Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

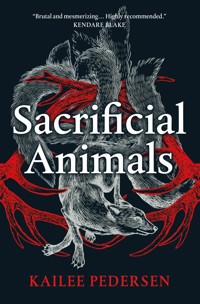

Two brothers return to their family home to care for their dying father, only to find the ghosts of their pasts are restless and hungry for blood in this gothic horror, perfect for fans of Hereditary and readers of Stephen Graham Jones. When their father calls them to tell them he is dying, Nick and Joshua rush back to their Nebraskan childhood home, Stag's Crossing, hoping for a deathbed reconciliation with the man who raised them. But their return sparks memories of their childhood, and their father—Carlyle—a ruthless, violent racist who ruled Stag's Crossing with an iron fist and disowned Joshua for marrying a woman of Asian descent. Very quickly, the family find themselves falling into familiar patterns. Joshua and his father renew their tight bonds. As his long-buried memories of a youthful romance with another boy resurface, Nick finds himself ostracised and growing closer to Emilia, his brother's enigmatic wife. But something else has arrived at Stag's Crossing, a presence out for revenge, and Nick, Joshua and Carlyle, who have traded in blood, dirt and violence for so long, are about to face a reckoning like no other. Inspired by Kailee Pedersen's own journey being adopted from Nanning, China in 1996 and growing up on a farm in Nebraska, this rich and atmospheric supernatural horror debut draws on ancient Chinese mythology to explore the violent legacy of inherited trauma and the total collapse of a family in its wake.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Copyright

Title Page

Leave us a Review

I. Then

II. Now

III. Then

IV. Now

V. Then

VI. Now

VII. Then

VIII. Now

IX. Then

X. Now

XI. Then

XII. Now

XIII. Then

XIV. Now

XV. Then

XVI. Now

XVII. Then

XVIII. Now

XIX. Then

XX. Now

XXI. Then

XXII. Now

XXIII. Then

XXIV. Now

XXV. Then

XXVI. Now

XXVII. Then

XXVIII. Now

XXIX. Then

XXX. Now

XXXI. Then

XXXII. Now

XXXIII. Then

XXXIV. Now

XXXV. Then

XXXVI. Now

XXXVII. Then

XXXVIII. Now

XXXIX. Then

XL. Then & Now

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

“Terrific. An intricate exploration of familial implosion, a gothic horror delight that had me hooked from the first sentence.”

Irenosen Okojie, Betty Trask award winner and Shirley Jackson award-nominated author of Butterfly Fish and Speak Gigantular

“Kailee Pedersen explodes onto the scene with Sacrificial Animals! A weird, gorgeously written supernatural thriller about how the crimes of our fathers can cast dark and devastating shadows over innocent lives. Very highly recommended!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Cave 13 and The Dragon in Winter

“Sacrificial Animals is distinctly observant, and distinctly unsettling. It begins with one sort of menace and ends with another entirely, so that while the book barely leaves its little patch of acres, and the souls who occupy it hardly move an inch from the traumas that shaped them long ago, it leaves you with a feeling of immense distances traveled.”

Kevin Brockmeier, New York Times bestselling author of The Brief History of the Dead

“Sacrificial Animals is a bleeding wound of a book. Stark brutality is deceptively packaged in beautiful sentences.”

Verity M. Holloway, author of The Others of Edenwell

“Brutal and mesmerizing, Kailee Pedersen’s Sacrificial Animals drew me in immediately. Easily readable in one sitting, this enigmatic family saga is better savored to appreciate the rhythm of the language and the growing sense of unease. Highly recommended.”

Kendare Blake, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Three Dark Crowns

“Sacrificial Animals is a ritual exorcism of family trauma—brutal yet cleansing. Pedersen conjures up a religious nightmare of fathers and sons, which thrums inexorably towards its devastating conclusion. Written with the dirtrock mysticism of Annie Proulx and suffused with Chinese mythology, this book will rip your heart out for your own good.”

Noah Medlock, author of A Botanical Daughter

“Sacrificial Animals is an absolutely startling novel. Shot through with a rich vein of violence, toxic relationships, and a simmering undercurrent of folkloric magic, Kailee Pedersen’s hypnotic prose conjures Cormac McCarthy so deftly you might think she’d resurrected him.”

Ally Wilkes, Bram Stoker Award® finalist and author of Where the Dead Wait

“A delicately braided and unflinching tale of inherited family damage and revenge that walks a careful line between the realistic and the supernatural, crossing from one into the other before you—or the hapless characters—are fully aware. Sacrificial Animals reads like what might happen if Cormac McCarthy and Lafcadio Hearn were stuck waiting out a snowstorm in Nebraska and decided to collaborate.”

Brian Evenson, author of The Glassy, Burning Floor of Hell

“Kailee Pedersen employs the rich prose of early Cormac McCarthy, the bracingly vivid descriptive power of Willa Cather, and the doom-heavy fatefulness of Greek tragedy to create something very much her own: a deliciously gothic horror novel. The set-up is simple: an abusive father summons his two grown sons home for a deathbed reconciliation. But before they can bury the old man, the ghost of a crime from their collective past comes calling, seeking vengeance. Sacrificial Animals’ final thirty pages will leave you gasping.”

Scott Smith, New York Times Bestselling author of The Ruins

“Kailee Pedersen’s terse, tense, deeply unnerving debut novel mesmerized me from beginning to end. This is a young writer to watch!”

Dan Chaon, author of Sleepwalk

“An incandescent study of American masculinity with an unforgettable genre-busting twist.”

Alex Landragin, author of Crossings

SacrificialAnimals

Sacrificial Animals

Print edition ISBN: 9781803368740

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368757

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: August 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Kailee Pedersen 2024

Kailee Pedersen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

I. THEN

Moonlight slashes open the boy’s face like a luminous wound. He puts on his brother’s goose down jacket, still too large for him, but the spring cold is crisp and bitter and there will be nothing to warm him outside the house. Through the screen door he can see one of his father’s favorite greyhounds lying half-asleep in the tall grass. Westerly comes a sharp wind that wakes the animal and sets it running up the gravel road leading to the entrance of the family manse past the glass-eyed buck’s head welded to the curlicued front gates. The people from town call it Stag’s Crossing after this vulgar display of taxidermy. One thousand acres of rich loam atop the Ogallala Aquifer but only one man there calls himself master of the house with the ornate staircase and milk-white facade. Carlyle Morrow paterfamilias and patriarch. Tall and angular in a peculiar way his face marked by the heat and silt of his childhood in South Carolina. His eyes sharp and green as cut emerald his hair going an early gray. His gait slightly bent to one side like a limping animal though he is strong as any of the summer farmhands he hires to thresh the wheat and husk corn. He drives his white Ford into town every weekend to play pool and drink and stand at the bar and look out the window like he is scrying his own future.

Married only once: his wife French-Oklahoman, a heathen wildness in her gaze dead now for several years having given birth to a monstrous child that in its dying killed her in turn. At the funeral the pastor spoke of the two boys she had left behind though now that she is buried they have forgotten her entirely. Motherless as though Carlyle had cut them from his own flesh. As God made man from a fistful of dust.

Nicholas and Joshua he calls them, the younger and the elder. Whistles to them like a pair of hunting dogs. The older boy Joshua blond like corn silk and the younger one Nick walnut-colored in hair and eye. Like two young bucks they have jousted for dominance in their youthful and garish splendor though Joshua as heir apparent has always been the fated victor. With no women in the house they turn against each other easily with the characteristic cruelty of young boys bereft of civilization. Leaping over the shallow creek and racing through the woods south of the house one pursuing the other until there is no distinction between the courser and the game.

At thirteen Nick is whelped of mother’s milk, his walnut hair grown darker with age to a raw hazelnut. He goes out of the house with his father’s hunting rifle like an angel sent by God to do his killing work. Had he any sense he would have killed his father with it long ago but he has not. Patricide is the least of his concerns. His father says some beast has been laying its tracks around the house and is in need of a good killing so he paces outside the house that night with the gun to reestablish man’s dominion over the animals like his father’s dominion over his children. Carlyle possessing like his own father did before him a violence keen and beautiful as the silver curve of a fishhook. Nick gentler and perhaps even fawn-like, strange somehow. Fashioned in the image of his mother—even more than that he is the last evidence of her presence at Stag’s Crossing, the singular inheritor of her most feminine and sibylline qualities that fill his father with unease.

Having come round the eastern side of the house and found nothing he joins his father in the driveway where Carlyle stands surveying his vast demesne. The Ford idling out front like a waiting hearse.

Didn’t see anything out back, Nick says.

Then look harder, Carlyle says. He points to tracks in the soft soil. Nick squints. Whatever animal has left these behind is swift of foot and light upon the earth. One of his father’s greyhounds comes up behind him, sniffing his hands. He recalls their restlessness, their alacrity. Drawn tight as a bowstring they might at one moment sleep soundlessly in the driveway as peaceful as children only to awaken and overtake a hare with a perfect, savage brutality.

Might be one of the dogs, Nick says.

You ought to know better than that, Carlyle says, lightly cuffing Nick’s ear. Nick sways on his feet; he is lucky it is not a harder blow. Look at the toes.

Fox, Nick says, at last. Probably here for our chickens.

His father nods.

Should I get Joshua? Nick asks.

No, Carlyle says. He draws his heel over the track, burying it in a furrow of upturned dirt. As though its very existence offends him. Joshua’s going to college in a few months. You need to learn to handle things without him.

I can handle things without him.

No, you can’t, Carlyle says. Get in the car. I’m teaching you.

A few of the greyhounds have gathered round them now, crowding into the back of the truck. Nick climbs into the passenger’s seat and his father slowly pulls them out onto the main road, past the gates of Stag’s Crossing.

Only a short drive, Carlyle says. Just need to get to the other side of the woods. We’ll make a stealthy approach.

It’s late.

Not for foxes.

After negotiating the turn west of the house that points toward the woods, Carlyle says, You ever seen a foxhunt?

In a book I read. There was a picture.

Glossy, bright colors. A fox set upon by a group of sight hounds and torn to pieces. A gnawing anxiety growing within him as he turned the page to a picture of the hacked-off vulpine head, the tail, the paws. Kept by the hunting party as trophies. He took no pleasure in these images; he has always known that his particular viciousness is not the viciousness of his father, who meets all things with a violent contempt so total there is almost no need for the cruelty that inevitably follows it.

In a book, Carlyle scoffs. God willing, you’ll see the real thing tonight.

At the edge of the woods Carlyle parks the Ford and gets out.

Come on, he says. He has already grabbed another rifle from the back. Two hounds leaping from the truck bed to trail behind him, their ears flattened in submission. Like Nick they were bred to serve.

Nick adjusts the rifle strap and follows his father through the woods. Carlyle muttering to himself as they walk. His voice too low to discern what he is saying though Nick knows exactly what he means. Forced to witness the unending catalogue of his own failures, formed imprecisely as he has been in the furnace of his father’s ambition.

The dogs yelp and cavort in the shadow of the trees. The dappled branches menacing overhead as Nick trails behind his father, whose face is partially shrouded in darkness. Most of his father’s dogs are pure-blood greyhounds that hunt by sight alone, but from one crossbred litter he had begotten some bloodhound mixture, a monstrous and beguiling lurcher with a broad black snout. The dogs have no names, instead they are many-named: Rover, Fido, Rex, whatever capricious mood has caught Carlyle in the moment of calling out to them. Now the lurcher takes the lead, face pressed to the dirt, intent on flushing out its prey.

A peculiar trembling fills the air. Nick feels almost outside of himself, like he is observing this scene from afar. Knowing his father’s true designs he disdains them; he prefers the slow agony of fishing to the garish violence of hunting with the dogs. Watching as they course down any number of animals, returning, always, with the smug satisfaction that befits them. If Carlyle could have had dogs for sons he would have been a happy man; but when has a Morrow man ever been happy? No thousand acres, no grand inheritance can ever be enough to postpone their destinies. Nick will die as bitter as he came into the world. He knows this just as well at thirteen as he will in thirty years.

Peering into the darkness of the forest where hardly anything can be seen except what is pierced by the moonlight Nick catches a glimpse of the fox. A pair of pointed ears in the distance. He looks down the sights of his rifle, straight at it. His finger hovering over the trigger.

That’s my boy, Carlyle says.

One of the dogs startles, takes off running in pursuit. The fox darts away, a red smear in the landscape. A loud shriek resounds through the trees, a haunting cry like the scream of a woman, distorted somehow, a melody in the wrong key. Vanishing into a thicket like it was never there. Two of the hounds stop dead in the clearing, unable to pursue their quarry any farther. They return with their heads hanging, dismay in their eyes.

Carlyle grabs Nick by the collar of his hunting jacket. You missed the shot, he says. It was clean.

I had it, Nick mumbles. One of the dogs—

Did I ask for your excuses?

Nick shakes his head. His father releases his grip. Leaving no more of a mark on him than he usually does.

Looked too small to be a dog-fox, Nick says, finally. Must be a female. Could be a den nearby.

Carlyle steps forward into the clearing. There the dogs have begun pacing in an anxious circle. The lurcher perks his head up and barks once, twice. Lifting his paw and sticking his tail straight out it points directly at a half-fallen tree, hollow, already covered in moss and rotting away.

Carlyle gestures for Nick to come closer. At the base of the tree is an opening into which the lurcher peers with slavering intent. He brushes away the cover of dried leaves and sees two fox pups slumbering within.

She’s only got two of em. Still young too, Carlyle says. They are bright orange-red and just about the size of Nick’s outstretched hand. No tod in sight—elsewhere, maybe, or already hunted down by the dogs in a delightful afternoon game.

Pick one up, Carlyle orders.

Nick hesitantly puts his hand out and picks one up by the scruff. It is practically helpless, making only a pitiful noise that falls just short of a shriek. Nothing like the piercing woman’s wail of its mother.

Go on then, Carlyle says, gesturing toward the dogs gathered round. The pup dangles in Nick’s hand. He is unable to move his body, unable to understand what his father desires of him.

After a few moments of standing in silence, Carlyle says, Give me that. Seizing the pup from Nick’s arms so violently that Nick is left with tufts of fur in his hands. Instead of throwing it to the dogs to be torn apart he takes it by the neck and wrings it with a sharp crack. The head sags, lifeless. Carlyle grabs it by the ears and pulls it off completely, detaching the head from the body in a grotesque motion. Ignoring the spray of blood that hits Nick in the face and arm he tosses both pieces to the dogs. They feed on what remains, without malice, knowing only the profane thrill of teeth against bone.

Nick peers inside the den. The last cub lies sleeping. With a trembling hand he picks it up and pulls it out from the hollow tree. The dogs are sent into a frenzy of eager barking—or perhaps he only imagines them barking in his nightmares, years later. He closes his eyes and throws the pup, still alive, into their midst. He cannot force himself to witness this wild omophagia, weeping uncontrollably as he does this, wiping his face, blood and fur crusting his hands.

Stop that, Carlyle says. Nick feels as though he is being harmed by an outside force, a physical injury piercing him though his father has not laid a hand on him. He doubles over, shuddering in pain, before finally the attack subsides and he straightens himself upright. His face swollen and tinged red.

Are you finished? Carlyle says.

I’m finished, Nick says.

They trudge back to the car in silence. Nick looking down at his feet, unable to meet his father’s gaze. Once they reach the Ford before he sullies his father’s car with his stained hands he wipes them hastily on his pants. He will have to wash them later, hunched over his sink reciting his pathetic jeremiads to no one in particular. The dirt smearing his hands, the stain that will never leave him. With the dogs and guns piled high in the truck bed they begin their languorous drive to Stag’s Crossing. A place to which Nick can only turn back, looking over his shoulder at a fragment of the past.

On the dirt road east of the house his father slows the Ford down slightly, looking through the passenger-side window at the sloped ditch, the stretch of meadow covered in bloomless vetch. In the distance is the shadow of Stag’s Crossing, the charnel house that looms. The last gasp of spring almost upon them. He watches his father unlock the car and pull the silver interior handle of the passenger-side door. The gust of wind that enters nearly throwing him from his seat. Two of the dogs have leapt from the truck bed and are now gamboling freely in the shallow ditch next to the dirt road.

You’ll walk the rest of the way, Carlyle says. He puts his hand on Nick’s shoulder and he is shoved violently forward, tumbling out of the car and onto the rocky soil. He lands on his shoulder and winces at the sharp crunch of pain. Lifting his head from where he has fallen he can see his father’s Ford rounding the corner just ahead. His father has never been one to look back. Carlyle Morrow has never turned back in his life, not toward his children nor toward the city of Sodom that might burn so brightly in the flat plains outside Omaha.

In twenty, thirty years his father will ask Nick to stop reliving the past, for Carlyle has no understanding of it, this childhood that could scourge and wound with violence. Nick’s face blooming with a fresh bruise as he crawls on his hands and knees in the grass. A few of the dogs crowding around him, licking at his face and hands with wild abandon.

Overhead the birds swarm in agony, screeching and muttering to themselves. If this is a warning Nick cannot interpret it. He thinks about the animals he has just killed, their sacrifices without meaning. The feeling he had of killing that his father had attempted to impart the pleasure of, only to fail miserably. The softness of the fur he had grasped, understanding why they would be skinned for their pelts and hung in his mother’s old closet with the rest of her furs.

Through the yellow grass he crawls. Unable to stand up until he can no longer hear the relentless hum of the engine, can no longer smell the exhaust in the cloying air. Finally at the edge of the road he gets to his feet and pulls his jacket tight around his shoulders. Beginning the long walk back to Stag’s Crossing. The ground beneath him still treacherous in places, slippery and choked with mud. Only a few wretched dogs to keep him company.

As he passes through the veil of branches that heralds his return from the world of beasts into proper civilization he sees himself at last, clearly, reflected in the dew on the leaves. Joshua’s unlikeness, the impending cataclysm of his house. In all manner of ways he is marked by death; he stinks of it; like the third brother that tore open his mother on the way out.

II. NOW

At forty-three Nick has emptied himself of all nostalgia. His childhood a strange illness from which he will never recover. Out of necessity he has learned to feign the appearance of an ordinary man with an ordinary boyhood. Always ready with an amusing anecdote, a bland characterization of his father as strict. He might even believe himself, forger and plagiarist that he is, that the strike of his father’s hand slapping his broad and shining face was not unlike love. Perhaps not quite the same but close enough—just as he is close enough to the man he would like to be. His coldness, his fits of depression only apparent in the bleakest of winters. The trees hemorrhaging their leaves as promptly as he discards the trappings of civilization. With a voracious and bestial appetite he has consumed all his lovers, publicly savaging his acquaintances with eloquent condescension. Turning upon them knife in hand. Blood of his father blood of his brother cascading through him ceaseless as summer rain.

He has long vowed to be unlike Carlyle—named by his mother after the patron saint of children and thieves. Yet as time passes inexorably he grows more and more into his father’s cruel likeness seen through a cracked windowpane. None of the same handsomeness that afflicts his brother. His eyes have grayed and his hair has darkened to a still-vibrant mahogany but the jagged lines on his cheekbones are entirely his father’s. Second son of a second son.

Still his mind is cutting as ever. Having applied his vicious and mangling intelligence to literary criticism he is unfailingly erudite. After two decades set loose upon the world he has learned to affect the banal hostility of an East Coast intellectual. Sawing off all trace of a Midwestern accent from his anodyne English he is exacting in his deception; he refuses the moniker of America’s heartland and jeers at any hint of the provincial. No sense about him that he could unload and clean a hunting rifle in the dark without shooting his finger off nor that he has hunted geese knee-deep in brackish water a shorthaired pointer crashing into the lake after him. No sense at all that he has known the thrill of an apex predator vanquishing all manner of animal before him. Greyhounds with no table manners bloodying the foyer of his grand house with gore.

That was the Nick of his childhood. Now he is a different man, an impostor. Were he to return to Nebraska he would be a stranger at Stag’s Crossing. Prodigal son returning. Would he kneel before his father’s magnificence and eat oats from his hand like a wayward steer? Would he see his brother in all his glory like a young Christ in the house of his father?

Unrecognized he would come as a guest in his own home. His brother would embrace him and all would be well in that place where time has no dominion and memory is a mere recursion of the past. Where the edges of Stag’s Crossing might have been the edges of the known world and its centerpiece a two-story magnificence built by hand. His father intended them to be born and die there, as with all princes and their castles.

If only Joshua had not done the unforgivable. Married an unacceptable woman from an unacceptable family. If only Carlyle had not chased him from the house like an uninvited guest. Crowing: How dare you. I can’t believe it. You brought that bitch into this house. Have her as your mistress, do what you want. It’s all the same to me. But your wife! Your wife!

Nick watched from his bedroom window. His father’s rage shaking the floorboards of the house. Waking the spring cardinals and setting the sparrows to flight. Joshua turned back to his car where his wife waited for him and Nick saw her—saw the curve of her neck and the delicate parting of her hair.

Joshua said, Emilia, we’re leaving.

Emilia! O Emilia! Dark and burnished with dread falls that name upon the ear! He must cast her from his mind or else he will die; he must disdain them both. Awakening each day with the absence of his brother curdling within him like the wheat that rots on the stalk. To survive is to flee from the errant ways of his heart which goes where it pleases. But he could never defy the man who terrifies him more than God.

Unlike God his father will die one day. He takes pleasure in this fact. He hates his father so much he could die from it; he is almost sick with it. Yet each Saturday at midnight exactly he picks up the phone to hear Carlyle’s lamentations; castigations; a litany of his excruciating failures as a son. Carlyle’s voice on the phone an aged and conciliatory baritone. He apologizes and then forgets he has apologized. Sometimes he calls Nick a liar, a fantasist. You’ve got a great imagination, he says. No wonder you grew up to be a writer. Made up all those things you say I did but didn’t. Never beat you with a belt but my pops used to do that. Taught me right from wrong.

Having vindicated himself thus he might rage endlessly against the tyranny of old age—the Jews—the Viet Cong. The miasma of his hatred like a fog that obscures both vision and language.

Remember them? Slit-eyed, yellow as ochre.

Dad, Nick says. He is lying in bed with the receiver pressed against his ear. In an hour he might sleep or else he will lie awake all night thinking of Stag’s Crossing. His childhood bedroom. The smell of oak, pine, fresh loam. Crawling on his hands and knees from a roadside ditch, his coat spattered with blood. Out back with the dogs he would tumble, tangled between the long-reaching roots of a willow tree. Writhing in the arms of another boy, not so young now, never so young as they once were—

Remember how I once loved your brother just as much as I love you now.

I know, Dad.

Can you remember the last time you came back and visited your old man? Must’ve been years. Course I’ll be dead soon.

The last time he had visited his father, Carlyle had spent the entire visit complaining that Joshua never called. Nick felt it unwise to point out that being disowned tends to put a damper on family reunions and left after three awkward days.

You always say that.

My hip’s been giving me some trouble. I even fell last week almost went right down the stairs. Busted up the side real bad. Hurts to walk and get up sometimes so I went to the doctor and got a scan. It’s cancer.

You’re kidding.

No real treatment. Got a couple of months.

Nick says nothing in response to this. Debating whether or not he might half believe his father’s lunatic assertions. The constant proclamations of his impending death. Yet what Carlyle says seems true enough. In all his decades of brutality, Carlyle has never outright lied to him.

I want to die at home. If I get too sick promise you’ll put me down like a dog.

Come on.

Like a dog, Nick.

All right, he says. Turning the geometry of his infernal obsession over in his mind. His heart leaping with mad pleasure. He dares to think of the bastard wasting away, outlived at last. Perhaps his father will go the same way he came into the world; angry and angrier still. Or else it will be the thunderous passage of an era where men were once men and wielded their violence with an ancient and primeval ecstasy.

I’ve been thinking, Carlyle says. I’ve got no brothers or sisters back in South Carolina. They’re all long gone. Maybe I made a mistake with your brother. Family’s supposed to be the most important thing.

I don’t know what you mean, Nick says.

Call Joshua. Tell him he needs to come home. To bury me.

And his wife?

He can bring her too. After all these years, I forgot what I disliked so much about her. Maybe she was too arrogant for me.

It was not her arrogance that led him to drive the newly minted Emilia Morrow from the doorstep of Stag’s Crossing and they both know this. Nick lets it pass without comment. Slit-eyed, yellow as ochre. Carlyle has always feared an outsider at Stag’s Crossing since the death of his wife, whom he never mentions though his neurosis has been irrevocably altered by her painful absence. When the doctor from out of town said there was nothing to be done for her or the baby Carlyle would never again admit strangers into the house; he would stand in the doorway with a shotgun in hand the moment even the milkman opened the gate. Seeing in every newcomer the face of an intruder, an invader that must be repelled.

With the years Carlyle’s intimations have grown darker and more foreboding—in every blighted crop, every patchwork sale of unused land, he sees long-delayed retribution. His punishment for cutting down half of the woods to make a home for himself and his two disappointing sons. How many birds and rabbits and little foxes did he cut down likewise so that his children might have a future on those thousand acres of land. Now after all this he must accept Emilia Morrow at the doorstep of his home, this woman who portends ruin, who in another era more amenable to men like Carlyle they might have burned for sorcery. So decisive was her entry into the family. Even more decisive was her removal of Joshua from the fold, an uncanny and otherworldly act of seduction. Carlyle’s dread and resignation over the course of these events, inevitable and enraging, clear to Nick even through the telephone.

I’ll let him know.

Good. Don’t come earlier than Sunday. Have to clean the house first.

Yes, Nick says. He already knows which suitcase he will use, which shirt and ties he will pack. All his life he has been waiting for this, the graceful denouement. Standing at his father’s deathbed. The faces of the bereaved at the funeral. The long and endless afterward.

He dares not think of Emilia. Having looked upon her face once before he knows to recall her is a venture that will bring only disquiet to his carefully hermetic disposition. In the right-hand drawer of his writing desk he has stored all the letters she has sent him over the years. She was a painter before she married Joshua, or so she says; she sends him drawings. Whatever she can fit in a standard envelope. Charcoal and pastel studies of animals. Multicolored birds, dogs, a fox chasing a hare. On occasion she sends him a painting in the Chinese style. The colors muted, the brushstrokes superb and delicate. So thinly laid onto the paper they seem almost to shift before his eyes. Once she sent him a portrait of a woman in an Oriental robe, ordinary like any other, except for the nine bristling tails that grew from her backside. The woman’s face obscured by her long hair, her visage unrecognizable. The painting filled him with such unease he put it face down at the bottom of the drawer and did not look at it again.

He tries now to conjure an image of his brother whom he has not seen in twenty years. Joshua must be as marvelous as he was in his youth. His beauty is not the kind that listens to age. A face so handsome it borders on obscenity.

With a vain quirk of his mouth he could be mistaken for another Narcissus; yet his recklessness and disobedience mark him as a rebellious child of God. Eschewing the Morrow fortune, the bloody masterwork of his father for what Joshua might have called love but surely must be closer to hypnotic possession. How else to explain it? As he once set fire to Nick’s books he has now set fire to his family. His desire akin to self-annihilation.

III. THEN

The killing of a fox is one thing. The killing of its children, another entirely. Such a crime, once committed, can never be undone. That night Nick climbs the spiral staircase to the second floor of the house and scrubs himself raw in the bathtub. The stain of it lingering. He hardly eats for three days. Remembering the silent huffing of the dogs, the cracking of the bones as they chewed. The bruise on his face as he rose from the ditch. The little foxes, so small in his hands.

After a late supper he readies himself for bed with the most perfunctory of gestures. Combing his hair as his mother had taught him, when he once sat beside her at her vanity. Looking at her, at her reflection in the large mirror as she carefully parted his hair and combed it out for him. His father in the background, fixing his tie: Now, now, don’t give that boy any ideas. Don’t want him growing up like a woman.

Lying awake in his small bed beneath the slanted ceiling he pushes the image of his mother from his mind; she is long dead though he still feels a part of her perhaps remains present in the house. It is not something his father or brother could ever perceive or understand. Her voice in the wind, the soft touch of her hand in his hand when he is drifting off to sleep. These apparitions are not meant for them, they are Nick’s inheritance alone, cursed forever to bear her memory within him. The penitence of a mourner.

One of the dogs slinks up the stairs, nudging open the door to his bedroom. Pressing its wet snout into his hands. Insistent on something, though what exactly it is, Nick cannot tell. With the window open he can hear a few of the hounds taking off into a run toward the back of the house, letting forth a furious storm of howling. Unusual, for Carlyle bred his dogs to be seen and not heard, much like children.

Downstairs he fetches his boots, his jacket, the hunting rifle. Leaving quickly through the back door. The gun loose in his hands as he walks through the tall grass past the stalks of alfalfa and the bowed willow toward the chicken coop. He and his brother hammered it together a few summers ago when his father said if they wanted to eat deviled eggs every Fourth of July like they had when their mother was still alive they could raise the chickens themselves. With the moon bright and guileless he can see a part of the chicken wire is torn at the bottom where some animal has pushed through. Blood staining the wire. He goes round the back of the coop and sees eggs scattered and crushed in the dirt. A hen lying grotesque and headless on the ground. He gets on his hands and knees to look for the other half of it but cannot find it, only dried blood and feathers. Whatever animal came down to feast has already thoroughly enjoyed its nighttime aperitif and left. The firmament bearing the deep gashes of its claw marks, its shameless violence.

He bends the chicken wire back in place. Later he will come back and glue it down more firmly. Maybe put up a little fence around the coop if he has time after school. Not enough flesh left on the chicken for the dogs so he kicks some dirt over the corpse until he can come back with a shovel in the morning. Already half an hour past midnight and the stars are still brilliant as ever. Joshua once taught him some of their names but none of them come to mind now.

He walks back with the rifle tucked under his arm. If he were not Carlyle Morrow’s youngest and most serious son he might resemble a carefree farm boy in some bucolic Winslow Homer painting though his father has always favored the charcoal work of Goya. In the doorway he takes off his muddy boots and hangs up his brother’s coat. Unloads the rifle and hangs it on the wall next to the coat by its leather strap. The screen door falls closed behind him and he makes sure to latch it.

Swiftly and violently as a gunshot a scream pierces the sloped fields lying open and fallow behind the house. Sounding like a woman being murdered in the way he has seen it on television where her agony is drawn out over several breathless and voyeuristic minutes until he changes the channel. Yet he knows it is not a woman but some unnamable beast of the forest come to bewitch and maim. A mother despondent, in all her devastated keening—the fox whose children now reside in the stomachs of the hounds at Stag’s Crossing has finally returned.

He hastily locks the inner door as well but even that does not quiet the unholy calling that pursues him past the foyer and deeper into the house. In the fox’s wailing he recognizes the lamentations of the bereaved; with its children dead, it is an expression of grief without end. He knows he will only be safe in his bedroom under his three blankets where he can sleep with the lights on like a child. Up the spiral balustrade that snakes to the top floor he sees his father turn on the light and emerge barefoot in his long maroon bathrobe. He is unshaven and his guttural baritone is hoarse from sleep.

God damn it, Nick, he says, what’d you chase up back there?

A fox, Nick says.

A sliver of light escapes from beneath Joshua’s doorway—he is awake now too. He sticks his head outside gazing down at his brother with an imperious frown. Young princeling, seventeen and anointed successor his thick blanket wrapped around him like a royal doublet. Even having just awoken unkempt he is preternaturally handsome. His hair the color of sand struck by lightning. In ten years he will be lithe as one of the dogs and burn with the delicious pleasure of his attraction.

Fox? Joshua says.

Eating the hens, Nick says.

There’s a boy out in Blair who’s real good at hunting foxes, Joshua says. Could call him up and ask him to come out sometime. Goes by the name of Will Skog.

You think I’d let some nobody from Blair come here and intrude on our land? Carlyle says. His hostility flaring like the roar of the fireplace, stoked to a fierce blaze.

I can do it, Nick says.

Already had it right in your sights and you let it go. It’ll come right back. Once a fox finds a fat henhouse it’ll never leave.

I said I can do it.

Then kill it, Carlyle says. Kill it and be done with it. And let me sleep.

Nick says nothing. Without the gun he has no power in this house. His father could strike him dead where he stands. In some sense he has already been struck down, made to heel like an unruly cur fed and disciplined by the same decisive hand. When his father retreats into the blackness of the master bedroom he walks up the narrow stairs and to the small child’s bedroom with the slanted roof at the end of the hallway. The hallowed and forbidden place he will return to so often in his dreams.

He fixes the mosquito screen against his window and crawls into bed not having changed into his pajamas. Marveling at the garden strangely silent and smelling of fresh grass. The verdant scent of wealth pervading the house and the land that surrounds it. Watered by the blood of their family this apocryphal lineage carved into the Morrow name and resonating like thunder through each successive generation. He is Southern moneyed, Midwestern moneyed. Seeping into the earth and making an abattoir of his childhood stained now and forever by his birthright.

He lies awake listening to the terrible groaning of the house. As though Stag’s Crossing itself might grieve alongside the wilderness that surrounds it, the bowed willow, the black soil that swallows the fox-bones, the last remnants of what he has done. Years from now, when he is man enough to stand taller than his father, the garden will not rise to bloom again; it will lie fallow and barren as their family tree. Their line destined to end here, with him.

That night he weeps to think of his brother whose handsomeness has now begun to approach the sublime. Weeps to think of him running through the fields blood on his knuckles blood spattering the rye. Behind him comes Nick with his hunting rifle. Behind him comes the vivid premonition that one day when they are old enough to be called grown men Nick will usurp his brother and in this unholy annexation he will rise again as someone strange and new.

His regicide is imminent; ambition grows within him like a strangling vine. Second son, second born: Jacob above Esau, Isaac above Ishmael. Pretender to the throne.

IV. NOW

At his desk he ruminates without mercy. Scratching anxious lines into his face with slim fingers he is seized by a familiar and seductive neurosis. Like Daniel interpreting the will of God at Belshazzar’s table he must decipher his father’s edict. Summon Joshua back to Stag’s Crossing. Bury his father and with him the rage that has tormented Nick for decades. A rage that has disfigured him in body and mind. Has set him apart from others who in their anodyne lives cannot understand how deep and tumultuous this anger runs. Splintering him open like a fault line. When a man standing naked in his bathroom shaving says, Well, I’ve got a father hang-up too, Nick nods and says nothing. Steam from the shower shrouding his face, his expression of frank disgust.

Only his brother could understand these things: Carlyle and his whims, his insults, his strange genius. They are both forever unable to escape that place wherein lies the terrible essence of their childhood. Disgraced by their history that marks them indelibly as Carlyle’s sons. Returning to their father once more. He who has forgiven the transgression of Joshua’s youth in his magnanimous old age.

Nick, you know I’m a man of mercy, he says. A man of God.

He whose hands have beaten and baptized. He who has reckoned with idolaters and struck them down with his divine and inexorable will.

Have I ever wronged you? he asks.

No, Nick says. You haven’t.

What will Nick say to his brother, his brother’s wife? He has not seen them for twenty years. Each time they move—Minneapolis, Boston, Seattle, San Francisco—Emilia writes him an elegant letter enclosing their new address and phone number. Her lovely regards.

Joshua, of course, does not write.

He takes out the latest envelope dated September 1994 from the right-hand drawer of his writing desk. The letter and its envelope a delicate eggshell-and-cream color. Copies down the phone number inside with a madman’s scrawl onto a pad of paper and then rips the envelope in two and rips the letter in two as well. He cannot bear to read more than a sentence of Dear Nick, I hope this reaches you well—as though each word foretells some imminent disaster. His days of prophecy are over; he can no longer see what was, what is, what will be. What calls him back to Stag’s Crossing is not the providence of priests but something much more heretical. The exquisite euphoria of his envy and rage.