9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

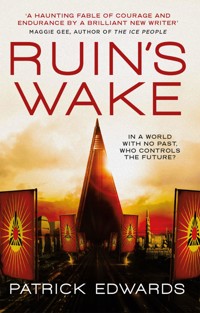

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A moving and powerful science fiction novel with themes of love, revenge and identity on a totalitarian world. Ruin's Wake imagines a world ruled by a totalitarian government, where history has been erased and individual identity is replaced by the machinations of the state. As the characters try to save what they hold most dear – in one case a dying son, in the other secret love – their fates converge to a shared destiny. An old soldier in exile embarks on a desperate journey to find his dying son. A young woman trapped in an abusive marriage with a government official finds hope in an illicit love. A female scientist uncovers a mysterious technology that reveals that her world is more fragile than she believed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Dr Song’s Journal

Groan

i. Karume

Endeldam

Dr Song’s Journal

Alec IV

ii. Quincentennial

The Field

iii. Stakes

Wreckers

Dr Song’s Journal

Hollow

iv. Underworld

Debrayn

Dr Song’s Journal

v. Hush

Sanatorium

Dr Song’s Journal

vi. Overlooked

Fleet Coast

vii. Complication

A Parting

Dr Song’s Journal

viii. Knife

Cypher

Flight

Buried

Unification

Illumination

Revolution

By Blood

Renewal

Dr Song’s Journal

Heartfelt thanks go to

About the Author

Ruin’s WakePrint edition ISBN: 9781785658792E-book edition ISBN: 9781785658808

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 201910 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2019 Patrick Edwards

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Al,

who made it all happen

Bask 2 – 498

I had to rid myself of Melthum. The man was insufferable, and worse, unreliable. His bumbling efforts to manage my appointments and correspondence reflected poorly on me, and that I will not tolerate.

So much of position is dependent on keeping face here at the vaunted Karume Elucidon – I am measured not merely on the papers I write, but how well my department is organised, though I – like all of my faculty colleagues – couldn’t care less about the right forms going in the right bins, student assessment, inter-departmental statistics. The face of it – the conceit – is that efficiency is as vital as discovery, though in truth the former trumps the latter in this glorious Hegemony of the Seeker.

Melthum had been my assistant and occasional bed-warmer for so long I barely noticed him, no more than I would the pen I use to sign or the chair I pull up to my desk. I certainly noticed him when he tried to plead his case, bleating in that dreadful provincial accent of his. When he persisted, I slammed the door in his face and advised him to try the fucking military (which he never shut up about anyway). Maybe getting shot at in some border action would give him some vim – though I doubt, for all of his admiration and exaltation of the soldiery, he really has any intention of putting himself in harm’s way. Doubtless he’ll scratch at someone else’s door for his grant money, and there is enough vanity among the faculty that he’ll likely get it. Just not in my department.

Department – it sounds so grand. The name conjures images of shuffled papers and sage nodding in all-night pushes; rooms full of desks, the ceilings chattering with rapid keystrokes as serious boys and girls process important data and compile heavy archival volumes for posterity.

As it is, the Department of pre-Ruin Cryptoarchaeology comprises only myself, Professor Sulara Song, and two underachieving postgrads who couldn’t do any better (academically, as well as with each other) and, until recently, the assistant and administrator Melthum. Now my truncated ‘team’ of two is, I’m sure, as much looking forward to taking their directives from me as I am to addressing them directly.

On to the paperwork, in which the idiot barely made a dent despite ours being the smallest department in the Elucidon. I’ve requested a replacement, although, given how most of my formal requests die alone in a darkened corner of the Dean’s office, I’ll square my shoulders against a long haul of tedium.

Despite the drudgery, I can at least look forward to not seeing that rodent-like face peering around the door and the awkward silences when he assumed a few throwaway rolls in bed permitted him to see me as anything other than his superior.

Bask 9 – 498

I am packing up the department for the move to the Makuo glacier. Paperwork, endless reams of the stuff, dogs me at every turn. I would draft in the other two to help if I didn’t think their heads would implode from the need to consider more than one thing at a time.

So much to do, so much equipment to be requisitioned, so many permits to be filed. Moving house is hard enough in this city, let alone shifting a team of people three hundred klicks into the frozen north.

…but of course, I forget. With all that has gone on I neglected to keep this log updated. To wit:

The oaf Fermin marched into my office three days ago and stood in front of my desk looking mightily pleased with himself. Someone – presumably heralding imminent senility – decided the greasy shit was fit for an assistant professorship and now he struts about as if he owns the place. Come to think of it, he’s looked that way ever since the Elucidon overruled me in giving him a fail for his undergraduate Heritage module. In his eyes, that was quite the victory, I’m sure.

Anyway, I made sure Assistant Professor Fermin had a good wait before I raised my eyes to acknowledge him, and when I did so I just stared at him in silence. This had always made his upper lip sweat when he was a student, and it seemed nothing had changed. He fussed with his nails, shuffling from foot to foot, then blurted out what had obviously been meant as a triumphant, pre-prepared speech.

The survey I’d commissioned with his (ha!) department – Geology – had turned up some results. Again, I waited in silence. In fact, I began to drum my fingernails on the desk because I know how wickedly unnerving he finds it. The oaf spat it out – in the north, they’d found something that might be pre-Ruin. After a pause, I gave him some cold formal words of thanks and indicated he should leave the sheaf of papers on my desk. He dropped them and made for the door, and only at the last minute did he seem to regain some of his forced humour. His face took on a look halfway between elation and satisfaction – triumphant, you might call it. Despite myself I snapped at him, asking what was so wonderful that he felt the need to take up more of my time.

Maddeningly, he nodded at the papers on my desk.

‘You’ll see,’ he lisped.

Skies, I loathe him.

Ice, you see. Almost 1.5 kilometres of ice between the surface of the glacier and the bedrock, and in between all manner of fissures, faults, melt-lines and geological waste dumps. That was what the idiot was so happy about, because he knows I am obliged to go. It has been years since any undergraduate applied to major in Cryptarchaeology, which has whittled away at our share of the budget, our designation reduced to ‘research-only’ – just one step up from ‘shuttered’. We have scoured the old dig sites over and over, sucking every drop of evidence from them (which would fill a medium-sized beaker, at best). The Elucidon, taking its lead from the wider Hegemony, is touchy about anything to do with the pre-Ruin that is not an out-and-out condemnation; they would need little encouragement to allow the already obscure department to dry up and disappear – without me, I’m sure this would already have happened.

So, Fermin was right in his assumption – I have to go, and it will be hard going on me, a woman of middle age (the mirror tells me, unfailingly), and though I try to keep myself fit and healthy (erstwhile rolling with assistants, for example) I am hardly prepared for an expedition into the harsh ice fields.

But they have made a miscalculation, a misstep guided by male arrogance, pride and a lack of attention to detail that is particularly heinous, for all that they claim to be scientists. They assume I’m past it, ground down by the years and lacking the vitality necessary to make anything come of this; in truth, I cannot gather my things fast enough. The years are rolling off me as I prepare to do something, finally, after an aeon of mouldering in these rooms with the dregs of the student body to assist me. I’m an undergraduate again on my first field expedition, too full of excitement to know which warm liners to pack or which boots to wear.

There might be nothing up there more than a cavern or an intrusion of granite that has confounded poorly calibrated sensors; on the other hand, I might reach out and lay my fingers on something from before the world I know was made, and feel its legacy on my skin.

Bask 10 – 498

The Dean accepted my research proposal with alarming speed. I’m sure the rest of them are having a jolly good laugh about sending me off to freeze. He won’t be smiling when he sees the size of my equipment requirements. And they’d better give me an able assistant, or I’ll come back and haunt the bastards for ever.

Groan

Death had receded, and the flat expanse of the steppe welcomed the return of the pale, waking light. The ground was frozen below the surface but the cap ice had begun the slow melt, releasing its grip on the broken walls and streets of the old mining town. Ras’s burning arc was shallow and cast long shadows over the broken water tower, the old dormitories, the ore processors with their silent conveyors. The strip mine’s pit gaped, the great conical hole in the permafrost presenting its open maw to the milky sky. No one remembered the place’s real name. It was just the Groan. Nobody else came here any more.

Cale contemplated the white stone block in front of him while he got his breath back. It was taller than him, its rough-hewn sides criss-crossed with straps. The lifter-field unit he’d used to haul it out of the pit had barely held together and the block, even in the anti-grav bubble, had been cumbersome. It stood now, stark against the sky on the gravel apron that brimmed the lip of the pit as he ran a callused hand over it, feeling the roughness on his palm. This one would become his tenth Face, and he knew it would be his best. The pale granite stared back at him, flat, unyielding, devoid of the features that would emerge: jawline, brow, eyes, lips. There was still so much to do, so much preparation, before he could so much as pick up a chisel.

The Death had been especially long this year and the ice had draped itself over everything, layer on layer, during the cold months. A particularly large build-up had caused a section of the mine’s spiral access track to shear away, leaving the rock beneath exposed and saving him many days of surveying and excavating. The next stage, the cutting and hauling of the block, had been more dangerous due to the sheer rock face; even now, powered down, the lifter unit gave off a smell like burned hair that showed how close it had come to failing on him. The motor housing ticked and creaked as it cooled in the sharp air. Then the wind gusted from the west and the giant pit behind him emitted the deep bass note that gave it its name.

The Groan’s call filled the tundra and drowned out everything for a few heartbeats, so he didn’t hear the skimmer at first. When the uneven pulsing chug of its engines finally made itself known, the heavy utility vehicle was almost upon him. He could see where it had kicked up a trail on the thawing track which wound its way from the hills to the east. The narrow road took in a half-circuit of the circular rim of the pit before ending near where Cale had set up his tools. The rust-red skimmer was bulky, old and jury-rigged, listing under the weight of its cargo, a haze of compressed air distorting the underside.

Cale dropped his heavy gauntlets on the workbench and shrugged out of his booster harness. He shifted and stretched in his protective suit. The sweat from the work was still lukewarm between his shoulder blades, though his ears and cheeks were raw from the cold and his breath misted the air. There was a moment of dislocation, until he caught up with himself, remembering that the landslip had saved him those two weeks – normally the first supply run of the year would find him deep in piles of excavated mud. A reminder of last year’s dig lay nearby next to the broken security fence: the engine he’d cobbled together from scavenged parts, when the permafrost had been so hard he’d had to jet-blast it just to be able to break the surface.

The skimmer – grav-trailer bobbing along behind like a leashed larg – pulled up at the edge of the apron. There was a mechanical sigh, followed by the grateful ticking of cooling metal as the skimmer powered down and the cab door popped open. The old man from the village jumped down, the vehicle barely shifting on its air cushion. He wriggled his shoulders inside the big oilskin jacket. He wore a thick cap with flaps that hung down over his stubbled, hollow cheeks. He caught Cale’s eye, a mitten rising in greeting. Cale returned the gesture and went to meet him.

They rode the short distance back to the hangars in the skimmer. Once there, Aulk was all business. Cale could see the Groan’s shadow in the fisherman’s hesitant step and furtive glances over his shoulder. The place had a reputation amongst the locals, and because of it he had to pay well over the odds for these supply drops; only cash and the occasional bottle of rakk kept the old man to his word, making the seasonal journey from the village over the hills. Aulk was not unfriendly but always eager to be gone from this eerie place and him, the strange foreigner who lived with the ghosts.

Cale had been alone for so long he found he’d lost the knack for conversation, so the talk was minimal as they worked.

‘Lift that, on three.’

‘Pass that down.’

‘Careful there.’

For the first time in a while he was conscious of how he must look: his hair and beard unkempt and matted after the months of dark isolation, and now mussed with sweat. The mad hermit and his rocks. Just another reason to stay away.

The unloading took longer than usual and he could see Aulk checking Ras’s position in the sky every so often. The first drop after the dark months was always the biggest – power cells had run low; fish, meat and vegetables were distant memories. For the last month he’d been on reclaimed military field rations that all tasted identical – fine as long as you didn’t look too closely. He was heartily sick of them.

Another, second lifter-field unit, the twin of the one he’d used that morning, helped shift the heaviest crates into the open hangar, then Aulk let him haul the rest. Cale towered over the village man and his thick arms could carry twice the load. He noticed Aulk’s limp had got worse during the Death, and he was even less help than usual. The old man shuffled about, offering the odd grunt of encouragement, occasionally holding out a steadying hand. Cale found himself sweating again and a tired old voice at the back of his mind told him he should start exercising. As usual, he ignored it.

By the tail end of the afternoon all the crates were piled up in the hangar he used for storage. The unladen skimmer floated a half-metre higher off the ground; Aulk had powered down the trailer and stowed it away. Cale leaned on some crates to catch his breath, feeling the wetness that had spread from his lower back. Neither man spoke for several minutes. Aulk cleared his throat as if to start talking but hesitated; Cale saw him looking over at the Faces, all nine of them lined up on the empty concrete square, their frozen expressions facing north.

He wondered if there was some significance to it, some unthinking reason why he’d arranged them that way. The carved blocks of granite charted his time here, one for every year. With each one he’d got better as he’d learned: how to visualise the shape inside the block, how to chip and wedge and scrub and polish until it emerged. Always the same subject, a woman’s rounded face with shoulder-length hair and a half-smile playing over her lips. Every year, he got a little closer to her.

Aulk shuffled and Cale knew he was about to ask about the Faces, but a gust of wind came barrelling over the plain, passing over the open mouth of the Groan and making it sing like the top of an enormous bottle. The low, mournful note vibrated through the ground and the air all at once, pounding eardrums and shaking bones. Aulk’s eyes widened, his jaw slack. He took a step towards the skimmer as though something invisible had pushed him, gripped the cab’s handle, but did not open it, standing stock-still as the noise died away.

Cale stood up straight and stretched as if he’d not seen anything. He gestured at the entrance to his home. ‘Come on. Let’s go have a drink.’

* * *

The two men sat at Cale’s only table nursing earthenware cups of hot rakk. Aulk looked a little calmer indoors. Cale watched him take regular, rapid slurps, the weathered old face twisting into a grimace of pleasure with each. He brushed the base of his own cup back and forth over the pitted wood, painting it with a tiny spill of liquor, waiting for the right time to break the silence.

Aulk smacked his lips and caught Cale’s eye. A minute nod of the head, acknowledging the quality of the drink.

‘Good?’ Cale asked.

The fisherman nodded. ‘Good.’ He clasped the cup between his palms to soak up the heat. ‘Now I know how you can stand living in this Sky-forsaken place.’

‘I like the quiet,’ said Cale. He put his drink on the table between them and sat back in his chair. ‘The stone is good.’

Aulk made a sucking noise between his teeth. ‘Stone don’t keep a man warm. Can’t eat or drink stone. I wouldn’t live out here for all the money in the world.’

‘I have what I need.’

Aulk’s brow remained furrowed. ‘Bad place. Can’t be good for a man to be out here this long.’ He looked Cale over with a critical eye, like he was searching for some outward sign of something wrong.

Cale shook his head. ‘It’s an old mine. Nothing more.’

‘You’ve heard the stories.’ Aulk took another battery of sips.

Cale had, many times over the years, and never the same tale twice. It had been a war, some said, that chased the miners away; others said a plague. A couple of years before, Aulk had stayed for one more cup than usual and had spun a yarn of his own about the miners being driven mad. It was the Lattice, he’d said: out here, alone in the barren tundra, they couldn’t bear those dark claws blocking out the lights in the night sky and dragging great shadows over the land during the day. With nothing but flat, iron earth beyond the town limits stretching to the end of the world, the horror of the thing was too much to bear. One night, as one, they’d all risen and walked to the lip of the Groan, tossing themselves in without so much as a scream. They were still there, he’d slurred, glassy eyes staring up through the dark waters, waiting.

Waiting for what, Cale had asked, but the old man shook his head and refused to go on.

That time was vivid in his mind as he watched the fisherman finish his rakk. It always came back to the Lattice, in the end, wherever you went. Raised in the Home Peninsula and a product of the best academies his father’s rank could afford, Cale could count himself as an educated man, but even he felt an ominous stirring whenever he looked up, day or night, to see that huge, complex intertwining shape hanging there. It was the sheer scale of the thing that brought on a kind of vertigo, giving form to the immense distance between the ground and the outer shell of the world, the roof of all existence.

Aime had been the only one who’d been willing to talk about it. Her guess was that it was a leftover from the ones who’d come before, something even the Ruin couldn’t obliterate. It was a monument of a forgotten people, she’d said, meant to inspire wonder, not fear.

For an instant the smell of her hair against his face was everything.

Rising, he gathered the mugs and went to refill them from the kettle. ‘I’ve heard some of the stories,’ he said. ‘Do you ever wonder what it was for?’

‘The pit? Why would I?’ Aulk accepted the full mug. ‘Thanks.’

‘Not much in the way of minerals around here. Certainly nothing worth something so large. The mine, this whole town. I wonder what they were digging for.’ Cale had pondered this many times, in the quiet months when the cold kept activity to a minimum. Why scoop a cone two kilometres across and one deep into the barren steppe?

It wasn’t just Aulk who was reluctant to discuss the Groan – he’d never heard a straight answer from anyone and now he rarely brought it up. It was difficult enough getting people to talk to him, like he’d been tarnished by the place.

‘I catch fish,’ said Aulk. ‘I try not to think about it. Place gives me the shivers.’ He shrugged. ‘Who the hell knows?’

Leave it alone, is what you want to say, Cale thought. It was difficult to look past the stories your grandam told you.

The fisherman launched into his freshened mug of the fiery amber spirit. Cale filled his own and returned to the table. There was something in it, he had to admit. Sometimes, when Ras began to lower in the sky, he’d find himself hurrying to get indoors to light and warmth and shut out the wind howling over the broken old buildings. That sound: nothing more than a meeting of wind and geography, the rational part of him said, though even after all these years it could still shake him awake with hackles raised.

At least I have peace, he thought.

He looked up at the ribbed ceiling of his home. The long, arched metal structure looked like it had once housed mining trucks or even light aircraft: there was a hint of grease that time had never fully scrubbed away. Its shape had been proof against the weight of built-up ice, though thawing the coffin of frozen water around it had taken many days when he’d first arrived. It was comfortable now with the windows sealed and the concrete floors sheathed in thick carpet. The wooden partitions that made up rooms cut down the echoes and he’d filled every bit of empty wall with old books and older landscape pictures – the only reminders of the world he’d left behind – and added lights to all the rooms, staving off some of the oppression of the dark months.

Cale let the silence stretch, content to listen to the ticking of the old chrono in the corner. It, and the dark wood chairs they sat in, had come from the ruins of an administration office in the town – he was careful never to mention this. There were book piles dotted around on tables and chairs, empty bottles, unwashed plates in the sink, making him wish he’d thought to tidy some of it away.

The place must reek of me, he thought.

He hated the Death that kept him shut indoors and away from working on the Faces, his sole vocation robbed by swirling winds that cut to the bone. Nothing to do but drink, read and try over and over to get a tune out of the old bandothal on the wall. There were faded patches on the fretboard where Bowden’s hands had marked the wood and he could still hear how it had sung under his deft, young fingers. He wondered for the thousandth time why the one thing he’d brought to remind him of his son was something he could not hope to master – the stubborn strings only whined in his thick hands. Every time he tried to play only reminded him of that last time, when words had cut the air with the heft of resentment. The memory of their parting always came on fast and had him abandoning the instrument for a bottle of something strong and dark as remorse threatened to swallow him down. After the second bottle, he’d shout his questions to the empty room, but the stubborn bandothal gave him no answers. The pale light of the Wake was always a blessed relief.

There was little reason to worry about how the place smelled, he realised, coming back to himself: Aulk’s own powerful odour of fish and engine grease pervaded the air. The warmth of the room and the drink had relaxed the fisherman, now resting his feet on the open rakk crate as he contemplated the ribs of the vault above him between longer pulls on his steaming mug. Cale leaned back into his own chair and savoured the feel of the rakk’s sweet-burning vapours jumping up his nose and down his throat before spreading heat to his fingertips and toes.

‘How are things in Endeldam?’ he asked.

‘Oh, same, same you know.’ Aulk took a gulp, his brow creasing. ‘Long Death this year. Ice was thick. Fish were slow to come back.’

‘And now?’

‘Buggers turned up, so no bother. But, ah… there’s this new Factor in town, and a new official means more…’ he rubbed a finger and thumb together. ‘Always more tax.’

Cale nodded. ‘And… your new wife?’

Aulk brightened, easing his shoulders back and giving a contented sigh. ‘Fat and warm. Soft-like, eh?’ He winked. ‘She’s, ah…’ Aulk held cupped hands out in front of his belly.

‘Already?’

‘Of course she is!’ A twinkle in the old eyes. ‘For fishers the Death is mighty dull, unless you like drilling holes in the ice. So, instead, we get drunk and… drill holes.’ He hooted and slapped his knee, then doubled over with a rattling fit of coughs. ‘Bad Death, though. Too long,’ he said, cuffing moisture from his eyes.

There was silence for a while as Cale made another trip to the steaming kettle to refill their mugs.

‘Ah.’ Aulk straightened like he’d just remembered something important. ‘Got… gots ’mink for…’ He rummaged through his numerous pockets, then his small backpack, finally finding what he was looking for with a satisfied grunt. ‘Came just last week, first ship to break through.’ He handed the object over, a light brown paper package that had paled and stiffened at the edges. It was still sealed.

Cale turned it over in his hands, examining it. His name was written on it in thick handwriting he recognised. He gave it an experimental squeeze. The thick paper crunched under his big fingers – there seemed to be something rigid inside.

‘Would’ve brought it sooner but, well…’ Aulk let the words hang.

Cale ripped open one end of the package and carefully tipped out the contents – a metal cylinder rattled on the table and came to rest. He picked it up – heavy, dull gunmetal, flat-ended and as long as his forearm. At each end was a stud, one blue, the other black. He held it level in front of his face.

‘What is it?’ The fisherman’s eyes were locked on the cylinder.

‘A message capsule,’ he replied. ‘My… friend in Keln uses them. Old tech. An affectation of his.’ Cale pressed the blue stud and there was a click, followed by an electronic chirp. A flat, glowing rectangle sprung into existence, then flickered out again. He slapped the end of the cylinder against his palm and the screen popped back to life, filled with lines of blue code. Through the translucent display, Aulk’s eyebrows disappeared under his hat.

‘Old, you say? Makes radio relay look like carving on wood.’

‘Not many of them left now.’

Then the screen flickered again. A man’s face appeared, staring directly at the camera. It was fleshy, round and completely bald.

Aulk snorted. ‘Soft city man, I see that.’

‘Brabant is his name. And you’d be surprised.’

‘Looks well fed.’

‘He arranges the payments for my supplies.’

The fisherman went quiet.

Cale waited for Brabant to begin. His friend’s heavy jowls always made him look sombre, but there seemed to be something else this time – perhaps a tightness around his eyes or a rigid jut to his jaw.

‘Cale,’ fuzzed the voice, coming at them as if from the other end of a long room. ‘Brabant here. Well… you know that.’ He looked down, seemed to be toying with something.

Disquiet seeded Cale’s belly.

‘Look, I’ll come straight out with it, it’s bad news. Bowden’s hurt. I mean, he’s been hurt. I got a… I got contacted by the Army. I know you parted on bad terms but… well.’ Brabant passed a hand over his face and rubbed an eye. ‘Skies, I wish you were near a relay station, Cale. I don’t even know if this is going to reach you…’ He took a deep breath. ‘Details are sketchy – you remember what the military’s like. Some police action down south. Something happened; he did something bad before he was injured. And now he’s in a lot of trouble.’

The world beyond the screen dropped away until there was nothing in the universe but that glowing square and sad eyes in a tired face. There was a dark hole above Cale’s breastbone that felt like it might suck everything into itself. He forced a halting breath.

‘He’s been sent to Sessarmin, the sanatorium,’ continued the recording. Brabant’s eyes stared straight at the camera. ‘You know what that means. How bad it had to have been to get him sent to… that place.’ He looked away. ‘They say he’s critical, but stable. But he’s not waking up, Cale.’

The hole grew, swallowing him whole until only the pounding in his ears reminded him that he was alive, sitting with shoulders hunched, eyes unblinking and starting to water.

‘That’s it. I’m really sorry to have to tell you this. I don’t know if this message will reach you in time, but… well, there you have it. Go well, old friend. Get in touch.’ The screen flicked back to code.

Without pausing Cale hit the blue stud and listened to the message again. On the other side of the world, Aulk shifted in his chair and cleared his throat.

It was a mistake – another plea from Brabant to come back to the world, that was all.

The words came again, each one a bullet impact. Cale’s disbelief died a little more with every shot, replaced by a creeping, hollow horror.

He’s not waking up. The words were an ice burn.

He hit the black stud and the screen flicked off. With slow, deliberate care, like it might shatter, he placed the cylinder on the table. He leaned back, closed his eyes and let his head droop with a long, rasping breath.

Oh, what the hell, he thought. What the hell.

A lifetime ran past, a flurry of memory, scenes jumping out of the flow but disappearing before he could focus.

A small, soft hand holding his weathered fingers.

Aime walking away, smiling over her shoulder.

His son’s face twisted in anger, looking too much like his own.

His hand whipped the table with a gunshot slap; rakk spilled; the cylinder rolled off and thunked on the carpet. Aulk jerked back, his eyes wide.

Cale inhaled through his nose, then stuttered the breath out past his teeth. He was standing, he realised. Looking at Aulk’s huddled form, he realised just how much smaller and skinnier the other man was – in that moment he looked almost childlike.

Slowly, he held up his hands. ‘I’m sorry. Bad news. Very bad news.’

The fisherman knocked the table with his knee as he stood. He downed the dregs of his rakk. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I’ll go. You need time to yourself. Terrible news.’ He nodded, agreeing with himself. ‘I’ll be back in a couple of months, but if there’s—’

‘Wait,’ said Cale. The sucking hole was still there but he held himself from its edge by force of will. His hands had stopped shaking, and he knew what needed to be done.

‘Give me a few minutes,’ he said. ‘I’m going to need a ride.’

i. Karume

The Major was still asleep when she got up to make breakfast. Kelbee moved slowly, carefully, as she did every morning, not wanting to wake him. The rough tiles were cold underfoot as she drew a thin robe about her shoulders. She shivered as she searched for her slippers at the foot of the bed, but they were not where they should have been. Maybe he’d knocked them into a corner of the room. He’d come home late and she’d had to help him stagger to the bedroom, had to pull off his high boots after he collapsed onto the bed.

Kelbee gave up on her slippers, padding barefoot along the short hallway that joined their bedroom to the kitchen and lounge of the apartment. She paused to greet the Seeker, bowing deep to the portrait set on the otherwise plain wall reserved for it. As she straightened she spotted a fine layer of dust on the frame and felt a twinge of worry that someone might see it. She flicked a furtive finger across the polished wood, thankful that he’d been too drunk to notice last night.

The lined flooring in the kitchen felt clammy, like the skin of a fowl. The district’s power was still off at this early hour but the seals on the cold cabinet were in good repair and there was no smell of rot as she reached in. Kelbee took out a silver tarn, three fingers wide and as long as her hand, feeling a few delicate scales flake off on to the floor as she moved it to the counter.

With a small, sharp knife she cut the barbed fins away, and with quick, practised strokes scaled the fish into the sink. The dawn was coming, the faint light peering through the window in front of her as she worked, glinting off the scales in the basin.

Kelbee turned the tap to rinse the smooth fish and the pipes gave out a chopping groan. Startled, she shut off the water and listened for any sound of him stirring. She waited, tensed like a bird on a branch, but there was nothing; the apartment was still, save for the trickle of water down the drain.

Exhaling, she continued, drawing her knife along the tarn’s belly line from throat to tail. She used her thumbs to ease its silky guts into a bowl, then covered the quivering red mass with paper and set it aside for the end of the week when she’d make fish sauce. The Major liked her fish sauce, as long as the smell from the rendering was gone by the time he got home. She knew he liked it because he grunted when he ate it – a single grunt was high praise. The commonplace merited only silence. He only spoke aloud when the food was not to his liking and she remembered both times that had happened.

Two more cuts of the knife, running along both sides of the backbone, then she peeled the fillets away from the ribs, leaving the spine gaping on the board like a trap. She scooped the tender cheeks from the head before dropping the carcass into the waste bin under the counter, which let out a burst of cloying stink as the lid was lifted. The glue-makers only called every two weeks and she knew she’d have to burn more of her precious stock of incense to cover the smell until they came.

Kelbee took a pair of tweezers and set to plucking out a few stubborn, bristle-like bones from the fillets. Ras was up over the horizon now, hidden behind tendrils of low mist so she could look directly at it without having to squint or turn away. As she worked, it rose further until it broke free of the mist and passed behind the enormous edifice of the Tower, just two klicks from their small apartment, casting its shadow over her. She set the fillets down in the sink, rested her palms on the smooth ceramic lip and watched Ras’s bright corona haze the edges of the giant pyramid.

This was her time, a moment for herself every morning. When Ras emerged, she would continue with her day, but for these few minutes she could just stop and stare at the quiet city. It was so still she could pretend it was a model, perfect and serene under a glass case, like the one in the Unity Museum. Over there were the tall trees that bordered a municipal park, where citizens could take the air and which she crossed every morning on the way to work. Apartment buildings just like this one stood in neat, numbered rows, marching out from the centre of the city like the spokes of a giant wheel with the Tower at its hub. If she were to just crane her neck to the right she would make out the square charcoal bulk of the building where she worked; she didn’t, leaving the smell of bodies working close and the heavy chatter of sewing engines for later, when she could no longer avoid it. This time, now, was for her.

Every day, for these quiet turns of the dial, she could stop and remember how it felt that first day in Karume. The first time she’d seen a skimmer humming along the street on a cushion of hazy air, she’d stared at it open-mouthed, a dumbstruck country girl. Then the terrifying bulk of the Tower, taller than anything she’d ever imagined; a pyramid that seemed to join heaven and earth. Even after years of living in its shadow, she still marvelled at the madness of its scale. Reaching out, she ran a finger down the pane of glass, as if she might feel the hundreds of floors and balconies of the monolith as rough bumps under her fingertip like the scales of the silver tarn.

Ras emerged from behind the Tower – the moment was over. The light was piercing in the clear morning air, so she lowered the blind partway, and, as she did, felt the dull ache of her collarbone. She rubbed at the bruise, remembering. The Major’s breath had been rank with drink and he’d been asleep in minutes. Later, he’d woken, fingers grasping and insistent.

She patted the fillets dry with a cloth so the oil in the pan wouldn’t spit and wake him. She noticed a red light blinking on the rice steamer and knew the power had come on. This was a good thing: with fewer pans to wash she wouldn’t have to rush to work.

And, said a small voice at the back of her head, you might have a few more moments with him.

Her heart hammered in her breast and she wrestled the thought away – too dangerous even to think about it here, she couldn’t risk so much as the hint of a smile or a blush, so she distracted herself by adding rice and water to the grey cylinder and set it to steam, then rubbed salt into the fish, spreading it with her fingers. When it was time, she opened the top of the steamer and laid the fillets over the top, setting the timer, then busied herself with scrubbing down the countertop and hunting the floor for the last few rogue scales. Her breathing slowed and the panic flowed away.

Just thoughts, she told herself. No one could know. She noticed the chipboard door of one of the cupboards had started to warp with age and moisture, then the steamer drew her attention with its soft buzz. Under the hood the fish had lost its translucency and become firm. She tipped the whole lot, rice and fish, into a large, glazed serving bowl and mixed it together, the fish flaking just as she’d hoped it would.

She heard him move as he rose and though she’d heard the same sound every day for six years it made her breath catch in her throat. She forced herself not to pause, adding a pinch of smoked spice, some salt and a few drops of dark sauce to the mixture. He was in the shower now; she could hear the water splashing and the rasp of him clearing his nostrils into the drain.

She filled two bowls with rice and fish and touched the panel to turn on the strip lights in the living area, glad she’d had the presence of mind to set the table last night. She set both steaming bowls out and took one of the chairs to wait for him, her gaze lowered.

The Major came striding into the room and she pulled her robe tighter. He was clean-shaven and dressed in his uniform, save for his boots and hat, which she’d already placed by the door. He joined her at the table and set about his food without a word. He didn’t bother to look at her, shovelling rice into his mouth, smacking as he chewed. A snort, then he went quiet. Kelbee’s shoulders froze. Looking up, she saw him chewing slowly, his brow creased. He spat the mouthful out onto the floor.

‘This is terrible.’ He went to put the bowl down but missed, catching the edge of the table. Kelbee watched it as if in slow motion, tipping, spinning, finally hitting the floor with a crash that spilled the white-grey mixture over the tiles.

He rose. She inhaled.

He walked past her and began pulling on his boots. While his back was turned she took a spoonful from her own bowl and sampled it with care. There it was – a few bullet-like grains that clustered around the chunks of soft fish – the steamer must have another leak. She’d have to find it and repair it before she left and clean up the mess. There would be no early walk today.

She heard him straighten behind her and rose to face him. He’d put on his peaked officer’s hat.

‘No more damn fish,’ he grunted. ‘Get some meat in.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Kelbee bowed her head.

For the first time that morning, for only an instant, their eyes met. He was not much older than her, still in his thirties. His face was young, severe but unmarked except for dark shadows under his eyes. His body was trim in the uniform, fit and lean. His hands were slim and strong. His eyes were bleary today, but ordinarily were piercing, as if seeking out threats; he looked like a tree branch held back by brambles, ready to snap forwards with terrifying swiftness.

He would have been handsome, she thought, if it weren’t for the wide mouth, too big for his face. She’d fallen in love when she’d been given to him: the tall soldier in his crisp uniform whose name she’d heard once when the Teller read it out and vows were exchanged, then never again. It had been so long that she could no longer recall it; he was the Major, always, and she’d not had the strength or the will to climb over that wall.

He broke the contact, looking away.

‘I’ll be home late again,’ he said, adjusting his cap. He looked at the mess on the floor, then back at her. He looked for a moment like he might apologise, but it passed. ‘Work hard,’ he mumbled. He keyed the door and it slid open with the squeak of rubber on rubber, then he was gone.

A strand of her blue-black hair came loose over her eyes and she brushed it back behind her ear. She noticed four small red crescents in the meat of her palm where her nails had dug into the flesh.

Gloves today, she decided, and maybe a scarf.

* * *

Her morning commute took her through a tight warren of alleys at the base of the apartment block and out onto a thoroughfare. A few other women were making their way to work; at this time of the morning, with their eyes downcast and with purposeful strides, they could be going nowhere else. She must look the same to them, with her hat pulled low over her eyes and her collar turned up against the wind that blew down the long street, ruffling the gaudy red and blue Quincentennial banners. In this middle-ranked district there was little street traffic at this time of day, apart from the occasional skimmer making a delivery. One was backing out of an alley, beeping as it reversed, a shopkeeper waving the driver out as a boy in trousers too short for him stacked the boxes that had been delivered. One split in his hands, sending dark berries scurrying over the pavement. Kelbee crossed to the other side to avoid the mess as voices rose.

The words of the Seeker droned from the screens mounted on high posts spaced evenly along the street, as they did every day. The muffled utterances echoed off the shop fronts and windows, following her steps. The city was stretching, coming to life as she passed. At the end of the street she came to a checkpoint where her pass was scanned. She felt the usual jab of fear in her heart as the policeman looked her over, then kept her relief hidden as he waved her through, turning to the next person in line.

Beyond the barrier lay the park. Kelbee followed the white gravel path that cut through the grass, heading towards a row of skeletal trees on the far side. In the centre of the park was a wide gravel circle. She joined others who milled about the feet of a Teller, the morning ritual already begun. The platform on which he stood, red-robed and straight-backed, was at head-height to the assembled crowd and set before the gleaming statue of the Seeker, gazing with beatific eyes over the sweep of the park and the city blocks that fenced it. The Teller was mid-flow when she edged in.

‘…cast down the ignominy of the old world, the corrupt, the decadent, the vile. He built the Walls that keep us, wrote the Principles that bind us and set us on the path to the exalted Inner Victory. For who was saved when the waves came? Who emerged from the broken world, ready to sow anew? For this, we give everlasting thanks to Him, our Eternal Leader.’

A speckling of mutters replied, tired voices repeating their daily catechism. The Teller’s eyes flashed, and the words of thanks were repeated, this time with greater gusto. By his side a Factor stood mute, eyes attentive, one hand on the pistol at his hip.

‘Bow, for Temperance,’ the Teller intoned. ‘For Vigilance, Modesty, Abstinence, Fortitude, Restraint, Obeisance, Fear and Love. They shape the lives we lead in His name.’

For each Principle of Inner Victory, they bowed to the likeness of the Seeker, the group rippling like grass, the timing ingrained. Kelbee, though a country child, knew the rituals well enough after six years in the capital. She also knew every bow was watched for appropriate veneration.

She waited her turn, then stepped forward to press her fingertips against the golden foot, the metal polished by thousands of daily caresses. The great eyes, high above, ignored them all.

Respects paid, she continued on her way. She was behind, and work was to start soon, so she picked up the pace though her bag rubbed against the bruise on her collarbone, restricting her. She passed through the border of trees, noticing that a few were beginning to bud even though the air still bit at her cheeks. As the Death faded into the Wake the mornings were brightening, the skies clearing; she hoped the birds would return soon to rustle at the branches, filling the grey air with their songs. No branch had been spared decoration for the upcoming celebrations, blue and red garlands strung between them like the web of a great colourful raknud. The time away from work she was looking forward to, but the parades… The parades were exhausting, mandatory affairs for a military wife.

Fortitude, she thought to herself. It’s your duty.

The wind cut across her face as she emerged onto the park-girdling street, making her hunch her shoulders against the chill. When she reached the charcoal-grey lump where she worked, her heart sank: the queue stretched almost to the far corner of the building. Several floors above, the klaxon would be about to sound the start of the working day and if she was seen to be missing there would be consequences.

She made her way past blank morning faces until she reached the tail, and there he was, waiting. He saw her and a brief smile flashed over his lips – a mere flicker of clouds parting to anyone but her. She didn’t dare return it as she joined the queue behind him and a little to his left, so she could see the nape of his neck where it dipped beneath his collar.

Nebn’s head turned a fraction. ‘Morning,’ he murmured. A simple greeting between acquaintances. A pounding of drums.

‘Yes,’ she replied, her ears thick with hot air. She turned her head, embarrassed she couldn’t think of anything better. When she looked back he’d turned away again.

The minutes dragged on, and for all the closeness to him stole her thoughts away there was a nagging in the back of her skull that every person in the queue in front of her was making her tardier. After what felt like an age, they shuffled into the foyer and waited to pile into one of the big elevators. When the car came, they managed to stand side by side as it rose through the building, watching the glowing floor numbers count up. Her fingers were a breath away from his, the air between them. Behind them, a man snorted. A woman was chatting to a friend about the upcoming parades and the feast days. Kelbee felt, more than saw, Nebn’s face turn towards her a fraction.

‘How was the park this morning?’ he asked. ‘Pretty, eh?’

She nodded back and smiled. He smelled of woodsmoke and soap. He was tall, the tallest in the elevator, though he stooped. She allowed herself a glance: liquid-bright eyes, a sharp chin and cheekbones softened by crow’s feet and crescent dimples around his mouth that formed deep pits when he smiled, which was often. His lips were thin and firm – just that darting look brought a flash of memory, of softness and the taste of mint on her tongue. His hands, held by his side, were strong and soft. Before she could allow herself to remember how they’d felt on her skin she forced herself to look away, anywhere else.

He’d been working on a faulty heating unit on the day she’d first seen him. The elements often broke and turned the chilly factory floor unbearable – the number of accidents from fumbled shears were always worse during the Death. Contracted workmen were transient visitors and didn’t talk to the women in the factory unless it was to order them out of the way.

Kelbee had been carrying a heavy bobbin from the storeroom down a narrow side corridor when it spilled from her numbed hands and hit the floor with a metal clunk, spinning into an overalled, helmeted workman, unspooling as it went. She’d expected at the very least jeering, or even a call to the monitors to reprimand her for her clumsiness. Instead, he’d been there with his kind face and gentle words. He’d not said much but had helped her gather up the thread before giving her a parting smile and returning to his task. It was only later that she realised they were the first words she’d had from a man in years that hadn’t been an order or a grunt of disapproval.

She’d spied him coming from another side of the park the following day, converging on the Seeker’s idol for morning worship just as she was. As she’d mouthed along with the Teller, she’d shocked herself by imagining what it would be like to walk alongside him, running the conversation over and over in her head, playing both parts. After, she’d even sped up to catch him, but when she was almost in earshot her nerve went and she ended up hanging back.

The next day, he’d waited for her at the edge of the park and greeted her with deference, even reserve, but behind the words were smiles that licked her like a shock of lightning. Then, later, in a place hidden away from prying eyes, the outlines of his body had melded with hers as they broke every rule she’d ever known.

The elevator continued up, dropping off people until it was empty but for the two of them and an older man leaning against the back wall, looking for all the world like he was still asleep. Kelbee felt the silence like a thick blanket.

‘I love the Wake. It’s like everything’s… swept clean,’ she murmured, wishing she had a better way of saying it.

Nebn nodded back with a small smile, and she cursed her awkwardness. Then it was his floor and he said goodbye before stepping out. The older man started awake and rushed past the closing doors, bumping into Nebn as he turned back. He mouthed the word, ‘Goodbye,’ at her; their eyes met and she felt a flutter just above her stomach.

When the doors closed she realised her cheeks were burning and her smile reached the corners of her face.

* * *

The factory floor was already filled with clicking and whirring as the garment-makers began their day. A few were still drifting back from the commons area and heading for their workstations. A glance at the chrono told Kelbee she’d missed the pre-work salutation and exercises, but there were no monitors nearby so she slipped in behind a shuffling group of women and did her best to blend in. At her station, keeping her face down to hide her rapid breathing, she shrugged off her coat but left her scarf on – she didn’t much feel like being the subject of gossip this morning.

Like the other workers she wore a light blue shirt and trousers, and she’d pulled her hair back into a tight bun that slipped easily under the hairnet. She pulled on a white cloth facemask and climbed onto the high chair bolted to the floor behind a clunky, rust-stained sewing engine. Strands of black and brown cotton hung from the ceiling, joining the machine to a narrow metal frame suspended overhead. This ran along to a cluster of bobbins dangling in the centre of the six sewing stations, supplying them all with thread like puppets in an oversized koktu show. There were four sewing clusters like this one on the floor, and the air was alive with the dull rattle of chattering industry.

From a stacked trolley by her side Kelbee pulled the topmost garment, a pair of rough-stitched trousers. Setting her head down and her feet on the pedals, she began to hem with smooth, practised passes. The needle before her whirred up and down, leaving a neat line of stitching across the rough brown fabric.

The other five women in her cluster were doing the same, heads bent and eyes intent on their work. As Kelbee worked, the pile on her right shrank and the one on her left grew. When it became ungainly, she stopped and hefted it over to a wheeled cage at the edge of the circle of machines; when that was full, a porter in red overalls appeared to push it to the next stage in the production line. There was no talking, only the chatter of the machines, the rumble of the bobbins and, faint under everything else, the tinny echo of State music. It was there to inspire them, they’d been told.

On most days Kelbee could go into a trance-like state where her hands and eyes and feet all worked in unison without the need for much guidance, but not today. Little things kept distracting her, like a fly darting past her eyeline, or a particular note in the music that grated on her. Her collarbone rubbed raw against the rough material of her shirt and she could not get comfortable on the stool.