Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

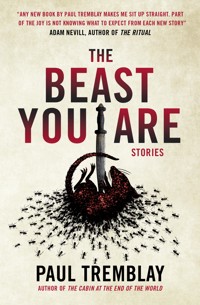

A haunting collection of short fiction from the bestselling author of The Pallbearers Club, A Head Full of Ghosts, and The Cabin at the End of the World. Paul Tremblay has won widespread acclaim for illuminating the dark horrors of the mind in novels and stories that push the boundaries of storytelling itself. The fifteen pieces in this brilliant collection, The Beast You Are, are all monsters of a kind, ready to loudly (and lovingly) smash through your head and into your heart. In "The Dead Thing," a middle-schooler struggles to deal with the aftermath of her parents' substance addictions and split. One day, her little brother claims he found a shoebox with "the dead thing" inside. He won't show it to her and he won't let the box out of his sight. In "The Last Conversation," a person wakes in a sterile, white room and begins to receive instructions via intercom from a woman named Anne. When they are finally allowed to leave the room to complete a task, what they find is as shocking as it is heartbreaking. The title novella, "The Beast You Are," is a mini epic in which the destinies and secrets of a village, a dog, and a cat are intertwined with a giant monster that returns to wreak havoc every thirty years. A masterpiece of literary horror and psychological suspense, The Beast You Are is a fearlessly imagined collection from one of the most electrifying and innovative writers working today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 481

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

ICE COLD LEMONADE 25¢HAUNTED HOUSE TOUR: 1 PER PERSON

MEAN TIME

I KNOW YOU’RE THERE

THE POSTAL ZONE: THE POSSESSION EDITION

RED EYES

THE BLOG AT THE END OF THE WORLD

THEM: A PITCH

HOUSE OF WINDOWS

THE LAST CONVERSATION

MOSTLY SIZE

THE LARGE MAN

THE DEAD THING

HOWARD STURGIS AND THE LETTERS AND THE VAN AND WHAT HE FOUND WHEN HE WENT BACK TO HIS HOUSE

THE PARTY

THE BEAST YOU ARE

STORY NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PUBLICATION HISTORY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

THE BEAST YOU ARE

Also by Paul Tremblay and available from Titan Books

Disappearance at Devil’s Rock

A Head Full of Ghosts

The Cabin at the End of the World

Growing Things and Other Stories

Survivor Song

The Little Sleep and No Sleep Till Wonderland Omnibus

The Pallbearers Club

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Beast You Are: Stories

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364278

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364285

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Crows for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Healing,” (written by James Cox) courtesy of Bad Vibrations Records © 2022.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2023 Paul Tremblay. All rights reserved.

Paul Tremblay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Lisa, Cole, and Emma

Life is no way to treat an animal.

—KURT VONNEGUT, A Man Without a Country

And I’ll rip a lump out of my throat, using my teeth.

—CROWS, “Healing”

ICE COLD LEMONADE 25¢ HAUNTED HOUSE TOUR: 1 PER PERSON

I was such a loser when I was a kid. Like a John-Hughes-Hollywood-’80s-movie-typecast loser. Maybe we all imagine ourselves as being that special kind of ugly duckling, with the truth being too scary to contemplate: maybe I was someone’s bully or I was the kid who egged on the bullies screaming, “Sweep the leg!” or maybe I was lower than the Hughes loser, someone who would never be shown in a movie.

When I think of who I was all those years ago, I’m both embarrassed and look-at-what-I’ve-become proud, as though the distance spanned between those two me’s can only be measured in light-years. That distance is a lie, of course, though perhaps necessary to justify perceived successes and mollify the disappointments and failures. That thirteen-year-old me is still there inside: the socially awkward one who wouldn’t find a group he belonged to until college; the one who watched way too much TV and listened to records while lying on the floor with the speakers tented over his head; the one who was afraid of Jaws appearing in any body of water, Christopher Lee vampires, the dark in his closet and under the bed, and the blinding flash of a nuclear bomb. That kid is all too frighteningly retrievable at times.

Now he’s here in a more tangible form. He’s in the contents of a weathered cardboard box sitting like a toadstool on my kitchen counter. Mom inexplicably plopped this time capsule in my lap on her way out the door after an impromptu visit. When I asked for an explanation, she said she thought I should have it. I pressed her for more of the why and she said, “Well, because it’s yours. It’s your stuff,” as though she were weary of the burden of having had to keep it for all those years.

Catherine is visiting her parents on the Cape, and she took my daughter, Izzy, with her. I stayed home to finish edits (which remain stubbornly unfinished) on a manuscript that was due last week. Catherine and Izzy would’ve torn through this box-of-me right away and laughed themselves silly at the old photos of my stick-figure body and my map of freckles and crooked teeth, the collection of crayon renderings of dinosaurs with small heads and ludicrously large bodies, and the fourth-grade current events project on Ronald Reagan for which I’d earned a disappointing C+ and a demoralizing teacher comment of “too messy.” And I would’ve reveled in their attention, their warm spotlight shining on who I was and who I’ve become.

I didn’t find it until my second pass through the box, which seems impossible, as I took care to peel old pictures apart and handle everything delicately as one might handle ancient parchments. That second pass occurred two hours after the first, and there was a pizza and multiple beers and no edits in between.

The drawing that I don’t remember saving was there at the bottom of the box, framed by the cardboard and its interior darkness. I thought I’d forgotten it; I know I never had.

The initial discovery was more confounding than dread-inducing, but hours have passed and now it’s late and it’s dark. I have every light on in the house, which only makes the dark outside even darker. I am alone and I am on alert and I feel time creeping forward (time doesn’t run out; it continues forward and it continues without you). I do not sit in any one room for longer than five minutes. I pass through the lower level of the house as quietly as I can, like an omniscient, emotionally distant narrator, which I am not. On the TV is a baseball game that I don’t care about, blaring at full volume. I consider going to my car and driving to my in-laws’ on the Cape, which would be ridiculous, as I wouldn’t arrive until well after midnight and Catherine and Izzy are coming home tomorrow morning.

Would it be so ridiculous?

Tomorrow when my family returns home and the windows are open, the sunlight as warm as a promise, I will join them in laughing at me. But it is not tomorrow and they are not here.

I am glad they’re not here. They would’ve found the drawing before I did.

* * *

I rode my bicycle all over Beverly, Massachusetts, the summer of 1984. I didn’t have a BMX bike with thick, knobby tires made for ramps and wheelies and chewing up and spitting out dirt and pavement. Mine was a dinged up, used-to-belong-to-my-dad ten-speed, and the only things skinnier and balder than the tires were my arms and legs. On my rides I always made sure to rattle by Kelly Bishop’s house on the off-off-chance I’d find her in her front yard. Doing what? Who knows. But in those fantasies she waved or head-nodded at me and she would ask what I was doing and I’d tell her all nonchalant-like that I was just passing through, on my way back home, even though she’d have to know her dead-end street two blocks west and one block north from where I lived on the daredevil-steep Echo Ave hill wasn’t on my way home, which was presuming she even knew where I lived. All such details were worked out or inconsequential in fantasies, of course.

One afternoon it seemed a part of my fantasy was coming true when Kelly and her little sister were at the end of their long driveway, sitting at a small fold-up table with a pitcher of lemonade. I couldn’t bring myself to stop or slow down or even make more than glancing eye contact. I had no money for lemonade, therefore I had no reason to stop. Kelly shouted at me as I rolled by. Her greeting wasn’t a “Hey there” or even a “Hi,” but instead, “Buy some lemonade or we’ll pop your tires!”

After twenty-four hours of hopeful and fearful Should I or shouldn’t I?, I went back the next day with a pocket full of quarters. Kelly was again stationed at the end of her driveway. My brakes squealed as I jerked to an abrupt and uncoordinated stop. My rusted kickstand screamed with You’re really doing this? embarrassment. The girls didn’t say anything and watched my approach with a mix of disinterest and what I imagined to be the look I gave ants before I squashed them.

They sat at the same table setup as the previous day, but there was no pitcher of lemonade. Never afraid to state the obvious, I said, “So, um, no lemonade today?” The fifty cents clutched in my sweaty hand might as well have melted.

Kelly said, “Lemonade was yesterday. Can’t you read the sign?” She sat slumped in her beach chair, a full-body eye roll, and her long, tanned legs spilled out from under the table and the white poster-board sign taped to the front. She wore a red Coke T-shirt. Her chestnut-brown hair was pulled and tied into a side high ponytail. Kelly was clearly well into her pubescent physical transformation, whereas I was still a boy, without even a shadow of hair under my armpits.

Kelly’s little sister with the bowl-cut mop of dirty blond hair was going to be in second grade; I didn’t know her name and was too nervous to ask. She covered her mouth, fake-laughed, and wobbled like a penguin in her unstable chair. That she might topple into the table or to the blacktop didn’t seem to bother Kelly.

“You’re supposed to be the smart one, Paul,” Kelly added.

“Heh, yeah, sorry.” I left the quarters in my pocket to hide their shame and adjusted my blue gym shorts; they were too short, even for the who-wears-short-shorts ’80s. I tried to fill the chest of my NBA CHAMPS Celtics T-shirt with deep breaths, but only managed to stir a weak ripple in that green sailcloth.

Their updated sign read:

Ice Cold Lemonade 25¢Haunted House Tour: 1 Per Person

Seemed straightforward enough, but I didn’t know what to make of it. I feared it was some kind of a joke or prank. Were Rick or Winston or other jerks hiding close by to jump out and pants me? I thought about hopping back on my bike and getting the hell out before I did something epically cringeworthy Kelly would describe in detail to all her friends and, by proxy, the entire soon-to-be seventh-grade class.

Kelly asked, “Do you want a tour of our creepy old house or not?”

I stammered and I sweated. I remember sweating a lot.

Kelly told me the lemonade-stand thing was boring and that her new haunted-house-tour idea was genius. I would be their first to go on the tour, so I’d be helping them out. She said, “We’ll even only charge you half price. Be a pal, Paulie.”

Was Kelly Bishop inviting me into her house? Was she making fun of me? The “be a pal” bit sounded like a joke and felt like a joke. I looked around the front yard, spying between the tall front hedges, looking for the ambush. I decided I didn’t care, and said, “Okay, yeah.”

The little sister shouted, “One dollar!” and held out an open hand.

Kelly corrected her. “I said ‘half-price.’”

“What’s half?”

“Fifty cents.”

Little Sis shouted, “Fifty cents!” her hand still out.

I paid, happy to be giving the sweaty quarters to her and not Kelly.

I asked, “Is it scary, I mean, supposed to be scary?” I tried smiling bravely. I wasn’t brave. I still slept with my door open and the hallway light on. My smile was pretend brave, and it wasn’t much of a smile, as I tried not to show off my mouth of metal braces, the elastics on either side mercifully no longer necessary as of three weeks ago.

Kelly stood and said, “Terrifying. You’ll wet yourself and be sucking your thumb for a week.” She whacked her sister on the shoulder and commanded, “Go. You have one minute to be ready.”

“I don’t need a minute.” She bounced across the lawn onto the porch and slammed the front door closed behind her.

Kelly flipped through a stack of notecards. She said she hadn’t memorized the script yet, but she would eventually.

I followed her down the driveway to the house I never thought of as scary or creepy but now that it had the word “haunted” attached to it, even in jest . . . it was kind of creepy. The only three-family home in the neighborhood, it looked impossibly tall from up close. And it was old, worn out, the white paint peeling and flaking away. Its stone-and-mortar foundation appeared crooked. The windows were tall and thin and impenetrable. The small front porch had two skeletal posts holding up a warped overhang that could come crashing down at any second.

We walked up the stairs to the porch, and the wood felt soft under my feet. Kelly was flipping through her notecards and held the front screen door open for me with a jutted-out hip. I scooted by, holding my breath, careful to not accidentally brush against her.

The cramped front hallway/foyer was crowded with bikes and shovels and smelled like wet leaves. A poorly lit staircase curled up to the right. Kelly told me that the tour finishes on the second floor and we weren’t allowed all the way upstairs to the third, and, somewhat randomly, that she wrote “one per person” on the sign so that no pervs would try for repeat tours since she and her sister were home by themselves.

“Your parents aren’t home?” My voice cracked, as if on cue.

If Kelly answered with a nod of the head, I didn’t see it. She reached across me, opened the door to my left, and said, “Welcome to House Black, the most haunted house on the North Shore.”

Kelly put one hand between my shoulder blades and pushed me inside to a darkened kitchen. The linoleum was sandy, gritty under my shuffling sneakers. The room smelled of dust and pennies. The shapes of the table, chairs, and appliances were sleeping animals. From somewhere on this first floor, her sister gave a witchy laugh. It was muffled and I remember thinking it sounded like she was inside the walls.

Kelly carefully narrated a ghost story: The house was built in the 1700s by a man named Robert or Reginald Black, a merchant sailor who was gone for months at a time. His wife, Denise, would dutifully wait for him in the kitchen. After all the years of his leaving, Denise was driven mad by a lonely heart, and she wouldn’t go anywhere else in the house but the kitchen until he returned home. She slept sitting in a wooden chair and washed herself in the kitchen sink. Years passed like this. Mr. Black was to take one final trip before retiring but Mrs. Black had had enough. As he ate his farewell breakfast she smashed him over the head with an iron skillet until he was dead. Mrs. Black then stuffed her husband’s body into the oven.

The kitchen’s overhead light, a dirty yellow fixture, turned on. I saw a little hand leave the switch and disappear behind a door across the room from me. On top of the oven was a black cast-iron skillet. Little Sis flashed her arm back into the room and turned out the light.

Kelly loomed over me (she was at least three inches taller) and said that this was not the same oven, and everyone who ever lived here has tried getting a new one, but you can still sometimes hear Mr. Black clanging around inside.

The oven door dropped open with a metal scream, like when an ironing board’s legs were pried open.

I jumped backward and knocked into the kitchen table.

Kelly hissed, “That’s too hard, be careful! You’re gonna rip the oven door off!”

Little Sis dashed into the room, and I could see in her hands a ball of fishing line, which was tethered to the oven door handle.

Kelly asked me what I thought of the tour opener, if I found it satisfactory. I swear that is the phrasing she used.

Mortified that I’d literally jumped and sure that she could hear my heart rabbiting in my chest, I mumbled, “Yeah, that was good.”

The tour moved on throughout the darkened first floor. All the see-through lace curtains were drawn, and either Kelly or Little Sis would turn a room’s light on and off during Kelly’s readings. Most of the stories featured the hapless descendants of the Blacks. The dining room’s story was unremarkable, as was the story for the living room, which was the largest room on the first floor. I’d begun to lose focus on the tour and let my mind wander to Kelly and what she was like when her parents were home and then, perhaps oddly, what her parents were like, and if they were like mine. My dad had recently moved from the Parker Brothers factory to managing one of their warehouses, and Mom worked part-time as a bank teller. I wondered what Kelly’s parents did for work and if they sat in the kitchen and discussed their money problems too. Were her parents kind? Were they too kind? Were they overbearing or unreasonable? Were they perpetually distracted? Did they argue? Were they cold? Were they cruel? I still wonder these things about everyone else’s parents.

Kelly did not take me into her parents’ bedroom, saying simply “Under construction” as we passed by the closed door.

I suggested that she make up a story about something or someone terrible kept hidden behind the door.

Kelly to this point had kept her nose in her script cards when not watching for my reaction and jotting down notes with a pencil. Her head snapped up at me and she said, “None of these are made-up stories, Paul.”

There was another bedroom, the one directly off the kitchen, and it was being used as an office/sitting room. There was a desk and bookcases tracing the walls’ boundaries. The walls were covered in brownish-yellow wallpaper and the circular throw rug was dark too; I do not remember the colors. It’s as though color didn’t exist there. The room was sepia, like a memory. In the middle of the room was a rolling chair, and on the chair was a form covered by a white sheet.

Kelly had to coax me into the room. I kept a wide berth between me and the sheeted figure, knowing the possibility that there was someone under there waiting to jump out and grab me. Though the closer I got, it wasn’t uniform, and the proportions were all off. It wasn’t a single body; the shape was comprised of more shapes.

Kelly said that the ghost of a man named Darcy Dearborn (I remember his alliterative name) haunted this room. A real-estate mogul, he purchased the house in 1923. He lost everything but the house in the 1929 stock-market crash and was forced to rent the second and third floors out to strangers. He took to sitting in this room and listening to his tenants above walking around, going about their day. Kelly paused at this point of the story and looked up at the ceiling expectantly. I did too. Eventually we could hear little footsteps running along the second floor above us. The running stopped and became loud thuds. Little Sis was jumping up and down in place, mashing her feet into the floor. Kelly said, “She’s such a little shit,” shook her head, and continued with the tale. Darcy, much like Mrs. Black from all those years before, became housebound and wouldn’t leave this room. Local family and neighbors bought his groceries for him and took care of collecting his rent checks and banking and everything else for him, until one day they didn’t. Darcy stayed in the room and in his chair, and he died and no one found him until years later and he’d almost completely decomposed and faded away. His ghost shuts the doors to the office when they are open.

The door to the kitchen behind opened and shut.

I remember thinking the Darcy story had holes in it. I remember thinking it was too much like the first Mrs. Black story, which muted its impact. But then I became paranoid that Kelly had tailored these stories for me somehow. Was she implying that I was doomed to be a loner, a shut-in, because I stayed home by myself too much? I had one new friend I’d met in sixth grade, but he lived in North Beverly and spent much of his summer in Maine and I couldn’t go see him very often. I wasn’t friends with anyone in my neighborhood. That’s not an exaggeration. Throughout that summer, particularly if I’d spent the previous day watching TV or shooting hoops in the driveway by myself, Mom would give me an errand (usually sending me down the street to the White Hen Pantry convenience store to buy her a pack of cigarettes—you could do that in the ’80s) and then tell me to invite some friends over. She never mentioned any kids by name because there were no kids to mention by name. I told her I would but would then go ride my bike instead. That was good enough for Mom, or maybe it wasn’t and she knew I wasn’t really going to see or play with anyone. Mom now still reacts with an unbridled joy that comes too close to open shock and surprise when she hears of my many adult friends.

I envisioned myself becoming a sun-starved, Gollum-like adult, cloistered in my sad bedroom at home until Kelly led me out of the first-floor living space to the cramped and steep staircase. The stairs were a dark wood with a darker stair tread or runner. The walls were panels or planks of the same dark wood. I was never a sailor like Mr. Black, but it was easy to imagine that we were climbing up from the belly of a ship.

Kelly said that a girl named Kathleen died on the stairwell in 1937. Kathleen used to send croquet balls crashing down the stairs. Her terrible father with arms and hands that were too long for his body got so sick of her doing it, he snuck up behind her and nudged her off the second-floor landing. She fell and tumbled and broke her neck and died. There was an inquest, and her father was never charged. However, his wife knew her husband was lying about not being responsible for Kathleen’s death, and the following summer she poisoned him and herself while picnicking at Lynch Park. At night you can hear Kathleen giggling (Kelly’s sister obliged from above at that point in the tale) and the rattles and knocks of croquet balls bouncing down the stairs. And if you’re not holding the railing, you’ll feel those cold, extra-large hands push you or grab your ankles.

I wasn’t saying much of anything in response at this point and was content to be there with Kelly, knowing I would likely never spend this much time alone with her again. I was scared, but it was the good kind of scared because it was shared if not quite commiserative.

The second-floor landing was bright with sunlight pouring through the uncovered four-paned window next to the second floor’s front door. It was only then that I realized each floor was constructed as separate apartments or living spaces, and since I hadn’t seen their rooms downstairs, it meant that Kelly’s and her sister’s bedrooms must be here upstairs, away from her parents’ bedroom. I couldn’t imagine sleeping that far away from my parents, and future live-at-home-shut-in or not, I felt bad for her and her sister.

Inside there was a second kitchen that was bright and sparkled with disuse. The linoleum and cabinets were white. I wondered (but didn’t ask) if the two of them ate up here alone for breakfast or at night for dinner, and I again thought about Kelly’s parents and what kind of people would leave them alone in the summer and essentially in their own apartment.

The tour didn’t linger in the kitchen, nor did we stop in what she called the playroom, which had the same dimensions as the dining room below on the first floor. Perhaps she didn’t want to make their playroom a scary place.

We went into her sister’s room next. I only remember the pink wallpaper, an unfortunate shade of Pepto Bismol, and the army of stuffed animals staged on the floor and all facing me. There were a gaggle of teddy bears and a stuffed Garfield and a Pink Panther and a rat wearing a green fedora and a doe-eyed brontosaurus and more, and they all had black marble eyes. Kelly said, “Oops,” and turned off the overhead light.

The story for this room was by far the most gruesome.

John and Genie Graham bought the house in 1952 and they had a little boy named Will. To make ends meet the family rented the top two floors to strangers. The stranger on the second floor was named Gregg with two g’s, and the third-floor tenant was named Rolph, not Ralph. Very little is known about the two men. For the two years of the Gregg with two g’s and Rolph occupancy, Will would periodically complain he couldn’t find one of his many stuffed-animal companions and insisted that someone stole it. He had so many stuffed animals that with each individual complaint his parents were sure the missing animal was simply misplaced or kicked under the bed or he’d taken it to the park and left it behind. Then there were locals who complained that Rolph wasn’t coming to work anymore and wasn’t seen at the grocery store or the bar he liked to go to, and that he, too, was misplaced. Then there was a smell coming from the second floor, and they initially feared a critter had died in the walls, and then those fears became something else. When Mr. and Mrs. Graham entered the second-floor apartment with the police, Gregg with two g’s was nowhere to be found. But they found Will’s missing stuffed animals. They were all sitting in this room like they were now, and they were bloodstained and tattered and they smelled terribly. Hidden within the plush hides of the stuffed animals were hacked-up pieces of Rolph, the former third-floor tenant. There were rumors of Gregg with two g’s living in Providence and Fall River and more alarmingly close by in Salem, but no one ever found him. Kelly said that stuffed animals in this house go missing and then reappear in this bedroom by themselves, congregating with one another in the middle of the floor on their own, patiently waiting for their new stuffing.

“That’s a really terrible story,” I said in a breathless way that meant the opposite.

“Paul! It’s not a story,” Kelly said, but she looked at me and smiled. I’ll not describe that look or that smile beyond saying I’ll remember both (along with a different look from her, one I got a few months after the tour), for as long as those particular synapses fire within my brain.

Kelly led me to a final room, her bedroom in the back of the house. The room was brightly lit; shades pulled up and white curtains open. Her walls were white and might’ve been painted over clapboard or paneling and decorated with posters of Michael Jackson, Duran Duran, and other musicians. There was a clothes bureau that seemed to have been jigsawed together using different pieces of wood. Its top was a landfill of crumpled-up notes, used candy wrappers, loose change, barrettes, and other adolescent debris. At the foot of her bed was a large chest covered by an afghan. On walls opposite of each other were a small desk and a bookcase that was half-full with books, the rest of the space claimed by dolls and knickknacks. The floor was hardwood and there was a small baby-chick-yellow rectangular patch of rug by her bed, which was flush against the wall and under two windows overlooking the backyard.

Kelly didn’t say anything right away, and I stared at everything but her, more nervous to be in this room than any other. I said, “You have a cool room.” I might’ve said “nice” instead of “cool,” but God, I hope I didn’t.

I don’t remember if Kelly said thanks or not. She pocketed her notecards, walked ahead of me, sat on the rug, and faced her bed. She said, “I dream about it every night. I wish it would stop.”

I hadn’t noticed it until she said what she said. There was a sketch propped up by a bookend on the middle of her bed. I sat down next to Kelly. I asked, “Did you draw that?”

She nodded and didn’t look at me. She didn’t even look at me when I was staring at her profile for what felt like the rest of the summer. Then I, too, stared at the drawing.

The left side of its cartoonish head was misshapen, almost like a bite had been taken out, and the left eye was missing. Its right eye was round and blackened by slashes instead of a pupil. The mouth was a horrible band of triangular teeth spanning the horizontal circumference. Three strips of skin stretched from the top half of the head over the mouth and teeth and wrapped under its chin. What appeared to be a forest of wintered branches stuck out from all over its head. The wraithlike body was all angles and slashes, and the arms were elongated triangles reaching out. It had no legs. The jagged bottom of its floating form ended in larger versions of its shark teeth.

There are things I of course don’t remember about that day in Kelly’s house and many other things I’m sure I’ve embellished (though not purposefully so). But I remember when I first saw the drawing and how it made me feel. While this might sound like an adult’s perspective, I’m telling you that this was the first time I realized or intellectualized that I would be dead someday. Sitting on the bedroom floor next to the cute girl of my adolescent daydreams, I looked at the drawing and imagined my death, the final closing of my eyes and the total and utter blankness and emptiness of . . . I could only think of the phrase “not-me.” The void of not-me. I wondered if the rest of my life would pass like how summer vacations passed—would I be about to die and asking How did it all go so quickly? I wondered how long and what part of me would linger in nothingness and if I’d feel pain or cold or anything at all, and I tried to shake it all away by saying to Kelly, “Wow, that’s really good.”

“Good?”

“The drawing. Yeah. It’s good. And creepy.”

Kelly didn’t respond, but I was back inside her sunny bedroom and sitting on the floor instead of lost inside my own head. I asked and pointed, “What are the things sticking out? They look like branches.”

She told me she tried to make up a story for this ghost, like maybe the kid who lived in the house before Kelly did was sneaking around peeking into houses and sometimes stealing little things and bits no one would miss (like a thumbtack or an almost-used-up spool of red thread) and she got caught by someone and was chased and in desperation she ran behind her house and she got stuck or trapped in the bushes and she died within sight of her big old ratty house. But that didn’t feel like the true story, or the right story. It certainly wasn’t the real reason for the ghost.

Kelly told me this ghost appeared in her dreams every night. The dreams varied, but the ghost was always the same ghost. Sometimes she was not in her body and she witnessed everything from a remove, like she was a movie camera. Most times Kelly was Kelly and she saw everything through her own eyes. The most common dream featured Kelly alone in a cornfield that had already been cut and harvested. Dark, impenetrable woods surrounded the field on all sides. She heard a low voice laughing, so low it was a hanging kind of laugh, but then it was also high-pitched, so it was both at the same time. (She said “both at the same time” twice.) Her heart beat loud enough that she thought it was the full moon thumping down at her, giving her a Morse code message to run. Even though she was terrified, she ran into the woods because it was the only way to get back to her house. She ran through the forest and night air as thick as paint, and she got close to her backyard and she could see her house, but no lights were on, so it was all in shadow and looked like a giant tombstone. Then the ghost came streaming for her from the direction of the house and she knew her house was a traitor because it was where the ghost stayed while it patiently waited for this night and for Kelly. It was so dark, but she could see the ghost and its horrible smile bigger than that heartbeat moon. And the dream ended the same way every time.

“I hear myself scream, but it sounds far away, like I’m below, in the ground, and then I die. I remember what it feels like to die until I wake up, and then it fades away, but not all the way away,” Kelly said. She rocked forward and back and rubbed her hands together, staring at the drawing.

The ceiling above us creaked and groaned with someone taking slow, heavy, careful steps. Kelly’s little sister wasn’t around, and I hadn’t remembered seeing her since we got up to the second floor. I figured Sis was walking above us wearing adult-sized boots. A nice touch for what I assumed was the tour’s finale.

I said something commiserative to Kelly about having nightmares too.

She said, “I think it’s a real ghost, you know. This is the realest one. It comes every night for me. And I’m afraid maybe it’s the ghost of me.”

“Like a doppelgänger?”

Kelly smirked and rolled her eyes again, but it wasn’t as dismissive as I’m describing. She playfully hit my nonexistent bicep with the back of her hand, and despite my earlier glimpse at understanding the finality of death, I would’ve been happy to die right then. She said, “You’re the smart one, Paul, you have to tell me what that is.”

So I did. Or I gave her the close-enough general definition that the almost thirteen-year-old me could muster.

There were more footsteps on the floor above us, moving away to other rooms but still loud and creaking.

She said, “Got it. It’s kind of like a doppelgänger but not really. It’s not a future version of me, I don’t think. I think it’s the ghost of a part of me that I ignore. Or the ghost of some piece of me that I should ignore. We all have those parts, right? What if those other parts trapped inside us find a way to get out? Where do they go and what do they do? I have a part that gets out in my dreams and I’m afraid that I’m going to hear it outside of me for real. I know I am. I’m going to hear it outside of me in a crash somewhere in the house where there isn’t supposed to be, or I’ll hear it in a creak in the ceiling, and maybe I’ll even hear it walking up behind me. I don’t know if that makes any sense, and I don’t think I’m explaining it well, but that’s what I think it is.”

Little Sis burst out of Kelly’s closet and crashed dramatically onto the chest at the end of her bed, and shouted, “Boo!”

Kelly and I both were startled and we laughed, and if you’d asked me then I would’ve thought we’d been friends forever after instead of my never speaking to her again after that day.

As our laughter died out and Kelly berated her sister for scaring her, I realized that Little Sis jumped out of a closet and not from behind a door to another room that had easy access to the rest of the apartment and the stairwell to the third floor.

I said to Little Sis, “Aren’t you upstairs? I mean, that was you upstairs we heard walking around, right?”

She shook her head no and giggled, and then there were creaks and footstep tremors in the floor above us again. They were loud enough to shake dust from the walls and blow clouds in front of the sun outside.

I asked, “Who’s upstairs?”

Kelly looked at the ceiling and was expressionless. “No one is supposed to be up there. The third floor is empty. We’re going to rent it out in the fall. We’re home alone.”

I made come on and really? and you’re not joking? noises, and then in my memory—which for this brief period of time is more like a dream than something that actually happened—the continuum skips forward to me following Kelly and her sister out into the hallway and the stairwell to the third floor. Little Sis led the way and Kelly was behind me. I kept asking questions (Is this a good idea? Are you sure you want to end the tour all the way up on the third floor?) and the questions turned to poorly veiled begging, my saying that I should probably get home, we ate dinner early in my house, Mom was a worrier, et cetera. All the while I followed up the stairs and Kelly shushed me and told me to be quiet. The stairwell thinned and squeezed and curled up into a small landing, or a perch. An eave intruded into the headspace to the left of the third-floor apartment’s door. The three of us sardined onto that precarious landing that felt like a cliff. There was no more discussion and Little Sis opened the door, deftly skittered aside, and like she had on the first floor, Kelly two-handed shoved me inside.

This apartment was clearly smaller than the first two, with the A-frame roof slanting the ceilings, intruding into the living space. I stepped into a small, gray kitchen that smelled musty from disuse. Directly across the room from me was a long, dark hallway. It was as though the ceilings and their symmetrical slants were constructed with the sole purpose of focusing my stare into this dark tunnel. There wasn’t a hallway like this in either of the other apartments; the third-floor layout was totally different, and the thought of wandering about with no idea of the floor plan and fearing that I would find whatever it was making the walking noises made me want to swallow my own tongue.

Little Sis ran ahead of me, giggling into the hallway and disappearing in the back end of the apartment. I still held out hope that maybe it was her, somehow, who was responsible for the walking noises, when I knew it wasn’t possible. I stood for a long time only a few steps deep into the kitchen, which grew darker, and watched as the hallway grew darker still, and then a stooped figure emerged from an unseen room and into the gloom of the hallway. The whole apartment creaked and shook with its each step. It was the shadowy ghost of a man, and he diffused into the hallway, filling it like smoke, and my skin became electric and I think I ran in place like a cartoon character might, sliding my feet back and forth on the linoleum.

An old man emerged into the weak lighting of the kitchen shuffling along with the help of a wooden, swollen-headed shillelagh. He wore a sleeveless T-shirt and tan pants with a black belt knotted tightly around his waist. An asterisk of thin, white hair dotted the top of his head and the same unruly tuft sprouted out from under the collar of his T-shirt. His eyes were big and rheumy, like a bloodhound’s eyes, and he smirked at me, but before he could say anything I screamed and ran through Kelly and out of the apartment.

On the second step I heard him call out (his voice quite friendly and soothing), “Hey, what are all you silly kids up to?” and then I was around a corner, knocking into a wall and clutching onto the handrail, and maybe halfway down when I heard Kelly laughing, and then shouting, “Wait, Paul! Come meet my grandfather. Tour’s over!”

I just about tumbled onto the second-floor landing with everyone else still upstairs calling after me. I was crying almost uncontrollably and I was seething, so angry at Kelly and her sister and myself. I don’t know why I was so angry. Sure, they set me up, but it was harmless, and part of the whole ghost tour/haunted house idea. I know now they weren’t making fun of me, per se, and they weren’t being cruel. But back then, cruel was my default assumption setting. So I was filled with moral indignation and the kind of irrational anger that leads erstwhile good people to make terrible, petty decisions.

I ran back into the second-floor apartment and to Kelly’s bedroom. I took the drawing of her ghost off the bed, tucked it inside my T-shirt, ran back out of the apartment and then down the stairs and out of the house and to my bike, and I pedaled home without ever once looking back. The rest of that summer I didn’t ride my bike by Kelly’s house.

I can’t remember planning what I was going to do with her drawing. I might’ve initially intended to burn it with matches and a can of Mom’s hairspray (I was a bit of a firebug back then . . .) or something similarly stupid and juvenile. But I didn’t burn it or crumple it up. I didn’t even fold it in half. Any creepiness/weirdness attributed to the drawing was swamped by my anger and then my utter embarrassment at my lame response to her grandfather scaring me. I knew that I totally blew it; that Kelly and I could’ve been friends if I’d laughed and stayed and met her grandfather and maybe middle school and high school would’ve gone differently, wouldn’t have been as miserable.

While I on occasion had nightmares of climbing all those steps in the Bishop house by myself, I don’t remember having any nightmares featuring the ghost in the drawing, even though I was (and still am) a card-carrying scaredy-cat. I wasn’t afraid to keep the drawing in my room. I hid it on the bottom of my bureau’s top drawer along with a few of my favorite baseball cards. While I obsessively picked through the play-by-play of that afternoon in Kelly’s house and what she must’ve thought of me after, I never really focused on the drawing and would only ever look at it by accident, when the top drawer was all but empty of socks or underwear and I’d find that toothy grin peering up at me. Then one day toward the end of the summer the drawing was gone. It’s possible I threw it away without remembering I did so (I mean, I don’t remember what happened to the baseball cards I kept in there either). Maybe Mom found it when she was putting away my clean clothes and did something with it, which would explain how it got to be in her box of kid-stuff keepsakes, but Mom taking it and never saying anything to me about taking it seems off. Mom fawned over my grades and artwork. She would’ve made it a point to tell me how good the drawing was. Her taking the picture and putting it on the fridge? Yes, that would’ve happened. But her secreting it away for safekeeping? That wasn’t her.

That summer melted away and seventh grade at Memorial Middle School was hell, as seventh grade is hell for everyone. The students were separated into three teams (Black, White, and Red), with four teachers in each team. The teams never mixed classes, so you might never see a friend in Black team if you were on Red team and vice versa. Kelly wasn’t on my team, and I didn’t even pass her in the hallways at school until after a random lunch in early October. She stood with her back up against a set of lockers by herself, arms folded. It wasn’t her locker, as I didn’t see her there again the rest of the school year. Normally I walked the halls with my head down, a turtle sunk into his protective shell, but before disappearing into my next class, I looked up to find her staring at me. That look is the second of two looks from her that I’ll never forget, though I won’t ever be sure if I was reading or interpreting this look correctly. In her look I saw I can’t believe you did that, and there was a depthless sadness, one that was almost impossible for me to face as it was a direct, honest response to my irrevocable act. Her look said that I’d stolen a piece of her and even if I’d tried to give it back, it would still be gone forever. To my shame I didn’t say anything, didn’t tell her that I was sorry, and I regret not doing so to this day. There was something else in that look too. It was unreadable to me at the time, but now, sitting in my empty house with dread filling me like water in a glass, I think some of that sadness was for me. Some of it was pity and maybe even fear, like she knew what was going to happen to me tomorrow and for the rest of my tomorrows; there wouldn’t necessarily be a singular calamitous event, but a concatenation or summation of small defeats and horrors that would build daily and yearly and eventually overtake me, as it overtakes us all.

I would see her in passing the following year in eighth grade, but she walked by me like I wasn’t there (like most of the other kids did; I’m sorry if that sounds too woe-is-me, but it’s the truth). At the start of ninth grade, she returned to school a totally transformed kid. She dressed in all black, dyed her hair black, and wore eyeliner and Dead Kennedys and Circle Jerks and Suicidal Tendencies T-shirts and combat boots, and hung out with upperclassmen and she was abrasive and combative and smelled like cigarettes and weed. In our suburban town, only a handful of kids were into punk, so to most of us, even us losers who were picked on mercilessly by the jocks and popular kids or, worse, were totally ignored, the punks were scary and to be avoided at all costs. I remember wondering if the Michael Jackson and Duran Duran posters were still hanging in her room, and I wondered if she still had that dream about her ghost and if she still thought that ghost was some part of her. Of course, I later became a punk when I went to college and I now irrationally wonder if punk was another piece of her that I stole and kept for myself.

The summer after ninth grade Kelly and her family sold the house and moved away. I have no memory of where she moved to, or more accurately, I have no memory of being told (and then forgetting) where she moved. I find it difficult to believe that no one in our grade would’ve known what town or state she moved to. I must’ve known where she relocated to at one point, right?

* * *

The baseball game is still on and I’m on the couch with my laptop open and searching for Kelly Bishop on every social-media platform I can think of, and I can’t find her, and I’m desperate to find her, and it’s less about knowing what has become of her (or who she became) but to see if she’s left behind any other parts of herself—even if only digital avatars.

Next to my laptop is her drawing. That it survived all this time and ended up in my possession again somehow now feels like an inevitability.

Here it is:

I remembered it looking like the product of a young artist and being more creepy and affecting because of it. I remembered some of the branches at the top forming the letter K. I remembered the smile and the skin strips and the triangle arms as-is.

I didn’t remember the shadow beneath the hovering figure, and I don’t like looking at that shadow and I wonder why I always peer so intently into those dark spaces. I didn’t remember how its head is turned away from its body and turned to face the viewer, as though the ghost were floating along stage left until we looked at it, until we saw it there. And then it sees us.

I know it’s not supposed to be a doppelgänger, but I remember it looking like Kelly in some ineffable way, and now, thirty-plus years later I think it looks like me, or that it somehow came from me. Even though it’s late and she’s in bed, I want to call Mom and ask her if she looked through the cardboard box one last time before leaving it here (I know she must’ve) and if she saw this drawing and recognized her son from all those years ago in the drawing.

I am glad Catherine and Izzy are not here. I keep saying that I am glad they are not here in my head. I say it aloud too. They would’ve found the drawing before I did, and I don’t know if they would’ve seen me or if they would’ve seen themselves.

My reverie is shattered by a loud thud upstairs, like something heavy falling to the floor.

There is applause and excited commentators chattering on my television, but I am still home alone and there is a loud thud upstairs.

Its volume and the suddenness of its presence twitches my body, but then I’m careful to stand up slowly and purposefully from the couch. Worse than the incongruity of noise coming from a presumably vacant space is the emptiness the sound leaves behind, a void that must and will be filled.

I again think of driving to the Cape or just driving, somewhere, anywhere. I shut the television off and I anticipate the sound of footsteps running out of the silence toward me, or a rush of air and those triangle arms reaching more and the shadow on the floor behind it.

Everything in me is shaking. I call out in a voice that no one is there to hear. I threaten calling 911. I tell the empty or not-empty house to leave me alone. I try to be rational and envision the noise being made by one of the shampoo bottles sliding off the slippery ledge in our shower but instead I can only see the figure in my drawing, huddled upstairs, waiting. And it is now my drawing, even if it’s not.

The ceiling above my head creaks ever so slightly. A settling of the wood. A response to subtle pressure.

I imagine going upstairs and finding a menagerie of Kelly’s ghosts waiting for me: there is Greg with two g’s tearing apart the hapless Rolph, and the desperately lonely Mrs. Black sitting in a chair patiently waiting, and the feckless shut-in Darcy Dearborn. Or will I find the ghost of a part of me that I never let go: a lost and outcast adult I always feared people (myself included) thought I’d become?

Is that another creak in the ceiling I heard?

I listen harder, and maybe if I listen long enough I’ll hear a scream or a growl or my own voice, and it is as though the last thirty years of my life have passed like the blink of summer, and everything that has happened in between doesn’t matter. Memories and events and all the people in my life have been squeezed out, leaving only room for this distilled me on this narrowing staircase, and right now even Catherine and Izzy feel like made-up ghost stories. There is only that afternoon in Kelly’s place and now the impossibly older me alone in a house that’s become as strange, frightening, and unknowable as my future.

As I slowly walk out of the TV room and up the stairs toward the suddenly-alive-with-sound second floor, I don’t know what I’m more afraid of: seeing the ghost I stole grinning in the dark or seeing myself.

For Emma Tremblay and Ellen Datlow

MEAN TIME

The old man’s name began with an r, I think, yeah, but definitely a capital R. Mom told me to stay away from R. Dad said R was harmless but I shouldn’t encourage him. Sherry, the semi-goth teen who lived on the floor below us and spent her afternoons listening to the Smiths and Kelly Clarkson told me R spent too much time in his pockets and that he smelled like what she imagined a burning jellyfish would smell like. Sherry was wrong. R smelled like chalk. He had countless chalk sticks in his pockets and dust was all over his hands and his brown wool suit. The smears looked like letters tattooed on his lapels and sleeves. R used his chalk to draw lines on the sidewalks and streets. Or arcs, not lines. Arcs would be a more accurate description. Whatever. R walked backward, all hunched over, tip of chalk pressed against the cement or brick or cobblestone, and he drew until the stick disintegrated into dust. R drew his looping arcs and lines from Gracey’s Market to Wilhelmina’s Flower Festival then to Frank and Beans Diner and on and on, to points A, then B, and to C, then to D, past the alphabet and to points we’d have to name with alphas and epsilons. The first time I worked up the courage to ask him the obvious, he gave me an obvious answer. R used the chalk to find his way home because even in our small city he was afraid he would get lost. We all lived in a city that was smaller than most towns, so I’d heard. All our apartment buildings, libraries, markets, salons, and restaurants were crammed together, like space was something to be shared intimately with everyone. So, that first day, after I asked him what was what, after he told me what was what, we shared our space quietly, uncomfortably, then, he said, “Well, okay, little one, in the mean time, I have more errands to do.” Back then I didn’t know “meantime” was one word, so I imagined it as two. Later, I tried following him in the afternoon, as he backtracked over his loops and lines, reliving his previous paths, but he walked too fast for me, and I lost him and the chalk path in the maze of alleys between Gorgeous George’s Peach Pit and Dolly Lamas Liquor Mart. I tried restarting on the path, but I couldn’t follow the intersecting arcs he’d drawn earlier, and never found the beginning or the end. The chalk lines faded overnight, washed away by light rain, according to Mom. Dad liked to try to scare me and told me the night scrubbed it all away. Sherry said the students who dropped out of trade school cleaned the streets and sidewalks at night. Didn’t matter where the lines went because R was always back out there the next morning and for all the