Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

How to Sell a Haunted House meets High Fidelity in this music store set horror about an A&R man who inherits a set of cursed records from his late father. Perfect for fans of Grady Hendrix and Paul Tremblay. After his estranged father's mysterious death, Charlie Remick returns to Seattle to help with the funeral. There, he discovers his father left him two parting gifts: the keys to the family record store and a strange black case containing four ancient records that, according to legend, can open a gate to the land of the dead. When Charlie, his sister, and their two friends play the records, they unwittingly open a floodgate of unspeakable horror. As the darkness descends, they are stalked by a relentless, malevolent force and see the dead everywhere they turn. With time running out, the only person who can help them is Charlie's resurrected father, who knows firsthand the awesome power the records have unleashed. But can they close the gate and silence Schrader's Chord before it's too late?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 611

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part I

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Part II

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Part III

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Part IV

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three

Fifty-Four

Fifty-Five

Fifty-Six

Fifty-Seven

Fifty-Eight

Fifty-Nine

Sixty

Sixty-One

Sixty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Scott Leeds truly has an ear for fear. Any reader who cracks this cursed book open is doomed to devour it in one sitting. Now I hear ghosts wherever I go.”

Clay McLeod Chapman, author of Ghost Eaters

“Schrader’s Chord builds with more twists and turns than your favorite prog rock epic, before reaching a phantasmagoric, surprisingly heart-tugging climax. But perhaps what’s most remarkable about Leeds’ debut is, for all its ghosts and corpses, how thoroughly it thrums with life.”

Nat Cassidy, author of Mary: An Awakening of Terror and Nestlings

“Scott Leeds knows music. He writes it true, and he writes it with grit. Then he somehow mixes all that knowledge and passion with a riveting, scary story and makes it sing. Schrader’s Chord isn’t just a compulsive read: it’s horror rock’n’roll.”

Wendy N. Wagner, author of The Deer Kings and The Secret Skin

“You’ll be looking over your shoulder as the pages fly in this hauntingly riveting debut. With gorgeous prose and chilling twists, the terrifying but heartfelt core of this family-centered ghost story seals Leeds as a powerful new voice in horror. Don’t miss it.”

E.G. Scott, internationally bestselling author of The Woman Inside

“Schrader’s Chord delights in the ghoulish and the bizarre. A dark and demonic debut.”

Leopoldo Gout, author of Piñata

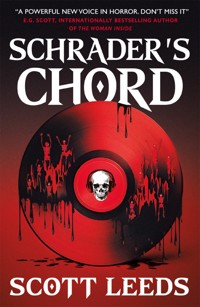

SCHRADER’S

CHORD

SCOTT LEEDS

TITANBOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Schrader’s Chord

Print edition ISBN: 9781803366821

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803366838

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Scott Leeds 2023.

Scott Leeds asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Mom and Dad

Jim opened the door wider and stood in the music, as one stands in the rain.

—Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes

The American businessman’s eyes glowed brightly in the fading sunlight as he watched the shopkeeper pull the object from the shelf. It seemed indefensible to him that an item of such value should be gathering dust in such a place . . . lost amid a sea of worthless flotsam and cheesy tourist souvenirs.

Even with the shop windows open, the heat was thick. The stale air sat bitterly on the man’s tongue, poisoned with decades of sweat and dust. Somewhere, buried in the mess of trinkets and baubles, a radio was on. Through its crackling speakers came the unmistakable sound of a baseball game, broadcast in broken English.

The shopkeeper grunted as he placed the object on the table, not because it was heavy, but because it wasn’t. He smiled a false smile, one that was well rehearsed, and looked up at his customer, his brow slick with sweat.

“Tall tales, Mr. Remick. I believe this is what you called them, yes?”

The businessman nodded.

The shopkeeper traced the object lightly with his finger. “Stories that grow with the light of time?”

“I suppose so, yes.”

“And what is it that grows in the light, yet disappears in the dark, Mr. Remick?”

The businessman was in no mood for riddles. The heat was unbearable, fraying his last nerve, and after all he’d been through—after the thousands of miles he’d put behind him over the past four months—his search was nearly at an end. All that remained was this transaction.

Thankfully, the riddle was easy enough to solve.

“A shadow.”

The shopkeeper smiled, showing his teeth this time. They were small, packed tightly into large gums, and stained yellow. “Yes! A shadow. That is correct.” His smile faded as he stared again at the object. “But the taller the tale, the longer the shadow, Mr. Remick, and this tale casts a shadow so long and so black, it will swallow all of life . . . until there is only death.”

The businessman pulled out his wallet.

“How much?”

PROLOGUE

Louis Goodwin sat in his car and waited for the sun to go down. Not that he needed to. The weather app on his phone told him that sunset was scheduled for 5:46 P.M., but here it was, only a few minutes past five, and it was already as dark as midnight. Through his windshield, he saw black clouds.

Black enough to blind a star, he thought, convinced he’d heard that line somewhere before. When he couldn’t place it, he flipped on his wipers. It had stopped raining nearly twenty minutes ago, but there were still a few scattered patches of moisture on his windshield. He watched his wipers stutter embarrassingly across the window, all but missing the resilient raindrops.

That’s what I get for buying the cheapies and installing them myself, he thought, staring balefully at the quiet street in front of him. Last spring, on a spur-of-the-moment drive up to British Columbia, Louis had stopped at a 7-Eleven in Bellingham to stock up on Corn Nuts and Diet Coke (his favorite travel combo) and had decided that he’d better switch out his tattered old wiper blades with some fresh ones. The Pacific Northwest was, after all, famously rainy, and it was one thing to putter around Seattle in his battered old Camry, but it was another thing entirely to putter around Vancouver (a city he barely knew) with a rain-sopped windshield and impaired vision. So, with the help of a YouTube tutorial on his phone, Louis stood in the parking lot of the 7-Eleven and switched out his old wiper blades with the new ones.

And they worked for a while. And then they didn’t.

And he hadn’t switched them out since. Why should he bother? They were the least of his worries.

The road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but Louis Goodwin’s intentions (which, as far as he was concerned, were as honorable as intentions got) would never lead him to a place as interesting as hell. If anything, his good intentions would most likely land him in hell’s waiting room.

He pictured spending eternity in a drab, windowless room with brown shag carpet, lifeless floral wallpaper, and corduroy couches with plastic covering.

And maybe that was what he deserved.

Louis had once overheard a colleague describe him over the phone. It had been a rare, after-hours occasion at work and his then officemate, Arlene Thompson, was making the obligatory call home to her husband. “At least I won’t have to go through it alone,” she had said wearily. “Louis is here.” After a brief pause, Arlene cast a quick glance at Louis, then turned away. “You remember Louis,” she said, then dropped her voice to a whisper, “he’s the one you called beige.”

Louis remembered feeling hurt by that, but as he sat in his car and gazed out into the shadows, he wasn’t really sure that beige could be considered an insult. If anything, it was an accurate (and economical) description. It was not only the color of his car, his suits, and his hair (or what little hair was left), but also his personality.

Louis Goodwin was beige, inside and out. He had passed through life quietly, rarely left a lasting impression on anybody, and was—for lack of a better word—boring.

Until now, that is.

A bead of sweat crawled down Louis’s forehead. He pawed at the airflow knob on his console and turned down the heat. There were no streetlights at this end of Wabash Street, and the house, which he’d been casing for nearly an hour, was as dark as the sky above.

Dark, and quiet, and waiting for him to make his move.

“I don’t know why you’re even bothering,” said a voice from the passenger seat. “Even if you don’t get caught, you’ll fail.”

Louis loosened his tie and gingerly rubbed his temples with his fingertips. A bolt of pain ping-ponged from one side of his head to the other. “I have to try.”

“And what if—and we’re talking a big if—you succeed? Then what?”

“I don’t know,” Louis replied, which was the truth. He chewed on his lower lip for a moment, then said, “I only know that if I sit here and do nothing, I’ll die.”

A snort came from the passenger seat. “I vote you do nothing, then.”

Louis wheeled around and stared into the cloudy, gray eyes of his dead wife. She sat straight-backed and prim in the passenger seat, dressed in the same shawl-collared cardigan she’d been wearing when she died. That was almost two years ago now.

“I don’t even know why you came, Deb.”

“Not come?” Deb said, delicately placing a palm on her chest. “And miss your debut as a master criminal? I wouldn’t dream of it.”

“Can you even dream?” Louis asked, eyeing her up and down as if he were a wary customer examining a beat-up sedan at a used car lot.

“Wouldn’t know,” she said flatly, then primped her hair in the side-view mirror. “Don’t need to sleep anymore.”

“You never slept much when you were alive,” Louis said, and thought about adding wickedness is a powerful battery, but thought better of it. When it came to the art of verbal fencing, Deb was maître, prévôt, and moniteur all wrapped up in one. Louis would only end up stabbing himself. “And anyway,” he continued, “I’m not even sure it’s technically a crime.”

“Breaking and entering isn’t a crime? Burglary isn’t a crime?”

“Raymond was my client,” Louis said firmly, then added, less firmly, “and my friend. He gave me the code to the garage door. Why would he do something like that if he didn’t—”

“He may have given you permission to enter his house, but I’m sure he wouldn’t like you taking what’s inside.”

“Whether or not he would like it doesn’t really matter anymore, does it? He’s dead.”

Deb crossed her arms. “And for most people, that wouldn’t be a problem, would it?”

Louis nodded soberly.

He didn’t know if he would ever get used to the idea of seeing dead people.

More often than not, he couldn’t tell who was dead and who was alive unless he was close enough to see their eyes. The eyes of the dead were vacant, emotionless, and oddly stormy, like little cups of black coffee dolloped with heavy cream. An unsettling image, to be sure, but not necessarily frightening. It was the violent or blood-soaked deaths that really frightened him. To see a man standing on a street corner with a shattered jaw, his teeth hanging by floss-thin tendrils of shredded muscle and gum tissue, waiting idly to cross the street as if his face hadn’t been caved in, froze the very marrow in his bones.

“If Raymond is still in there,” Louis said, nodding toward the house, “I’ll just explain everything. If anybody would understand, he would.”

“And what if he doesn’t let you take it?”

“Then the original plan stands. I take it anyway.”

Deb barked a laugh. “I don’t know where you’ve found this sudden surge of confidence, but I’m not buying it for a second.” She tilted the sun visor down and checked her smile in the mirror, giving the space between her front teeth a probing lick of her tongue. “You’ll shit the bed—like you always do—and slink out with your tail between your legs. And when that happens, I’ll have the delicious pleasure of saying I told you so.”

Louis fell silent as her words—cruel, but accurate—echoed through his mind. He wanted to tell her she was wrong this time, but since he had never found the courage to stand up to his wife when she was alive, it only made sense that he would find no such courage now that she was dead.

“Your ear is bleeding again.”

“I know that,” Louis replied, and pawed at the warm ooze running down his neck. He wiped the blood absentmindedly on his pants, leaving a fresh streak next to the older, darker, drier ones.

“That’s three times today. I’m guessing that’s not good.”

Louis frowned and opened the Camry’s door. “And circle gets the square.”

Outside, the air was crisp, appropriate for a December evening, and Louis watched his breath fog as he stepped gingerly onto the blacktop. Had there been a streetlight at this end of the block, he supposed he would have seen a curtain of fine mist descending beneath the glare of the lamp, but it was too dark for that. He could barely see his own shoes.

He closed the Camry’s door gingerly, turned back toward the house, and nearly yelped when he turned around and saw his wife’s face.

“Ready when you are,” she said, wiping the wrinkles from her cardigan.

Louis studied her warily. It was still a mystery to him how the dead moved. He couldn’t remember hearing Deb open the passenger door. Did she teleport onto the street? Did she just step out through the car? If so, that would mean she wasn’t solid, which brought into question her ability to sit in the passenger seat in the first place. Wouldn’t she just fall through it?

“I really wish you’d stay here,” Louis said, heart thumping. “I’ll be faster if I’m alone.”

“Not on your life, Winky,” she said, then strode confidently across the street toward the dark house, heels clicking loudly along the wet pavement.

Louis followed her up the long stretch of damp lawn. After looking both ways to ensure the coast was clear, he hopped over a row of hedges and collapsed into a clumsy somersault. He shot to his feet, knees stained by the dewy grass, then spun into the shadows next to the garage door.

If Deb’s eyes still had pupils, she would have made a show of rolling them. “Hope you remembered the code, Mr. Bond.”

Louis shimmied over to a white keypad that had been installed on a brick column next to the garage door. He flipped up the cover to reveal a set of glowing green keys. With a shaky finger, he punched in the four-digit code as the dull-as-dry-crackers theme from M*A*S*H played in his head.

“Four . . . zero . . . seven . . . seven . . .”

The door growled to life and Louis ducked into the garage. He weaved his way quickly through darkness, hissing as he caught his hip on the edge of a table saw, then skittered over to the door.

Deb, on the other hand, took her time. She sauntered slowly through the shadows, pausing here and there as she inspected the contents of the space. “Hell of a car this guy had,” she said, tracing the body of a 1953 Buick Skylark with her finger. The chrome arch that ran along its side glowed blue in the moonlight. “Takes some real heft between a man’s legs to handle a car like this.” She gazed up at Louis and grinned. “Not that you would know.”

A bitter tang climbed up Louis’s throat as he pushed her insult out of his mind. “No mistakes,” he said quietly to himself, pulling a pair of blue nitrile gloves tightly over his fingers, “no fingerprints.” He pressed a nearby button and watched the garage door rattle back down to the ground.

Deb smirked. “No fingerprints except for the ones you left on the keypad outside, you mean.”

Realizing she was right, Louis swore loudly, which, for him, meant a deep-throated “Oh heck.”

Deb snickered. “I love when you speak Minnesota. It gets me so hot.”

Ignoring her, he opened the door to the house and switched on his phone light. Inside, snow boots, sandals, tennis shoes, and a weathered pair of Crocs lined the wall of a narrow hallway.

“What are we looking for again?” Deb asked, glowering at the dirt-caked Crocs.

“A black case,” Louis said, and headed into the next room. “About the size of a microwave. It’s a bit beaten up, with two latch locks on it.”

They passed into what appeared to be Raymond’s office. Dozens of boxes lined the floor—some stacked as high as three or four—and formed a sort of maze. Louis moved his phone in an erratic zigzag pattern and watched as the thick beam of light climbed over the boxes, dove into the shadows, then resurfaced on a far wall.

“I don’t see it.”

He was disappointed, but not surprised. Finding it in the first room they’d entered would have been a lucky break, and Louis Goodwin had never been a lucky man.

And anyway, the treasure was never in the first room. As a boy, he’d read enough Doc Savage stories to know that much. X rarely ever marked the spot for Doc, and even if it did, it was never at the entrance of the catacombs. Doc had to hack his way through a cavalcade of gruesome creatures, deadly booby traps, and menacing henchmen to find the treasure.

Louis only hoped his quest would prove to be more uneventful.

He stepped softly into the hallway beyond, careful to keep the beam of his phone light low, especially around the windows. Deb followed him, heels clicking loudly. She made a point of commenting on anything that wasn’t to her taste, which, as it turned out, was everything.

Over the next ten minutes, Louis searched the living room, the kitchen, the ground-floor bathroom, the laundry room, and the pantry. He left no cabinet door unopened; no closet unexcavated. He even checked Raymond’s office a second time, just to be thorough.

The black case was nowhere to be found.

“Heck!” he said again, more forcefully this time.

“Came up short, huh?” Deb said as she watched Louis check the kitchen for the second time. “Why am I not surprised?”

“If it’s not in the house there’s only one other place it could be.” He took a chance and opened the oven door. Nothing. “And it’ll be a lot harder to break in there than it was to break in here.”

Deb, who had been somewhat amused by this boondoggle at first, had clearly grown bored. Had she still been alive, she would have yawned for effect, but since her brain no longer required oxygen, she chose instead to make her way back to the living room and take the ugly davenport near the front windows for a test drive. “You keep looking, Mugsy. I’ll send up a signal if I see the fuzz.”

Louis waved her off with an impatient hand and went back to the main hallway, cautious with his footing. The house was old and the floorboards were talkative, and even though they were alone and Raymond was dead, Louis had no desire to alert him of his presence.

Because Raymond was here somewhere. He had to be.

Over the last five days, Louis had encountered a number of things he had been unable to explain, but one thing that he had ascertained, with his wife’s help, was that the dead seem to reappear at the location of their death. Like Raymond, Deb had died at home, but unlike Raymond, she had been taken by a heart attack while sleeping peacefully in bed.

Raymond did not die peacefully in his bed, and Louis had no desire to be reunited with his client if the reports of his death were even half true.

He reached the end of the hallway and came face-to-face with a large staircase. From his tiptoes, he could see the first few feet of the second-floor hallway. Two doors faced each other on either side.

And behind those doors . . .

He pictured Raymond—God knew what his death had done to his face—sitting in a chair, bathed in shadow, waiting for him.

It was a nightmare of a thought, but Raymond or no Raymond, Louis knew he couldn’t leave until he’d checked every room. So, with an audible gulp, he placed his foot on the first step.

“Louis!”

He spun around with such force, his heel slipped off the edge of the bottom step. He grasped for the railing, but it was too late. Swiping at air, he landed with a thud on his backside and clapped a hand over his mouth to mask a shriek. He bent forward, reducing the pressure on the part of his undercarriage that had landed on his keys, then pulled himself up on his feet.

Deb came running through the foyer, cloudy eyes open wide, whisper-shouting something Louis couldn’t understand. But Louis didn’t need to understand. He already heard the noise.

It was the garage door.

“Somebody’s home!” Deb said, giggling like a schoolgirl who’d been caught smoking in the bathroom. Her hair bounced with every syllable, and even though she was dead, Louis could have sworn he’d seen her cheeks flush.

Of course she’s loving this, he thought resentfully.

“Come on!” Deb cried, and disappeared back into the foyer, almost skipping as she went. “If they see you, they’ll call the cops!”

An image of spinning red and blue lights, barking dogs, and handcuffs flashed through Louis’s mind. If he were to be arrested, his chance of finding the black case before it was too late would almost certainly vanish. And so, heart hammering, Louis bounded into the foyer after his wife.

They skidded into the living room and collided with the davenport, which screeched along the floorboards. Louis peered through the windows and saw a bright pair of headlights staring back at him.

There was a car in the driveway.

Louis ducked into the shadows under the main staircase and began to hyperventilate.

I’m dead, he thought, gazing up at the railing, which rose gracefully into the shadows and disappeared into the darkness of the second floor. Despair rolled over him like a thick fog. This is where it ends.

Deb flicked him on the bruised part of his temple. “Come on, Winky! Our goose isn’t cooked yet!”

Louis clenched his teeth. The pain was almost unbearable, but it had done what his wife intended. It had provided enough of a distraction to quell his defeatist thoughts. He snapped back to reality, and gazed over at his wife.

“Through the backyard!” she cried, finger in the air like Custer. “We’re gonna make it!”

Louis nodded, pausing to take one more peek out the window, then followed her.

When he got to the kitchen, the back door was already open and Deb was gone.

So she can’t pass through doors, Louis thought, then slipped quietly onto the back steps. He crouched low and eased the door closed, hissing at the coldness of the brass knob. He tore the nitrile glove off his hand and checked his fingers for marks. He looked again at the knob, expecting to see thin vapors rising from the brass, as if it were made of dry ice.

Around front, one of the car’s doors slammed shut, and Louis shoved his still-burning hand into his pocket. He crept down the steps and into the backyard, wincing as a snap of frigid air pinched his face.

Standing near a brittle rosebush, about five feet from him, was Deb.

She stood with her back to him, stone-still in the hazy moonlight. All of her excitement, all of her teenager-like vigor, had evaporated, and if it hadn’t been for the light breeze that sent shallow ripples through her cardigan, Louis would have sworn she was a statue.

“Come on, Deb,” he whispered, tugging at her sleeve. “Let’s shake a leg.”

But she wouldn’t move.

Something in the yard had caught her attention.

“Deborah, please,” Louis moaned, “if we don’t leave now, we’ll be—”

And then Louis saw it.

Thirty feet away, across the frosty, barren stretch of dark grass, the lifeless, gray eyes of Louis’s deceased client bored into his own.

Raymond’s face, glowing white in the moonlight, seemed to float in midair. He stared down at Louis, his milky gaze both focused and not, as his bloated, purple lips curled into a knowing smile.

“Find what you were looking for, Louis?”

PART I

ONE

I’ve got bad news in my pocket, Charlie Remick thought.

He closed his eyes and steadied himself against the load-bearing beam next to the soundboard. When he opened them, the world had righted itself, or seemed to. It was hard to tell in the darkness.

Jimmy, the guy running the soundboard, must have noticed the sudden change in Charlie’s weather and leaned over to clap a friendly hand on his shoulder. He asked Charlie if he was all right. Shouted it, really. The crowds at Brooklyn Steel never got big enough to achieve a chest-rattling roar, but tonight they were in fine form, whooping and hollering and clapping and whistling enough to beat the band . . . so to speak. The band wasn’t onstage yet.

Charlie nodded at Jimmy, forced a lopsided smile, and said he was all right.

He gripped his phone through his pocket. It was still buzzing with incoming text messages. He ignored it—or tried to—and decided instead to applaud with the other concertgoers, but there was something other than the bad news that made him uneasy—something that crept up his arms and forced the hair on the back of his neck to attention.

Dread, Charlie figured.

Or maybe something more sinister.

He sensed it, only for a moment—the way someone will catch a whiff of an oncoming storm in the air on a cloudless day—and then it was gone. Something big had been set into motion and he had been dragged aboard, an unwitting passenger along for the ride. He only wished he knew where he was being taken.

His pocket buzzed again.

Onstage, the lights went up—a cool mixture of blue and green—and the crowd maxed out the dial. The band took the stage, smiling and waving sheepishly as the applause reached a fever pitch, and when Joey Banes—the rail-thin singer of the Mightier Ducks—grabbed the mic and said hello, he blushed openly as three hundred (and counting) smiling faces answered him.

Charlie stood in his little spot next to the soundboard, arms crossed coolly over his purple corduroy blazer, eyes trained on the stage, looking every bit like the A&R man he was. Seth Larson, the Ducks’ drummer, gave the wing nuts on his cymbal stands a cursory—and entirely unnecessary—tightening. Charlie saw this and sighed. The wing nuts were already tight. Seth knew that. They had been tight at sound check and they were tight now. The kid simply didn’t know what to do with himself while the other guys fished picks from their pockets and plugged in their guitars.

Soon Seth would learn what all drummers eventually learn: just sit there and do nothing until you’re ready to play. Fidgeting with your cymbal stand doesn’t make you look like a pro, it makes you look nervous. And Seth looked nervous. They all did.

Charlie wished he could smile. These were the moments he loved. But the bad news in his buzzing pocket wouldn’t let him. With a decisive whip of his wrist, he pulled out his phone and powered it down. He hoped doing so would ease the invisible vise around his chest, but just before the screen went black, his eyes caught the text message that started this whole nightmare and the grip around his lungs tightened even more.

The text message.

The bad news.

Hey guys. Dad passed away last night.

His heart skipped a beat, then after a brief lull in his chest, hammered heavily on the return swing. He shook his head, trying to clear the words from his mind, but they remained—floating aimlessly behind his eyes, the way the sun will burn a ring into your closed eyelids on a bright day.

Hey guys. Dad passed away last night.

A loud squelch from the house speakers forced the crowd to cover their ears, and Charlie shot Jimmy the sound guy an icy glare. Jimmy merely responded with a whaddya gonna do shrug and dipped one of the faders on the mixer. Onstage, Joey Banes was having trouble plugging his cable into the output jack of his Strat. His hands were shaking badly.

“Jesus Christ, Joey,” Charlie mumbled impatiently. “Act like you’ve been here before.”

Jimmy the sound guy shot him a quizzical look. “You sure you’re all right, man?”

Charlie didn’t respond. He was embarrassed that he’d been heard. Joey Banes was a good kid. Seth, too. They were all good kids. And this was a big night for them.

So give them a minute for chrissakes, Charlie told himself. You’re just stressed. Stressed and worried and feeling guilty because it’s been five years since—

A wave of supportive cheers erupted. Joey had finally managed to plug his guitar in. He blushed again, giving them a bashful wave, and Jimmy the sound guy pushed the fader back up.

Charlie relaxed, but only for a moment.

Because the words were still there . . .

Hey guys. Dad passed away last night.

. . . hiding in his pocket . . .

Hey guys. Dad passed away last night.

. . . and with each subsequent buzz of his phone, more words were coming.

Which of his sisters had written the initial text? he wondered. He’d forgotten to look. Was it Susan or Ellie? And what’s more—he felt a pinch of anger now—who broke that kind of news over a text message?

It could have been either of them, really. Susan had always been a bit robotic in the emotional department and would no doubt prefer to break such news impersonally. Eleanor, on the other hand, never would have been capable of relaying such terrible words out loud without breaking into incoherent sobs, so a text message would be the more sensible—and efficient—approach.

Where was Ellie now? he wondered. San Francisco? New Orleans? El Paso? Was she back home already?

Charlie had always gotten along with his older sister, Susan, but he and Ellie were thick as thieves, and had been since the day they were born eleven minutes apart. They not only looked alike and talked alike, they had nearly identical track records when it came to their dismal dating life. They had their fair share of differences, of course. Ellie was a nomad, having lived in ten different cities in the past seven years. Charlie had lived in only one, and hadn’t planned on a second. Ellie was also a crier, and Charlie wasn’t. He wasn’t emotionally blocked or out of touch with himself. He felt his feelings like everyone else. He just didn’t cry. In fact, he could only recall two moments in his life that had moved him to tears. The first occurred while watching The NeverEnding Story for the first time (the memory of Artax the horse sinking into the Swamps of Sadness still severely bummed him out), and the second occurred while his mother’s casket was being lowered into the ground.

Two perfectly good reasons to cry as far as he was concerned.

And now here he was, presented with yet another perfectly good reason, and he couldn’t manage a single tear.

In fact, he began to laugh.

He couldn’t help it. It was too perfect.

Raymond Remick had died and people around him were cheering.

The timing was too on-the-money to ignore. If Charlie hadn’t been certain that such a thing was impossible, he might have suspected that his father had planned the whole thing.

One last wink of the eye from the old man as he passed from this world into the next.

Up onstage, Joey turned to his buddies, shared a quick nod, and then kicked into their first song, a real scorcher called “Olivia Quinn.” Charlie’s eyes drifted to the banner hanging above the stage. Emblazoned upon the vinyl in neat type were the words SONY BMG WELCOMES THE MIGHTIER DUCKS.

Charlie sighed. They would need to change their name before the record came out. It was a conversation he’d repeatedly kicked down the road for the last few months (he didn’t like to ruffle feathers during the signing process, especially since he’d already lost too many would-be signees to Sub Pop and Hardly Art and 4AD—labels that offered less money but more credibility than his current employer).

If it was done tactfully, Charlie should have no trouble convincing the band that names like the Mightier Ducks never stood the test of time. They were meta and stupid and only funny the first time you encountered them (if they were ever really funny at all), to say nothing of the fact that Charlie was in no mood to spend the next two years sparring with the Walt Disney Company over parody law, only to suffer a public loss and have to change the name anyway.

None of that mattered now, of course. The name change was a problem for tomorrow.

Tonight, Charlie had his own problem to deal with.

He let his hand drift once more to his pocket. His phone had stopped buzzing.

That meant that Ellie and Susan had graduated from text messages to a phone call, and Charlie was now out of the loop.

And there was nothing worse than that.

He spun around and eyed the path to the bathroom, but knew there wouldn’t be enough privacy in there. Brooklyn Steel had a bad habit of employing a bathroom attendant, and Charlie had no desire to read the details of his father’s death while an aging hipster looked on, hoping to sell him a two-dollar pack of Juicy Fruit.

Instead, he made his way toward the stage. There would be plenty of privacy in the green room, and even if there wasn’t, he could always kick people out. He hated power moves like that, but such were the perks of the A&R man.

The crowd was dense, but Charlie had perfected the art of the weaving walk, and as he approached the side of the stage, he flashed the laminate around his neck. This was more of a courtesy than it was a necessity, as the security team at Brooklyn Steel all knew him well by this point. Antoine, a beefy Belgian whose pectoral muscles tested the tensile strength of his black SECURITY shirt, shot him a brief smile and let him pass.

Once through the gate, Charlie turned and peeked out over the stage.

The view never ceased to exhilarate him. It was one thing to watch a band from the darkness of the crowd, packed and sweating in a throng of bodies. It was something else entirely to watch the crowd from the stage. A sea of faces, bathed in light, gazed up at the Mightier Ducks as they plowed their way through their soon-to-be first single, and although none of them were looking directly at Charlie—not that they could see him back there anyway—he still felt the rush of their eyes on him. And it felt good.

He allowed himself a few more seconds to sponge up a bit of vicarious glory, noted that the high E string on Joey’s guitar was a little flat (nothing he could do about that now), then made his way through the VIP section, which was mostly populated by roadies and girlfriends at this point. The groupies wouldn’t start showing up in earnest until the record had been out for a few months. After exchanging a few brief handshakes with the Sony brass, Charlie made his way into the green room and shut the door behind him.

The space was empty, and he was grateful. That meant he wouldn’t have to kick anybody out.

Luke the Shithead loved kicking people out.

He probably kicked his own mother out of the delivery room ’cause she wasn’t wearing a laminate, Charlie thought darkly, then switched on his phone.

He had thirty-eight missed messages.

With a flick of his finger, he scrolled back to the beginning of the thread.

Once again, he was met with the cataclysmic text.

Hey guys. Dad passed away last night.

It had been Susan who sent it.

Her next message—which Charlie was now seeing for the first time—did little to soften the blow.

I’m sorry.

Ellie had responded immediately.

WHAT?! Oh mu god Susan what happened???

Normally Ellie would have corrected such a glaring typo, but she let Oh mu god slide. Understandable, given the circumstances.

I just talked to him yesterday! He said he had taken some time off but when I asked him if anything was wrong he said no he felt fine!!!

Susan, ever the empath, simply replied: Yeah.

At this point, Ellie must have tried to call Susan, because Susan’s next text message read:

Sorry, Ell, can’t talk now. I’m at Maisy’s play. It’s almost over.

To which Ellie responded: YOU TOLD US DURING YOUR DAUGHTER’S PLAY?!?!

SUSAN: I only just found out. I wanted you to hear it from me instead of someone else.

ELEANOR: And you thought telling us over TEXT was the way to go??

There it was, Charlie thought. Twin-thinking. Ellie was right. Breaking the news over text was bad form, and Susan should have known better.

A shriek of laughter bolted past the door.

Charlie jumped, said “Fuck,” then rushed over and flicked the lock. The band would be onstage for another forty-five minutes at least, but that wouldn’t stop one of the girlfriends from popping into the green room to pass the time. He put his ear against the door and listened as the laughter drifted away. When he was satisfied his privacy wouldn’t be interrupted any further, he returned to his phone.

ELEANOR: And you thought telling us over TEXT was the way to go??

SUSAN: It’s not like I had a lot of time to think about it, Ell. I made a gut decision.

ELEANOR: Who told YOU?

SUSAN: Some girl who works at Dad’s store. I can’t remember her name.

ELEANOR: Was it Ana?

SUSAN: Can’t remember.

ELEANOR: What about Dale?

SUSAN: It was Dale who found Dad, apparently.

ELEANOR: Dad died at the store??

SUSAN: No.

ELEANOR: Then where?

SUSAN: He was at home.

ELEANOR: What was it? Stroke?

Then . . .

ELEANOR: Heart attack?

Then . . .

ELEANOR: Susan what was it??

Charlie noted the time stamps on Ellie’s last two texts. The first had been sent at 9:03 P.M. (6:03 P.M., technically, since both his sisters lived on the West Coast) and the second had been sent at 9:05 P.M. Ellie had waited a full two minutes for Susan to respond before following up. When no response came, Ellie tried again.

ELEANOR: Susan how did Dad die?

SUSAN: I really can’t talk right now. The play’s almost over. I’ll call you when I’m out.

ELEANOR: Jesus Christ Susan how did Dad die??

SUSAN: I WILL CALL YOU IN A FEW MINUTES.

There was another two-minute break, and then . . .

ELEANOR: Jesus Christ Susan this is so fucked up.

Charlie gave his screen a frantic flick of his finger, desperate to know more, but Ellie’s text merely bounced back into place.

The conversation had ended.

Out of nowhere, Charlie started to cry.

He turned toward the mirror and watched himself do it, although he didn’t know why.

He traced his oval jawline, gazed vacantly at his messy crop of mahogany hair and his slim build that had been harder and harder to maintain now that he’d passed into his thirties, and watched—in a strange, voyeuristic fashion—the tears stream down his cheeks.

He reached for a loose roll of toilet paper near the mirror and dabbed at his eyes. It was dark enough backstage that no one should notice their puffiness.

When his face was suitably dry, he went for the door.

* * *

The next twenty minutes were a blur.

He half remembered saying “My dad is dead, I gotta go” to a small group of people backstage as he walked out, but who those people were (and why he chose to divulge that information in such a way) remained a mystery to him. He had a vague recollection of the cab ride home and the nausea he’d felt as the rain lashed violently against the windshield.

Thanksgiving had been three weeks ago and, even though the city streets had been decorated with the customary symbols of yuletide cheer, the temperature hadn’t yet dropped below forty degrees. It looked like it was going to be another wet, snowless Christmas in New York.

It was still raining heavily when his cab turned north on Madison Avenue from Twenty-Third Street and Charlie told the driver to pull over. He had no desire to walk the remaining eight blocks in such a downpour, but his head was spinning violently and he knew if he stayed in the car he risked painting the plexiglass safety shield with the contents of his stomach.

By the time he reached the northeast corner of Madison Square Park, he was soaked to the bone. It didn’t bother him. His stomach had settled a bit and the violent thrum of the rain against the sidewalk had done a good job of distracting him from his thoughts. So did the rest of his walk. So did the squeak of his shoes on the lobby floor of his building. So did the elevator ride up to the fourteenth floor.

Once he’d keyed his way into his apartment, however, he was met with oppressive silence, and his thoughts came thundering back into focus.

He flipped on a nearby lamp and made his way to the kitchen, caring nothing for the trail of watery footsteps he’d left in his wake, and upon opening the refrigerator was met with the choice between a six-pack of Pacifico or a single can of Schweppes ginger ale. He opted for the Schweppes. Ginger ale was supposed to calm the stomach, and while he was certain there was no actual ginger to be found in the soda, he knew he’d regret the Pacifico in the morning. In his experience, beer was a lonely beverage, not content to be consumed as a single bottle, and a full six-pack would get him into trouble.

He collapsed onto the couch and took two quick pulls of the Schweppes, allowing the fizz to make his eyes water. After a minute or so of slow breathing and steady sipping, he pulled himself back up to his feet and hobbled over to the corner of the living room where he’d dropped his jacket. He didn’t remember taking it off. He shuddered at the squish of his wet socks inside his shoes, and bent low to retrieve his phone from the pocket.

He’d missed a call from Ellie.

He held his phone gingerly, as if it were a bomb about to explode.

There were now two timelines in his life: the time before the phone call he was about to make, and the time after it.

What horrors would the post–phone call Charlie know that the present one didn’t?

His father was dead. That much he did know.

But there was something else. He read Ellie’s text message again.

Jesus Christ Susan how did Dad die??

Susan never responded to that.

Why? If Raymond had died of a heart attack or a stroke, Susan surely would have said as much, wouldn’t she? Heart attacks and strokes were awful ways to go, but they weren’t exactly taboo. They were the number one and two dad-killers, common as colds, and Raymond Remick had lived sloppily enough to be prone to either, or even both.

So why not explain what happened over text?

Because this wasn’t a heart attack or a stroke.

This was something darker, something too awful to type into a phone and make permanent, and as long as Charlie didn’t make the phone call, he wouldn’t have to know what that dark, awful thing was. He could stay in the gray space between before the calland after the call where it was safe. He could sit on his couch with squishy socks and sip from a cold can of Schweppes for all eternity, having no knowledge of the terrible thing he was seconds away from learning. The can of ginger ale wouldn’t last for eternity, of course, so eventually he would be forced to go for the beer. And that was okay. If he was going to stay in the safe gray space, he would need something to do, and he sure as hell wasn’t going to sit there and not drink something.

He settled into the couch, feeling good about his plan, when his phone rang.

It was Ellie.

So much for the safe gray space.

He answered on the first ring. She spoke first.

“Hey.” Her voice was thick. She’d been crying. Heavily.

“Hey,” Charlie said back.

“Dad’s dead.”

“I know.”

“So you did see the messages.” Charlie heard her wipe her nose. “Susan and I were wondering.”

“Yeah, I was at a gig. Sorry.”

“It’s okay. We figured as much.”

“Did you talk to Susan?”

“Yeah.”

Charlie knew his next question would be to ask what Susan said, but he wasn’t ready to hear it. Instead he asked, “Are you gonna head home soon?”

“Mm-hm.” Another wipe of the nose. “I’m actually staying with a friend in Bellingham right now, so I’m close.”

“Bellingham?” Charlie felt a sting of resentment. He’d spoken to Ellie two days ago and she never mentioned she was back in Washington.

“Yeah. I was couch-surfing for a while . . . spent a few months in Minneapolis, then Portland . . . but now I’m crashing at my friend Hugo’s house. He goes to Western.”

Charlie felt his protective brotherly instincts kick in and wanted to ask who the hell this Hugo guy was, but kept quiet. It would have been easy to blame Ellie’s poor track record with men on her bohemian lifestyle, but that had nothing to do with it. The same way his corporate lifestyle had nothing to do with the rogues’ gallery of women he’d been with. He and his sister were swill magnets. Plain and simple.

The last woman he’d dated, Stephanie, once kicked her colleague’s dog at the park just because the little guy tried to lick her ankle.

A pearl of his father’s floated into his head. Any person who hates dogs never laughs for the right reasons.

And in Stephanie’s case, his father had been right on the money. Ten months ago, when they were still dating, the two of them had been walking home from a matinee showing of To Kill a Mockingbird and saw a woman snag her shoe on the curb in Times Square. She hit the concrete so hard her lip was bleeding, and as Charlie (and several other pedestrians) rushed to her aid, Stephanie hung back as tears of laughter streamed from her eyes.

“What about you?”

“Hm?”

Ellie breathed a quiet laugh. Spaciness was one of their shared traits. “When are you heading home?”

“Not sure,” Charlie said, which was the truth. He knew he’d have to go home, of course. He just hadn’t gotten that far yet. “I’ll have to tie up a few loose ends at work tomorrow, but I’ll probably start looking at flights tonight.”

“Good. I don’t know if I could face this with just me and Susan in the house, especially considering—”

The line went quiet.

Charlie sat forward. “You still there?”

Ellie’s sniffles crackled through the speaker. She was crying again.

Here it comes, he thought, feeling his stomach lurch skyward. Here came the terrible thing that Susan wouldn’t explain over text. He took another swig of his ginger ale, drained the can, and set it on the floor.

“It’s okay, Ell.”

“No . . . it’s not . . .”

Her words came quietly between shallow breaths, and as Charlie waited for the hammer to fall, he felt a surge of nervous adrenaline. “Just tell me, Ell. Whatever it is, it can’t be worse than what I’m imagining.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure about that.”

“Just tell me.”

She paused, took a breath, then said in an almost eerie calm, “Dad hung himself from the Grim Tree.”

* * *

Charlie would only remember bits and pieces of the conversation that followed, but after he said goodbye and hung up the phone, he had no trouble remembering his trip back to the refrigerator.

He decided to have that beer.

And then, when that beer was finished, he decided to have five more.

TWO

Somewhere far away—farther than that, even—the Dixie Cups sang about their grandma and your grandma, sitting by the fire . . .

Ana Cortez opened her eyes. Pale light cut thin blades through her venetian blinds and spilled across her bedsheets in staggered lines. She yawned, her limbs quivering a little as she stretched, then pulled herself to her feet.

The Dixie Cups sang another line—this one being about a king all dressed in red—and Ana shuffled groggily into the living room of her two-bedroom Seattle apartment, searching for her phone. She passed by the window and stole a quick glance outside.

Gray and wet. Surprise, surprise.

She shivered. Her oversized Tears for Fears shirt and boxer shorts did little to protect her from the chill in the air, but she would see to the thermostat in a minute. She was on a quest, hunting the muffled sound of the Dixie Cups like a sleepy bloodhound.

All around the living room, stacks of records stood in uneven columns like wobbly Jenga towers ready to collapse at any moment. She staggered over to the couch, circumventing a stack of rare 45s that was one light breeze away from toppling, and plunged her hand between two cushions.

Her phone was wedged tightly, and as she pulled it free, she shuddered at the ringtone’s change in volume.

Jock-a-mo fee-no ai na-ney, her phone sang loudly, pounding away at her ears. Jock-a-mo fee na-ey.

She swiped right on the little green phone icon. “Iko Iko” disappeared and was replaced by the sound of her mother’s frantic voice.

“Ana? Are you there?”

“I’m here, Moochie.”

“I’ve been calling for hours! Where have you been?”

Ana glanced at her watch. Mickey Mouse’s hands told her it was just after 2 P.M. She swore loudly.

“Ana Cristina!”

“Sorry, Mama. I didn’t realize how late it was.”

“You only just woke up?”

“Uh-huh.” She suspected her mother would disapprove of this, but Gloria Cortez was the sort of woman who knew when to pick her battles, and today was not that day.

“I suppose you have a right to sleep late.”

Ana felt her shoulders relax. Her mother wasn’t as hard-nosed and unbending as she seemed, but she wasn’t a total pushover, either. After Ana’s father died in a car accident in ’92, circumstance had forced Gloria to be more like her own mother instead of the mother she’d planned on being. The sudden death proved to be an unpleasant echo for Gloria; a mirror image—although slightly distorted—of her own upbringing. An academic essayist turned political journalist, Gloria’s father had been among the first to publicly voice his criticism of Marcos Pérez Jiménez’s regime, and had spent the rest of his life in prison for doing so. And the rest of his life, it turned out, was a visible mark on the horizon. Six years into his sentence, he succumbed to a particularly violent bout of tuberculosis, and died on a Friday morning. Gloria still had the letter informing her and her mother of the news.

It seemed the women in her family were cursed. Cursed to lose their men.

Or perhaps it was the other way around. Maybe it was the men who bore the black mark.

Either way, Gloria feared for the poor soul Ana would eventually choose to love, whoever he might turn out to be.

The hardship of single parenthood had become something of a ghoulish tradition in their family, and had resulted in a no-nonsense, military-style approach to Gloria’s parenting. Ana often wondered if her mother would have been so strict if she’d remarried, but the prospect of a stepfather was, to her knowledge, never considered; Gloria had been, and was to this day, still hopelessly in love with her deceased husband.

She still spoke to him when she thought Ana wasn’t looking, and, for a lengthy period in the nineties, would watch Walter Mercado on TV next to an empty chair, arguing the validity of astrology as if he were sitting right next to her.

Ana might have only been six years old when her father died, but she had no trouble remembering the amused-slash-pained look on his face as her mother credited his everyday actions and decisions to a celestial crab.

In fact, when Ana considered all the evidence, it was a miracle she’d been born at all. As a young man, Diego Cortez had been a staunch pragmatist—a computer science and engineering professor at the University of Washington who had very little patience for anything that couldn’t be reduced to a series of ones and zeros.

When he met Gloria Salguero, a young Venezuelan exchange student, he thought he’d found a kindred spirit. She was taking advantage of a Microsoft-funded program that taught MS-DOS to Spanish-speaking academics in the hope they’d return to their country of origin and spread the Gospel of Gates. But, as it turned out, Gloria cared nothing for computers. In fact, to Diego’s horror, she believed computers would lead to the downfall of humanity, plunging Earth’s populace into a morally bankrupt feedback loop that would be broken only once technology was abolished and every last microchip reduced to dust.

But the program did come with an all-expenses-paid stay in the United States, so she figured what the hell. She would stay in Seattle and engage in a battle of wits with the handsome Cuban Computer Boy for a few months, then head back to Venezuela and find a suitable man with a healthy distrust of technology. All she had to do was make sure she didn’t fall in love. If she fell in love, she might never leave.

Nearly thirty years later, she still hadn’t left Seattle.

“I’m happy you finally took a day off,” she said to her daughter. “You work much too hard.”

“It wasn’t my decision to close the store. It was Dale’s.”

“That poor man . . . I can’t imagine what he must be going through.”

Ana bit her lip. “I’m going through something, too, Mama.”

“Oh, I know, sweetheart, I know,” her mother said quickly, sensing she’d just stepped in conversational horse shit. “I just can’t stop thinking about what he saw in that backyard. Raymond hanging there like a rag doll. It’s just . . .” She whispered a fragment of a prayer under her breath. “It’s just terrible.”

Ana’s eyes moved again to her window. The rain was falling more heavily now. “Yes, it is.”

“Why don’t you come home? Just for a few days. I’ll cook you whatever you want.”

“I need to be at my own place.”

“I don’t think you should be alone right now. I can help you.”

There was only one person that could truly help Ana, and Dale had just found him hanging from a tree in his backyard. “I’ll come visit for a bit after the funeral, Mama. We’re gonna open back up tomorrow and I’d rather stay on this side of town.”

“Is it wise to open again so soon?”

“Christmas is just around the corner. We can’t afford to shut the doors right now.”

This was both true and convenient. If Raymond had died in, say, October, Dale probably would have closed the store for a week or two, but Christmas accounted for nearly twenty-five percent of their yearly earnings and, tragedy or no, it would be silly to risk losing the store out of respect for its dead proprietor. Even Raymond would have agreed with that.

She bandied a bit more with her mother, assured her for a second (and third) time that she would rather stay on her side of town, then made up a lie about an incoming call and hung up. After another minute or so of staring out the window, Ana made her way to the kitchen and whipped up a quick breakfast composed of a cold Pop-Tart and a reheated cup of coffee.

Once she’d eaten, she reentered the living room, a little more awake and a lot more frustrated. She might have been reeling from the news of Raymond’s death, but sleeping past two in the afternoon wasn’t like her. She’d always been an early riser, ever since she’d gotten her first job at fifteen.

The job that set her on a path to the Cuckoo’s Nest and into the employ of Raymond Remick, and the pain she was now feeling.

After scouring the Northgate Mall and coming up short (Claire’s and Sam Goody and Orange Julius had been fully staffed-up for the summer), she secured a position as a ticket-taker at the Varsity Theater, a small two-screener near the University of Washington. Her manager, a crusty old stoner named Rod, had hired Ana on the spot. She was young, but she was eager, which was more than could be said of his other employees. On top of that, she seemed to know her stuff (Bergman good, Michael Bay bad) and, because she was so young, she was willing to work for cash under the table. Lastly—and most importantly—when Rod shook her hand, he caught the distinct smell of pot on her jacket.

Ana liked her job at the theater. Because of its proximity to the University of Washington, it was always busy, owing mostly to the steady flow of students who were itching to see their favorite classics represented on the big screen, and it opened later in the afternoon, which meant her school schedule was never an issue. She could smoke pot when she wanted (usually with Rod, who was comically unaccustomed to the stronger modern strains), and take breaks whenever she wanted, and although the job didn’t pay much, it paid enough to feed her one true obsession: music.

Having lived in the Fremont area of Seattle her entire life, Ana was no stranger to the Cuckoo’s Nest, a local record store that had become a go-to destination for music-obsessives all across the Pacific Northwest. She’d popped into the store a few times during her youth to pick up the odd CD (Soda Stereo’s Canción Animal and No Doubt’s Tragic Kingdom among them), but it wasn’t until the summer after her freshman year of high school that she became a regular staple among the store’s clientele. It was the summer she stepped into the store not as a casual music fan, but as an addict in need of a fix.

And it all started at the lake.