2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: via tolino media

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

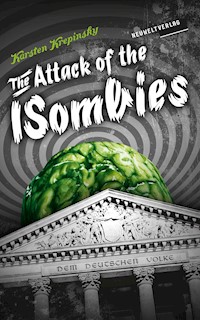

"Trashy." "Subversive." "Outrageous." Zombies have launched an attack on Berlin, slaughtering anyone who gets in their way. While politicians run for cover, a mismatched group of young outcasts stands up to the challenge… Absolutely non-PC. A subversive Zombie satire. Warning! Reading this Zombie Apocalypse might trigger PC anxiety in sensitive people, making comprehensive brain restructuring surgery unavoidable.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

KARSTEN KREPINSKY

The Attack Of The ISombies

Episode 1: They’ve Come To Turn You

Translated from the German by

KARIN DUFNER

Imprint/Impressum

Copyright (c) 2015 by Karsten Krepinsky

English translation in 2021 by Karin Dufner

www.karindufner.de

First published with the title Angriff der ISombies by Karsten Krepinsky/Neuwelt Verlag.

Cover design by Ingo Krepinsky, Die TYPONAUTEN

www.typonauten.de/eng

Published by Dr. Karsten Krepinsky

Berlin, October 2021

All rights reserved.

No part of this e-book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior written permission of the author.

www.karstenkrepinsky.de

About this Book

Zombies have launched an attack on Berlin, slaughtering anyone who gets in their way. While politicians run for cover, a mismatched group of young outcasts stands up to the challenge…

Absolutely non-PC. A subversive Zombie satire.

Warning!

Reading this Zombie Apocalypse might trigger PC anxiety in sensitive people, making comprehensive brain restructuring surgery unavoidable.

For people who don’t go with the flow.

Map of Berlin

You should recognize them by their deeds, not by their words.

1. John 2, 1-6

1.

The fire of loathing is burning hot inside me when I direct my steps toward the awe-inspiring stone structure—the heart of a country that once was my country, too. Something is driving my twitching body onward with the irresistible urge to sink my teeth into human flesh. The national flag is blowing in the wind. Sunlight, reflected in a dome of glass. Wisps of smoke, spiraling high into the skies. My mind has finally given up trying to control my body. It was a hard struggle, but in the end a higher power won out. I now know that I can turn them all. I’m nothing but a vessel, destined to pass on the seed I carry inside of me. For the rise of a new society. “To the German People” I read the inscription above the entrance portal, before my senses finally take leave of me and the parasites grabs hold of the wheel.

2.

One day earlier

Berlin, September 24

Schloss Bellevue, Office of the President of the Federal Republik of Germany

President Deutsch sat at his desk, golden fountain pen in hand, having just deleted the last sentence he had written.

Globalization is a chance, albeit a choice wrought with risks.

Somehow this didn’t sound like the right beginning of a ground-breaking speech, meant to secure him a place in the history books. He knew what was at stake, of course, during this fateful epoch his country was going through. Therefore, this speech needed to be nothing less but his legacy to his people. It simply had to leave a lasting impression, following in the tradition of his otherwise rather unlucky predecessor, whose casual remark about the new import-religion in this country had made some waves. Not an easy feat, the President thought, as the Chancellor had even gone a step further by refusing to set a limit for the number of asylum-seekers allowed in. What was left for Deutsch to say to make him the darling of the press and entice those journos to sing his praise as the intellectual and humanist he aspired to be? He stood, planted his palms on the desk, struck a position befitting a head of state, and presented his less-than-aquiline three-quarter view to the gilded mirror. The intercom buzzed and his secretary announced that his Undersecretary, Michael Mustermann, wished to see him. Why not? the President thought with a complacent smile, pressing the intercom button. “Just show him in.” Maybe his flunky would come up with a brilliant suggestion for his speech.

Mustermann stopped in the door with a slight bow and then proceeded toward the desk in an unusual hasty manner. “We need to evacuate Bellevue at once,” he burst out, his voice shrill, yes, almost hysterical. One hand fumbled, testing the state of his comb-over.

“What?” the president asked, sounding less surprised than annoyed due to his lackey’s strident tones.

“There’s fighting in Kreuzberg and Wedding.”

“Fighting? What are you talking about? A Russian invasion?”

“The helicopter is scheduled to land in the yard in ten minutes sharp,” Mustermann ignored his superior’s question.

“But… now is not… and what about our annual reception for the members of the press? You must be joking, old boy.”

“The reception has to… it can’t… I… I don’t see any other option.”

The President touched his index finger to his lip. “And if we moved the reception to Bonn?” he asked with a wide smile, looking proud as if expecting applause for his presence of mind.

“The helicopter. Don’t you see?” Mustermann insisted.

The President waved him off. “A man is bound to his duties even in turbulent times, and you are surely aware of what a President’s duties entail. He is the Representative of his country. And therefore it has to be our foremost priority having Werner come here at once,” Deutsch chided Mustermann. “A great photographer, this man,” he added. “He did fabulous portraits of me at the last reception. From the front upward and with a slight angle.” The President proceeded to admire his own reflection in the mirror. “I even took up ballroom-dancing to raise to the occasion. No one will steal my show this time. And, by the way, the President of the United States has set aside half an hour just for me alone. I’ve looked up the protocols: No American leader ever has spent so much time with his German counterpart.”

“But the helicopter…” Mustermann almost lost control over his features, a lapse which, however, was made impossible by the fact, that his facial repertoire only made two variants available. The dozens of muscles, shaping the human face into the different expressions that reflected a person’s state of mind, just seemed to have two versions on stock. Number one, employed whenever Mustermann felt nervous, under attack, or genuinely happy—or also while professing love to his wife, an incident that, in all likelihood, hadn’t occurred for the last two decades – resembled an inane failing-to-be-ironic grin. Number two could have been mistaken for the shocked stare of a schoolboy who had just been caught cheating during an exam. The last time the world had been exposed to variant number two was four years ago when Mustermann’s party had awarded him with the position of Undersecretary.

“Keep your hair on, old boy.” The President’s laugh turned into a little cough. “The bird won’t take off without me.” He walked around his desk and put a hand on his Undersecretary’s shoulder. “Why don’t you start packing my personal things?”

“Yes, sir,” Mustermann said with a subservient bow.

“I’ll go ahead to the helicopter,” Deutsch continued, his lips pursed, walking out of his office with measured steps and only speeding up after he could be sure that Mustermann wasn’t watching. Mustermann picked up the briefcase from under the floor lamp and hurried over to the desk, where he started to empty the first top drawers. On a final note he also stuffed a tube of hair gel and both combs into the case. When he walked out of the office, the secretary at the front desk had already left. Making his way through the empty corridors of Schloss Bellevue, he heard nothing but the hollow sound of his footsteps. He found it odd, that there was no one waiting for him. He pushed through the double front doors, where the helicopter was parked in the middle of a flower bed, its rotor already in motion.

“Your things!” Mustermann called, holding out the case. But the pilot ignored him, revving up the engine, and soon the helicopter was airborne. While Mustermann slowly came down the front steps, the machine soared up into the sky. An armored government car shot down the gravel path crossing the grounds of Bellevue, raced out into the street, and disappeared, tires squealing, in the direction of Tiergarten. Soon, there was nobody left but a lone gardener, who at least seemed to take notice of Mustermann’s existence. He approached him, hoe in hand and a little wobbly on his feet. Mustermann wondered about the man’s disheveled appearance. It must have been a hard day’s work, he concluded, because the gardener was also white as a sheet and his eyes looked sunken in his face. Mustermann noticed neither the gaping wound on the gardener’s neck nor the madness in the man’s eyes, who was assessing him, obviously setting on him as his next victim. Mustermann just wanted to be nice. He smiled, holding out his hand for a shake. The gardener dropped his hoe and slowly lifted his hat, as if to salute him. An oddly bulbous protrusion on his forehead came into view. Writhing and pumping, a dark mass was twitching behind almost translucent skin. The overall impression was definitely off-putting. Mustermann let his hand sink. His case tumbled from his suddenly limp fingers onto the gravel. The gardener’s eyes rolled back in his head. He grabbed Mustermann by the shoulders, sinking his teeth into the Undersecretary’s neck. Locked in the gardener’s vise-like grip, Mustermann dropped to the ground like a felled tree.

3.

Two hours earlier

Kreuzberg, elevated track of the subway line U1

Frank had been a student of biology at the Freie Universität Berlin for two semesters now. As he lived in Friedrichshain, he always took the U1 from its final stop at Warschauer Strasse across River Spree and from there all the way through Kreuzberg. Before it reached the triangular junction, the U1 moved along on an elevated track, supported by columns of steel, that ran between the buildings at third-floor level. “Gründerzeit”-style apartment houses, modern concrete blocks, and the occasional place of worship zoomed past the window without leaving Frank with a lasting impression. Eyes half closed and still fighting stupor after last night’s party, he was slumped on a bench in the first car. He was dressed all in black and, with his hoodie and worn-out Doc Martens, liked to imagine himself as something of an urban rebel. An outcast who always sat in the last row on the bus, keeping his distance to the rest of humanity, watching and ever ready to deliver a cynical barb when the mood hit him. Frank had no idea what to do with his life. For reasons even unknown to himself, he had enrolled in biology a year ago, a decision he since regretted. Sadly, he wasn’t of the stuff geniuses were made of. Yes, he had rated with an IQ of 167, but it had just been an online test conducted by himself, and he had needed two attempts to make the score. To hell with it, he thought. He took a pack of Aspirins from his pocket, squeezed a pill out of the blister foil, chewed, and dry-swallowed. Antithrombin deficiency. Thick blood, was the popular name of this condition, with the unfortunate tendency to coagulate. A genetic defect, which meant that he needed three pills of this blood thinner a day to prevent thrombosis.

The pill’s aftertaste lingering in his mouth, Frank let his eyes roam. At this time of the day, it was a little after eleven a.m., the train wasn’t very full. Most commuters were already at their jobs, which meant that he had to share the ancient narrow-gauge car with only three other people: a muscular working-class hero wearing blue coveralls, a natty Turkish guy, and a female student. The fact that they all seemed to be in their early twenties was the only thing they had in common. The woman Frank had already met. Her name was Sophia, a fellow student in the same year and an activist in the university’s student association. Last semester’s blue bag, sporting a huge pin with the legend “Refugees Welcome”, had meanwhile been replaced by a satchel made of some kind of green and white checkered material with a tatty fringe. “Go Vegan!” its legend declared. Every semester seemed to call for its own slogan, Frank thought. A Che-Guevara pin and a sew-on rainbow flag completed the left-wing uniform. For Frank she was Political Correctness personified, spouting slogans and phrases without ever having aspired to a view of her own. One of those people who claimed that gender and ethnic background didn’t make a difference, which, however, didn’t stop them from constantly sectionalizing and evaluating the world according to categories only known to them. Activists like her, he thought, were the grave-diggers of critical discourse, always coming up with new taboos and insisting that certain things had better be left unsaid. Dogmatists, who were just full of themselves, and cookie-cutter anarchists, as far as Frank was concerned. They dealt with language in an Orwellian fashion, with the result that discrimination continued to take place in people’s minds, but could not be called by its name any longer.

Frank gave Sophia the stink eye. Their aversion was mutual. When entering the train at Schlesisches Tor, Sophia had recognized him at once, veered away, and had hurried to the other end of the car. While he was an outcast, Frank mused, Sophia was definitely the cheerleading-type. The epitome of the quarterback’s blonde girlfriend, albeit, with her dreadlocks and her artfully distressed jeans, a tree-hugging German version.

The sturdy stubble-headed workman groaned and started waving his hand-held gaming console from left to right. He must have slammed his formula-one bolide into some concrete pillar, Frank thought. This six-three, three-hundred-pounds behemoth to him was nothing but ignorance and feeble-mindedness come alive. Millions of years of evolution, come to a screeching halt. Darwin must have gotten it wrong somehow, Frank decided. Survival of the fittest, what a joke! This tub of lard probably found fulfillment in pickling his last ounces of brains in beer, when he wasn’t busy jerking off in some port-a-john. The world was going to the dogs anyhow, for Frank there was no doubt about it. Because, hey, who was up to the job of saving it? The Turkish guy at the door maybe, who seemed to be fascinated studying his perfectly manicured nails? He looked like someone who worked as a coiffeur in the hip neighborhood of Prenzlauer Berg, giggling and blowing air-kisses to his gay friends, while he fooled around with the hair of some silly broad.

The train had been sitting at the platform of Hallesches Tor for over five minutes now. Sophia stood and impatiently walked to the front exit. When she pressed the button, the doors wouldn’t budge.

“Any idea what’s going on here?” Sophie addressed the Turkish guy.

“Probably a blown signal, like,” he replied, the picture of ennui. “It won’t be long.”

“You have a signal?” She pointed to her phone.

The Turk swiped long tresses of hair off his face and took out his smartphone.