Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

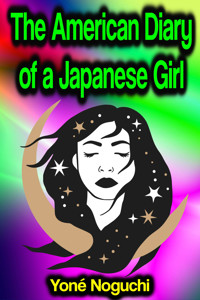

The American Diary of a Japanese Girl - Yoné Noguchi - The American Diary of a Japanese Girl is the first English-language novel published in the United States by a Japanese writer. Acquired for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Monthly Magazine by editor Ellery Sedgwick in 1901, it appeared in two excerpted installments in November and December of that year with illustrations by Genjiro Yeto. In 1902, it was published in book form by the New York firm of Frederick A. Stokes. Marketed as the authentic diary of an 18-year-old female visitor to the United States named "Miss Morning Glory" (Asagao), it was in actuality the work of Yone Noguchi, who wrote it with the editorial assistance of Blanche Partington and Léonie Gilmour. The book describes Morning Glory's preparations, activities and observations as she undertakes her transcontinental American journey with her uncle, a wealthy mining executive. Arriving in San Francisco by steamship, they stay briefly at the Palace Hotel before moving to a "high-toned boarding house" in Nob Hill. Through the American wife of the Japanese consul, Morning Glory befriends Ada, a denizen of Van Ness Avenue with a taste for coon songs, who introduces her to Golden Gate Park and vaudeville and is in turn initiated by Morning Glory in the ways of kimono. Morning Glory briefly takes over proprietorship of a cigar store on the edge of San Francisco Chinatown before moving to the rustic Oakland home of an eccentric local poet named Heine (a character based on Joaquin Miller). After some days there spent developing her literary skills and a romantic interest with local artist Oscar Ellis, and a brief excursion to Los Angeles, she departs with her uncle for Chicago and New York, continuing, along the way, her satirical observations on various aspects of American life and culture. The novel closes with Morning Glory's declared intention to continue her investigations into American life by taking a job as a domestic servant, thus preparing the way for a sequel. Noguchi had already written the sequel, The American Letters of a Japanese Parlor-Maid, at the time of the American Diary's publication, but Stokes, citing lackluster sales, declined to publish the sequel, thus obliging Noguchi to defer publication until his return to Japan in 1904. There, Tokyo publisher Fuzanbo issued a new edition of The American Diary of a Japanese Girl (this time under Noguchi's own name, with an appendix documenting the book's history) as well as The American Letters of a Japanese Parlor-Maid (1905), published with a preface by Tsubouchi Shoyo. Another publisher issued Noguchi's Japanese translation of The American Diary of a Japanese Girl. In 1912, Fuzanbo published a new edition of The American Diary with a fold-out illustration (kuchi-e) by ukiyo-e artist Eiho Hirezaki, which was also sold under the imprint of London publisher and bookseller Elkin Mathews. In 2007, The American Diary of a Japanese Girl was reissued in an annotated edition by Temple University Press.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 196

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Her Majesty

HARUKO

Empress of Japan

January, 1902

Ever since my childhood, thy sovereign beauty has been all to me in benevolence and inspiration.

How often I watched thy august presence in happy amazement when thou didst pass along our Tokio streets! What a sad sensation I had all through me when thou wert just out of sight! If thou only knewest, I prayed, that I was one of thy daughters! I set it in my mind, a long time ago, that anything I did should be offered to our mother. How I wish I could say my own mother! Mother art thou, heavenly lady!

I am now going to publish my simple diary of my American journey.

And I humbly dedicate it unto thee, our beloved Empress, craving that thou wilt condescend to acknowledge that one of thy daughters had some charming hours even in a foreign land.

Morning Glory

BEFORE I SAILED

BEFORE I SAILED

Tokio, Sept. 23rd

My new page of life is dawning.

A trip beyond the seas—Meriken Kenbutsu—it’s not an ordinary event.

It is verily the first event in our family history that I could trace back for six centuries.

My to-day’s dream of America—dream of a butterfly sipping on golden dews—was rudely broken by the artless chirrup of a hundred sparrows in my garden.

“Chui, chui! Chui, chui, chui!”

Bad sparrows!

My dream was silly but splendid.

Dream is no dream without silliness which is akin to poetry.

If my dream ever comes true!

24th—The song of gay children scattered over the street had subsided. The harvest moon shone like a yellow halo of “Nono Sama.” All things in blessed Mitsuho No Kuni—the smallest ant also—bathed in sweet inspiring beams of beauty. The soft song that is not to be heard but to be felt, was in the air.

’Twas a crime, I judged, to squander lazily such a gracious graceful hour within doors.

I and my maid strolled to the Konpira shrine.

Her red stout fingers—like sweet potatoes—didn’t appear so bad tonight, for the moon beautified every ugliness.

Our Emperor should proclaim forbidding woman to be out at any time except under the moonlight.

Without beauty woman is nothing. Face is the whole soul. I prefer death if I am not given a pair of dark velvety eyes.

What a shame even woman must grow old!

One stupid wrinkle on my face would be enough to stun me.

My pride is in my slim fingers of satin skin.

I’ll carefully clean my roseate finger-nails before I’ll land in America.

Our wooden clogs sounded melodious, like a rhythmic prayer unto the sky. Japs fit themselves to play music even with footgear. Every house with a lantern at its entrance looked a shrine cherishing a thousand idols within.

I kneeled to the Konpira god.

I didn’t exactly see how to address him, being ignorant what sort of god he was.

I felt thirsty when I reached home. Before I pulled a bucket from the well, I peeped down into it. The moonbeams were beautifully stealing into the waters.

My tortoise-shell comb from my head dropped into the well.

The waters from far down smiled, heartily congratulating me on going to Amerikey.

25th—I thought all day long how I’ll look in ’Merican dress.

26th—My shoes and six pairs of silk stockings arrived.

How I hoped they were Nippon silk!

One pair’s value is 4 yens.

Extravagance! How dear!

I hardly see any bit of reason against bare feet.

Well, of course, it depends on how they are shaped.

A Japanese girl’s feet are a sweet little piece. Their flatness and archlessness manifest their pathetic womanliness.

Feet tell as much as palms.

I have taken the same laborious care with my feet as with my hands. Now they have to retire into the heavy constrained shoes of America.

It’s not so bad, however, to slip one’s feet into gorgeous silk like that.

My shoes are of superior shape. They have a small high heel.

I’m glad they make me much taller.

A bamboo I set some three Summers ago cast its unusually melancholy shadow on the round paper window of my room, and whispered, “Sara! Sara! Sara!”

It sounded to me like a pallid voice of sayonara.

(By the way, the profuse tips of my bamboo are like the ostrich plumes of my new American hat.)

“Sayonara” never sounded before more sad, more thrilling.

My good-bye to “home sweet home” amid the camellias and white chrysanthemums is within ten days. The steamer “Belgic” leaves Yokohama on the sixth of next month. My beloved uncle is chaperon during my American journey.

27th—I scissored out the pictures from the ’Merican magazines.

(The magazines were all tired-looking back numbers. New ones are serviceable in their own home. Forgotten old actors stray into the villages for an inglorious tour. So it is with the magazines. Only the useless numbers come to Japan, I presume.)

The pictures—Meriken is a country of woman; that’s why, I fancy, the pictures are chiefly of woman—showed me how to pick up the long skirt. That one act is the whole “business” of looking charming on the street. I apprehend that the grace of American ladies is in the serpentine curves of the figure, in the narrow waist.

Woman is the slave of beauty.

I applied my new corset to my body. I pulled it so hard.

It pained me.

28th—My heart was a lark.

I sang, but not in a trembling voice like a lark, some slices of school song.

I skipped around my garden.

Because it occurred to me finally that I’ll appear beautiful in my new costume.

I smiled happily to the sunlight whose autumnal yellow flakes—how yellow they were!—fell upon my arm stretched to pluck a chrysanthemum.

I admit that my arm is brown.

But it’s shapely.

29th—English of America—sir, it is light, unreserved and accessible—grew dear again. My love of it returned like the glow in a brazier that I had watched passionately, then left all the Summer days, and to which I turned my apologetic face with Winter’s approaching steps.

Oya, oya, my book of Longfellow under the heavy coat of dust!

I dusted the book with care and veneration as I did a wee image of the Lord a month ago.

The same old gentle face of ’Merican poet—a poet need not always to sing, I assure you, of tragic lamentation and of “far-beyond”—stared at me from its frontispiece. I wondered if he ever dreamed his volume would be opened on the tiny brown palms of a Japan girl. A sudden fancy came to me as if he—the spirit of his picture—flung his critical impressive eyes at my elaborate cue with coral-headed pin, or upon my face.

Am I not a lovely young lady?

I had thrown Longfellow, many months ago, on the top shelf where a grave spider was encamping, and given every liberty to that reticent, studious, silver-haired gentleman Mr. Moth to tramp around the “Arcadie.”

Mr. Moth ran out without giving his own “honourable” impression of the popular poet, when I let the pages flutter.

Large fatherly poet he is, but not unique. Uniqueness, however, has become commonplace.

Poet of “plain” plainness is he—plainness in thought and colour. Even his elegance is plain enough.

I must read Mr. Longfellow again as I used a year ago reclining in the Spring breeze,—“A Psalm of Life,” “The Village Blacksmith,” and half a dozen snatches from “Evangeline” or “The Song of Hiawatha” at the least. That is not because I am his devotee—I confess the poet of my taste isn’t he—but only because he is a great idol of American ladies, as I am often told, and I may suffer the accusation of idiocy in America, if I be not charming enough to quote lines from his work.

30th—Many a year I have prayed for something more decent than a marriage offer.

I wonder if the generous destiny that will convey me to the illustrious country of “woman first” isn’t the “something.”

I am pleased to sail for Amerikey, being a woman.

Shall I have to become “naturalized” in America?

The Jap “gentleman”—who desires the old barbarity—persists still in fancying that girls are trading wares.

When he shall come to understand what is Love!

Fie on him!

I never felt more insulted than when I was asked in marriage by one unknown to me.

No Oriental man is qualified for civilisation, I declare.

Educate man, but—beg your pardon—not the woman!

Modern gyurls born in the enlightened period of Meiji are endowed with quite a remarkable soul.

I act as I choose. I haven’t to wait for my mamma’s approval to laugh when I incline to.

Oct. 1st—I stole into the looking-glass—woman loses almost her delight in life if without it—for the last glimpse of my hair in Japan style.

Butterfly mode!

I’ll miss it adorning my small head, while I’m away from home.

I have often thought that Japanese display Oriental rhetoric—only oppressive rhetoric that palsies the spirit—in hair dressing. Its beauty isn’t animation.

I longed for another new attraction on my head.

I felt sad, however, when I cut off all the paper cords from my hair.

I dreaded that the American method of dressing the hair might change my head into an absurd little thing.

My lengthy hair languished over my shoulders.

I laid me down on the bamboo porch in the pensive shape of a mermaid fresh from the sea.

The sportive breezes frolicked with my hair. They must be mischievous boys of the air.

I thought the reason why Meriken coiffure seemed savage and without art was mainly because it prized more of natural beauty.

Naturalness is the highest of all beauties.

Sayo shikaraba!

Let me learn the beauty of American freedom, starting with my hair!

Are you sure it’s not slovenliness?

Woman’s slovenliness is only forgiven where no gentleman is born.

2nd—Occasional forgetfulness, I venture to say, is one of woman’s charms.

But I fear too many lapses in my case fill the background.

I amuse myself sometimes fancying whether I shall forget my husband’s name (if I ever have one).

How shall I manage “shall” and “will”? My memory of it is faded.

I searched for a printed slip, “How to use Shall and Will.” I pressed to explore even the pantry after it.

Afterward I recalled that Professor asserted that Americans were not precise in grammar. The affirmation of any professor isn’t weighty enough. But my restlessness was cured somehow.

“This must be the age of Jap girls!” I ejaculated.

I was reading a paper on our bamboo land, penned by Mr. Somebody.

The style was inferior to Irving’s.

I have read his gratifying “Sketch Book.” I used to sleep holding it under my wooden pillow.

Woman feels happy to stretch her hand even in dream, and touch something that belongs to herself. “Sketch Book” was my child for many, many months.

Mr. Somebody has lavished adoring words over my sisters.

Arigato! Thank heavens!

If he didn’t declare, however, that “no sensible musume will prefer a foreign raiment to her kimono!”

He failed to make of me a completely happy nightingale.

Shall I meet the Americans in our flapping gown?

I imagined myself hitting off a tune of “Karan Coron” with clogs, in circumspect steps, along Fifth Avenue of somewhere. The throng swarmed around me. They tugged my silken sleeves, which almost swept the ground, and inquired, “How much a yard?” Then they implored me to sing some Japanese ditty.

I’ll not play any sensational rôle for any price.

Let me remain a homely lass, though I express no craft in Meriken dress.

Do I look shocking in a corset?

“In Pekin you have to speak Makey Hey Rah” is my belief.

3rd—My hand has seldom lifted anything weightier than a comb to adjust my hair flowing down my neck.

The “silver” knife (large and sharp enough to fight the Russians) dropped and cracked a bit of the rim of the big plate.

My hand tired.

My uncle and I were seated at a round table in a celebrated American restaurant, the “Western Sea House.”

It was my first occasion to face an orderly heavy Meriken table d’hote.

Its fertile taste was oily, the oppressive smell emetic.

Must I make friends with it?

I am afraid my small stomach is only fitted for a bowl of rice and a few cuts of raw fish.

There is nothing more light, more inviting, than Japanese fare. It is like a sweet Summer villa with many a sliding shoji from which you smile into the breeze and sing to the stars.

Lightness is my choice.

When, I wondered, could I feel at home with American food!

My uncle is a Meriken “toow.” He promised to show me a heap of things in America.

He is an 1884 Yale graduate. He occupies the marked seat of the chief secretary of the “Nippon Mining Company.” He has procured leave for one year.

What were the questionable-looking fragments on the plate?

Pieces with pock-marks!

Cheese was their honourable name.

My uncle scared me by saying that some “charming” worms resided in them.

Pooh, pooh!

They emitted an annoying smell. You have to empty the choicest box of tooth powder after even the slightest intercourse with them.

I dare not make their acquaintance—no, not for a thousand yens.

I took a few of them in my pocket papers merely as a curiosity.

Shall I hang them on the door, so that the pest may not come near to our house?

(Even the pest-devils stay away from it, you see.)

4th—The “Belgic” makes one day’s delay. She will leave on the seventh.

“Why not one week?” I cried.

I pray that I may sleep a few nights longer in my home. I grow sadder, thinking of my departure.

My mother shouldn’t come to the Meriken wharf. Her tears may easily stop my American adventure.

I and my maid went to our Buddhist monastery.

I offered my good-bye to the graves of my grandparents. I decked them with elegant bunches of chrysanthemums.

When we turned our steps homeward the snowy-eyebrowed monk—how unearthly he appeared!—begged me not to forget my family’s church while I am in America.

“Christians are barbarians. They eat beef at funerals,” he said.

His voice was like a chant.

The winds brought a gush of melancholy evening prayer from the temple.

The tolling of the monastery bell was tragic.

“Goun! Goun! Goun!”

5th—A “chin koro” barked after me.

The Japanese little doggie doesn’t know better. He has to encounter many a strange thing.

The tap of my shoes was a thrill to him. The rustling of my silk skirt—such a volatile sound—sounded an alarm to him.

I was hurrying along the road home from uncle’s in Meriken dress.

What a new delight I felt to catch the peeping tips of my shoes from under my trailing koshi goromo.

I forced my skirt to wave, coveting a more satisfactory glance.

Did I look a suspicious character?

I was glad, it amused me to think the dog regarded me as a foreign girl.

Oh, how I wished to change me into a different style! Change is so pleasing.

My imitation was clever. It succeeded.

When I entered my house my maid was dismayed and said:

“Bikkuri shita! You terrified me. I took you for an ijin from Meriken country.”

“Ho, ho! O ho, ho, ho!”

I passed gracefully (like a princess making her triumphant exit in the fifth act) into my chamber, leaving behind my happiest laughter and shut myself up.

Drawn by Genjiro Yeto “A new delight to catch the peeping tips of my shoes”

I confess that I earned the most delicious moment I have had for a long time.

I cannot surrender under the accusation that Japs are only imitators, but I admit that we Nippon daughters are suited to be mimics.

Am I not gifted in the adroit art?

Where’s Mr. Somebody who made himself useful to warn the musumes?

Then I began to rehearse the scene of my first interview with a white lady at San Francisco.

I opened Bartlett’s English Conversation Book, and examined it to see if what I spoke was correct.

I sat on the writing table. Japanese houses set no chairs.

(Goodness, mottainai! I sat on the great book of Confucius.)

The mirror opposite me showed that I was a “little dear.”

6th—It rained.

Soft, woolen Autumn rain like a gossamer!

Its suggestive sound is a far-away song which is half sob, half odor. The October rain is sweet sad poetry.

I slid open a paper door.

My house sits on the hill commanding a view over half Tokio and the Bay of Yedo.

My darling city—with an eternal tea and cake, with lanterns of festival—looked up to me through the gray veil of rain.

I felt as if Tokio were bidding me farewell.

Sayonara! My dear city!

GOOD NIGHT—NATIVE LAND!

ON THE OCEAN

“Belgic,” 7th

Good night—native land!

Farewell, beloved Empress of Dai Nippon!

12th—The tossing spectacle of the waters (also the hostile smell of the ship) put my head in a whirl before the “Belgic” left the wharf.

The last five days have been a continuous nightmare. How many a time would I have preferred death!

My little self wholly exhausted by sea-sickness. Have I to drift to America in skin and bone?

I felt like a paper flag thrown in a tempest.

The human being is a ridiculously small piece. Nature plays with it and kills it when she pleases.

I cannot blame Balboa for his fancy, because he caught his first view from the peak in Darien.

It’s not the “Pacific Ocean.” The breaker of the world!

“Do you feel any better?” inquired my fellow passenger.

He is the new minister to the City of Mexico on his way to his post. My uncle is one of his closest friends.

What if Meriken ladies should mistake me for the “sweet” wife of such a shabby pock-marked gentleman?

It will be all right, I thought, for we shall part at San Francisco.

(The pock-mark is rare in America, Uncle said. No country has a special demand for it, I suppose.)

His boyish carelessness and samurai-fashioned courtesy are characteristic. His great laugh, “Ha, ha, ha!” echoes on half a mile.

He never leaves his wine glass alone. My uncle complains of his empty stomach.

The more the minister repeats his cup the more his eloquence rises on the Chinese question. He does not forget to keep up his honourable standard of diplomatist even in drinking, I fancy.

I see charm in the eloquence of a drunkard.

I exposed myself on deck for the first time.

I wasn’t strong enough, alas! to face the threatening grandeur of the ocean. Its divineness struck and wounded me.

O such an expanse of oily-looking waters! O such a menacing largeness!

One star, just one sad star, shone above.

I thought that the little star was trembling alone on a deck of some ship in the sky.

Star and I cried.

13th—My first laughter on the ocean burst out while I was peeping at a label, “7 yens,” inside the chimney-pot hat of our respected minister, when he was brushing it.

He must have bought that great headgear just on the eve of his appointment.

How stupid to leave such a bit of paper!

I laughed.

He asked what was so irresistibly funny.

I laughed more. I hardly repressed “My dear old man.”

The “helpless me” clinging on the bed for many a day feels splendid to-day.

The ocean grew placid.

On the land my eyes meet with a thousand temptations. They are here opened for nothing but the waters or the sun-rays.

I don’t gain any lesson, but I have learned to appreciate the demonstrations of light.

They were white. O what a heavenly whiteness!

The billows sang a grand slow song in blessing of the sun, sparkling their ivory teeth.

The voyage isn’t bad, is it?

I planted myself on the open deck, facing Japan.

I am a mountain-worshipper.

Alas! I could not see that imperial dome of snow, Mount Fuji.

One dozen fairies—two dozen—roved down from the sky to the ocean.

I dreamed.

I was so very happy.

14th—What a confusion my hair has suffered! I haven’t put it in order since I left the Orient. Such negligence of toilet would be fined by the police in Japan.

I was busy with my hair all the morning.

15th—The Sunday service was held.

There’s nothing more natural on a voyage than to pray.

We have abandoned the land. The ocean has no bottom.

We die any moment “with bubbling groan, without a grave, unknelled, uncoffined, and unknown.”

Only prayer makes us firm.

I addressed myself to the Great Invisible whose shadow lies across my heart.

He may not be the God of Christianity. He is not the Hotoke Sama of Buddhism.

Why don’t those red-faced sailors hum heavenly-voiced hymns instead of—“swear?”

16th—Amerikey is away beyond.

Not even a speck of San Francisco in sight yet!

I amused myself thinking what would happen if I never returned home.

Marriage with a ’Merican, wealthy and comely?

I had well-nigh decided that I would not cross such an ocean again by ship. I would wait patiently until a trans-Pacific railroad is erected.

I was basking in the sun.

I fancied the “Belgic” navigating a wrong track.

What then?

Was I approaching lantern-eyed demons or howling cannibals?

“Iya, iya, no! I will proudly land on the historical island of Lotos Eaters.” I said.

Why didn’t I take Homer with me? The ocean is just the place for his majestic simplicity and lofty swing.

I recalled a few passages of “The Lotos Eaters” by Lord Tennyson—it sounds better than “the poet Tennyson.” I love titles, but they are thought as common as millionaires nowadays.

A Jap poet has a different mode of speech.

Shall I pose as poet?

’Tis no great crime to do so.

I began my “Lotos Eaters” with the following mighty lines:

“O dreamy land of stealing shadows!

O peace-breathing land of calm afternoon!

O languid land of smile and lullaby!

O land of fragrant bliss and flower!

O eternal land of whispering Lotos Eaters!”

Then I feared that some impertinent poet might have said the same thing many a year before.

Poem manufacture is a slow job.

Modern people slight it, calling it an old fashion. Shall I give it up for some more brilliant up-to-date pose?

17th—I began to knit a gentleman’s stockings in wool.

They will be a souvenir of this voyage.

(I cannot keep a secret.)

I tell you frankly that I designed them to be given to the gentleman who will be my future “beloved.”

The wool is red, a symbol of my sanguine attachment.

The stockings cannot be much larger than my own feet. I dislike large-footed gentlemen.

18th—My uncle asked if my great work of poetical inspiration was completed.

“Uncle, I haven’t written a dozen lines yet. My ‘Lotos Eaters’ is to be equal in length to ‘The Lady of the Lake.’ Now, see, Oji San, mine has to be far superior to the laureate’s, not merely in quality, but in quantity as well. But I thought it was not the way of a sweet Japanese girl to plunder a garland from the old poet by writing in rivalry. Such a nice man Tennyson was!” I said.

I smiled and gazed on him slyly.

“So! You are very kind!” he jerked.

19th—I don’t think San Francisco is very far off now. Shall I step out of the ship and walk?

Has the “Belgic” coal enough? I wonder how the sensible steamer can be so slow!

Let the blank pages pass quickly! Let me come face to face with the new chapter—“America!”

The gray monotone of life makes me insane.