Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

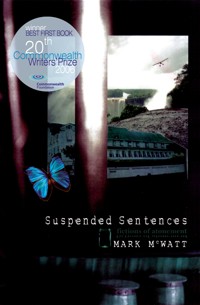

A group of sixth formers vandalize an exclusive Georgetown club on the day of their school leaving, coincidentally also the day of their country's independence. Several of their parents think a lesson is in order and the semblance of a trial is organized. The sentences they are given are suspended provided that they fulfil the task set by their English teacher, who has interceded on their behalf. Each must write a short story that says something about the newly independent Guyana. Years later, Mark McWatt, one of the group, is handed the papers of his old school friend, Victor Nunes, who has disappeared, feared drowned, in the Guyanese interior. The papers contain some of the stories, written before the project collapsed when the group realized the trial was a hoax. As a tribute to Victor Nunes, McWatt decides to collect the rest of the stories from his friends. "Suspended Sentences" is a tour-de-force of invention. The stories, entertaining in their own right, whether supposedly written by eighteen year olds or in later adult life, work not only like Chaucerian tales to reveal their teller, but have an affectionately satirical take on the nature of Guyanese fiction making. By ranging across Guyanese ethnicities, gender and time in the purported authorship of these stories, McWatt creates a richly dialogic work of fiction. And when McWatt apparently slips some of his own biography into a brilliantly comic story of betrayal (that ends in the victim's suicide), but told by another member of the group, the implications of the collection's subtitle, 'Fictions of atonement' become teasingly ambiguous.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUSPENDED SENTENCES:FICTIONS OF ATONEMENT

MARK MCWATT

First published in Great Britain in 2005This ebook edition published 2020 PeepalTree Press Ltd17 King's AvenueLeeds LS6 1QSEngland

Copyright © 2005, 2020Mark McWatt

ISBN 9781845230012 (Print)

ISBN 9781845234966 (Epub)

ISBN 9781845234973 (Mobi)

All rights reservedNo part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction

John Dominic Calistro

Uncle Umberto’s Slippers

Hilary Augusta Sutton

Two Boys Named Basil

Desmond Arthur

Sky

Victor Nunes

Afternoon Without Tears

Valmiki Madramootoo

Alma Fordyce and the Bakoo

Terrence Wong

The Visitor

Geoffrey de Mattis

Still Life: Bougainvilla and Body Parts

Jamila Muneshwar

A Lovesong for Miss Lillian

H.A.L. Seaforth

The Bats of Love

Alex Fonseca

The Tyranny of Influence

Mark McWatt

The Celebration

Remainders

PREFACE

The idea of writing a book of short stories, purportedly by different authors and within a narrative frame, first occurred to me in 1989, when I remember discussing it briefly with David Dabydeen, who thought that it would prove too difficult to maintain distinctions between the styles/voices of the story-tellers. He was (is) probably right, but I wasn’t concerned too much with that, I just wanted to try it if/when I got the chance. A brief (and very immature) version of one of the stories existed since 1969, but the writing of the collection really began in the summer of 1999 in Toronto, when I wrote the first draft of ‘Uncle Umberto’s Slippers’. That story and two others, plus a draft of a fourth, were completed during the month of June, 2000, which I spent as a guest in the small Benedictine Monastery overlooking the Mazaruni river in Guyana. It rained incessantly and I am eternally grateful to Brother Paschal and the other monks for providing me with the time and atmosphere (and that wonderful room looking out on the river) perfect for writing. Over the next two years the plan of the collection was worked out in detail, including the names and personalities of the story-tellers (many modelled loosely on my own college classmates from the mid-sixties) but, although I tinkered a bit with the stories already written, I could not find enough time to write the rest of them until I took sabbatical leave in 2002-03. Two more stories were completed in Toronto before Christmas of 2002 and all the others were written (and the whole book revised) in a little staff flat at the University of Warwick, where I was a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Caribbean Studies from January to July, 2003. I’m very grateful to the Centre and the University for the opportunity to work on several writing projects, prominently including this one.

I was told by a literary agent in London (to whom I had sent the typescript) that, although he personally enjoyed the book of stories, collections of short fiction were not at the time commercially marketable, and I would have to try a small publisher somewhere. I’m not so sure about ‘small’, but Peepal Tree Press – in the person of Jeremy Poynting – agreed to read the book and decided to publish it. For this I am very grateful.

I should thank Joanne Davis, whose delight with the stories she read and whose e-mailed demands for more helped me to keep working on them in the little flat at Warwick. My wife Amparo and my children Ana and Philip also read many of the stories as I finished them, and offered valuable – and sometimes mischievous – comments. I must mention too Margaret McWatt, Wayne McWatt, Ronnie Ramsay, Paschal Jordan, Al Creighton, Hazel Simmons-McDonald and, especially, Gloria Lyn, who all commented usefully on some or all of the stories. David Dabydeen was kind enough to read the completed typescript at a time when he was busy with the finishing touches to his own latest novel. To all these, and any whom I have omitted, I am extremely grateful for the time you took to read my work, for your kind encouragement and your valuable critical comments.

Mark McWatt

INTRODUCTION

This collection of stories is a project I inherited from my cousin Victor Nunes, who disappeared somewhere in the Pomeroon in 1991. His mother, my aunt Margot, sent a message to me to come and see her urgently about something important when I visited Guyana in 1994, and she handed me a battered grey box-file which contained versions of six of the stories and several pages of Victor’s notes and drafts; she told me that he had considered it an important project and a serious obligation, although several of ‘the others’ (and she gave me an accusing look), didn’t seem to share his concern... It was true that I had put off the business of finishing my own story for the collection, in part because I was not convinced that there was ever any legal obligation to do so, but also because Victor had always insisted that mine be the last story in the collection, and that it must tell the tale of what happened on the night of the ‘celebration’ which had resulted in the ‘court case’ and the imposed sentence of writing stories for and about our (at the time) newly independent Guyana. On the other hand, I’d always considered it a good pretext for getting a collection of short stories published, and had never entirely abandoned my part in the project.

I told Aunt Margot – in fact she made me promise solemnly – that I would take over and complete the business of collecting, editing and publishing the stories, if only that they might serve, as she put it, as a fitting memorial to her son who had disappeared overboard in the Pomeroon river and was presumed drowned. The more I read of the material in the box-file (and the more stories and revisions I was able to wring out of the scattered members of the gang), the more enthusiastic I became about seeing the project concluded, but I have not really had the time both to pester the delinquent contributors and to work steadily at the editing, and it is only now, in the third year of a new millennium that I’ve managed to complete the task – some two years after, I might add, the demise of my aunt Margot.

For the rest of this introduction I make use of Victor Nunes’ drafts and jottings (in italics – as opposed to my own interpolations, which are in normal script, and between square brackets). The stories themselves are roughly in the order he had devised, although four of the six stories that he would have read have been revised by their authors at my invitation.

THE GANG

[written in August, 1966]

The authors of these stories were members of a gang of sixth-formers at St. Stanislaus College, most of whom completed their A-level exams in 1966, a month after Guyana achieved independence. It was not a gang in the sense that we had a specific purpose or aim, but rather a group people thrown together by time and circumstance who chose to spend their spare time together, whether it be to study or to lime. I suppose I was leader of the gang by default, as it were, and because I took the trouble to do what minimal organizing was necessary for our various study and other sessions... St. Stanislaus [was in those days] of course a boys’ school, but there were a couple of convent girls eagerly conscripted into our gang, since they attended our sixth form for classes in subjects not taught at the convent. In addition, one of our members was from the lower sixth (principally, I believe, because he happened to be a cousin of mine and tended to hang around with me (us). There was also one member of the gang who was a fifth-former, but was permitted to take A-level Art (at which he was brilliant) and simply assumed that he was entitled thereby to be a member of the gang. Here are brief descriptions of the members of the gang (and therefore the authors of the stories):

[Victor Vibert Nunes – Head boy of the College, leader of the group: serious and scholarly with strong organizational and planning skills; his birth certificate describes him as a ‘mixed native of Guyana’ and he claims that a measure of Amerindian blood is part of that mix. Good at languages which he took at A-level.]

Desmond Stewart Arthur – Desi lives for literature, at which he excels; has written plays which have been performed at college; sensitive, loyal and probably homosexual. He’s like a brother to Hilary Sutton and is specially fond of Nickie Calistro.

Geoffrey Anselm deMattis – Of Portuguese extraction but with dark brown skin; mischievous, inclined to be chubby and brilliant at the sciences. With a surname like his it was in the nature of our Catholic high-school wit to nickname him ‘Nunc’ deMattis. Nunc is an only child with wealthy parents who have more-or-less adopted the gang which is always over at his house.

Hilary Augusta Sutton – ‘High brown’, upper middle-class convent girl from an old Georgetown family which lives in a large wooden house with a tower. She tends to be touchy about class and propriety. She did Maths and Physics in our science sixth.

Jamila Muneshwar – Indian with smooth, beautiful, very dark skin (almost purple, like a jamoon, which is her nickname). She is the daughter of a prominent surgeon and did History and Geography in our sixth form.

Hilton Aubrey Llewellyn Seaforth – Called ‘Prince Hal’ because of his initials; deputy head-boy, tall and dark with stately, aristocratic bearing. Aloof and monumentally calm, Hal is the son of a head-teacher and afraid of no-one. Brilliant at History and Languages and is expected to win a scholarship.

Valmiki Madramootoo – Indian, son of a wealthy businessman who owns several cinemas and nightclubs. Light-skinned, grey-eyed, handsome and epicurean, Val is our expert on films, food and fashion. He did Literature and Modern Languages.

Terrence Gregory Wong – Known as ‘Tennis Roll’ because of his predilection for tennis rolls with cheese. Short, porcupine-haired, Chinese, T. Roll is playful and somewhat naive, though brilliant at Maths and Physics. He is impulsive and always falling in love.

Mark Andrew McWatt – First cousin to V.V. Nunes, Mac is in the lower sixth. The son of a District Commissioner, he knows a lot about the interior and the rivers of Guyana and has been writing poems about these. He is taking Literature, Latin and History.

Alexander Joseph Fonseca – Still a fifth-former, he’s the baby of the group and diminutive to boot (hence his nickname: ‘Smallie’). He makes up for his small stature by being loud and assertive; he’s a prodigious and gifted artist with a foul tongue and a vocation to the priesthood.

John Dominic Calistro – Came into our Sixth form from a school in the interior. During term-time he boards in the home of V.V. Nunes, his cousin, since his parents live in the interior. He’s known as ‘Nickie’ and is always telling stories about his large, half-Amerindian family: parents, uncles, cousins, all of whom live in one huge house. Superstitious, fun-loving and illogical, Nickie did English, Geography and History. The smallest amount of alcohol puts him into a deep sleep.

[I was tempted, at this distance from the sixties, to alter the above brief ‘portraits’ by removing the ethnic references which now seem at least gauche (by most standards, though mild perhaps, in terms of the rampant racial polarization in contemporary Guyana), but I decided that they help date the document and give, I think, an accurate indication of the preoccupations of Georgetown society at the time. Also, I did not want to appear to be quarrelling petulantly with Victor’s descriptions.]

THE COURT CASE

[written in March-April, 1967]

Rather than recount at length the events that took place at the Sports club of the Imperial Bank on Friday 9th July, just over a month after independence, I have asked my cousin Mark McWatt to make his story a narrative of that evening’s happenings and this will be the last ‘story’ in the collection. The reasons for my choice of the author and the position of this story will become evident at the end of the book. [I have no idea what Victor meant by this remark: I did not write my assigned ‘story’ until five years after he had disappeared and I often wonder what he imagined I would say in it]. Suffice it to say that the gang of students listed above met at the club to celebrate both the end of A-level exams and the country’s independence which they could not properly celebrate at the actual time because they were busy studying for the exams – and, due in part to an excess of alcohol and high spirits, they vandalized the club, defacing walls and destroying property. Nine members of the gang were charged with wilful damage of the Bank’s property, although the Bank declined to press charges and it appeared as though a number of parents were involved in ‘arranging’ for the court case that followed a week later. [I was surprised to find that Victor had written this last sentence, because he had always insisted that the court case was genuine and our obligations were clear, while most of the rest of us were convinced, even at that time, that the whole thing was a charade cooked up by some parents and their friends in the judiciary and legal profession to throw a scare into us and to teach us a lesson]

On Saturday morning (17th July) we all turned up in the courtroom of Mr. Justice Chanderband [this was, of course, long before he became Sir Ronald and ascended to his sinecure in the Hague], along with Willow, our Literature teacher and Aubrey Chase, a lawyer and cousin of Hilary Sutton. There was also the police sergeant who went to the club on the night of the vandalism and who served as prosecutor. The judge began by making us all recite our names and addresses, including Mac and Smallie, although they had not been charged since they had gone home early, before any damage was done. Then the charges were read and the sergeant was asked by the judge to expand on the actual damage done:

‘This graffiti, the defacement of the upstairs wall... Can you tell the court, Sergeant, exactly what was written – or rather painted?’

‘Yes, Milord,’ and he opened his notebook and read: ‘There was a two-line sentence as follows: ‘Sir Eustace is an anachronism and Lady Dowding is a tight-assed termagant’ (Sir Eustace, as your lordship is no doubt aware, is the English manager of the Imperial Bank); this was followed by a single word, ‘latifundia’ and then another sentence ‘Don’t pick the blue hibiscus’; finally there was a large blue hibiscus painted on the wall.’

‘Anachronism’, ‘termagant’, ‘latifundia’: were these words correctly spelt, Sergeant?’

‘I believe so, Milord.’

‘Not your run-of-the-mill graffiti artists, eh Sergeant? At least this new country can boast of literate vandals...’ and the sergeant chuckled politely.

All of our other misdeeds that night were recounted in detail: the emptying of over forty bottles of whiskey and other spirits from the bar into the swimming pool, the tipping of a large concrete planter, full of soil and red geraniums, into the pool and the tying up and gagging of the barman, Mr. Dornford and the caretaker/watchman, Mr. Ramkisoon. Judge Chanderband had wonderfully expressive eyebrows and with each item related he managed to contort them into an expression of ever-increasing horror and disbelief. After telling us that these were very serious offences, he asked if any of us had anything to say. We all said, in mournful demeanour and suitably contrite tones, that we had had too much to drink, pointing out that Sir Rupert Dowding himself had generously told the barman to give us whatever we wanted to drink. Val, Nickie and Desmond also made the point that we were carried away by the euphoria of having completed our A-level examinations. The judge wore a tired smile through all this and seemed totally unimpressed. Aubrey Chase then spoke on our behalf, pointing out that we had all admitted our guilt and drunkenness and misbehaviour.

‘Although your lordship might want to consider whether it was not even greater misbehaviour – or at least poor judgment – to give a gang of teenagers the freedom of drinking whatever they wanted from the bar... We should consider, too, the fact that the premises were officially closed for renovations at the time: furniture was covered with tarpaulins, the walls were primed, there were pots of paint lying around and there was an atmosphere of chaos and confusion at the club – which is why there was no adult member present that evening who might have restrained these reckless young people...’

Judge Chanderband gave poor Aubrey a withering look and proceeded to tear his arguments to shreds, pointing out that those charged were all adults, and highly intelligent and educated adults at that, and must take full responsibility for their behaviour since the same would be expected of a bunch of vagrants off the street whose entire lives might be ‘chaos and confusion’. Sir Rupert’s generosity might have been misguided, but could never be blamed for the criminal acts committed by this group of delinquents who certainly knew that what they were doing was wrong... If, my dear Mr. Chase, that kind of crippled argument is the best you can do in defence of these boys, I suggest that it would be better if you said nothing... I understand that there’s a teacher who would like to say something on their behalf?...’ [As I recall it, both judge Chanderband and Aubrey Chase were laughing during this entire exchange, and that contributed to our perception that the entire proceedings were not to be taken seriously]

At this point Willow spoke, supposedly on our behalf, but he began by tearing into us, saying how disappointed he and the other masters were in us and that he felt it as a personal failure. He outlined our past academic achievements as well as the expectations the school had of each of us in the exams, concluding in each case with a version of the following: ‘Of course all that’s now up in the air; it’s anybody’s guess what he will achieve in the exams if he is capable of deviating so widely from the kind of behaviour we had every right to expect of him...’ In fact it was a brilliant performance: he seemed at various points angry, deeply disappointed, shocked and saddened almost to the point of tears by what we had done, while saying at the same time what we were capable of doing and how great a contribution we could have been expected to make to our newly independent country, if only we had not spoiled everything that night by ‘behaving worse than a class of unsupervised second-formers.’ Then, having stolen much of the judge’s thunder, he even managed to suggest what might be imposed on us by way of punishment.

‘I do not plead for them to be excused or pardoned. What they did deserves punishment, and I’m sure, My Lord, that you will not hesitate to impose it; for my part, whatever you do decide on in the way of punishment, I would wish, if possible to add to that the kind of punishment that will force them to realize some of the potential that they seem to have abandoned or negated in one night of drunken recklessness. I know what they are capable of: they are all bright, creative individuals with wonderful imaginations and, instead of defiling their new country by their actions, I’d like to see them being forced to help build it up in an important area, such as it’s creative literature. I’d make each of them write a short story for or about their country and will not consider their debt to their country discharged until the collection of stories (which I feel could be a wonderful collection if they take it seriously) is published and available to their fellow Guyanese...’

Well, we were all in deep shock. [No argument here, Willow’s performance was the one genuine moment of the ‘trial’ and we were all amazed and filled with shame and remorse by what he said; I’ve often thought that those who hastened to write their stories, did so for the English master and not for the judge or the so called court sentence.] The Judge then tried to crush us with sarcasm and anger, but his fulminations were negated by the fact that we were still reeling from Willow’s tirade and, in any case, judge Chanderband just couldn’t match, in our minds, the sense of our unjust defilement of the confidence placed in us by our English master. He ‘sentenced’ us each to two weeks in prison and suspended the sentences for two years on condition that we keep the peace and avoid further trouble and that we each write a short story within that time that could be collected and published in an anthology of nine Guyanese short stories. He said that I, as head boy and leader of the gang, must undertake to collect and edit the stories. [Actually he tried to get Willow to do it, but the teacher insisted that the entire project should be undertaken by the students themselves and it was he who suggested that Victor be made responsible for collecting and editing the stories.] Willow said it should be eleven and not nine short stories, since Mac and Smallie were members of gang and it was ‘accidental’ that they were absent when the mischief took place. The judge replied that he had no objection to the two extra stories, although he could not impose this on the other two as part of a sentence.

That is the origin of this project, therefore, and of my responsibility as editor. Thus far only two stories have been submitted and I am working on my own... [I now think that Victor needed to believe, or to pretend to believe, in the sentences in order to continue collecting the stories; to several of us it was clear that there was no genuine court case, and Hilary told us that Aubrey Chase admitted as much, a few months after. Besides, Nunc overheard his mother telling someone on the phone: ‘Anyway, my dear, we got Ronnie Chanderband to put the fear of God into them in what they think is a real court case – suspended sentences and all...’ When it became my task to extract the remaining stories and revisions from members of the gang after all the years, I did not pretend that it was in order to fulfil a long forgotten sentence, but rather to honour the memory of our leader Victor Nunes, now presumed dead, and to make some contribution to the literature of Guyana, a country which most of us have abandoned and which seems in worse shape now than it was at independence.]

Victor Nunes/Mark McWatt

UNCLE UMBERTO’S SLIPPERS

by Dominic Calistro

Uncle Umberto was my father’s eldest brother and he was well known for two things: the stories he told about ghosts and strange things that happened to him, and his slippers, which were remarkable because of their size. Uncle Umberto had the most enormous feet and could never get them into any shoe that a store would sell. When I was a small boy I remember him trying to wear the ubiquitous rubber flip-flops that we all wore. Uncle Umberto would wear the largest size he could find, but when he stood in them nothing could be seen of the soles, for his large feet completely covered them – only the two tight and straining coloured straps could be seen, emerging from beneath the calloused edges of his flat feet and disappearing between his toes. They never lasted very long and the story goes that Aunt Teresa, his wife, used to buy six pairs at a time, trying to get them all of the same colour so people would not realize how quickly Uncle Umberto’s feet could destroy a pair.

But all that was before Uncle Umberto got his famous slippers. It is said that, on a rare trip to the city, Uncle Umberto stood a whole day by a leather craft stall in the big market and watched a Rasta man make slippers out of bits of car tire and lengths of rawhide strap. When he came home from this trip, Uncle set about making his own unique pair of slippers. It seems that no car tire was wide enough for the sole, so uncle went foraging in the yard of the Public Works Depot in the town and came up with a Firestone truck tire that seemed in fairly good shape, with lots of deeply grooved treads on it – he claimed he ‘signalled’ to the watchman that he was taking it and the watchman waved him through the gate. This he cut up for the soles of his slippers. Because they had to be so long they did not sit flat on the floor, but curled up somewhat at heel and toe, keeping the curved shape of the tire – this was of course when they did not contain Uncle’s vast feet. Each of these soles had three thick, parallel strips of rawhide curving across the front and these kept Uncle Umberto’s feet in the slippers. There were no straps around the heel. Uncle made these slippers to last the rest of his life: they were twenty-two inches long, eight inches wide and nearly two inches thick. The grooves in the treads on the sole were one and a quarter inches deep when I measured them about four years before he died – when I was twelve, and beginning to get interested in my family and its wonderful characters and oddities.

The other detail to be mentioned about the slippers is that Uncle Umberto took the trouble to cut or drill his initials into the thick soles, carving H.I.C., Humberto Ignatius Calistro – the central ‘I’ being about twice the height of the other two letters (he always wrote his name with the ‘H’, but was unreasonably upset if anyone dared to pronounce it. To be on the safe side, we children decided to abandon the H even in the written form of his name, and he seemed quite happy with this). These incised initials always struck me as being completely unnecessary, if their purpose was to indicate ownership, for there could never be another such pair of quarry barges masquerading as footwear anywhere else in the world.

These then became Uncle’s famous badge of recognition – one tended to see the slippers first, and then become aware of his presence. Quite often one didn’t actually have to see them: a muddy tire print on the bridge into Arjune’s rumshop told us that Uncle was in there ‘relaxing with the boys’. At home (we all live together in the huge house my grandmother built over the last thirty years of her life) my father would suddenly say, ‘Umberto coming, you all start dishing up the food’. When we looked enquiringly at him he would shrug and say, ‘I can hear the Firestones coming up the hill’, and soon after we would all hear the wooden stairs protesting unmistakably under the weight of Uncle Umberto’s footfalls.

* * *

My grandfather, whom I never knew, was a seaman; as a youngster he had worked on the government river ferries and coastal steamers, but then, after he’d had two children, and had started quarrelling with my grandmother, he took to going further away on larger ships. Often he would not return for a year or more, but whenever he did he would get my grandmother pregnant and they would start quarrelling and he would be off again, until, in his memory, their painful discord had mellowed into a romantic lovers’ tiff – at which point he would return to start all over again. When he returned after the fourth child, it was supposed to be for good, and he actually married my grandmother as a statement of this intention, but when the fifth child was visible in my grandmother’s stomach, he became so miserable (she said) and looked so trapped and forlorn, that for his own good she threw him out and told him not to come back until he remembered how to be a real man again. In this way their relationship ebbed and flowed like the great rivers that had ruled their lives and fortunes. They had nine children, although it pleased God, as Grandmother said, to reclaim two of them within their first few years of life.

The cycle of Grandfather’s going and coming (and of my grandmother’s pregnancies) was broken when he got into a quarrel in some foreign port and some bad men robbed him of his money, beat him up and left him to die on one of those dark and desperate docklands streets that I was readily able to picture, thanks to my mild addiction to American gangster movies. At least this is the version of the story of his death that they told me when I was a boy. As I grew into a teenager and my ears became more attuned to adult conversations – especially those that are whispered – I began to overhear other versions: that yes, the men had killed him, but it was because he had cheated in a card game and won all their money; that he had really died in a brothel in New Orleans, in bed with a woman of stunning beauty called Lucinda – shot by a jealous rival; even that he had been caught on a ship that was smuggling narcotics into the United States, and was thrown to the sharks by federal agents who boarded the vessel at sea... At any rate he was still quite a young man when he died.

My grandmother mourned her husband for thirty years by embarking on a building project of huge proportions – the house we now lived in. She decided she would move her family out of the unhealthy capital city on the coast and build them a home on a hill overlooking the wide river and the small riverside mining town in which she herself was born. The first section of the house (‘the first Bata shoe box’, as my father puts it) was built by a carpenter friend of my grandmother’s who had hopes of replacing my grandfather in her affections, and ultimately in the home he was building for her. My grandmother allegedly teased and strung him along, like Penelope, until the new house was habitable; then, becoming her own Ulysses, she quarrelled with him in public and sent him packing. The next section of the house was built when Uncle Umberto, the eldest boy, was old enough to build it for her, and for the next twenty years he periodically added on another ‘shoe box’, until the house became as I now know it – a huge two-story structure with labyrinthine corridors and innumerable bedrooms and bathrooms (none of which has ever been completely finished) and the four ‘tower’ rooms, one at each corner, projecting above the other roofs and affording wonderful views of the town, river and surrounding forest. It is to one of these towers – the one we call ‘the bookroom’ – that I have retreated to write this story.

When Uncle Umberto began to clear the land to lay the foundation for the third ‘shoe box’ (in the year of the great drought), he said one night he saw a light, like someone waving a flashlight, coming from one of the sandbanks that had appeared out of the much diminished river. Next morning he saw a small boy apparently stranded on the bank and he went down to the river, got into the corrial and paddled across. When he got close to the bank he realized that it was not a boy, but a naked old man, scarcely four feet tall, with a wispy beard and an enormous, crooked penis. This man gesticulated furiously to Uncle, indicating first that he should paddle closer to the sandbank and then, when the bow of the corrial had grated on the sand, that he should come no further. Uncle swears that the little man held him paralysed in the stern of the boat and spoke to him at length in a language he did not understand, although somehow he knew that the man was telling him not to build the extension to the house, because an Indian chief had been buried in that spot long ago.

My grandmother, who had lived the first fifteen years of her life aboard her father’s sloop and had seen everything there is to be seen along these coasts and rivers, did not believe in ghosts and walking spirits and she would have none of it when Uncle Umberto suggested they abandon the second extension to the house. To satisfy Uncle she allowed him to dig up the entire rectangle of land and when no bones were found, she said: ‘O.K. Umberto, you’ve had your fun, now get serious and build on the few rooms we need so your brother Leonard could marry the woman he living in sin with and move her in with the rest of the family. It’s more important to avoid giving offence to God than to worry about some old-time Indian chief who probably wasn’t even a Christian anyway.’

So Uncle built the shoe box despite his misgivings, but the day before his brother Leonard was to be married, there was an accident at the sawmill where he worked and a tumbling greenheart log jammed him onto the spinning blade and his body was cut in two just below the breastbone. Everyone agreed it was an accident, but Uncle Umberto knew why it had happened. Aunt Irene, Uncle Leonard’s bride, who was visibly pregnant at the time, moved into the new extension nevertheless and she and my big cousin Lennie have been part of the household ever since. Uncle Umberto, who never had children of his own, became like a father to Lennie and took special care of him, claiming that, from infancy, the boy had the identical crooked, oversized penis that the old man on the sandbank had flaunted. Uncle Umberto also saw from time to time in that part of the house, apparitions of both his brother Leonard and the Indian chief, the latter arrayed in plumed headdress and beaded loincloth and sitting awkwardly on the bed or on the edge of Aunt Irene’s mahogany bureau.

The others now living in the big house were my own family – Papi, Mami, my sister Mac, my two brothers and I – my uncle John, the lawyer, and his wife Aunt Monica, my uncle ’Phonso and the four children that my aunt Carmen had for four different men before she decided to get serious about life and move to the States, where she now works in a factory that builds aeroplanes and lives with an ex-monk who can’t stand children. My father’s other sister has also lived in the States from as far back as I can remember.

Actually, my Uncle ’Phonso doesn’t really live with us either – he is the youngest and, it is said, the most like his father, both in terms of his skill as a seaman and his restlessness and rebellious spirit. He took over the running of my grandmother’s sloop (which plies up and down the rivers, coasts and nearby islands, as it always has, engaged equally in a little trading and a little harmless smuggling), and always claimed he could never live under the same roof with ‘the old witch’ (his mother). So he spends most of his life on the sloop. On every long trip he takes a different female companion (‘...just to grieve me and to force me to spend all my time praying and burning candles for his wicked soul,’ my grandmother said). Once a year the sloop would be hauled up onto the river bank below our house for four or five weeks, so that Uncle Umberto could replace rotten planks and timbers and caulk and paint it. During this time Uncle ’Phonso would have his annual holiday in his section of the family home.

Uncle John, the lawyer, was the most serious of my father’s brothers – though he was not really a lawyer. From as long as I can remember he has worked in the district administrator’s office and has been ‘preparing’ to be a lawyer by wearing pin-striped shirts and conservative ties and dark suits and highly polished black shoes. His apprenticeship to the profession became an eternal dress rehearsal. Packages of books and papers would arrive for him from overseas (though less frequently in recent years) and we would all be impressed at this evidence of his scholarly intent, but as far as I know he has never sat an exam. He and Aunt Monica live very comfortably off his salary as a clerk in the district office, but they have agreed not to have any children until he is qualified. In the early years of their marriage the couple was cruelly teased about not having children. Papi would say, ‘Hey, Johnno, you sure is Monica Suarez you married, and not Rima Valenzuela?’ Rima Valenzuela was a beautiful and warm-hearted woman in town notorious for her childlessness. Since she was a teenager she has longed for children and tried to conceive with the aid of an ever-lengthening list of men (including, it was rumoured, one or two of my uncles). She was said to be close to forty now, and was beginning despairingly to accept what people had been telling her for years – that she was barren.

Every new-year’s day after mass people would say to Uncle John, ‘Well, Johnno, this is the year; don’t forget to invite me to the celebrations when they call you to the bar.’ But no one really believes any more that he will actually become a lawyer. One year Uncle ’Phonso patted him on the back and said consolingly, ‘Never mind, brother John, there’s a big sand bar two-three miles down river; I can take you there in the sloop any time you want, and you can tell all these idiots that you’ve been called to the bar, you didn’t like the look of it and you changed your mind.’

In a way, Aunt Monica was as strangely obsessive as Uncle John. Papi said it was because she had no children to occupy her and bring her to her senses. She seemed to dedicate her life to neatness and cleanliness, not only making sure that Uncle John’s lawyerly apparel was always impeccable, but every piece of cloth in their section of the house, from handkerchief to bed-sheet to window-blind, was more than regularly washed and – above all – ironed. Aunt Monica spent at least three or four hours every day making sure that every item of cloth she possessed was clean and smooth and shiny. She had ironing boards that folded out from the wall in each of the three rooms she and Uncle John occupied and kept urging the other branches of the family to install similar contraptions in their rooms. Once when my grandmother remarked: ‘All these children! The house beginning to feel crowded again. Umberto, we best think about adding on a few more rooms,’ Papi quipped: ‘Why? Just so that Monica could put in more fold-out ironing boards?’ – and everyone laughed.

* * *

One morning as we were all at the kitchen table, dressed for work and school and finishing breakfast, Uncle Umberto came into the room in his sleeping attire (short pants and an old singlet) looking restless and confused. We all looked at him, but before anyone could ask, he said: ‘You all, I didn’t sleep at all last night, because I was studying something funny that happened to me last evening.’ Everyone sensed one of his ghost stories coming and we waited expectantly. I had got up from the table to go and do some quick revision before leaving for school, but I stood my ground to listen.

‘Just as the sun was going down yesterday I went for my usual walk along the path overlooking the river – you know I does like to watch the sunset on the river and the small boats with people going home up-river from work in town. Suddenly, just as I reach that big rock overhanging the river at Mora Point, this white woman appear from nowhere on top the rock. Is like if she float up or fly up from the river and light on the rock. She was wearing a bright blue dress, shiny like one of them big blue butterflies...’

‘ Morpho,’ interrupted my brother Patrick, the know-it-all. And Papi also had to put in his little bit.

‘Shiny blue dress, eh? Take care is not Monica starch and press it for her.’ But they were both told to be quiet and let Uncle Umberto get on with his story.

‘She beckon me to come up on the rock, so I climb up and stand up there next to her and she start to ask me a whole set of questions – all kind of thing about age and occupation and how long I live in these parts and if I ever travel overseas – and she got a funny squarish black box or bag in her hand. Well, first of all, because she was white I expect her to talk foreign, like somebody from England or America, but she sound just like one of we.’ He paused and looked around. ‘Then after she had me talking for about ten or fifteen minutes, I venture to ask her about where she come from, but she laugh and say: “Oh, that’s not important, you’re the interesting subject under discussion here” – meaning me –’ and Uncle Umberto tapped his breastbone twice. ‘Then like she sensed that I start to feel a little uneasy, and she say: “Sorry, there’s no need to keep you any longer, you can continue your walk.” By then like she had me hypnotized, and I climb down from the rock onto the path and start walking away.’

‘Eh-eh, when I catch myself, two, three seconds later and look back, the woman done disappear! I hurry back up the rock and I can’t see her anywhere. I look up and down the path, I look down at the river, but no sign of her – just a big blue butterfly fluttering about the bushes on the cliff-side...’

It was vintage Umberto. Uncle John said: ‘Boy, you still got the gift – you does tell some real good ones.’

‘I swear to God,’ Umberto said, ‘I telling you exactly what happen. This isn’t no make-up story.’

Still musing about Uncle Umberto’s experience, we were all beginning to move off to resume our preparations for school and work, when Aunt Teresa began to speak in an uncharacteristically troubled voice.

‘Umberto, I don’t know who it is you see, or you think you see, but you got to be careful how you deal with strange women who want to ask a lot of questions – you say she had you hypnotized, well many a man end up losing his mind – not to mention his soul – over women like that. The day you decide to have anything personal to do with this woman, you better forget about me, because I ent having no dealings with devil women...’

This was certainly strange for Aunt Teresa, who usually shrugged off her husband’s idiosyncrasies and strange ‘experiences’ with a knowing smile and a wink at the rest of us. Aunt Teresa’s agitation seemed to be contagious among the women of the household. I noticed that Mami seemed suddenly very serious and, as Aunt Teresa continued to speak, Aunt Monica, preoccupied and fidgety, came and stood by the fridge next to me and began to unbutton my school shirt. As she reached the last button and began to pull the shirt-tails out of my pants, the talking stopped and everyone was looking at us.

Too shocked or uncertain to react to this divestiture before, I now smiled nervously and said: ‘Hey, Aunty, I’m not too sure what we’re supposed to be doing here, but should we be doing it in front of all these others?’

There was a general uproar of laughter and Aunt Monica removed her hands from my shirt as if stung; but she quickly recovered, gave me a swift slap on the cheek, and said, ‘Don’t fool around with me, boy, I could be your mother. Besides, everybody knows that I’m just taking off this crushed-up excuse for a school shirt to give it a quick press with the steam iron and see if I can’t get you to look a little more decent. If your mother can’t make sure you all children go to school looking presentable (and you, Mr. Nickie, are the worst of the lot), then somebody else will have to do it, for the sake of the good name of the family you represent...’ By the time she’d finished saying this, she was traipsing out of the kitchen waving my shirt behind her like a flag.

We did not realize it at the time, but Uncle Umberto’s story was the beginning of a strange sequence of events that was to befall him and to haunt the rest of us for a very long time.

No one was surprised when he revealed, a few days later, that he had met the woman again, and that she had walked up and down the riverside path with him, but the mystery of the woman was solved for me when she came into my classroom at school one day, along with our teacher, Mr. Fitzpatrick, who introduced her as Miss Pauline Vyfhuis, a graduate student who was doing fieldwork for her thesis in Applied Linguistics. She carried a tape-recorder in a black leather case and told us that Professor Rickford at the university had sent her up here to record the people’s speech for her research. When I went home and announced this to the family, they all accepted that Miss Vyfhuis must be Uncle Umberto’s blue butterfly lady – all except Uncle Umberto himself; he claimed to have spoken at length to his lady and she’d confirmed that she could appear and disappear at will; that she could fly or float in the air and that one day he (Uncle Umberto) would be able to accompany her – floating off the cliff to places unimagined by the rest of us.

‘Umberto, before you go floating off over the river,’ Papi interjected, ‘just make sure you take off them two four-wheel drives ’pon your feet, in case they weight you down and cause you to crash into the river and drown.’

Ignoring Papi, Uncle Umberto went on to tell us that, besides all he’d just said, he had also met Miss Vyfhuis, outside Arjune’s rumshop, and had even condescended to say a few words into her microphone. She was nothing like his butterfly lady; she was small and mousey-looking, and anyone could see that she could never fly. Also, her tape-recorder was twice the size of the magic black box carried by his lady... We shrugged – no one could take away one of Uncle’s prized fantasies.

A few months after this my grandmother died one night in her sleep. The family was not overwhelmed with grief; the old lady was eighty-nine years old, and although her death was unexpected, everyone said that it was a good thing that it was not preceded by a long or painful illness. ‘She herself would have chosen to go in that way,’ Mami said. Uncle Umberto seemed the one most deeply affected by the old lady’s passing; he seemed not so much grief-stricken as bewildered. It was as though the event had caught him at a particularly inconvenient time and for days he walked about the house and the streets mumbling and distracted. Uncle Umberto should have become the head of our household, and I suppose he was, in a way, but he seemed to abdicate all responsibility in favour of Aunt Teresa, his wife, who took on the role of making the big decisions and giving orders. Umberto’s slippers took their increasingly distracted occupant more and more frequently to the path above the river and he could be seen there not only in the evenings, but now also first thing in the morning and sometimes again in the heat of the day. None of us who saw him ever saw the butterfly woman – nor anyone else, for that matter – walking with him, although there were times when he seemed to be gesticulating to an invisible companion. Mostly he just walked. He haunted the riverside path like a Dutchman’s ghost and we all began to worry about him.

One evening not long after this, Uncle Umberto came home dishevelled and distraught, a wild look in his eyes.

‘She going,’ he said. ‘She say is time to go and she want me go with her.’

‘Go where?’ Aunt Teresa snapped. ‘Just look at yourself, Umberto, look at the state you have yourself in over this imaginary creature.’

‘I keep telling you,’ Umberto pleaded, ‘she’s not imaginary – I see her for true, swear-to-god, although it seem nobody else can see her. Now she say she going away, and I must go with her – or else follow her later.’

‘Tell her you will follow her, man Umberto,’ Papi said. ‘You know like how a husband or a wife does go off to America and then send later for the other partner and the children. Tell her to go and send for you when she ready. No need to throw yourself off the cliff behind her.’

I was sure Papi was joking, and there was a little nervous laughter in the room, but surprisingly, Umberto thought it was a great idea. His face cleared of its deep frown and he said simply: ‘Thank you, Ernesto, I will tell her that and see what she say,’ and he went off to his room, followed by his visibly uncomfortable wife.

Two days later Umberto reported that the lady had agreed to the plan; they had said their goodbyes early that morning and she floated off the rock where she had first appeared, and was enveloped in the mist above the river. Umberto seemed in very good spirits and the family breathed a collective sigh of relief. In the weeks immediately following he appeared to be his old self again – having a drink or two with the boys in Arjune’s rumshop, joking with the rest of us and talking of replacing the north roof of the house, which had begun to leak again. He never spoke of the butterfly lady.

In just over six weeks, however, Uncle Umberto was dead. He announced one morning that he was taking a walk into town to order galvanize, stepped into his famous slippers and disappeared down the road. It seemed like only minutes later (we hadn’t left for school yet) that we heard shouting outside and looked down the road to see Imtiaz, Mr. Wardle from the drug store and even old Lall at the forefront of a crowd of people running up the hill, waving and shouting. The only thing that we could make out in the hubbub was the word ‘Umberto’.

It seems Umberto had stopped at the edge of town to chat with a small group of friends when he suddenly looked up, shouted ‘Oh God! Child, Look out!’ and leapt right in front of one of the big quarry trucks that was speeding down the hill. He died where he had landed after the impact, his rib-cage and one arm badly smashed and his face cut above the left eye. The slippers were still on his feet. There was no child – nor anyone else – near to the truck.

Well, you can guess what everyone said: the butterfly woman appeared to him and led him to his death – just when we all thought he was rid of her. The family was devastated. Unlike my grandmother’s, Uncle Umberto’s funeral was an extremely sad and painful occasion – not least because we saw Umberto’s feet, for the first time ever, in a pair of highly polished black shoes. The shoes were large, but not as large as we thought they needed to be to contain Uncle’s feet. The thought that the people at the funeral parlour had mutilated his feet and crammed them into those shoes was too much to bear. We all wept, and scarcely anyone looked at Umberto’s face as he lay in the coffin – all eyes were on the extraordinary and deeply disturbing sight at its other end. At home, after the burial, we all turned on poor Aunt Teresa – how could she permit the undertakers to mutilate Uncle’s feet? My cousin Lennie, his favourite, said tearfully that not even God would recognize Uncle Umberto in those shoes.

‘You should have buried him in his slippers; those were his trademark.’

‘Trademark, yes,’ Aunt Teresa spat, her eyes bright with tears, ‘and they made him a laughing-stock – everybody always laughing and making fun of him and his big feet. I wanted that he could have in death the dignity he was never allowed in life, what with Ernesto and John and you and Nickie and the children always making cruel jokes about the feet and the slippers. God knows he used to encourage you all with his antics, it’s true, but it always hurt me to hear him ridiculed...’

At that point my brother Patti appeared in the room with the slippers in his hands, saying ‘These are fantastic, just amazing – nobody else in the world – just look at them!’ And he held them up, tears streaming down his face.

‘Give me those!’ Aunt Teresa shouted, flying into a rage, ‘He only been buried two hours and already you parading these ridiculous things and making fun of the dead. At least you could have a little respect for my feelings.’

As she snatched the slippers from Patti I couldn’t help noticing with awe that they still had the deep grooves of the tire tread and seemed to be hardly worn. At another time I might have remarked: ‘They look as though they have less than a hundred miles on them’ (that is, if Papi didn’t beat me to it), but now, with Aunty raging, we all kept silent and watched her disappear into her room, clutching the offending footwear.

* * *

You might think that the story is now ended, but in fact there is a little more to tell. You must remember that this is not the story of Uncle Umberto, but of his slippers. Several months later, when Aunt Teresa returned from a visit to her sister in Trinidad and seemed to be in a good mood, someone – Lennie, perhaps – casually asked her what had become of Uncle Umberto’s slippers. Her face clouded over, but only for an instant. She smiled and said: ‘Oh, those things – don’t worry, I didn’t burn them, only buried them away in the bottom of my trunk. I don’t think I’m ready to see them again yet,’ and the conversation moved on to other topics.

About a year later, when the house was in general upheaval – because Mr. Moses was replacing the rotten north roof at last; because Aunt Lina (one of my father’s sisters) was visiting from New Jersey and because my cousin Lennie had just disgraced us all by getting Rima Valenzuela pregnant (and him barely nineteen!) – Aunt Teresa came into the kitchen one night and announced that Uncle Umberto’s slippers had disappeared. ’What you mean “disappeared”, Aunty?’ Lennie said. ‘Remember you told us that you had put them in the bottom of your trunk?’

‘Yes,’ Aunt Teresa said, ‘in this big blue plastic bag; but when I was looking for them just now to show Lina, I find the bag empty. Look, you can still see the print of the truck tire where it press against the plastic for so long under the weight of the things in the trunk.’ And she held up the bag for us to see.

‘But it’s impossible for them to just disappear,’ Lennie insisted.

Aunt Teresa gave him a look: ‘Just like how it’s impossible for Rima Valenzuela to make baby, eh? You proud to admit that you responsible for that miracle, for all I know you may be to blame for this one as well.’

‘Ow, Auntie,’ I pleaded, ‘don’t start picking on him again.’ I was feeling for Lennie, who had taken a lot of flack from the women in the family (and had become something of an underground hero to the men and boys!).

‘OK. Look,’ Teresa said, ‘I don’t know who removed the slippers. I would have said it has to be one of you, but I always lock the trunk, as you know, and walk everywhere with the key – in this menagerie of a house that is the only way I can have a little privacy and be able to call my few possessions my own. The disappearance of the slippers is a real mystery to me, but you could go and search for yourself if you want.’ And she flung the bunch of keys at us, shaking her head. We did search – the trunk, the wardrobe, the chest of drawers, under the bed, everywhere, but there was no sign of the slippers. It was a mystery in truth.

Eventually the slippers became a dim memory for most of us. Life moved on; we children continued ‘to grow like weeds’, as my Aunt Monica would say. I went to board with cousins in the city during term-time, so that I could attend sixth form at college, and I found that my life changed, to the point where all that remained of Uncle Umberto and his slippers were memories, dim and fading memories. But.