Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

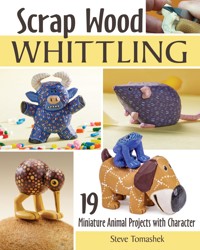

Scrap Wood Whittling is a must-have guide for any woodcarver looking to achieve something small, charming, and easy! Small wood carvings tend to intimidate, but author and master carver Steve Tomashek makes it approachable for anyone, even beginners. Opening with helpful insight on materials, tools, cuts, and safety, you'll then go on to complete 19 tiny animal carvings that slowly progress in difficulty. From a leaping pig and a penguin family to an aquarium and cat diorama, each project contains clear, step-by-step instructions, coordinating photography, full-size patterns, tips on technique, painting, display ideas, and more!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication

I’d like to dedicate this book to my farm family: my wife Randi, our daughter Winona, our son Wyatt in the stars, plus the countless critters who inhabit our land. I feel charmed to live among them, enjoying their warmth and strength.

Acknowledgements

I want to acknowledge my best friend, mentor, and all around cool guy, the late Glenn Gordon. His wit and wisdom are dearly missed. Glenn was a skilled woodworker, writer, and photographer. I worked with him photographing my carvings periodically over the course of almost ten years and enjoyed his friendship through biking and chats over coffee. His knowledge and vision helped me to see the forest through the trees.

I want to acknowledge my sister, Ann Johnston. Her support gave me the space to develop my skills as an artist when it was not clear that I could make it work. Without her help I couldn’t have survived as an artist and this book never would have been written.

I also would like to acknowledge the tool makers, Del Stubbs and Peter Lucas among them, for their craft and artistry in making the instruments we whittlers use.

© 2022 by Steve Tomashek and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

Scrap Wood Whittling is an original work, first published in 2022 by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc. The patterns contained herein are copyrighted by the author. Readers may make copies of these patterns for personal use. The patterns themselves, however, are not to be duplicated for resale or distribution under any circumstances. Any such copying is a violation of copyright law.

All step-by-step, getting started, and technique/tool photos by the author. All glamor photography by Mike Mihalo. The following images are credited to Shutterstock.com and their respective creators: p. 6 (ancient horse): Villy Yovcheva.

Print ISBN: 9781497101685eISBN: 9781607659266

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941284

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

For a printable PDF of the patterns used in this book, please contact Fox Chapel Publishing at [email protected], with 9781497101685 Scrap Wood Whittling in the subject line.

Introduction

The state of Minnesota, where I grew up and spent most of my adult life, is known for an abundance of soft, clear basswood and long, cold winters, which are excellent conditions for an aspiring woodcarver. A blizzard is the perfect time to stay inside, grab a chunk of wood, and whittle away the hours; such was my childhood. From my bedroom window I could see two giant basswood trees on the boulevard; the city erased them when they started to hollow, but they each could have fueled lifetimes of whittling. It may not have been destiny, but I was pointed toward carving and ran with it.

My niche has always been animal miniatures. I’ve chosen not to work at a consistent scale but rather to carve in sizes that relate to the human hand. I’ve created a menagerie, a collection of exotic animals. Some took ten minutes to make; some took ten hours. My miniature menagerie has thousands of carvings and hundreds of species representing years of exploring the animal world. I’ve studied and created animal art for over twenty years, and this book allows me to share some of that experience.

The object of this book is to set forth a collection of miniature animal projects that meet learners at all levels of experience and that require only a knife. Fundamentals and simple projects are explained in depth to start the beginner on the path to realize the fun and fulfillment of whittling. The novice can slowly gain confidence and skill as they learn to carve intricate details using illustrated step-by-step instructions. More experienced carvers will find value in the projects that focus on the major themes in my process and art form. Every learner will benefit from the multitude of tips, ideas, and plans as they explore this unique style of painted sculpture.

I organized this book by skill level; basic information and techniques are explained and illustrated in the first chapter, and then a group of simple step-by-step projects and plans are provided for the beginner. The next set of projects introduces increased complexity and detail work with a group of jumping animal figures. In the next set, each project examines a different theme while providing step-by-step instructions for whittling a diverse cast of miniature animals. The last set of projects includes dioramas that explore concepts like scale and space while thinking and creating inside a box. Interspersed throughout are tips and tricks gained through years of experience.

Please enjoy exploring this miniature world of animal wonder!

—Steve

Table of Contents

A Brief History of Carving

Getting Started

Wood

Tools

Sharpening and Tool Maintenance

Designing Your Project

Carving Techniques

Painting and Finishing

Projects

Easy Projects for the Beginner

Mouse

Penguin Family

Duck

Dinosaur

Intermediate Projects for the Apprentice

Leaping Pig

Leaping Goat

Leaping Leopard

Leaping Rabbit

Leaping Horse

Themed Workshops

Miniature: Frog

Design: Minotaur

Nature: Sea Turtle

Sculpture: Kiwi

Painting: Rooster

Caricature: Dog

Working inside a Box

Aquarium Anglerfish

Cat in a Window

African Safari

Moby Dick

Resources

About the Author

A Brief History of Carving

The current, standard definition of whittling is the art of using a knife to sculpt objects out of wood. It’s a form of woodcarving, but without chisels, gouges, mallets, chainsaws, or angle grinders. If woodcarving is poetry, whittling is haiku: the constraint of the form is also what makes it unique and elegant. It’s deceptively simple; knife meets wood. The beauty of a single tool means there’s just one tool to master. It’s a populist and portable art form: for the cost of a knife, wood, and a few accessories, you’re ready to take your workshop with you.

Humans have been carving for a baffling number of years. Before written language, before farming, even before dogs, we were whittlers. Some of the earliest miniature sculptures have been found in caves in Germany: miniature ivory animals, 30–50,000 years old. They mark the emergence of the completed human species, a craftsperson. Working ivory with stone tools was not a five-minute project; these figures signal the dedication of a community to the craft. Humans had been tool tinkerers for 2 million years already; wood of all dimensions would have been the primary material. The presence of these miniatures raises many unanswerable questions; but what we know for sure is that these humans had the luxury of sitting around whittling.

The horse was one of the first animals to be recorded sculpturally in the human record.

In the United States, whittling became popular after the Civil War with the growth of transient populations. It was a perfect pastime for the itinerant laborer, and many became anonymous masters of a repertoire of items that included wooden chains, ball-in-a-cage, animals, and religious figures. The advent of the Boy Scouts helped spur further interest, so much so that whittling was long considered the preserve of boys and old men. Nowadays, anyone can try their hand at the peace and peril of sculpting wood with a knife.

The thought of whittling may seem obsolete in an era running at the speed of the newest technology. The distraction our electronic gadgets provide us is intoxicating; the slow work of whittling is, for some, the antidote. The creative place we can inhabit while whittling is absorbing, meditative, and challenging. The end product is a tangible object, unlike the many ethereal tasks we perform via computer. We can hold our creation, the work of our hands; it connects us to the real world and reaffirms that we humans are forever artists and craftspeople.

This ancient ivory carving, discovered in the Vogelherd cave in Germany, dates back to at least 29000 BCE and is one of the earliest known carvings of a horse.

Getting Started

Wood

Of the 60,000 species of tree on our planet, a handful produce woods that are easy to carve. Wood is highly variable, even within the same species. Wood that is dry or “seasoned” will be harder to work than freshly cut or “green” wood, but green wood has a tendency to split if it’s not dried properly. Carving wood must be taken slowly: hands will get sore, knives will dull, and it can be a frustrating and dangerous first experience if the wood is not suitable. Common woods like maple, birch, walnut, and oak are not recommended for beginners. You may find good carving wood at hobby stores, lumber mills, or via mail order; knowledgeable tree trimming services and fellow woodworkers are also possible options.

Recommended

Basswood (Tilia americana), a hardwood, is the best wood for beginners and has been used for some of the most accomplished woodcarvings ever made. Trees of the genus Tilia, which includes basswood, linden, and lime, produce wood that is famous for its uniform texture, and it’s one of the lightest woods formed by deciduous trees. Usually free of knots or irregularities, it carves easily and holds detail well. The wood is plentiful and inexpensive. Whittling it requires little strength, and your knives should stay sharp a long time. Forest-grown basswood that has been air dried for at least 6–12 months will be softer than kiln-dried basswood. Wood harvested from near the Canadian border will work easier than wood from southern sources. It’s some of the best carving wood in the world.

Scots pine

Norway spruce

Basswood

Softwoods

Coniferous trees produce softwoods that are usually easy to whittle, but there are exceptions and caveats. Knots, resin, and splintering are the biggest problems with many softwoods. You must take extra care if you need to carve details. Trees grown in colder climates or at higher altitude will provide denser, more fine-grained wood due to a slower rate of growth.

Scots pine (Pinus sylvester) is widely cultivated for construction lumber, but as a result it’s wildly variable in quality. Look for pieces with no knots and a tight grain. While it’s easy to work, details will present a challenge and require extra caution. Wood should be seasoned for 6–12 months before using. High resin content may also interfere with finishes.

Norway spruce (Picea abies) is also used for construction, but it is perhaps best known as the common Christmas tree. Like pine, it should be seasoned for 6–12 months before using. It will be easy to whittle as long as there are no knots present, but take special care when working in small dimensions.

Yellow cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis) grows along the northwest coast of North America; quality wood outside this range may be expensive. It is easy to carve and has a fine, straight grain. It holds detail better than most softwoods due to its slow growing conditions. Yellow pine, white pine, and Douglas fir are also reported to carve similarly well if grown under the right conditions.

Yellow cedar

Hardwoods

If, like me, you have access to a fruit orchard, yearly pruning will provide a bounty of branches especially suitable for miniature projects. Fruit tree wood is generally rather hard and not recommended for the beginner, but the typically reddish brown colors take on beautiful natural finishes. Consider using the woods for simple projects like keychains or pedestals for your carvings.

Pear (Pyrus communis) wood has a very fine, straight, and uniform grain and a smooth and consistent texture. It is one of the finest hardwoods in Europe, but it is rare and expensive outside Europe. It’s an excellent whittling wood that holds detail well, but expect to sharpen your knife often and only remove small pieces of wood with each knife stroke.

Pear

Cherry (Prunus serotonin) wood is popular and expensive due to its attractive color and gentle figure. That figure can also make it more difficult to whittle than its hardness would predict.

Cherry

Apple (Malus domestica) wood is remarkably similar to cherry, though not as popular. Due to its hardness, it is a difficult wood for a beginner. The grain is very fine and uniform with alternating streaks of color.

Apple

Plum (Prunus domestica) wood is often knotty and irregular but has a fine, tight grain. It’s easier to work than most fruit woods, and it can usually be found in just small amounts. It’s the most colorful of the woods listed here, often containing streaks of red, pink, and purple.

Plum

Of the harder woods, I use boxwood Yellow cedar (Buxus sempervirens) for its ability to hold detail. The grain is fine, straight, and uniform, and the wood is hard and strong. This wood is often used for netsuke miniatures, a Japanese form of ornamental figure carving. When I’ve used it, I employ files for details and saws or a Dremel to rough out the figure.

Boxwood

Tools

To carve the projects in this book, you’ll need to assemble a small collection of tools. You’ll need at least one whittling knife with blade protection, sharpening tools, safety equipment, a first aid kit, a miniature pin vise and drill bits, a saw, a set of acrylic paints and brushes, a pencil, a pen, a drawing book, and sandpaper. When I travel with my mobile workshop, I pack these items in a cigar box (sans saw) and with a little pile of scrap wood. I hit the beach or find a stump in the woods to sit on and let the chips fall where they may.

Knife: The most important tool in the whittler’s toolbox is the knife. It must have a carbon steel blade that is hard enough to hold an edge but not too brittle. The shape and size of the handle and blade are personal preferences. I prefer having one large-bladed knife and one smaller detail knife. The knives I used for this book are the 2" (5cm) Harley knife made by Pinewood Forge and a few detail knives from OCC Tools, David Lyon, and Peter Lucas. For an inexpensive all-purpose alternative, I recommend the Kirschen 3358 carving knife with a Murphy style blade. When it's not in use, keep your knife sheathed for your own safety and for preservation of the cutting edge. If your knife did not come with protection, build your own blade sheath from leather, cork, or rubber tubing.

Sharpening tools: To keep your knife razor-sharp, you’ll need a strop and stropping compound; to repair a damaged blade, you’ll need sharpening stones. Strops are pieces of either smooth or suede leather; sometimes one or both versions are fixed to opposite sides of a piece of wood. Stropping compound is an abrasive powder or paste; examples include green chromium oxide and white or gray aluminum oxide. Sharpening stones come in sets of varying coarseness: Arkansas, ceramic, diamond, and India stones are all adequate. At a minimum, you’ll need one coarse and one fine stone—for example, a 600-grit and a 1200-grit.

From left to right: pencil, pen, drawing book, micro drill bit set, coping saw, miniature pin vise, sharpening stone, carving knife (Pinewood Forge), detail carving knife (Peter Lucas), sandpaper, leather strop, aluminum oxide stropping compound, paintbrushes, acrylic paints, rubber finger protector

Safety equipment: I recommend that beginners start with a safety glove to use on the hand holding the piece of wood; the gloves resist slicing cuts, but not stabs. Some whittlers, including myself, use leather, rubber, or taped fingers that function like an extra layer of skin. Though they will not stop forceful cuts, they will absorb low-intensity cuts. I wear a rubber finger to keep the knife off my carving hand thumb. If you’re sanding wood, wear a mask to keep harmful dust out of your lungs. Keep bandages handy; while it takes some effort to pass a knife through wood, skin offers little resistance. A poke with a knife will ache, but a long slicing cut will require stitches or worse, so be safe.

Miniature pin vise: A pin vise is a miniature drill clamp attached to a handle that you turn by hand. You use it to drill small, precise holes. This allows you to control the depth, location, and direction of a hole to a high degree of accuracy. These can be purchased together with a set of drill bits that fit the chuck of the tool. In this book, you will use the pin vise to drill mounting holes in your carvings so that you can insert a toothpick to hold the carvings while you paint them.

Saws: You’ll need to cut wood to the right dimensions at the start of each project. Multiple types of saws come in handy to cut up lumber and rough out pieces of all different dimensions. Handsaws like a coping saw should be used on wood that is secured by a clamp. A scroll saw will work if the wood you’ve got is already cut into small pieces. A bandsaw is the best all-around tool for cutting and roughing out. I also use a miniature table saw to make the small boxes in the last set of projects.

Paint and brushes: Use a quality set of acrylic paints to color your projects. You’ll need at minimum five colors of paint: blue, yellow, red, black, and white. For brushes, a couple of #1 and larger round brushes of moderate quality and a high-quality liner detail brush will do the trick. The detail brushes used in salons to paint fingernails work well.

Other tools: Round out your toolbox with a pencil for drawing on wood, a pad of paper and pen to record your ideas, and sandpaper (150-, 300-, and 600-grit) for smoothing surfaces, if desired.

Sharpening and Tool Maintenance

Keeping your knife razor sharp is an important skill to learn, as it not only makes whittling easier and more enjoyable but also safer: a dull knife is dangerous because it requires more force to cut, thereby sacrificing control. Avoid damaging your knife unnecessarily; use it only for wood and avoid metal, especially other knives. Protect the blade during storage and do not use it like a pry. Before the blade dulls and whittling becomes more difficult, strop the blade to fine tune the cutting edge, about every 20 carving minutes, depending on the hardness of the wood. If stropping doesn’t sharpen a dull blade, sharpen on a stone to repair or rebuild the cutting edge.

The Kirschen Schitzmesser (carving knife) comes new with a rough factory ground Murphy blade that must be sharpened on a stone before it is used on wood. Some knives come pre-sharpened, but eventually you’ll need to sharpen the blade yourself.

Stropping

Stropping is all that should be needed to keep a blade razor sharp for a very long time. Some carvers use leather strops without compound, but adding an abrasive speeds the process. Stropping compound is often used with suede leather but it can also be applied to smooth leather. Rub the abrasive into the entire surface of the strop. Repeat applications every fifth use; when the compound gets thick and crusty, remove it with heat and a butter knife. To strop a knife, lay it flat and apply firm pressure as you pull it backward across the strop. Keep the bevel of the blade flat through the entire motion. The cutting edge should slightly compress the leather, allowing the abrasive compound to sharpen the microscopic bevel at the edge. A trail of black residue should be left on the strop, indicating that metal is being removed. With coarse stropping compound, a few strokes on both sides will bring a dull blade back to razor sharp.

To prepare a leather strop with aluminum oxide powder, spread the powder evenly on the entire surface of the strop with the applicator.

Strop your knife by firmly pressing it flat and pulling it backward several times on each side across the leather.

Honing

When a blade has a bad factory finish, is nicked, or stropping fails, it’s time to hone. First, secure a 600-grit stone to a stable surface. Apply water to the stone’s surface and bring the blade to it. Using your hands on both the handle and the blade, lift the unsharp side of the blade about 1/32" (0.8mm) and stroke the knife on the stone backward on both sides until a tiny burr appears along the entire edge. Remove this burr by honing on a finer 1200-grit stone or on a leather strop; a bare piece of smooth leather works well for this.