Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

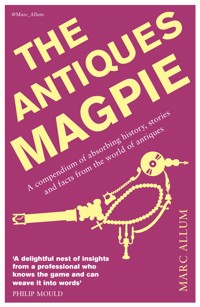

From the mythical artefacts of the ancient world to saucy seaside postcards, The Antiques Magpie explores the wonderful world of antiques and collectables. With Antiques Roadshow regular Marc Allum as your guide, go in search of stolen masterpieces, explore the first museums, learn the secrets of the forgers and brush up on your auction technique. Meet the garden gnome insured for £1 million, track down Napoleon's toothbrush, find out how to spot a corpse in a Victorian photograph – and much more. This book is for anyone who's ever been fascinated by what relics of the past tell us about history – and what they are worth today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also available from Icon Books

The Science Magpie

The Nature Magpie

Printed edition published in the UK in 2013 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

This electronic edition published in 2013 by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-184831-619-5 (ePub format)

Text copyright © 2013 Marc Allum

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typesetting by Marie Doherty

For Lisa and Tallulah

Only the curious find life a mystery

—Anon

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marc Allum is a freelance art and antiques writer, broadcaster, consultant and lecturer based in Wiltshire. He has been a miscellaneous specialist on the Antiques Roadshow since 1998 and has appeared on several other television and radio programmes. Marc spent sixteen years as a London-based auctioneer and has written and contributed to numerous books. He writes regularly for magazines and has a passion for playing the bass guitar and tinkering with large engines.

CONTENTS

Other titles in series

Title page

Copyright information

Dedication

About the author

Introduction

Mythical objects

The Antiques Roadshow: a national treasure

What’s in a name?

Napoleon’s penis

Coining it

A ghost story

Punch and Joan

Is it possible to die of nostalgia?

Drop-dead gorgeous

A history of -isms

Looking glass

The language of jewellery

Tretchikoff – king of kitsch?

A catalogue of errors

State of play

Ulfberhts, Chanel handbags, patents and copyright

Mermaids and sirens

Did Elgin steal the marbles?

What is Art Deco?

The Queen’s knickers

Treasure trove – the law

The life of a mudlark

Animal, vegetable or mineral?

Plastic fantastic

Image conscious

Comic book heroes

Merchandising mania

The death and burial of Cock Robin

Decoding art

Smash it up!

Warhol in a skip

Droit de suite

The first museums

Tradescant’s Ark

Metal guru

The gold standard

Tavernier’s Law

Dead and gone

In the face of death

Bullet point

Key man

Do girls like playing with trains?

Balls

À la Française or à la Russe?

Hard-paste or soft-paste?

Willow pattern

Crash mail

The value of courage

Top ten film posters

Star bores

Where is it?

Auction bidder

Stolen to order

Backstairs Billy

Helen of Troy

What’s a Grecian urn?

How to spot a fake

Tom’s time bombs

Charity case

Provenance is everything

A family business

Wooden puzzle

Five-clawed dragons

Poison chalice

Empire crunch

The Biddenden Maids

The rarity of cats

Branded

Fake or fortune found?

Step into history

Design icons

Luggage label

Etiquettes de vins

The president’s tipple

Hitler’s diaries

The Gang of Five

A complete monopoly

Card sharp

Cereal killer

The history of hallmarks

Heritage lottery

Ten a penny

Ooh-err missus

Vanitas

London Bridge is falling down

Lost Leonardo

1933 penny

Japanese dress sense

Swordplay

Cloisonné or champlevé?

Chinese whispers

Austerity measures

Gnome alone

Fake dinosaurs

Name check

Made to kill

Flag day

Clean me

Social worker

Acknowledgements

Appendix I: At a glance British and French monarchs

Appendix II: A brief guide to periods and styles

Bibliography

Also available in this series

INTRODUCTION

antique, n.

a collectable object such as a piece of furniture or work of art that has a high value because of its age and quality …

magpie, n. and adj.

B.adj. (attrib.)

1.Magpie-like: with allusion to the bird’s traditional reputation for acquisitiveness, curiosity, etc.; indiscriminate, eclectic, varied.

—Oxford English Dictionary

[Author’s note: In my opinion ‘high value’ is not a definitive reason for an object being of antique status.]

We are by nature acquisitive. We all collect. It’s not something that is always physically manifested in the sense of a stamp album or a collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. You can collect just about anything, even quite intangible things like thoughts. I can’t remember jokes but I have a friend who is a walking anthology. It’s all in his head; he’s a collector of humour.

Collecting is complicated, an infusion of many variables drawn from our fragility, insecurity and desire, driven by the need to leave a mark on the world, validate, educate and elucidate. For some, it simply complicates matters; we are, after all, just temporary custodians with a limited period of time with which to play out our acquisitive tendencies, unlike the great museums and institutions, which offer a comforting permanence.

I’ll try to keep it as real as possible but within these pages you’ll have to deal with various notions that might at first seem surprising. You thought that you were buying a book about antiques, and you are, but it’s all much more complicated than it first appears, mainly because what is tangible in the world of art and antiques is often just a physical manifestation of something far more ephemeral and more likely based on historical interpretations of religion, death, science and fashion. That’s why you’ll find some rather esoteric headings such as ‘Mythical Objects’ and ‘The First Museums’. These will hopefully help to put our (and by ‘our’ I’m referring to the human race as a whole) acquisitive habits and idiosyncratic accumulative tendencies into perspective.

We need history, it gives us a sense of worth, solid points of reference along which to place the milestones of time, a ledger of the lessons we continually fail to learn. These milestones are the buildings, the bones, the photographs, the middens, the flint arrowheads and the golf ball on the moon. We need memories, and these objects form the bridges in time that reinforce our ‘souvenirs’.

I started collecting as a youngster, probably around the age of nine. There was an innocence to the pursuit at that tender age, one that I miss. As you get older you acquire more and more emotional baggage, more life experience and it forces you to readdress the way you look at life and artefacts. This can be a trap for the serious collector, as mortality and objects are closely associated. As a boy, I would leave home on my bicycle, a spade strapped to the crossbar, cycle several miles and spend hours digging an old bottle dump. The dark, cinder-blackened earth that characterised 19th-century dumps belied the potential treasures that I eagerly sought: the Cods and Hamiltons (types of bottles) that I loaded into my father’s old canvas rucksack ready for the long slog home. I washed them in a plastic bowl in the garden, scoured off the rust stains and arranged them on shelves in my bedroom.

Now, it’s different. As I grew older, the objects began to acquire voices; they started to speak to me. The bottles were no longer inanimate objects fashioned from silica, sodium carbonate and lime. My desire to acquire objects with louder voices grew, and instead of mineral water and sauce bottles I wanted 18th-century claret bottles resplendent with seals. Now I wanted to know who had owned them. And there you have it; I had caught the disease that is antiques. There is no known cure.

Marc Allum, 2013

All art is useless.

—Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

MYTHICAL OBJECTS

Objects are what matter. Only they carry the evidence that throughout the centuries something really happened among human beings

—Claude Levi Strauss

It’s easy for us. With centuries of research and archaeology behind us, and with the marvellous resources of museums and institutions now at our disposal, we are to a great extent able to find out what most things are, or we at least have the foresight to save things for future generations to re-examine. We live for history and, consequently, history lives for us. That’s not to say that we aren’t constantly discovering new things about history and objects; it’s just that we have a great accumulated knowledge at our disposal.

Imagine when things were different and a person going about their everyday life – a 15th-century serf for example – had absolutely no idea what a fossil was. When your daily existence revolves around a few important precepts such as God, eating to stay alive and paying your tithes, it’s not difficult to see how your Christian view of the world might have been steadfastly instilled in your head to discount any notion of an alternative other than the sure-fire stone depictions of Purgatory and Hell carved around your local church door. So, what did the serf think a fossil was? It’s an idea that grew in my head many years ago, taking objects from prehistory and antiquity and trying to find out what people thought they were, as opposed to what we now know them to be.

As a consequence of this fascination, the ‘Enlightenment’ room in the British Museum is one of my favourite spaces in the entire world. Admittance should be strictly limited to people wearing 18th-century dress. Gazing at the wondrous objects in the cases is as close as it’s possible to come to the individuals who formed our understanding of the world and the objects in it. Here you can gaze upon Dr John Dee’s (1527–1608/9) obsidian mirror, an Aztec artefact used by the famous occultist and ‘consultant’ to Elizabeth I to summon spirits. Dee, like many intellectuals, tried to reconcile the divide between science and magic; these are some of the most enigmatic display cases in museum history and you too can absorb the energy of these powerful artefacts. The once-mythical status of these objects imbues them with a special meaning for collectors. Here are a few of my mythical favourites:

Unicorn’s horn

The unicorn, a legendary supernatural creature usually depicted in European mythology as a white horse with a long spiral horn emanating from its forehead, was the most important and idealised mythical creature of the Middle Ages. It could only be captured by a virgin and the horn, said to be made of a material called alicorn, was thought to have magical properties including the treatment of diseases and as an antidote to poison. As a result, ‘unicorns’ horns’ that appeared on the market had great value, and were fashioned into amulets, cups and medicinal preparations. However, we now know that these ‘horns’ were actually narwhal tusks. The narwhal is a species of whale that lives in Arctic waters. The tusk is in fact a tooth and in some rare cases a narwhal will grow two such teeth.

The ‘horns’ were of such high value that they were traded by Vikings and coveted by royalty, often taking the form of chalices that were used to divine poisoned drinks. The Imperial Treasury in Vienna has on display the imperial crown, orb and sceptre of Austria, the latter fashioned from a unicorn’s, or rather narwhal’s, horn. Objects fashioned from narwhal tusks were favourites among blue-blooded collectors and power-hungry despots – they were the most likely to be poisoned – and were the type of object essential to any cabinet of curiosities.

The myth of the unicorn continued to be believed well into the 18th century, although scholars had largely debunked the magical origins of the horns by the mid-17th century.

One famous representation of a unicorn was constructed by the mayor of Magdeburg, Germany, Otto von Guericke, in 1663. Like many towns needing an attraction, he bolstered tourism by constructing what he claimed to be a unicorn, from the fossilised bones of a prehistoric rhinoceros and mammoth found in a local cave. It’s still there to this day.

Much valued among collectors, an antique ‘unicorn’s horn’ can realise thousands but beware, narwhals are an endangered species and the trading of their mythical teeth is now governed by the CITES convention.

Hag stone

This is one for the low-budget collector and one of the first mythical objects I acquired; in fact, you can pick them up for free. A hag stone, also known as a witch stone, druid stone or sometimes adder stone, is basically a stone with a naturally occurring hole through it. They were and still are regarded by many as powerful amulets, although the idea that they are formed from the hardened saliva of serpents has been discredited. Hag stones have lots of applications. They are portals to the faery realm and provide a window to another dimension. Look through one and you can see faeries and witches. Nail one to your stable door and it will protect your horses from being ‘hag-ridden’ (ridden by witches and returned in a poor state of health) at night. Milk your cow through one and the milk will not curdle. Hag stones are an antidote to poison and a cure for various ills. Thread one on a string and hang it around your child’s neck and they won’t have nightmares. Quite useful all in all – and free to any ardent beachcomber.

Tektites

Controversy still surrounds the origins of tektites but it generally seems to be accepted that they are the product of meteorite impacts on the earth’s surface, which, millions of years ago, forced a mixture of earthly material and meteoric debris back into space. This debris then re-entered the atmosphere in the form of glasseous stones ranging from a few grams to several kilos. Not dissimilar to their terrestrial counterpart obsidian, but somewhat unnatural in appearance with a variety of shapes and colours ranging from black to translucent green, our ancestors obviously realised that these strange-looking pebbles were unearthly and attributed them with magical properties. They have been found in archaeological contexts dating back tens of thousands of years, worked as tools and utilised as jewellery.

They generally occur in four main ‘strewn fields’: the North American strewn field, associated with the Chesapeake Bay impact crater; the Ivory Coast strewn field, associated with the Lake Bosumtwi crater; the Central European strewn field, associated with the Nördlinger Ries crater; and the Australasian strewn field, with no known associated crater. An anomaly is Libyan Desert Glass (LDG), similarly found over a wide area in the Libyan desert, ranging from green to yellow in colour. It’s thought that this may have been formed by an aerial explosion, but the jury still seems to be out on this one. Recently, it was discovered that the scarab in Tutankhamun’s pectoral was in fact made of Libyan Desert Glass, perhaps suggesting that the Egyptians valued its other-worldliness. Other historical associations include Chinese references dating from the 10th century where the writer Liu Sun refers to them as Lei-gong-mo or ‘Inkstone of the Thundergod’.

Small tektite examples are relatively inexpensive and can be purchased on the internet; to hold one is an experience that cannot be judged in monetary terms – but beware fakes.

Elf-shot

We have plenty of evidence of our ancient ancestors, often in the form of stone tools. However, the existence of such artefacts was unfathomable to our not-so-distant relatives and they often attributed their presence to strange events or supernatural beings. Many maladies and complaints, such as rheumatism and arthritis, were historically blamed on beings from the faery realm firing arrows known as elf-shot. (They were demons rather than fairy-tale characters.) These apparently caused all sorts of maladies in both humans and animals. The obvious proof for this was the Neolithic and Mesolithic flint arrowheads left by the ‘elves’. These were then used as protective amulets; some were mounted in silver and worn around the neck. Alternatively, an arrowhead might be placed in water, whereupon it would supposedly produce a philtre or curative drink. Mounted examples from antiquity are rare and much sought after by collectors.

Similarly, ancient stone axe heads, slingshot stones and fossils such as belemnites were thought to be thunderbolt cores. They were also used as protective amulets and have frequently been found in tombs and graves and built into the walls of medieval buildings.

Bezoar stone

Derived from the Persian pād-zahr, meaning ‘antidote’, a bezoar stone, like many of its mythical counterparts, was thought to be an antidote to poison. The ‘stones’ are formed in the stomach or intestines of most living creatures (the most sought-after come from a type of Persian goat) and are composed of indigestible matter such as hair and plant fibre. Bezoars can take on a crystalline form and although we know that they are ineffective in dealing with poison generally, there may be some truth in the fact that certain varieties are capable of absorbing arsenic.

Bezoars were much-treasured objects and historical specimens from the royal courts and Wunderkammers (wonder rooms) of Europe are often ornately mounted with precious metals and jewels or housed in wonderful cabinets. Antique specimens are eagerly sought; so too are their man-made equivalents, Goa stones, named after their place of origin. Usually made of a clay, crushed ruby, gold leaf, shell, musk and resin conglomerate, Goa stones were invariably contained within an ornate silver or gold filigree holder. They were immensely valuable and a 16th- or 17th-century example was worth far more than its weight in gold. Consequently, they are still very valuable today.

NB: The trading of modern bezoars from endangered species is common in the Far East. The internet is awash with fakes and illegally sourced stones – beware!

Toad stone and tongue stone

The Lepidotes was a fish that lived in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Its peculiar button-shaped teeth were used for crushing molluscs and they are preserved in the fossil record as shiny button-like nodules. At some juncture in history, these fossilised teeth became associated with the toad, a much-maligned and ostracised creature commonly associated with witchcraft. The stones were thought to be present in the heads of toads and extricable by a number of different methods, including sitting the toad on a red cloth.

The stones apparently warmed up when placed in the proximity of poison (surprise, surprise) and were often mounted in gold rings or in jewellery, now prized by collectors. The stones can be easily purchased on the internet but it’s the magical association that’s important to serious collectors. Shakespeare’s reference in As You Like It sums up the general feeling about toads in the 16th century:

Sweet are the uses of adversity;

Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.

Sharks’ teeth, which are among the most commonly occurring fossils on the planet, have a similar meaning in historical terms: they were thought to be the petrified tongues of dragons and snakes, or ‘tongue stones’. They were carried as amulets and also used to divine poison. It seems that the threat of being poisoned was a general preoccupation in the medieval world.

Coco de Mer

The fabulously sensual-looking Coco de Mer is a ‘fruit’ that closely resembles a pair of female buttocks. It’s the biggest seed in the plant kingdom, weighing up to a staggering 30 kilos. Until 1768, its origins were completely unknown and it was thought to grow on mythical trees at the bottom of the ocean. In fact the palms that bear them grow only on the Seychelles (which were uninhabited). The hollow shells of the germinated seeds would be carried on the tides and washed up on the shores of the Maldives, whence they were traded around the world as objects of curiosity – hence their other name, Maldive coconuts. Much like bezoars, they would be polished and mounted in precious metals, making enigmatic additions to a European cabinet of curiosity. They also found favour in the Islamic world and sometimes turn up in the form of Dervish kashkuls or begging bowls, the exteriors ornately carved and decorated with copper mounts and handles. I recently saw a completely plain and unadorned example make over £6,000 at auction – not bad for a nut.

THE ANTIQUES ROADSHOW: A NATIONAL TREASURE

The British are obsessed by antiques. I use the word ‘antiques’ loosely because applied in its broadest sense it throws its comforting arm around a whole plethora of disciplines and genres ranging from Rembrandts to beer mats. The Antiques Roadshow is regarded by its adoring public as the Linus blanket of the television world, a national treasure, much copied but never bettered. In a digital world where TV audiences for live broadcasts are ever diminishing, it still regularly attracts over 6 million viewers. It’s also among the longest running factual programmes on British television and airing its 36th series as this book goes to press.

I watched it in my teenage years, hooked from the word go, little knowing that I would one day be part of this esteemed institution. Having served on fifteen series and now working with my third presenter (Fiona Bruce, successor to Michael Aspel and Hugh Scully), I’m just beginning to feel like I have finished my apprenticeship – and it has been an honour. I’m what’s known as a ‘miscellaneous’ specialist, which means I deal with just about every facet of the antiques and collectables world that you can imagine. This stems from my background as a general auctioneer – our queue is normally the longest!

So what is it about the Roadshow that has so captured the imagination of millions of viewers on cold winter Sunday evenings? The cynical among you might say that it’s about greed and avarice. Those are strong words and although it’s impossible to deny the lure of high-value discoveries, it has far more to do with passion and personal stories: both the passion of the specialist and the interests of the owner. The programmes reflect a mixture of values, which we as the go-betweens hope to put across to the viewers in a way that reflects our love for the subject, our empathy for the often poignant objects that we deal with and the high production values of the BBC.

If you’ve ever wondered how many people we’ve seen and how many objects we’ve handled, here are a few statistics to digest. As it currently stands, there have been 700 programmes made at 530 venues; eleven of those venues were in foreign countries, including Australia and Canada, where the Roadshow is immensely popular – in 2005 the visit to Australia prompted 25,000 ticket applications for just two shows! The format is also licensed in many countries, including places as diverse as America and Sweden, where they have their own versions.

Each show is visited by around 2,000–3,000 guests. It’s estimated that specialists on the show have seen and valued around 9 million objects in total, of which approximately 20,000 have been filmed. No one is ever turned away on the day and it’s a matter of pride that every person gets seen, no matter whether it’s a humble cup and saucer or a valuable Fabergé brooch.

Protecting the spontaneity of the recordings is always of paramount importance. In these days of the internet, owners often can’t resist finding out all they can before they arrive (we hate that) so it’s doubly exciting when you find a genuinely surprising object that you can enthuse over.

I’m often asked things like ‘Is it a fix? Someone told me you know what’s coming in advance; how come you always have those big bits of furniture on the show?’ We quite simply put an ad in the local paper close to where we are scheduled to film and wait for people to write in. After the office has received a hundred or so letters, we set off the week before with an advance party of two and visit as many people as we can. Having made some informed decisions, without giving any details away and often having to exercise great restraint, Pickfords pick up a few bulky pieces belonging to those who can’t physically move the items themselves and we make a few appointments to get the cameras rolling in the morning before the queues filter through (since idle cameras cost money!).

A normal day involves filming around 50 objects and it’s typical for a specialist such as myself to film between two and four pieces, although that very much depends on what turns up on the day.

So what, after all these years, are the objects that most stick in my mind? Napoleon’s attaché case was pretty exciting; Marc Bolan’s Gibson Flying V guitar was also impressive; a plate from Captain Scott’s ship the Terra Nova, probably handled by the great man, was a very powerful object; and a torch made from an old OXO tin in the Second World War, presented by a glamorous lady in 1940s dress … all part of a typical day’s work on the Antiques Roadshow.

Before motorised lawnmowers with large pneumatic tyres floated gracefully over our lawns, horses or ponies generally did the job of pulling large mowing machines. In order to stop their hooves churning up the grass and ruining the surface, the Victorians had a novel idea – lawn boots. They come in two distinct varieties, leather boots (‘bag type’) or screw-on plate types. H. Pattison & Co. of Streatham, London, made over 30 different sizes in the late 19th century. Unlike most shoes, these naturally come in sets of four, and are, not surprisingly, a niche collectable.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Collecting is like eating peanuts, you just can’t stop

—Anon

We all know that stamp collectors are called philatelists; in fact, if you were to try and summon up half a dozen names for collectors you’d probably just about manage it. One of my favourites is the name given to cigar band collectors – brandophilists. The current record holder is an American called Joe Hruby who is listed in the Guinness book of records as possessing 165,480 – although apparently that figure has long since been exceeded and now stands at over 220,000. His collection was accumulated over 70 years.

I’ve scouted around for a general title to cover my own multifarious collecting habits but can’t really find a good term for a general collector. There are a few different names for hoarders, ‘syllogomania’ being one of them, but this usually refers to more extreme OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder)-related cases. Perhaps a ‘generalist’ will suffice; however, if you collect a little bit ‘off piste’ then it’s still possible to officially categorise yourself. Here are a few terms that might cover your particular collecting passion. This is by no means exhaustive but it might help you when you do your next crossword puzzle.

Ambulist – Walking sticks

Arctophilist – Teddy bears

Argyrotheocologist – Moneyboxes

Bibliophile – Books

Brolliologist – Umbrellas

Cagophilist – Keys

Cartomaniac – Maps

Conchologist – Shells

Cumyxaphilist or Philluminist – Matchboxes, matchbooks and labels

Deltiologist – Postcards

Digitabulist – Thimbles

Discophilist – Gramophone records

Exlibrist – Book plates

Fromologist – Cheese labels

Fusilatelist – Phone cards

Helixophilist – Corkscrews

Labeorphilist – Beer bottles

Lepidopterist – Butterflies and moths

Notaphilist – Banknotes

Numismatist – Coins

Palaeontologist – Fossils

Philographist – Autographs

Plangonologist – Dolls

Rhykenologist – Woodworking planes

Scripophilist – Bonds and share certificates

Sphragistiphist – Seals and signet rings

Tegestologist – Beer mats

Vecturist – Transport tokens

Vexillologist – Flags

The suffixes ‘ana’ and ‘ilia’ are often used in the world of collecting to denote an assemblage of items related to a field. Such words can often seem trite: commonly used are ‘tobacciana’, ‘railwayana’, ‘Americana’, ‘Victoriana’ and ‘automobilia’.

NAPOLEON’S PENIS

What you are now we used to be, what we are now you will be.

—Inscription in the crypt of the Capuchin monks in the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, Rome

The collecting of human body parts is an area in which I have a particular interest; it’s an issue that raises all sorts of moral questions, mainly because different cultures and religions view the treatment of mortal remains in vastly different ways. Strangely, our inherent curiosity for the macabre tends to often override our judgement in these matters. Religion and religious custom, in particular, play an enormous role in our perception of what is acceptable.

My personal collection extends to a skull that we affectionately nicknamed Doris, a few reliquaries containing various parts of ‘saints’, some finger bones from a crypt and a cannibal’s knife from the Sepik River region of New Guinea – it’s fashioned from a human leg bone.

Hmmm, I hear you say, why would anyone want to own that? Firstly, it’s important to look at the way these objects tie in historically and culturally. My first such acquisition was made in my early 20s and it helped to mould my thinking on the subject. I purchased a Tibetan skull adorned with silver appliqués and semi-precious stones. The cranium was hinged and lined with silver. I remember that first evening looking at it on the mantelpiece and thinking about the person it had once been. I’d made some enquiries on Tibetan views of death and had already come to the conclusion that the Buddhist notion ‘that once the consciousness has left the body it doesn’t matter how the body is handled or disposed of because in effect, it has just become an empty shell’ was very sensible. I felt I had the justification for owning the skull and have since tended to apply Buddhist principles to my collecting habits.

However, it’s a subject that has simmered away for ages, causing our museums to repatriate shrunken heads and other religious or culturally important body parts on a far less public scale than the controversy surrounding the Elgin marbles. (See Did Elgin Steal the Marbles? page55.)

So where does Napoleon’s penis fit into this? Well, this is a salutary lesson on not making too many enemies and not being too infamous. It seems the more notorious you are, the more likely that people will want a piece of you – after you are dead. Taking a lock of hair is acceptable and a time-honoured measure of love and remembrance, but Napoleon had unfortunately left his physician, Dr Francesco Antommarchi, out of his will. On his death in 1821, an autopsy was carried out in the presence of seventeen worthies and officials. Gossip soon circulated about the ‘souvenirs’ that had been taken from Napoleon and his deathbed, including blood-stained sheets, hair, parts of his intestine and so on. Somehow, it seems, Napoleon’s chaplain, the Abbé Ange Vignali, acquired his penis and it stayed with the family until 1916 when it was sold at auction to an unknown British collector.

In 1924 it was purchased by an American collector, A.S.W. Rosenbach, for £400. He used it as a conversation piece and even loaned it to the Museum of French Art in New York. It was again auctioned in 1969 but failed to sell and was acquired some eight years later at an auction in Paris by the eminent American urologist Dr John K. Lattimer for the equivalent of around $3,000. He died in 2007, leaving it to his daughter, who still owns it. Rumour has it that she has turned down an offer of $100,000 for the appendage.

For those curious as to its appearance, unfortunately no one is permitted to see it, but type ‘Napoleon’s penis’ into YouTube and you can watch a four-minute film of the writer Tony Perrottet enjoying a private viewing. On behalf of Napoleon I feel obliged to point out that anything mummified shrinks, and so it can safely be assumed that it was at one time considerably larger than it is now.