the canal side, clearing three strides of oily water to the deck of a decaying barge, timbers creaking under her as she rolled and came smoothly up. To go around by the Fintine bridge was quite the detour, not to mention a well-traveled and well-watched way, but this boat was always tied here in the shadows, offering a shortcut. She had made sure of it. Carcolf left as little to chance as possible. In her experience, chance could be a real bastard.

A wizened face peered out from the gloom of the cabin, steam issuing from a battered kettle. “Who the hell are you?”

“Nobody.” Carcolf gave a cheery salute. “Just passing through!” and she hopped from the rocking wood to the stones on the far side of the canal and was away into the mold-smelling mist. Just passing through. Straight to the docks to catch the tide and off on her merry way. Or her sour-assed one, at least. Wherever Carcolf went, she was nobody. Everywhere, always passing through.

Over to the east, that idiot Pombrine would be riding hard in the company of four paid retainers. He hardly looked much like her, what with the moustache and all, but swaddled in that ever-so-conspicuous embroidered cloak of hers, he did well enough for a double. He was a penniless pimp who smugly believed himself to be impersonating her so she could visit a lover, a lady of means who did not want their tryst made public. Carcolf sighed. If only. She consoled herself with the thought of Pombrine’s shock when those bastards Deep and Shallow shot him from his saddle, expressed considerable surprise at the moustache, then rooted through his clothes with increasing frustration, and finally, no doubt, gutted his corpse only to find … nothing.

Carcolf patted that lump once again and pressed on with a spring in her step. Here went she, down the middle course, alone and on foot, along a carefully prepared route of back streets, of narrow ways, of unregarded shortcuts and forgotten stairs, through crumbling palaces and rotting tenements, gates left open by surreptitious arrangement and, later on, a short stretch of sewer that would bring her out right by the docks with an hour or two to spare.

After this job, she really had to take a holiday. She tongued at the inside of her lip, where a small but unreasonably painful ulcer had lately developed. All she did was work. A trip to Adua, maybe? Visit her brother, see her nieces? How old would they be now? Ugh. No. She remembered what a judgmental bitch her sister-in-law was. One of those people who met everything with a sneer. She reminded Carcolf of her father. Probably why her brother had married the bloody woman …

Music was drifting from somewhere as she ducked beneath a flaking archway. A violinist, either tuning up or of execrable quality. Neither would have surprised her. Papers flapped and rustled upon a wall sprouting with moss, ill-printed bills exhorting the faithful citizenry to rise up against the tyranny of the Snake of Talins. Carcolf snorted. Most of Sipani’s citizens were more interested in falling over than rising up, and the rest were anything but faithful.

She twisted about to tug at the seat of her trousers, but it was hopeless. How much do you have to pay for a new suit of clothes before you avoid a chafing seam just in the worst place? She hopped along a narrow way beside a stagnant section of canal, long out of use, gloopy with algae and bobbing rubbish, plucking the offending fabric this way and that to no effect. Damn this fashion for tight trousers! Perhaps it was some kind of cosmic punishment for her paying the tailor with forged coins. But then Carcolf was considerably more moved by the concept of local profit than that of cosmic punishment, and therefore strove to avoid paying for anything wherever possible. It was practically a principle with her, and her father always said that a person should stick to their principles—

Bloody hell, she really was turning into her father.

“Ha!”

A ragged figure sprang from an archway, the faintest glimmer of steel showing. With an instinctive whimper, Carcolf stumbled back, fumbling her coat aside and drawing her own blade, sure that death had found her at last. The Quarryman one step ahead? Or was it Deep and Shallow, or Kurrikan’s hirelings … but no one else showed themselves. Only this one man, swathed in a stained cloak, unkempt hair stuck to pale skin by the damp, a mildewed scarf masking the bottom part of his face, bloodshot eyes round and scared above.

“Stand and deliver!” he boomed, somewhat muffled by the scarf.

Carcolf raised her brows. “Who even says that?”

A slight pause, while the rotten waters slapped the stones beside them. “You’re a woman?” There was an almost apologetic turn to the would-be robber’s voice.

“If I am, will you not rob me?”

“Well … er …” The thief seemed to deflate somewhat, then drew himself up again. “Stand and deliver anyway!”

“Why?” asked Carcolf.

The point of the robber’s sword drifted uncertainly. “Because I have a considerable debt to … that’s none of your business!”

“No, I mean, why not just stab me and strip my corpse of valuables, rather than giving me the warning?”

Another pause. “I suppose … I hope to avoid violence? But I warn you I am entirely prepared for it!”

He was a bloody civilian. A mugger who had blundered upon her. A random encounter. Talk about chance being a bastard! For him, at least. “You, sir,” she said, “are a shitty thief.”

“I, madam, am a gentleman.”

“You, sir, are a dead gentleman.” Carcolf stepped forward, weighing her blade, a stride length of razor steel lent a ruthless gleam from a lamp in a window somewhere above. She could never be bothered to practice, but nonetheless she was far more than passable with a sword. It would take a great deal more than this stick of gutter trash to get the better of her. “I will carve you like—”

The man darted forward with astonishing speed, there was a scrape of steel, and before Carcolf even thought of moving, the sword was twitched from her fingers and skittered across the greasy cobbles to plop into the canal.

“Ah,” she said. That changed things. Plainly her attacker was not the bumpkin he appeared to be, at least when it came to swordplay. She should have known. Nothing in Sipani is ever quite as it appears.

“Hand over the money,” he said.

“Delighted.” Carcolf plucked out her purse and tossed it against the wall, hoping to slip past while he was distracted. Alas, he pricked it from the air with impressive dexterity and whisked his sword point back to prevent her escape. It tapped gently at the lump in her coat.

“What have you got … just there?”

From bad to much, much worse. “Nothing, nothing at all.” Carcolf attempted to pass it off with a false chuckle, but that ship had sailed and she, sadly, was not aboard, any more than she was aboard the damn ship still rocking at the wharf for the voyage to Thond. She steered the glinting point away with one finger. “Now I have an extremely pressing engagement, so if—” There was a faint hiss as the sword slit her coat open.

Carcolf blinked. “Ow.” There was a burning pain down her ribs. The sword had slit her open too. “Ow!” She subsided to her knees, deeply aggrieved, blood oozing between her fingers as she clutched them to her side.

“Oh … oh no. Sorry. I really … really didn’t mean to cut you. Just wanted, you know …”

“Ow.” The item, now slightly smeared with Carcolf’s blood, dropped from the gashed pocket and tumbled across the cobbles. A slender package perhaps a foot long, wrapped in stained leather.

“I need a surgeon,” gasped Carcolf, in her best I-am-a-helpless-woman voice. The Grand Duchess had always accused her of being overdramatic, but if you can’t be dramatic at a time like that, when can you? It was likely she really did need a surgeon, after all, and there was a chance that the robber would lean down to help her and she could stab the bastard in the face with her knife. “Please, I beg you!”

He loitered, eyes wide, the whole thing plainly gone further than he had intended. But he edged closer only to reach for the package, the glinting point of his sword still leveled at her.

A different and even more desperate tack, then. She strove to keep the panic out of her voice. “Look, take the money, I wish you joy of it.” Carcolf did not, in fact, wish him joy, she wished him rotten in his grave. “But we will both be far better off if you leave that package!”

His hand hovered. “Why, what’s in it?”

“I don’t know. I’m under orders not to open it!”

“Orders from who?”

Carcolf winced. “I don’t know that either, but—”

* * *

Kurtis took the packet. Of course he did. He was an idiot, but not so much of an idiot as that. He snatched up the packet and ran. Of course he ran. When didn’t he?

He tore down the alleyway, heart in mouth, jumped a burst barrel, caught his foot and went sprawling, almost impaled himself on his own drawn sword, slithered on his face through a slick of rubbish, scooping a mouthful of something faintly sweet and staggering up, spitting and cursing, snatching a scared glance over his shoulder—

There was no sign of pursuit. Only the mist, the endless mist, whipping and curling like a thing alive.

He slipped the packet, now somewhat slimy, into his ragged cloak and limped on, clutching at his bruised buttock and still struggling to spit that rotten-sweet taste from his mouth. Not that it was any worse than his breakfast had been. Better, if anything. You know a man by his breakfast, his fencing master always used to tell him.

He pulled up his damp hood with its faint smell of onions and despair, plucked the purse from his sword, and slid blade back into sheath as he slipped from the alley and insinuated himself among the crowds, that faint snap of hilt meeting clasp bringing back so many memories. Of training and tournaments, of bright futures and the adulation of the crowds. Fencing, my boy, that’s the way to advance! Such knowledgeable audiences in Styria, they love their swordsmen there, you’ll make a fortune! Better times, when he had not dressed in rags, or been thankful for the butcher’s leftovers, or robbed people for a living. He grimaced. Robbed women. If you could call it a living. He stole another furtive glance over his shoulder. Could he have killed her? His skin prickled with horror. Just a scratch. Just a scratch, surely? But he had seen blood. Please, let it have been a scratch! He rubbed his face as though he could rub the memory away, but it was stuck fast. One by one, things he had never imagined, then told himself he would never do, then that he would never do again, had become his daily routine.

He checked once more that he wasn’t followed, then slipped from the street and across the rotting courtyard, the faded faces of yesterday’s heroes peering down at him from the newsbills. Up the piss-smelling stairway and around the dead plant. Out with his key, and he wrestled with the sticky lock.

“Damn it, fuck it, shit it—Gah!” The door came suddenly open and he blundered into the room, nearly fell again, turned and pushed it shut, and stood a moment in the smelly darkness, breathing hard.

Who would now believe he’d once fenced with the king? He’d lost. Of course he had. Lost everything, hadn’t he? He’d lost two touches to nothing and been personally insulted while he lay in the dust but, still, he’d measured steels with His August Majesty. This very steel, he realized, as he set it against the wall beside the door. Notched, and tarnished, and even slightly bent toward the tip. The last twenty years had been almost as unkind to his sword as they had been to him. But perhaps today marked the turn in his fortunes.

He whipped his cloak off and tossed it into a corner, took out the packet to unwrap it and see what he had come by. He fumbled with the lamp in the darkness and finally produced some light, almost wincing as his miserable rooms came into view. The cracked glazing, the blistering plaster speckled with damp, the burst mattress spilling foul straw where he slept, the few sticks of warped furniture—

There was a man sitting in the only chair, at the only table. A big man in a big coat, skull shaved to greying stubble. He took a slow breath through his blunt nose and let a pair of dice tumble from his fist and across the stained tabletop.

“Six and two,” he said. “Eight.”

“Who the hell are you?” Kurtis’s voice was squeaky with shock.

“The Quarryman sent me.” He let the dice roll again. “Six and five.”

“Does that mean I lose?” Kurtis glanced over toward his sword, trying and failing to seem nonchalant, wondering how fast he could get to it, draw it, strike—

“You lost already,” said the big man, gently collecting the dice with the side of his hand. He finally looked up. His eyes were flat as those of a dead fish. Like the fishes on the stalls at the market. Dead and dark and sadly glistening. “Do you want to know what happens if you go for that sword?”

Kurtis wasn’t a brave man. He never had been. It had taken all his courage to work up to surprising someone else; being surprised himself had knocked the fight right out of him. “No,” he muttered, his shoulders sagging.

“Toss me that package,” said the big man, and Kurtis did so. “And the purse.”

It was as if all resistance had drained away. Kurtis had not the strength to attempt a ruse. He scarcely had the strength to stand. He tossed the stolen purse onto the table, and the big man worked it open with his fingertips and peered inside.

Kurtis gave a helpless, floppy motion of his hands. “I have nothing else worth taking.”

“I know,” the man said, as he stood. “I have checked.” He stepped around the table and Kurtis cringed away, steadying himself against his cupboard. A cupboard containing nothing but cobwebs, as it went.

“Is the debt paid?” he asked in a very small voice.

“Do you think the debt is paid?”

They stood looking at one another. Kurtis swallowed. “When will the debt be paid?”

The big man shrugged his shoulders, which were almost one with his head. “When do you think the debt will be paid?”

Kurtis swallowed again, and he found his lip was trembling. “When the Quarryman says so?”

The big man raised one heavy brow a fraction, the hairless sliver of a scar through it. “Have you any questions … to which you do not know the answers?”

Kurtis dropped to his knees, his hands clasped, the big man’s face faintly swimming through the tears in his aching eyes. He did not care about the shame of it. The Quarryman had taken the last of his pride many visits before. “Just leave me something,” he whispered. “Just … something.”

The man stared back at him with his dead fish eyes. “Why?”

* * *

Friendly took the sword too, but there was nothing else of value. “I will come back next week,” he said.

It had not been meant as a threat, merely a statement of fact, and an obvious one at that, since it had always been the arrangement, but Kurtis dan Broya’s head slowly dropped, and he began to shudder with sobs.

Friendly considered whether to try and comfort him but decided not to. He was often misinterpreted.

“You should, perhaps, not have borrowed the money.” Then he left.

It always surprised him that people did not do the sums when they took a loan. Proportions, and time, and the action of interest, it was not so very difficult to fathom. But perhaps they were prone always to overestimate their income, to poison themselves by looking on the bright side. Happy chances would occur, and things would improve, and everything would turn out well, because they were special. Friendly had no illusions. He knew he was but one unexceptional cog in the elaborate workings of life. To him, facts were facts.

He walked, counting off the paces to the Quarryman’s place. One hundred and five, one hundred and four, one hundred and three …

Strange how small the city was when you measured it out. All those people, and all their desires, and scores, and debts, packed into this narrow stretch of reclaimed swamp. By Friendly’s reckoning, the swamp was well on the way to taking large sections of it back. He wondered if the world would be better when it did.

… seventy-six, seventy-five, seventy-four …

Friendly had picked up a shadow. Pickpocket, maybe. He took a careless look at a stall by the way and caught her out of the corner of his eye. A girl with dark hair gathered into a cap and a jacket too big for her. Hardly more than a child. Friendly took a few steps down a narrow snicket and turned, blocking the way, pushing back his coat to show the grips of four of his six weapons. His shadow rounded the corner, and he looked at her. Just looked. She first froze, then swallowed, then turned one way, then the other, then backed off and lost herself in the crowds. So that was the end of that episode.

… thirty-one, thirty, twenty-nine …

Sipani, and most especially its moist and fragrant Old Quarter, was full of thieves. They were a constant annoyance, like midges in summer. Also muggers, robbers, burglars, cutpurses, cutthroats, thugs, murderers, strong-arm men, spivs, swindlers, gamblers, bookies, moneylenders, rakes, beggars, tricksters, pimps, pawnshop owners, crooked merchants, not to mention accountants and lawyers. Lawyers were the worst of the crowd, as far as Friendly was concerned. Sometimes it seemed that no one in Sipani made anything, exactly. They all seemed to be working their hardest to rip it from someone else.

But then, Friendly supposed he was no better.

… four, three, two, one, and down the twelve steps, past the three guards, and through the double doors into the Quarryman’s place.

It was hazy with smoke inside, confusing with the light of colored lamps, hot with breath and chafing skin, thick with the babble of hushed conversation, of secrets traded, reputations ruined, confidences betrayed. It was as all such places always are.

Two Northmen were wedged behind a table in the corner. One, with sharp teeth and long, lank hair, had tipped his chair all the way back and was slumped in it, smoking. The other had a bottle in one hand and a tiny book in the other, staring at it with brow well furrowed.

Most of the patrons Friendly knew by sight. Regulars. Some came to drink. Some to eat. Most of them fixed on the games of chance. The clatter of dice, the twitch and flap of the playing cards, the eyes of the hopeless glittering as the lucky wheel spun.

The games were not really the Quarryman’s business, but the games made debts, and debts were the Quarryman’s business. Up the twenty-three steps to the raised area, the guard with the tattoo on his face waving Friendly past.

Three of the other collectors were seated there, sharing a bottle. The smallest grinned at him and nodded, perhaps trying to plant the seeds of an alliance. The biggest puffed himself up and bristled, sensing competition. Friendly ignored them equally. He had long ago given up trying even to understand the unsolvable mathematics of human relationships, let alone to participate. Should that man do more than bristle, Friendly’s cleaver would speak for him. That was a voice that cut short even the most tedious of arguments.

Mistress Borfero was a fleshy woman with dark curls spilling from beneath a purple cap, small eyeglasses that made her eyes seem large, and a smell about her of lamp oil. She haunted the anteroom before the Quarryman’s office at a low desk stacked with ledgers. On Friendly’s first day, she had gestured toward the ornate door behind her and said, “I am the Quarryman’s right hand. He is never to be disturbed. Never. You speak to me.”

Friendly, of course, knew as soon as he saw her mastery of the numbers in those books that there was no one in the office and that Borfero was the Quarryman, but she seemed so pleased with the deception that he was happy to play along. Friendly had never liked to rock boats unnecessarily. That’s how people end up drowned. Besides, it somehow helped to imagine that the orders came from somewhere else, somewhere unknowable and irresistible. It was nice to have an attic in which to stack the blame. Friendly looked at the door of the Quarryman’s office, wondering if there was an office, or if it opened on blank stones.

“What was today’s take?” she asked, flipping open a ledger and dipping her pen. Straight to business without so much as a how do you do. He greatly liked and admired that about her, though he would never have said so. His compliments had a way of causing offense.

Friendly slipped the coins out in stacks, then let them drop, one by one, in rattling rows by debtor and denomination. Mostly base metals, leavened with a sprinkling of silver.

Borfero sat forward, wrinkling her nose and pushing her eyeglasses up onto her forehead, eyes seeming now extra small without them.

“A sword, as well,” said Friendly, leaning it up against the side of the desk.

“A disappointing harvest,” she murmured.

“The soil is stony hereabouts.”

“Too true.” She dropped the eyeglasses back and started to scratch orderly figures in her ledger. “Tough times all over.” She often said that. As though it stood as explanation and excuse for anything and everything.

“Kurtis dan Broya asked me when the debt would be paid.”

She peered up, surprised by the question. “When the Quarryman says it’s paid.”

“That’s what I told him.”

“Good.”

“You asked me to be on the lookout for … a package.” Friendly placed it on the desk before her. “Broya had it.”

It did not seem so very important. It was less than a foot long, wrapped in very ancient stained and balding animal skin, and with a letter, or perhaps a number, burned into it with a brand. But not a number that Friendly recognized.

* * *

Mistress Borfero snatched up the package, then immediately cursed herself for seeming too eager. She knew no one could be trusted in this business. That brought a rush of questions to her mind. Suspicions. How could that worthless Broya possibly have come by it? Was this some ruse? Was Friendly a plant of the Gurkish? Or perhaps of Carcolf’s? A double bluff? There was no end to the webs that smug bitch spun. A triple bluff? But where was the angle? Where the advantage?

A quadruple bluff?

Friendly’s face betrayed no trace of greed, no trace of ambition, no trace of anything. He was without doubt a strange fellow but came highly recommended. He seemed all business, and she liked that in a man, though she would never have said so. A manager must maintain a certain detachment.

Sometimes things are just what they seem. Borfero had seen strange chances enough in her life.

“This could be it,” she mused, though, in fact, she was immediately sure. She was not a woman to waste time on possibilities.

Friendly nodded.

“You have done well,” she said.

He nodded again.

“The Quarryman will want you to have a bonus.” Be generous with your own people, she had always said, or others will be.

But generosity brought no response from Friendly.

“A woman, perhaps?”

He looked a little pained by that suggestion. “No.”

“A man?”

And that one. “No.”

“Husk? A bottle of—”

“No.”

“There must be something.”

He shrugged.

Mistress Borfero puffed out her cheeks. Everything she had she’d made by tickling out people’s desires. She was not sure what to do with a person who had none. “Well, why don’t you think about it?”

Friendly slowly nodded. “I will think.”

“Did you see two Northmen drinking on your way in?”

“I saw two Northmen. One was reading a book.”

“Really? A book?”

Friendly shrugged. “There are readers everywhere.”

She swept through the place, noting the disappointing lack of wealthy custom and estimating just how dismal this evening’s profits were likely to be. If one of the Northmen had been reading, he had given up. Deep was drinking some of her best wine straight from the bottle. Three others lay scattered, empty, beneath the table. Shallow was smoking a chagga pipe, the air thick with the stink of it. Borfero did not allow it normally, but she was obliged to make an exception for these two. Why the bank chose to employ such repugnant specimens she had not the slightest notion. But she supposed rich people need not explain themselves.

“Gentlemen,” she said, insinuating herself into a chair.

“Where?” Shallow gave a croaky laugh. Deep slowly tipped his bottle up and eyed his brother over the neck with sour disdain.

Borfero continued in her business voice, soft and reasonable. “You said your … employers would be most grateful if I came upon … that certain item you mentioned.”

The two Northmen perked up, both leaning forward as though drawn by the same string, Shallow’s boot catching an empty bottle and sending it rolling in an arc across the floor.

“Greatly grateful,” said Deep.

“And how much of my debt would their gratitude stretch around?”

“All of it.”

Borfero felt her skin tingling. Freedom. Could it really be? In her pocket, even now? But she could not let the size of the stakes make her careless. The greater the payoff, the greater the caution. “My debt would be finished?”

Shallow leaned close, drawing the stem of his pipe across his stubbled throat. “Killed,” he said.

“Murdered,” growled his brother, suddenly no farther off on the other side.

She in no way enjoyed having those scarred and lumpen killers’ physiognomies so near. Another few moments of their breath alone might have done for her. “Excellent,” she squeaked, and slipped the package onto the table. “Then I shall cancel the interest payments forthwith. Do please convey my regards to … your employers.”

“’Course.” Shallow did not so much smile as show his sharp teeth. “Don’t reckon your regards’ll mean much to them, though.”

“Don’t take it personally, eh?” Deep did not smile. “Our employers just don’t care much for regards.”

Borfero took a sharp breath. “Tough times all over.”

“Ain’t they, though?” Deep stood, and swept the package up in one big paw.

* * *

The cool air caught Deep like a slap as they stepped out into the evening. Sipani, none too pleasant when it was still, had a decided spin to it of a sudden.

“I have to confess,” he said, clearing his throat and spitting, “to being somewhat on the drunk side of drunk.”

“Aye,” said Shallow, burping as he squinted into the mist. At least that was clearing somewhat. As clear as it got in this murky hell of a place. “Probably not the bestest notion while at work, mind you.”

“You’re right.” Deep held the baggage up to such light as there was. “But who expected this to just drop in our laps?”

“Not I, for one.” Shallow frowned. “Or for … not one?”

“It was meant to be just a tipple,” said Deep.

“One tipple does have a habit of making itself into several.” Shallow wedged on that stupid bloody hat. “A little stroll over to the bank, then?”

“That hat makes you look a fucking dunce.”

“You, brother, are obsessed with appearances.”

Deep passed that off with a long hiss.

“They really going to score out that woman’s debts, d’you think?”

“For now, maybe. But you know how they are. Once you owe, you always owe.” Deep spat again, and, now that the alley was a tad steadier, tottered off with the baggage clutched tight in his hand. No chance he was putting it in a pocket where some little scab could lift it. Sipani was full of thieving bastards. He’d had his good socks stolen last time he was here, and worked up an unpleasant pair of blisters on the trip home. Who steals socks? Styrian bastards. He’d keep a good firm grip on it. Let the little fuckers try to take it then.

“Now who’s the dunce?” Shallow called after him. “The bank’s this way.”

“Only we ain’t going to the bank, dunce,” snapped Deep over his shoulder. “We’re to toss it down a well in an old court just about the corner here.”

Shallow hurried to catch up. “We are?”

“No, I just said it for the laugh, y’idiot.”

“Why down a well?”

“Because that’s how he wanted it done.”

“Who wanted it done?”

“The boss.”

“The little boss, or the big boss?”

Even drunk as Deep was, he felt the need to lower his voice. “The bald boss.”

“Shit,” breathed Shallow. “In person?”

“In person.”

A short pause. “How was that?”

“It was even more than usually terrifying, thanks for reminding me.”

A long pause, with just the sound of their boots on the wet cobbles. Then Shallow said, “We better hadn’t do no fucking up of this.”

“My heartfelt thanks,” said Deep, “for that piercing insight. Fucking up is always to be avoided when and wherever possible, wouldn’t you say?”

“Y’always aim to avoid it, of course you do, but sometimes you run into it anyway. What I’m saying here is, we’d best not run into it.” Shallow dropped his voice to a whisper. “You know what the bald boss said last time.”

“You don’t have to whisper. He ain’t here, is he?”

Shallow looked wildly around. “I don’t know. Is he?”

“No, he ain’t.” Deep rubbed at his temples. One day he’d kill his brother, that was a foregone conclusion. “That’s what I’m saying.”

“What if he was, though? Best to always act like he might be.”

“Can you shut your mouth just for a fucking instant?” Deep caught Shallow by the arm and stabbed the baggage in his face. “It’s like talking to a bloody—” He was greatly surprised when a dark shape whisked between them and he found his hand was suddenly empty.

* * *

Kiam ran like her life depended on it. Which it did, o’ course.

“Get after him, damn it!” She heard the two Northmen flapping and crashing and blundering down the alley behind, and nowhere near far enough behind for her taste.

“It’s a girl, y’idiot!” Big and clumsy but fast they were coming, boots hammering and hands clutching, and if they once caught ahold of her …

“Who fucking cares? Get the thing back!” And her breath hissing and her heart pounding and her muscles burning as she ran.

She skittered around a corner, rag-wrapped feet sticking to the damp cobbles, the way wider, lamps and torches making muddy smears in the mist and people busy everywhere. She ducked and weaved, around them, between them, faces looming up and gone. The Blackside night market, stalls and shoppers and the cries of the traders, full of noise and smells and tight with bustle. Kiam slithered between the wheels of a wagon, limber as a ferret, plunged between buyer and seller in a shower of fruit, then slithered across a stall laden with slimy fish while the trader shouted and snatched at her, caught nothing but air. She stuck one foot in a basket and was off, kicking cockles across the street. Still she heard the yells and growls as the Northmen knocked folk flying in her wake, crashes as they flung the carts aside, as though a mindless storm were ripping apart the market behind her. She dived between the legs of a big man, rounded another corner, and took the greasy steps two at a time, along the narrow path by the slopping water, rats squeaking in the rubbish and the sounds of the Northmen now loud, louder, cursing her and each other. Her breath whooping and cutting in her chest, she ran desperate, water spattering and spraying around her with every echoing footfall.

“We’ve got her!” the voice so close at her heels. “Come here!”

She darted through that little hole in the rusted grate, a sharp tooth of metal leaving a burning cut down her arm, and for once she was plenty glad that Old Green never gave her enough to eat. She kicked her way back into the darkness, keeping low, lay there clutching the package and struggling to get her breath. Then they were there, one of the Northmen dragging at the grating, knuckles white with force, flecks of rust showering down as it shifted, and Kiam stared and wondered what those hands would do to her if they got their dirty nails into her skin.

The other one shoved his bearded face in the gap, a wicked-looking knife in his hand, not that someone you just robbed ever has a nice-looking knife. His eyes popped out at her and his scabbed lips curled back and he snarled, “Chuck us that baggage and we’ll forget all about it. Chuck us it now!”

Kiam kicked away, the grate squealing as it bent. “You’re fucking dead, you little piss! We’ll find you, don’t worry about that!” She slithered off, through the dust and rot, wriggled through a crack between crumbling walls. “We’ll be coming for you!” echoed from behind her. Maybe they would be as well, but a thief can’t spend too much time worrying about tomorrow. Today’s shitty enough. She whipped her coat off and pulled it inside out to show the faded green lining, stuffed her cap in her pocket and shook her hair out long, then slipped onto the walkway beside the Fifth Canal, walking fast, head down.

A pleasure boat drifted past, all chatter and laughter and clinking of glass, people moving tall and lazy on board, strange as ghosts seen through that mist, and Kiam wondered what they’d done to deserve that life and what she’d done to deserve this, but there never were no easy answers to that question. As it took its pink lights away into the fog she heard the music of Hove’s violin. Stood a moment in the shadows, listening, thinking how beautiful it sounded. She looked down at the package. Didn’t look much for all this trouble. Didn’t weigh much, even. But it weren’t up to her what Old Green put a price on. She wiped her nose and walked along close to the wall, music getting louder, then she saw Hove’s back and his bow moving, and she slipped behind him and let the package fall into his gaping pocket.

* * *

Hove didn’t feel the drop, but he felt the three little taps on his back, and he felt the weight in his coat as he moved. He didn’t see who made the drop and he didn’t look. He just carried on fiddling, that Union march with which he’d opened every show during his time on the stage in Adua, or under the stage, at any rate, warming up the crowd for Lestek’s big entrance. Before his wife died and everything went to shit. Those jaunty notes reminded him of times past, and he felt tears prickling in his sore eyes, so he switched to a melancholy minuet more suited to his mood, not that most folk around here could’ve told the difference. Sipani liked to present itself as a place of culture, but the majority were drunks and cheats and boorish thugs, or varying combinations thereof.

How had it come to this, eh? The usual refrain. He drifted across the street like he’d nothing in mind but a coin for his music, letting the notes spill out into the murk. Across past the pie stall, the fragrance of cheap meat making his stomach grumble, and he stopped playing to offer out his cap to the queue. There were no takers, no surprise, so he headed on down the road to Verscetti’s, dancing in and out of the tables on the street and sawing out an Osprian waltz, grinning at the patrons who lounged there with a pipe or a bottle, twiddling thin glass stems between gloved fingertips, eyes leaking contempt through the slots in their mirror-crusted masks. Jervi was sat near the wall, as always, a woman in the chair opposite, hair piled high.

“A little music, darling?” Hove croaked out, leaning over her and letting his coat dangle near Jervi’s lap.

* * *

Jervi slid something out of Hove’s pocket, wrinkling his nose at the smell of the old soak, and said, “Fuck off, why don’t you?” Hove moved on and took his horrible music with him, thank the Fates.

“What’s going on down there?” Riseld lifted her mask for a moment to show that soft, round face, well powdered and fashionably bored.

There did indeed appear to be some manner of commotion up the street. Crashing, banging, shouting in Northern.

“Damn Northmen,” he murmured. “Always causing trouble, they really should be kept on leads like dogs.” Jervi removed his hat and tossed it on the table, the usual signal, then leaned back in his chair to hold the package inconspicuously low to the ground beside him. A distasteful business, but a man has to work. “Nothing you need concern yourself about, my dear.”

She smiled at him in that unamused, uninterested way which, for some reason, he found irresistible.

“Shall we go to bed?” he asked, tossing a couple of coins down for the wine.

She sighed. “If we must.”

And Jervi felt the package spirited away.

* * *

Sifkiss wriggled out from under the tables and strutted along, letting his stick rattle against the bars of the fence beside him, package swinging loose in the other. Maybe Old Green had said stay stealthy but that weren’t Sifkiss’ way anymore. A man has to work out his own style of doing things, and he was a full thirteen, weren’t he? Soon enough now he’d be passing on to higher things. Working for Kurrikan maybe. Anyone could tell he was marked out special—he’d stole himself a tall hat that made him look quite the gent about town—and if they were dull enough to be entertaining any doubts, which some folk sadly were, he’d perched it at quite the jaunty angle besides. Jaunty as all hell.

Yes, everyone had their eyes on Sifkiss.

He checked he wasn’t the slightest bit observed, then slipped through the dewy bushes and the crack in the wall behind, which honestly was getting to be a bit of a squeeze, into the basement of the old temple, a little light filtering down from upstairs.

Most of the children were out working. Just a couple of the younger lads playing with dice and a girl gnawing on a bone and Pens having a smoke and not even looking over, and that new one curled up in the corner and coughing. Sifkiss didn’t like the sound o’ those coughs. More’n likely he’d be dumping her off in the sewers a day or two hence but, hey, that meant a few more bits corpse money for him, didn’t it? Most folk didn’t like handling a corpse, but it didn’t bother Sifkiss none. It’s a hard rain don’t wash someone a favor, as Old Green was always saying. She was way up there at the back, hunched over her old desk with one lamp burning, her long grey hair all greasy-slicked and her tongue pressed into her empty gums as she watched Sifkiss come up. Some smart-looking fellow was with her, had a waistcoat all silver leaves stitched on fancy, and Sifkiss put a jaunt on, thinking to impress.

“Get it, did yer?” asked Old Green.

“’Course,”said Sifkiss, with a toss of his head, caught his hat on a low beam, and cursed as he had to fumble it back on. He tossed the package sourly down on the tabletop.

* * *

“Get you gone, then,” snapped Green.

Sifkiss looked surly, like he’d a mind to answer back. He was getting altogether too much mind, that boy, and Green had to show him the knobby-knuckled back of her hand ’fore he sloped off.

“So here you have it, as promised.” She pointed to that leather bundle in the pool of lamplight on her old table, its top cracked and stained and its gilt all peeling, but still a fine old piece of furniture with plenty of years left. Like to Old Green in that respect, if she did think so herself.

“Seems a little luggage for such a lot of fuss,” said Fallow, wrinkling his nose, and he tossed a purse onto the table with that lovely clink of money. Old Green clawed it up and clawed it open and straight off set to counting it.

“Where’s your girl Kiam?” asked Fallow. “Where’s little Kiam, eh?”