Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

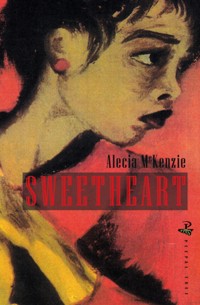

Shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Prize 2012. Dulcinea Evers, a young Jamaican artist who has reinvented herself in the USA as the flamboyant Cinea Verse, has died in unclear circumstances. But who was Dulcinea? Her friend, Cheryl, who is carrying her ashes back to New York from her Jamaican funeral, has one story, but the narratives of the other people in Dulci's life suggest that not even Cheryl's version is the whole one. In the words of Dulci's angry, disappointed father, her ineffectual mother, her middle-aged married lover and the angry wife who came after her with a machete, the art critic husband whom she used to get American residency, and Cheryl, the friend who has her own secrets, facets of Dulci begin to emerge: talented, reckless and, as we see when Aunt Mavis begins to speak, fundamentally alone. And it is Aunt Mavis, the solitary and reluctant seer, who understands the true challenge of Dulci's gift. In telling Dulci's story through those who speak to her, Alecia McKenzie has skilfully organised a narrative that is both multi-layered in offering deepening cycles of understanding, and has the onward thrust of progressive revelation. There is space, too, for readers to come to their own conclusions. Alecia McKenzie was born and grew up in Kingston, Jamaica. Her short stories, Satellite City, won the Commonwealth Writers regional prize for the best first work in 1993.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 206

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SWEETHEART

ALECIA MCKENZIE

FOR MY MOTHER

CHAPTER ONE

CHERYL

JamAir Flight 15

Cho, Dulci, why couldn’t you have been buried like everybody else? And why half of the ashes in Negril and half in New York? I just know these customs people are going to think it’s drugs I have in this bottle. The last time they stopped me it was because of you as well. Bring me some cerasee tea when you come to the gallery opening, you said, I need it to pep myself up because I’m not feeling too well these days at all. And although everybody warned me – “Don’t be a fool, girl; those customs people will embarrass you” – I still travelled with the cerasee. It was a chance to make up, to purge both you and myself of the bile of friendship gone wrong. But, of course, those customs people took one look at me and said: Open your bags. And there was the cerasee tea, right next to the Bombay mangoes your mother begged me to take you, and the hot peppers Aunt Mavis insisted on sending as a gift. Before I knew what was happening, they brought in their drooling dogs and their interrogation people. I tried to explain. Look, I said, it’s cerasee tea. You know, to wash you out, I mean, it’s a purifier, a de-toxer. They looked at me, eyes like stone. It cleanses your blood, I told them, makes you have, ah, bowel movements. I’m taking it to my friend. She’s not feeling well. Finally they called our embassy there in New York and someone came to verify that yes, it was cerasee tea and perfectly legal at home. They let me go but kept the tea, the mangoes and the peppers, saying I wasn’t allowed to bring in farm produce, didn’t I know that? When I told you about my ordeal, you laughed and rolled me a fat spliff, the first I’d ever had in my life. You coughed almost non-stop as we smoked it, a deep racking sound that seemed to come from the bottom of your chest. I knew you needed to see a doctor, but you waved away my concern and questions.

I wonder what the customs people are going to make of this Red Stripe Beer bottle now? I really wish I had a nicer container but this morning, just before I left Kingston, the damn urn slipped out of my hands and crashed to the floor, right in the middle of Norman Manley International Airport. And I’d been holding it so carefully. When he saw my tears, a lanky guy dressed in a blue baseball cap and loud white basketball shoes, offered to run upstairs to the airport canteen and fetch an empty bottle. I nodded without speaking and, when he came back, he got down on his knees beside me and helped to pinch up the ashes; we got most of it into the beer bottle. If we hadn’t, people would’ve tramped through your remains – at least this half of them.

Through it all, I could hear you laughing.

So now I am on the plane, with three-and-a-half hours to go before we land at JFK, and I don’t know whether this is bad luck or good fortune, but the man who helped me earlier is sitting in the same row as I am. He has an aisle seat, I am at the window, and the seat between us is empty: thank goodness for the space. He has a sweet, low voice that contrasts with the youthful clothes. I look him over and he turns to smile at me. I now notice the thick gold chain around his neck, with the outsized cross at the end, and I try to keep my eyebrows from going up. You always used to say, Dulci, that I was wrong to judge people by how they looked, but that’s because you yourself were partial to loads of gold jewellery. Wearing tons of cheap-looking cling-clang gives a certain impression, you have to admit. Still, for all I know, this guy could be a cardinal and not a dancehall star.

He wants to talk, the last thing I feel like doing.

“So, who died?” he asks, gesturing towards the beer bottle, which I have tucked into the seat pocket alongside the safety-precautions card and the SkyWritings magazine.

“A good friend of mine.”

“Sorry to hear that.”

I look through the plane window at nothing and hope he’ll get the hint that I’d rather be left alone.

“What killed him, or her?”

“Her. Cancer.”

“Oh, a lot of people getting that now. Must be something in our food.”

“Yes.”

He reaches for the in-flight magazine, flicks rapidly through it and puts it back. The action reminds me of you. “Reading gives me a headache,” you used to say. And right up to the end, except when the pain became too vicious, you had the clear beautiful eyes of someone who’d never read a book all the way through.

I turn again to look at the man beside me and he turns at the same time. His eyes are such a deep brown, and soft. He smiles disarmingly, and I feel like crying again. What is wrong with me!

“My grandmother died from cancer last year,” he says. “The sickness drew her down to nothing. Pure skin and bones at the end.”

“Yes, that’s what it does to you.”

“She raised me when my mother went abroad to work. Used to give me some big licks when I didn’t do what she wanted. I never ever think I would see her like that.”

“I hope she didn’t suffer too much,” I say, feeling my chest tighten. Skin and bones, that’s what you were, too, Dulci. As light as a child.

“In three months she was gone. I was in New York doing some business, but I dropped everything and went home. I was with her at the end, and that’s something I’m glad for. What about your friend? She used to live in New York?”

“Yes. And I was there at the end, too. But it’s not something I can say I’m happy about. Anyway, the funeral was in Kingston. She just made me promise before she died that I’d take some of the ashes back to Manhattan.”

“Mind the customs people, though. They might think you have chemical or biological weapon. That’s all they can think ’bout now.”

I laugh out loud, and he laughs along.

“By the way, what’s your name?” I ask him.

“Danny,” he smiles, and the openness of his face makes me catch my breath. You would like him, Dulci. If you were here in the flesh, I’m sure you would invite him to your apartment the minute the plane begins its descent.

“Mine is Cheryl.”

“You know, Cheryl,” he says, with an infectious grin. “When I saw you in the airport, I said to myself: I hope I get to sit beside that beautiful lady. So now I can’t believe me luck.”

Oh good Lord, what next? I’m sure you would have played along with him, Dulci, but I’m not in the mood.

“Danny, that’s so sweet. Listen, I have a bit of a headache, so I’m going to take a nap, okay?” I inhale deeply, recline my seat and turn my face to the sky, eyes closed, remembering.

You moved into our neighbourhood when you were thirteen, Dulci. Do you remember how I laughed when I heard your father calling you by your full name, “Dulcinea Gertrude Evers”?

“Is where you get that name from?” I asked. And you kissed your teeth and didn’t answer. Always feisty, that was you. Never bothered to waste your time answering unpleasant questions. I eventually found out that your father had named you after some character in a book by some long-dead writer. And you didn’t appreciate it. Years later, when you landed in New York, you quickly rechristened yourself “Cinea Verse” and signed all your work with this name. It was memorable, in a way Dulci wasn’t.

Your father, though, couldn’t understand why you weren’t proud to be Dulcinea Gertrude Evers. “Too full of herself for her own good,” I overheard him telling your mother once. “If she would pay more attention to her lessons, she’d do better.” And your mother smiled in her vague, distant way.

Your father was always a funny man, Dulci; it’s something everyone knew right from the moment he set foot in Meadowvale. The way he turned your three-bedroom house into a semi-mansion had the whole neighbourhood talking, and people from other streets would come over to Hibiscus Drive just to walk past your house and gawk at the turrets and balconies. Your father must have been a king in a previous life, but he still didn’t like you acting the princess – which came so naturally to you.

He always wanted more from you, wanted you to like the books and the music he loved so much. Do you remember the songs he taught us to play on the piano – “Jamaica Farewell”, “Yellow Bird” and “Brown Girl in the Ring”? I was a quick learner, but you weren’t, and your father would shout at you when you got a note wrong, his harsh bark belying his slight form. Meanwhile, your mother made sure she stayed out of the way of this short, wiry man who couldn’t tolerate stupidity, as he was so fond of saying.

Everybody in the neighbourhood agreed that if you had inherited your father’s feistiness and pride, you’d also been blessed with your mother’s good looks: the flawless honey-coloured skin, the wavy hair, the big almond-shaped eyes. Mrs. Evers was still beautiful after having you and your five brothers, and she probably could easily have ditched your father and got herself a man who respected her, that is, if her mind had been in the right place. But your mother wasn’t all there, was she, Dulci? The elevator just didn’t go all the way to the top, as my Aunt Mavis used to mutter from time to time.

“So, sweetheart,” your mother would say to me, “I hear that your Granny lives in England?”

“Yes,” I would answer. “She left when I was a baby.”

“And does she like Canada?”

“She’s in England.”

“Oh, yes. England. Do you want some lemonade?”

“Yes, thank you, Mrs. Evers.”

“Does your Granny come home from America sometimes?”

And the questioning would go on, a different country each time, and the lemonade forgotten. It irritated everyone, most of all your father.

“Shut up, woman,” he would shout from somewhere in the house. “You too damn stupid.” But your mother never seemed to mind. She just smiled, her big eyes vacant.

As she often forgot people’s names, your mother called everyone “sweetheart”, including you, but she said it in a special way for her “one and only” daughter. “Sweetheart, your friend is here to see you.” “Sweetheart, don’t stay at your friend’s house too long. Her mother has things to do.”

“My aunt,” I corrected her, for the millionth time.

When your father discovered that I was a student at Omega Academy, he went personally to the headmistress, Sister Marie, to beg her to let you in as well. He thought that changing schools might improve your grades, and your attitude. Well, the teachers tried, but the only “A” you ever got was in Art, not only because you could draw things seen and unseen, but because, let’s face it, Mr. Walcott liked you. You never really had a head or a yen for studying.

Throughout the years at Omega, your father always screamed when he saw your report card, and he would go on for days about how good my grades were, but you eventually learned to stop crying and ignore him. Besides, you were the prettiest girl in our class. Who needs good grades when you’re beautiful? Mr. Evers must have been around long enough to know this, but he foolishly believed brightness was more important than beauty.

Even on Sports Day, when he should’ve been the proudest parent, he still managed to be disappointed. “Well, she can run, but can she add two plus two?” was all he would say when you came first or second on the track. By then you had started referring to your father as “The Fool”.

“Who cares what The Fool thinks?” you would shrug, after another put-down.

At Omega, you also played ping-pong and netball, and everybody wanted you on their team. You made it all look so easy, never seemed to sweat. Before we became friends, I’d never liked sports because I only had to get on the netball court for people to collapse in laughter at my clumsiness. “Just ignore them and enjoy yourself” was your advice. It’s a lesson I still haven’t learned fully.

I always envied your ability to take it easy, Dulci, to let gossip and bad luck run off you like rain off a banana leaf. When it came time for “O” levels, I swotted for nights in a row, while you said what will be will be, and went about your usual business – beach, movies and parties. I passed nine subjects, which ensured my place at university. You passed math, much to your surprise, and failed everything else, including art. You tried not to show it, but I knew that failing art must have upset you because it was the one thing you had felt sure of. A couple of months later, you started working at JamCom Bank and I headed off to UWI, but we saw each other on weekends. You came often to our student parties, and I would introduce you round. Not that you needed much introduction. Guys on campus were attracted to you like flies to curry-goat.

The air hostesses are serving food. Danny gently taps my shoulder and asks if I would like something to eat. I shake my head “no”. I’ve stopped eating on planes because the turbulence always starts as soon as I take a bite of the mush. Danny tucks into the unidentifiable substance – the hostess said it was an omelette – on his rectangular piece of white plastic, and I admire his appetite.

He glances at me. “It not too bad,” he says. “You should have some.”

“I’m not hungry.”

When he’s done, he gazes at the beer bottle in the seat pocket. “I could do with a Red Stripe, but I guess it’s too early for that.”

I nod, thinking that I could do with something much stronger than a Red Stripe. A rum punch, for instance, with more rum than punch, even if I’ve never really liked the taste.

“Did your friend like beer?” he asks, looking again at the bottle.

“Yes. And lots of other things.”

“She was how old?”

“Thirty-four.”

“Wow! That’s two years younger than me.”

“Yes. She was ready to go, though, by the end.”

I’ll have to keep believing that, Dulci. That you were ready. You said you were, and even if you had changed your mind in the last moments, it was too late. You made me promise: whatever happens, don’t back out. I had to keep the promise, right? I mean you had done so much for me, in so many ways. It was the least I could do.

I thought of all this during the funeral service, hoping that somehow I’d be forgiven. Seeing your father cry really got to me. And Aunt Mavis! I never knew she had tears. The woman put down one piece o’ bawling. Everyone was shocked. Where did all that water come from in her dry, thin body?

But she always did like you, and her face used to break out into one of those rare smiles every time you walked through the gate and stepped onto our verandah. You’d been so curious about her when you moved into our neighbourhood, this woman who hardly spoke.

“Your mother is really kind, but why she act so strange?” you asked.

I explained that Aunt Mavis wasn’t my mother, although she looked like me. She was my mother’s sister. My mother died before I turned two, and I don’t remember anything about her. I knew her only from old discoloured Polaroid photographs. In one, she’s standing in front of a picket fence and wearing a long wide-skirted floral dress, her hair pulled back in a bun. Tall and slim, she has a serious but touchingly sweet face. Aunt Mavis looked very much like her, except that the sweetness had long oozed out of her pores.

“And is Trev your brother or your cousin?” you inquired. “The two of you could almost be twins.” I didn’t know how to answer, but I told you the story anyway, the first person I’d told it to, and you listened without comment.

After my mother died, Aunt Mavis and her son Trevor came to live with my father and me. Auntie never mentioned Trev’s father, and Trev never asked about him, at least not when I was around. Trev was one year older than I, and we shared a room until I was about ten. Then my father added on a fourth bedroom so that each of us in the house could have our own room. Aunt Mavis was never still for a moment, she was always working – sweeping the floor, washing clothes, cooking. And she barely spoke to me, Trev or my father. She had eight words a day: yes, no, come eat, go to your bed. She never treated me any differently from Trev; we got equal-sized portions of tongue-burning food and the same responses to our questions.

Trev and I grew tough on Aunt Mavis’ cooking. Everything was peppered and we had to learn how to eat it or go hungry because my father was a pepper-man and Aunt Mavis didn’t see the need to prepare two separate pots. At dinner time, Trev and I ate with tears streaming down our faces and loud sniffles as the pepper took its toll. Daddy fed us huge amounts of Buckingham ice cream after each meal. Later we learned to eat freshly cut hot peppers without a single grimace and, when we made new friends, our favourite trick was to see how much pepper they could eat without running home bawling. (You passed the test with flying colours, Dulci.)

Aunt Mavis lived in a cloud we couldn’t penetrate, and my father, while he spoiled us with toys and treats, was also distant. He worked such long hours as an accountant at Mutual Building Society that we were lucky if we saw him two hours daily during the week. Aunt Mavis called my father “Mr. Francis” to his face and “That Man” behind his back, and he called her “Miss Mavis”. Every weekend he gave her housekeeping money in a small brown envelope with her name written on it.

We knew that my father had women friends because he went out every Saturday night and some nights he didn’t come home until the morning. But we never heard anything about the women until he started seeing a barrister named Gloria Armstrong who had built a humongous house up on Jack’s Hill, with money she had borrowed from Mutual. People who knew of the house always talked about the Roman columns. And there were whispers everywhere that my father was going to marry this rich woman, whose cousin was the Minister of National Security or something like that.

Gloria Armstrong was famous for making criminals walk free. That’s what people said. “If you kill somebody, just go see Gloria Armstrong. She’ll get you off scotch-free.”

One Friday evening, my father announced calmly that we would have a special guest to dinner on Sunday, his friend Gloria, whom Trev and I were to call “Auntie Gloria”. He asked Aunt Mavis to hold back the pepper because Auntie Gloria didn’t like hot food. Aunt Mavis said sourly, “Yes, sah. Is you paying for it, sah.”

On Sunday morning, my father plaited my hair himself. I never knew he could plait hair. It was strange feeling his big hands turning the strands of hair and tying in a ribbon. He was gentle, unlike Aunt Mavis. Then he told me to put on my prettiest dress. I choose a blue-and-white striped outfit that Aunt Mavis had bought me, and Trev put on black pants and a white shirt. Aunt Mavis kept on her house dress, an unbecoming grey bag.

Gloria Armstrong arrived at 12:30, in her shiny green Volvo. She was a tall, bony, light-skinned woman with bobbed black hair, but she had a kind face and laughed a lot when we were introduced. Every time she laughed we stared at her teeth – they would have made a rabbit proud. “You ever see buck teeth like that?” Trev whispered to me. I shook my head, mute.

Auntie Gloria had brought us presents: for me a white doll that could close its blue eyes, and a cowboy hat for Trev. I hadn’t played with dolls in years, and I couldn’t see Trev wearing that hat; he would have been laughed out of the neighbourhood. We said, “Thank you very much, Auntie Gloria.”

The lunch was rice and peas, chicken with fried plantains, and a lettuce and tomato salad. It had no taste. Aunt Mavis had not only held back the pepper, but also the salt, thyme, garlic and onions. While Daddy, Auntie Gloria, Trev and I ate in the dining room, Aunt Mavis sat outside on the verandah, talking to herself.

“Lord, it look like it goin’ rain and I have so much clothes to hang out. What I goin’ do wid dem, eh?”

Inside, Trev and I tried to eat the food but could manage only a few forkfuls. My father and Auntie Gloria ate heartily and, when the lunch was done, they told us they were going to take us for a ride to Hellshire Beach, although we wouldn’t be able to swim since we had just eaten. Trev and I changed into shorts and tee-shirts and excitedly piled into Auntie Gloria’s Volvo, waving to Aunt Mavis who kept her eyes on the ground and didn’t wave back.

At Hellshire, Daddy told us the news. He and Gloria were planning to get married, but she wasn’t going to come and live with us; he and I were going to live at her house.

“And Trev and Aunt Mavis?” I asked, while Trev hung his head, his chin seemingly glued to his chest. Daddy said I could visit them on weekends but that they would stay in Meadowvale because things were more “convenient” that way. I flew into a childish rage and said I wasn’t going anywhere if Trev and Aunt Mavis couldn’t come too. My father’s face tightened and, for a brief moment, I thought he would hit me, but then Auntie Gloria laughed and said, “Let the child do what she wants, Francis. Children know their own minds these days.”

Daddy stared at me, then at Trev, and I swear I’d never seen such a look of dislike on anyone’s face. Trev didn’t meet his gaze, and my father finally turned his eyes to the sea.

“Millstone round me neck,” he said to no one.

When we got back home, the verandah was covered with broken plates, and Aunt Mavis was nowhere to be seen. We found her at the back of the house, in the laundry room, scrubbing the clothes as if she were trying to get out banana stains.

Wordlessly, my father cleaned up the mess on the verandah before leaving with Gloria. He told Trev and me he would be back the following night.

Within two months, my father had moved into the mansion on Jack’s Hill, and I stayed on with Aunt Mavis and Trev.

When I’d finished telling you the story, Dulci, you said: “Well, I’m glad you living here in Meadowvale and not on Jack’s Hill. But next time you go to visit you father and Gloria Armstrong, can I come? That house sound like something else.”

I said: “Of course, no problem. You can come with me any time, as long as you give me one of your puppies.” Your father had bought a trio of mixed-breed dogs to protect his castle, and one of them had just had puppies. You laughed and promised to see what you could do.

A few days later, you brought me my first pet. He had fluffy beige hair and light brown eyes, and he constantly wanted to play. Both Trev and I fell in love with him right away. We named him “Pepper” and were surprised at how much Aunt Mavis took to him. She made sure he always had food and water, and she even went to the pharmacy to stock up on de-worming medicine. Pepper rapidly became the most important part of the family.

As Pepper grew bigger, Aunt Mavis got into the habit of carrying on long monologues with him.

“But, Pepper, what I goin’ cook this evening, eh? What you think ’bout ackee and salt fish with green bananas and some fry-plantains? That no sound good?”

And when Trev said, “That sound good, Mama” she ignored him. We hung around Pepper to find out what we would have for dinner, which people Aunt Mavis couldn’t stand, and what my father had been up to.

“But Pepper, you see how man fool-fool? That woman must be telling him not to come look for his pickney. Is weeks now him don’t show up. Not that we miss him at all.”