5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

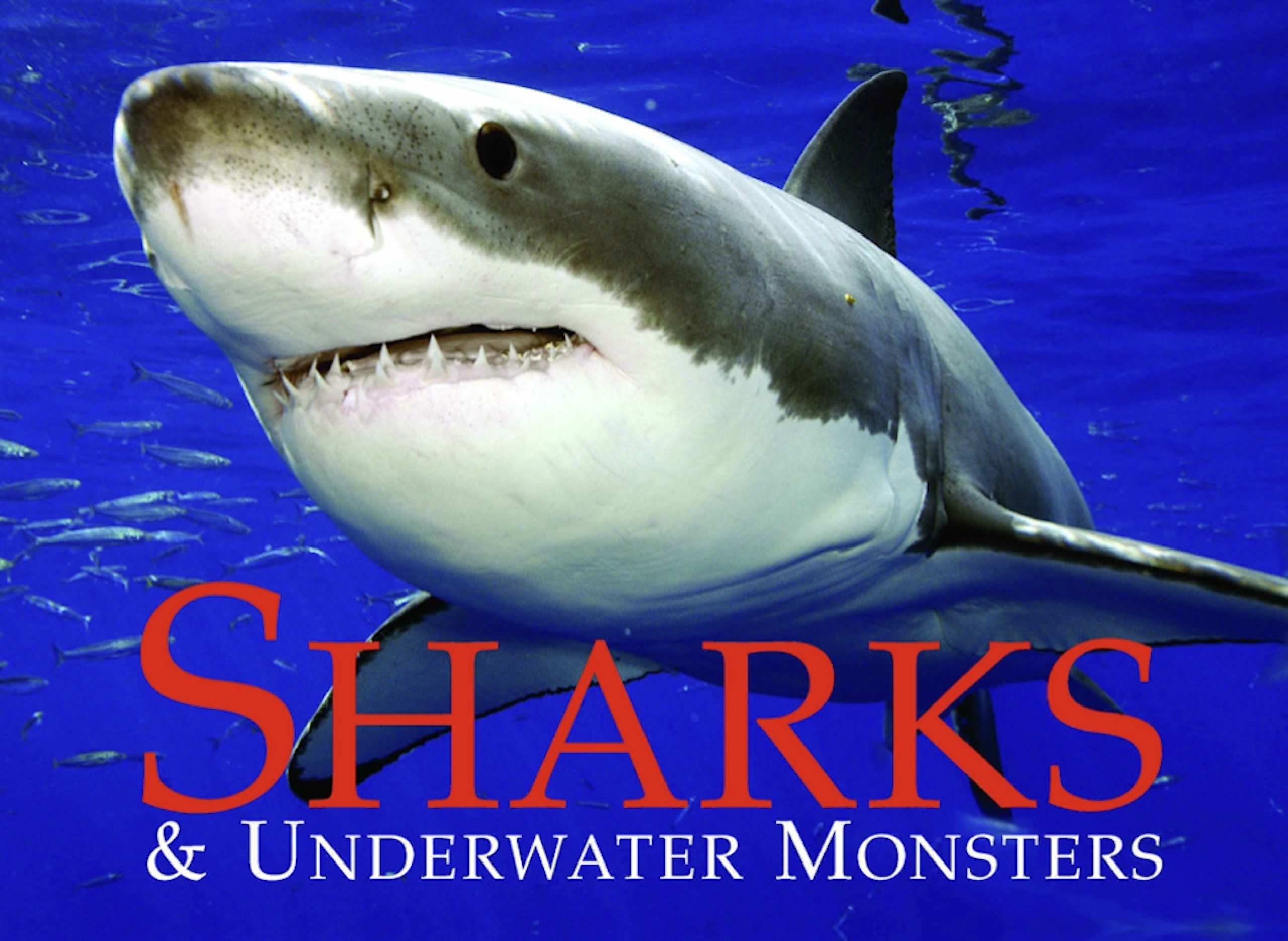

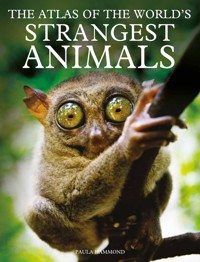

Illustrated throughout with outstanding full-colour artwork and detailed photographs, Atlas of the World’s Strangest Animals presents an in-depth look at 44 of the most unusual species. The selection spans a broad spectrum of wildlife, from the tallest land living mammal, the Giraffe, to the light, laughing chorus of Australian kookaburra birds to the intelligence of the Bottlenose dolphin to the slow pace of the three-toed sloth. With chapters devoted to each of the continents and the world’s oceans, a spread is devoted to each animal with a map indicating its geographical distribution. Fact boxes offer fascinating details on the animal’s lifecycle and habitat. Ranging from the world’s oceans to the tropics and including egg-laying mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, cannibalistic insects and other invertebrates, Atlas of the World’s Strangest Animals is a fascinating introduction to some of nature’s most curious beasts.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 255

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

THE ATLAS OF THE WORLD’S

STRANGEST

ANIMALS

PAULA HAMMOND

This digital edition first published in 2019

Published byAmber Books LtdUnited HouseNorth RoadLondon N7 9DPUnited Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.ukInstagram: amberbooksltdFacebook: amberbooksTwitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2019 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-232-6

Picture CreditsArtwork credits: All © International Masters Publishing LtdPhoto credits: Dreamstime: 23 (Heinz Effner), 37 (Siloto), 44 (Anthony Hall), 75 (Ongchangwei),117 (Artur Tomasz Komorowski), 191 (Steffen Foerster), 199 (Maya Paulin), 202 (John Abramo);FLPA: 10 (ZSSD/Minden Pictures), 30 (Ron Austing), 41 (Stephen Belcher/Minden Pictures),67 (Foto Natura Stock), 91 (Scott Linstead/Minden Pictures), 108 (Scott Linstead/Minden Pictures),138 (Heidi & Hans-Juergen Koch/Minden Pictures), 154 (Thomas Marent/Minden Pictures),172 (Matt Cole), 185 (Gerard Lacz), 206(Flip Nicklin/Minden Pictures), 211 (Norbert Wu/Minden Pictures); Fotolia: 60 (Herbert Kratky),70 (Seraphic 06); iStockphoto: 57 (Susan Stewart), 135 (Marshall Bruce), 218 (Alex Koen); Photos.com: 15, 27, 83, 96, 194; Stock.Xchang: 86 (David Hewitt), 214 (Obe Nix); Webshots: 112 (Addan104); Wikipedia Creative Commons Licence: 78 (Dacelo Novaguineae),126 (Mila Zinkova), 143 (Malene Thyssen)

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review nopart of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher.The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge.All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher,who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Contents

INTRODUCTION

AFRICA

AARDVARK

NAMIB WEB-FOOTED GECKO

GIRAFFE

HOOPOE

JACKSON’S CHAMELEON

NAKED MOLE RAT

ASIA

GHARIAL

JAPANESE MACAQUE

MUDSKIPPER

PROBOSCIS MONKEY

RATEL

SIAMESE FIGHTING FISH

TARSIER

AUSTRALASIA

DUCK-BILLED PLATYPUS

EMU

KOALA

LAUGHING KOOKABURRA

RED KANGAROO

SHORT-BEAKED ECHIDNA

SUGAR GLIDER

NORTH AMERICA

AMERICAN BULLFROG

AMERICAN COCKROACH

AMERICAN MINK

BIG BROWN BAT

GREAT GREY SHRIKE

MANTIS

SOUTHERN FLYING SQUIRREL

CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA

EMPEROR TAMARIN

GIANT OTTER

HOATZIN

SURINAM TOAD

PYGMY MARMOSET

RED HOWLER MONKEY

SOUTHERN TAMANDUA

THREE-TOED SLOTH

EUROPE

COMPASS JELLYFISH

CUCKOO

DEATH’S HEAD HAWKMOTH

EUROPEAN HONEYBEE

GREAT DIVING BEETLE

SKYLARK

WELS CATFISH

THE OCEANS

ANGLERFISH

BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN

CLEANER WRASSE

COMMON OCTOPUS

NARWAL

OPALESCENT SQUID

SEA ANEMONE

SEAHORSE

INDEX

Introduction

Great diving beetle

According to a study in 2007, 1,263,186 animal species have so far been been named and scientifically described. This includes 950,000 species of insects, 9956 birds, 8240 reptiles, 6199 amphibians and 5416 mammals. When we consider that there are still parts of the world that are so inhospitable no human has ever set foot there, then it’s possible we may never know for sure just how many species we really share our planet with. However, what is certain is that many of the animals we are familiar with are truly remarkable. If we were to flick through this list of 1,263,186 species then, within it, we would find some of nature’s greatest curiosities: mammals that can fly and birds that can’t; frogs as small as fingernails and birds as big as horses. Here, we’d discover walking fish, brainless jellies, cannibals and camouflage experts.

Tarsier

Common octopus

Three-toed sloth

Sugar glider

Life, it seems, comes in all shapes and sizes – many of them very strange indeed. Who, for instance, could have invented a fish with its own, in-built fishing rod; a poisonous mammal that lays eggs; or brightly coloured reef-dwellers that run their own, highly successful cleaning ‘service’? In this book you’ll find 50 of these seriously strange creatures including some, perhaps, that we’re so well acquainted with, at first glance, they may seem quite mundane. If only we were able to fully explore the deepest oceans, driest deserts and highest mountain tops, then who knows what other marvels we might add to this list of wonders?

Mantis

Naked mole rat

Africa

From dew-drenched forests to parched deserts, from glorious grasslands to sun-baked beaches, Africa is a continent that both stimulates and surprises.

∼

This vast landmass, spread across 300,330,000 square kilometres (11,600 square miles), is the world’s second-largest continent, encompassing more than 50 nations and a billion people. In the north of this tearshaped land is the great Sahara Desert, which sprawls, untamed, across an area larger than the United States of America. On the edge of this sea of sand, the desert starts to disappear, giving birth to swathes of scrubby grassland known as savannah. These are regions that depend on one season of the year for most of their rainfall, and many animals roam across these regions in pursuit of the rains. In fact, the Serengeti savannah plays host each year to the largest, longest overland migration in the world.

In central Africa, nestled in the Congo Basin, is the continent’s great rainforest. This beautiful region is the second-largest rainforest on Earth. It’s an area of dense, steamy jungle, which contains around 70 per cent of all of Africa’s plant life and an estimated 10,000 animal species – many found nowhere else.

Thanks to such a rich variety of ‘ecosystems’, the African continent supports a bewildering array of weird and wonderful wildlife. It’s here that you’ll find many of the world’s biggest, fastest and most dangerous species. It’s also home to some of our planet’s animal ‘superstars’ – the elephants, lions and zebras that appear so often on our television screens. But there’s more to this amazing land than killer cats and wild game. In this section, you’ll read about some of Africa’s more curious inhabitants – rodents that behave like insects, ‘living fossils’ and some genuinely strange record-breakers!

Aardvark

Aardvarks are surely Africa’s most curious-looking mammals. With their almost hairless bodies, rabbit-like ears, a toothless snout and snakelike tongue, these ‘earth pigs’ are so odd that scientists still struggle to classify them. With no known relatives they have been described as ‘living fossils’.

Key Facts

ORDER Tubulidentata / FAMILY Orycteropodidae /GENUS & SPECIES Orycteropus afer

Weight

49.9–81.6kg (110–180lb)

Length

Up to 1.8m (6ft) including tail

Sexual maturity

2 years

Breeding season

May–June near equator; October–November southern Africa

Number of young

Number of young: 1

Gestation period

7 months

Breeding interval

Yearly

Typical diet

Typical diet:Termites and other insects

Lifespan

Up to 23 years in captivity

TeethAardvarks have no front teeth. Instead, they rely on strong ‘cheek teeth’ at the back of the mouth to grind up food.

ClawsPartially webbed second and third toes and a set of strong, sharp, hooflike claws make aardvarks superb tunnellers and diggers.

EarsBeing night-time specialists means that aardvarks must rely, primarily, on their senses of smell and hearing to track down termites.

‘Aardvark’ is famously one of the first words you’ll find in an English language dictionary. The name comes from Dutch Afrikaans and means ‘earth pig’, which is exactly what European settlers thought these strange mammals looked like. However, although these shy and solitary creatures do have piglike bodies, they’re no relation. In fact, genetically speaking, aardvarks are a puzzle.

When classifying living things, scientists begin by looking for similarities between known species. But can you think of any other burrowing, nocturnal mammal that has a powerful tail, rabbit-like ears, webbed toes, claws resembling hooves and a long sticky tongue? It’s a problem that has stumped scientists for decades.

Initially, the solution was to choose a ‘best fit’ by placing the aardvark in the same order as armadillos and sloths (Edentata). Later, a new order was created especially for the aardvark – Tubulidentata. Edentata means ‘toothless ones’ and armadillos and sloths both lack front, incisor teeth. Adult aardvarks have no front teeth either, but they do possess extremely odd ‘cheek teeth’ at the back of their jaws. In place of the usual ‘pulp’ in the centre of each tooth are fine tubes bound together by a hard substance called cementum. Hence the name ‘Tubulidentata’, meaning tube-toothed.

To date, the aardvark is the only known member of the order ‘Tubulidentata’ and the situation is likely to remain that way. Although a few fossilized remains have been found, they provide no clues to the aardvarks’ ancestry or their relationship to other species. These curious beasts seem to be living fossils. They may have been very successful as a species, but they’re an evolutionary dead end. They have distant relatives today, including elephants, and their common ancestor probably dates back to the moment when the African continent split from the other landmasses.

Terrific tunnellers

From grassy plains to woodland scrub, aardvarks enjoy a variety of habitats, but you’re unlikely ever to see one ‘in the flesh’. That’s because they spend much of the day in their burrows, emerging only late in the afternoon or even after sunset. Then they may range up to 30km (18.6 miles) in the search for food – ants, termites and the aardvark cucumber, the only fruit they will eat.

Comparisons

With their thickset bodies, stocky limbs and long snout, the giant pangolin (Manis gigantea) of west Africa resembles an heavily armoured aardvark. Although the two mammals are not related, they have similar body shapes, due to similar lifestyles – both eat termites. Despite their name, giant pangolins are actually smaller than aardvarks. The largest males grow up to 1.4m (4.6ft), although their overlapping scales make them look bulkier.

Giant Pangolin

Aardvark

Above ground, aardvarks appear slow and clumsy, but when danger threatens, these cautious creatures can move with surprising speed – bolting for the safety of the nearest subterranean sanctuary. Most aardvarks have several burrows in their territory. Some are just temporary refuges, comprised of a short passageway. Others are extensive tunnel systems connecting several entrances, with a spacious sleeping chamber at one end. Even if an animal is caught away from its burrow, this presents few problems. Aardvarks are terrific tunnellers and, if trouble strikes, they can dig themselves to safety in a matter of minutes.

When digging, the aardvark rests on its hind legs and tail, pushing the soil under its body with its fore feet and dispersing it with its hind feet. This is such an efficient technique that there are records of one aardvark digging faster than a team of men with shovels! Such a powerful set of claws and paws also make superb defensive weapons. When cornered, these stocky animals can give as good as they get. Tail and claws combined are usually enough to deter all but the hungriest predator. If that doesn’t do the trick, the aardvark will often roll onto its back so that it can strike out with all four feet – a killer combination.

Aardvarks are ‘nocturnal’ and are most active at night. On warm evenings, they emerge from their burrows just after dusk.

Keeping his sensitive nose to the ground, this hungry aardvark patrols the area with a zigzagging motion, until he sniffs out a termite mound.

Powerful claws create a hole in the side of the mound, through which the insects swarm to attack the unwelcome invader.

Up to 45.7cm (18in) long, the aardvark’s sticky tongue is its secret weapon – perfect for lapping up termites or ants! The aardvark’s thick skin protects it from the insects’ stings.

Namib Web-footed Gecko

Despite the extreme heat of Africa’s Namib Desert, there’s one little lizard that thrives in these energy-draining conditions. But they’re not like any lizard you’ve ever seen. In fact, the translucent skin of these odd geckos make them very difficult to spot at all!

EyesBig eyes are designed to gather as much light as possible – invaluable for a species that hunts in the dark.

MouthGeckos have no need for large, tearing teeth. Instead, they make do with small, compact teeth to crush insects.

Key Facts

ORDER Squamata / FAMILY Gekkonidae /GENUS & SPECIES Palmatogecko rangei

Weight

Not recorded

Length

12–14cm (4.7–5.5in)

Sexual maturity

Not recorded

Breeding season

Throughout the year

Number of eggs

2

Incubation period

56 days

Breeding interval

Several times a year possible

Typical diet

Beetles and spiders

Lifespan

Up to 5 years in the wild

FeetFleshy webs act like ‘snow shoes’, enabling geckos to walk on the surface of the sand without sinking.

We are all shaped by our environment. However, in the sand dunes of south-west Africa there is a species of gecko that has evolved some very unusual characteristics to cope with desert living.

Geckos are found in warm, tropical regions. In Africa alone, there are approximately 41 species. Around eight are found in the area of the Namib–Naukluft National Park, part of the Namib Desert, which is thought to be the world’s oldest desert. Many of these are arboreal species and have famously bristly feet, which enable them to ‘stick’ to almost any surface. As their name suggests, though, Namib web-footed geckos have their own special adaptation to survive in the desert sands.

Unlike their tree-dwelling cousins, web-footed geckos don’t need to be able to cling to vertical surfaces (although they are still good climbers). Instead, their feet are designed to spread their weight so that they don’t sink into the sand. Their webbed feet also have an handy, extra ‘feature’. They contain small cartilages – stiff connecting tissues – that support a complex system of muscles. These allow the geckos’ feet to make highly coordinated movements. So, to escape the baking heat of the midday sun, they simply chill out in burrows that they’ve specially dug for the purpose. Their foot design makes them superb tunnellers, and these burrows can be up to 50cm (19.7in) long.

Our web-footed friends also have several other physical adaptations that make them real desert specialists. Most geckos, especially the stunningly vibrant day geckos (genus Phelsuma), are extremely colourful and, ironically, this helps them to blend in with the rich colours of the rainforest. In contrast, web-footed geckos have thin, almost translucent, pink skin, which makes them virtually invisible when viewed against the dusky desert sands.

Caught in the open, this web-footed gecko adopts a defensive posture, emitting loud clicks and croaks to intimidate the approaching predator.

Undeterred, the hungry hyena makes a grab for the little lizard, only to be left with a tail-end titbit: the gecko has dropped its tail in self-defence.

All geckos have the capacity to detach their tails and, for this gecko, it turns out to be a life-saving ability.

While the hyena munches down the detached tail, the gecko survives to live another day – and grow another tail!

Comparisons

Apart from skinks (family Scincidae), geckos are one of the most diverse groups in the reptile kingdom. There may be as many as 900 separate species and they come in all sizes. The two smallest are dwarf geckos – Sphaerodactylus ariasae and Sphaerodactylus parthenopion – which are both less than 1 cm (0.4in) long. That’s 14 times smaller than the biggest web-footed gecko!

Sphaerodactylus parthenopion

Web-footed gecko

Six-lined racerunner

Strange sights

According to John Heywood’s book of proverbs (1546) ‘All cats are grey in the dark.’ It’s a saying that holds true for humans. We see poorly in the dark – generally just fuzzy tones of black and white. So it’s easy to imagine that geckos would have a hard time finding their way around at night. Not so. New research has revealed that they may see better in the dark than we do.

All geckos have extremely large eyes to gather as much light as possible. Those species that are active during the day tend to have rounded pupils, but nocturnal reptiles, like the web-footed gecko, have vertical pupils. By day, these pupils narrow to tiny slits to protect the sensitive retina at the back of the eye from damage. According to researchers from Lund University, Sweden, this ‘design’ has other advantages too. It seems that slit pupils allow those animals with colour vision to see sharply focused images at night – something that no human can do.

Light travels at different wave lengths depending on its colour. Human eyes have single-focus lenses, which means that not every colour is in focus when it hits the lens. Many animals solve this problem with multi-focus lenses, where different parts of the lens are ‘tuned in’ to different wave lengths. With round pupils, parts of the lens is covered every time the pupil expands or contracts. With a slit pupil, the whole diameter of the lens remains uncovered, allowing every colour to stay in focus. What’s more, according to specialist work on nocturnal vision, colour vision is much more common in the animal kingdom than was once assumed, and geckos probably have excellent colour, as well as night, vision.

Giraffe

Standing tall amongst the grasses of Africa’s great, sun-parched savannahs, giraffes are an impressive, and extraordinary, sight. With their bold, leopardprint coats, camel-like head, horns, stubby tail, long legs and phenomenal necks, these astounding animals really do have to be seen to be believed.

Tongue and LipsA blue tongue, which is 53cm (20.8in) long, and flexible lips, are used to pluck leaves off the thorn trees.

Legs and HoovesLong, powerful legs are used to lash out at predators. Hooves are cloven (split) and leave a distinctive square-toed print.

NeckMost mammals have seven cervical vertebrae (neck bones), regardless of their size. Those in the giraffes’ neck are extremely large.

Key Facts

ORDER Artiodactyla / FAMILY Giraffidae / GENUS & SPECIES Giraffa camelopardalis

Weight

Males: 800–1930kg (1763.8–4254.9lb)Females: 550–1180kg (1212.5–2601.4lb)

Length

Males: Up to 5.5m (18ft) Females: up to 4.5m (14.8ft)

Sexual maturity

4–5 years

Breeding season

All year

Number of young

1; occasionally twins

Gestation period

15 months

Breeding interval

Females become receptive every 2 weeks

Typical diet

Leaves and buds

Lifespan

Up to 25 years in the wild; 28 in captivity

Take one look at a giraffe, and it’s easy to see why the Romans named them ‘camel leopards’. Their heads and long legs do have a camel-like shape, while their spotted coat is reminiscent of that worn by the leopard (Panthera pardus). However, Arab peoples had an even more appropriate name – ziraafa, meaning ‘assemblage of animals’, which is exactly what they look like! The short, brush-ended tail, for instance, could well belong to a warthog (Phacochoerus africanus). The long tongue seems to be more appropriate for a reptile, like a chameleon, than a mammal. Indeed, it’s so long that they use their tongues to wipe off any bugs that land on their face. Add to this mix a set of cloven hooves (like pigs), a pair of stubby horns and that enormously long neck, and these animals really do look like they are made from bits and pieces taken from other beasts.

For a giraffe, being born can be a traumatic experience. Babies emerge head first and fall to earth with a thud!

As the birth sac breaks open, the young giraffe tumbles, headfirst, up to 2m (6.6ft) to the ground!

Undaunted, the newborn looks around, while his mother gets busy cleaning him up with her long, mobile tongue.

Despite his dramatic entrance into the world, he is quickly on his feet and ready to take his first shaky steps.

Such an eclectic mix of body parts has, however, made the giraffe one of the African savannah’s great success stories. A long neck means that they can feed on foliage not accessible to other animals. Their prehensile (gripping) tongue and mobile lips enable them to pull hard to reach buds and leaves into the mouth with ease. Their coat provides them with superb cryptic camouflage, so they can blend in with the dry grasses of the African plains. Their hooves are powerful enough to crush the skull of a lion or break its spine, although giraffes are rarely bothered by predators. Instead, their long legs simply carry them out of trouble at speeds of up to 56km/h (35mph).

Their closest relatives – the okapi (Okapia johnstoni) – are equally odd. Their front half resembles a short, brown giraffe. The back looks like a zebra!

Tall tales

Thanks to their long legs and elongated necks, giraffes are the world’s tallest mammals. The tallest-ever giraffe measured in at 6m (19.7ft), but an average is between 4.4m and 5.4m (14.8-18ft). Almost half of this is made up of the animal’s extraordinary neck, which can be up 2.4m (8ft) in length and weigh up to 272kg (599.6lb). Legs account for another 2m (6.6ft) of this record-breaking bulk; the front legs are slightly longer than the hind legs.

What is so remarkable about these great beasts is that these enormous necks contain only seven vertebrae. That’s the same as in humans. Of course, each vertebrae can measure up to 25.4cm (10in) long! Even more incredible is that each vertebrae is bound together with ball-and-socket joints. In humans, such joints link our arms to our shoulders. These giants make giraffes’ necks not just long but very flexible.

The reason for the development of such an extraordinary physique has been the subject of much scientific debate. Some argue that it’s an adaptation for feeding on the tall arcacia trees that form such an important part of the giraffes’ diet. Others believe that long necks form part of the giraffes’ sexual display, because males use them like clubs in the mating season to slug it out with rivals. Whatever the reason, in each case, giraffes with the longest necks would have more food and more mates and so be more likely to survive to produce longnecked offspring.

However, long necks haven’t been all good news for the giraffe. They need a massive heart and a highly specialized cardiovascular system just to pump blood from their body up to their head!

Comparisons

No one knows for sure how many subspecies of giraffe there are, but each animal has its own, distinct markings, like fingerprints. Reticulated giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata) have large, polygonal liver-coloured spots, defined by bright, white lines. Rothschild’s giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi) tend to have deep brown blotches or rectangular spots. And Maasai giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi) have jagged-edged spots of chocolate-brown on a cream-yellow background.

Maasai giraffe

Hoopoe

With their dramatic head crest and striking plumage, it’s no wonder that hoopoes have inspired so many myths and legends. Yet these beautiful birds have one unenviable and strange claim to fame. While other birds preen and clean, hoopoes revel in muck and mess!

CrestThe hoopoes’ dramatic crest is flat at rest, but it can be raised when the bird is alarmed or excited.

FeetHoopoes have anisodactyl feet, with three toes facing forwards and one facing backwards. This is common for perching birds.

JuvenileYoung hoopoes take some time to develop the characteristic elongated, curved bill, long tail and impressive crest worn by adults.

Key Facts

ORDER Coraciiformes / FAMILY Upupidae/ GENUS & SPECIES Upupa epops

Weight

46–89g (1.6–3. loz)

Length

25–29cm (9.8–1 1.4in)

Wingspan

44–48cm (17.3–18.9in)

Sexual maturity

Few months after fledging

Breeding season

April–Sept, but varies across range

Number of eggs

7–8 eggs; up to 12 in warmer regions

Incubation period

15–16 days

Breeding interval

Yearly

Typical diet

Large insects and small reptiles

Lifespan

Up to 10 years in the wild

Comparisons

Worldwide, there are approximately nine subspecies of hoopoe. These beautiful birds can be found from northern Europe to east Asia, but it’s in Africa that they’re most at home. Hoopoes are happiest with bare earth beneath their feet and cavities to nest in, which allows them to enjoy a wide range of habitats. Their cousins, the wood-hoopoes, are much choosier preferring open woodland and savannah.

Wood-hoopoe

Hoopoe

Dirt brings disease, which is why no sensible bird would ever foul its own nest, but hoopoes seem to positively adore dung!

These odd birds build their nests in cavities, usually in trees or rock faces, although any suitably sized hole will do. Hoopoes have even been found nesting in pipes, discarded burrows and termite mounds. Yet, despite their elegant and refined appearance, they are terrible housekeepers. In fact, it’s easy to hunt out a hoopoe nest because they smell so bad!

Breeding females and their chicks produce a foul liquid from their preen gland, which is said to smell like rotting flesh. Added to that, the birds excrete waste directly into the nest, and the blue eggs are very dirty by the time the chicks hatch. The chicks also foul the nest, so by the time they are ready to fly, their homes, and often the birds themselves, are alive with ticks, flies and maggots. No wonder that some people call these birds hoop-poos!

However, this strangely slovenly behaviour may have a serious purpose. Animals live in a rich, sensory world where smells are commonly used to communicate, to mark territory or find a mate. Many animals also use strong smells to deter predators. Skunks, Tasmanian devils, wolverines and stink badgers are some of the most famous mammalian ‘stinkers’, but a number of birds follow the hoopoes’ example. Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis), for instance, famously projectile vomit a foul-smelling, fishy oil over intruders! But surely hoopoes are only inviting disease by failing to clean away their own excrement? No one knows for sure, but it’s been suggested that there’s method to their apparent madness. By attracting insects, they ensure that their young have a ready supply of food, exactly where they need it most – in the nest.

Myths and magic

Despite their unsavoury habits, hoopoes have inspired story-tellers and myth makers for thousands of years.

In Ancient Egypt these unmistakable birds were reputedly kept as pets, and they crop up with charming regularly in tomb paintings. On the walls of the flat-topped mastaba of Mereruka at Saqqara, for instance, a hoopoe’s nest is shown balanced on a papyrus petal. In the fantastic garden scene, painted on the tomb of Khnumhotep III at Beni Hasan, there’s an even lovelier image of a hoopoe, shown in vivid, living colours perched on an acacia tree.

In Greek myth, the hoopoe features in many stories, including the tragic tale of Tereus, Procne and Philomele. In this grim legend, Tereus rapes his wife’s sister, Philomele, and then cuts out her tongue to ensure her silence. Philomele manages to smuggle a message to her sister, and together the women plot a hideous revenge. Killing Tereus’ own son, they feed the boy’s flesh to him during a night of drunken revelry. Enraged, Tereus attacks the women, but the gods intervene, changing all three into birds. Procne becomes a nightingale, forever singing a song of mourning for her dead son. Philomele becomes a swallow. And Tereus spends eternity being mocked as the showy but slightly comical hoopoe, the bird’s crest reminding all who see it of his royal status.

In contrast, Farid ud-Din (1146-1221) immortalized the hoopoe as the wisest of all birds in his classic sequence of Iranian poems, The Conference of the Birds. Perhaps the most telling reference to this stinky creature, though, comes from the Old Testament. Leviticus 11.13-19 and Deuteronomy 14:11 list all the animals that are considered unclean to eat, including the hoopoe. Which, when you consider its dirty habits, makes very good sense indeed!

These colourful birds often stun their prey by beating it against the ground or a favourite stone. Occasionally, larger animals are subdued by repeated pecking.

Hoopoes prefer to hunt on the ground, where food is more plentiful. Insect larvae are their main prey, but even lizards are easily dealt with.

The hoopoe’s downwards-curved bill is an especially useful ‘tool’. It can grow up to 5cm (2in) long – ideal for probing the earth for food.

Jackson’s Chameleon

Chameleons have earned their place in the annals of the strange thanks to their well-known ability to change their colour to suit their mood. However, Jackson’s chameleons have other abilities that are equally strange, which could well qualify these striking reptiles as kings of the bizarre.

HornsMale chameleons have triple horns. Depending on the subspecies, females may have one or three smaller horns, or none at all.

MouthOnce prey has been caught, a set of strong jaws and rows of sharp teeth crush it before it is swallowed.

TailA prehensile, gripping tail acts just like a spare pair of hands, helping the chameleon to grip tightly on to branches.

Key Facts

ORDER Squamata / FAMILY Chamaeleontidae /GENUS & SPECIES Chamaeleo jacksonii

Weight

Not recorded

Length

20–32cm (7.9–12.6in) including tail

Sexual maturity

5 months

Breeding season

Possibly all year

Number of young

8–30

Gestation period

5–6 months

Breeding interval

Possibly yearly

Typical diet

Small insects

Lifespan

Up to 6 years in the wild; 10 in captivity

Chameleons are perhaps the most well-known of all lizards, although much of their fame is based on a misconception. Their celebrated ability to alter their skin colour happens only in response to variations in the environment or changes in the reptiles’ mood, not as a direct attempt to blend in with their surroundings. Nevertheless, how chameleons change their colour is a fascinating process and it all starts, sensibly enough, in the skin.

Chameleons have four layers of skin. First comes the nether layer, which can reflect the colour white. On top of that is the melanophore layer, which contains the dark pigment melanin, meaning that brown and black can be produced. This layer also reflects blue. Next comes the chromatophore layer, which contains yellow and red pigments. Finally there’s the outer, protective layer of the skin, called the epidermis.