Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Writers' relationships with their surroundings are seldom straightforward. While some, like Jane Austen and Thomas Mann, wrote novels set where they were staying (Lyme Regis and Venice respectively), Victor Hugo penned Les Misérables in an attic in Guernsey and Noël Coward wrote that most English of plays, Blithe Spirit, in the Welsh holiday village of Portmeirion. Award-winning BBC drama producer Adrian Mourby follows his literary heroes around the world, exploring 50 places where great works of literature first saw the light of day. At each destination – from the Brontës' Yorkshire Moors to the New York of Truman Capote, Christopher Isherwood's Berlin to the now-legendary Edinburgh café where J.K. Rowling plotted Harry Potter's first adventures – Mourby explains what the writer was doing there and describes what the visitor can find today of that great moment in literature. Rooms of One's Own takes you on a literary journey from the British Isles to Paris, Berlin, New Orleans, New York and Bangkok and unearths the real-life places behind our best-loved works of literature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

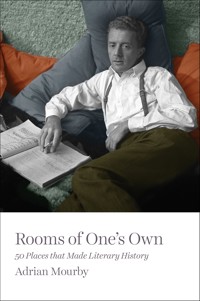

Rooms of One’s Own

50 Places that Made Literary History

ADRIAN MOURBY

To my wife Kate Companion for fourteen years of these travels

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Many of the places visited in this book are open to the general public. Some are in private hands with no right of access. Others are operated by bodies like the National Trust. Some took many approaches before access was agreed. It’s always best to make contact well in advance before visiting, and of course sometimes you will have to accept no for answer.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Virginia Woolf famously said that, if she is to write fiction, ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own’.

This book explores how male and female writers have over the last two centuries found rooms that inspired them to write, from Tennessee Williams’ garret in New Orleans to the room with a view that E.M. Forster coveted in Florence.

En route I was able discover something of Damon Runyon’s New York, Graham Greene’s Saigon, and George Sand’s Venice.

Not every great writer or every room that has witnessed great literature has made it into these 50 chapters. This was very much a personal quest in pursuit of writers who interested me and I didn’t want to spend too much time in birthplaces that have been turned into well-meaning museums.

For some of the authors in this book, sitting in the right room was all-important. Marcel Proust’s housekeeper claimed that having to relocate from the apartment where he began À la recherche du temps perdu exacerbated his ill-health and hastened his death, leaving that ambitious novel sequence incomplete. Victor Hugo spent a fortune turning his house on Guernsey into a very personal Hugo theme park.

For other writers the room can become a location in their fiction. H.G. Wells set one of his bestselling works, Mr Britling Sees It Through, in his own house in Essex. Olivia Manning used her own Cairo flat in the Levant Trilogy. But others had no need for their subject matter to be in front of them. James Joyce wrote exclusively about Dublin while sitting in his favourite Paris restaurants.

Over the last few years I’ve visited rooms where the author’s presence is almost palpable in the arrangement of every individual object, and others that seem to bear no relationship to the author or the work produced there.

Some writers have preferred to work in a favourite café – J.K. Rowling is only a recent example in a line that stretches back well beyond Sartre. Oscar Wilde liked to write and entertain in expensive hotels but Hemingway and Noël Coward stayed in the best hotels around the world simply because they could. They could write well regardless of their surroundings.

I’ve also followed my writers into pubs, apartments, holiday cottages and homes that are now literary museums.

There are some surprises along the way: young Norman Mailer, staying in his parents’ apartment, trying to have a conversation by the mailboxes with the diffident playwright who lived downstairs and concluding that Arthur Miller could go to hell; Erich Maria Remarque locked in the bathroom by Marlene Dietrich when the Nazis came to visit; a delirious Somerset Maugham overhearing the manageress of his hotel asking the doctor to remove him to hospital as a death would be bad for business.

This book consists of 50 literary pilgrimages – to London, Oxford, Paris, Berlin and St Petersburg, as well as to Italy, America, North Africa and the Far East. I didn’t just want to write about writers beavering away in the family’s spare room so I followed many on their travels – because writers do love to travel. Sometimes they are seeking the ideal place in which to work, sometimes they are escaping from life at home. Often they are travelling because their success makes it possible and they know all they need is a pen and paper – or laptop – to continue writing and so they seize on invitations with alacrity.

There is always something to be learned when you visit the place where a book was written. Sometimes the location features directly in what ends up on the page, but more often than not it’s significantly altered. We expect writers to be good at their craft and we like them to be inspired by their surroundings, but we can’t expect them to be honest as well.

Adrian Mourby, 2017

ROOMS OF ONE’S OWN

ITALY

HOTEL DANIELI, VENICE – GEORGE SAND (1804–76)

I arrived in Venice one chilly January many years ago when the Adriatic was seeping, slowly but relentlessly, across Riva degli Schiavoni. It was exactly 160 years previously that Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin picked her way along this quayside. It wasn’t difficult to discover her story. She is commemorated by an inscription within a particular bedroom in Venice’s first commercial hotel.

Aurore Dupin was one of Hotel Danieli’s earliest celebrity guests. When she arrived in January 1834 she was trailing scandal and her new lover, the poet Alfred de Musset.

Today Aurore is better known as George Sand, a pen name she adopted in her twenties, just as she adopted masculine attire and male smoking habits. At the age of 27 she left her husband and entered upon a four-year period of rebellion that included affairs with prominent writers and the production of a large number of books. That same year, 1831, she published her first novel, Rose et Blanche, written in collaboration with her then-lover Jules Sandeau, but for her next novel Indiana (1832) she adopted the pen name George Sand. By 1833 Sand had moved on to an affair with the young poet and dramatist Alfred de Musset.

Seven years older than the 23-year-old poet, Sand was keen that they should travel together to Italy where she wished to set her next book. This meant leaving behind her two children (aged five and ten) but the novelist was more concerned with getting the blessing of de Musset’s mother for their journey. The two women met in Sand’s carriage outside Mme de Musset’s Paris home. Evidently Maman was overwhelmed by Sand’s eloquence and promises to take great care of the young man.

The couple took a carriage from Paris to Marseille where they boarded a steamer to Livorno, arriving in January 1834 to a very grey Venice. They took a suite of rooms at the Danieli in what is now Room 10, overlooking Riva degli Schiavoni.

By the time the lovers had unpacked, their six-month romance was cooling. On the journey south Sand had shocked de Musset by her conversation, regaling other passengers with the fact that she was born within a month of her parents’ marriage, and with steamy stories of her mother’s affairs during the Napoleonic Wars. George Sand courted outrage.

In 1834 the commercial hotel ‘Danieli’ was still something of a new venture in Venice. For centuries this building close to the Doge’s palace had been known as Palazzo Dandalo. By the time of Napoleon’s forcible dissolution of the Venetian republic in 1797, the owners had ceased to maintain it. In 1822 an entrepreneur from nearby Fiuli called Giuseppe Dal Niel rented the piano nobile (first floor) of Palazzo Dandalo. In it he accommodated paying guests. By 1824, business was good enough to convince Dal Niel that there was a market for such a venture in Venice and he bought the entire building, lavishly restoring it and converting it into a hotel, to which he gave his Venetian nickname, ‘Danieli’.

As a palazzo of the nobility, the building’s main entrance had been to the side on Rio del Vin for gondola access, but as a hotel it needed a door directly onto the quayside of Riva degli Schiavoni. Dal Niel remodelled this facade to create a Gothic doorway and it was on the first floor immediately above this door that George Sand and Alfred de Musset took a suite with superb views. On a clear day you could see beyond the island of San Giorgio di Maggiore to Lido.

When I stepped off the vaporetto in 1994 Hotel Danieli was immediately recognisable by its pink facade and pointed ogee windows. I crossed the Ponte del Vin over a narrow canal to reach it. The old stone bridge is much busier today than it would have been in 1834. These days Venice is almost submerged by tourists, but at the beginning of the nineteenth century it was a shadow of its former proud and prosperous self, struggling as a new Habsburg appendage, thanks to Napoleon.

Inside the hotel lobby I made my way through costumed revellers to the concierge’s desk at the bottom of a great stone staircase. Originally this had stood open to the skies in the days when it was the palazzo’s courtyard, but Dal Niel glassed it over. Descending this staircase has since become one of the most splendid ways to make an entrance in Venice. As I arrived it was serving that function for a huge party of wealthy Egyptian and Lebanese wedding guests. Every night they were dining – in extravagant Carnival dress – at a different palazzo.

Although Sand and de Musset were in Venice during the period preceding Lent when ‘Carnevale’ had been celebrated for centuries, the festival had been banned in 1797 by the Habsburgs, and the wearing of masks was outlawed on moral grounds. Carnevale was not revived in George Sand’s time. In fact in its present exotic and erotic form, it is essentially a 1980s phenomenon.

By contrast Venice in the 1830s had very little to offer in terms of diversion. De Musset did manage to quickly lose a lot of Sand’s money at the Casino, however – and then fall ill from a combination of nervous exhaustion and alcohol.

The manager showed me up to Room 10 where George Sand nursed her highly-strung lover for a few weeks before losing patience with him. Sand was not the kind of woman who found fulfilment tending to those who coped less well with the world than she. Five years later on Mallorca, in the winter of 1838–9, she would similarly lose patience with the morbidity of her more famous lover, Frédéric Chopin.

Sand herself always worked at a phenomenal rate, producing 43 (now mostly unread) novels in her lifetime. While in Room 10 she was working on her tenth, André (published 1834) and her new Italian novel Simon (1835). She claimed to write from eight to thirteen hours a day.

The Room 10 that I saw was decorated in shades of pale green and its floor-space was reduced in size by a bathroom and fitted wardrobes. Nevertheless it retains that wonderful view across to San Giorgio. Someone has gallantly stencilled ‘Alfredo de Musset e George Sand MDCCCXXXIII–XXXIV’ over the partition, but Room 10 was hardly a love nest. De Musset was not just ill, but jealous and hysterical in turns. He rightly suspected that Sand was taking solace in the company of the doctor she had called to help with her increasingly deranged lover. Dr Pietro Pagello was both young and handsome. Very soon he had cured de Musset of his vapours and cured Sand of any remaining love for her poet. De Musset accepted the situation and left for Paris on 29 March. Sand and the doctor stayed on in Venice until August when she took him to Paris, but soon decided he was dull, and abandoned him.

Today Sand’s novels have fallen out of fashion and, like Vita Sackville-West, she is better known for her lifestyle than her literature. Photographs do not show a sexual siren but a rather podgy, heavy-featured middle-aged woman. Nevertheless her energy and her daring insistence on a woman’s right to take lovers, as men took mistresses, clearly had an impact on those who encountered her.

Chopin claimed to be repulsed by Sand on their first meeting, but he nevertheless fell under her spell. She would eventually parody their relationship in the novel LucreziaFloriani (1846), in which Chopin was the model for a sickly Eastern European prince named Karol, while Sand is Lucrezia, a middle-aged actress past her prime, who suffers for caring too much about the selfish Prince Karol.

The Danieli had many distinguished guests after George Sand, including Wagner, Dickens and Benjamin Britten, but it’s unlikely that any of them loved so passionately nor grew so quickly disenchanted as George Sand and her ‘Alfredo’.

PALAZZO BARBARO, VENICE – HENRY JAMES (1843–1916)

Before Hollywood decided en masse that Paris was the most romantic city in the world, wealthy Americans were besotted with Italy. This love affair continued throughout the nineteenth century. Rome and Florence were very popular among the American expat community, and so was Venice.

Of all the crumbling palaces patronised by American visitors none was such a favourite as Palazzo Barbaro on the Grand Canal near Accademia Bridge. As an enthusiast for the ‘Barbaro Circle’ I’ve often gazed over at it and thought about the writers and artists who had the good fortune to stay there.

It’s a fine Gothic structure made up of two interlinked palaces. The first, on the left if you are looking at them from the Grand Canal, was built in 1425 by Giovanni Bon, one of Venice’s master stonemasons, for the Spiera family. In 1465 it was bought by Zaccaria Barbaro, who was Procurator of San Marco, the second most important office in Venice.

The palazzo on the right was built two centuries later in the Baroque style by the architect Antonio Gaspari for the Tagliapietra family, one of the 30 families allowed to sit in the Great Council. As this was only a two-storey palazzo, the Tagliapietras gave permission for Gaspari to build over it in 1694, adding a lofty ballroom for the Barbaro family. The stuccoed and gilded ballroom was decorated by Sebastiano Ricci’s titillating painting ‘The Rape of the Sabine Women’ and frescoes by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta.

The American connection was not established until 1881 when two floors of the older palazzo were rented by Daniel Sargent Curtis, a cousin of the American portraitist John Singer Sargent. Curtis purchased his floors outright four years later, and set about restoring them with his wife Ariana. The couple soon made Palazzo Barbaro the centre of American artistic life in Venice. John Singer Sargent visited and famously painted a portrait of Daniel’s daughter-in-law, Mrs Ralph Curtis, in a white ball-gown.

The painters Anders Zorn, Claude Monet and James McNeill Whistler also visited and worked at Palazzo Barbaro. Visiting writers included Robert Browning, Edith Wharton, and that lover of Europe’s grand houses, Henry James.

James and Palazzo Barbaro, both of them overwrought and yet secretive, were a perfect match. James had first visited the city in 1869 as a bearded young disciple of John Ruskin. He was immediately taken with the city, but recorded that he would never get to know it from within. When in 1894 his close friend, the novelist Constance Fenimore Woolson, committed suicide in Venice by throwing herself from a palazzo casement, Venice became a darker place in James’ imagination. In 1899 he noted that a Venetian palazzo’s ‘beautiful blighted rooms’ could be the setting of a novel about the owners’ fallen fortunes.

James included Venice in his travel writing, From Venice to Strassburg (1873) and Italian Hours (1909). In between, while staying as a guest of the Curtises, he finished writing his 1888 novella, The Aspern Papers – based on a true story that he deliberately transplanted to Venice to spare blushes – and the desk at which he worked is still in the palace today. It’s a rather elaborate bureau in black lacquer with Chinese figures picked out in gold. Later James used the palazzo as a setting in his novel, The Wings of the Dove (1902). With his customary discretion he disguised Barbaro as Palazzo Leporelli, but it’s clear that his lengthy description of the ballroom is a pen portrait of the Barbaro’s – which James told everyone was the finest example of a Venetian Baroque interior.

Like many tourists, I’ve often photographed Palazzo Barbaro from Dorsoduro and the Accademia bridge. Until recently much of it was owned by the Curtis family and the doorbell on Fondamenta Barbaro still reads ‘Curtis’ in black letters.

When the Italian bicycle magnate Ivano Beggio bought the palazzo, I contacted an Italian academic who had befriended him on Facebook and managed to gain access through her. The open courtyard has the Curtis family’s huge black gondola drawn up on the cobbles, and there are steep steps up to the piano nobile. I noticed a lot of plaster had fallen off the external walls.

Even in Henry James’ time the palazzo was a shadow of its former self. When the Barbaro family died in the 1850s, much that could be sold off was, including all its Tiepolos and a collection of books that was said to be one of the best private libraries in Venice. But the portego, a corridor linking the drawing rooms, was broad and gracious and I could imagine James relishing the sense of calm that comes from so much space.

Nevertheless, while James was writing – and sleeping – in the Barbaro’s third floor all this decayed grandeur proved inspirational. So much that could be innocent and beautiful in life is, in Henry James’ novels, soured. In Venice he found an apt metaphor for that world view.

GRAND HÔTEL DES BAINS, VENICE – THOMAS MANN (1875–1955)

Thomas Mann’s Der Tod in Venedig (Death in Venice) is a book shot through with sadness. Mann wrote the novella, today one of his most popular stories, after staying at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on Venice’s Lido in 1911. Like Gustav von Aschenbach, the artistic hero of the book, Mann became fascinated by a beautiful young Polish boy whose family were also staying at the hotel. Mann based his hero Aschenbach on Gustav Mahler, whom he had met in Vienna and who’d recently died of a heart attack, but whereas Mahler expired at the peak of his creative powers, Aschenbach is depicted as suffering writer’s block.

The boy was later identified as ten-year-old Baron Władysław Moes, whose first name was usually shortened to Władzio. Thomas Mann’s wife insisted that her husband never followed Władzio round Venice as Aschenbach followed his beloved ‘Tadzio’. Nevertheless many believe the book hints at suppressed homoerotic tendencies, which were confirmed twenty years after Mann’s death when his diaries were published.

I can’t help thinking that in the years to come the underlying sadness in the book touched both the hotel and the young boy. At the end of his life, Baron Moes recalled that summer in 1911 in an interview: ‘I was considered to be a very beautiful child and women admired and kissed me when I walked along the promenade. Some of them sketched and painted me … The writer must have been highly impressed by my unconventional clothes and he described them without missing a detail: a striped linen suit and a red bow-tie as well as my favourite blue jacket with gold buttons.’

The long ‘Edwardian summer’ of European peace was about to end, however. The First World War would see Thomas Mann’s country in conflict with Italy and during the Second World War Germany held Władzio captive for six years. In 1945, after the cessation of hostilities, all his property was confiscated by the new Communist regime in Poland. He died in 1986 before his country managed to throw off the government that had been imposed upon it after a war that, ironically, had been started to save Poland from foreign invasion.

The Grand Hôtel des Bains had a less traumatic time in the twentieth century, but is a sorry sight if you visit it today. By a fitting coincidence it opened in 1900, the same year that Władzio was born. This was Venice’s first great resort hotel, built on the spit of land known as Lido that separates the Venetian lagoon from the Adriatic. It was indeed a splendid sight, with a porticoed entrance held up by eight Corinthian columns, four floors of bedrooms, and beautifully manicured grounds. The hotel attracted wealthy Italians as well as European aristocrats seeking sunshine, and celebrities like the ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev (who entertained his many lovers at Hôtel des Bains, and in 1929 died there).

The opening of a private airport at Nicelli on the northernmost tip of Lido (three kilometres from Hôtel des Bains) and the patronage of the charismatic poet, politician and aviator Gabriele D’Annunzio, only increased its appeal. But the Grand Hôtel des Bains was always cut off from the seaside by its garden and by the long beach road, now known as Lungomare Guglielmo Marconi. It was soon to be eclipsed by the opening of the much larger Grand Hotel Excelsior in 1908. The Excelsior had the advantage of being directly on the beach, and its lobby could be accessed by motor launches coming from Venice via a specially-dug canal. This was a twentieth-century hotel in an over-the-top Moorish style while Hôtel des Bains remained rooted in the nineteenth. All the older lady could do to compete was to create a pedestrian tunnel under Lungomare Guglielmo Marconi.

After the Second World War the gradual rediscovery of Venice itself as a destination meant that Lido faced increased competition. It was likely that only one major hotel could survive long-term.

As guest numbers dwindled, the hotel’s beach and exteriors were used by Visconti in 1971 when he filmed Death in Venice, although its interiors were shot on a sound stage in Cinecittà in Rome. Visconti memorably emphasised the parallels with Mahler by making his Aschenbach – played by Dirk Bogarde – a composer rather than author. Hôtel des Bains was also used as a movie location in the 1996 film of The English Patient, but in 2010 the hotel closed for good. It was going to be converted into a luxury apartment complex called Residenze des Bains. Five years later, though, when I last looked over the fence that currently surrounds it, no work was going on and the portico was boarded up.

Der Tod in Venedig was a success for Thomas Mann, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 and the Goethe Prize in 1949. The film of it was also good for the careers of Dirk Bogarde and Visconti, and helped revive interest in Mahler’s work, but 1911 proved to be a high-water mark for Baron Władysław Moes, and the hotel on Lido that welcomed in his family that summer.

GRITTI PALACE, VENICE – ERNEST HEMINGWAY (1899–1961)

Ernest Hemingway came to Venice a number of times in his adventurous 61 years. More than anyone else perhaps, this heavy-drinking American novelist exemplifies our idea of the twentieth-century writer as traveller to exotic places and lover of expensive hotels. Paris and Pamplona, Cuba and Kenya were Hemingway’s destinations of choice. He also had a particular soft spot for northern Italy, where as a young man he had seen very brief service in the First World War as a field medic.

The island of Torcello and the south-east end of the Grand Canal were Hemingway’s stomping grounds in Venice. He liked Harry’s, a compact super-expensive cocktail bar opposite Santa Maria della Salute where both the Bellini cocktail and carpaccio were invented. Hemingway claimed to have had a hand in crafting its dry martini, which is served in a small glass without a stem and is made with ten parts gin to one part vermouth. This is an adaptation of the Montgomery (fifteen parts gin to one part dry vermouth).

Most assertions that Hemingway made about himself have to be viewed with caution, however. He was such a fabulist that it can be difficult to separate his own exotic, wealthy and highly successful literary life from the boasts he made about it. Venice proved the location for one of the most outrageous – and embarrassing – autobiographical fictions Hemingway ever wove. Here was the setting for the ‘love affair’ that spawned his novella Across the River and into the Trees. It was begun in Italy in 1948 and revised at the Gritti Palace in 1950, the hotel getting a walk-on role in the novel.

The Gritti Palace, which stands half a kilometre west of Harry’s Bar, was commissioned as a Grand Canal palazzo by the Pisani family in 1475 and later bought by Doge Andrea Gritti. Its canal facade once had vivid frescoes by Giorgione but now it presents a plain brick face, broken up only by narrow stone casements to passing vaporetti.

After decades of use as lodgings for visiting diplomats, Palazzo Pisani Gritti became in the nineteenth century an annexe to the Grand Hotel Venice next door. An upper storey to accommodate less wealthy guests was added. John and Effie Ruskin came to stay in 1849, soon after their famously disastrous honeymoon. Ruskin of course preferred the original sections of the building, praising the capitals of the Palazzo Pisani Gritti’s first-floor windows as ‘singularly spirited and graceful’ in his Stones of Venice.

My wife and I also stayed at the Gritti soon after our wedding – much more pleasantly than did the Ruskins – and we went back in 2013 just as the hotel completed a major refurbishment. Those renovations included remodelling the Hemingway Suite, which had been created out of first-floor rooms 115 and 117, where it was understood the author had stayed in 1950. Of course we wanted to stay in his room – but then so did everyone else in 2013.

We did get to look around and take photos, however. Compared with many ‘famous author’ rooms around the world, this one is pretty authentic. Hemingway was a major celebrity in the years 1948–50 when he visited Venice, and so much relating to him was preserved. When the Gritti closed for eighteen months of refurbishment 65 years later, every item of furniture, every picture and Murano glass chandelier was labelled and stored, and its original position marked, which is why I could be fairly certain that Papa Hemingway must have sat in that unremarkable low green chair in the corner of his drawing room with its well-stocked bar, models of his motor launch The Pilar and pieces of coral. I took my turn posing in the chair, I couldn’t help thinking he would have found the suite that bears his name a bit over-decorated, and more to the taste of ‘Miss Mary’, his hard-faced fourth wife who is pictured on the wall opposite. She and Papa are snapped standing on the terrace of the Gritti during one of her visits to the hotel. Hemingway, although not yet 50, looks prematurely grandpaternal in a tweed suit.

At the time that black and white photo was taken, both were recovering from recent injuries and infections, and Hemingway was infuriating Miss Mary with his latest infatuation. He had recently fallen for a young Venetian countess and amateur artist, Adriana Ivancich. She was only nineteen and unaware of the strength of his feelings. Frustrated, Hemingway poured his passion into the worst book he ever wrote. Across the River and into the Trees is a thinly-veiled fantasy in which an old American colonel, ‘marked for death’, is having an all-but-consummated affair with Renata, a young Venetian aristocrat. Hem began the book fuelled by crates of Amarone della Valpolicella supplied by Harry’s Bar round the corner.

Rereading this slim novel in Venice I felt rather sorry for the author, physically old before his time, staggering back to the Gritti at night or waking painfully early as light from the surface of the Grand Canal played on the ceiling above his bed. Did he drag a bottle of Valpolicella and the Herald Tribune to the lavatory with him, as his hero Colonel Cantwell does?

When the book came out, it was a critical disaster. Worse, Hemingway made the guilty mistake of dedicating his book of Adriana fantasies to Miss Mary. No wonder she looked so tight-lipped in that photo. Ironically, the critical mauling that Hemingway received for Across the River and into the Trees spurred him to hit back with The Old Man and the Sea, which won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. I’m sure, however, that Mary Hemingway would have had something tart to say about the fact that the cover illustration of that novel was drawn by the young woman he had fallen in love with in Venice.

Unaware of their fantasy love affair, Adriana subsequently took up the Hemingways’ invitation to visit the couple in Cuba. When Hemingway confessed his love, she was shocked. Moreover, her mother was appalled when Across the River and into the Trees was published in the States. Its insinuations might have damaged her daughter’s marriage prospects. Hemingway forbade the book’s publication in Italy for two years to spare her embarrassment. He might have done better not to have written it at all.

Ernest Hemingway committed suicide eleven years later in 1961, having lost the ability to write. Adriana, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, committed suicide in 1983 at the age of 53.

The Gritti Palace also has author suites dedicated to John Ruskin and W. Somerset Maugham. I just hope of the three of them that Maugham, even though he was not in the best of health at the time of his visits, had a happier time than Ruskin and Hemingway.

PIAZZA DI SPAGNA, ROME – JOHN KEATS (1795–1821)

For a writer who died almost unknown in 1821, it’s remarkable that John Keats is commemorated in not just one house but two. The Regency villa that the poet occupied with Charles Brown in John Street, Hampstead is now open to the public as Keats House (standing in what is now known as Keats Grove). Here the young Londoner and trainee doctor wrote many of his best poems, including the odes ‘To a Nightingale’ and ‘On a Grecian Urn’.

The second-floor apartment at Piazza di Spagna 26 in Rome, where Keats died at the age of 25, is also kept as a memorial to him. It’s known today as the Keats–Shelley House despite the fact that Shelley never visited Keats during his three months in this house. Shelley was, however, in Italy when he heard of Keats’ death and he wrote the poem ‘Adonaïs’ in response. In 1906 the house, also known as Casina Rossa, was purchased for the Keats Shelley Memorial Association, hence its name. Today it contains an archive of material relating to a range of British romantic poets, including Byron, Wordsworth, the Brownings, and Oscar Wilde.

The lure of the Keats–Shelley House is strong. It stands at the bottom of the picturesque Spanish Steps, known in Italian as Scalinata di Trinità dei Monti. These steps have featured in so many films – including Roman Holiday and The Talented Mr Ripley – that they’ve become a tourist attraction in their own right. However, in the eighteenth century when they were built, they served a purely practical function: linking the Trinità dei Monti church at the top of the Pincian Hill with the Bourbon-Spanish Embassy in Palazzo Monaldeschi below.

The monumental staircase – essentially a gigantic flight of Baroque garden steps – took from 1723 to 1725 to complete. The architects were Francesco de Sanctis and Alessandro Specchi. They wanted to frame the steps with two identical buildings at their base, which is why Babbington’s Tea Rooms at Piazza di Spagna 23 is an almost mirror image of the Keats–Shelley House on the opposite side.