Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arachne Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

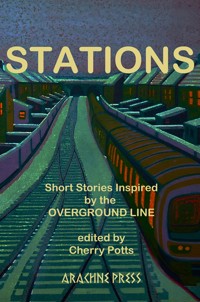

From tigers in a South London suburb to retired Victorian police inspectors investigating train based thefts, from collectors of poets at Shadwell to life-changing decisions in Canonbury, by way of an art installation that defies the boundaries of a gallery, Stations takes a sideways look through the windows of the Overground train, at life as it is, or might be, lived beside the rails: quirky, humorous and sometimes horrifying.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STATIONS

Short Stories Inspired

by the

OVERGROUND LINE

Edited by

Cherry Potts

CONTENTS

Overground - Introduction - Cherry Potts

Highbury - Inspector Bucket Takes the Train - Peter Cooper

Islington - Morning, Sunshine - Louise Swingler

Canonbury - All Change at Canonbury - Paula Read

Dalston Junction - Moving Mike - Wendy Gill

Haggerston - Platform Zero - Michael Trimmer

Hoxton - Bloody Marys and a Bowl of Pho - Caroline Hardman

Shoreditch High Street - The Horror, the Horror - Katy Darby

Whitechapel - Lenny Bolton Changes Trains - Rob Walton

Shadwell - Rich and Strange - Bartle Sawbridge

Wapping - The Beetle - Ellie Stewart

Rotherhithe - A Place of Departures - Cherry Potts

Canada Water - No Prob at Canada Water - Anna Fodorova

Surrey Quays - Three Things to do in Surrey Quays - Adrian Gantlope

New Cross - New Cross Nocturne - David Bausor

New Cross Gate - Yellow Tulips - Rob Walton

Brockley - How to Grow Old in Brockley - Rosalind Stopps

Honor Oak - Carrot Cake - Paula Read

Forest Hill - Mr Forest Hill Station - Peter Morgan

Sydenham - Actress - Andrew Blackman

Crystal Palace - She Didn’t Believe in Ghosts - Jacqueline Downs

Penge West - Penge Tigers - Adrian Gantlope

Anerley - Birdland - Joan Taylor-Rowan

Norwood Junction - Recipes for a Successful Working Life - Rosalind Stopps

West Croydon - All Roads Lead to West Croydon - Max Hawker

About the Authors

About Arachne Press

THE OVERGROUND

Introduction

Cherry Potts

The Overground runs at the bottom of my garden and my local station is a three minute walk away. Before there was the Overground, there was only Southern, but trains went to London Bridge, Victoria and Charing Cross. With the advent of the Overground, the Charing Cross trains were lost, and with them, the possibility of an easy last train home from many of my favourite central London venues. There was lamenting, there were protests, there was a coffin carried on the very last train. It was epic.

Then there was the disruption: the endless sleepless nights while the track was relaid and the station lengthened and the trees on either side of the cutting massacred. (More protests). There were the huffy, what use is it? conversations on rush-hour platforms, the disbelieving sneer when told the value of my home would increase, followed by the overcrowding, the noise… and then there was the eating of words.

Because the Overground is wonderful. It cut ten minutes off my journey to work, it halved the time to get to all sorts of North London places I had given up going to: the King’s Head, the Union Chapel and the Estorick Collection. It made getting to the Geffrye museum simple. It expanded my horizons. I ate my words.

Mentioning this in passing at a writing group meeting (spitting distance from an Overground station, average door to door journey eight minutes), as we settled for a twenty-minute writing exercise, Rosalind said: we should write about the Overground. So we did.

From that twenty minutes blossomed the idea for an entire book, with a story for every station on ‘our’ section of the line: Highbury & Islington to New Cross, Crystal Palace and West Croydon. Advertisements were placed, notice boards plastered, emails sent, and gradually over six months, the stories started coming in. The relevance of the trains themselves has faded into the storytelling a little, but the Overground remains the raison d’être of the book. So: thank you, Overground.

We didn’t know when we started this collection that the London Underground would be celebrating 150 years of existance just after publication, nor that the Overground would complete its circuit of London only a week after we published. Perhaps we should have known, but anyway, we were happy to have more reasons to celebrate the line.

HIGHBURY & ISLINGTON

Inspector Bucket Takes the Train

Peter Cooper

It was a rare thing for Inspector Bucket to take the train, old fashioned as he was about travel and much preferring the jogging of a hackney cab or omnibus to the snorting of a steam train. He complained that the railway only showed him the backsides of warehouses and factories and what he wanted, he said, was the courts, alleyways and streets of London, for it was there that the pickpockets and thieves of London Town would ply or plan their trade.

Indeed, despite the unpleasantly windy weather, we had travelled all the way from Vauxhall to Highbury & Islington Railway Station in a hackney cab rather than risk the train. The Inspector had been asked to attend a meeting there, he said. Yet here we were: him at his advanced age and me his long-term amanuensis, due, after all, to catch an evening train from North London Railway’s newest station.

It must be said that the station was a fine gothic building with an impressive forecourt, although its architecture was, frankly, more convivial than its railway staff! The clerk in the booking hall eyed us up as if he assumed we were only there with the intention of pinching the railway stock.

Mind you, I must confess I was embarrassed by Inspector Bucket talking loudly about an expensive gold necklace he said he had previously wrapped up in a handkerchief. He had been passing it from pocket to pocket rather obsessively. There was a niece of his in Kew who had been promised the jewellery as part of her wedding equipage, it seemed, but I saw no need for Inspector Bucket to announce this to the whole station. Also, now that we were exposed under the gas lights of the booking hall, I was alarmed at the state of his dress – particularly his greatcoat, which seemed very much a second best affair and rather stained at the pockets. Bucket had always been somewhat eccentric but now it seemed old age was making him careless.

Nevertheless, I was more surprised by the station itself than I was by the enigmatic Inspector Bucket. This was a busy and freshly appointed London station, yet it was strangely quiet and empty on what should have been a bustling Monday evening. I reasoned that it must have been the weather putting people off; though at the front of the station there was no pause in the movements of the cabs, the carts, the pedlars and the omnibuses. In the booking hall there was a small group of businessmen, a clergyman in a cassock and a rather handsome unaccompanied woman, but, apart from these, and a late-arriving gentleman who might have been an iron master from the manufactories, the booking office was doing slow business. A small number of other passengers were taking shelter in the first class waiting room and a few third class ones were leaning morosely against the glass, trying to find some shelter from the gale that was blowing up on the open platform. Several of the gas jets were already blown out and others were fitful. It was a relief to see the Cock Tavern, newly built into the station’s eastern wing, where a passenger with a thirst on him might wait in more convivial surroundings in front of a fire.

We sat in the corner out of habit but just as I was about to quiz Bucket about tonight’s exploits we were joined by an important looking gentleman.

‘Inspector Bucket?’ he said. ‘I’m Beddows.’ This was clearly the man whom Bucket had arranged to meet.

‘I’ve a nephew who works on the railways,’ Bucket said by way of an answer. ‘He’s always trying to get me to take a ride on a steam locomotive, but it don’t seem natural to me!’

I noticed the inky stains on Bucket’s fingers but I thought little of that at the time, other than observing to myself that he must have been writing through the long hours of the afternoon and that his elderly carelessness extended to the ink bottle.

‘Then, I’m very grateful to you for coming at all, Inspector,’ the gentleman was saying. ‘I wouldn’t have asked you but we’re desperate, you see. We’re losing revenue because of it all and the police have been unable to do anything about it!’

Bucket had retired from the Police Force nearly twenty years before, to open his own private detective bureau, but he was still always addressed as Inspector.

‘There are regular reports of robberies on the trains and we can’t seem to do anything to prevent them,’ Beddows continued wearily. ‘Even as passengers sit in their carriages they’re not safe! The result is that the station and the line are being by-passed by the better class of customer. Like you, Inspector, they’d sooner take a hackney cab, or omnibus,’ he sighed despairingly. ‘Most of the complaints from our passengers seem to mention the run from us to Willesden Junction. We’re the new station so I’ve got the rest of the railway board on my back to get the culprits caught – and I’m at my wit’s end, I don’t mind admitting it!’

‘And what precautions have been taken, Mr Beddows?’ asked Bucket.

‘Well, Inspector, the station masters have put warning notices on the platforms, of course, advising people to travel in groups if they can, and especially in the evenings,’ said Beddows. ‘Our ticket officers and guards keep a careful lookout for shifty looking characters and we’ve asked for policemen to be on patrol at all the station exits and entrances. We’ve even had our own men travelling in the carriages, ones sworn in as county constables I mean, but they can’t keep a watch on every carriage, can they?’

‘Would put off most thieves, I expect,’ said Bucket thoughtfully, ‘all those men in uniform. But I think you must have a local gang, and a brazen one, working your line – if the thefts are still occurring, that is?’

‘Well, there has been a let-up in the complaints, but only, I think, because we’ve fewer passengers travelling; but that’s not a solution the Board likes!’ Beddows sighed, taking out his watch at the sound of an approaching train. ‘That will be the seven o’clock coming in, Inspector. You’ll journey on the line for us, won’t you, and see what you think? I have a pass for you and your companion here.’

‘No need, Mr Beddows,’ smiled Bucket. ‘I thought it more appropriate to purchase tickets of our own. Now, if you will excuse me, we have a train to catch.’

There was a small group around the first class carriages, most of them warily sizing up their fellow passengers even as they hastened to get out of the gale. However, instead of the usual desire to find a carriage of their own, they seemed more intent in finding safety in numbers. Bucket was again noisily informing me that I shouldn’t concern myself and that the gold necklace was safe with him. He even patted gently at the very pocket. My concern at the signs of his growing confusion began to grow.

Our chosen carriage already had four people inside and the seats were narrow, but the blue buttoned cushions were comfortable enough. We were joined by a businessman, a young woman, and the clergyman. Only one of the gas jets was lit and this almost blew out before the door was closed by the manufacturing gentleman. When he sat down I felt that he seemed somewhat familiar but he paid no attention to me. Despite the cold outside, it seemed really quite warm in the carriage, squashed up with all these other people, and I noticed that even Bucket had unbuttoned his greatcoat.

Not a word was spoken by anyone other than the Inspector and, for a while, he seemed never to stop: ‘Won’t cousin Ada be pleased with the gold necklace?’ he was saying. ‘It’ll look fine on her, set off her other jewellery to perfection – though the gold necklace is far superior to anything cousin Ada has ever worn before, and she’s worn pieces envied at many London balls and by many a London jeweller, ain’t she?’

I felt embarrassed by his odd outpourings and looked out of the window at the dark shapes passing by. I am ashamed to say I was pretending that this old man in the later stages of his dotage had nothing to do with me.

No-one alighted until we reached Camden Town. A middle-aged lady carrying a small child was peering through the carriage windows as we pulled in. The clergyman took a good look at her, I noticed. When she finally settled on our carriage, the worthy manufacturing gentleman chose that moment, conveniently, to exit, or there would indeed have been a crush. She wore a heavy tweed cape, and the child was exceedingly well wrapped up in woollen blankets against the squall. She was a bustling, verbose personage who began addressing her fellow passengers from the first moment of her entry.

‘I feel so much safer travelling in a full carriage,’ she said. ‘You hear so many stories, don’t you? That poor gentleman who was murdered and left for dead on the tracks – do you remember reading about it? I know it was a few years ago, but, well, he made the mistake of sitting by himself, alone in a first class carriage, and nobody heard his screams, did they? Well, how could they, with all the noise of the engine and the train lines rattling? Hackney wasn’t it? Where it happened, I mean. Well, I’ve been nervous about travelling on the railway ever since, haven’t you?’

These observations seemed to give little comfort to her fellow passengers. The clergyman sitting next to me was looking nervous and the lady on the other side alarmed. The businessman clutched his case of papers more closely to his chest. I watched the gas jet flickering fitfully. The chattering lady continued to make similar comments almost all the way to the next station, only pausing when her little girl began moaning.

‘There, there,’ she said to her, and then looked up at us all. ‘My niece has been unwell, you see, and I must get her back to her dear mummy. Would you mind awfully,’ she said, addressing the clergyman who was sitting next to the window, ‘if we were to open the window just for a moment? I think the child is rather warm.’

The clergyman complied with her request without saying a word. The window was opened, a gale blew in and the remaining gas jet blew out. We were plunged into darkness and confusion. There was a scream and some gasps, and then a sudden jostling in the carriage. Somebody stood up, I imagined to extinguish the gas, or perhaps to attempt to re-light it, and I felt a hand brush past mine where I was sitting next to the silent Inspector Bucket. If the intention was to re-light the gas, it was evidently unsuccessful; however, after a moment, the window was shut again and to everyone’s relief we began to pull into the lit precincts of Chalk Farm Station. Everybody was back in their seats and glad to be in some light again, even smiling at each other in acknowledgement of our recent predicament and panic.

‘Well, this is my stop,’ said the lady, cradling the silent child in her arms.

‘This is the termination for us all, I believe!’ said Bucket suddenly, standing up. ‘I must ask you all to step off the train for a moment.’

Everyone was aghast, not least myself.

‘What’s the game?’ said the clergyman, whom I had not heard speak until that moment and who sounded less like a man of the cloth then any I had ever heard. ‘Who do you think you are?’

‘I’m no-one,’ said Bucket, ‘but this here gentleman is someone.’ The manufacturing gentleman who had left our carriage earlier had obviously just stepped out on to the platform at Camden and then stepped straight back into the next door carriage. He was now waiting, sentinel-like at our door, holding out his badge of office. He was a policeman! And now I recognised him as none other than our old friend Sergeant Meehan (now an inspector) who had been involved in the case of The Beast with us. As soon as a pair of burly officers had joined him from their position at the station’s exit, the passengers in the carriage had little choice but to step down.

‘What’s it all about Constable?’ the middle-aged lady was saying. ‘My poor daughter is ill you see. I must get her home.’

‘Oh, ‘daughter’ is it this time?’ said Bucket, raising his eyebrows. ‘You’ll be ashamed of yourself now, I expect, won’t you – using this ’ere small child for cover! Where have you picked the poor thing up from, eh? The streets? Hold her still, Inspector Meehan. Let’s see what we have hidden under these woollens, shall us?’

The small child whined but Bucket was gentle with her. ‘We won’t hurt you, my duck,’ he said, and withdrew an inkstained handkerchief wrapped around something shiny from amongst the folds of material. ‘Well, what have we here?’ he said, unfolding the handkerchief and holding its contents in his open, inky hand. ‘Look, an expensive gold necklace! Now, how did she come to have that tucked under her blanket, I wonder?’

In Bucket’s hand was not a necklace, of course, but a glass eye-dropper as used by doctors. A small amount of ink, or, as I discovered later, aniline dye, was still in the bottom of the unstoppered bottle.

‘I think we shall find a few ink stains on you too, madam,’ he said. ‘Shine your light here, Constable.’ And indeed there were stains, all down the woman’s dress and on the cape she was wrapped up in.

‘And your conscience will be stained too I expect, Vicar,’ said Bucket, staring at the clergyman. The light was duly shone and revealed a cassock stained with purple dye.

‘You picked my pocket when the light went out and you passed the parcel to this lady here, who then hid it under the child’s blanket,’ Bucket explained. ‘But I took the stopper out of the bottle just as you was dipping it out and the ink has shown who did it! Well,’ Bucket said, nodding at the constables to apply their handcuffs, ‘my friend at Highbury & Islington will be very pleased to have you two off his line while you walk up and down another one, doing shot drill at Tothill or Newgate. Take them away, Mr Meehan.’

‘Well,’ I said, when the figures had disappeared into the shadows, ‘You’ve surprised me again, Inspector Bucket. Is it back home on the next train then?’

‘No, my boy,’ he said, ‘call us a cab.’

HIGHBURY & ISLINGTON

Morning, Sunshine

Louise Swingler

‘Mornin’ darlin’!’ he says, ‘Ah, you’re an angel. You bring me a little bit of sunshine, you do.’

He takes the polystyrene cup from me, and places it carefully on the pavement. He’s sitting with his bottom half still tucked into his dirty red sleeping bag, and I can see the gloss of the earlier rain on the shiny fabric. I drop a pound in the old margarine carton on the grubby green blanket in front of him. The blanket flaps at the edges in the chilly March breeze.

‘Thanks darlin’ – you’re too good to me, you are.’

‘Ah, no,’ I say, feeling as I always do that his sweetness deserves more than the small round coin I give him whenever he’s here. But it adds up to about twenty-five pounds a month, what I spend on him. Money’s tight, with our impossible mortgage, but at least we’ve got the house that goes with an impossible mortgage, so I shut my ears to the cash-till in my brain. I don’t always feel like a sandwich at lunch anyway. I’m a bit early for work, so I light a fag, and offer him one.

‘I don’t mind if I do,’ he says, flashing a gappy but still charming smile from under his brown, unwashed fringe. He can only be about thirty, possibly younger. He has small sores on his pale skin, around his mouth and one on his neck; I can see it above the washed-out collar of the faded black rugby shirt he often wears. The sleeping bag isn’t one of those plump ones that taper towards your feet; this looks more like it cost a fiver at Argos – thin and flat, with a zip that’s buckled and broken halfway down. It must leave his flank exposed to the wind.

‘D’you like my display?’ he says, squinting up at me. Today he’s drawn some pictures, which are laid out across the blanket. One is a thousand smudges of green, blue and brown – a river coursing through green mountains. I wonder where he got the crayons; they look like quite good quality. On the blanket there’s also one of those red and yellow plastic windmills on a stick – you see them at the seaside in the top of sandcastles – but this one’s stuck in an old beer bottle, and now he picks it up to blow it. He has to blow hard, because one of the sails is a bit bent. He looks like a kid, his lips pursed up, a little spittle going with his breath into the windmill. I laugh, and he pauses, looking up with a half-smile.

‘It’s lovely,’ I say.

‘Ah, you’ve got to put on a display,’ he says, winking and pushing the fag I gave him behind his ear, ‘I like to make gorgeous ladies like you smile.’

And he does cheer me up; every day. More than anyone, actually. His morning, darlin’; or morning, sunshine, depending on how grey the day is, makes a difference.

Every morning, when I dash out of Highbury & Islington Station, I queue for a coffee from the silver trailer outside the station. Then, as I wait to cross Holloway Road at the pedestrian lights, I peep through the fast-flowing traffic to see if the giant scarlet caterpillar is lying alongside the wall of the bank opposite. If I can’t see it, I feel a little pang of disappointment as I hurry across the road. If he’s there, I give the coffee to him. If he’s not, I drink it when I get to the office.

I wave goodbye to him as I set off along the path across Highbury Fields, to the large mansion house where I work. Heights-Mitchell Developments, half way up on the opposite side, looking out in self-satisfied splendour over the fields.

‘Hey, I’m making another surprise for you,’ he calls, ‘make sure you come back later.’

About half-past five, we parade past him at speed on our way down to Cheriton’s. Peterson has booked their conference room for the monthly board meeting, and afterwards there’ll be wine and canapés in a sectioned-off part of the restaurant. Peterson strides along with Nigel, our Finance Director, and Fiona and I struggle to keep up, carrying plastic bags packed with agendas and papers. I can only grimace at sleeping-bagman, and I try to point at my watch to show I’ll be back later. He sends me a little salute, and rests back against the brick wall.

As we dash down Upper Street, I think of my girls waiting at Auntie Gee’s for Stu to collect them; it’s the second time this week he’s had to do it, and he was pissed off. Your job’s too much, he says. But it’s me that’s too much. The part of me that enjoys the way it grips me like a vice. I need, some figures for a meeting tomorrow, Jen. But it’s five-thirty already, Mr Peterson. I know, Jen; is there any way you could stay a bit late? Oh, okay, then, just this once. That’s how it goes, and I feel a little thrill when he leans on my desk, looking harassed and stressed out, and another when I give my agreement and he smiles with relief. It’s all a game; we both know I’d never refuse, but it’s a good game. He really rates my work; makes me know that I’m essential. Stu makes me feel crap at everything; a shit mother who’s never there; a wife who can’t keep house. I make a mental note to swipe some of the posh finger food to take home for the girls.

It’s an important meeting tonight. There are two representatives from the Residents Association in the area where the next Heights-Mitchell project is to be built. Peterson’s strategy is to make the deputation feel listened to, and to impress them with our corporate responsibility projects over a few glasses of free wine. But I’ve seen this pair at a consultation meeting, and although they look a bit grey and rubbed out at the edges, you can tell they’ve been lobbying for one thing or another ever since the 1960s. Nothing gets past them; they’re like crows at lambing time, picking your eyes out if you don’t keep moving. But that’s not completely fair; they do seem to act from a bedrock of integrity. Tested against Vietnam. Honed at Greenham. It’s Class A activism, not nimbyism, and I think Peterson’s too young to really get that. He’s only about twenty-eight, although he looks older since his promotion. He’s lost weight and the skin around his eye sockets has gone a bit pouchy, but his black hair is still glossy and thick.

They’re already there when we arrive. Grantly Witherthwaite and Pet Nanceworth. Grantly looks as mild and inoffensive as his name. He’s wearing a charcoal-coloured anorak which has one of those fastenings that demurely hides the buttons from view. He wears crisp old-man jeans, and has a well-clipped, speckled beard. Pet is tall and terribly thin, her face lined and tanned by a thousand fags, her tight, shoulder-length curls dyed a tinny red colour. She’s wearing black leggings and a purple tunic with a slash-neck which shows up her deeply-ridged clavicle bones and her scraggy throat. God, she looks tense; as if she could explode like a light bulb into silvery egg-shell fragments.

I see Pet’s thin lips compress even more tightly as her gaze settles on Tanya Selton. When Tanya came back from the last negotiation meeting with the Residents Association, she was swearing blue murder about these two. Peterson doesn’t usually allow representatives at Board Meetings, but he thinks they’ll be mollified if they’re allowed closer to the ‘seat of power’ as he calls it. Honestly! Even I have to admit he can sound a bit up himself sometimes. We’re a building development company, not the White House. But it’s just his way of talking himself up enough for the battle; he needs this to go well. It’s the first big project with him at the helm and he’s determined it’s going to be cutting edge, which, of course, is half the problem. Too modern for the residents.

Grantly sits up straight and coughs drily before setting out his points to the tableful of well-dressed board members. They’re all displaying the sort of concerned, thoughtful look that I’m sure must be taught on Day One of whatever training courses politicians attend. Grantly’s tone is slightly judicial and didactic. It reminds me of last night, when Stu and I had one of our meandering ‘discussions,’ where he tries to cajole me into to going part-time and I resist. He thinks he’d get on more quickly if I did; he’s aiming to be Area Manager within a year. He says his pay-rise would compensate for losing half my wages, and he recites an endless list of additional benefits. How can I explain my refusal when the main reason I want to hold onto this job is in case I can’t stand it anymore and need to leave him? So I just keep letting him needle me, and it’s exhausting. Now Peterson turns and winks at me as he prepares to speak, and I feel a gush of pleasure.

After Peterson has answered Grantly’s points, Pet takes over, her voice getting squeakier and her pomegranate-coloured curls shaking as she repeatedly stands up and is asked to sit again. She declares that Tanya has ignored, has concealed, evidence about the dangerous condition of the ground under the site. Tanya shakes her geometrically-bobbed head with a supercilious smile on her lips that is even annoying me; can’t she play the game and be pleasant? Peterson is rattled too, and he’s trying to get her eye, but Tanya just smiles down at her mauve nails. She manages to look so classy, despite the lacy black bra showing through her blouse, and those outrageous long talons. But then Pet leaps up again and strides towards Tanya, who momentarily cowers as she sees Pet’s wiry arm raised, the bony hand in a fist – God, No! Peterson is on his feet and around the table already, one of his arms held out stiffly across Tanya’s brocaded bosom, the other hand forming a fan to cover her face. Peterson braces himself as the angular bones of Pet’s bare forearm collide with his suited one; he has to use some strength to withhold the blow. Pet rubs her arm and cries out ‘But she’s a bloody liar’, and Peterson’s voice sounds almost liturgical as he booms ‘Sit down now, Mrs Nanceworth. Please go and sit down.’ And she does. No-one else has moved. No-one else needed to.

After the drinks session, Fiona and I stay to finish the half empty bottles. We are still high on the energy that near-violence spawns, and we have already relived the moment when Peterson’s arm shot out in front of Tanya about fifty times. It was a great moment – despite all his young-man’s brouhaha, I saw his basic goodness concentrated in his posture, in the undeniable nobility of his protective act. And it ended in victory for Heights-Mitchell. After Pet was asked to leave, it was obvious that Grantly was shocked and ashamed, so a compromise was quickly reached.

Later, Fiona and I stumble drunkenly back along Upper Street, and now we’re hooting with laughter as the unintentional comedy of the evening takes hold of us. The slightly righteous seriousness of Peterson’s rigid arm, stuck right out, and Pet bouncing off it like a cartoon character running into a wall. We have to keep stopping, we’re laughing so much.

‘Oh don’t get the poxy train,’ Fiona says, as I turn in behind the Post Office which conceals the entrance to Highbury & Islington Station, ’come and get a cab.’

It’s cold now, and I’d love to wander up to the yellow-fronted cab office with her. She would get out at Archway and give me a fiver, and then I’d take it the rest of the way over Highgate and down to Child’s Hill. But I’ve hardly any cash on me, and if I get any out now Stu will see my overspend when he checks the accounts. Bloody internet banking; it leaves nowhere to hide.

‘No, I’ll catch the ten past ten,’ I say.

As Fiona walks on up to the cab office, she turns and assumes Peterson’s now legendary stance, with her arm out and that daft look on her face, making me giggle as I run into the station.

It’s empty on the westbound platform. I look over at the other platform, where the North London Line trains used to stop, before they made this into a four-platform station. Sinful people like me used to congregate at the far end there, skulking against the wall to smoke a furtive fag. Can’t get away with that nowadays, either. There’s so little leeway left. Nine minutes to go. I shiver a little, and think of Stu getting angrier with every extra second that passes. I find tears climbing out of my eyes as I imagine what it must have felt like, being protected by Peterson’s arm, but I squash that thought. Self-pity only makes you weak, and anyway, Stu would never hit me. I’ll just have to out-bluff him over this part-time business. What was it my favourite vagrant said this morning? You’ve just got to put on a display for people.

Oh, shit! Sleeping-bag-man – I said I’d go back. He probably saw me walk past with Fiona, shrieking and larking about like he didn’t exist. Still eight minutes to go. If I miss this one the next one isn’t for twenty minutes, but I think I could make it, at least to say goodnight and slip him a fag.