Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

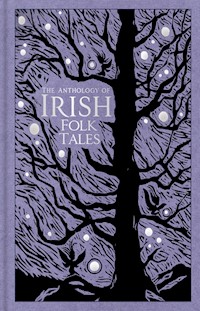

This enchanting collection of stories gathers together legends from across Ireland in one special volume. Drawn from The History Press' popular Folk Tales series, herein lies a treasure trove of tales from a wealth of talented storytellers. From fairies, giants and vampires to changelings and witches, this book celebrates the distinct character of Ireland's different customs, beliefs and dialects, and is a treat for all who enjoy a well-told story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 528

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© The Authors, 2020

The right of The Authors to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9460 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Europe

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

This book is dedicated to the three storytellers who are sadly no longer with us, but whose stories live on: Brendan Nolan, Jack Sheehan, Anne Farrell

1 DERRY

The Legend of Abhartach, the Irish Vampire

Amelia Earhart’s First Solo Trans-Atlantic Flight

2 ANTRIM

The Changeling

Someone for Everyone

3 TYRONE

Half-Hung McNaughton

The Tailor and the Witch

4 ARMAGH

Sally Hill

The Green Lady’s

5 DOWN

The Haunted Bridge

Maggie’s Leap

6 FERMANAGH

Wee Meg Barnileg and the Fairies

Return to Tempo

7 DONEGAL

The Silkie Seal

Salty Butter

8 LEITRIM

An Dobharchú

The Eggshell Brew that Unhinged an Imposter

9 CAVAN

Finn MacCool’s Fingers

The Nine Yew Trees of Derrylane

10 MONAGHAN

The Tale of Cricket McKenna

St Davnet

11 MAYO

The Love Flower

Tír na nÓg: The Land of Eternal Youth

12 SLIGO

Cormac Mac Airt

The Enchanted Cave of Kesh Corann

13 ROSCOMMON

Two Rocks

One Christian Account

14 LONGFORD

The Wooing of Étaín

15 MEATH

Gates That Won’t Stay Closed

The Black Pig’s Dyke

16 LOUTH

King Brian Boru’s Talkative Toes

Moyry Castle’s Killer Cat

17 WESTMEATH

The Sluagh Sidhe

18 GALWAY

Giant Love

The City Beneath the Waves

19 OFFALY

Messin’ with the Wee Folk

20 KILDARE

The Wizard Earl of Kildare

The Gubbawn Seer

21 DUBLIN

Two Mammies and a Pope

Wakes and Headless Coachmen

22 CLARE

Biddy Early and her Blue Bottle

Mal and Cuchulainn

23 TIPPERARY

The First Ever Brogue Maker

The Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch

24 LAOIS

Fionn MacCumhaill and the House of Death

The Bacach Rua

25 WICKLOW

Not Gone and Not Forgotten

The Resurrection of Sean

26 CARLOW

Story of a Pony

Labhraidh Loingsigh

27 KILKENNY

The Legend of Grennan Castle

The Story of Dame Alice Kyteler

28 WEXFORD

Treasures of Wexford

Hurling Days at Lough Cullen

29 WATERFORD

Slabhra na Fírinne – The Chain of Truth

Aoife and Strongbow

30 LIMERICK

Gearóid Iarla

Love You Large, Love You Small

31 KERRY

The Wizard Prince of Ross Castle

The Origin of the Killarney Lakes

32 CORK

The Legend of the Lough

The Mermaid from Mizen Head

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

THE LEGEND OF ABHARTACH, THE IRISH VAMPIRE

Long, long ago, the chieftains in Ireland fought against each other their whole lives and there was much bad blood. They fought over what god was best, they fought over the best land, and they even had mighty wars over women. In fact, there were very few things that they didn’t have a skirmish or a war over. But when the following tale was told by the bards to the chieftains of Ulster they all came to the same conclusion when they heard it, that there are evil beings around and they have ‘the Bad Blood’.

Now if ‘bad blood’ is translated into Irish it becomes ‘droch fhola’ and it is pronounced drocula, which is but a hair’s breath away from Dracula. You can ask yourself if it’s possible that Bram Stoker, who studied in Ireland, might have heard the legend of Abhartach and that this inspired him to write his story of Dracula.

It was well known in the country around Glenuilin, the glen of the eagle, in an isolated and remote townland in County Derry called Slaghtaverty, that there was a monument described as Abhartach’s Sepulchre, although the people around call it the Giant’s Cave. A lone thorn tree would guide you to it, but when you’d arrive you would see that no grass or vegetation grew there and an enormous heavy stone lay over the grave. If you happened to pass by you would be wanting to know who or what was Abhartach, and here’s the story you would hear from the locals.

Legend says that in the fifth century there was a poet who had a son whom he called Abhartach. That was a nickname for a dwarf because that’s what the child was, and it comes from the Irish, Abhac. But wouldn’t you think that the son of a poet would be a kind and gentle creature? Well, you’d be wrong about this one for he was a brutal warlord who lived in a hill fort, and from there he went out to petrify his people. So evil was he that his terrified subjects got rid of him, but sure didn’t he come back to wreck havoc and vengeance among them?

Some say that he was a wizard, a magician and a villain, but he was more than that, for although he was dwarfish in stature it didn’t stop him being one of the most cruel beings ever encountered in this land. People were scared witless of meeting this strange, wee man on the road or in the fields, for, being a magician, he could turn himself into any sort of an animal and could even become invisible if he had a mind to. Many a one hearing a strange noise turned around and found he’d appeared out of nowhere, and he didn’t hesitate to beat the life out of anyone who got in his way. Even after death no corpse was safe, because it was rumoured that he sucked the blood out of his victims and flung their bodies over his shoulder and fed them to the wolves, his only friends.

People tried to give him a wide berth as he ran amuck around the countryside on his vengeful rampage, usually under the cover of darkness. But eventually everyone meets their match and that match was a neighbouring chieftain by the name of Cathán, who was persuaded to do the deed for them. They wanted him to kill and bury Abhartach to rid their countryside of his evil presence. Cathán considered himself strong enough and fit enough to slay Abhartach, and he was fed up with the stories of the blood-sucking dwarf and the tales of his acts of cruelty on the innocent people of Slaghtaverty and the district about there.

Cathán was smart as well as strong, and he found out the place where this monster had his den. One night, when the moon was hidden behind the clouds, Cathán made his way to the covered ditch where Abhartach lay asleep. The ground was peaty and covered with thick moss, so the approach of the big man was as silent as the grave. He drew his iron sword and when he saw the mound of earth move he lifted his weapon high, and struck the mound with the full force of his body behind the blow. A horrific scream echoed over the hillside, and at that moment the moon emerged from behind the clouds.

Blood was seeping through the moss, and when Cathán pulled it away the face of Abhartach was exposed. It was a grotesque sight, with a mouth twisted in the most evil grimace that Cathán had ever seen. So bad was it that Cathán covered the face with his own cloak so that he wouldn’t have to look at it. He wrapped his belt around the body and with a heave that was no more than a featherweight to a man of Cathán’s stature, he flung the body over his shoulder and carried it to a rocky place to bury it.

Cathán went back to his own place, content in the knowledge that Abhartach would never terrorise the countryside again, or so he thought. But sure, he’d forgotten the belief of the ancients that if a person is buried in the upright position, facing his enemies, then he will have even more power over them than he had when he was alive. Sure, those druids of ancient Ireland knew a thing or two for what do you think happened next?

I said that Abhartach was a magician as well, didn’t I? Well, didn’t the vanquished dwarf rise again the very next day and this time he brought a harp with him and lured the unwary with sweet music. As soon as he had them in his grasp he was back to his old carry-on of demanding a bowl of blood from the veins of his victims to feed his evil corpse. What could Cathán do but come back to hunt him down?

Now, Abhartach had learnt a few lessons from his first death. He was not going to be so easily found. He went across the hills and searched until he found a cave. The entrance was so small that only a man the size of himself could slide in. He gathered a few rocks and pulled them across the small opening and contentedly fell asleep.

By night he waited for any living creature that dared to be abroad. It made no difference to him if his victim was man or beast, although he declared to himself that there was nothing sweeter than a young maiden, and these he wooed with his music. His appetite for blood became insatiable as the nights wore on and he began to be a bit careless. This was what Cathán was hoping for. The people of the area no longer went out at night; they locked up their animals in their barns and their families in their houses, for they certainly weren’t going to take any chances.

Cathán needed to draw Abhartach out if he was to kill him, so he conversed with his trusty Irish wolfhound and asked him if he would be willing to act as bait. His dog trusted him implicitly and Cathán whispered the instructions to him. He still had the cloak that he had wrapped around the dwarf the first time, so the dog got the scent and set off at a rare pace. Cathán, for all his large size, was fleet of foot, and within a short time the wolfhound came panting back to his master.

One of the things you should know about Cathán is that he had a great understanding and empathy with animals. There was not an animal that he couldn’t converse with, so when his hound told him where Abhartach was, he wasted no time. Again he approached quietly, wanting to catch Abhartach unawares, but he saw that the entrance to the cave was too small. He determined that he would wait for the monster to come out. His eyelids began to droop and, although he valiantly tried to stay awake, he began to dream of the lovely woman whom he hoped to make his wife. He settled into a beautiful dream and contentedly snored, forgetting all about his mission. But where would a man be without his dog?

Just before the first rays of sun crept over the hill the wolfhound’s ears pricked up and he let out a low growl deep in his throat, loud enough to wake his master. Cathán realised then that Abhartach was not in the cave, but had been out on the hunt for more blood. He sent the hound into the cave and hid himself behind a gorse bush. Abhartach made terrible guttural noises as he approached, and it was clear that he had not had a successful night’s hunting. He hunkered into the cave and the last thing he expected was that he would be grabbed about the throat by sharper teeth than his own. The dwarf managed to slide out of the cave while still trying to hold back the hound intent on ripping his throat apart. As his hand reached to his knife sheath, Cathán cleaved him at the back of the neck and killed him. Like before, he wrapped him in his cloak and carried him to a windswept part of the mountain to bury him a second time. But this time he piled more rocks high on top of the grave.

Would you believe it, but the bold Abhartach rose again and escaped from the grave, throwing the rocks to one side? No one to this day knows how he managed it, but manage it he did. He set about a more bizarre reign of terror, changing from one form to another, and those he caught he used them more cruelly and viciously than before, for the killings and burials had inflated his temper and his appetite for blood was loathsome.

Cathán, tired of the whole thing, decided that he would take some advice as to how he could kill Abhartach and bury him in such a way that he wouldn’t rise again. He went to a druid and asked his advice on how to vanquish this tyrant. The druid took the cloak that Abhartach had been wrapped in and swung it around seven times before he spoke, ‘The one you seek to kill is not really alive, he is one of the neamh-mairbh, or walking dead, and the only way he can be safely restrained is this; leave aside your sword of iron and fashion one of yew wood. Drive it into the heart of this monster. Then you must bury him upside down. This will teach his followers a lesson, for I have read the signs and there are many walking dead waiting for him to rise. Let Abhartach be buried upside down, for this is the rite that will deprive him of a restful afterlife. Fill his grave with rocks and clay, place a boulder atop and encircle it with a ring of thorns. In this way he will be imprisoned by the fairy folk, for should the stone be lifted Abhartach will arise.’

Cathán thanked the druid and on the way home cut a thick branch from a yew tree. All the next day he whittled it into a sword and tested it on a rock. It was surprisingly strong. Cathán was ready, and decided to tackle the monster head-on, armed with the sword.

His wolfhound led him to the new abode, a rocky inlet on Lough Neagh where Abhartach had made his home. He swam through the waters and spoke to the eels there. They understood what they were asked to do. They slithered into the inlet and wound themselves tightly around Abhartach’s neck and tightened their living noose until he was nearly dead. Cathán raised the yew sword high, then plunged it with all his might into the heart of Abhartach. He carried his lifeless body to the place now known as Slaghtaverty and buried him upside down with his head closer to hell, as the druid had said. He searched and found a huge stone and placed it over the gravestones and encircled the grave with hawthorns.

That was the third time Abhartach was killed, and he rose no more, for hadn’t Cathán asked the fairies to watch over it? And it is said that the reason the ground is raw and clear of plant life is that the Giant’s Grave is cursed ground.

Never again did Abhartach terrorise the people of Slaghtaverty.

N.B. The land on which the Giant’s Grave lies has a reputation of being ‘bad ground’.

Some years ago, when workmen were clearing the site, they had several unexplained accidents involving a chainsaw. They were attempting to cut down the tree, but the saw stopped dead without explanation, but when it was removed from the site it started working again.

There were attempts made to lift the heavy boulder but again, a strong iron chain snapped, hurting one of the workers, and when his blood spilled on the ground the earth seemed to heave and give a sigh.

Were these just pure accidents or was Abhartach attempting to show that his magic powers had still survived into the twentieth century?

AMELIA EARHART’S FIRST SOLO TRANS-ATLANTIC FLIGHT

On 21 May 1936, a strange sound was heard over the city of Derry. The clouds were fairly thick but scattered and the sunshine managed to shine through in parts, but at first the cause of the drone wasn’t seen. People in the Pennyburn area of the city came out of their houses and watched, shading their eyes as they looked up.

It was no wonder they were shocked, for as they watched they saw a small plane descend beneath the cloud cover. Rarely did they ever see a plane in the sky, never mind over Derry. As they watched it sink ever lower in the sky some made the sign of the cross, others stood with their hands over their mouths in amazement that quickly turned to consternation as the plane dipped out of sight over Ballyarnett. When it vanished they waited to hear the boom of a crash but there was only silence. They looked at each other, and, not waiting to put on a coat or scarf, there was a mad rush up the Racecourse Road to see what had happened.

At the same time James McGeady and Dan McCallion were standing in McGeady’s field in Ballyarnett when they heard the drone, and they couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw the plane clip the top of the trees bordering the next field. They too waited for the sound of a crash landing but the only sound was the putt putting of an engine, then silence as the engine went dead.

They ran across the field. Neither gorse bushes nor fences deterred them. Only when they spied the plane did they stop and look at each other, not sure if their eyes were playing tricks. The two men had never set eyes on a plane so close up before. Wondering what on earth it was doing landing in Gallagher’s field, they began to run towards it, leaping over the last fence.

As they approached, the cockpit cover slid open and the pilot stepped out. It was only when she took off her helmet and brushed her fingers through her thick, short hair that they realised it was a woman. By the time she descended quite a breathless crowd had gathered to see this unusual sight. There was great excitement as people pushed closer to have a look.

James McGeady, trying to look nonchalant, lit up a cigarette and stood beside the cockpit, whereupon Amelia Earhart, for that’s who the pilot was, turned to him and asked him to extinguish it quickly because there was a leak in the petrol tank.

‘Where am I?’ she asked, looking around.

‘You’re in Gallagher’s field,’ was the answer.

For some reason there was a photographer from the Daily Sketch on hand, and he had the scoop of the season, catching the moment after Amelia landed the plane. A young boy, Patrick Lynch, and the lady pilot were photographed looking straight at the camera and sure, that boy fed on that story till he was man big, and why wouldn’t he?

As Amelia walked with the men to Hugh McLaughlin’s house nearby they plied her with questions which she answered with good humour. She must have been exhausted, considering that she had just completed a transatlantic flight, never mind it being the first solo flight by a woman across that wide ocean. She had set off the day before from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland and hadn’t had a wink of sleep since then.

After some food and answering questions for a few hours, Mr Gallagher invited her to stay in his house in Springtown. She was glad of the offer for, although people didn’t really know about jet-lag then, that’s not to say she didn’t suffer from it. Although the mayor offered her deluxe accommodation in the best hotel in Derry she refused, preferring to stay in the Gallagher’s home in Springtown for a few days. She was feted in the city wherever she made an appearance. Boys-o-Boys, never were there so many photographs taken, and the news spread all around the world and brought glory on Derry.

Hundreds of telegrams, tributes, and accolades poured in for this brave woman who had completed a journey that many men believed a woman could not do. After that 1932 solo flight, women in the United States and throughout the world claimed Amelia Earhart’s triumph as one for womanhood. At a White House ceremony honouring her flight, she said, ‘I shall be happy if my small exploit has drawn attention to the fact that women are flying too.’

Amelia was a Kansas girl, born in Atchinson in 1896. As a teenager she worked as a military nurse in Canada and became fascinated by the stories of the early aviators. While she was doing social work in Boston she heard of a Trimotor plane being prepared to fly from Newfoundland to Britain. She applied for and was accepted as a passenger in 1926 on the plane Friendship, and in so doing Amelia became the first woman ever to make a transatlantic flight.

She met and married George Putnam, and he was happy that she wanted to go on with her flying career, even accepting that she wanted to retain her maiden name. His support didn’t stop at that, for he financed many of her flights across the United States after her solo flight to Ireland. It was just as well that he was a man with money, because flying in those days was an expensive and dangerous occupation.

Derry people kept a close eye on her exploits through the newspapers and indeed, felt proprietorial about her. When she flew the first solo flight across the Pacific to Hawaii they were just as excited as the Hawaiian people she met on the islands in 1935. She was a great girl for setting the records for solo flights.

But her bravery and ambition was to be the death of her. In 1937 she set off with her navigator, Fred Noonan, to attempt the first around-the-world flight in a twin-engine Lockheed Electra. After completing two-thirds of their circumnavigation they set off for Howland Island in the Pacific, and that was the last anyone ever heard of them or the plane. Earhart’s sense of adventure knew no bounds and people hoped that the pair would reappear, having magically survived, but that was not to be.

Like all disappearances, myths have grown up around the vanished plane and its occupants, but no one knows for sure what happened. In that sense it fits in with the cult of Irish folklore, where we weave our own imaginings around the facts with the idea that a good story is worth embellishing with a few twists and turns.

Amelia Earhart’s emergency landing in Gallagher’s field has already earned its place in Derry folklore.

There is no way to adequately describe how staggeringly lovely the land and seascapes are around the glens and coast of Antrim. They are described in guidebooks and tourist information as being among Europe’s top sites of outstanding natural beauty, with some being of special scientific interest. The only thing to add is that this is the case in any season and that from any ten minutes to the next, shifts in the light will dramatically alter the view and nature of the landscape. Quite simply, it is a magical, must-see area, enriching for mind, heart, soul and spirit. Little wonder that it inspires artists, notables being ‘true glensman’ Charles McAuley (1910-2000), acclaimed for his figurative, landscape and traditional works, and the contemporary artist Greg Moore, who depicts rural scenes and locations in pastels, watercolour and acrylic. He provided the beautiful illustrations for the book North Antrim: Seven Towers to Nine Glens.

Some may also find inspiration and childlike awe in the stories that exist side by side with the historical, geographical and geological facts of the glens. These tales of smaller races assert themselves as obstinately and blatantly as the distinctive features of the volcanic causeway rock itself.

Once, around the fertile soil of Glenarm and Glencloy, flax grew in a beautiful pale blue profusion. All the work on the crop was done by hand and none of it was easy. The land had to be finely tilled for the seed to grow. Then, in mid-August, after reaching around a metre high, the back-breaking work of harvesting commenced, with all members of the family involved. The flax was pulled from the ground in sheaths, called beets. Two or three of these were bound around in rush bands and the bigger bundles were known as stooks. With a cart piled high, the stooks were taken to a field for women to spread them out to dry, at which time the seeds would be removed and either retained for the following year, or used in animal feed.

Once the flax was dried and deseeded, it was loaded back on the cart, taken to a shallow pond or dam (sometimes referred to as the ‘lint dam’) and put into the water, head down. This was men’s work as it could get wet and cold when they carried on into the evening, and the stooks had to be weighed down with rocks and stones, as heavy as could be carried. This part of the process was known as retting and was aimed at rotting the woody covering of the plant, to expose the fibrous core. The decomposition produced an intensely strong odour, which made the removal of the stooks from the water after ten days most unpleasant.

Traditional music provided motivation and social respite during harvest time. Lint dam dances went on and the strains that certain musicians in the area played, particularly the fiddlers, had additional potency, as the ‘gentle folk’ taught them all the best tunes. There is, in these regions, a familiarity with these little types, variously called little folk, gintry, grogans, wee folk, the quality and other terms, but hardly ever are they directly referred to as fairies. It does not afford them the correct level of gravitas. A famous Kerry storyteller, scholar, author and broadcaster, Eddie Lenihan, sometimes refers to the beings as ‘them uns’, or ‘the other crowd’. The lives of poor, hardworking tenant farmers were literally reliant on their crops and livestock. They were hardly likely to put their belief and trust in fanciful, sweet, diminutive creatures with rainbow gossamer wings. As Noel Williams puts it in his essay in the book The Good People: ‘The notion of fairy in its earliest uses is not primarily to denote creatures, but a quality of phenomena or events which may or may not be associated with creatures.’

Each glen is unique. Glenarm is synonymous with rugged bogland, forests of wild flowers, salmon fishing and Glenarm Castle, home to the Earls of Antrim for 400 years. Glencloy is small and wide, and characterised by stone ditches. Archaeological digs in Glencloy revealed Neolithic (4000 BC) and Bronze Age (2000-1500 BC) settlements. Doonan Fort, an earthen mound, is Norman. At the foot of Glencloy is the seventeenth-century fishing village of Carnlough. A coaching inn built in 1848 has connections with Winston Churchill. It now stands as the Londonderry Arms, but was built by Churchill’s great-grandmother, Frances Anne Tempest, the Marchioness of Londonderry. He inherited the building, which he sold to the Lyons family. It was used for the rest and recuperation of soldiers during the Second World War and sold to its present owners, the O’Neills, some sixty years ago.

Glenariff is the queen of the glens. Thackeray is sometimes misquoted as describing it as ‘Switzerland in miniature’, but that is a phrase he saw in a guidebook. His own comment was: ‘The writer’s enthusiasm regarding this tract of country is quite warranted, nor can any praise in admiration of it be too high.’

Between Glenariff and Glenballyeamon, the flat-topped Lurigethan (often simply called Lurig) mountain rises from the heart of the glens, standing some 1,100ft above sea level and providing the most amazing backdrop to the beautiful village and townland of Cushendall. Basalt rock is evident along the top of its range, as well as an Iron Age settlement. Inland, along the A42 road between Ballymena and Cushendall, is the Glenariff Forest Park, with its stunning waterfalls.

From this particular area, many powerful stories have arisen. Little folk in their legions were seen, according to the directly recorded accounts in the Fairy Annals of 1859. Whole armies engaged in battle by land and sea. A blacksmith from the glens who had shod a grey horse for one of the gentle folk (reluctantly) on a Sabbath day, was later charged with the task of finding more grey horses for the wee man’s army. As proof of their existence, the blacksmith was shown row upon row of sleeping warriors. But it seems the gentle folk more often took a hand in domestic or agricultural matters. Here is a compilation of some adapted versions from The Fairy Annals of Ulster, No. 2.

THE CHANGELING

Tam’s mother knew Rosie’s family. They were the closest neighbours. One long hard winter she went to Rosie’s mother to ask for a little flour to tide her over and put a bite in the mouths of her large, young family. The tailor’s wife took some sort of fit of fierce pride and gave neither welcome nor flour. And it was not that she was short.

That sort of thing would never be forgotten, and there was a lot more to a refusal like that than meets the eye in the glens. The wee folk could help people, but, as they took a hand in the fortunes of the crops and livestock, they were not best pleased when the resources were not shared in times of hardship. It is never advisable to be mean.

Rosie was the second oldest of the tailor’s children. Unlike her mother, she was as kind-hearted as she was pretty and never a complaint. She nursed all the younger children in the family and was most fond of baby John. She put light in his eyes from laughing and soothed him to sleep with just a bar of her sweet song while she was spinning yarn.

The baby was not the only person beguiled by Rosie and, in time, she and Tam were courting. Tam’s mother and father were not entirely happy, as they feared Rosie might turn proud, scowling and mean like her mother. So Rosie had a job keeping everyone happy.

Tam asked the girl to spin some yarn for him to sell at market, that they might be married all the sooner. Indeed there was no one better for spinning, but for some reason, whenever Rosie tried to spin the yarn for Tam, things went wrong and her wheel broke.

Her father thought to mend the wheel for her, and as he worked at it she took baby John on her hip and out into the yard, singing him a wee song. She was walking around the cottage, when the child gurgled and reached for an old clay pot sitting on a window sill. The pot fell and smashed, and where it had been was a pile of silver coins. Rosie stood, shocked at the find. She thought it might help her and Tam with the cost of the marriage, and she might even get a brand new spinning wheel too. She went in to tell her father about the silver. When he came to look, there was nothing but the smashed pot on the ground and some hawthorn leaves on the sill.

It is said that if ever the wee folk make a gift, it should be taken in the spirit it is given: anonymously. Rosie was mighty downhearted and tried to settle John in his crib, but he clung to her more than ever before and started to shriek and shriek in a high-pitched cry. When she got him into his cot, she hardly knew the child looking back at her. He was pale and cross and looked through her, as if she was a stranger, before starting up his piercing cries again. The noise brought Rosie’s mother. She had been working at the girl’s wedding gown and told her to go and look at it.

While Rosie was off admiring her beautiful dress, her mother could not settle baby John at all. When Tam came to try on the wedding suit that the tailor had made for him, he could not believe the noise when they left him alone in the room where the baby was. No sooner was the door closed, the ugly changeling, for that’s what the baby had become, leapt from the cot, asking Tam, ‘Where did that mean old hag go?’

The hair stood up on Tam’s head. He grabbed the suit and took to his heels.

When Rosie’s mother and father returned, Tam was gone, but the being had produced a set of pipes and was whirling around the room. The tailor and his wife were distraught. They captured the wee man in a sack, intending to drown him, but he was strong and struggled. They fell carrying him and he ran free, laughing.

Such sadness as fell on that house was never known. Rosie was heart-sore at the loss of baby John, but she had lost her true love Tam as well. He never wanted to set foot in such a house again and took himself off to Scotland.

So one evening, blinded by tears, Rosie sat sobbing by little John’s cot and saw something under the corner of the blanket. She pulled back the cover and there were the silver coins. She gathered them with a mind to use them to go to Scotland and marry Tam. She quickly pulled on her bonnet and shawl and left the house; no one knew of her going, and in the weeks following, no enquiries could reveal where she was.

It was some months after, at Hallows Eve, that Rosie’s eldest brother was returning home in the dark. He was coming along the road up from Cushendall on his horse. From behind him, a tumultuous noise arose and he was caught, as if in the midst of a stampede, as troops – thousands in number – rode for Tiveragh Hill. He was terrified. The din was deafening, and his eyes could not adjust to take in every figure rushing by. Yet in the midst of it, he thought he could hear a woman’s voice repeating, over and over, ‘Fetch me the wedding dress; fetch me the wedding dress.’

It was the boy’s wish to find his sister and bring her home safely to her parents, so he slipped into the house and got the gown without anyone knowing and brought it back, laying it under the skeogh (fairy thorn) up on the hill. He was careful not to touch or disturb the tree, as all in the area knew that wherever such a tree grows, no matter if it is in the middle of a field, or grazing ground, it must never be cut down or uprooted. Ploughing, seeding and harvesting may go on around it, but the stories of vengeance that the wee folk take if the skeogh is harmed was enough warning for most. The curse could be loss of speech, long bouts (sometimes years) of degenerative fever, paralysis, blindness, and there is even an account of someone’s head being turned the wrong way on his shoulders.

So Rosie’s brother walked cautiously away from the tree. When he turned back, his sister stood dazzling in her wedding clothes, with little John gurgling happily on her hip. She told him that without the dress he would not have seen her, but warned him to keep his distance, as the hillside opened on a huge party. Every kind of mouth-watering food and drink was there and the best music, dance, song and storytelling he had ever heard. Again, Rosie warned her brother to keep his distance and not to eat or drink with the company, and never to speak of their meeting, otherwise he would join them forever.

In the morning, he was listening to the sweet song Rosie sang to get baby John to sleep. He suddenly realised he was lying with his ear to the ground. When he sat up, there was nothing but Tiveragh Hill and its fairy thorn.

SOMEONE FOR EVERYONE

There was a time when a fella might meet and court a girl in all kinds of ways. Ballycarry was known as the original home of Presbyterianism in Ireland, and that would have helped and hindered love and romance in equal measure. Choirs, village services, guest teas, Church socials and soirées, as they are known, might all have thrown couples together.

The soirées were said to be an assembly of the finest talent that any could level an insult at. Willie Hume (Billy Teare’s grandfather) was a stalwart. They were actually great craic, with recitations, storytelling, singing and music, and all of it good-natured. Not staged events or anything like that.

Then there were markets and fairs and proper tradesmen selling their goods. The old villagers would remember the blacksmith shop, standing at the top of Fair Hill, and the two saddler’s shops in the village. There was a cooper’s shop at Hillhead, or Barronstown, to give it the original name. A draper’s shop, shoemakers, dressmakers, carpenters, spinning and weaving, tailoring, crochet, lacework, and a thing called ‘flowering’ (which was a type of local embroidery) all created industry for Ballycarry. You need hardly have gone outside the village for anything. So with the churches, the gatherings, and all the skilled men and women, there had to be someone for everyone.

Well there was one girl, Maggie, and she was short of admirers. All the usual avenues were exhausted, along with any man she had ever set her cap at. She had even tried the pin well in Redhall. She knew about it from childhood. At the point where a stream had cut its way through chalk to the foot of the old Mill Glen, that is where the pin well could be found. There is no written reference as to how the custom came about, but endless people have visited the little well, to drink the water and drop in a pin in order to make a wish. It must have been that the sprites, spirits or ‘kelpies’ – or whatever else has been said to grant people’s desires – were not at home when Maggie dropped her pin in.

You would have thought that might be an end to her listening to old superstitions and stories, but no. She lapped up the rites and rituals that were well known in the area. Right enough it is a bit of a puzzle that God-fearing folk would also harbour pagan beliefs, but country people, living cheek by jowl with nature, could often see nature behave in an altogether unnatural way, so some odd views persisted.

Seasons bring with them opportunities to foretell a person’s luck in life and love. None more so than Halloween. At that time, all kinds of things become a means for prediction. Fitting with the spooky activities, country girls might have used apple peels, or gazed in mirrors by candlelight, to find out who their future partner might be.

One thing that was supposed to guarantee a husband was to procure a shirt from your intended. (One would guess that if you were that familiar, you would already be in with a fair shot at marriage.) Then, at midnight on Halloween, his shirt was to be washed with her … unmentionables … and dried before an open fire.

Now, Alexander was one of the only bachelors left in the area and that had not escaped Maggie’s notice. But he was a boy completely impervious to her attempts to allure him. Every time he would pass by, she would try to have him catch her in the act of knitting, or quilting, or flowering, to show herself as a skilled lady and so worthy of marital selection. Then, she would occasionally slip him oatcake, or roozal fadge, skink-lerrie, or brose. The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, but who could fathom the way to the heart that lay in the lad of Maggie’s dreams?

So then, no one was more surprised than Maggie when it was coming to Halloween and she got a visit from Alexander’s mother. It seems that as much as Maggie wanted to take him as a husband, the mother was keener for him to take a wife. The hoping and wishing had not worked, so his mother had decided to give things a firm boot in the right direction and delivered one of his shirts to Maggie. Eyeing Maggie, she shuddered at what ‘unmentionables’ might be washed with the shirt, but it was clear to her that Maggie was a practical lady of many skills, and sometimes a pot to pee in is more use than a vase for roses.

Maggie thought her heart would never last out until Halloween, when she could get her washing done and drying. But eventually the day arrived and the task was complete, and there she sat, staring into the steam rising from the newly laundered items, dreaming of being Alexander’s wife. She thought of the bridal garb, bouquets, and wedding breakfasts, and she hardly noticed when, on the stroke of midnight, there came a dunnering on the cottage door. She roused herself, smoothing her dress and sweeping stray hairs behind her ears, preparing for the man of her dreams, Alexander. She was VERY shocked to open the door to … the itinerant worker, Cosh-a-Day!

Cosh-a-Day passed straight by her, heading to the heat of the fire. He sat, babbling about his work, hedging, ditching and farming with Alexander and his mother.

‘Huh, Maggie, all was weel with Sandy and the mither, until a shirt went missing and he said I stole it and threw me oot the …’

Cosh-a-Day trailed off. First there was the sight of an enormous pair of bloomers, stitched up and down with every kind of lace, trim and ribbon. That was bad enough. But when he caught sight of the stolen shirt, drying before the fire, he immediately knew he must be in the house of a hussie, or a thief, or both, and he tried to make his excuses and leave. Hearing all this and following his gaze, Maggie also understood what he was thinking and wanted to cover up her intentions; she thought that if she confessed what was really happening, the charm might not work. So quickly, she offered him a place to stay.

‘It’s ill on you. Never worry about that stuck-up lot. They came from Whitehead and aren’t they all pride, poverty and pianos? You’ll be wanting a stay in the barn tonight?’

As Cosh-a-Day hurried for the door, he said, ‘No thanks Maggie.’ And in his words she felt the weight of his disappointment in her. ‘I’ll tak mesel’ to the barn of daycent folk if you don’t mind.’

Maggie was mortified, until the hapless Cosh-a-Day remembered why he had called to see her and left her with a parting message. ‘Oh, by the way, before he threw me oot, that gulpin’ Sandy sayed to tell ye he’ll ca’ in for a bite to ate with ye the marra nicht.’ He cast his eye back to the steaming garments. ‘You’ll maybe hae the shirt on the claes prap dry be then.’

Well Cosh-a-Day held his tongue and never spoke about what he had seen, and Maggie and Alexander were married. Cosh-a-Day avoided Maggie and wondered how Alexander would get on with her.

When Maggie was married, her mother-in-law gave her the gift of a shawl. It was made from an exquisite yarn from Mossley Mill and trimmed with a rare lace, made by the Single Sisters Choir House, from the Moravian settlement in Gracehill. The flowering of this community was known to be worn by nobility, and Maggie succumbed to the sin of pride. She took herself further and further afield – anywhere that a woman could think to go – in order to brag of her new fine husband and show off her fine, expensive shawl.

This was all well and good, but in those days a working man did not expect to come home and start making his own dinner, and Maggie’s wandering and boasting was starting to get the better of Alexander.

So he came home to an empty house, no fire or food, for yet another evening and, after making himself a feed of bread, cold ham and cheese, he stomped his bad mood and mutterings to the oul’ wa’s, to give his head some peace – and there was Cosh-a-Day. It was no surprise to him to hear how things were working out with Maggie. He wanted to make things right with Alexander after the misunderstanding about the stolen shirt and said, ‘Dinna fash yersel’ Sandy, I’ll ca’ in to see her mesel’ the marra and see if I cannay get some reasoning aboot her.’

Well Alexander was not best confident in entrusting this task to Cosh-a-Day, but something had to be done.

The next day, Cosh-a-Day found Maggie in a state of dread. He could not get a word in about the purpose of his visit: her gadding around visiting this one and the next to brag about her hubby, and yet leaving him starving by the cold hearth. It seems Maggie was waiting on a visit from one of the in-laws, and a worse old scold, or better example of a dour Ulster Scot, there never was. Her mother-in-law’s sister, Mrs McKee, had made it clear how little she saw in Maggie on the day of the wedding. This being her first visit, Maggie wanted to make a good impression, but feared that no matter what she did, Mrs McKee would find fault. Maggie became so fraught that she beseeched Cosh-a-Day to say she had gone somewhere.

‘Right oh,’ said Cosh-a-Day cheerily. ‘I’ll let her know you’ve gone Maggie. Ye go hide yersel’ girl.’

Maggie had no sooner stepped into the next room, than Cosh-a-Day was helping Mrs McKee (but mostly himself) to the grand spread Maggie had left. Mrs McKee sat bolt upright, in a large fancy hat.

Cosh-a-Day started, ‘Aye, ’tis a brave lot of food was left after the funeral. Get stuck in Mrs McKee.’

‘Funeral?’ said the startled visitor.

‘Och now, Mrs McKee, ye are no’ goin’ tae sit wi’ that face on ye, unner such a hat and tell us ye never heard that poor Maggie, only newly married, wi’ a grand shawl and aa’, had left us?’

Well, the old woman was shocked to the very core as Cosh-a-Day went on, knowing full well that Maggie would be listening at the door.

‘Faith aye. She was a lovely woman Maggie, but I am sure a discerning lady like yoursel’ would a knowed she was lucky enough, no disrespect to her, to snare Sandy.’

‘Well, yes,’ agreed Mrs McKee. ‘At the ceremonies, I have to say I did notice she was a little … plain.’

‘Plain is it?’ said Cosh-a-Day. ‘I seed better looking cows when they was heading awa’ frae us. And I can tell ye, she didna wait for yon fella as that white dress mighta sayed. I was in her hoos yin nicht, BEFORE they were wed ye understan’, and she’d his shirt and a pair of … well, washing that a unmarried woman disnay wash wi’ a man’s things, drying awa’ for all to see.’

Maggie winced from biting her tongue in the next room.

‘What was that noise?’ the old lady asked.

‘Och, ye know I hae been wunnering that mesel’. ’Tis the room she ‘went’ in and I am no’ sure, but … no, no, it’s probably just the wyn.’

Mrs McKee was reassured and went on. ‘What you say about Maggie’s dubious nature is no surprise. I have been hearing all kinds since the wedding. Apparently she was bone idle and never home keeping house. Her poor husband never got a cooked meal, morning, noon, or night.’

Maggie was hopping with rage and all kinds of snorts and groans came from the next room.

‘That really is a FRIGHFUL draughty room,’ said Mrs McKee.

‘Aye, I will awa’ tae fix it up just noo,’ said Cosh-a-Day. ‘But before I go, I should tell ye, ye bein’ a lady that’s never had a doobroouss nature in her life. Just before passing, Maggie had a great change o’ heart. She stapped her rambling and boastin’ and do ye know Mrs McKee, she said ye brought aboot that change. Ye spoke so straight aboot her shortcomin’s, ye made her a better person and she left ye this …’

Maggie creaked open the door a little and saw Cosh-a-Day giving away her shawl. It was the last straw; she leapt from the cupboard and gave the old lady such a start, having seemingly risen from the dead, that Mrs McKee near passed out cold. Maggie snatched the shawl from her in-law and turned her out of the house, reddening her face with every insult of the day she could. When Mrs McKee was out of the way, she picked up the poker to hit Cosh-a-Day a crack, but he had long gone and he thought it had done Alexander a good turn and done Maggie not one bit of harm.

HALF-HUNG MCNAUGHTON

Thanks are due to Celia Ferguson (née Herdman) for telling me about how one of her ancestors was robbed by a highwayman and to Gabrielle Dooher for giving me information about Half-Hung McNaughton.

Half-Hung McNaughton belonged to a wealthy family. He had a good job working for the government as a tax collector but he also had an addiction to gambling. He lost all his own money and started gambling with the government’s money. He lost £800 of his employer’s cash (the equivalent of about £500,000 today) before disappearing from respectable society to become a highwayman and escape justice.

McNaughton had a very good friend, Andrew Knox, who owned Prehen House in Derry/Londonderry and had a beautiful, 15-year-old daughter called Mary Ann. She became besotted with McNaughton and wanted to marry him. Andrew Knox was very annoyed and forbade the match. He felt that there was too big an age gap between the couple (Mary Ann was only 15 while McNaughton was 39) and that McNaughton’s main motivation was to get his hands on her money so he could clear his debts and continue gambling. He decided the best thing he could do was take Mary Ann away and hope she’d forget about her lover. Unfortunately, the girl managed to contact McNaughton by leaving and receiving notes at a tree and he arranged to kidnap her.

McNaughton dressed in his highwayman gear and met the coach in which Mary Ann and her father were travelling. There was a fracas during which McNaughton accidentally shot and killed her. Both he and her father were wounded. He managed to escape but was eventually captured and incarcerated in Lifford jail before being tried. He was sentenced to death ‘by hanging on the great road between Strabane and Lifford’. He mounted the gallows and the hangman placed the rope around his neck and attempted to drop him to his death. The rope broke and McNaughton fell to the ground, unhurt. Anyone who survived hanging automatically received a pardon. He could have walked away a free man, but he did no such thing. He picked himself up, climbed back up onto the gallows and shouted, ‘I don’t want to be pardoned. I don’t want to be known as “Half-Hung McNaughton”. I don’t want to live without Mary Ann. I demand to be hung!’ He insisted the hangman’s rope be placed around his neck again and jumped off the gallows with such vigour that his neck was broken and he died instantly. His body was buried in St Patrick’s old graveyard in Strabane. His ghost is said to haunt the graveyard and the road between Strabane and Derry/Londonderry.

Half-Hung McNaughton was an unusual highwayman because nobody appeared to have any respect for him. In the past, taxes and rents were high, much higher than in England. Farmers existed on a knife edge. If they couldn’t pay their rent, they were evicted. Most highwaymen robbed from the rich and gave to the poor in the tradition of Robin Hood. They were regarded as folk heroes, protected by the local population. But McNaughton did not share his ill-gotten gains; he kept them. After his death the population split into two camps: those who felt sorry for him and believed he really did love Mary Ann Knox and committed suicide because he couldn’t bear to live without her and those who felt he committed suicide to avoid ending up in a debtors’ prison, which could have been regarded as a fate worse than death.

Celia Ferguson (née Herdman) told me about how one of her ancestors, a doctor called John Herdman, was robbed by a highwayman. One night when he was coming home after visiting a patient, he was attacked and stripped of everything except his shirt! Poor John Herdman was very embarrassed by his state of undress and went to the home of a local parson for help. The parson thought he was a ‘rogue and a vagabond’ and refused to let him in. John managed to prove he was an educated gentleman man by speaking in Latin. When the highwayman was caught and sentenced to death several years later he confessed on the gallows and apologised for treating John Herdman so badly.

THE TAILOR AND THE WITCH

Folklore is full of tales about witches who could shapeshift into humans or animals at will. Cows and hares are commonly thought of as animals that may be witches in disguise. Linda Ballard, who was working at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum at the time, shared this story about the witch and the tailor. I love telling it to children because they usually cannot resist looking for a patch of fur in their hair!

In the past, children who had difficulty walking often became tailors because they could earn a livelihood by sitting sewing. They travelled around the countryside with a list of clients they visited regularly, doing whatever task they were asked to do. If a coat, skirt, blouse or suit became shabby, the tailor could recycle it by carefully unpicking the seams, turning the garment inside out and sewing it up again, so it looked like new, or he would make new clothes out of cloth supplied to him by his client.

Once upon a time, there was a tailor who unknowingly went to work for a witch. She lived alone in a small, single-roomed cottage. Each night she slept in an offshoot bed beside the fire while he was given a straw-filled mattress in the half loft to sleep on. He had to sprockle up a ladder to get there. Once he was in position, he could peek over the edge of his sleeping quarters and see what was going on down in the room below.

One morning he woke up and sniffed the air. It felt strange, enchanted, somehow different from usual. There was no sign of any activity below. He guessed that the woman was still asleep so lay still and quiet, not wanting to disturb her. After a few minutes he heard the door being quietly opened. He peeped over the edge of the half loft and saw a huge hare come in, go over to a large barrel of water sitting in the centre of the floor and jump in. Within seconds the woman leapt out of it. The tailor couldn’t believe his eyes. He spent the whole day thinking about what he’d seen. Surely he must have been dreaming?

The next morning, he woke up very early, looked over the edge of the half loft and watched quietly. He didn’t have long to wait before the woman got out of bed, pulled the large barrel out into the middle of the room, filled it with water, walked three times round it, singing a strange eerie incantation, and jumped in. A large hare jumped out of the other side and disappeared through the door. The tailor thought it would be prudent to pretend to be asleep so he turned over onto his back and waited. Sure enough, the hare returned after about an hour, jumped into the water and out came the woman. The tailor could hardly sew that day because his mind was in such turmoil. Had he dreamt the same dream for two mornings in a row? Could the woman really turn into a hare? Was she a witch? There was something strange about her. Could she cast a spell on him? If she really did turn into a hare, where did she go in the mornings? Could he find out? What would happen if he jumped into the water? Would he turn into a hare? Could he follow her?

The tailor woke up very early next morning, determined to find out what was going on. He watched as the woman prepared the barrel of water, walked three times round it singing her strange, eerie incantation before jumping in and turning into a hare. He felt very excited as he stumbled down from the loft, jumped into the water, leapt out in the form of a hare and rushed out the door. He was just in time to see her disappear through a gap in the hedge. He followed her into a field and up a hill, at the top of which there was a flat piece of ground. When he reached the top, he saw that hundreds of hares were gathered there, so he joined them.

A large, white hare was standing in the middle of the assembly. The moment he arrived it stood upright on its back feet, sniffed the air and shouted, ‘There’s a stranger in our midst! Danger! We’d better scatter.’ The hares immediately turned tail and ran away in all directions. The tailor followed the one he guessed to be the woman. She ran into the cottage, jumped into the water, reappeared as the woman and he had just time to cover himself in water before she used her superhuman strength to empty the barrel. He returned to his normal self as the water flowed down the street outside her cottage.

The woman was raging. She howled fury at him. ‘What have you done?’ she shrieked. ‘Why can’t you mind your own business? I’ve a good mind to cast a spell on you.’

‘Oh, please don’t do that,’ pleaded the tailor. ‘I promise never to tell anyone what I saw. I’ll be as silent as the grave. Tell you what, I’ll gather my things and leave immediately. I’ve just about finished and you needn’t pay me for the work I’ve done.’

The woman glared at the tailor as he gathered his things together and headed out the door. He was terrified by the look she gave him and apologised as he staggered out the door. ‘Goodbye, m-m-ma’am. I’m very sorry to have offended you, m-m-ma’am. I promise I’ll never utter a word about what I’ve seen.’

‘One word of your experiences and you’ll DIE!’ screamed the woman.