Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

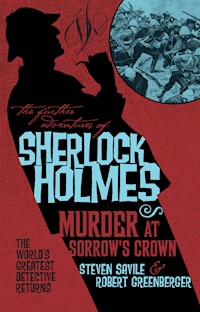

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

A frantic mother comes to 221B Baker Street, begging Sherlock Holmes to find her son. A naval officer posted to HMS Dido, he was part of the Naval Brigade that joined the Natal Field Force to fight the Boers. But he did not return with his men, and is being denounced as a deserter. Can Holmes and Watson uncover the truth, a truth that threatens the very fabric of the British Empire?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 403

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Available Now from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

One: A Taste for Ash

Two: A Bureaucratic Wall

Three: Rearranging the Attic

Four: Tea with Lord Rowton

Five: Rescued by Wiggins

Six: Cutting to the Chase

Seven: Recruiting Wiggins

Eight: The East India Company

Nine: A Visit to the Club

Ten: A Trip to Newcastle upon Tyne

Eleven: A Rematch with a Killer

Twelve: Mining in Pretoria

Thirteen: A Summons from Gregson

Fourteen: Locating the Mine

Interlude

Fifteen: Murder Most Foul

Sixteen: Declassified

Seventeen: Bringing Justice to Light

Eighteen: The Man in Black

Nineteen: Peace

About the Authors

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKSTHE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES:

THE COUNTERFEIT DETECTIVE (October 2016)Stuart Douglas

THE ALBINO’S TREASUREStuart Douglas

THE DEVIL’S PROMISEDavid Stuart Davies

THE VEILED DETECTIVEDavid Stuart Davies

THE SCROLL OF THE DEADDavid Stuart Davies

THE WHITE WORMSam Siciliano

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERASam Siciliano

THE WEB WEAVERSam Siciliano

THE GRIMSWELL CURSESam Siciliano

THE ECTOPLASMIC MANDaniel Stashower

THE WAR OF THE WORLDSManly Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE SEVENTH BULLETDaniel D. Victor

DR JEKYLL AND MR HOLMESLoren D. Estleman

THE PEERLESS PEERPhilip José Farmer

THE TITANIC TRAGEDYWilliam Seil

THE STAR OF INDIACarole Buggé

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRARichard L. Boyer

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES:MURDER AT SORROW’S CROWNPrint edition ISBN: 9781783295128E-book edition ISBN: 9781783295135

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 201610 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2016 Steven Savile & Robert Greenberger

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:www.titanbooks.com

I would like to dedicate the Great Detective’s latest case to Miranda Jewess who made a most excellent Watson to my and Bob’s Sherlock—Sorrow’s Crown would not be half the book it is without her red pen. Scratch that, she’s more of a Mycroft, two steps ahead and looking out for us boys. Thank you, boss. We owe you.

STEVEN SAVILE

I would like to dedicate this adventure to Steve, who went from friend to partner. He stepped in to help shape a notion into a novel and did so with verve and patience. And a huge thank you to Miranda who saw to it we had the time and offered us the guidance to make this a worthy read. I owe you both.

ROBERT GREENBERGER

“A sorrow’s crown of sorrow is remembering happier times.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson

Prologue

As celebrated as Sherlock Holmes was around the cusp of the twentieth century, a number of his investigations were deemed sensitive to national security. The Official Secrets Act of 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 52) denied his companion, Dr. John H. Watson, the opportunity to publish the most fascinating and uncomplimentary details of those investigations in any of the popular magazines that would usually carry the exploits of the great detective, and resulted in a number of his diaries being confiscated by the authorities. There was one such case in the summer of 1881, that was subsequently suppressed by agents of Her Majesty’s Government, the ramifications of which were felt the length and breadth of polite society, highlighting the need for a new Act of Parliament.

It is only in recent years that these investigations have been declassified, the secrets contained therein finally deemed safe for consumption by the general public whose appetite for such exploits remains insatiable.

What follows is the unaltered account of one such investigation that is of interest, perhaps, because of the tarnish it adds to the government’s reputation during what was a particularly volatile period in our country’s history.

One

A Taste for Ash

Being an Account of the Reminiscences of JOHN H. WATSON, M.D., late of the Army Medical Department

Our lodgings reeked of ash. It was a distinctly acrid tang that clung to the air with all the tenacity of a flesh-eating parasite, that is to say—and with an Englishman’s natural tendency for understatement—it was quite unpleasant.

While Sherlock Holmes and I got on well from the outset, I must admit that living with him was a series of constant adjustments. Mine, not his. Sherlock was a man very much set in his ways and I was expected to come around to his way of thinking in all matters. Shortly after agreeing to room with him at 221B Baker Street, he had settled in, taking one of the bedrooms for himself while commandeering much of the large, airy sitting room with his boxes and portmanteaus. While it took me the matter of the evening we agreed to lease the space to bring my things around, it took Holmes much of the following day. After that, he took his time setting things up, caring more for his weights and measures, his chemical and microscope slides, than his personal belongings.

During those first few days and weeks he spent the majority of his time at his chemistry table, though increasingly he came to spend more and more time in the sitting room, fussing with one thing or another and taking careful notes with the rigid fascination of an obsessive. Any post that arrived for him tended to be overlooked, tossed into a corner. After several days the stack of letters transformed into a careless heap, and it became increasingly obvious he intended to ignore it until it became a bother to navigate. Not that either of us received much in the way of actual correspondence. I was on the outs with my brother and my parents were long since dead. Most of my acquaintances remained in the armed forces and were busy with their duties to the country. Holmes, however, subscribed to several newspapers, which were cast aside as he lost interest in their grim tales of life outside the window of 221B, and as far as I could tell, he did not seem to engage in much in the way of personal correspondence.

Despite his foibles, as lodgers went he was relatively easy to get along with. His routines were fairly set: he rose early and rarely stayed up beyond ten at night. He did not drink and it was not for some time after we settled in together that I was even aware that he owned a fine violin, he played it so seldom. The music he made when left on his own defied description, but he could, upon request, successfully recreate established works, such as my preference for Mendelssohn. In fact, while I was out trying to build up a viable medical practice for myself, he was either fixed on some scientific study or lying prostrate on our couch, deep in thought, still as a statue for hours. It was at these times that Holmes was at his most enigmatic, barely moving and never explaining himself to me. I will admit that upon returning to our rooms that first time I had thought he was dead. The man had not moved so much as a muscle in the six hours I had been gone. Six hours! I could never begin to guess what thoughts could occupy him so completely and utterly, but invariably he concluded his contemplation and snapped up from the couch to resume his studies without comment.

On other occasions, Holmes would leave 221B without a word or explanation of his plans and be gone for minutes or hours. His comings and goings defied any pattern and upon each return he never disclosed his whereabouts. Occasionally he would return with a package or two, something wrapped in used newspaper, but I never saw the contents, and presumed they were materials for his never-ending experiments.

I knew he was brilliant. That much was obvious, even then. A true one of a kind, and mercifully so. I would not want to imagine a London filled with Sherlocks. When we met he was already building up a reputation with the agencies of the law as a “consulting detective”, using his obsessive method of examining the world to assist on seemingly impossible cases. As a result, by July of 1881 he was already making something of a name for himself with Scotland Yard and the good men of the Metropolitan constabulary. Even the newspapers were beginning to acknowledge his existence, although they were yet to fully credit his contributions to the successful conclusion of those cases.

Personally, I was never less than astonished by his studied brilliance, though I must admit that I was becoming increasingly aware that as ferociously intelligent as he was with chemicals and matters of science, he was equally deficient when it came to matters of culture or politics. If the Queen’s image was not everywhere, I think he would have had difficulty coming up with her name, never mind her royal house. His memory was, dare I say, filled with more important things. He was a man without peer, using that intellect and rigorous scientific method to solve puzzles that baffled Scotland Yard’s finest. Building his skills through observation and practice, dating back to his brief two-year stay at university, had made him an extraordinary observer of the physical world around him. What he could tell from a smudge of mud or chip of paint never ceased to amaze me or impress those new to his acquaintance. Little wonder inspectors such as Lestrade and Gregson had come to call upon his services with increasing regularity. I’d noticed a pattern developing in those periods between cases when Holmes would manically begin a series of studies, throwing himself into the pursuit of knowledge with a single-mindedness that crossed well over the border of obsessiveness, hence the reek of ash currently wafting out of the sitting room.

I assumed it was a particularly strong cigar, and made a deduction of my own: we had a visitor. I dressed hastily and opened the door to find Holmes bent over a clasp which suspended a thick, dark cigar a bare sixteenth of an inch off the table, a glass dish sat snugly in a recess beneath to catch the ash as it burned merrily away, filling the room with a robust aroma.

We had no visitor.

“What in the world are you doing?” I asked him by way of morning greeting.

“I should think it’s perfectly obvious, Watson. I am watching this cigar burn.”

“Let me rephrase: why are you watching that cigar burn?”

“A better question,” he replied. “New cigars are imported all the time and each, quite obviously, has their own unique characteristics, including aroma and the properties of their ash.” I raised a questioning eyebrow, but didn’t say a word. Holmes continued, “As these new leaves enter circulation and increase in popularity, I need to know what sets them apart from similar cigars so as not to be fooled into drawing the wrong conclusion.”

“Of course,” I said, as though it made perfect sense.

“This latest shipment was just delivered to the docks this morning. I have one of my street Arabs always on the lookout for interesting and exotic imports on my behalf. He secured a handful of these, just in from Honduras, and here we are.” He gestured towards the contraption that held the smouldering cigar. “What better way to spend a damp, dreary morning than working with something new?”

“I can think of a few,” I offered, but he ignored me. One thing that we did not share was a sense of humour.

“See here. What do you notice?”

“That it might take some time before the odour leaves our rooms because the windows need to remain shut,” I replied, admittedly with some annoyance in my voice. I did not smoke cigars and this was a particularly strong example. The summer’s unusual heat should have meant the windows remained open for ventilation but Holmes’s experiment would have been diluted from whatever aromas wafted in from the still air outside 221B.

It wasn’t the answer he was looking for. Indeed, Holmes seemed bothered by the flippant remark as if I was not taking his studies as seriously as he did, which admittedly, I wasn’t. “Other than that, Watson.”

To appease him, and to give me something to do now that I was awake and dressed, I peered at the burning cigar, trying to understand how the leaves were wrapped and if the burn rate appeared unusual in some way. I did not know much about the murky world of cigars beyond the most elementary: that the cigar itself consisted of three distinct parts, the wrapper, the binder and the filler, and that if the filler was packed too tightly it blocked the airways through the leaves and if it were packed too loosely the smoke would burn too quickly. As I said, not a lot. Truth be told, dear reader, I doubted I would ever look at the world the way Holmes did and felt I would always be a bit of a disappointment to him. Still, I did my level best to distinguish some sort of anomaly in the ash.

“The ash appears longer than I am accustomed to,” I replied, hoping I had made a correct observation. Despite my best efforts and own scientific and medical training, I was always missing some detail that made me a constant inferior to my companion.

“Quite right,” he agreed, validating my conclusion for a change. “These are expensive compared with the penny cigars the common man might smoke. The higher quality is found in the leaves for both the wrapper and the contents. As a result it produces a much denser ash, which takes longer to drop.”

I could only stare at him, unsure of how this added to his store of knowledge.

“Why is it important? Because ash length changes the flavour of the cigar. A longer column of ash cools and ‘softens’ the smoke, making for a more pleasant experience, but is also indicative of a purer cigar. Additionally, a longer ash means more mass when it drops. This particular brand appears to drop its ash at the five sixty-fourths of an inch mark, measuring a fifth of an ounce. If that number remains consistent as I burn the remainder, then I can store this reliable information. Couple this with other information, such as whether the leaves were sun grown or shade grown, which can be deduced from the colouration of the wrapper, how the leaves themselves have been cured and fermented, then there is the country of origin, of course. I am sure you are aware, Watson, that tobacco leaves are grown in more than one part of the world?”

“Of course,” I lied.

“Significant quantities of the leaf are cultivated in Brazil, Cameroon, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, which as I say is where this particular cigar was imported from, Indonesia, Mexico, Nicaragua, the Philippines, Puerto Rico…” The exotic-sounding names all began to blur into one as he reeled them off without taking a breath. “The Canary Islands, even, surprisingly, Italy, and of course the plantations of the Eastern United States. The soil in each of these countries contains different nutrients and a scientific mind could therefore deduce the country of origin if it knew what to look for.”

Holmes paused his lecture and watched the greying ash finally tumble from cigar to dish. He scribbled a note in a leather-bound book using an elegant pen. He took one more look at the new heap of ash and continued writing.

“Truly, there is a wealth of knowledge to be gleaned from this humble pile of ash,” I said. Holmes appeared to miss the sarcasm in my tone.

He had the remarkable ability to force his mind to empty itself of useless information when he was done with it. That, perhaps, was every bit as impressive as his ability to cram it full of facts. Although there was no science to support his position, he remained convinced that the human brain could only retain so much knowledge, so he regularly created room by “forgetting” facts he considered unimportant. It certainly explained why he knew nothing about particular subjects and cared little for information that did not have a bearing on his detective work. In many ways, he was a simple soul: he just needed to know whether it was raining—which it was on that day—not understand how the clouds absorbed moisture and emitted it under the right and proper circumstances.

I would have preferred a warm summer day, allowing us to air out our rooms, but instead I would have to endure the experiment until it met its desired conclusion. I could only hope that the cigars were the only things that burned down to ash, not the four walls around us.

The ring of the bell at the street door broke the silence. Unsurprisingly, Holmes ignored it, still watching the glowing ember at one end of the cigar with interest. In contrast, I sprang to my feet, knowing who the caller was. Holmes had had few paying clients during the preceding weeks, while our bills remained alarmingly constant. He did not seek out custom, and it was not my place to find individuals with the type of intriguing problems that might interest my companion and help pay for our lodgings in the process. My own practice was frighteningly small and I would not be able to support us both for more than a week or two. It was ever a juggling act. Holmes had an unerring ability to be dismissive of problems I imagined he’d find fascinating, and became utterly absorbed by the minutiae I predicted he’d dismiss as pointless. He could be quite contrary. However, a chance encounter the previous day, while at my bank depositing what little my practice had produced in financial gain, had offered a chance of Holmes paying his way.

I opened the door to Mrs. Hudson’s knock. She handed me a card, which identified our caller as the man I had been expecting: G. Wilson Waugh, the manager of Shad Sanderson Bank in the city. I asked our landlady to show the gentleman up to our rooms.

The man who stood in our sitting room moments later was more youthful than most in his profession. His side whiskers were a dark brown, giving his face a dire look, and he looked uncomfortable in his damp, light wool suit. I offered our guest a seat on the couch. By this time, Holmes had completed his work with the burning cigar, had made his notes, and was in the process of sweeping the well-weighed remains into a basket. Taking his customary chair, he did not shake hands, but rather sat and looked intently at the visitor, his face a blank mask.

“Holmes, I met Mr. Waugh while I was at the bank. He was most considerate to help me with a matter and we fell into conversation. He mentioned a problem and I told him you might well be the fellow to come to his aid,” said I. Turning, I addressed the bank manager who shuffled his feet, a sign of nervousness if ever I saw one.

“Mr. Waugh, when we spoke at the bank, you mentioned there was a problem that mystified you,” I began. “Would you be so kind as to elaborate for Mr. Holmes?”

“Of course, Dr. Watson,” said he, nodding his head. “I appreciate you seeing me. The truth of the matter is, I remain stumped by the problem and could benefit from a wiser mind.”

“That would be mine,” Holmes said. “Tell me in as great detail as you can.”

“Our banking establishment has been finding various cashier accounts deficient at the end of each day. It is never the same cashier so we cannot begin to accuse any one person.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“Two weeks, sir,” Waugh said.

“And how much has gone missing each time?”

“By our accounts, we believe the sum total unaccounted for comes to three hundred pounds six pence.”

“Is it the same amount each time?” Holmes had barely moved, taking in everything about the speaker, who appeared not to notice, shifting his gaze from Holmes to me and back again.

“No two sums have matched.”

“And you say these are all different employees working the cashier windows?”

“Indeed they are; most having worked for us for a number of years. We trust each and every one of them.”

Holmes stopped questioning the man and appeared to consider the issue, his gaze taking in the banker, from his brightly polished shoes to his immaculately tailored suit, before focusing somewhere in the middle distance. I could almost hear the cogs whirring as his mind processed every last detail of Waugh’s appearance. I tried to apply my own mind in the same fashion, noting the cologne the man wore, deducing from the condition of his footwear that he’d visited the shoeshine boy on the corner—as I often did myself—before his arrival. Waugh fidgeted under the detective’s scrutiny and seemed increasingly uncomfortable. I, having had more than a few occasions to see his great mind at work, merely sat by and waited for his conclusions.

The dull early morning light filtered in through the thick curtains and the thin haze of cigar smoke, picking out that familiar aquiline profile, deep in thought.

“I daresay, you are a bold one,” Holmes finally said, a small smile cracking his severe face. Waugh looked positively stunned. “Have you noticed, Watson, that Mr. Waugh’s shoes are brand new? Italian made, judging by the stitching and suppleness of the leather, and only recently imported.” I said nothing, understanding immediately where Holmes was going. “Then, there is the pocket watch chain, new gold, and as of yet showing no signs of wear, suggesting it is a recent addition to his ensemble. One could assume that a bank manager is fastidious when it comes to personal appearance, after all, in order to be the part one must first appear the part, that is how one engenders trust and encourages fools to part with their money, wouldn’t you agree, Mr. Waugh?” The banker said nothing. “We must also consider the cut of his suit, which falls exquisitely on his slender frame, and is of the latest style from Savile Row. Such a suit would exceed the comfortable reach of a manager’s salary. I will concede that while bankers must present the most trustworthy of appearances, sometimes it is difficult to discount the obvious when it comes to financial impropriety. Additionally, Watson, I am sure you noted our guest’s topcoat when he arrived? Burberry’s, new gabardine if I am not mistaken. Also new.”

I shook my head, not having perceived any of these facts.

“If the amounts are random as are the days they go missing, I think we may safely rule out the possibility that one of the cashiers is being blackmailed. Equally, if as Mr. Waugh insists, the staff are trustworthy, then someone else must be at fault. Since customers cannot access the money drawers we may rule out the population of Greater London and instead conclude that a single individual is responsible, randomising the funds taken and the burgled drawers simply to cause confusion.”

“Sounds altogether reasonable,” I conceded.

“But, the bank officials are now growing alarmed and will shortly bring this matter to the police; after all, theft is the one thing in their business that cannot be countenanced. The public give their money to the bank for safekeeping. If the bank cannot be trusted to keep that money safe what is the point of using their services? The shadow of suspicion will cast its pall over the staff and our thief will be among them. That is why he is now worried as to how obvious his crime will be. Isn’t that so, Mr. Waugh?”

Waugh bolted upright, a look of terror on his pallid features as every ounce of blood drained from his face. It was immediately obvious he wanted to be anywhere else but 221B, under the scrutiny of Holmes’s all-seeing eye. I would have pitied the man, but for the fact that he was a crook.

“You, Mr. Waugh, are the thief. You have endeavoured to make it appear the work of others, but to a trained eye, you have been spending your ill-gotten gains on improving your appearance when not paying off the house. And I am not referring to your home, Mr. Waugh.”

Now Holmes had my attention. I swear Waugh thought the detective was consorting with the spirits; how else could he read his guilt so thoroughly? I wondered much the same myself, but knew the question had to have a far more mundane solution, like most spiritualists’ tricks.

“How in the world can you tell he owes a gambling debt?”

Holmes offered a wry smile. “You will note the way his hands jostle back and forth when he is nervous? It is a tell, as if his cupped palm still contains dice. In his mind’s eye, he is no doubt picturing the rolls that went awry, placing him in debt and precipitating the unfortunate sequence of events that have brought him to our door. No doubt Mr. Waugh here stole when he could no longer afford to cover his gambling debt on his own modest salary, thinking to replace the missing funds when his fortune improved. However, once he realised the checks and balances in place were insufficient to catch a thief in the act, he began stealing in earnest without fear of retribution or recrimination, and continued, exceeding his needs until ultimately guilt set in and made him dispose of it.”

“On expensive clothing,” I concluded.

“Precisely,” Holmes agreed.

“Why would he present you with this as a mystery if he is at fault?” I asked. Waugh remained frozen in his seat between us.

“Ah, my dear Watson, our young banker is merely testing his pretence at innocence and has found it to be useless. Without doubt, he is well aware that his crimes are going to be exposed and is already thinking through the implications. Isn’t that so, Mr. Waugh?”

“Are you going to turn me in?” Waugh asked. His voice had shifted its register, the panic clearly evident in his tone. I could see the instinct to run bright in his eyes.

“No. If I am any judge of human nature I should think you will turn yourself in this morning,” Holmes said without preamble. “You are clearly feeling the unbearable burden of guilt. Of course, if I do not read of your confession in tomorrow’s paper, I will inform the police myself. That should suffice.”

The air of agitation quickly left poor Waugh, who sank back into the couch, utterly defeated. “I am through.”

“Indeed you are. See him out, Watson.”

Holmes was no longer interested in the man. I steered the hapless Waugh back down the stairs and returned to our rooms to an unhappy Holmes.

“You made quick work of that, why do you look so glum?”

“You said it yourself, Watson, and more than once: we need a paying case or we will find ourselves in straits similar to the hapless Waugh. But not just any case: one that will not only pay its way, but one that will challenge my intellect.”

I offered a knowing smile. “Then you are in luck, my friend,” I replied. “Because I have scheduled a series of such visits today and I daresay at least one of these should prove a worthwhile challenge.”

Which, of course, was a bold statement. As the morning progressed Holmes grew less and less interested in the parade of clients and their problems, large or small. He was dismissive of their concerns, blunt in their dismissal, and repeated again and again that he was only interested in a true challenge, which I was rapidly coming to conclude was about as common as a unicorn in this city.

As I had made these appointments over the last several days, I will admit I had been filled with confidence, certain that we should have not one but several cases worthy of the great detective. The word you are looking for, dear reader, is hubris, but in my defence, of late I have increasingly spent time accompanying Holmes on these investigations, taking my notes and recreating the cases to the best of my recollection as yarns for publication. I believe I have become a better raconteur with each such effort, but every time Holmes reads the finished report and dismisses it as exaggeration bordering on outright falsehood. However, not once has he asked me to cease these efforts and the payment for each piece has been sufficient to compensate me for the time not spent practising medicine, keeping a roof over our heads. Indeed, our partnership has become so commonplace that Lestrade has come to expect us as a pair.

What I had not and could not have anticipated was that this July would prove to be one of the wettest in memory, which had turned my injured leg into a throbbing reminder of my time with the Berkshires. The discomfort proved a distraction as the afternoon wore on and potential clients came and went. I should not have been surprised when Holmes managed to solve each “mystery” with the same ease as he did our poor banker’s conundrum.

A Mrs. Mary Carrington arrived next, complaining of a missing pearl necklace. Holmes sent a withering look my way, obviously disappointed with the prosaic nature of the crime, but took a deep breath and turned his penetrating attention towards the woman. She was in her late fifties, crow’s feet prominent on her otherwise smooth face that suggested a life lived with lots of laughter and gave her an attractive air. As she sat in the guest chair, she fidgeted with her hands, constantly reaching up to her naked neck, no doubt missing the pearls.

“Mrs. Carrington,” Holmes said, not wasting time with anything as civil as introductions. “I am going to ask you a few questions. Please be completely honest with your answers.”

“Of course.”

“First, tell me about your finances,” Holmes said, bluntly.

She appeared shocked by such a bold approach, but didn’t shirk or seek to deflect the question as she might have done. “We are adequately provided for. My husband works for Shaw Brothers, a trading firm at the London Stock Exchange and has for the last two decades.”

“Yes, but that is not what I actually asked, dear lady. Have there been any irregularities in how your husband chooses to spend his money that you have noticed?”

“How so?”

“Are you, perhaps, paying bills later than you would have previously, or buying less expensive cuts of beef?”

“My husband pays our bills, of course, and we have a cook who goes to the market,” she said in a defensive tone.

“So, what you are really telling me is that you have no sense of your family’s fortunes?”

“I suppose… No, I do not,” she stammered, flustered. She couldn’t look him in the eye.

“Your perfume is, I believe, French, yes?”

“It is,” she replied then looked at me as if Holmes’s question marked some kind of madness she couldn’t follow. I inclined my head slightly, urging her to go with his line of enquiry.

“Your dress is also of French design, is it not?”

She paused to look down at her attire and nodded to confirm his observation.

“It is my belief your husband has suffered a reversal of fortune,” Holmes said. “He has favoured the French which has translated to the lifestyle you enjoy.”

“I’m sorry, but favoured how?” the woman asked, earning her a disapproving look from Holmes.

“He was investing in their financial instruments, I suspect. However, in March, a substantial loan was being proposed by the government and I believe he invested thinking the loan would be forthcoming. Instead, the loan was denied by the International Financial Society, the monies diverted to the United States of America to subsidise development of their railways, so your husband’s investments turned out poorly. He is now burdened with unexpected debts and I contend has hocked your necklace to cover the family’s obligations.”

Her jaw dropped in surprise, eyebrows shooting towards the ceiling. “How could he…?” her voice trailed off and I offered her my handkerchief to stem the tears rapidly welling in her eyes. It was not, all things considered, a happy end to her visit. After escorting her out, I returned to the sitting room and confronted my bored companion.

“How the devil can you not know the Earth orbits the sun, but recite by heart some obscure bit of financial business from four months ago?”

“Watson, my job is entirely dependent on what might drive others to commit criminal acts. Among those many causes will be various financial transactions including movements in the financial markets. I do not make a great study of the Stock Exchange, but I do follow it well enough to make such obvious deductions.”

“Obvious to you, but not to that poor woman,” I said. “How bad do you expect their difficulties to be?”

“If he is keeping the news from his wife and going so far as to pawn jewellery, I would suggest it is quite dire.”

Next, we entertained an elderly man who asked for Holmes’s help in finding his first love. He wrung his hands as his raspy voice pleaded that he had thought of her every day since they last saw one another when he was but sixteen.

“If you were so much in love, what separated you?” Holmes asked our guest.

“A difference in purpose, I suppose. I was determined to become successful in business, having been apprenticed to a man named Jorkin, and went to London to work. She wanted to raise a family and farm so remained out in the country. I suppose our love was not strong enough.”

“No, I daresay it could not have been, otherwise one of you would have joined the other. You are reaching your twilight years, sir, and I suspect you think of the young lady as a life that might have been. Believe me when I say seeking her out will not bring you happiness. It is best you keep her memory and not mar it with a current portrait.”

After the man left, I turned to Holmes and smiled. “That may have been the kindest thing I have ever seen you do.”

Holmes made a dismissive noise and lit his pipe, which had the virtue of having a far more pleasing aroma than the foul cigar.

A vicar came by seeking help with missing candlesticks but that too was easily solved, a solution so simple that I was fairly close to finding it myself before Holmes determined the conclusion.

With each dismissal my companion grew increasingly sour. I suggested we cancel the remaining appointments but he fortified himself with tea and insisted we not delay the inevitable.

“The sooner we dismiss the superfluous cases, the sooner a true challenge will present itself,” he declared. At least that was the plan. But as the morning turned to afternoon even I was beginning to despair. We worked through the potential clients without a single promising problem. By half past two, we had completed the interviews and I was at a loss. I suggested, as the rain had lightened by then, we take a stroll and clear our heads. I privately thought that it would also allow me to open a window and air out our rooms, which still stank of cigar smoke. We were gathering ourselves for a walk through the park when there was a ring at the bell.

“I thought you said we had exhausted your calendar?” Holmes said with some irritation. “I think I have indulged you enough for one day.”

“We have,” I replied. “I cannot say who this might be.”

Mrs. Hudson appeared at our door again, looking distinctly irritated; we had, after all, caused her to ascend the stairs many times already that day. The card she proffered to me was that of a Mrs. Hermione Frances Sara Wynter, with an address in Shoreditch, not the most salubrious of addresses. Holmes joined me in the doorway and took the card.

“She says she has no appointment but seems determined to see you,” said Mrs. Hudson to Holmes.

He began to shake his head dismissively when Mrs. Hudson continued boldly. “She’s an old woman, sir, and has likely put herself out a considerable bit to be here in this weather. I know you have had a busy day, but surely one more visitor could do you no harm?”

“Oh, very well,” Holmes said, spinning on his heel and resuming his place in the chair.

“Would you prepare some tea for her?” I said to Mrs. Hudson.

She smiled. “I already have the kettle on.” She withdrew to fetch our visitor. I resumed my own place, curious as to the nature of the visit, but could not resist pointing out to Holmes that our landlady appeared to have taken his measure as carefully as he measured others. He gave a derisive snort but said nothing further, which I chose to interpret as agreement.

Hermione Frances Sara Wynter was at least seventy, perhaps older, as wrinkles softened her features. She had her steel-grey hair tucked neatly under a dark bonnet and her dress was of a similarly dark hue, stern stuff highlighted by a white collar and several pieces of gold jewellery. Even I could tell she had or once had had considerable funds. She was barely five feet tall, the slight stoop of her shoulders robbing her of another two or three inches, and it was obvious that age was not treating her kindly.

“Mrs. Wynter, Sherlock Holmes at your service,” he said in tones kinder than any I had heard that day. He was making an effort, most likely for Mrs. Hudson’s benefit, but which I certainly appreciated.

“Thank you so much for seeing me without an appointment, Mr. Holmes.”

“I will admit I am seeking a case to occupy my mind so I find myself speaking with one and all,” Holmes said. “So tell me, how do you believe I can be of assistance?”

The elderly lady wrung her hands, worrying at a silk handkerchief and in the process presenting herself as the very picture of a woman in distress, though what was on her mind had to wait a few moments as Mrs. Hudson arrived and laid out afternoon tea. She poured first for Mrs. Wynter, and through some silent communication knew just how much milk and sugar to use. Holmes let the act play itself out without a word. He did not stir until Mrs. Hudson had closed the door behind her.

“How did you come to find me, Mrs. Wynter?”

“Giles DeVere, a business associate of my deceased husband, made mention of your considerable skills. I understand you helped him with a problem several years ago.”

I gave my companion a look with raised eyebrows, but he just nodded in agreement. The name meant nothing to me. I turned to our guest.

“Mr. DeVere is an industrialist up north,” she explained. “He and my dear Lyle were associates and we have maintained cordial contact since his passing.” I was intrigued as to how Holmes had helped DeVere, but now was not the time to press for details. “I am here about my son, Norbert,” she said before taking a sip of tea.

“Is he in some sort of trouble?” Holmes asked eagerly.

“He was due home in June,” said she, then trailed off.

“From where?”

“I’m sorry, I should explain. Norbert is with the Royal Navy. He is a lieutenant serving aboard HMS Dido.”

Being an avid follower of military matters in the press, I knew the Dido had seen action during the recent war against the Boers in South Africa, but seemed to recall reading the ship had returned some weeks back.

“And what is your concern?” Holmes prompted.

“I went to the docks to welcome my son home. I waited and I watched, but as our boys disembarked one by one, there was neither hide nor hair of him. Frantic, I asked his shipmates, but many did not know him and those who did said he was not aboard. I had a terrible time finding his superior officers and they refused to say what had become of him, no matter how much I begged. No one would give me any answers. I left with no idea if my boy was alive or dead.”

“Did you think to make inquiries at the Admiralty?” asked Holmes.

Mrs. Wynter nodded impatiently. “I have made several trips both to the Admiralty and the War Office—Dido sent a naval brigade to fight at Majuba you see, and I thought the army might have the information the navy could not provide. It was most vexing.”

It was clear to me that this woman had little understanding of how the different branches of Her Majesty’s armed forces worked. There was no need for her to bother the army, losing her precious time.

“People feigned ignorance, offered platitudes, wished me luck in finding him,” she went on without pause, “but few seemed genuinely interested in helping me locate Norbert.”

Holmes leaned closer, as did I, sensing there was more to this story.

“Finally, I found a secretary who agreed to look through the records after I was refused yet another meeting. He informed me that Norbert was listed on the Dido’s manifest as being Missing in Action.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said. In contrast my companion sat impassively offering nary a word of sympathy.

Mrs. Wynter shook her head. “There’s more. He said there was a footnote to the entry and from what he could discern, there was the suggestion that Norbert had deserted during battle.” Desertion was one of the most heinous crimes one could commit while in uniform. I could not hold back the wave of revulsion at the very notion, and she could not help but see it.

Holmes and I exchanged looks, mine of surprise, his of something else entirely, then returned our attention to Mrs. Wynter, who dabbed at her eyes with her handkerchief.

“Lyle and I had Norbert late in our married life and maybe we doted on him too much. However, Norbert may not be a war hero,” she looked me in the eye then, “but I did not raise my son to be a deserter.” I said nothing. “He may have died in battle, his body unrecovered, I can accept that. Too many of our boys are listed as Missing in Action. What I will not accept is his reputation… his memory… being tarnished in this way. I have exhausted all my efforts, Mr. Holmes. I am at the end of my strength. I need someone to take up the baton from me, and am hoping that someone might be you, a man known for his fierce dedication to the truth. I want to know what happened to my son. That is all. That should not be so much, should it?”

Holmes and I sat in silence for several moments as she continued to dab at her eyes. After nearly a full minute, he leaned forward and asked, “Please give me whatever details you have. Leave nothing out.”

The relief on Mrs. Wynter’s face was deeply affecting. She explained that her son was attached to the Dido, which was, in turn, posted to the West Africa Station from ’79. According to what the Admiralty revealed to her, young Norbert was part of the naval brigade that went ashore to join the Natal Field Force when the Boers rose up. It was therefore unlikely he would have been at Majuba Hill in February this year. Still, her boy did not return with the Dido in June.

“I have no idea if he even left Africa, or if something happened on board during the voyage home. Indeed, it is all a mystery to me,” Mrs. Wynter admitted. “The truth of the matter is that no one will tell an old woman what has become of her only son. I have made my appeals at Whitehall and the Admiralty, but as I told you, all I have learned is that he is classified as Missing in Action. He cannot be a deserter, Mr. Holmes. Norbert was faithful and loyal to the Crown. I know my boy; he would never abandon his post. In his letters, Norbert described his shipmates as if they were his brothers. Something else must have happened.”

“When did you last hear from him?” Holmes asked.

She reached into her small handbag and withdrew a well-worn document. Holmes’s long, tapered fingers snatched it from her and his eyes quickly scanned the contents. He then handed it casually to me, as if it were nothing of importance. The letter, dated 5th January, seemed innocuous—reports of shipboard high jinks and complaints about the food. It contained nothing about the war nor gave a clue as to Norbert Wynter’s disappearance that I could see.

Mrs. Wynter wrung her hands. “It is the not knowing that haunts me and keeps me awake at night. You can understand that, can’t you, Mr. Holmes? Norbert is no deserter. I know my own son. Someone is hiding the truth.” Her tone was filled with the anguish of a mother bereft and seemed to be begging Holmes to tell her she was right.

Holmes seemed far from convinced. His penetrating eyes remained fixed on hers, revealing nothing. I, however, will admit that I was moved by her appeal. Having been an Assistant Surgeon with the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers, I had seen the horror of war with my own eyes, albeit in Afghanistan and not Africa. I could imagine just how savagely the lack of knowledge gnawed away at the woman day and night. While my own mother was long gone, I could scarcely imagine what she might have felt had she heard of my injury. Weeks of not knowing how bad it was, if I would ever walk again. Just bringing it to mind caused me to lean forward and massage my knee. Holmes glanced in my direction, and I was sure he had ascertained my train of thought.

“Holmes, surely we can provide Mrs. Wynter with some assistance?”

“Some assistance, yes,” he began and in my eagerness to get him to commit, I uncharacteristically cut him off and turned toward Mrs. Wynter.

“Do you have a likeness of Norbert?”

“Yes, I do,” said she, and once more dipped into her bag, withdrawing a worn photograph. Norbert, tall, exceedingly thin, stood proudly in his naval uniform. His left hand clutched the sabre while his right thumb was tucked beneath the narrow black belt. To my eye, he appeared maybe twenty-five, certainly under thirty, with dark hair—brown rather than black I suspected—and a moustache that framed his upper lip. His eyes stared fixedly at the camera, filled with pride.

“It was taken when he was promoted to lieutenant,” she said with pride.

“A handsome lad,” I said politely. Holmes snatched the photograph from my fingers and examined it minutely for some time. He then returned it to Mrs. Wynter and rose to his feet.

“This appears to be a mere missing person case,” he said. She began to speak but he cut her off with a raised hand. “However, for the Royal Navy to hint at desertion speaks to something else, I think, something more than a mere missing seaman. For that reason and that alone I shall accept the case for my normal fee and shall commence work immediately.”

Mrs. Wynter rose, her face illuminated by her smile, making the wear of the years briefly fade away.

“I am ever so grateful, Mr. Holmes. If you are half as good as your reputation, I know that you shall find my son.”

“I shall find the truth about your son, Mrs. Wynter. Whether the actual man himself materialises along with it remains to be seen,” he corrected, hardly comfortingly, as he walked her to the door.