Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

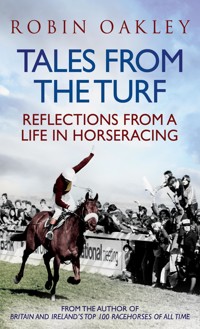

Britain and Ireland's Top 100 Racehorses of All Time author Robin Oakley takes us on a canter through the colourful world of horseracing. Join him as he shares evocative personal stories of being there at racing legends' key moments, such as Frankie Dettori riding seven winners in a day at Ascot. He debates whether jockeys are sportsmen or masochists – jump jockeys can expect a fall on average every 13 rides – and reminisces about unusual achievements, including trainer Sirrell Griffith's Cheltenham Gold Cup win after milking his 100 cows that morning. Tales From the Turf is an extraordinary account from the Spectator's long-running Turf columnist, and a man for whom horseracing is a lifetime's passion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Printed edition published in the UK in 2013 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.net

This electronic edition published in 2013

by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-190685-067-8 (ePub format)

Text copyright © 2013 Robin Oakley

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

To Carolyn, who has always indulged my passion for racing despite not sharing it – the greatest gift a lifelong lover can give.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robin Oakley was European Political Editor at CNN International and before that Political Editor of the BBC and of The Times. The author of numerous books on horseracing, he has been the Spectator’s Turf correspondent for almost twenty years. His most recent book is Britain and Ireland’s Top 100 Racehorses of All Time, published in 2012 by Icon Books.

CONTENTS

Title page

Copyright information

Dedication

About the author

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A Zambian beginning

Hurst Park memories

Liverpool days

Grand National

Epsom days

The Derby

Cheltenham

Martin Pipe

Nicky Henderson

Races and courses

Kempton Park on Boxing Day – King George Day

Glorious Goodwood

Monday nights at Windsor

Ascot and the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes

Doncaster and the St Leger

Sandown’s Coral-Eclipse

Newmarket

Brighton

Jockeyship

Are jockeys masochists?

Don’t marry a jockey

Dean Gallagher

Kieren Fallon

Trainers

Lambourn

Clive Brittain

Barry Hills

Paul Nicholls

Horses

Mandarin

Russian Rhythm

Frankel

Rainbow View

Denman

Singspiel

Betting

Ownership

Racing abroad

New Zealand

France

Hong Kong

Cyprus

Dubai

Mauritius

Racing issues

The all-weather

The whip controversy

Women jockeys

Too much racing?

Index

First plate section

Second plate section

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Images courtesy of the Press Association unless otherwise stated.

First plate section

Hurst Park when it was still a racecourse.

‘Prince Monolulu’.

Sea The Stars and Michael Kinane triumph in the Derby.

Marcus Tregoning’s Sir Percy taking the Derby from Dragon Dancer and Dylan Thomas.

Galileo: a top-class Derby winner.

Persian War winning his third Champion Hurdle in 1970.

Henrietta Knight with Best Mate.

The fairytale turrets of Goodwood.

Racegoers arriving at Windsor by boat. (racingpost.com/photos)

Ladies Day at Aintree.

Kempton, 1996: One Man heads for victory in the King George VI Chase.

Ouija Board takes the Nassau at Goodwood from Alexander Goldrun.

Giant’s Causeway beats Kalanisi in the Coral-Eclipse.

Sir Michael Stoute on the receiving end of a smacker from Frankie Dettori following their St Leger win in 2008.

Second plate section

Richard Hughes.

Kieren Fallon.

Frankie Dettori.

Bookmaker Gary Wiltshire.

Tony McCoy.

Nicky Henderson’s horses on the gallops at Seven Barrows.

Nicky Henderson at Seven Barrows with Gold Cup winner Long Run.

Trainer Barry Hills with 2,000 Guineas winner Haafhd, led up by Snowy Outen.

Henry Cecil supervising the morning routine. (racingpost.com/photos)

Paul Nicholls with Kauto Star and Denman.

Russian Rhythm winning the Lockinge Stakes with Kieren Fallon.

Mandarin poised in second to overtake Fortria and win his Cheltenham Gold Cup in 1962.

Singspiel at the Breeders’ Cup: a tragic end to an illustrious globe-trotting career. (Getty images)

Sha Tin, Hong Kong. (Getty images)

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum.

World Cup day in Dubai.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to all the trainers and their wives, husbands, partners and staff who have allowed me into their yards over the years to share the magical world that training racehorses can be. Thanks too to the jockeys who have nipped out of the weighing room on busy afternoons to spare me a few minutes giving me their version of special moments on the track.

Thanks especially to the late and much-missed Frank Johnson who as editor of the Spectator brought me back into writing about racing when I had for too long been spending all my time with politicians, the people who tell lies to journalists and then believe what they read. Thanks also to all those Spectator readers who wrote in to protest after editor Boris Johnson dropped my Turf column to create more room for politics – and to Boris for then having the grace to reinstate me. Thanks to the Spectator’s understanding Arts Editor Liz Anderson and to the Financial Times for allowing me to recycle some of the material which has previously appeared in their publications, and to Racing Post Books for allowing me to reuse material first acquired in writing for them my biographies of Barry Hills and Clive Brittain. A very big thank you also to Peter Pugh and Duncan Heath of Icon Books for conceiving this volume of racing experiences and encouraging me to write it. I am grateful also to my friend Derek Sinclair for his good fellowship on the racecourse, even if he does have an irritating habit of backing far more winners than I do. And as always the deepest thanks of all to my long-suffering wife Carolyn who has spent a lifetime putting up with me and the havoc caused in our social life by my deadlines.

INTRODUCTION

You have to be there. With the BBC having chickened out of racing, Channel Four’s team deliver well-informed and colourful coverage. But horseracing needs a broader canvas than the 28in screen. Even with a plate of tongue sandwiches, a ready supply of Budweisers from the fridge and the form book and telephone to hand, racing on TV can never quite compensate for not being present. You miss the buzz around the betting ring, the soft thud of hooves on wet turf, the instinctive intake of breath as a champion surges away from his field, the exhilaration of an air-punching jockey and his mount swaggering into the winner’s enclosure. Racing has to be heard, smelled and absorbed as well as watched. And with a fiver on the nose you can even, for a moment, feel a sense of temporary ownership as your selection flashes first by the post.

That fine Australian writer Les Carlyon put it best in True Grit. Scoffing at the description of racing as an ‘industry’ he declared, ‘So is packaging and tens of thousands don’t stand around cheering a cardboard box that happens to be rather better than the other cardboard boxes.’ Racing, he said, is ‘an addiction, a romantic quest, a culture and a certain sense of humour. It is loaded with dangers, physical and financial and comes with a hint of conspiracy. In other words, racing is interesting.’

Buying a boat has been described as like standing under a shower and shredding £10 notes. Pessimists would tell you that racehorse ownership is like standing in a heap of stable manure burning twenties. The trainer of a horse in which I had a share told our jockey one day in the parade ring to ‘Let him find himself’. ‘Oh please,’ I implored, ‘Couldn’t he just for once find the other horses in the race?’

But, win or lose, there is for me no sport with the same appeal. Jockey Mick Fitzgerald famously responded to interviewer Desmond Lynam’s ‘How did it feel?’ inquiry after he had ridden Rough Quest to win the Grand National that it was ‘better than sex’, getting himself in trouble with his lady at the time, who apparently complained that he had rarely given her enjoyment for more than the nine minutes 45 seconds an Aintree winner can be expected to take to complete the race.

If Mick was overdoing it just a tad I would still go along with his fellow jockey who described going racing as ‘the best fun you can have with your clothes on’. Racing is about speed, spectacle and athleticism. It is about colour, courage and character, about passion and the pursuit of perfection. For spectators it is simple: who passes the post first. To enjoy it you don’t have to master the intricacies of rucks and mauls, the offside trap or when to take the new ball. It is the most instantly sociable sport of all. Your companion or client doesn’t have to shut up for 90 minutes while the game is played; instead it is ‘How did yours do in the last? What do you fancy for the next?’

Racing changes people’s character: the tightest of bank managers splashes out on champagne after a win, the most decorous of ladies raises her hemline six inches or risks a crazy hat. No sport’s appeal spans the classes better. Duchess and dustman unite in cheering home a winner.

The sheer beauty of the participants is enthralling. Watch the early summer sun glinting off the flanks of a perfectly toned Sea The Stars or the grace and power of Kauto Star taking a Gold Cup fence in his prime and you have no need of a picture gallery. As Clive Brittain’s owner Lady Beaverbrook once said, ‘I have all the art I need but nothing makes my heart beat like a horse.’

Racing also appeals to that other basic instinct, the human love of a flutter. It carries a beguiling whiff of risk and uncertainty.

There was the famous story of the Dubliner at the Cheltenham Festival who won enough on Ireland’s champion hurdler Istabraq to redeem his mortgage. He then lost the lot on Ireland’s failing hope for the Gold Cup, only to retort, ‘To be sure, it was only a small house anyway.’

Racing people are good to be with because they are optimists. The veteran US trainer Jim Ryan once declared that no man ever committed suicide or thought of retiring while he had a good two-year-old in his barn for the season ahead. The sport is full of character. Compare today’s monosyllabic footballers with jockey Jack Leach, author of the marvellously titled autobiography Sods I Have Cut on the Turf. He spent his nights in the Turkish baths in Jermyn Street to keep to his riding weight: ‘I used to take off ¾lb extra so that at the racecourse I could have a small sandwich and a glass of champagne before racing started. It made me feel a new man. If I had a few ounces to spare the new man got a glass too.’

Jack Leach was a Flat jockey. To me the jumping riders have an extra dimension: it is hard to underestimate the sheer courage it takes to drive half a ton of horse across a series of obstacles in cold, wet and biting wind for no more than £158 a time when they know that statistically they can expect a fall from every thirteen rides. When he quit the saddle to train, Brendan Powell reflected, ‘Over the years I’ve been pretty lucky with injury.’ There’s lucky and lucky: he had endured two broken legs, two broken wrists, both collarbones shattered by repeated breaks and a ruptured stomach.

To me racing’s appeal has much to do also with the bond between the rider in the saddle and the animal beneath. Jockeys need a clock in their head, sensitive hands and physical strength. But horses are individuals. Some like to force the pace in front, others are happier coming from behind. Some shrink from contact or stop the moment they have their head in front. Yet jockeys must divine their partner’s character within minutes of meeting. Some have met their mounts on the gallops; often they have only the time from mounting in the parade ring to when the stalls open to get to know each other. The horse does not know how far away the winning post is and in that time a bond of trust must be established.

Frankie Dettori claims that within seconds of sitting on a horse he can divine its character, even its best distance. If ever I envied someone a gift that is it.

I was useless in the saddle, worse than a sack of potatoes, but that has never curbed my enjoyment from being with racing people. It is a little like the experience of the Parachute Regiment commander who was asked at his retirement party what it was that he enjoyed about jumping out of aeroplanes. ‘I hate jumping out of aeroplanes,’ he said. ‘It makes me sick to the stomach every time I do it. But I just love being with the kind of people who do like jumping out of aeroplanes.’

For me too there is no place like the racecourse. I love being with racing people, who embrace all types, from royalty to the clergy. Though I have to admit there are some who don’t share my pleasure. I was once at a Gimcrack racing dinner in York where a distinguished clergyman was invited to say grace. ‘I won’t, if you don’t mind,’ he replied. ‘I would rather not draw the Almighty’s attention to my presence here.’ I’ve always been ready to take that risk.

A Zambian beginning

An early humiliation might have put me off horses for good. My father was a civil engineer and we lived from 1948 to 1951 in what was then Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) while he was engaged in projects like Livingstone Airport and the Kafue Bridge. We almost led the colonial-style life and my mother had a horse, Pedro, a rangy chestnut with a white blaze. Although he was compliant with those of the female gender, the bad-tempered Pedro’s main pleasure in life seemed to be attempting to maim with hooves or teeth any male human who came in contact with him. He was stabled close to what passed for the local racecourse in Lusaka, which is where, after a few lessons, I used to try to ride him.

Facing away from the stables, Pedro would not go a yard without maximum human effort. Turn his face for home, however, and he would become a tearaway enthusiast determined each time to break any Lusaka record for five furlongs. Naturally the first time he did it to me I came off. As I slowly sat up counting my bruises, an assured young lady of eleven or twelve rode up, leading another horse alongside hers. In total control she collected a self-satisfied looking Pedro (I swear he was as close to smirking as a horse can get) and inquired solicitously, ‘Are you all right? Can I help you?’ She was kindness personified but for a self-conscious ten-year-old boy there could be no greater humiliation.

Hurst Park memories

We returned from Africa to live in East Molesey, Surrey, a stone’s throw away from the old Hurst Park racecourse – well, if you had a smallish stone and a particularly good throwing arm. Sadly back in 1962 Hurst Park became a Wates housing estate but before then it had hooked me finally and irrevocably into racing. I used to ride my bike down the road, prop it against the fence and stand on the saddle or climb a tree as the jockeys rode by. There would first be the thunder of approaching hooves, then the blaze of multi-coloured silks as the riders flashed past: the likes of Gordon Richards, Eph Smith, Scobie Breasley, Charlie Smirke and Manny Mercer shouting at each other for room or cursing whoever was holding them in on the rail. They would disappear in a creak of leather and smacking of whips, the lighter divots they had kicked up floating back to earth behind them, to be greeted half a minute later by the roar of sound from the crowds in the stands as they fought out the finish.

Sometimes I would walk round to the entrance before racing, to watch the ‘Find the Lady’ three-card tricksters plying their trade on upturned orange boxes, one man warily on the watch for approaching constabulary as the other made his pitch. Equally cautious was a character they called the ‘Watchman’ who would open his coat to reveal 20 or 30 dangling timepieces available at bargain prices. Sometimes tipster Prince Monolulu would be there in his fake African Ostrich-feather plumes rasping out his familiar cry of ‘I gotta horse’, encouraging punters to part with a few shillings for a little slip of paper. The tips were mostly rubbish, I heard punters grumble, but he deserved the cash for his entertainment value as he told the crowds:

God made the bees

The bees make the honey

You make a bet

And the bookies take your money.

Peter Carl Mackay, Monolulu’s real name, wasn’t any kind of prince in fact, although it didn’t stop him from strolling nonchalantly among the royals at King George VI’s funeral. Apparently Jeffrey Bernard, a fellow Spectator columnist, claimed that he was personally responsible for Monolulu’s demise. He visited the ailing tipster in hospital and gave him a box of chocolates. Monolulu chose a strawberry cream and promptly choked to death. There have to be better ways to go.

Once or twice at Hurst Park, after three or four races had gone, a friendly gateman would let me slip in for nothing, and from the start the subtle chemistry of the racing scene had me entranced. It was that extraordinary blend of the upright and the raffish, the social mix of shirts-off punters in the jellied eels inner ring peeling fivers off back-pocket wads, raucous bookies shouting the odds and elegant owners’ wives in parade-ring silk dresses.

Hurst Park being a jumping course as well as a Flat racing venue, you would see both the emaciated white-faced pros from top yards and the pink-cheeked farmers’ sons hoping to steal a novice chase on the family’s pride and joy. Curly-haired young trainers in cavalry twills and velvet-collared coats blowing Aunt Honoria’s patrimony in a couple of experimental seasons would mingle with weary-eyed ex-jockeys trying to make a go of it with a handful of cast-offs in a dilapidated yard.

Sometimes I would get a different view of the racing. Down by the seven-furlong start at the end of the straight, between the racecourse and the river Thames, was the ‘Upper Deck’ swimming pool. On the raised section which gave the venue its name you had the perfect view of the riders jostling at the tapes before the off, and more than once a jockey with a roving eye for the bikini-clad lovelies calling down to him would miss the break.

With nothing else left of old Hurst Park it is at least a consoling thought that when it died twenty acres of prime Thameside turf went into the laying of Ascot’s new jumping track.

Liverpool days

The first opportunity I had to mix with and write about racing people came when I left Oxford and joined the Liverpool Daily Post as a graduate trainee. It was just after the Beatles had moved on from Merseyside to worldwide adulation and a friend insists he remembers a conversation one day which went:

Friend: ‘Are you coming to the Iron Door this week to hear the Rolling Stones?’

Oakley: ‘No, I heard them in Manchester a few weeks back: they’re not going to make it.’

Just as well I wasn’t trying to become a showbiz reporter.

We trainees were the dogsbodies of the two newspapers, the morning Daily Post and the evening Liverpool Echo, hired basically to be trained up to fill the perpetual shortage of sub-editors processing other people’s copy. You began doing weather and temperatures, checking the Chicago Lard and Hogs prices on the City page, writing up local flower shows and painfully visiting incredibly courteous local families to borrow the mantelpiece picture of a beloved father or son to illustrate an accident report of a death in the docks.

Keen to gain experience and eager to supplement my starting pay of around £850 a year in the hope of being able to start a home with my wife-to-be Carolyn, I used to take on every role I could. Soon I was adding to my basic salary as a ‘sub’ by writing articles, leaders and reviews on a freelance basis under various pseudonyms, even some under the name of ‘Susan Germaine’ for the women’s page. The key opportunity for me though was the discovery that the sports desk had no resident horseracing enthusiast and so ‘Francis Leigh’ (my two middle names) began a series for the Echo ‘Around the Local Stables’, shortly followed by a new racing columnist for the Daily Post who took upon himself the name of ‘Mandarin’, my all-time favourite horse (of whom more at an appropriate stage). When I was summoned one day to the management offices to meet Sir Alick Jeans, the LDP proprietor, I had imagined he might be planning to commend me for all my extra efforts, which nearly doubled both my hours and my salary. Instead all he had to say was, ‘You are earning too much money for a young man of your age.’

The curmudgeonly attitude did not worry me because as well as making progress towards my aim of becoming a political correspondent I was enjoying the opportunity to begin imbibing racing lore from the likes of handicap specialist Eric Cousins, Neston trainer Colin Crossley and the experienced Ron Barnes. That required the purchase of my first car, a second-hand Mini with leopardskin seats. One day it was stolen in Liverpool. The police found it later in Bootle and when I went to collect it the thief had done me a favour: the only thing missing was the leopardskin seat covers!

Before that I used to travel regularly on special raceday coaches packed with shrewd Merseyside regulars to the local tracks of Aintree, Haydock Park and Chester. It was one of my coach companions who told me as we munched our way through cheese and onion baps en route to Haydock one day about a local unlicensed greyhound racing track on Merseyside. It sounded like a different night out and so a Liverpool housemate and I tried it one evening. As I remember, it was somewhere on the fringes of dockland and it made the expression ‘run-down’ sound like an accolade. The dogs were mangy, the handlers, even the female ones, even scruffier: they could have been extras auditioning for the ‘before’ role in dandruff shampoo advertisements. The ramshackle greyhound traps would have lowered the tone of an abandoned allotment and the hare looked like what was left of a well-used washing-up mop. No self-respecting hound would have chased it for more than ten yards. The crowd consisted almost entirely of whey-faced men with pronounced facial tics in long dirty macs.

We hadn’t a clue what we were doing and conversation with scar-faced strangers seemed unwise. What puzzled us most was that most of them didn’t seem to have a bet until 90 seconds before the off when there would be a sudden mini-stampede and clamour to get on two particular dogs which would rapidly be chalked up as first and second favourite. Usually they lost.

After three or four races we were emboldened to step forward while all were hanging back with a couple of £2 reverse forecasts on dogs two and three. Suddenly the place went berserk. As if we had given some secret signal, everyone else rushed in, emptying back pocket wads onto dogs two and three. Amazingly they came first and second, and after the result was confirmed three rather heavy-looking gents whose heads disappeared into their shoulders with no sign of any connecting neck suddenly become our close but silent companions, exuding an air of quiet menace. Whether we had inadvertently stumbled on or interrupted some code or signalling system I will never know, but having collected our winnings it seemed a sensible moment to slip away. As we walked through the gate I turned and waved at the shortest of our three shadows. He did not wave back.

By contrast the horse-watching on Merseyside was a joy. A beautiful sight that I enjoyed on a regular basis and still see in my mind’s eye today was that of Colin Crossley’s string at first light on a summer’s morning cantering along the sands at West Kirby, silhouetted against the sea skyline as they kicked up the spray under stable jockey Eric Apter and colleagues. If they have beaches in the afterlife I will be happy to see any number of reruns.

At Sandy Brow, Tarporley, the former wartime fighter pilot Eric Cousins, who first took out his licence in 1954, proved himself one of the shrewdest placers of horses in the country, winning a couple of Lincoln handicaps, three Ayr Gold Cups, Kempton’s Great Jubilee in four successive years, Ascot’s Wokingham Stakes and the Portland at Doncaster. He did particularly well with cast-offs, as when he won the Cambridgeshire with Commander-in-Chief, formerly trained at Newmarket by Captain Sir Cecil Boyd-Rochfort. It was Eric Cousins of course who introduced his neighbour Robert Sangster to horseracing and the pair brought off a fine coup with Chalk Stream in the 1961 Great Jubilee Handicap at Kempton. Because the horse was a tricky starter Cousins told Sangster to station himself by the bookies and not to have a bet until the trainer raised his hat to show the horse had got off with the others. From high up in the stands Cousins saw the start and doffed his hat. Sangster swung around and took a huge bet at 8-1. The horse got up in the last stride.

I was writing mostly tipping-oriented stable profiles and few of the local trainers’ great thoughts have survived from my notebooks at the time. But I never forgot one experience with Eric Cousins. I began doing some short racing pieces for a BBC North sports programme. The very first time they sent me out with a bulky Uher recorder about the size of an accordion I duly recorded a talk with the Tarporley maestro, only to discover when I got back to the office that the material was completely unusable. Throughout the interview he had been gently rubbing a matchbox on his trousers and it came out on the recording as a noise like a buzz saw. Technology has never been my forte.

I didn’t forget either my first talk with Ron Barnes. Having endured traffic troubles in the Mersey Tunnel I arrived an hour late for an interview at his Norley Bank stables. Quite rightly I was roundly bollocked by the substantial figure of the trainer, built on Sam Hall lines, who bore a fierce scar across his cheek from being grabbed by one of his stable inmates.

Just a few miles from industrial Liverpool we talked, looking down beyond his rock garden to wooded slopes with a mare nuzzling her foal in the paddocks and a two-year-old frisking on a lungeing rein. It was an idyllic scene but Mr Barnes, as the Post and Echo liked me to call trainers in those more deferential days, was going through a lean spell and he began my education in the downside of the trade. Training for Merseyside businessmen who were more likely to spend £500 than 5,000 guineas on their animals in 1965, he had sent out 28 winners. Then after being inoculated against the cough his horses had ‘gone wrong’ and the next season he had won only six races (with the four horses who hadn’t been inoculated). He was the first of many to tell me over the next 40 years that it isn’t training horses that is difficult – it is training the owners.

‘If you can please racehorse owners,’ he said, ‘you can make chains out of sand. When you’re getting winners it’s fine. Everybody wants to buy you champagne and slap your back. Have a lean spell and even your friends don’t want to know you – they’re not interested in explanations. I wouldn’t advise a young man to go into racing until he’s made some money at something else [a policy he followed with his four sons]. There can’t be more than four people in the country who make good money out of training horses. I know if I hadn’t had a bit behind me I would have been finished last year.’

Ron Barnes’s ‘something’ included a building company and a Warrington farm, not to mention 37 acres devoted to his brood mares, and our relations were sufficiently mended by the end of the interview for him to insist on me staying to watch his prize stallion perform. It was the first time I had seen a stallion in action and when the mare was brought into the yard I have never heard such a noise as the roaring he made, nearly kicking to pieces his stall in his eagerness to get out and get on with it.

Ron Barnes’s maxim in preparing his horses was simple: ‘Feed them well and work them to it.’ And on one thing he was adamant: he didn’t bet: ‘If a trainer has to bet he’s got bad owners.’

There were few giants of the training scene on my Merseyside patch in those days but I was given a good introduction to the practicalities at the lower end by the likes of Jack Mason, who had been beaten a neck on Melleray’s Belle in the 1930 Grand National and by just a length in the Scottish version too. He never wanted more than around 20 horses and he told me, ‘I wouldn’t want 10,000 guinea yearlings in my boxes. I’d never get a moment’s rest at the thought – I’d have to sleep with them for fear.’

One who did know what to do with quality though was Rodney Bower, who trained in one of Merseyside’s posher spots in Heswall, in a cobbled yard with an orchard and dovecots. His Border Stud Farm at the time I visited him had sent out Cool Alibi to win the County Hurdle at the Cheltenham Festival and had nearly brought off the double when Border Grace, already by then the winner of sixteen races, had finished second, anchored by an 8lb penalty, in the Mildmay of Flete Challenge Cup. That would have been an amazing achievement for a small yard essentially training just for a few friends – the kind of set-up which for so long provided the backbone of National Hunt racing. They were not a betting yard, but three members of the family did once find themselves picking up more than £1,000 for a fiver each way on the Tote on one of their horses. Very much an advocate of kindness in training horses, Rodney Bower told me, ‘The whole art is discovering the idiosyncrasies of each animal – and they all have them. You don’t want horses too clever – they are usually lazy – but you do want horses with courage. A good horse will strive to get to the front. That’s the kind I like.’

After four years in Liverpool I achieved my aim of being promoted to political correspondent for the Daily Post, based at the House of Commons. Carolyn and I moved south, first to Surbiton and then, by strange coincidence, to Epsom, home of the Derby. It did not however bring to an end my racing articles for the paper. I merely began to interview and profile instead the trainers within easy reach of where we now lived. Even better, until the newspaper’s accountants vetoed it, I had a wonderful perk. The Daily Post used to pay for me to have a ticket on the excursion train which in those days ran from London to Merseyside for the Grand National. I could enjoy a fine breakfast on board, watch the day’s racing and have dinner on the way back while leisurely preparing my copy for the next day for Monday publication.

Grand National

The National has had a special place in my heart ever since my Liverpool days and early images still stick: in 1966 when Anglo won at 50-1 I had bought Mrs Oakley a gorgeous stop-the-traffic pink trouser suit for the occasion. I am not sure which was the more agitated – the horses that passed her in it or my bank manager. An Irish priest whom I met at the Tote window (before an image-conscious church hierarchy forbade it they actually used to attend in their cloth) tipped me Rough Tweed, which was the first horse to fall. So much for divine inspiration.

There were raucous bookies tempting once-a-year punters to make it a fiver with calls of ‘1,000-1 the police horse’, and as I gazed in wonder at the flesh-revealing ensembles adopted by most of female Merseyside I learned the definition of the ‘Mersey tug’, the characteristic gesture with which the heftier young ladies grasp both sides of their bras beneath their dresses to haul them up and rearrange their décolletage. In 1967 I remember I backed the blinkered Popham Down, the horse who brought down most of the field as he ran down the 23rd fence.

I had never experienced a sporting atmosphere like it. You could almost cut the tension in the air as white-faced young riders were swung up into their saddles by leathery-faced trainers in trilbies. You were not human if you were not swept up by the roar from the crowds as the tapes went up and the cavalry charged to the initial obstacle as if there was a stage prize for getting to that first as well. Then as the race unfolded, mini-drama after mini-drama: there would be retreats and advances, blunders and falls. Lumps of spruce would go flying into the air as horses dived through rather than over those big, forbidding fences, and jockeys would be left sitting on the ground beating their whips into the turf in frustration as the remaining field galloped on. Bechers … the Canal Turn … then Melling Road … The Chair and what has became known as ‘the Foinavon fence’ imprinted themselves on the nation’s memories.

It is early in this volume to tackle the downside of our sport but it was those early visits to Aintree which impressed on me so vividly that it involves tragedy as well as triumph, both for the horses who become casualties and their riders. Horses are so noble, so big, so commanding, so athletic in their upright prime that there are few sights in life quite so painfully shocking as when you first see one stricken, threshing on the ground with a broken limb, awaiting the humane despatch that is the only kind response to certain injuries.

It is the plight of the equine casualties that usually engages the media’s attention but alas I will never forget either the sickening spectacle of Paddy Farrell being catapulted out of the saddle at The Chair in a fall in 1964 which was to leave him in a wheelchair for life. You somehow knew as he landed that this was a really bad one – the only good thing in the long run being that it was his injury along with that of Tim Brookshaw which led John Oaksey and others to found a proper compensation scheme for riders in the shape of the Injured Jockeys Fund.

The National today, of course, is not the National I first attended. Many things have changed: the prize money, the fences, the landing surfaces, the quality of horses running in the race, the distance covered to the first obstacle. So am I now going to launch an old fogey’s diatribe about things not being as they were? Am I hell.

I am a defender of the National and I will fight to the death for the race’s retention in the sporting calendar against those who campaign for its abandonment (and who, should they ever achieve that objective, would move on smartly to demand the abolition of jump racing as a whole). But racing has to acknowledge that it lives in a wider world and that animal welfare concerns must be addressed. Those of us who thrill to a sport which inevitably involves casualties to both riders, who choose freely to participate, and horses, who don’t have that luxury, have to be prepared to defend our involvement and to ensure that every possible safety precaution is taken.

Some years it becomes harder than others. After the mudlarks’ benefit 2001 race which he won on Red Marauder, even jockey Richard Guest conceded, ‘I am not sure we should have been out there.’ It did not do much for the image of racing to have only seven horses set out on the second circuit and only two jump round the whole course without a fall. There was an outcry after the National of 1998 when again the race was run in atrocious conditions. Tragically three horses died and only six of the 37 runners finished the course. The Daily Mail in particular ran screaming headlines asking ‘Did three horses really have to die for sport?’ and an article insisting that the event had degenerated into a ‘grisly farce’. ‘This is surely not sport, this is closer to carnage,’ cried the Mail. I was invited by the Independent to contribute to the debate and made the point that the three fatalities occurred at the first, fourth and fifth fences: ‘It was not a cause of exhausted animals at the end of their tether being driven unwilling into the obstacles. They could have died the same way in any race anywhere.’ Their deaths were not justification, I insisted, to ban the National but in what the Racing Post was kind enough to call a ‘balanced analysis’ I suggested that if it had been a midweek fixture in the sticks the card would have been called off, and added, ‘What certainly can be said is that there were a number of horses in the field who were the equine equivalent of vanity publishing. Perhaps the authorities could look again at the race entry conditions to see if more stringent qualifications should be imposed.’ That was a case I had been arguing since the 1970s.

Change for change’s sake as a mere PR exercise I will always resist. It is the besetting sin of modern politics that beneath a media barrage governments insist on being seen to be doing something whether there is a quantifiable benefit or not. Racing is in danger of going the same way. But that does not mean we should resist carefully thought out changes that genuinely increase the safety of horses and riders.

The difficulty that racing faces is that the Grand National is watched by 600 million people in more than 300 countries. It brings in the punters who otherwise don’t focus on a horse race all year and so it is both the sport’s biggest shop window and its biggest potential PR disaster.

The animal rights activists were in full cry again in 2011 when two horses, Ornais and Dooney’s Gate, perished and several horses finished temporarily distressed on an unusually warm day. It did not help racing’s image that winning jockey Jason Maguire received a five-day ban for excessive use of the whip on winner Ballabriggs.

After that the one thing we racing lovers were praying for in the 2012 contest was an incident-free race with every horse coming home safe. That we were denied. Not only did According to Pete have to be put down after being brought down by another horse when running loose after a fall, so did Synchronised, the most high-profile horse in the race since he had won that year’s Cheltenham Gold Cup, was ridden by the champion jockey Tony McCoy, was owned by the multi-millionaire punter J.P. McManus and trained by the National Hunt hero Jonjo O’Neill.

Phone-ins hummed for days with the opinions of the emotional and the ignorant, only every now and then including that rarity, the genuinely informed. Animal rights activists, ranging from those truly concerned with horse welfare to the crudest of class warriors, had their say and once again racing played on the back foot. The RSPCA, which had often in the past worked sensibly with racing’s authorities to maximise safety, came out all guns blazing in 2012, labelling Becher’s Brook a ‘killer fence’ and demanding its scrapping.

I entered the debate with a question: had anybody suggested because the Italian footballer Piermario Morosini had collapsed and died during an Italian Serie B football game or because Fabrice Muamba had suffered a cardiac arrest while playing for Bolton Wanderers that top-level football should therefore be abandoned?

I accept it had its limitations as a parallel. Footballers, those with brain cells anyway, make their own decisions; horses do not. But the key point is that we cannot eliminate risk from sport, or from life.

As for that year’s Grand National, I tried to emphasise a few facts. Synchronised was not injured because he was driven beyond his limits: he was put down because he broke his leg, not in the fall where he lost his jockey, nor even jumping another fence when running loose; the accident happened, to the enormous regret of owner, trainer and jockey, on the Flat. He took a false step and shattered his leg.

It was at Becher’s that According to Pete broke his off-fore when ‘falling’ but in fact he jumped the fence well: he simply had nowhere to go then because another horse, On His Own, had fallen ahead of him. The irony was that ‘improvements’ to Becher’s following past protests probably did for According to Pete. What the professionals tell you is that easing Becher’s in previous modifications has made jockeys less fearful of the fence. Instead of fanning out across the course to tackle it they now go faster and crowd in. That, it seems, is what unsighted On His Own and caused him to fall.

It is doubtful if changing any regulation could have prevented either death but on went the furore: scrap the National, scrap horseracing, let horses run free in fields, the animal rights campaigners were urging. But the week before, Great Endeavour, a quality chaser, was in a field owned by jockey Timmy Murphy, starting his summer holiday. No race was involved, there was no fence to jump, but he too broke a leg and died. Should we ban keeping horses in fields? Accidents happen and horses, because a broken leg in their case almost always means that life is unbearable or unsustainable, are especially vulnerable.

Fences are the problem, say the campaigners, for now. End jump racing. Keep it to the Flat. But three horses died in a night’s racing at 2012’s Dubai World Cup, where no horse has ever been asked to jump a single obstacle.

To listen to the campaigners, you would think there was constant carnage. Every death is sad, as those of us who spend time with jockeys, trainers or stable staff are especially aware. But that year horses participated in jumping races on 94,776 occasions. From that number, 181 horses received injuries which led to their deaths, a rate of 0.19 per cent. Not a bad comparison with your chances crossing the road.

It was little wonder that one racecourse chief told me before the 2013 contest, ‘This year we’ll all be watching from behind the sofa.’ In fact, after the 2012 race three more ‘drop’ fences had their landing areas levelled out, and to calm the cavalry charge of 40 horses to the first fence the start was moved 90 yards closer to it, taking jockeys and horses away from the adrenalin-inducing hubbub from the stands. In the 2013 race, won by Aurora’s Encore, that seemed to help, with jockeys taking the early stages less recklessly. Also since 2012, six-year-olds have not been allowed to run in the National and participants must previously have finished fourth or better in a three-mile chase.

I thoroughly approve of one change we saw in the 2013 race. Those big Aintree fences are now being built around plastic cores rather than timber posts, which can prove a fearsome obstacle on the second circuit when first-round fencers have kicked the spruce off them. That should probably have happened sooner and the fact is that serious, organised, well-informed campaigners have won some improvements over the years. Racing in the old days was too careless of the risks. But over recent years Aintree in particular and the horseracing authorities have responded to informed criticism with many changes designed to improve safety. We may even have gone too far: making the fences easier, some jockeys are warning, is making horses go faster and increasing, not diminishing, the injury risks. What we need now is a pause for the changes to bed in. What we seem to be forgetting, in an age when firemen are forbidden to wade into five-feet-deep ponds on health and safety grounds, is that the Grand National is not supposed to be like every other race: it is a unique sporting spectacle which engages the nation like no other and wins a TV audience far beyond any other race. It holds that position precisely because its fences are special, because at four miles plus it is longer than other races and because more horses take part than in other races.

We are now at a turning point. Yes, let us have careful statistical surveys and annual reviews. If practical steps can be taken to reduce falls and injuries by, for example, eliminating more drop fences where the landing point is lower than the take-off, let us implement them. But we cannot eliminate all risk or all casualties from a sport which involves half a ton of horse jumping obstacles at speed. Muck about much more with the Grand National and it won’t any longer be grand or national, it will be just another lengthy steeplechase that there is no point in anybody tuning in to watch. And then how many of the horses who race over jumps today will even exist?

What many now forget is that in the 1970s the race did nearly die. Property developer Bill Davies had bought the course from Muriel Topham and tripled admission prices, with the result that when Red Rum beat L’Escargot in 1975 it was in front of the smallest crowd in living memory. So thank heavens for Ladbrokes who rescued the race in dark times before handing it on to the Jockey Club. Thank heavens too for handicapper Phil Smith who has set the weights for the National since 1999 and compressed the handicap to bring much better quality horses into the top end of the National field. For example he reduced the top weight from the crushing 12 stone to 11st 12lb

For many years large sections of the National field were running ‘out of the handicap’. Because there is a minimum weight carried in the race of 10st 0lb (to ensure there are enough jockeys available) many horses which would have been given weights below 10 stone in terms of their ability were running carrying excess weight and with little chance. But with Martell and then John Smith’s raising the prize money, better horses were attracted. Thanks to that and the higher achievement levels required from would-be participants, we do now get a better quality of race, even if the likes of Mon Mome at 100-1 and Aurora’s Encore at 66-1 still give the bookies an occasional bonanza day in the biggest betting race of the year. Now almost every year the horses running in the National are doing so carrying the weight appropriate to their rating. It has become a proper handicap.

I talked to Phil Smith one year about how he made his assessments and he replied that he normally weighted horses on their form over three miles on tracks like Haydock or Kempton but he took into account the fact that Aintree was different and the race was much longer:

For the higher weighted horses I try to reduce the amount of weight they carry, bearing in mind that the further they travel the more likely the weight is to have an effect. You and I might be able to run a hundred metres carrying a bag of sugar under each arm but if we have to run two hundred metres with the same burden we are going to notice it more.

Even handicappers can get things wrong of course. When Monty’s Pass landed a huge £1 million-plus gamble by winning the National in 2003, Phil Smith was so confident of his handicapping that he had promised to jump off the roof of the stands if anything won by more than seven lengths. At the line there was twelve lengths between Monty’s Pass and the second.

When Phil Smith took over, no horse carrying more than 11 stone had won since Jenny Pitman’s Corbiere won in 1983. Not until 2005 when Hedgehunter won with 11st 1lb was that statistic overturned. By 2009 all the first four home carried 11 stone or more.

We all have Nationals we remember more vividly than others. I once worked on the Sunday Express alongside ex-jockey Dick Francis and like millions I have never forgotten his mount Devon Loch’s collapse on the run-in in 1956, replayed so many times on grainy old newsreels. Nor will I ever forget the gallant effort by the top weight Crisp when Red Rum won for the first time in 1973. Crisp was carrying the maximum 12 stone, Red Rum 23lbs less and the only time Red Rum was in front was in the last ten yards. Crisp’s rider Richard Pitman is one of the nicest guys on the National Hunt scene and unfairly blames himself for his mugging at the finish by Ginger McCain’s charge. Trainer Fred Winter had intended Richard on Crisp to make the running and slow the pace from the front but there was no way the big black Crisp, an Australian import, was going to settle for that. The moment he had jumped one fence he wanted to attack the next and at one stage must have been forty lengths ahead of his field. Unfortunately he could not quite last home as Red Rum came after him but even coming second was for Richard, who had won races like the King George, the Hennessy and the Champion Hurdle, the most exhilarating ride of his life.

The greatest recovery I ever saw was Brendan Powell’s success in 1988 on Rhyme n’ Reason. Jumping Becher’s the first time round, the horse lost his legs on landing and slithered many yards on his belly. By the time the pair set off again they were last of the 33 still standing. Gradually Brendan picked off the rest of the field and came with a great burst of speed after the last to beat Durham Edition and Monamore.

Others perhaps would choose the success by Josh Gifford’s ex-invalid Aldaniti, ridden by cancer sufferer Bob Champion to win in 1981, as the ultimate fairy story turned into reality but for me Amberleigh House’s success in 2004 was special. At Aintree I never missed the chance of a few words with Ginger McCain when I could get them, even if all he was in the mood for was the bluest of blue jokes, and I wrote that weekend:

Beside the parade ring as the wind sent the petals from the flowering cherries swirling around Philip Blacker’s bronze of Red Rum, three times the winner of the Grand National and twice second in the big race, groups congregated for family photos. Somebody had placed a bunch of red roses between the old boy’s forelegs. Inside the track, hundreds passed Red Rum’s daffodil-bedecked grave in the shadow of the winning post. Don’t ever let anybody tell you that the Grand National has lost, or ever could lose, its magic.

Trainer Ginger McCain, who won Saturday’s race with Amberleigh House 27 years after his endeavours with Red Rum, does not forget it, declaring, ‘You can have your Gold Cups at Ascot with those toffee-nosed people, you can have your Cheltenham Festival with all your county set types and tweeds. But this is the people’s race.’

He recalled when he first came to Aintree in 1938 or 1939 watching the race from the embankment on the canal: ‘We never saw a horse. Heard the crack of the fences, saw some caps go by but it was all part and parcel of the magic of this game. The turf is torn, the spruce from the fences has been kicked all over the course … in those days there would be three jockeys coming back on one horse or a jockey who’d pulled up coming back leading another faller.’

Winning owner John Halewood is a Merseysider too. These days he has his own box but he remembers coming with his father, who died soon afterwards, early in the 1980s. They went round to the Canal Turn because they could not afford the Members Enclosure and his father said to him, ‘One day you might own a horse.’

As for Ginger, ruddy of face, forthright in his opinions, with a twinkle in his eye and so appreciative at 73 of the skimpily wrapped curves on offer at Aintree that he claimed to have been off looking for some little blue pills, he is part of what racing is all about. Trainer Mick O’Toole once declared, ‘Racing is a game of make believe. If people didn’t think they had horses that were better than they really were, National Hunt racing would collapse.’

You have to have that dream, as John Halewood did when he paid 90,000 punts for his National winner. But Ginger, now based in Cheshire, did have doubts when Amberleigh House arrived in his yard. ‘It was three o’clock in the morning, teeming with rain and I was in dressing gown and slippers. The horsebox driver let down the ramp and there was this tiny horse shivering in the corner of the box, no rug, no head collar, and I said, “That’s not him, that’s not the Amberleigh House I saw win at Punchestown.” You know how the Irish like to stitch up us English trainers. But what a grand little horse he’s been.’

Many thought Ginger, who has been insisting for three years that he had another potential National winner even when the horse was so lowly handicapped that he could not get into the race, reckoned he was dreaming a dream too far. He thought his best chance might have gone when Amberleigh House was third last year. But he is happy to take older horses to Aintree, reckoning that while they may be beaten by younger animals round some of the easier park courses, the challenge of the big Aintree fences revives them by making them think where impetuous younger horses blunder their chances away.

I had in earlier days seen Ginger, who was by then based in Cheshire and enjoying the assistance of his canny and courteous son Donald [whose Ballabriggs was to continue family tradition by winning the 2011 National], exercising his horses on the Southport sands behind his used car salerooms. Ginger was old-school and proud of it in what we usually hoped was his tongue-in-cheek way: ‘As for no French-bred horse winning the National since 1909 – everyone goes on about the French-breds. You’d think there was something magical about buying them. But Ryan Price bought them, Eric Cousins used to buy them. They talk about them being taught to jump when they are two years old and all that but they don’t last. They’re not like a big store-bred four-year-old that you get and break in with no mileage on the clock. Horses are like cars: you’ve only got so much mileage in them and when that’s gone you’ve got nothing.’

Ginger, who was clearly no Lib Dem voter, goes on: ‘They bring in this Yogi Breisner (the Scandinavian jumping guru much in demand with southern trainers and riders) – he’s not a bleeding Englishman, he’s not even an Irishman. Any trainer that has to bring in a foreigner to teach his horses how to jump should hand his bloody licence in because he’s not entitled to it.’

That, I commented, should cause a few winces over Lambourn’s breakfast tables. And if such opinions brought Ginger within dangerous reach of the Race Relations Act, he had the Equal Opportunities people gasping the next year when trainer’s wife Carrie Ford, twice the leading woman jockey over jumps, was riding Forest Gunner in the National. She had been in the saddle for that horse’s victory in the Foxhunters Chase just ten weeks after giving birth to daughter Hannah but Ginger dismissed her chance in the big race, declaring ‘Carrie is a broodmare now and having kids doesn’t get you fit to ride.’

But if Ginger was entitled to a little sounding-off after Amberleigh House’s victory, others too had played a notable part, notably the horse himself who, said his jockey Graham Lee, was baulked so badly at Becher’s that he took it virtually from a standing start. Lee too deserves enormous credit for his coolness. So often, races are given away by premature moves, particularly on such a highly charged occasion as a Grand National. Graham and Donald McCain, the trainer’s son, had planned for him to ride a waiting race but the mayhem ahead of him had ensured that Amberleigh House was much further behind the leaders than they had hoped. When the horses came back into the straight with Amberleigh House still apparently out of contention, Lee did not rush to make up his ground as he felt a strong headwind. ‘When I felt I should have been going for him I thought, well, I’ll count to ten first because he’s only got one run.’ He let the others came back to him. As a result Amberleigh House’s run came just as Clan Royal and Lord Atterbury, punch drunk, were beginning to roll all over the course. [Hedgehunter had fallen at the last.] That was a ten-second delay that probably won a National.

Whoever would have thought, as Graham Lee described the National victory as the best day of his life, that in 2012 he would return to the Flat racing career that had failed to take off before and ride a hundred winners that season.

Another National was special for me because it was won by the best jockey I will ever see over jumps, Tony McCoy. It was special for AP too, not just because he landed the race at his fifteenth attempt (it took Frankie Dettori the same number of attempts to win his first Derby) but because I believe it was the moment when the iron man of racing truly learned how much the racing public adored him.

Biblical scholars say five is the number of grace, three the number of perfection. ‘Fifteen therefore relates to acts wrought by divine grace.’ I don’t know if Tony McCoy was saying his prayers as his mount Don’t Push It cleared the last and headed round The Elbow for the Grand National finishing line but he deserved any divine intervention that was going.

So too did the punters who had backed Don’t Push It all the way down from 25-1 to 10-1 favourite. That didn’t happen because of anything in the horse’s form. Only one horse in the previous 25 years had carried more than eleven stone to victory and Don’t Push It carried 11st 5lb. Only seven of the previous 50 favourites had won and although he had a touch of class, Don’t Push It was a quirky, unsociable individual who spent most of his time out in a field with sheep and never ran two races alike. The money was there for him simply because AP is a riding phenomenon, the champion for eighteen consecutive years in a sport in which simply keeping your body roughly in one piece for a full season is an achievement.

AP is utterly professional, totally dedicated to winning and afraid of nothing. At the Cheltenham Festival that year his body had taken a terrible battering in two crunching falls. But that didn’t stop him riding the winner of the Champion Hurdle, bringing Denman home second in the Gold Cup and riding a race on Alberta’s Run in the Ryanair Chase which was both a masterpiece of tactical riding and a testament to his gritty determination.

For racing folk AP’s victory at Aintree was all the sweeter because it was achieved in conjunction with two others who had also seemed to suffer a National hoodoo. Don’t Push It’s owner J.P. McManus, the greatest patron jump racing has ever had (and a man who looks after all his old horses after their racing days are done), had unsuccessfully run 44 horses before Don’t Push It in his bid to win the race. Trainer Jonjo O’Neill, another great jockey in his time, never got round the National course as a rider and had yet to prepare a horse to win it.