6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

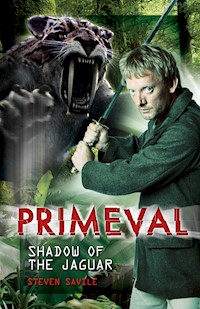

Strange anomalies are ripping holes in the fabric of time, allowing creatures from distant past and far future to roam the modern world. Evolutionary zoologist Nick Cutter and his team must track down and capture these dangerous creatures and try to put them back where they belong. A delirious backpacker crawls out of the dense Peruvian jungle muttering about the impossible things he has seen... A local ranger reports seeing extraordinary animal tracks and bones - fresh ones - that he cannot explain... Cutter and the team are plunged into the hostile environment of the Peruvian rainforest, where they endure a perilous journey towards something more terrifying than they could possibly have imagined...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also available in the Primeval series

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Acknowledgments

Also Available from Titan Books

Primeval Action Figures & Monsters

Also available in the Primeval series:

THE LOST ISLAND

By Paul Kearney

EXTINCTION EVENT

By Dan Abnett

FIRE AND WATER

By Simon Guerrier

PRIMEVAL

SHADOW OF THE JAGUAR

STEVEN SAVILE

TITAN BOOKS

Primeval: Shadow of the Jaguar

ISBN: 9781848568969

Published by

Titan Books

A division of

Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition March 2008

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Primeval © 2008 Impossible Pictures.

Cover imagery: rainforest © Shutterstock.

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Sarah and Lee

Consider this a ‘get out of Christmas and Birthday presents’ free card

For the next... ooh... five years.

With love

Bruv

ONE

The animal’s lonely voice haunted the mountainside. The melancholy sound rolled across the canopy of wet leaves and dripped down the trailing vines, all substance lost long before it reached the brothers’ ears. It did not matter.

The rainforest spoke with the tongues of Peruvian devils, a thousand sounds competing for attention, and beneath them a thousand more just as eager to be heard. The place was alive with the constant chittering of insects; the deep-throated rumbles of the yellow-backed toads; the raucous caws of the colourful birds as they preened and strutted on the high branches; the scuttle of tuco-tuco, sloths and opossum through the thick vegetation; the slithering of the lachesis muta through the thick grasses; the soft susurrus of the leaves and the silken rush of the rain falling down between them.

Even at dusk, everything was vivid and alive. But night was coming on fast beneath the thick, leafy canopy.

It was hot. Unbearably so. The cotton clung to Cam’s flesh. He plucked at it with sticky fingers. There was nothing comfortable about the cloying humidity. He ran his fingers through his hair. They tangled in a greasy knot that he couldn’t tease through.

“I’m telling you, Jaime, it was like shards of ice spinning lazily in the air.” Cam shook his head, knowing the words couldn’t come close to describing what he had seen.

“Right,” his younger brother said, a wry grin playing over his lips. “Clouds of ice in the middle of the rainforest, and you still say you’ve not been on the whacky baccy?”

“Give it a rest, Jaime. I’m serious. It was weird.”

“You’re telling me.” Despite his words, Cam could tell Jaime was intrigued. “Did you try and touch one? I mean, what was it like?”

It was the obvious thing to ask. It was precisely what he would have asked, if their roles had been reversed. Even so, he didn’t have an answer.

Cam peered across the fire at his brother. How could he admit that the strange phenomenon had actually scared the life out of him? He played the big tough guy, but the thought of reaching out and actually touching that eerie light sent a chill running the length of his spine.

“No,” he admitted, a part of him hoping that would bring an end to Jaime’s questions.

He picked up a stick and stirred the fire. The flames had almost guttered out, and they sprang back to life, throwing weird shadows across the small enclave within the trees. It quickly burned low again, its fuel reduced to charcoal. The shadows shrank, becoming hunched and cadaverous as they ghosted across the encroaching foliage.

Beyond them lurked thicker clusters of darkness; the stones of the ancient Incan temple they’d discovered. It was a loose term, discovered; it wasn’t as though they were the first humans to set foot in the place, but with the isolation and lack of anything approaching a beaten track it still felt that way.

With dusk drawing in they’d decided to hold off on exploring the ruin until morning. Without the luxury of electric lights, the risk of injury outweighed their curiosity. So they had bivouacked down for the night, with the promise of adventure waiting for them the next day.

In the fading light, they had gone to search for enough dry wood to start a fire — more as a deterrent to the insects than as a source of heat. That was when Cam had seen the peculiar light.

He picked up a piece of charcoal, which broke and smeared across his fingertips. It was potent stuff, the essence of life and death in one crumbling stick. As he stared at it, it appeared so mundane, and yet everything around him, even his brother, could be reduced down to this simple dust of carbon, and without it nothing could live.

He shook his head.

Jaime grunted, obviously far from satisfied with his brother’s evasiveness, but equally familiar with it.

“You weren’t in the least bit curious?” he pressed. “That’s not the Cam Bairstow I know and love. Hell, you almost sound like the old man. Gearing up for a career in politics, are we?”

“God forbid,” Cam replied, matching his brother’s grin. He brushed away the dirt at his feet and jammed the stick into the ground. Then he rooted around in his pack for his water bottle, uncapped it, and drained a long swallow of warm water. He missed the simple luxury of ice.

“I’m going to take a leak,” Cam said as he pushed himself to his feet and dusted off his hands on his shorts. “Try not to burn anything down while I’m gone.”

Away from the fire the air was thick with the hum of mosquitoes. One brushed against his face. The tickle of its wings reached his lips before it disappeared. A week ago he would have squashed it or swatted it away. A rash of bites later he’d wised up to the fact that dead mosquitoes only drew more. Now he was content to let it explore the warmth of his face and move on in its own good time, trusting the mosquito repellent to live up to its name.

Cam pushed aside a trailing branch and the leaves closed around him as he moved further away from the safety of the fire. Within a dozen paces the trees became so thick that the night lost all definition, and turned black. The deadfall on the ground crunched beneath his feet as he blundered forward blindly, reaching out until he found a thick-trunked tree. He unbuttoned his shorts, grunting contentedly as he relieved himself against it.

For a long moment Cam felt inconsequential beside the sheer size of the Amazonian giant. It was a lovely moment of role-reversal — now he was the mosquito, grateful that the tree couldn’t squash him.

If a man urinates in the rainforest and there’s no one around to hear it, does it make a sound? He chuckled at the thought. His mind had started running off on so many bizarre tangents recently; a symptom, no doubt, of being a million miles from civilisation, with only monkeys, tree rats, and his brother for company. After a month in Madre de Dios, an ecology reserve in the heart of the Peruvian rainforest, he ranked all three on roughly the same level of the evolutionary scale.

One by one the natural harmonies of the rainforest fell silent, until there were only the sounds of the rain in the high leaves and his urine puddling at his feet.

Cam buttoned up.

Something was wrong.

He knew it instinctively. Some primal part of his brain responded to the sudden silence. The rainforest was a living thing. For it to suddenly fall still could only mean one thing: there was something out there in the dark that had scared off the fauna.

“Jaime?” Cam called.

His voice cracked. He shook his head, smiling at the silliness that had him spooked by simple silence.

As though in answer, he heard a brief rustle of movement, the tangled scrub shifting as something heavy prowled through the darkness. He turned in the direction of the sound, but there was nothing to see. Blinded by the darkness, he tried to follow the sound with his ears instead.

“Jaime, stop playing silly beggars. It isn’t funny.”

Though he was hopeful that it was his brother, Cam couldn’t bring himself to raise his voice. Something told him that wouldn’t be a good idea.

This time, a low-throated growl rumbled close to his ear. It was a predatory sound filled with the resonances of the hunter stalking its succulent prey. Cam spun around, certain the animal was at his shoulder, but it was nowhere to be seen.

Off to his left, the sharp crack of breaking deadfall snapped his already shredded nerves. He peered frantically at the layers of darkness that lay beyond the leaves.

“Jesus,” he muttered, breathing hard. “Pack it in, Jaime.”

His heart hammered against the cage of his ribs. Warm beads of perspiration trickled down the curvature of his spine. It didn’t matter that he couldn’t see anything; he could feel it. He wasn’t alone.

And he knew it wasn’t his brother.

There was a distinct rhythm to the movement, like something moving on all fours, close to the ground. He was put in mind of a cat, circling its prey; which made him the mouse.

Cam cursed himself for not bringing a torch. Suddenly the safety of the fire felt a long way away.

He dared not move.

“Jaime,” he said, very quietly, willing it to be nothing more than his brother, playing the fool.

The animal moved through the darkness slowly, its passage a threatening whisper as it brushed against the vines and leaves.

And then it was gone — the beast moved on. He was alone with the oppressive silence.

Strangely, that was worse. At once the rainforest felt incredibly claustrophobic, the towering trees and dragging branches pressed in on him, heightening the sound of the rain on the canopy of leaves. It lent the night a nightmarish quality. The chill of dread settled beneath the trickles of sweat pouring down his skin.

“Jaime?” Cam called again, but there was no answer.

Suddenly the darkness erupted with the sounds of violence. And he heard his brother begin to scream.

Cam started to run, blundering through the trees blindly, feeling as if he was moving in slow motion. He pushed aside branches that clawed at his face, ducking beneath the sting of barbs and thorns. His brother’s shrieks were sickening.

Worse, though, was the sudden hush that followed them.

“Jaime!” Cam shouted, bursting out of the trees.

The campfire lay scattered, faggots of wood smouldering, barely casting enough light to hold back the night. Still, it showed too much.

His brother lay on his back amid the ruin of the fire, dark stains all across his body where his flesh had been torn open by tooth and claw. The savagery of the attack was writ in blood and shadow. Cam took an unsteady step forward, unable to wrench his eyes away from the sight of his brother’s broken body, all thoughts of Incan ruins suddenly far, far away.

Before he could take a second step a huge muscular creature hit him, the sheer momentum of its attack hurling him into the underbrush as huge teeth snapped and snarled at his face.

TWO

The call came in at midnight, the voice on the other end of the line summoning James Lester to the Under-Secretary’s residence. He knew better than to question the venue or the hour: the more powerful the man, the less he slept.

Lester dressed quickly, adjusting the lie of his bespoke waistcoat and teasing the knot of his plain silk tie. Appearance was everything. He shrugged into his jacket and then into his topcoat, and walked out to the waiting car.

Miles, his driver, nodded and opened the rear door for him. The interior was pleasantly warm against the chill of the night; Miles had obviously set the heater running while Lester had dressed again.

“Where to, sir?”

“The Under-Secretary’s in Belgravia.”

“Very good, sir.”

London might not sleep, but it most certainly dozed, Lester thought as the car left the South Bank, swept over the Thames and turned onto the Strand. The quiet street was bathed in the yellow glow of the lights. The legal district was dead, though some of the usual tourist spots were still isolated hives of life.

Peering out into the night, he was sure some pseudo-scientist must at that very moment have been studying the social strata of the city, and drawing the same conclusions as the anthropologists studying the apes of deepest darkest Africa. Man was, after all, a beast. The city at night showed just how little the species had truly evolved. And of course, it boasted other denizens, populating the darkness that surrounded the pubs, clubs and restaurants.

It was a different breed that came out after dark. The street people, invisible during the day, could be seen huddled in their doorways wrapped in blankets and newspapers while the twenty-four-hour party people danced, drank and acted as though they owned the city. They had all the rituals of their jungle counterparts, banging their chests to attract a mate.

It was all quite pitiful, really.

The car negotiated the kinks around Charing Cross and took the turn onto Pall Mall. Here the street retained much of the dignity it must have known in the days of Gentlemen’s Clubs and hansom cabs. Even this late at night the immaculately tailored doormen stood beside the gleaming porticoes, playing guardian to the last bastions of entitlement. Behind those doors lay other worlds of charm and old money. Those portals were, Lester thought wryly, every bit as paradoxical as any anomaly that opened into the Permian. Polite society had its own magical rifts that only a certain class of traveller was allowed to enter, where the hoi polloi were about as welcome as a plague of locusts.

They turned right on St James and entered the heart of Belgravia.

Sir Charles Bairstow’s residence was a three-storey Edwardian townhouse in a narrow mews. Within a hundred yards it was as though they had driven into the land that time forgot. Everything was transformed, right down to the faux-gas street lamps and the planters dripping colourful lavender bougainvilleas, their petals like tissue-paper flowers.

Miles pulled up to the curb, and kept the car idling while Lester clambered out. Standing on the pavement, he looked both ways, not really sure what he expected to see.

The street was empty.

He walked up to the door and rapped on it, using the lion-headed brass knocker. The noise was shockingly loud in the quiet residential street, like the report of a gun, or a car backfiring. Lester winced, half-expecting a dozen curtains to twitch in response.

He heard someone fiddling with the security chain, and then the latch, before the door opened.

Bairstow’s housekeeper peered myopically out into the dark street.

“James Lester to see Sir Charles,” Lester said, adjusting the knot of his tie. “I’m expected.”

“Yes, yes, come in, Mr Lester. Sir Charles has retired to the smoking room. He is expecting you. May I take your coat?”

Lester entered the warmth of the old house, wiping the soles of his shoes on the mat despite the fact that he knew they were immaculate. He gave his topcoat to the old woman, who said, “Second door on the left, on the first landing.” She nodded toward the narrow stairs.

Before proceeding, Lester took a moment to look around, taking in the impracticality of the thick champagne pile of the carpet, the ostentation of the heavy chandelier, and the delicacy of the armoire. Several large oil paintings lined the stairs, the familial resemblance obvious in each, from the current Sir Charles at the foot of the stairs all the way back through the generations to wigged ancestors along the landing.

Another anomaly.

Lester nodded to the housekeeper and went up.

A night-light illuminated the landing. The second door was slightly ajar. He pushed it open and entered.

The old man was sat in a wing-backed Chesterfield armchair with his eyes closed. Logs crackled and spat in the open hearth, the fire providing the room’s only light. This chamber was the living embodiment of Victoriana, with antique maps and leather-bound books decorating the walls, the bookcases augmented with a variety of mounted animals and other curiosities. A glass-fronted cabinet contained various lepidoptera specimens, their thin membranous wings providing a splash of colour to the dour setting.

Lester coughed politely into his hand.

Sir Charles Bairstow was as much a throwback to those quintessential times gone by. He sat beside the fire in his plush smoking jacket, a thick cigar clutched between equally thick fingers. Ash gathered in the small silver tray balanced on the arm of the chair. He had silver-grey hair and thick bushy mutton-chops. All of his sixty-one years were etched deep into his face as he opened his eyes.

“Ah, James, come in, come in.” The old man gestured toward the second empty armchair.

“Sir Charles,” Lester said, joining him beside the fire. Bairstow looked tired; more so than the hour accounted for. This was a weariness that had been ground in over days. He recognised the symptoms of insomnia in Bairstow’s eyes and the pallor of his skin. Dark shadows followed the line of his jaw, suggesting that it had been more than a day since he last shaved. Still, he maintained an air of dignity, despite his exhaustion.

“Care for a snifter?” Sir Charles unstoppered an ornate crystal carafe filled with amber brandy, and poured himself a finger’s worth into his equally ornate glass.

“It’s a little late for a social call,” Lester observed.

“Indeed, but we are civilised men, James. We can conduct our business with a modicum of decorum, no?”

Lester inclined his head in agreement.

Sir Charles filled a second glass and pushed it across the table. Lester picked it up and cradled it in his hand, swirling the rich liquid gently against the sides of the glass before lifting it to his nose and inhaling. The fumes alone were intoxicating. He sipped the brandy and set the glass aside.

“I take it there is a reason for the hour, and the location?” he ventured.

“Indeed,” Sir Charles said, leaning forward in his chair. “It’s all very clandestine, I know, but I would ask a favour of you.” The way the old man said “favour” left Lester in no doubt that he was about to be asked for the sort of favour he could not refuse.

“Do you have children, James?” Bairstow asked.

“Three,” Lester said.

“Ah, then you will understand, I am sure. I have two sons, Cameron and Jaime. They are of that age, idealistic, with a fire in their bellies. You know how it is.” Lester nodded. “We had them late, spoiled them completely, of course, like most old parents. They were our little miracles.” Sir Charles’ focus seemed to drift into nostalgia. There was obviously something he wanted to say, and it was equally obvious that he didn’t actually want to say it.

“Cameron recently graduated in archaeology from Cambridge, Jaime is about to enter his final year. In this day and age, even an honours degree is not a guarantee of a job, and archaeology is not what anyone would call a lucrative career, so Mae and I thought it wise to give the boys a leg up. It is all about experience, after all. A man is no more than the sum of his experiences, and all that.”

“Absolutely,” Lester agreed, savouring another sip of the ludicrously rich brandy.

“Do you know how fiercely competitive it is, this digging up of old bones? And for what, exactly? The opportunity to sleep in a tent and live on ramen noodles?” He said it in that ‘boys will be boys’ manner adopted by fathers the world over.

“Quite,” Lester said. He glanced at his watch; then tried to mask the gesture a moment too late.

“Ah, I’m boring you,” Sir Charles said. “My apologies. I’m an old stick-in-the mud, I’m afraid. I don’t understand all of this fascination with bones and broken stones.”

“Something about those who don’t understand the mistakes of history being doomed to repeat them, perhaps?” Lester offered. “Now, tell me about this favour.” His only hope for sleep was to get the old man back on track.

“Yes, yes, of course.” Sir Charles looked pained that the conversation had steered itself back around. “We arranged for the boys to travel to Peru. They flew into Lima, and then moved on to Cuzco. They travelled from there to the rainforest in the region known as Madre de Dios — the Mother of God. It’s a nature reserve, one of the few in the world that harbour so many truly endangered species, as well, of course, as fabulous Incan ruins.”

“Sounds like a dream holiday,” Lester said. But the expression on Sir Charles’ face indicated that he did not agree.

“James, it’s been six days since anyone has heard from either of them, and nothing is being done about it.” His voice was low and firm. “The Peruvians are being deliberately pig-headed. No one will tell me anything, and as far as I am able to ascertain, there are no search parties out looking for the boys. Madre de Dios is rife with poachers; ruthless men who hunt these dying species and sell their hides to the highest bidder.

“I will not allow my boys to simply disappear off the face of the Earth, I may not have been the best parent, but I am still their father.”

“And you think the boys might have run afoul of these poachers? Surely there may be another explanation. As you said, boys will be boys. Perhaps they found themselves a nice pair of señoritas, and are holed up in a hotel in Trujillo drinking pisco sours and dancing the nights away.”

“No, I don’t believe that for a moment. It isn’t like them to be out of touch. They know how much their mother worries.”

“Nevertheless, I don’t see how I can help you, Sir Charles. Surely you’d be better off talking to someone in the Foreign Office. Strings can be pulled.”

The old man leaned forward in his chair, his expression suddenly intense as he steepled his fingers. The gesture was somewhere between a prayer and an act of begging.

“Anything official becomes a diplomatic incident, James. You know how the system works. The Peruvians are investing more money than they can afford in promoting the region as an eco-resort. If anything threatens those investments, they’re likely to bury the truth, whatever it may be, and Number 10 won’t stand for too many waves: the entire eco-resort is being underwritten by British Insurance firms, and financed by a conglomerate of British banks. We’re talking bad business, James. No one wants adverse publicity.

“If something has happened to the boys...” He let the possibility hang there, not wanting to finish the thought.

“Still —” Lester began. But Sir Charles cut him off.

“There must be a way for your department to help me, James. Your men are scientists. I was thinking that you might mount an expedition? No need for political red tape, doesn’t arouse suspicion at home or abroad to have a few scientists doing research, and therefore much easier to get the necessary visas from the Peruvians.”

“That’s out of the question, I’m afraid,” Lester said, shaking his head. He didn’t even want to consider the ramifications of what the Under-Secretary was asking.

“Please.” The old man stared at him.

“Sir Charles, we have no remit for work overseas, and mercifully no proof that our research has any relevance beyond the natural boundaries of the British Isles.”

“Then you will not help me?” The shadows beneath his brows seemed to deepen.

“I’m sorry. You should talk to your counterpart in the Foreign Office, sir. Perhaps we have operatives in the area, or close by. I can’t imagine the Prime Minister would countenance such heavy investment from our own economy without at least a few eyes watching the pot. Eyes everywhere, and all that.”

The old man seemed to deflate in his chair, the stiff upper lip crumbling visibly.

“I could order you,” Sir Charles said then, a last ditch gambit.

“If that were true, we wouldn’t be meeting like this. We would be in Whitehall.” Lester rose from his chair, setting the empty glass on the table. “Goodnight, Sir Charles. I hope you hear from your sons soon. I truly do.”

“But you won’t help.” It wasn’t a question, so Lester didn’t answer.

He left the old man by the fire, well aware of the fact that by saying no he had almost certainly made his life more difficult.

It was a little after two when he clambered back into the waiting car. That left him with less than four hours sleep. Instead of returning home, he had Miles drive him to the Anomaly Research Centre. He could catch an hour or two in the ARC lounge, if needs be.

Professor Nick Cutter was woken by the electronic voice telling him that he had mail.

He rolled over groggily.

Cutter had fallen asleep on the couch in his office. It still didn’t feel like his office, though — he was used to the clutter he had accumulated over years of study and hoarding. This place felt more like a laboratory than a place for thoughtful contemplation.

He yawned and knuckled the sleep out of his eyes before he forced himself to sit up. Everything ached.

The ambient light replaced the passage of time with a constant illumination; it was never night in the Anomaly Research Centre.

He stood and stretched, working the kinks out of the muscles in his shoulders and lower back. Though only in his late thirties, and reasonably fit, he still felt joints popping. Sleeping on the couch is for a younger man, he thought wryly.

His stomach grumbled. He had no idea what time it was, he realised, or how long it was since he had last eaten, and even then it had only been a slice of Apple Danish washed down by a cup of tepid coffee. Deciding the email could wait, Cutter went in search of sustenance.

His footsteps echoed hollowly as he walked across the cement floor of the loading bay, the quality of the echo changing as he entered the corridor of offices and laboratories that led down to the team’s rec room.

He caught a glimpse of himself in the glass of the vending machine, and ran his hand through the dark blond rat’s nest he called hair, trying to bring it to its normal sense of order. Then he fed a handful of coins into the machine and punched in the code for a multigrain nutritional meal supplement bar that sounded both healthier and tastier than it was, and a diet caffeine-free low-sodium soda that was essentially fizzy water. Collecting his bounty, Cutter headed back toward his office.

Re-entering the loading bay from the other side, he saw that the light was on in Lester’s office. The man was a bureaucratic machine. Cutter watched a shadow move against the wall, but didn’t see Lester himself. Shrugging, he wandered back through to his own office, peeling back the foil on his multigrain treat and eating half of it before he sat back behind his desk.

The computer screen had fallen asleep. Lucky bastard. He pushed the mouse to wake it.

He opened the mail box and saw that he had three messages flagged as new, one from Lester, another from someone distinctly fictional promising increased length and girth for only ninety-nine dollars, and the last one from someone called Nando Estevez. Cutter recognised the name in that vague I’ve met you at a function or somewhere kind of way.

He popped the tab on the can and drank a mouthful of too-cold soda.

Opening the email, he read through it twice; then sat back in his chair.

Even with evidence in black and white, it took him a moment to associate “Nando” with Fernando Estevez, a student of his from almost ten years ago now. All sorts of ghosts come back to visit, sooner or later, he mused darkly. But he remembered Fernando well, a short, serious young man, gifted with a fearsome intelligence that was only held back by his blatant disregard for grammar and spelling. That, at least, seemed to have improved marginally over the years that had passed since he had last read his student’s essays.

But this was no essay, and even a third reading left him with a growing sense of concern.

From: Nando Estevez <[email protected]>

Date: May 17, 2008 4:44:28 AM GMT+01:00

To: Nick Cutter <[email protected]>

Subject: Behaviour and Bones

Dear Professor Nick Cutter,

It is me, Nando Estevez!

I am sure you remember me. It has been a long time for both of us, but how could you forget old Nando?

I would ask for your help in something. I think, perhaps, you will find it very interesting, and very mysterious.

After graduating your class I took a job along with Esteban, my half-brother. We worked for a few years off the coast of Trujillo on a marine expedition. It was fascinating work, though I must admit it was mainly to impress the girls! But all good things come to an end, they say, and recently we began working in the new nature reserve at Madre de Dios. The work is sadly less impressive with the ladies, but it is far more interesting for us!

There are things happening in the reserve that I do not understand. In fact, they make very little sense when I think about them.

It is my job to identify the various species that dwell in the reserve, to tag them and follow their movements and record their habits. We have a great variety of rare animals like the capybara, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, and the giant river otter, Pteronura brasiliensis. It is a zoologist’s dream!

Now, to the crux of the matter, the animals have been behaving strangely, you see. Their patterns no longer match our expectations, even considering for the increase of poaching and the threat of mankind. All I can think is that something else is causing this peculiar behaviour.

Only this week I have identified several tracks that should not be here. I am confused by them, yet I do not wish to mention this to anyone for fear they will think I have gone mad. These are tracks and bones that do not make sense. There is no one I can trust with the secret I believe I have found. For I have checked all of the books, and the only conclusion I can find makes no sense.

Who could I show the bones to? Who would believe that these fresh bones are also old bones? Who would believe me if I said I thought they were from the Plio-Pleistocene perhaps, or even earlier, but show no signs of fossilisation? The marrow in the bones is fresh.

It seems absurd to me that these strange bones and wrong tracks would be here now, and with my animals behaving so strangely. I fear I am losing my mind! My number at the resort is 84235151, with the Peruvian prefix, 0051 from England. Please call me, Professor Nick!

Your old student,

Nando Estevez

Cutter set aside the soda can and stared.

His first instinct was to dial the number and press his old student with a dozen questions about the nature of these tracks, and his suspicions about the behaviour of the indigenous fauna. Cutter felt a tingling thrill of excitement at the possibility that what he was looking at was proof of the first anomaly off the British mainland.

The implications were massive.

His second instinct was to call the team in and share the excitement. However, he didn’t succumb to either urge. Instead, Cutter opened a web browser and entered ‘Madre de Dios’ into the search function.

A lot of the pages the search returned were either religious in nature, illuminated with iconic images of the Virgin Mary cradling the baby Jesus, or they were written in Spanish. Refining his search to provide English-language results only, Cutter trawled through the rest for the better part of an hour, finding miniscule maps he could barely read and spectacular scenic photographs of the Amazon rainforest and the misty peaks of Machu Picchu.

The first non-religious hits were all for the same sort of stuff: trail tours for Incan ruins, Kon Tiki rafting trips and dream vacations in the Andes, and they were followed by virtual tours and the wiki page for the region. ‘Biobridges.org’ provided him with a list of the research stations such as the one to which Nando and his brother had been assigned.

Deeper into the search he found a host of Inca ruins, some so breathtaking they looked like oil paintings of imaginary places. He wasn’t particularly interested in the old stones, though — it was old bones that piqued his curiosity.

Since the rest of the ARC team wouldn’t arrive for quite some time, he had time to kill, and ran various searches on South American fauna using a variety of keywords, one being ‘Plio-Pleistocene’.

The results were even less encouraging than the initial search, though more Darwinesque than intelligent design: hominin evolution in the Amazon basin, climate change and glacial shifts, volcanic history of the region, geological abstracts on the Madre de Dios River and the clay strata, and even a paper which promised paleomagnetic evidence of a counter-clockwise rotation of the Madre de Dios archipelago in Chile.

He paused for a moment and glanced at the clock in the top corner of the computer screen. It was barely a quarter to six — which, according to the time and date function on the computer, meant that it was almost midnight in Lima. Too late to call Nando, and it would still be a couple of hours until the others rolled in. So he contented himself with printing off any articles that seemed even remotely promising. There were times when he still preferred paper to electronic files.

He tried a blog search next, using one of the many web crawlers that trawled through the inanities of the world’s everyday lives. Most were glorified diaries for public consumption, and they were very much the modern disease, reflecting the Average Joe’s need to prove that his life had genuine meaning, and that had its advantages. But every now and then there were hidden nuggets of gold to be found in the blogosphere, so once again Cutter ran through a number of keywords, looking for anything that even vaguely hinted at a South American anomaly.

Every one drew a blank.

He didn’t know whether or not to find it reassuring. After all, that didn’t mean there wasn’t an anomaly out there — only that no one had seen it.

So he left the computer and wandered across to the window that looked onto the loading bay. There were no windows opening out of the ARC into the world at large — more to stop people from looking in than to stop the staff from looking out — and it lent the facility an oppressive feel. He braced himself on the sill.

It still seemed so alien.

There were times when it was difficult to reconcile himself with the fact that evolution had taken the slightest of nudges, and drifted askew just enough for this pseudo-military government establishment to exist. Stranger yet, everyone else seemed to feel so natural with it.

The world around him had changed without anyone realising it. Anyone but him.

Cutter clenched his fists.

Thinking about it just left him feeling frustrated and angry, and not a little guilty. He had stepped out of the rift with Helen, thinking... what? Cutter laughed bitterly. Thinking just brought it all back, and for however long he thought about it, it didn’t matter that the affair had happened a decade ago.

But that way lay madness. So many ifs, buts and maybes. Cutter pinched the top of his nose, furrowing his brow.

He was hungry again — or rather, hungry still. There was a greasy spoon not so far away, and he could do with the air and to stretch his legs. The email would still be there when he got back.

There was smoke rising through the trees. It was thick, black, cloying stuff that carried with it the reek of cooking meat.

Cam Bairstow staggered down through the smothering vegetation, tripping and stumbling along a path that wasn’t there, his eyes fixed desperately on the one sign of civilisation he had seen after days and nights alone in the jungle. The smoke meant hope. He was dizzy from dehydration, exhausted and weak from blood loss, but his cuts had begun to clot. Now it was all about food and water.

The fragrance flavouring the smoke was irresistible.

Cam stumbled on blindly.

While he was lost within the trees, time had become a meaningless concept. There was no day or night, only shadows and darker shadows. His heart hammered erratically now, and his vision swooned as he hit the bole of a thick trunk. The flair of pain in his shoulder reignited the fire in a dozen of his wounds, and a croaking cry escaped his swollen lips.

He couldn’t remember anything of the last few days. He had woken into a world of blood and hurt. He hadn’t moved for the longest time, allowing the pain to own his flesh. There had been sounds all around him as he opened his eyes, and he had thought that odd. The last thing he remembered had been silence. Complete and utter stillness.

But that couldn’t be right. The forest was never still. Never silent. It was a living thing.

Then he remembered the screams.

Somehow he had staggered away from the ruined temple, but he had been too weak to risk the rope bridge, and instead had slipped and fallen and skidded and slid down the side of the long mountain toward the ravine, his eyes fixed on the crystal blue water. The trees offered him some protection from the elements, though a mist had risen thickly to engulf the world around him, leaving Cam to blunder down until he reached the bottom.

Images of death formed within the curls of mist, and faces formed in the thick white. He saw again and again the last few seconds before the creature’s attack. It brought back the pain with a shocking clarity. And the pain brought something else in turn, a hollowness at the memory of Jaime’s body lying there, a mess of blood in the dirt of the forest floor.

His foot caught on a ragged spur of root.

The plant snagged Cam.

He fell sprawling into the dark loam of the forest floor.

He lay there on his back, too bone-weary to move, knowing that if he didn’t locate that reserve of strength needed to carry him to the village, they would be finding his bones. Nothing more.

Above him a stripe-faced monkey swung through the canopy hand-over-hand in a looping, easy motion, working its way down through the branches. The animal was skittish, swinging quickly from perch to perch and leaving rustling leaves in its wake. Cam watched it, wishing for a moment that his life might be that uncomplicated — but it was in a way. It had been reduced to the most basic of elements — stand up and walk, or lie there and die.

He didn’t move because death didn’t feel like such a bad place to be.

Then the scent of the smoke — ugly and abrasive — entered his lungs, seeping down his throat, but it was also a glorious sensation, one filled with hope. The meat that was flavouring it was sickly sweet. The odour clawed at his empty belly, reminding him how desperately hungry he was.

He pushed his hands beneath him and tried to stand. He was like a new-born calf, struggling to balance on shaky legs as he rose and stumbled on between the trees. More than once he was forced to use their trunks for support.