11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Vertebrate Digital

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

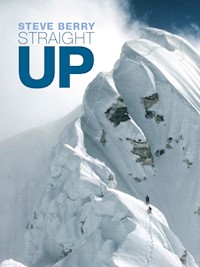

Born in the foothills close to the Himalaya Steve Berry had from an early age an urge to become a traveller, an adventurer, an explorer, and until the age of thirty-eight years he tried hard to satisfy two opposing forces. Half of him wanted to find a satisfactory career path while the other half wanted to be free and specifically explore the Himalaya. In the end he found a compromise to satisfy both needs. In 1987 with his climbing friend Steve Bell he founded Himalayan Kingdoms, a travel company specialising in trekking and expedition holidays. This book is a collection of stories from his early expeditions to the Himalaya prior to 1987. There are tales of encounters with bears, escapes from avalanches, summit successes and failures, love stories mystical connections, Himalayan storms, near death accidents, raw travel across the Indian sub-continent, and grapples with bureaucracy. It is told warts and all. It starts with tales of youthful naivety in the mountains of Himachal Pradesh, progresses to what Steve describes as his best ever adventure, the first British ascent of Nun, 7,135m/23,410ft, in Kashmir, and finishes with the truth of what happened on the failed attempt to climb Bhutan's highest peak, Gangkar Punsum, 7550m/24,770ft. Of Straight Up Steve says: 'I just really wanted people to enjoy reading of our adventures the way they were.'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Straight Up

Himalayan Tales of the Unexpected

Steve Berry

Straight Up

Himalayan Tales of the Unexpected

Steve Berry

.

.

Himalayan Kingdoms Ltd.

www.mountainkingdoms.com

Cover

Title

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1 – The Very First Time

Chapter 2 – Better Luck Next Time

Chapter 3 – Towards the Crystal Willow

Chapter 4 – The Drinks Officer and a White Needle

Chapter 5 – Politics and the Climb of Nun

Chapter 6 – Finishing the job

Chapter 7 – The Austrian Chiefs, and the Avalanche

Chapter 8 – The Professor and the Kingdom of Zanskar

Chapter 9 – Towards the Turquoise Mountain

Chapter 10 – The honest Bank Manager and other Dilemmas

Chapter 11 – So Near and yet so Far

Chapter 12 – Getting into Bhutan

Chapter 13 – Some of the Truth

Chapter 14 – Trouble along the Way

Chapter 15 – A Beginning

Chapter 16 – The Climbing

Chapter 17 – Rejection

Chapter 18 – Alone with Ginette

Chapter 19 – Waiting

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Photographs

— Contents —

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1 The Very First Time

Chapter 2 Better Luck Next Time

Chapter 3 Towards the Crystal Willow

Chapter 4 The Drinks Officer and a White Needle

Chapter 5 Politics and the Climb of Nun

Chapter 6 Finishing the Job

Chapter 7 The Austrian Chiefs, and the Avalanche

Chapter 8 The Professor and the Kingdom of Zanskar

Chapter 9 Towards the Turquoise Mountain

Chapter 10 The Honest Bank Manager and other Dilemmas

Chapter 11 So Near and Yet So Far

Chapter 12 Getting into Bhutan

Chapter 13 Some of the Truth

Chapter 14 Trouble along the Way

Chapter 15 A Beginning

Chapter 16 The Climbing

Chapter 17 Rejection

Chapter 18 Alone with Ginette

Chapter 19 Waiting

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Photographs

To my father who gave me

my love of mountains

Map of the Himalaya.

Illustration: Simon Norris.

Map of Nepal.

Illustration: Simon Norris.

Map of Bhutan.

Illustration: Simon Norris.

— Foreword —

I have known Steve Berry now for 12 years. My first meeting with Steve was at Bristol when he invited me to do a lecture for the Wilderness Lectures programme. After the show I stayed at Steve’s house and received such warm hospitality, just like we offer here at our Sherpa home. I felt like I had known Steve for a long time even though I had only just met him. It was a great moment for me meeting Steve and hearing all about his adventures of climbing in the Himalaya, and meeting his lovely family.

Steve is a mountaineer who has climbed peaks in the Himalaya from India and Bhutan to Nepal. He was the first British climber to ascend Mount Nun in 1981, the highest mountain in Northern India, in the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Himalaya have a way of entrancing those who enter their orbit; to create a spiritual adventure and fond memories that last for a lifetime. This is not merely because they are the highest mountains in the world, but also because of the dimensions of spirituality and the special grace of force that the Himalayan peaks have to offer.

Steve, who has been trekking and climbing in the Himalaya many decades, admirably captures the joy and the beauty of the mountains in this book. He explains his chapters from a different vantage point and with great feeling. He gives a very honest account of his journeys that have taken him from Mount Nun and his father’s expedition, to the Turquoise Mountain Cho Oyu. His love for the Bhutan Mountains and its people are so special in his life.

As I read this book and looked at the images, I was reminded of my own journeys and climbs in my beloved Himalaya and Antarctica. It’s a great pleasure to see these mountains and the people who live under the shadows of the Himalaya being brought to a large number of people through the pages of Steve’s book. It is only through knowing of the beautiful places of our world that people like Steve get inspired to live in that world more responsibly and caringly, preserving such grandeur and beauty for generations to come.

I congratulate Steve for his wonderful stories that he has expressed with true honesty, purely for the love of the Himalaya and its people, whom he has admired and made wonderful friends amongst, and continues to do so. I am sure this book will be a source of positive inspiration for many readers..

Tashi Tenzing Grandson of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and three times Everest summiteer

– Introduction –

On the face of it the real world seems so ordinary, normal, simple even. There are the trees and their leaves, grass, plants and animals, insects, the earth itself, clouds and rain, stone and sky. So it would seem with the lives we have; we eat, we defecate, we sleep, we breathe, we move, we reproduce. Why should there be anything fantastical beyond this natural world? Why shouldn’t mankind have stuck with hunting, growing things and protecting himself from his neighbours? After all that’s what all the other creatures do. On the face of it everything’s so normal. It should be normal, but then again it’s not. Reality in fact is not the slightest bit normal. The universe stretches to infinity in every direction, crowded with an infinite number of galaxies each containing such vast numbers of stars and solar systems that our stretched minds find it hard to cope. In the other direction our scientists tell us that everything is made of invisibly small spinning objects whose vast numbers are even more difficult to comprehend. Abnoreality is a very big thing indeed.

Well, even if reality is composed of an incomprehensible collection of scattered matter, that could be soaked up by sanity, provided it all followed a set of logical rules, but there do appear to be some pretty strange things going on behind the scenes. Life has designed some staggeringly clever things which for my money cannot just be passed off by theories of natural selection. At an atomic level DNA shows an intelligent manipulation of matter. This process of eggs and sperm coming together in a variety of inventive ways; that’s not just luck, and sorry, but I don’t believe that a billion creatures flung themselves off cliffs flapping their appendages until one day two of them rose into the air and started breeding as seagulls. Behind a front of normality, which we grow up to so readily accept, there are stranger forces at work.

Not just in the matter of creation, or the creation of matter, but in how the past, present and future are connected, how we as people are joined in inexplicably odd ways, how fate has a hand in normality, how every now and then there are solid markers to tell us we are going in the right direction, or not, as the case may be. How occasionally there are outrageous experiences which occur to dumbfound our conditioned selves. Telepathy, astral travel, levitation, communication with the afterlife, faith healing, visions of the future to name but one or two talents our motley race chances on from time to time. Even through our ‘science’ we have almost inadvertently discovered we can speak to each other by the use of fashionable handsets, freeze time on celluloid, send moving pictures at the speed of light, look in detail at the insides of our bodies, and catapult metal objects to the far reaches of our solar system and beyond.

So why should we expect things to be ‘normal’, they patently are not, and we have every right to expect extraordinary forces to be working on a plan for our lives. Had I been asking these questions in Mediaeval times I no doubt would have believed God had the answers. Now all I see is a host of arrogant religions claiming ownership of the patents to the infinite, and fighting each other for the right to exist. A whiff of the absolute no doubt touches the mental nostrils of every culture but the existence of one God to rule them all; I doubt it. All the religions have got it wrong and mankind will continue his search for appropriate questions to discover the ultimate truths of the universe. All the tools we have in our individual search for perfection are the subtle power of words, and emotions to set them free. Will exemplary characters emerge wielding words to provide the all powerful answers in the end? Possibly. In any case forget normality; we are now a far cry from the simple, normal life of breeding and farming.

And it seems to me that humankind is never happier than when things are not normal. We spend most of our time in a world of fantasy of one sort or another. We devour anything that is fiction, and chase the ends of imaginary rainbows in the hope of finding a pot of gold that will convey us into some consumer paradise. In our ordinary lives we dream of impossible sexual situations, success that would elevate us to a point of veneration, and personal acts of bravery or charity that would automatically earn us the respect we imagine we deserve. Our television is ninety percent fantasy ten percent poorly presented fact, the biggest blockbuster films are of magical heroes quashing quadruped aliens or vanquishing evil wizards. Barely a moment goes by when we are not absorbed by either our personal fantasies or the fantastical world of others. Even in our sleep when you would think that everyday normality would prevail, we experience detailed phantasmagorical worlds of the bizarre that our waking selves would be incapable of inventing. Not content with the birds and the bees we are continuously tampering with reality, poking it, prodding it, whipping up its potential in the hope we can slow the decay of our houses of flesh, or create the perfect being. The fact is that reality is boring if taken on face value, and mankind slavers for excitement. Mankind feeds on fantasy. We are utterly obsessed by it and our spirits crave more and more.

I think fantasy hits its peak when we are young, especially when hormones and adrenalin have right of way in our veins. The young have blind confidence in their abilities and a sense of indestructibility and close their eyes to the obvious, that big mountains are very dangerous places.

So it was for me, and it was not until long after I started to fulfil my own fantasies of exploring the Himalaya that I was to discover that there especially, not everything is what it seems.

My first climbing memory is of a gnarled old oak tree that grew on the village green right opposite the manor house that we had rented as a family in Kirtlington, Oxfordshire. The village lads would often climb up and into the tree which was so old it was hollow inside. Dad drove some six inch nails into the trunk to help me get up. I must have been only four at the time. The second climbing memory is not so happy.

We had moved to the nearby village of Chesterton and this time had rented the servants’ quarters of an old deserted mansion. One day, aged seven, I tied my younger brother on one end of mum’s washing line and we climbed into yew trees behind the house. As we moved along some branches my brother fell down one side of the branch we were on, and I fell down the other. We were left dangling and screaming for help. Luckily our father heard us and rushed out of the house and cut us down before we died of asphyxiation. We received a sound thrashing with the leather end of a horsewhip. It didn’t put us off though.

We were a solid middle class family with a few skeletons in the closet like everyone else. After all we do live in the real world and nothing is perfect. Dad was a self-made man, who had risen from his illegitimate beginnings from mining stock in Yorkshire to become a Major in the British Army in India during the Second World War, and afterwards to become a chartered surveyor and pillar of the community. He had climbed in the Indian Himalaya during times of leave, and from an early age I remember there were always stories of India, and when he was de-mobbed from the army, many pieces of our furniture had been sent back from Bombay with his kit.

I admired his achievements but hated his Victorian views, his strict discipline and the rather narrow minded, black and white view he had of the world; it led to too much prejudice in my view. He was clever and could be utterly charming, but if you got on the wrong side of him like as not you would find yourself bettered in a court of law with damages and costs to meet. Despite the fact he had lived in India dad also suffered from the typical type of barely concealed colonial racial prejudice that was widespread with his generation. He also held a very low opinion of the mental abilities of Americans. He cared deeply about many other things and I have so far painted much too black a picture of him. He built flats for the elderly, rescued buildings he thought had architectural merit from being bulldozed, and sat on the Town Council. He absolutely loved our mother who in fairness had been sent from heaven to look after us. She came from a one time wealthy family who had made their money from a fleet of trawlers which operated out of Grimsby and Fleetwood. The fleet had not been modernised and the money was fast dissipating, but still they lived a rather grand style of life, and granny played canasta once a week and all her friends wore furs. Grandpa Olliff had been gassed three times in the First World War and never really worked again afterwards, but I digress.

Dad certainly loved the mountains most of all. Weeks away in North Wales were the only time we got on well together. We ticked off all the peaks over two thousand feet listed in a book by W. A. Poucher, always finishing with an ascent of Snowdon. We stayed at Mrs. William’s farmhouse which had no electricity and a toilet built over a stream, and I remember after one long day walking in the hills dad drinking twenty seven cups of tea from Mrs. William’s bone china tea cups.

When we were living at Kirtlington, and I must still have only been five, dad came home after a climbing trip to North Wales, and taking off his shirt revealed that he was black and blue all over. He had fallen off trying to lead Munich Climb on Tryfan and with the rope only having been tied round his waist had sustained a lot of bruising.

He stopped climbing after that until I was seventeen when mum let him take me on my first proper rock climb, on the proviso that we employed a professional guide. Ron James took us up The Parson’s Nose on Crib y Ddysgl and from that day on I couldn’t wait to do more.

The following day in fact dad and his best friend Dr. Plint both failed to lead Pulpit Route on Tryfan and I pleaded to have a go. Successfully reaching the belay after a steep little wall I was as high as a kite, and thereafter gave up tennis, cricket and athletics and spent any spare time climbing.

One of the main reasons for me moving to Bristol aged twenty one was because I knew I would have the Avon Gorge on my doorstep. It didn’t take long to make friends with the bunch of young climbers who were always hanging around Stan’s tea van in the car park below the main area of limestone cliffs. Some became friends for life, but later quite a few died in the mountains. We were wild and free, couldn’t care less about authority, drove our cars far too fast, smashed them up too often, partied, smoked cannabis, ate magic mushrooms, and competed with each other for the physical affections of the dismally small number of females who were attracted by our company. We spent all our spare time rock-climbing and discussing individual moves in great detail in the pub afterwards.

Life went on like this for a good many years. Some of our number became world class rock-climbers in their own right, and before convention and matrimony infiltrated the group, we gave free rein to ambition. We thrashed an assortment of old bangers across France to the Alps, we climbed above topless beaches near St. Tropez, and we played with our American cousins at the Mecca that all rock-climbers aspire to, Yosemite, California. Eventually, of course, we began to fantasise about the Himalaya and this book is a collection of some of those adventures.

I have tried to tell the truth as far as I can. I mean why the hell not; the truth is the truth after all, and I have never pretended to be a starched white shirt. I have, however, not revealed certain rumours which might hurt living relatives of friends who have died in the big hills, or which would spoil my own relations with certain foreign governments.

— Chapter 1 —

The Very First Time

The bear had gone through the only patch of snow where we could pitch a tent just a few hours before. We knew this for certain as it had snowed in the morning as Matt and I had laboured three thousand feet, with crucifying loads, from our last camp in the Solang Nala valley in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The bear prints were still crisp.

Before we set off Matt had given me a convincing impression of knowing where he was going, so I followed him out of the dripping, soggy forest, up through the snow line and over the glacial moraine. Descending a thousand feet we had found a level place for our tent, but the fresh snow was criss-crossed by bear tracks. We had no choice – we had had to camp there. It was the only place, and it would soon be dark. The bear’s imprint was almost as big as my mountaineering boot and you could clearly see the sharp claw marks. We were already two thousand feet above the snow line and were amazed to see the tracks leading off and up several thousand feet more above us. We concluded that it must have come this way heading north to cross the Tentu Pass, 16,000ft, which gives access into another valley system to the west.

Another thing that amazed us was that, after examining the tracks, it was clear that the bear walked for long distances upright. Evenly spaced prints, not two on the right followed by two on the left. We knew nothing about bears – did they walk long distances upright? Could it perhaps be a Yeti? The paw shape and the claw marks were perfectly visible. It had to be a bear.

We pitched our two-man tent on a stamped-out snow platform, cooked a frugal supper, and organised our climbing gear for the morning. Excitement, adrenalin and fear fought for space in our young heads. There we were, hoping to climb an 18,000ft/5,500 metre mountain, days from the nearest village, camped on the snow on the only level spot for miles, surrounded by bear tracks that could only have been made a few hours previously. We were trespassers, and not far away was an irresistibly powerful and savage animal with big teeth and sharp claws. Finally, we rationed ourselves to a few slugs from our small plastic bottle of whisky before making our preparations in case the bear came back. We wrapped the heads of our two ice axes with handkerchiefs, soaked them with some of our precious petrol, and propped them in the awning with matches nearby. We were laughing a lot by now.

This was India and we were just two young, fairly impoverished men far from home. We had only been able to afford the services of two porters, who carried our kit up to the end of the valley, and had then departed. We also knew for a fact that there were bears in the area as we had already had one encounter. At the end of the first day I had gone for a walk on my own above camp and seen two in a meadow about a quarter of a mile away. I had backed down the hill carefully without them spotting me. The local people in the town of Manali had told us several frightening stories about the ‘Lal Balu’, or red bear. Of how a local woman had been abducted by a male bear and had lived as its wife for several years before escaping. Of how people who had gone for a walk in the woods on their own had never been seen again – eaten by the bears it was said. To be honest we had counted on them not being above the snowline.

It was my father’s influence that had brought me to India. He had served there in the war and during his leave had ventured into the Himalaya. My brother and I grew up with stories of his adventures in those privileged days of the Raj when a young British officer could wangle the use of army trucks, lay his hands on expedition kit, and be entertained in grand style by local dignitaries. As children we had rummaged through tea trunks in our loft and pulled out his old expedition gear, pretending to be brave explorers. In his rather obsessive way there were excessively annotated maps, expedition reports, photo albums of his climbs and copies of the Himalayan Club Journal, with more copious notes in the margin. The romance had rubbed off on me, and from a very early age I had made a solemn promise to myself that one day I too would go exploring in the greatest mountain range on earth.

For a long time normal life interfered with this ambition. I had to study, find a job, buy a house, but with no wife in prospect at the age of twenty eight, and with rents to cover my mortgage, I decided it was now or never. Unfortunately my friends in the Bristol rock- climbing circle were all out of funds, or tied down, except one – my regular climbing partner, Matt Peacock. Although his appearance was utterly conventional Matt led a very different life to most. He had rebelled against his father’s desire that he become a bank manager, and instead had followed a life of working night shifts in a bakery, six months at a stretch, and having saved enough he would then travel alone throughout India. Six months work, six months travel in India – that’s how he had been living for some years now. He would be my Indian guru; he knew stuff that would see us out of tight corners. He knew all the scams conmen would try to pull on us, and his knowledge of backstreets and bazaars, the workings of Indian road and rail, and how to bargain with rickshaw drivers was an added bonus. Besides which I knew that in Matt’s company I would live high on laughter. Behind National Health glasses was a mystic, a madman, a prankster and a very talented climber.

Anyway Matt had persuaded me that he knew a couple of ‘easy’ peaks just north of Manali, that shambolic Indian hill station popular with hippies, which is surrounded by forests, terraced hillsides and pretty villages, and a stone’s throw from the mountains of my father’s black and white photographs. That place I had so long wanted to reach. I had handed in my notice to Hartnell Taylor and Cook, a fine upstanding firm of surveyors, purchased a ticket on Iraqi Air from a decidedly shady bucket shop, and told my tenants I would be back, God willing, in three months. I had made a will which stated that in the event of my untimely demise, my friends would have to perform a variety of outrageous tasks to get a share of my meagre estate. I had said fond farewells to my despairing and worried parents, and arranged to meet Matt in Delhi. He was as usual mid way through another huge tour of his beloved India.

Iraqi Air had taken off, landed with a technical fault, taken off again and not worsened the airline’s safety record by making it all the way to Delhi, via Baghdad where the airport was being repaired after a bomb blast. I disembarked with an Indian gentleman who was smuggling in watches by wearing scores of them under his clothes, on both arms and legs. This was 1977 long before metal detectors had become the bain of air travel. Leaving the Jumbo the heat hit me with the force akin to opening an oven door. India is a shock from the word go.

Here is how it was – we had very little money between us and so every rupee seemed important. We argued with the rickshaw boys until sometimes they would drive off in disgust, we stayed in hotels where rats ran across the end of the room, we got bitten by bed bugs, and we ate our food from street vendors. Matt was an old India hand and well-acclimatised, but within forty eight hours I was curled up in a foetal position wishing I had not been tempted by the sweet cakes in the market. However, the train tickets to Chandigarh were already bought and Matt shepherded me through the heat and the crowds and onto a steam train heading north. I literally rolled off the train at Chandigarh where an old Indian gentleman befriended us and guided us to the First Class Waiting Room, while he found us a taxi and took us to a hotel. Soon I was tucked up in bed feeling like death. I lay there for two days, in between all too frequent visits to the bathroom, and our old Indian friend came in each day bringing us bananas. We found he could quote from memory huge chunks of Shakespeare. While serving in the Indian Army he had joined the Drama Society and had acted in King Lear. Having studied the play at school I knew his renditions were word perfect. Finally, having expertly made us his friend for life he made his pitch for a handout. How could we refuse. From the sweltering plains we had then travelled twelve hours through the foothills on a public bus to Manali. There had been punctures and landslides on the way, but the most serious equipment failure of the battered, vomit-covered bus was the silencing of the Italian triple air horns. As these were in constant use it was rather important that they were fixed!

Arrive in Manali we eventually did and, after one flea bitten hotel, we shifted to the local Youth Hostel, next to a small shanty town of Tibetan refugees, whose dogs frequently harassed us. There we settled for eleven days and, in between bouts of bad weather and illness, we prepared our lazy bodies for our first high altitude climb of an 18,000 ft mountain called Ladakhi Peak, by suitably punishing day walks in the foothills. Finally though we had to tear ourselves away from the flesh pots, and having hired two porters to help carry to the snowline, set off on our first Himalayan climb.

The night was dark, extremely dark, and not a breath of wind even rustled the tent. Altitude, whisky and childish humour had meant we had laughed ourselves to a standstill. We had used our two favourite camp games. The first was taking it in turns to invent more and more ridiculous ways of crossing the Sahara desert, while the other was to describe in as much detail as possible our own favourite food dishes. When you are starving on a diet of rehydrated food and powdered mash, and have been away from home for some weeks, this is an intensely painful, but hilariously funny experience. The object of the game is to find a simple English dish, such as treacle tart covered in double Cornish cream, which will reduce your partner to a writhing heap, begging for mercy. We had finished the whisky and had all but drifted off to sleep when suddenly the tent shook uncontrollably.

I remember lying as still as possible, but at the same time fumbling in quiet desperation trying to find the matches, expecting a painful, ignominious death at any second. The joke was on us, however, for all it was was a freak but powerful wind blasting down the mountainside without warning.

We were up next day at 4.00 a.m. climbing in earnest now, cramponing up the frozen snow slopes, our tent receding to a small dot below us. The incredibly steep and fierce peak of Hanuman Tibba opposite us, climbed by the famous Italian, Riccardo Cassin, made our own objective seem humble in comparison. Nevertheless Ladakhi Peak at 18,000ft/5,500 metres towering above us, looked quite hard enough thank you. We climbed an easy gully and headed up a fairly broad rib. Matt’s old leather boots were pretty useless and we twice had to stop to warm up his feet. At about 14,500ft/4,400 metres we stopped and chopped out a platform for the tent, which we were intending to bring up tomorrow. By the time we had finished this it was late morning and we could see dark, threatening clouds rolling in from the south east. We hurried down to the safety of our shelter. No sooner had we arrived when it started to snow. That night the storm reached its peak and at one point lightning was flashing, on average, every ten seconds. Avalanches thundered down nearby Hanuman Tibba – frightening yet exciting. The sheer volume of snow that fell was incredible, and at 3.30 a.m. we decided there was a clear and present danger of us being buried alive. Sleepily and in sub zero temperatures we donned our gear and forced our way out into the thigh deep drifts. For an hour and a half, by the light of our head torches, we worked to clear the tent, a process that was to be repeated many times in the hours that followed. After forty five hours in the tent, and with the consolidated snow four feet deep around us and still falling we decided we had to leave. The food would soon enough run out and we might as well abandon our attempt at Ladakhi Peak. At 8.30 a.m. on 25th April we packed, took down the tent and prepared to leave. Already Matt’s feet were feeling numb and I spent time warming them on my bare stomach – an act that is easy to state in a sentence but involved considerable pain and suffering on both our parts!