Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

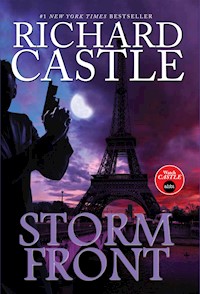

There's a Storm Front coming! Four years after he was presumed dead, Derrick Storm—the man who made Richard Castle a perennial bestseller—is back in this rip-roaring, full-length thriller. From Tokyo, to London, to Johannesburg, high-level bankers are being gruesomely tortured and murdered. The killer, caught in a fleeting glimpse on a surveillance camera, has been described as a psychopath with an eye patch. And that means Gregor Volkov, Derrick Storm's old nemesis, has returned. Desperate to figure out who Volkov is working for and why, the CIA calls on the one man who can match Volkov's strength and cunning—Derrick Storm. With the help of a beautiful and mysterious foreign agent—with whom Storm is becoming romantically and professionally entangled—he discovers that Volkov's treachery has embroiled a wealthy hedge-fund manager and a U.S. senator. In a heated race against time, Storm chases Volkov's shadow from Paris, to the lair of a computer genius in Iowa, to the streets of Manhattan, then through a bullet-riddled car chase on the New Jersey Turnpike. In the process, Storm uncovers a plot that could destroy the global economy— unleashing untold chaos—which only he can stop. Richard Cast is the author of numerous bestsellers, including Heat Wave, Naked Heat, Heat Rises, and the Derrick Storm eBook original trilogy. His first novel, In a Hail of Bullets, published while he was still in college, received the Nom DePlume Society's prestigious Tom Straw Award for Mystery Literature. Castle currently lives in Manhattan with his daughter and mother, both of whom infuse his life with humor and inspiration.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Heat Wave

Naked Heat

Heat Rises

Frozen Heat

A Brewing Storm (eBook)

A Raging Storm (eBook)

A Bloody Storm (eBook)

COMING SOON

Deadly Heat

RICHARD CASTLE

A Derrick Storm Thriller

TITAN BOOKS

FOR MY FATHER

Storm Front

Print edition ISBN: 9781781167892

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781167908

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

First edition May 2013

Castle © ABC Studios. All Rights Reserved.

This edition published by arrangement with Hyperion.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is purely coincidental.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

CHAPTER 1

VENICE, Italy

The gondolier could only be described as ruggedly handsome, with dark hair and eyes, a square jaw, and muscles toned from his daily exertions at the oar. He wore the costume the tourists expected of his profession: a tight-fitting shirt with red-and-white jailhouse striping, blousy black pants, and a festive red scarf tied off at a jaunty angle. He finished the outfit with a broad-rimmed sunhat, an accessory he kept fixed to his head even though it was nearly midnight. Appearances needed to be maintained.

With powerful, practiced movements, he propelled the boat under the Calle delle Ostreghe footbridge. When he felt they were sufficiently under way, he opened his mouth and let a booming, mournful baritone pour from his lungs.

“Arrivederci Roma,” he warbled. “Good-bye, au revoir, mentre . . .”

“No singing, please,” said the passenger, a pale, doughy man in a tweed jacket, with a voice that was vintage British Empire boarding school.

“But it’s-a part-a the service,” the gondolier replied, in heavily accented English. “It’s-a, how you say, romantic-a. Maybe we-a find-a you a nice-a girl, huh? Put you in a better mood-a?”

“No singing,” the Brit said.

“But I could lose-a my license,” the gondolier protested.

He rowed in silence for a moment, cocked his head directly toward the Brit, then resumed his crooning.

“Assshoooooole-omio,” he crooned. “Ooooo-sodomia . . .”

“I said no singing,” the Brit snapped. “My God, man, it’s like someone is squeezing a goat. Look, I’ll pay you double to stop.”

The gondolier mumbled a curse in Italian under his breath, but the singing ceased. The moon had been blotted by clouds, giving him little light by which to navigate. He focused on his task, pointing the boat’s high, gracefully curved prow toward the middle of the Grand Canal, then out into the open waters of the Laguna Veneta, a strange place for a gondola in the dark of night.

The currents were stronger here, and the flat-bottomed vessel was not well suited to the chop created by a stiffening breeze blowing in from the west. The gondolier frowned as the Campanile di San Marco’s tower grew faint in the distance behind them.

“Where are we-a going again?” he asked.

“Just keep rowing,” the Brit answered, his eyes surveying the darkness.

A few minutes later, three quick floodlight flashes split the night from several hundred yards away. They came from the bow of a small fishing boat that was approaching the gondola’s starboard side.

“There,” the Brit said, pointing to the right. “Go there.”

“Sî, signore,” the gondolier said, aiming the boat in the direction of the light.

Soon, they were alongside the fishing boat, a white fiberglass trawler. The gondolier took quick stock of its occupants. There were three, and they weren’t fishermen. One was stationed on the bow with an AK-47 anchored against his shoulder, the muzzle arching in a semicircle as he scanned the horizon. One manned the wheelhouse, with both hands firmly planted on the helm and a handgun holstered on his right hip. The third, an egg-bald albino, was in the stern, apparently unarmed, and focused entirely on the Brit.

This would be easy.

The fishing boat’s engine shifted into neutral and it slowly glided to a stop. Once the boats were stern to stern, a brief conversation between the Brit and the albino ensued. The gondolier waited patiently for the exchange, then it happened: a small, velvet bag passed from the albino to the Brit.

The gondolier made his move. The man with the AK-47 never saw the long oar leave the water and certainly didn’t realize it was tracking at high speed in his direction—at least not until the blade was three inches from his ear, at which point it was too late. He dropped to the bottom of the boat with a heavy thud.

One down.

The man at the helm reacted, but slowly. His first move was to leave the wheelhouse and inspect the noise. That was his mistake. He should have gone for his gun. By the time his error began to occur to him, the gondolier had already dropped his oar and leaped onto the fishing boat, and was approaching with hands raised. The gondolier had a full range of Far Eastern martial arts moves at his disposal but opted, instead, for a more Western tactic, delivering a left jab to the side of the man’s nose that stunned him, then a right uppercut to his jaw that severed any connection the helmsman had to reality.

Two down.

The albino was already reaching down to his ankle, toward a knife that was sheathed there. But he was also far too late and far too slow. The gondolier took one long stride, pivoted, and delivered a devastating back kick to the albino’s skull. His body immediately went slack.

The gondolier quickly secured all three men with plastic ties he had produced from his pants pocket. The Brit watched in dumbfounded terror. The gondolier didn’t even seem to be breathing heavily.

“All right, your turn,” he said to the Brit, pulling another restraint from his pocket, all traces of his Italian accent suddenly gone. He was . . . American?

“Who . . . who are you?” the Brit asked.

“That’s hardly your biggest problem at the moment,” the gondolier replied, preparing to reboard the gondola. “Being found guilty of treason is a much greater—”

“Stay back,” the Brit shouted, pulling a snub-nosed Derringer pistol from out of his tweed jacket.

The gondolier eyed the pistol, more annoyed than frightened. Intelligence had told him the Brit wouldn’t be armed—proving, once again, just how smart Intelligence really was.

Without hesitation, the gondolier performed an expert back dive, vaulting himself off the fishing trawler and into the choppy waters below. The Brit yanked the Derringer’s trigger, firing off a wild shot. The gondolier had moved too quickly. The Brit would have had a better chance hitting one of the innumerable seagulls in the faraway Piazza San Marco.

The Brit swiveled his head left, right, then left. He turned around, then back to the front. He kept expecting to see a head surface, and he fully intended to shoot a hole in it when it did. The Derringer was not the most accurate weapon, but the Brit was a deadly shot. Spies often are.

He waited. Ten seconds. Twenty seconds. Thirty seconds. A minute. Two minutes. The gondolier had disappeared, but how was that possible? Had the Brit’s bullet, in fact, struck its target? That must have been it. The man, whoever he was, was now at the bottom of the lagoon.

“Well, that’s that,” the Brit said, returning the Derringer to his jacket and gripping the sides of the boat so he could stand and survey his situation.

Then he felt the hand. It came out of nowhere, wet and cold, and clamped on his wrist. Then came the agony of that hand twisting his arm until it snapped at the elbow. He bellowed in pain, but his excruciation was short-lived: The gondolier vaulted himself onto the boat and delivered a descending blow to the side of the man’s head. The Brit’s body immediately lost whatever starch it once had, slumping, jelly-like, into the gondola’s seat.

“You should have let me sing,” the gondolier said to the Brit’s unconscious form. “I thought it sounded lovely.”

The gondolier snapped restraints on the Brit, found the velvet bag, and inspected its contents. A handful of diamonds, at least two million dollars’ worth, sparkled back at him.

“Daddy really ought to do a better job protecting the family jewels,” he said to the still-inert Brit.

The gondolier stood. He lifted his watch close to his face, pressed a button on the side, and spoke into it.

“Waste Management, this is Vito,” he said. “It’s time to pick up the trash.”

“Copy that, Vito,” said a voice that sprouted from the watch’s small speakers. “We have a garbage truck inbound. Are you sure you’ve finished your entire route?”

“Affirmative.” The gondolier surveyed the four incapacitated men before him. “Only found four cans. They’ve all been emptied.”

A new voice, one that sounded like it was mixed with several shovels of gravel, filled the watch’s speakers. “We knew we could count on you,” it said. “Good work, Derrick Storm.”

CHAPTER 2

ZURICH, Switzerland

The robber was in the kitchen. Wilhelm Sorenson was sure of it. With his heart racing, he closed in on the swinging door that led to the room and paused, listening for the smallest sound.

Yes, he heard it. There was a faint rattling from one of the copper pots that hung from the ceiling. It was the robber, for sure. The chase would be over soon. The robber would be captured and brought to justice. His version of justice.

Sorenson moved like an Arctic fox crossing tundra until his hand rested against the door. Another noise. This time, it was a giggle.

He did so love their version of cops and robbers.

“Oh Vögelein!” he called. Little Bird. His pet name for the robber.

She giggled again. He burst through the door, jowls flopping, breathing heavily from the exertion. This was the most exercise he ever got.

She was already gone. He felt moisture pooling on his brow, watched as the droplets rolled off his face and splattered on the floor. He had taken a triple dose of his erectile dysfunction medicine a half hour earlier, and the pills had dilated just about every blood vessel in his body. Now the blood was roaring through him, flushing his otherwise pale face to near purple and cranking his internal thermostat so the sweat was pouring from him as if he were an abattoir-bound hog.

It was a good thing none of the board members could see him right now, to say nothing of the press: Wilhelm Sorenson, one of the richest men in Switzerland and one of the most powerful bankers in the world, dressed only in socks, boxers, and suspenders, with a costume shop gendarme’s hat perched atop his head.

He had dispatched his wife to their chalet in the Loire Valley for a weekend of wine tasting with a group of lady friends, just what the old booze hound wanted. He had their mansion on the shores of Lake Greifen to himself.

Or, rather, to himself and Brigitte, the nineteen-year-old Swedish ingenue who had become the latest in a long line of Wilhelm’s barely legal obsessions.

Their little tête-à-têtes were not, under the strictest interpretation of law, illegal; just immoral, adulterous, and intrinsically revolting. Truly, there were few things more abhorrent to nature than the sight of Wilhelm, a married man pushing seventy, with a mass of lumpy, flaccid flesh overhanging his underwear, chasing after this sleek, blond, gorgeous young thing.

Nevertheless, this was their little game. She donned whatever absurdly priced lingerie he had bought for her most recently— this time, a four-hundred-dollar shred of feather-trimmed pink silk acquired on a trip to New York—and raced around the house. She drank directly from a 450-euro bottle of Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises the whole time. Five long pulls was enough to get her pretending to be drunk; ten would actually do the job, making her sure she could tolerate the feeling of him, grunting and sweating on top of her. Then she allowed herself to be caught, mostly so she could get it over with. It usually didn’t take him more than about five minutes.

“Oh, Schnucki!” she sang out. Her pet name for him. It roughly translated to “Cutey”—making it perhaps the least accurate nickname in the history of spoken language.

She was nowhere in the kitchen. He followed the mellifluous sound of her voice into the living room, the one with the soaring cathedral ceiling and the commanding view of the lake. Not that its placid waters had his attention at the moment.

“I’m coming to get you, Vögelein!” he said.

He stubbed his toe on the couch, swearing softly. He had not been drinking. He could barely perform sober. Drunk he would never be able to rise to the occasion, even with all those little blue pills he had consumed.

The giggling now seemed to be coming from the hallway that led to the foyer, so he followed the sound. Yes, this would be over soon. The foyer had a sitting room off it, but otherwise it was a dead end. She would soon be his.

Then he heard her scream.

Sorenson frowned. She wasn’t supposed to make it this easy. That wasn’t part of the game.

No matter. He would get what he wanted, then send her down into the city with his credit card for a night in the clubs. That way he could get some sleep.

“I’ve got you now, Vögelein,” he called out.

He rounded the corner into the darkened foyer and stopped. There were six heavily armed men dressed in black tactical gear. Their facial features were shrouded by night-vision goggles.

One of the men, the biggest of the bunch, had grabbed Brigitte by one of her blond pigtails and was pressing a knife against her throat. Her eyes had gone wide.

“What is this?” Sorenson demanded, in German.

The shortest man, a ball of muscle no more than five-foot-four, peeled off his goggles, revealing an eye patch and a face half-covered in the waxy, scarred skin left behind by severe burns. He brought a Ruger .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun level with Sorenson’s gut.

“Shut up,” said the man—Sorenson was already thinking of him as “Patch” in his mind—then pointed to the sitting room. “Go in there.”

Wilhelm Sorenson was the top currency trader at Nationale Banc Suisse, the largest bank in Switzerland, with assets of just over two trillion in Swiss francs. He moved untold fortunes in euro, dollars, yuan, and rand every day with the push of a button. His bonus alone last year was forty-five million francs, to say nothing of what he made on his private investments. No one ordered him around.

“This is . . . this is outrageous,” Sorenson said, switching to English himself. “Who are you?”

Patch turned to the guy holding Brigitte and nodded. The man jerked his knife hand, cutting a wide gash in the girl’s throat. Her scream sounded like it came from underwater. She fell to her knees. Blood poured from her severed carotid artery. Her hand went to her neck, but it was like trying to stop flood waters with a spaghetti strainer. The blood burst through her fingers.

“I’m no one to be disobeyed,” Patch said.

Sorenson watched in horror as the life bled from his plaything. He felt no concern for her, only for himself. The panic spread over him. He had given his security services the weekend off so he and Brigitte could have their tryst in private. He had a gun, an old Walther P38 his Nazi-sympathizer father had willed him, but that was locked upstairs in a safe. His phone was clearly not on his person, and in any event these guys did not look like they were going to let him make phone calls.

He was at their mercy.

“Please, let’s be reasonable here,” Sorenson said, trying to sound calm. “I’m a very wealthy man, I can . . .”

“Shut up,” Patch ordered, raising the .45 so it was in Sorenson’s face. “Move. In there.”

Sorenson felt a gun barrel in his back. One of the other men had circled around him and was using his weapon to shove him toward the sitting room. He slowly allowed himself to be herded there. He assured himself these men were not here to kill him. He needed to keep his wits about him. You don’t just kill a man like Wilhelm Sorenson. The repercussions would be too great. But this was clearly going to cost him a lot of money, to say nothing of a lot of embarrassment.

Sorenson took one last glance back at Brigitte, now facedown in a spreading pool of blood. How was he going to explain that to his wife? He had always been discreet with his little hobby, or at least discreet enough that he and the cow could pretend they had a normal marriage. Worse, Brigitte’s blood had seeped onto the antique Hereke they had found in Turkey. It was his wife’s favorite rug. Damn it. He was going to be in real trouble now.

When they reached the sitting room, Patch said, “There,” pointing to a high-backed Windsor chair that had been a gift from the Windsors themselves. Working without wasted movement, two men duct-taped Wilhelm to the chair, unspooling great lengths on his ankles, knees, hips, chest, and back. Only his arms were being left free.

“Whoever is paying you to do this, I can pay you more,” Sorenson said. “I promise you.”

“Shut up,” Patch said, backhanding him with casual viciousness.

“You don’t understand, I—”

“Do you want me to cut off your lips?” Patch asked. “I’ll happily do it if you keep talking.”

Sorenson clamped his mouth closed. They wanted to establish dominance over him first? Fine. He would let them do it. When the two men finished securing Sorenson to the chair, Patch unzipped a black duffel bag and pulled out an unusual-looking wooden block. It was the base for manacles of some sort, with oval slots for both wrists and adjustable clamps that allowed it to attach to a flat surface.

Patch looked around for a suitable table and found what he needed in the corner: a hand-carved ebony table from Senegal that had been inlaid with Moroccan tile. The thing weighed several hundred pounds. It had taken two men and a dolly to get it in place when it had been delivered three years earlier, and it had not been moved since then. Patch lifted it alone, barely straining himself in the process. He positioned it in front of Sorenson, then affixed the manacles.

Patch nodded, and the men who had been working the duct tape each grabbed one of Sorenson’s arms. Sorenson got the feeling they had done this before. Their every movement seemed practiced. They guided his arms into the manacles. Patch snapped the device down, then tightened it until Sorenson’s wrists were immobilized.

Patch pulled a pair of needle-nose pliers out of the bag and studied them for a moment. Then, without further comment, he systematically yanked every fingernail out of Sorenson’s right hand.

Sorenson screamed, cursed, pleaded, cajoled, threatened, whimpered, cried, and cursed some more. Patch was unmoved. He was focused on his task, no different than if he were yanking old nails out of a board. He paused just slightly between each digit to inspect the bloodied fingernail, then dropped it into a pouch on his belt. He loved fingernails. His collection numbered in the hundreds.

Sorenson’s thumb had been a little bit stubborn. Patch had to take it in three pieces. He frowned at the sloppiness of his workmanship. He would not save this one.

He nodded. His men removed Sorenson’s bloodied mess of a right hand from the manacle. Then Patch turned to the left.

“Now,” Patch said. “Tell me your pass code.”

Sorenson was on the brink of cardiac arrest. His heart was thundering at close to two hundred beats per minute. The pain had sent him into shock, so while he was sweating from every single pore, his body was ice cold.

“What . . . what pass code?” he panted.

Patch’s answer was to yank out the pinky nail on Sorenson’s left hand. The banker howled again. Patch calmly placed the nail in his pouch.

“Jesus, man, tell me which pass code,” he implored. “I’ll give it to you, I just need to know which one.”

“To the MonEx Four Thousand,” Patch said.

The MonEx 4000? What did they want with . . . It didn’t matter anymore. Only the pain did. And making it stop. Sorenson rattled off his pass code without hesitation. Patch looked over at a man whose long, flaming red hair protruded out from under his night goggles. The man pulled out a small handheld device and punched in the combination of letters and numbers Sorenson had provided. The man’s head bobbed down and up, just once.

Satisfied, Patch pulled the .45 out its holster and put two bullets in Sorenson’s forehead.

• • •

WHEN SORENSON’S BODY WAS DISCOVERED BY HIS GARDENER that next morning and reported to the local authorities, it was approximately 3 A.M. Eastern Standard Time.

It was around four-thirty when the computers at Interpol, the international policing agency, flagged the crime, noting its similarities to murders that had been committed in Japan and Germany in the five days preceding this one.

Within the half hour, Interpol agents confirmed the computer’s analysis and decided to implement their notification protocol. They began alerting their contacts across the globe, including American law enforcement.

The Americans dithered for an hour before deciding how to best handle it.

An hour later, at exactly 6:03 A.M., Jedediah Jones’s phone rang.

Officially, Jones worked for the CIA’s National Clandestine Service. His job title was head of internal division enforcement. Unofficially, his title’s acronym was suggestive of his true purpose. His missions, personnel, and budget did not, in any formal account of the CIA, exist.

The man calling said he was sorry for phoning him so early on a Saturday, but the truth was that he need not have bothered apologizing. Jones had been jogging at four, at work by five-thirty. He considered that his lazy Saturday schedule.

Jones took his briefing, thanked the man, and went to work, yanking the levers that only he knew how to pull.

It took about an hour for Jones to get his people on the ground in Switzerland, Japan, and Germany.

Within about two hours, he began receiving their preliminary reports.

It was when he learned that the killer in Switzerland had worn an eye patch that Jones realized that his next course was now decided. There was one man in his contact list whose training, intellect, and tenaciousness were a match for this particular killer.

He reached for his phone and called Derrick Storm.

CHAPTER 3

BACAU, Romania

It’s the eyes that get you. Derrick Storm knew this from experience.

You can tell yourself they’re just normal kids. You can tell yourself everything is going to work out fine for them. You can tell yourself that maybe they haven’t had it too bad.

But the eyes. Oh, the eyes. Big, dark, shiny. Full of hope and hurt. What stories they tell. What entreaties they make: Please, help me; please, take me home; please, please, give me a hug, just one little hug, and I’ll be yours forever.

Yeah, they get you. Every time. The eyes were why Storm kept returning to the Orphanage of the Holy Name, this small place of love and unexpected beauty in an otherwise drab, industrial city in northeast Romania. Once you looked into eyes like that, you had to keep coming back.

And so, having finished the job in Venice, Storm was making another one of his visits there. The Orphanage of the Holy Name was housed in an ancient abbey that had been spared bombing in World War II and was converted to its current purpose shortly thereafter. Storm had slipped inside its main wall, grabbed a rake, and was quietly gathering leaves from the courtyard when he saw a set of big, brown eyes staring curiously at him.

He turned to see a little girl, no more than five, clutching a tattered rag that may once have been a teddy bear, many years and many children ago. She was wearing clothing that was just this side of threadbare. She had brown hair and a serious face that was just a little too sad for any child that age.

“Hello, my name is Derrick,” he said in easy, flowing Romanian. “What’s your name?”

“Katya,” she replied. “Katya Beckescu.”

“I’m pleased to meet you.”

“I’m here because my mommy is dead,” Katya said, in the matter-of-fact manner in which children share all news, good or bad.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Storm replied. “Do you like it here?”

“It’s nice,” Katya said. “But sometimes I wish I had a real home.”

“We’ll have to see if we can do something about that,” Storm said, but he was interrupted.

A woman dressed in a nun’s habit, no more than four-foot-eleven and mostly gristle, approached with a stern face. “Off with you now, Katya,” she said in Romanian. “You still haven’t finished your chores, child.”

She directed her next set of orders at Storm.

“I’m sorry, little boy, but we’re not taking any more residents at the moment,” she said, switching to English that she spoke in a rich, Dublin brogue. “You’ll just have to run along now.”

“Hello, Sister Rose,” Storm said, dropping his rake and enveloping the nun in an embrace.

Sister Rose McAvoy smiled as she allowed herself to be semicrushed against Storm’s brick wall of a chest. She was pushing eighty, looked like she was sixty, moved like she was forty, and maintained the irrepressible spirit of the teenage girl she had been when she was first assigned to the orphanage many decades before, as a young novitiate. She always said she was Irish by birth, Romanian by necessity, and Catholic by the grace of God.

During her time at Holy Name, she had intrepidly guided the orphanage through the Soviet occupation and Ceauşescu, through the eighties’ austerity and the 1989 revolution, through the National Salvation Front and every government that followed, and lately, through the International Monetary Fund.

Improbably, she had kept the authorities appeased and the orphanage alive at every stage. If ever asked how she had done it, she would wink and say, “God listens to our prayers, you know.”

Storm wasn’t sure what to think about the force of His almighty hand, but he suspected the orphanage’s success had a lot more to do with Sister Rose’s abilities as an administrator, fundraiser, taskmaster, and loving mother figure to generations.

It certainly wasn’t because she had it easy. Sister Rose made it a point to take in the worst of the worst, the kids other orphanages wouldn’t touch, the ones who had almost no hope of being adopted. Many had been damaged by neglect in other orphanages. Many were handicapped, either mentally or physically. Some ended up staying well beyond the time at which they were supposed to age out, their eighteenth birthday, simply because they had nowhere else to go and Sister Rose never turned anyone out in the cold. They were all God’s children, so they all had a place at her table.

Storm had come across the orphanage years earlier, doing a job the gruesome details of which he made every effort to forget. Whenever he visited, he came with a suitcase or two full of large-denomination bills for Sister Rose.

Now they strolled, arm in arm, through the garden that Sister Rose had tended to as lovingly as she did her many children. Storm felt incredible peace here. The world made sense here. There was no ambiguity, no deceit, no need to parse motives and question whys and wherefores. There was just Sister Rose and her incredible goodness. And all those children with their eyes.

“Sister Rose,” Storm said with a wistful sigh, “when are you going to marry me?”

She patted his arm. “I keep telling you, laddy, I’m already hitched to Jesus Christ,” she said, then added with a wink: “But if he ever breaks it off with me, you’ll be my first call.”

“I eagerly await the day,” he said. Storm had proposed to her no less than twenty times through the years.

“Thank you for your donation,” she said, quietly. “You’re a gift from God, Derrick Storm. I don’t know what we’d do without you.”

“It’s the least I can do, especially for children like that,” he said, gesturing toward the little girl, who was now chasing a butterfly across the yard.

“Oh, that one,” Sister Rose said, sighing. “She’s a pistol, that one. Smart as a whip, but full of trouble. Just like you.”

Sister Rose patted his arm again, then the smile dropped from her face.

“What is it?” Storm asked.

“I just . . . I worry, Derrick. I’m not the spring chicken I used to be. I worry about what will happen when I’m no longer here.”

“Why? Where you going?” Storm asked, his eyebrow arched. “Don’t tell me: You’re finally taking me up on my offer to run away to Saint-Tropez with me. Don’t worry. You’ll love it there. Great topless beaches.”

“Derrick Storm!” she said, playfully slapping his shoulder. “You look like this big, strong man, but underneath it all you’re just a wee knave.”

Storm grinned. Sister Rose turned serious again: “The Lord has given me many blessed years on this mortal coil, but you know it won’t last forever. When he calls me, I have to go. He’s my boss, you know.”

“Yeah. Speaking of which, you ought to talk to him about his 401(k) plan. I was looking at your—”

Storm was interrupted by a ring from his satellite phone. He glared at it, considered ignoring it. It rang again. It was coming in from “RESTRICTED,” which meant he could guess its origin.

“Now, answer your phone, Derrick,” Sister Rose scolded. “I’ll not have you shirking your work on my watch.”

Storm let two more rings go by, and then when Sister Rose scowled at him, he tapped the answer button.

“Storm Investigations,” he said. “This is Derrick Storm, proprietor.”

“Yeah, I think my lover is cheating on me. Can you dive into the bushes outside a seedy motel, take some pictures?” came that familiar, gravelly voice he had last heard in Venice two days earlier.

Jedediah Jones was one of the few people left in Storm’s life who knew he had once been a down-on-his-luck private investigator, a decorated Marine Corps veteran turned ham-and-egg dick who actually did spend his share of time in just such bushes—if he was lucky enough to even have work. That was before a woman named Clara Strike had discovered Storm. They became partners. And lovers. And even though it ended badly, the lasting legacy of their relationship was that she had introduced him to the CIA and turned him over to Jones.

It was Jones who’d trained Storm, established him as a CIA contractor, and eventually turned him into what he was today: one of the CIA’s go-to fixers, an outsider who could do what needed to be done without some of the legal encumbrances that sometimes weighed down the agency’s agents. Jones’s career had thrived with many of Storm’s successes.

“I’m sorry, sir,” Storm said, playing along. “I know you’re hurt by what your lover is doing. But I don’t take pictures of goats.”

“Very funny, Storm,” Jones said. “But joke time is over. I’ve got something with your name on it.”

“Forget it. I told you after Venice that I was taking a long vacation. And I mean to take it. Sister Rose and I are going to Saint-Tropez.”

Storm winked at the nun.

“Save it. This is bigger than your vacation.”

“My life was so much better when I was dead,” Storm said wistfully. He was only half-kidding. For four years, Storm had been considered killed in action. There were even witnesses who swore they saw him die. They never knew that the big, messy exit wound that had appeared in the back of his head was really just high-tech CIA fakery, or that the entire legend of Storm’s death had been orchestrated—then perpetuated—by Jones, who had his own devious reasons for needing the world to think Storm was gone. Storm had spent those four years fishing in Montana, snorkeling in the Caymans, hiking in the Appalachians, donning disguises so he could join his father at Orioles games, and generally having a grand time of things.

“Yeah, well, you had your fun,” Jones said. “Your country needs you, Storm.”

“And why is that?”

“Because a high-profile Swiss banker was killed in Zurich yesterday,” Jones said, then hit Storm with the hammer: “There are pictures of the killer on their way to us. He’s been described as having an eye patch. And the banker was missing six fingernails.”

Storm reflexively stiffened. That killer—with that M.O.— could only mean one thing: Gregor Volkov was back.

“But he’s dead,” Storm growled.

“Yeah, well, so were you.”

“Who is he working for this time?”

“We’re not a hundred percent sure,” Jones said. “But my people have picked up some talk on the street that a Chinese agent may be involved.”

“Okay. I’ll take my briefing now if you’re ready.”

“No, not over the phone,” Jones said. “We need you to come back to the cubby for that.”

The cubby was Jones’s tongue-in-cheek name for the small fiefdom he had carved out of the National Clandestine Service.

“I’ll be on the next plane,” Storm said.

“Great. I’ll have a car meet you at the airport. Just let me know what flight you’ll be on.”

“No way,” Storm said. “You know that’s not the way I operate.”

Storm could practically hear Jones rubbing his buzz-cut head. “I wish you could be a little more transparent with me, Storm.”

“Forget it,” Storm said, then repeated the mantra he had delivered many times before: “Transparency gets you killed.”

CHAPTER 4

NEW YORK, New York

Soaring high above lower Manhattan, Marlowe Tower was a ninety-two-story monument to American economic might, a glistening glass menagerie that housed some of the country’s fiercest financial animals. In New York’s hypercompetitive commercial real estate market, merely the name—Marlowe Tower—had come to represent status, to the point where neighboring properties bolstered their reputations by describing themselves as “Near Marlowe.”

Marlowe Tower was a place where wealthy capitalists went to grow their already large stake in the world. After parking their expensive imported cars at nearby garages, they entered at street level through the air lock created by the polished brass revolving doors, wearing their hand-crafted leather shoes and custom-tailored silk suits, each determined to make his fortune, whether it was his first, his second, or some subsequent iteration thereof.

G. Whitely Cracker V joined them in their battle each day. But to say he was merely one of them did not do him justice. The fact was, he was the best of them. His Maserati (or Lexus, or Jaguar, or whatever he chose to drive that day) was just a little faster. His shoes were just a little finer. His suits fit just a little better.

And his executive suite on the eighty-seventh floor made him the envy of all who entered. It was six thousand square feet—an absurd bounty in a building where office space went for $125 a square foot—and it included such necessities as a coffee bar, a workout area, and a multimedia center, along with luxuries like a full-time massage therapist, a vintage video game arcade, and a feng shui-themed “decompression center” with a floor-to-ceiling waterfall.

As the CEO and chief proprietor of Prime Resource Investment Group LLC, Whitely Cracker had won this palace of prestige the new old-fashioned way. He’d earned it—by taking an already huge pile of family money, then leveraging it to make even more.

Whitely Cracker was the scion of one of New York’s wealthiest families—the Westchester Crackers, not the Suffolk Crackers— and could trace the origin of his name to 1857, with the birth of his great-great-grandfather.

The first in the line had actually gone by his given name, Graham. This, naturally, was before the National Biscuit Company came on the scene and popularized the slightly sweetened rectangular whole wheat food product. Graham W. Cracker had been a visionary who had made a fortune by luring Chinese workers across the Pacific to build railroads for substandard wages. That Graham Cracker gave his son, Graham W. Cracker Jr., seed money that he used to create a textiles conglomerate.

This set the pattern honored by all the Graham Crackers who followed: Each made his riches in his own area, then helped set up his son to make money in an industry befitting his generation.

Graham W. Cracker III struck it rich with oil refineries. G. W. Cracker IV—the popularity of the aforementioned Nabisco product had necessitated the use of initials—had been in plastics. And in keeping with the modern times, G. Whitely Cracker V, who used his middle name so no one confused him with his father, had become a hedge fund manager.

Yet while all this wealth and success might make them seem detestable, the fact was people couldn’t help but like a guy named Graham Cracker. And G. Whitely Cracker was no exception. At forty, he was still trim and boyishly handsome, with but a few wisps of gray hair beginning to blend in with his ash-blond coiffure. He smiled easily, laughed appropriately at every joke, and shook hands like he meant it.

He coupled this effortless charm with a gift for remembering names and a warmth in his relations, whether personal or professional. He was self-deprecating, openly admitting that his wife, Melissa—who was adored in social circles—was much smarter than him. And in a world full of philanderers, he was unerringly faithful to her.

He was also endlessly generous to his employees, whom he treated like family. He was a friend to nearly every major charity in New York, lavishing each with a six-figure check annually and seven-figure gifts when any of them found themselves in a pinch. And if ever he was panhandled by an indigent, he kept a ready supply of sandwich shop coupons—nonrefundable and nontransferrable, so they couldn’t swap the handout for booze.

It was this last trait that led to one glossy magazine deeming him the “Nicest Guy in New York.”

Everyone, it seemed, liked Whitely Cracker.

Which made it all the more confounding that he was being stalked by a trained killer.

• • •

WHITELY CRACKER WAS, NATURALLY, UNAWARE OF THIS AS HE drove in from Chappaqua. He had kissed Melissa at 5:25 A.M. that Monday, put on his favorite driving cap and driving gloves, the ones that made him feel like a badass, climbed into his vintage V12 Jaguar XJS, because he was in a Jaguar kind of mood that day, and made the drive to Marlowe Tower, tailed several car-lengths back by an unassuming white panel van.

That Whitely was a creature of habit made him surpassingly easy to stalk. He liked to be at his office by 6:30 A.M. at the latest, to get a good head start on his day. This was not unusual among the kind of people who populated Marlowe Tower, some of whom passive-aggressively competed with one another to see who could be the first to push through the brass doors each day. The current winner clocked in shortly after four each morning. Whitely Cracker had no patience for such foolishness. What was the point of being absurdly wealthy if you couldn’t set your own schedule?

By 7 A.M., he had dispatched a few small items that had built up overnight from markets in Asia and Europe, beaten back his accountant, the always-nervous Theodore Sniff, and retreated to his in-office arcade. Every super-rich guy needed some eccentricities, and classic video games were Whitely’s. They soothed him, he said, but also focused his brain. He claimed to have invented one of his most lucrative derivatives while battering Don Flamenco in Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out.

On this morning, he made sure Ms. Pac-Man was well fed. He burnished Zelda’s legend for a little while. Then he switched to Pitfall!, where he amassed a small pretend fortune by swinging on ropes and avoiding ravenous alligators —oblivious that he had a real predator’s eyes on him, albeit electronically, the whole time.

When he had finally satisfied his pixel-based urges, it was nine-fifteen, which meant it was time to turn his attention to his actual fortune. He left the arcade, smiling and waving at the employees he passed on the way, and returned to his office, where he settled in front of his MonEx 4000 terminal. He entered his password, the one that only he knew, and it came to life.

The MonEx 4000 had, in the last few years, become the preferred platform of the serious international trader, replacing a variety of lesser competitors. Faster and more versatile than its rivals, it provided access to all major markets, currencies, and commodities, seamlessly integrating them into one interface. Its operations were baffling to anyone unfamiliar with the bizarre language of the marketplace—its screen would appear to be something like hieroglyphics to a layman—but a seasoned trader could work it like a maestro.

Whitely Cracker made it sing better than most. He was legendary among fellow traders for his ability to keep up with a myriad of complex deals simultaneously. In the worldwide community of MonEx 4000 users, many of whom only knew each other virtually, Whitely’s virtuosity had earned him the nickname “the great white shark”—because he was always moving and always hungry.

This day was no different. Within a half hour of the opening of North American markets, he had already made twelve million dollars’ worth of transactions, and he was just getting warmed up. He had just pulled the trigger on a 1.1-million-dollar purchase of cattle futures—he would sell them long before they matured four months from now, because Lord knows there wasn’t space in the decompression center for that many cows—when the MonEx 4000’s instant messaging function flashed on the top of his screen.

It was from a trader in Berlin to whom Whitely had just made an offer.

Selling short again, White?

Whitely’s handsome face assumed a slight grin. His fingers flew.

Just hedging some bets elsewhere. Looking to shore up some significant gains. You know how it is.

The top of the screen stayed static for a moment, then a new message appeared.

Ah, the great white strikes again.

Whitely studied this for a moment, weighed the benefits of prodding the guy a little bit, and decided there could be no harm. He was offering the Berliner what would appear to be a solid deal. The guy would be a fool not to take it.

Don't worry. You're not my tuna today. Just a small mackerel. Maybe even a minnow.

Whitely enjoyed this, the jocularity of bantering traders. He liked the money, too. But the real benefit was, simply, the deal itself. He was an unabashed deal junkie. Buy low, sell high. Unearth an undervalued asset, snap it up. Discover an overvalued asset, sell it short. Big margins. Small margins. Didn’t matter. The deal was his drug. Whether he made millions, thousands, or mere hundreds was immaterial. As long as it was a win. The high was incomparable. When he was trading, he was even more engrossed than he was when he played his video games. The hours just slipped by. The outside world barely mattered when he was trading.

He certainly didn’t notice that his every move—and every trade—was being captured by three tiny cameras that had been hidden behind his desk: one in the bookcase, one in a picture frame, one in the liquor cabinet.

Each had a perfect view of every trade he offered and accepted. Each relayed its crisp, high-definition video feed to an office on the eighty-third floor.

On the other side of his desk, and littered in numerous spots throughout those six thousand square feet, there were more cameras and bugs. It helped that Whitely preferred such lavish furnishings: It made for more hiding places. His home in Chappaqua, his various cars, anywhere he regularly went—even his health club — were festooned with them. There was nothing he did, no conversation he had, that wasn’t being monitored by a person well trained in the ways of killing.

Whitely was oblivious to it all, just as he was oblivious for the first three minutes Theodore Sniff spent lurking in his doorway midway through the morning. Sniff had been Prime Resource Investment Group’s accountant since its inception. He did not have his boss’s charm, and certainly lacked his good looks: Sniff was short, fat, and balding, the Holy Trinity of datelessness. His clothes, which seemed to wrinkle faster than ought to have been scientifically possible, never fit right. By the end of his long days at the office, his body odor tended to overpower whatever deodorant he chose. Even with a salary that should have made him plenty attractive to the opposite sex—or at least a certain opportunistic subset of it—Sniff hadn’t been laid in years.

His lone gift was for accounting. And there, he was genius, capable of keeping a veritable Domesday Book’s worth of accounts and ledgers at his command. Whitely leaned heavily on this ability because, in truth, he couldn’t really be bothered to oversee these things himself. Whitely took pride in his instincts as a trader, instincts that had built an empire. He could feel changes in the marketplace coming the way the Native Americans of yore could feel the ground trembling from buffalo. But keeping up with the books? Boring. Melissa told him he should make more of an effort. He told her that’s what Sniff was for.

Cracker was so loath to pay attention to the bottom line, he even tended to overlook when Sniff was in the room. For Whitely, a man ordinarily so attuned to his staff, ignoring Sniff was like a congenital condition. There was seemingly nothing he could do to stop it. The accountant was entering his fourth minute of standing in the doorway before he finally coughed softly into his hand. Whitely did not look up from his screen. Sniff rattled the change in his pocket. Nothing. Sniff cleared his throat, this time louder. Still nothing. Finally, he spoke.

“Sorry to interrupt,” Sniff said. “But it’s important.”

“Not now, Teddy,” Whitely said. Whitely always called him Teddy. Whitely used the name affectionately; he thought it brought the men closer. Sniff never had the courage to tell his boss he abhorred it.

“Sir, I . . .”

“Teddy,” Whitely said sharply, without taking his eyes off his screen. “I’m trading.”

Sniff turned his back and slinked off.

The camera in the far corner caught his dejected look as he departed.

CHAPTER 5

LANGLEY, Virginia

Derrick Storm was a Ford man.

Maybe that didn’t seem like a very sexy choice for a secret operative. Maybe, in a nod to the great James Bond, he should have gone with an Aston Martin, or a Lamborghini, or, heck, even just a Beemer.

But, no. Derrick Storm liked his Fords. He was an American spy, after all. And an American spy ought to have an American ride. Besides, he liked how they handled. He liked the familiarity of the instrument panel. He liked knowing that he had good old Michigan-made muscle at his command. When he was a teenager, his first car had been a non-operating ’87 Thunderbird he bought off a buddy for five hundred dollars of lawn-mowing money and nursed back to glorious health. He drove the car all through high school and college. That had been enough to hook him. He had driven Fords ever since.

And, in truth, they were a much more practical choice for a man of his profession. Tool around in a Bentley just once and everyone notices you. Drive the exact same route every day in a Ford Focus and you might as well be invisible.

He kept Fords stashed near airports in many of his favorite cities. In New York, for example, he had recently purchased a new Mustang, a Shelby GT500 with a supercharged aluminum-block V8—a spirited revival of an American classic. In Miami, he kicked it old school, going with a ’66 T-Bird convertible, with the 390-cubic-inch, 315-horsepower V8. In Denver, he had an Explorer Sport, good for climbing mountain passes on the way to ski slopes.

In Washington, he kept a blue Ford Taurus. It was a staid choice for a town where ostentatious displays of wealth had been historically frowned on. But this wasn’t just any Ford Taurus: It was the SHO model, the one with the 3.5-liter, 365-horsepower twin-turbo EcoBoost engine, the one capable of throwing 350 pounds of torque down on the pavement. Much like Storm himself, it was a car that looked ordinary on the outside but had a lot going on under the hood.

It also handled bends well, which made it nicely suited to the George Washington Memorial Parkway, which was where Storm found himself just after noontime on Monday. It was a route Storm traveled often, not only because its tight curves made it one of the more enjoyable roads to drive in the D.C. area, but because it led to CIA headquarters.

He slowed as he passed the oft-mocked sign that read “George Bush Center for Intelligence Next Right” and took the winding exit ramp. He passed through Security, parked, then stopped at Kryptos, the famed copperplate sculpture containing 1,735 seemingly random letters, representing a code that has never fully been broken.

“Some other time,” Storm said, moving on to the CIA’s main entryway, an airy, arched, glass structure.

There, he was met by Agent Kevin Bryan, one of Jedediah Jones’s two trusted lieutenants.

“The hood?” Storm said by way of greeting.

“The hood,” Bryan replied, handing him a piece of black cloth.

“Jones better have some seriously cool toys waiting for me.”

“Toys?”

“Gadgets. Devices. Exploding toothpaste. Pens that are actually tiny rockets. Something. I know you guys have been holding out on me.”

“We’ll see what we can do. Meantime, the hood.”

The hood. Always, they made him wear the hood. Even with all his security clearances, even with background check after background check, even with all the times he had proven his loyalty, he still had to wear the hood when he was being escorted to Jedediah Jones’s lair, aka the cubby.

He understood. At the CIA, there’s classified, there’s highly classified, there’s double-secret we’d-tell-you-but-we’d-have-to-kill-you classified.

Then there’s the unit Jedediah Jones created.

It was so classified, it didn’t even have a name. It was a kind of agency within the agency, one whose primary mission was to remain as invisible as possible. Its existence was not explicitly stated in any CIA materials. The allocations that funded it could not be found in any CIA budget. Its employees did not have files in the personnel office, nor could they be found on the office phone tree, nor did they appear on e-mail listservs, nor were their paychecks drawn from normal CIA accounts. Its organization chart was a running gag—Jones handed his people a takeoff of a famous Escher print, one where there was no beginning and no end. The names on the chart were all cartoon characters.

The architect of this domain—and the master of it—was Jones. He had created this shadowy cadre many years before and, with a seemingly innate understanding of how to manipulate the sometimes-stubborn controls of a federal bureaucracy, had since built it into the elite unit it was today. He did it with a mix of obeisance and threats. Everyone in the high reaches of the CIA seemed to fall into two groups: either they owed Jones a favor, or he had dirt on them.

With the hood on, the trip to the cubby always felt a little disorienting. Storm was led down a hallway to an elevator, which felt like it first went up, then down, then over, then up again, then down some more. It was like being on an elevator in Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, only it didn’t smell as good.

By the time the ride was over, Storm was left with the feeling he was underground somewhere, but it was impossible to know for sure. The cubby had no windows, just an array of computers, wall-mounted monitors, and communications devices. They were run by a group of men and women known collectively as “the nerds,” a term that was spoken with fondness and great respect for their abilities. The nerds had been pulled from a broad spectrum of public and private industry to form a cyber-spying unit that was second to none.

From the comfort of their high-backed chairs, the nerds could read a newspaper over the shoulder of a terrorist in Kandahar, monitor an insurgent’s attempts to make a bomb in Jakarta, or follow a suspected double agent through the streets of Berlin. They also had access to virtually every database, public or private, government or civilian, that anyone had ever thought to compile. If it was on a computer that ever connected to the Internet, the nerds could eventually put it at Jones’s fingertips. They just had to be asked.

As usual, Bryan removed Storm’s hood when the elevator doors opened. Storm was greeted by a man who appeared to be about sixty. He wore an off-the-rack blue suit that draped nicely over his fit body. He was average height, with a shaved head, pale blue eyes and, at least for the moment, a wry smile.

“Hello, Storm,” he said in his trademark sandpaper voice.

“Jones.”

“It’s good to see you, son.”

“Wish the circumstances were better.”

“You look great.”

“You look like you need a tan.”

“Sunlight’s not in my budget,” Jones said.

“You bring me here to small-talk?”

“Not really.”

“Well, come on then,” Storm said. “Let’s get to it.”

• • •

STORM FOLLOWED JONES INTO A DARK CONFERENCE ROOM. IN ADDITION to Agent Bryan, they were joined by Agent Javier Rodriguez, Jones’s other top lieutenant. Jones clapped twice and the room was instantly illuminated.

“Really, Jones?” Storm said, raising an eyebrow. “The Clapper?”

Jones offered no reply.

“The most futuristic technology the world has never seen, spy satellites that alert you when a world leader farts, databases that could produce Genghis Khan’s first grade report card . . . And you turn the lights on with the Clapper?”

“The damn automatic sensor kept failing, and there’s only one electrician in the whole CIA with a high enough security clearance to come here and fix it,” Jones explained. “Plus, we like the kitsch value. Sit down.”

Storm took a spot midway down the length of a cherry-top table with enough shine to be used as a shaving mirror. A motor whirred, and a small projector emerged from the middle of the table. Jones waited until the motor ceased, then clicked a button on a remote control, and a 3-D holographic image of an unremarkable middle-aged white man appeared, almost as if floating on the table. Without preamble, Storm’s briefing had begun.

“Dieter Kornblum,” Jones said. “Senior executive vice president for BonnBank, the largest bank in Germany. Forty-six. Married. Two kids. Net worth approximately eighty million, but he doesn’t flaunt it. His investment portfolio is about as daring as a wardrobe full of turtlenecks. Autopsy noted among other things that he double-knotted his shoes.”

“And what misfortune befell him that he required an autopsy?” Storm asked.

Jones slid the remote control to Agent Rodriguez, who resumed the narrative: “Five days ago, Kornblum didn’t show up for work, didn’t answer his cell phone, didn’t answer his e-mail, nothing. This is a man who hadn’t missed a day of work in thirteen years and never went more than two waking hours without checking in with someone. He was Mr. Responsible, so his people were concerned right away. When it was discovered his kids didn’t show up at school and his wife had missed a hair appointment, the Nordrhein-Westfalen Landespolizei were dispatched to his home in Bad Godesberg. They found this.”

Another projector emerged from the ceiling. Crime scene photographs started flashing up on a screen on the far wall. It was all Storm could do not to avert his eyes. The children, both in their early teens, had been killed in their beds, apparently in their sleep. Powder burns around their entry wounds suggested point-blank shots. Their pillows were blood-soaked.