Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

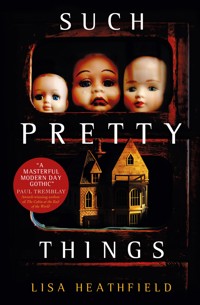

A terrifying story of ghosts and grief, perfect for fans of Shirley Jackon's The Haunting of Hill House and Henry James The Turn of the Screw, in award-winning author Lisa Heathfield s first adult novel. Following their mother's accident, Clara and Stephen are sent to stay with their aunt and uncle. It's a summer to explore the remote house, the walled garden and woods. Beyond it all the loch sits, silent and waiting. Auntie has wanted them for so long - real children with hair to brush and arms to slip into the clothes made just for them. All those hours washing, polishing, preparing beds and pickling fruit and now Clara and Stephen are here, like a miracle, on her doorstep. But as they explore their new home, the children uncover ghosts Auntie buried long ago. As their worlds collide, Clara and Auntie struggle for control. And every day they spend there, Clara can feel unknown forces changing her brother. Haunted and bewildered, this hastily formed family begins to tear itself apart.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 354

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“A masterful modern day Gothic that is dread inducing and melancholic in equal measure,Such Pretty Thingsis a thoughtful rumination on the wonder and horror of grief, of what it can become. By the end, holy hell, the book is a fist that slowly closes around your heart and squeezes.”

Paul Tremblay, award-winning author of Cabin at the End of the World

“A wonderfully creepy and unsettling account of the terrors of a child trapped in an uncertain adult world. The suspense grows as that world becomes increasingly untrustworthy and dangerous, resulting in the steady disintegration of normality. A terrific read.”

Alison Littlewood, author of The Cold Season and The Cottingley Cuckoos

“A masterful slow burn... elegantly crafted and horribly powerful.”

Ally Wilkes, author of All the White Spaces

“A brutally, searingly bleak exploration of loss and grief, with finely drawn characters and lovely echoes ofTurn of the Screw.”

James Brogden, author of Hekla’s Children, The Hollow Tree and more

“A gorgeously Gothic tale of children struggling to deal with their grief and assimilate to an oddly unsettling new environment fraught with a danger they sense but can’t quite grasp. Unnerving and melancholy, this book will hold your heart spellbound.”

Marie O’Regan, author of The Last Ghost and Other Stories, editor of Wonderland and Cursed

“Treads the fine line between nostalgic creepiness harking back to the classics and modern pacing, with believable characters you really care about. Not to be missed!”

Paul Kane, bestselling and award-winning author of Sherlock Homes and the Servants of Hell, Before and Arcana

SUCHPRETTYTHINGS

LISA HEATHFIELD

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Such Pretty Things

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095623

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095630

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Lisa Heathfield 2021

Lisa Heathfield asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Lucy Howe – for bringing extra sunshine to the world

SCOTLAND, 1955

1

Clara sees the trees sticky with sunlight. She can taste heat on the roof of her mouth, her tongue sitting close to her throat as she breathes in. She doesn’t mean to open the car window, knowing only that her fingers find the handle slippery as she turns it.

‘Keep it closed,’ her father says, his voice marred with the same slick of tar that’s been there since her mother’s accident.

‘It’s too hot,’ she says. Can’t you tell, she wants to add.

She feels his eyes watching her in the rear-view mirror, looking from her to the road, to her brother, to the road. Beside her, Stephen traces his finger on the glass, whispering something only he can hear.

‘What are you doing, Stevie?’ she asks, using the material of her dress to brush the crease at the back of her knee.

‘It’s an antler,’ he replies.

‘You saw a deer?’

‘It was on the road,’ he says.

Clara doesn’t remember the animal, although she’s sure she would have seen it if it had been there. There’s been nothing to do for hours but stare out as the world changed; the streets she’s always known – the close-knit houses, the lamp-posts, the bus stop – disappearing behind them until the homes and shops were replaced by endless, endless fields and trees. She hasn’t even been able to draw, the jagged lines of her pencil in her sketchbook making her ill.

‘Stop kicking my seat, Stephen,’ their father says.

‘I’m bored.’ Stephen’s scowl is instant, exaggerated, his feet a steady pendulum beating a rhythm that Clara knows must grate between their father’s teeth.

Her father takes his left hand from the steering wheel and wipes his palm across the back of his neck. The speckled line of dirt on the fold in his collar makes her suddenly, crushingly sad; if the fire hadn’t happened, then their mother would have washed it. She’d have been able to stand in the kitchen, pressing the iron flat onto the shirt. Clara thinks of the heat in the hospital room, the starched bed-linen, the tubes unceremoniously pushed into her mother. The degradation of lying motionless as strangers prodded her skin.

‘You must do as you’re told when you’re with them,’ their father says. He grips the steering wheel again, Clara feeling his tension in her own shoulders, a subtle grasp of fingers that aren’t there. ‘It’s good of them to take you on.’

He’d told them only yesterday, how he couldn’t keep working and look after them. How someone had to pay the bills. Your aunt and uncle have the time and the space. I don’t know who else to ask. Stephen’s tantrum. Their home filled by their father’s resulting bellow, the echo of which Clara still feels deep in her core.

‘I don’t want to stay with people I don’t know,’ Stephen says.

‘They’re not just people. They’re family.’

Who we haven’t even met, Clara nearly says.

She looks out of the window as their car breaks free from the trees, at a marshy stretch where the grass slides into darkened dips and purple thistles rise up in hazy clusters. Beyond that, there’s the silent roar of mountains, their outline picked out in thick, grey ink.

‘See those, Stevie?’ she says. ‘They’ll be ours to explore.’

He forgets his anger. ‘Did mummy go there?’

‘Maybe.’ But it’s impossible for Clara to grasp, their mother as a child, her footsteps running in and out of the heather.

Their father steers the car from the road, stops in front of a gate. On a post, the name Ballechin is written in faded blue paint, yet there’s no sign of the house from here. The children watch as he gets out, arches his back with his arms above his head before he opens the gate, pushing it far enough so that it catches in the long grass. He brushes his hands together as he gets back in.

‘Let’s go and meet them.’

It’s a narrow drive and their father curses as he steers around ruts that threaten to scratch the vehicle. On either side there are thick branches with early blackberries twisting and looping among them.

‘Can we pick some?’ Clara asks.

‘We can’t,’ her father replies. ‘They’ll be waiting.’

Clara catches glimpses of brick between the trees, sees the elbow of a window’s edge through parted leaves. From here, she can tell that Ballechin isn’t a small house and as it steps out from behind the shadows of the pines, she loves it immediately – the window frames with glass cut neatly into separate squares, the curved porch supporting a honeysuckle, surrounding a front door made of dark wood. Roof tiles slant down, holding two tall chimneys and a pair of round windows nestled so far back that they’re almost impossible to see.

Gravel crunches under the car’s wheels before it stops and, as their father turns off the engine, silence takes over the air.

‘Did mummy really live here?’ Stephen asks.

‘Yes.’ Their father laughs and Clara notices how his shoulders relax, as though the strings that have been forcing them up have been cut.

‘What’s that?’ Stephen is pointing to a small footprint of grass with a stone column at its centre. It’s no higher than Clara’s waist, with a metal fin balanced on the top. Part of her wants to lick the metal, to taste it on her tongue.

‘It’s a sundial,’ their father says. ‘Although I doubt it works very well, surrounded by so many trees.’

‘It tells the time,’ Clara tells Stephen, but already he’s looking elsewhere, at a vegetable patch that runs away around the corner of the house.

‘There she is.’ Their father’s seat rubs quietly as he turns to his children and they all look to the woman standing on the front doorstep with an apron tied tight around her waist, the red poppies on it smothered by the folds of the material. ‘Come on,’ her father says, pushing up the middle of his spectacles. ‘We can’t keep your aunt waiting.’

Stephen scrambles from the car, the blur of his eight-year-old self already rushing towards Ballechin, his arms reaching forward. Clara wants to follow him, but for a moment she finds it difficult to move, instead watching the flower bed nestled along the length of the house, where fuchsia bushes reach high enough to touch the windows. She feels a need to pop the red buds between her fingers.

‘Clara?’ It’s her father’s voice, bent slightly with irritation. She picks up her satchel, puts it over her shoulder and gets out of the car, to see Stephen standing close to their aunt. Clara ambles over the gravel to them, struck by the mismatched smells of honeysuckle and soap.

‘They’re beautiful,’ Auntie says. She crouches as though to hug Stephen, but his wide eyes make her hesitate and embarrassment settles among them all. Their father’s cough breaks through it.

‘That’s kind of you,’ he says, his hand on Clara’s shoulder.

Auntie seems to struggle with the right thing to do and her smile begins to falter with the effort.

‘Do you have any luggage?’

‘The suitcase is in the boot.’ And their father steps away from them to return to the car.

Clara looks towards the vegetable patch, where the runner beans overstretch their bamboo sticks, slumped leaves interspersed with almost glowing orange flowers. She’d like to go and sit among the plants, to draw a picture of their stillness.

‘I’ve brought my toys.’ Stephen stands so close to Auntie that his fingers brush against the material of her skirt.

‘We’ll find space for your things.’ She watches them in a way that Clara has never seen before, as though she and Stephen are some sort of miracle standing on her doorstep. The feeling slips under her skin and she thinks that perhaps she can be happy here.

‘I’m Clara,’ she says, almost laughing at her desire to curtsey.

‘Clara,’ Auntie echoes. ‘And how old are you?’

‘I was fourteen two weeks ago.’

‘Of course,’ Auntie says. ‘And here’s Stephen.’

‘Does anyone else live here?’ he asks, and Clara knows he’s hoping somehow for other children, secret cousins to appear behind the windows.

‘Only my husband, Warren,’ Auntie says. ‘We’re so happy you’re coming to stay.’

‘How long can we be here?’ Stephen asks.

‘I’ve already told you,’ their father tells him. ‘A few weeks. Perhaps a bit longer.’

Clara only realises she’s biting her nail when she takes her finger from her mouth, reaching over to squeeze her brother’s hand.

‘It’ll be fun,’ she tells him.

As Auntie stares at them again, Clara studies her face, but she can’t find any trace of their mother. Perhaps that’s a good thing. It’ll be easier to stay here if she can pretend that there never even was a fire.

‘So,’ their father says, suitcase in his hand. ‘Shall we go in?’

Auntie looks over at him. ‘You’re staying?’

Clara knows that his laugh is nervous. ‘Only for a breather before I drive back.’

‘I was worried for a moment that I hadn’t made up a room for you.’ Auntie smiles, relief and warmth on her face. ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’

‘I wouldn’t say no.’

Clara has a sudden desire to hold her father’s hand, but he just winks at her as Auntie turns from them and starts to walk through the door.

‘This way.’

And so they follow.

Inside the house it’s surprisingly dark, the daylight not quite reaching far enough, the heat left behind. There’s a bright rug, though, a large circle and Clara likes the way that it’s threaded with neat lines of colours. It reminds her of the sun, with Auntie treading around the edge of it as though it might scald her.

‘We’ll take off our shoes here,’ she says, slipping her feet from her own. Stephen looks up at Clara, confused, but when she takes off her shoes, he copies. Auntie straightens the soles into a row.

‘I like your house,’ Stephen says, shifting his weight from one foot to the other.

‘Thank you,’ Auntie replies.

It’s a big hallway with wide stairs in front of them, the ceiling reaching far above. The only piece of furniture is a small table pushed against the wall, a black telephone sitting alone on the top of it. Of the four doors, the only one open is to the right of the staircase, showing Clara a glimpse of a dining room painted dark green, with a table and straight-backed chairs.

Her eyes follow the curve of the banisters as they go up, the balusters carved so finely they look like they could snap.

‘Can we explore?’ Stephen asks.

‘In time,’ their father says.

Clara runs her hands over the skirt of her dress. Just this morning she was in her own home, sounds from the street filtering into every corner, her friend Nancy helping her pack. Their conversations overlapping and clutching together at the idea of so much distance soon to be between them.

‘Should I leave their suitcase here?’ their father asks. Auntie looks around, as if there might be somewhere better than the empty space of floor.

‘I suppose so. Yes. And I’ll bring some tea.’ She steps towards the door on the left, pushing it open. ‘If you could all wait in here, I won’t be long.’

Musty air seeps from the room and even though Clara holds her hand over her mouth, the smell is still there. Stephen doesn’t seem to notice it, running towards the dust motes hanging in the filtered sunlight.

‘Look,’ he says, turning to scatter the fragments.

‘This is a cosy room,’ their father says.

The one sofa has its back to the tall window and there’s a dark red armchair next to an unlit fire. Opposite is a wooden chair with a woollen blanket folded neatly across it. Clara wonders if they might sit here in the evenings and whether she’ll be allowed to choose one of the stories from the shelf that sits snug in the wall. She steps towards it and runs her finger along the books’ spines, imagining taking the one from her satchel and slotting it alongside them.

‘Any interesting ones?’ her father asks, standing next to her now.

‘They look a bit old,’ Clara tells him.

He pulls one out, just a bit. ‘They’ll keep you busy on rainy days.’ ‘I’m sitting here,’ Stephen says, running to the red chair and jumping into it, the leather squeaking as he settles into its arms.

‘Move up,’ Clara tells him, but there’s not enough room for the two of them, so she shifts him onto her lap. She can tell that he doesn’t really want to sit like this, would prefer instead to feel like a little king with his fingers splayed wide on the arms of the chair and it gives Clara a piercing rush of love that he chooses to stay with her. She’s aware that he tiptoes around her sadness, that she’s no longer the sister who makes him laugh by strapping pans to her feet. How that girl is lost somewhere in their mother’s blood-soaked bandages.

Their father sits on the sofa, perched too close to the edge as he looks out of the window. ‘You really are in the middle of nowhere up here. You’ll have fun discovering everything.’

‘Is there definitely a garden?’ Stephen asks.

‘There is. Your mother talked about it a lot.’

Clara listens for echoes of her mother’s childhood voice, but hears only the ticking of the clock on the mantelpiece.

The door opens and Auntie comes in, the slight clatter of the tray betraying the shake in her hands.

‘Oh,’ she says, as she puts it down on the low table in front of them. ‘Two of you in one chair.’

Stephen tries to move from Clara’s lap, but she holds onto him.

‘We’ll be careful not to spill it,’ she says, as Auntie stands straight again, a glass of squash in each hand.

‘I’m sure you’ll be fine.’ She nods. ‘I bought this especially for you.’

Stephen pushes clumsily against his sister, a shock of loneliness brushing past her as he frees himself to sit instead on the sofa next to their father.

‘I’ve been thirsty for hours,’ he says.

Clara smells the orange first and can tell that it’s been made too strong; the first mouthful sticks sweetness to the top of her mouth, the liquid thick as she swallows.

‘Is Warren here?’ their father asks, taking his tea from Auntie.

‘He’ll be home later.’

There’s the quiet again. Clara sits as still as she can to listen to the silence.

‘How is Jane?’ Auntie asks.

Their father rubs his thumb across the china cup he’s holding. ‘As good as can be expected.’

‘She’s still asleep,’ Stephen says and the clock ticks on as Clara remembers the months their mother has been lying unmoving. ‘Do you have a kite?’

‘A kite?’

‘To fly in the garden,’ Stephen says.

‘No. No, we don’t have a kite.’

‘I’m sure there are plenty of other things for you to play with,’ their father says.

‘Yes.’ Auntie nods. ‘We have toys.’ Clara watches as she pulls her smile back into place, that same sense of wonder in her eyes as she looks at them.

‘It’s a big house for just you and Uncle Warren,’ she says.

‘Yes. I suppose it is.’

Stephen wriggles about on the sofa, the liquid dangerously close to spilling.

‘Finish your drink, Stevie,’ Clara says. And he does, his mouth smiling at her through the glass.

‘Do you ever want to move away?’ their father asks.

Auntie looks confused. ‘Why would I?’

Clara thinks that her aunt is somehow offended, but she can’t see how. There’s still so much about the adult world that she doesn’t understand. She feels the line of her age drawn on the earth as she teeters along it, falling at times into the side of childhood and at others slipping into the strange mist of growing-up.

Her father takes a bigger gulp of his tea and Clara wonders if it’s scalded his throat.

‘Have you got children?’ Stephen asks.

‘No,’ Auntie replies. ‘We were never that lucky.’

‘Well now you have two,’ their father says with forced cheeriness. ‘Temporary ones at least.’

‘We’ve been looking forward to it.’

Clara glances up at Auntie when she can, looking for clues of their mother. There are mannerisms, if nothing else, an understated elegance in the way she holds herself. Clara would like to draw her, to find more similarities. For now, she just tries to copy her posture, with her back straight, her own lips barely brushing the rim of her glass.

‘Things must have been difficult for you,’ Auntie says, directing the question to their father. ‘You have to keep working after all. You can’t just stop.’

Their father nods. ‘It will be easier with the children out of the way.’

His blunt words sting Clara and it’s only a kind, knowing smile from Auntie that comforts her.

No one says anything more as they finish their drinks, the sound of Stephen’s heels kicking against the base of the sofa. As soon as their father puts his empty cup onto the saucer, he presses his hands on his knees and stands up, brushing imaginary specks from his arm.

‘Right. I suppose I ought to get going,’ he says. ‘It’s a long drive back and I’d like to make it before dark.’

‘Of course,’ Auntie says, standing too, redoing the bow at the back of her apron. ‘We’ll say goodbye, then.’

Clara sees in Stephen’s eyes a brief flash of fear, of impending homesickness. ‘We’ll be very happy here,’ she says as she picks up her satchel, proud that she’s reassuring all of them gathered in the room.

‘I’m sure you will be,’ their father says, as they follow Auntie into the hallway.

At the front door, he’s slow to put on his shoes again and they watch as he ties each lace.

‘Will you visit us?’ Stephen asks.

‘I’ll try to come next week.’

‘It’s a bit far to travel for a short visit,’ Auntie says.

‘Jane will want me to see the children,’ he tells her.

Clara feels fierce tears pushing at her throat, thinking there’s so much she wants to, and should, say.

‘Are you leaving us now?’ Stephen asks.

‘Yes.’ Their father nods. He takes his spectacles from his face and blows on them, cleaning them on his sleeve before he puts them back on again.

‘Give mummy a kiss from me,’ Clara manages.

‘I will. And you look after your brother.’

‘We’ll telephone you if we need anything,’ Auntie tells him.

‘Good.’ He straightens up, his jaw tight.

Clara thinks that he’ll kiss her, but he doesn’t, only squeezing her shoulder before he strides back across the gravel and gets into his car, pulling the door towards him, closing himself from them. The three of them watch from the front step as the vehicle turns, the engine splitting the clean air. They watch as it disappears around the corner of the drive and they stay like this until they can no longer hear even its whisper on the air.

Clara reaches down for Stephen’s hand and he takes it willingly. She believes they’ll be fine here, but still needs his little soul by her side to steady her.

‘So,’ Auntie says. ‘It’s just us now.’ She clasps her hands in front of her chest like a child.

‘Can we see our bedroom?’ Stephen asks, as he runs back inside the house.

Clara picks up their suitcase from the hallway, before they follow their aunt up the stairs. This close she can see that the varnished balusters are carved with weaving corn too delicate to touch, so she keeps nearer to the wall with its paper of faded flowers.

‘We stay on the carpet running down the middle,’ Auntie says, without glancing back.

Clara is disappointed with herself, even though the rules contradict each other – how there’s a rug downstairs to avoid, yet here she must keep away from the floorboards. But when Auntie stops and turns to look at them, Clara is relieved to see the kindness of her smile.

‘Would you like me to carry that?’ she asks, holding out a hand.

‘No. I’m fine.’ Clara’s answer seems to stall Auntie, flustering the air around her. ‘Thank you.’

‘You must be tired,’ Auntie says.

‘It was ages in the car,’ Stephen tells her.

‘It certainly was.’ Auntie laughs lightly.

‘Clara was sick coming up through the mountains,’ Stephen says. ‘Daddy had to stop so she could upchuck in the bushes.’

Clara drops the suitcase, hoping it’ll hit his foot, but it misses and lands loudly on the floor. Auntie tries to keep smiling as she studies the skin on Clara’s lips.

‘I think you should have a bit of a wash, then,’ she says, her voice forced bright. ‘Don’t you?’

The air is clammy at the top of the stairs, where the wallpaper has given way to wooden panelling and the damp of the surrounding hills has had hundreds of years to seep inside. Above each of the five closed doors hangs a dried posy of flowers, clusters of pale, crisp petals tied with faded ribbons. Clara feels her mother’s fingers on the flowers, sees her pick them to arrange in the shed back home, hears the shattering crackle as the blaze destroys them too.

‘Look, Clara.’ Stephen is pulling her sleeve, dragging her back to Ballechin. ‘We’re high up.’ The smell of smoke drifts away as she peers with him over the banister into the hallway, to the table with the telephone, the colourful rug below.

‘Don’t lean too far,’ Auntie says, encouraging them away and through the door on the right at the top of the stairs. It’s a bathroom, with the day squeezing through the frosted window, leaving patches of sunlight on the walls. The bath is bigger than their one at home and Clara likes the tiles with blue dots that blur when she stares too much.

‘This is a strange basin,’ Stephen says. It sits balanced on a short, wooden cupboard and, without asking, he opens the small doors.

Auntie has a hand stretched out as though she needs to stop him, but when she doesn’t Clara realises that Ballechin is a place where Stephen can be himself, that he’ll be happy and hopefully his regression to tantrums will be a thing of the past.

‘Hold your hands under here,’ Auntie tells her, before she turns the tap to drop water onto the girl’s fingers. Auntie’s knuckles remind Clara of button mushrooms that have been left out of the fridge, withered and hard. ‘Good. And a bit of soap,’ Auntie says, as she rubs Clara’s palms to make sure that all grains of vomit have disappeared. ‘That’s better.’

Clara feels full of gratitude. For so many weeks now, since the fire that almost killed their mother, she’s been thrust into the role of carer, somehow at times even for their father, fumbling through her enforced responsibilities. Yet now she’s being looked after again, and the shock of it threatens the ache of tears in her throat as she shakes her hands free of water and grasps Stephen’s shoulder.

‘Ow,’ Stephen says, squinting up at his sister. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing.’

Auntie gathers Clara’s hands in a towel, looking closely at the fingernails.

‘You bite them,’ she says.

‘I’m trying to stop.’

Auntie smiles at her. ‘It can take time.’ And she starts to pat the fingers dry, each in turn, standing close enough for her skirt to touch Clara’s own.

Maybe she even loves us, Clara wonders, as Auntie blows on the backs of her hands before she hangs the towel straight on its rail. Because we’re not strangers exactly, we’re family.

‘My friend, Nancy, said she’ll buy me a sherbet fountain every week for a month if I manage it.’

‘That’s kind of her,’ Auntie says, reaching for Stephen’s hands. ‘Your turn.’

‘But I wasn’t sick,’ he says.

‘Your hands will still be dirty from the journey.’

‘Can I see my bedroom next?’ Stephen asks, as he holds his hands under the flow of water and lets Auntie dry his skin.

‘Yes,’ Auntie says. ‘You’ll be sharing.’

Clara tries not to show her disappointment. She’s never had a room to herself and she was hoping that here at least she’d have her own place in which to hide.

‘Is it big?’ Stephen asks.

‘Big enough for the two of you.’ Auntie laughs. It’s an unusual sound, here in the light-speckled bathroom.

‘Your house is so big,’ Stephen says.

‘That’s why we need to fill it with children,’ she says, tapping him on his shoulder gently. ‘Follow me, then.’

Out on the landing again, Clara notices for the first time that the knotty grains of the wood wall are only painted to look that way. Up close, she can see the brushstrokes, the different shades of brown. She wants to lick her finger and rub at it to see if it smears, but she senses that Auntie wouldn’t approve, so she clutches the suitcase handle instead.

Ahead of them, at the end of the short corridor, is a window looking out over trees. On the sill sit three ancient-looking dolls, two girls and a boy, and even from here Clara can see the fine detail of their clothes, their lifelike eyes painted onto porcelain skin. She knows she’s too old to play with them and that her friends would definitely tease her if they knew, but she has a desperate urge to go and pick them up, to be a child again.

‘I’m afraid that they’re not for touching,’ Auntie says, following Clara’s gaze. ‘Even though they’re such pretty things.’

‘I don’t even want to,’ Stephen says.

‘Warren and I thought that you’d like the east room. You get the morning sun, so it’s nice and warm.’ Clara sees the slight pleading in her eyes as she opens the third door along. Cooped-up air greets them, before Auntie blinks and walks inside.

There are two beds next to each other, with plumped pillows and matching patchwork counterpanes. They’re similar to one that Clara tried to make at school, with Nancy talking more than sewing as they squinted and pulled thread, lining up the hexagonal patterns. Clara had found the niggling material difficult to pinch and control, but she wishes now that she could have finished it.

Between the beds is a tiny table with a toadstool lamp. The red curve with white spots has been partly cut away to show a family of rabbits in their kitchen in a burrow and Clara isn’t surprised when Stephen rushes towards it, kneeling down to peer inside.

‘I thought you’d like that.’ Auntie laughs and he looks back at her, his face lit up with happiness. Clara wants to ask him to stay still so that she can capture it in a drawing, but he stands and the moment is gone.

The shining wooden floor of this east room holds two rectangular rugs, one for each child. White curtains are hooked back from the window with little red bows. Tucked close to the glass, almost hidden under the curtain’s hem, is a dead fly with its legs held together in prayer. The blue wardrobe in the corner. The little chest of drawers with a vase of flowers placed carefully in the middle.

‘They’re harebells,’ Auntie says when she sees Clara looking. ‘I picked them for you this morning.’

‘Thank you.’ Clara finds it difficult to know how else to reply. The room is so pretty that it disintegrates her disappointment of not being on her own. She just wishes that Nancy were here to see it and envisions her friend spinning wide-eyed circles between the beds.

‘And look what’s here,’ Auntie says, closing the door slightly to show a desk behind it, with two notebooks sitting side-by-side, two new pencils sharpened to a point. Clara wants to pick up one and smell the lead tucked inside. Instead, she turns to the bricked-up fireplace with orange tiles surrounding it and the mantelpiece above, with an ornament of a boy sitting on a rock. His face has been worn thin, his nose hollow and the colour in his eyes rubbed away.

‘What’s that?’ Stephen asks, reluctantly pointing to it.

‘He was mine when I was your age,’ Auntie says. ‘I thought you might like him.’

‘Oh,’ is all Stephen says, frowning at the faded grey of the little boy’s trousers, the chips of china scratched from his arms.

On the wall above the beds there’s a round clock in the middle of two identical paintings – perfect sunsets above perfect hills, each one encased in a heavy gilded frame.

‘They’re difficult to dust,’ Auntie says, nodding towards them, ‘but they’re worth it. Do you think?’

‘Yes,’ Clara replies. Stephen leans his head to see them from a different angle and Clara hopes he won’t say that he’d prefer it if they were motor cars, or at least a train.

‘I made you clothes.’ Auntie sounds like an excited child as she turns the handle on the wardrobe door and opens it. Inside, there’s a row of hanging dresses and little hanging suits. There’s a smell too, like dogs’ skin, and Clara tries to cover her nose and mouth without Auntie noticing. ‘They’re all yours. I hope that you like them.’

Stephen is touching his suits, each in turn. ‘I’ll look just like daddy.’

‘I think you should change before tea,’ Auntie says. ‘We might as well start as we mean to go on.’

‘I’m comfortable as I am,’ Clara says. She knows she won’t like the high necks of lace and the hems that will skim her ankles. ‘Thank you, though,’ she remembers.

Auntie stares straight ahead and Clara can almost see her mind stuttering behind her pale-blue eyes.

‘Maybe tomorrow, then,’ she eventually says, and Clara feels a shade of guilt as Auntie’s shoulders sink with the stone-weight of disappointment. ‘I’ll leave you to settle in for a bit, then.’ She’s twisting her hands awkwardly, her fingers brushing again and again against the apron. She’s picking the poppies, Clara thinks. ‘I’ll call for you when tea is ready.’ And their aunt hurries out, a beetle scurrying away.

‘Have you seen the garden? The grass is in lines.’ Stephen rushes over to try to push up the window, but it wants to keep the stuffy heat trapped inside.

Clara smells the harebells, disappointed at their weak scent, before she goes to stand beside her brother and stare out. It seems more like a park than a garden, big enough to hold a hundred children, with a hedge drawing a neat line across the middle.

In the centre of the lawn is a circular flower bed filled with white flowers.

‘It looks like the moon,’ she says.

There’s a rose-walk leading to an opening in the hedge; beyond that more lawn, before a forest and the steep rise of the mountains. Clara is amazed that she’s here. Before, there were the four of them, but somehow that time has been swept away and life’s unpredictable current has led her to a house in the hills. She puts her finger on the glass and follows where the garden has been mowed, leaving a faint smear that disappears like fog as soon as she lifts her hand away.

‘It must take hours. Do you think they’d let me do it?’ Stephen asks.

‘I’m sure they would.’ There’s a memory, somewhere, for Clara. Only a few months ago, Stephen jumping in their father’s carefully placed grass shavings. Clara’s thoughts echo now with the sound of her brother’s tears from behind their locked bedroom door.

‘Clara?’ Stephen’s voice cuts through the green-smeared skin, the whiskers of their father’s moustache.

‘Yes?’

‘I like this room,’ he says, jumping onto the bed, his joy infectious. ‘And she’s nice, even though she’s a bit old.’

Clara puts her fingers to her lips. ‘She wants to look after us, when she didn’t have to. We’re lucky.’

‘She must have one of those gold hearts,’ Stephen says.

‘Yes, she must.’ Clara is suddenly overwhelmed by gratitude for her aunt, for letting her feel safe, cocooned from the horror that came before.

‘Can we unpack?’ Stephen asks, but before he’s even finished the sentence, he’s racing towards the suitcase and is dragging it across the room.

Clara puts her satchel on her pillow before she helps him lift the suitcase onto his bed, and together they unclasp it and the top springs open. Inside it’s so jumbled with toys that Clara doesn’t know where to look.

‘When did you put these in?’ She’d been the one to pack the bag, the last one to close it.

‘I swapped some things,’ he says, as he reaches past all of the toys to pull out his Walrus. He puts his nose to its fur and inhales deeply.

‘Where are the clothes I packed for you?’

‘There wasn’t enough room for everything.’

‘You can’t only wear the clothes you’ve got on.’

‘I’ve got new ones now.’ And he looks towards the wardrobe.

Clara wants to tell him that the suits will turn him into a stranger, that she doesn’t want him to wear them, but she keeps quiet, worrying that it’ll only burst this new layer of happiness he’s building around him. Instead, she sits on the other bed and stares out of the window, sees how in the distance the hills rise steeply to touch the white sky. Closer to the garden there are so many trees watching back. They can see only her head and shoulders through the glass, but for some reason Clara doesn’t like them knowing that she’s here.

So she lies down, curls tight into a foetus. Sometimes she does this, rucks up the sheets around her, resettling herself in her mother’s stomach again. Even when her mother was better, she liked to pretend she could hear the gentle thud of her mother’s heart. Clara lies like this and if Stephen really looked, he’d see freckles of tears, perfect circles balanced in the corner of her closed eyes. She’s glad to be in this house, she knows she is, but the tears escape to slide across her nose and slip down her cheek.

* * *

Downstairs, Auntie pushes open the wooden door to the kitchen, to where the cast-iron stove waits for her. Above it, the shelf is laid with brass pans that gleam in their order of size. There’s only one small window in here; she sometimes thinks that the room reminds her of a womb, before that thought shrivels up inside her.

She hears the children in their bedroom and thinks of the boy with his earnest expression, the girl with her nervous smile. They’re really here, in her house and the thought makes her heart ache with happiness. It’s exactly as she’d hoped it would feel.

Yet her euphoria fades slightly when she hears their suitcase being dragged across the floor. It took her hours to polish, her knees bruised to the bone, but still she kept dipping her cloth in the tub, rubbing it frantically across the wooden boards.

‘Don’t they know?’ she wonders. ‘How long it took?’

She thinks she will go up there and remind them to be careful, but suddenly the little boy laughs. It’s a sound she can barely remember and it covers her, smothers her, tipping her towards a place she’s forgotten ever existed.

‘Pull yourself together,’ she chides herself.

Hanging on the end of the shelf is a tube of twisted garlic. She notices immediately that a piece of its translucent skin has comeloose, but is calm as she snaps it off, the dry rustle comforting her. She lifts the bin and pops it in, before washing her hands in the deep white sink.

What to cook? She’s planned a stew, but now she’s met the children she’s not so sure. What would they prefer? The children. She has to stand still and concentrate on her breathing, slow down the need to cry and laugh and shout all at once. Instead, she just screws up her fists in glee and stamps her feet excitedly, where no one can see.

‘They’ll like the fish,’ she says out loud. It’s a good dish, peppered with herbs she’s spent the summer drying, hanging in the larder where their smell masks that of Warren’s muddy boots.

The fish has been resting in her fridge in a pot of brine, as her husband likes, the salt sinking even into the wide, round eyes. She worries that the juice is already strong and possibly a taste that they’re not used to.

‘In time,’ she says.

She pulls the two pieces of fish from the tangy water and places them on the wide chopping board. She chooses the right knife, the one she uses only for this, and slices clean along the length of one of the bodies. She can smell the sea from it.

‘Did you swallow the ocean?’ she asks, even though she knows that it can’t reply.

Auntie scrapes the mess from inside it, scooping it up, dropping it into a bag and into the bin, soaping her hands and drying them on the towel hanging from its hook on the wall.

She likes the sound of the fish frying, the sight of them turning from wet pink to white. They shrink so slightly, yet enough for her to see. She hums as she melts butter into the silver scales.

She never thought she could be this happy.

2

There’s a gentle knock on the children’s door. Stephen stops, his hand still on the wooden fire engine as the door opens. Auntie stands in her stockinged feet, her apron, her blouse.

‘Hello,’ Stephen says.

‘Are you settling in?’ Auntie asks, looking into the room.

‘We’ve been unpacking,’ Stephen says, swinging back for her to see. There’s chaos on the floor, toys strewn across the bed.

‘It’s a bit of a mess already.’ Auntie tries to make her voice light, but Clara can tell that the toys scattered around the room are taking up too much space.

‘Oh,’ Stephen says looking around. ‘Is it?’

They sit still amid the awkward silence.

‘I came to tell you that Warren’s home, so I’ll be serving tea soon. You can wash your hands and come down.’

‘Thank you,’ Clara says, hoping that the affection in her voice is enough to make Auntie happy.

* * *