Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

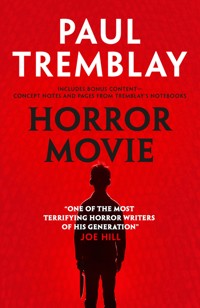

"Slasher movies are seen by some as kitschy fun, but this is a seriously disturbing novel, delving into the sacrifices art demands, psychological trauma and how monsters are made. Sometimes painful reading, it's also incredibly gripping, smart and scary." The Guardian The New York Times bestseller! Includes bonus content - see concept notes and pages from Tremblay's notebooks. The monster at the heart of a cult 90s cursed horror film tells his shocking and bloody secret history. Slow burn terror meets high-stakes showdowns, from the bestselling author of A Head Full of Ghosts and The Cabin at the End of the World. Summer, 1993 – a group of young guerrilla filmmakers spend four weeks making Horror Movie, a notorious, disturbing, art-house horror film. The weird part? Only three of the film's scenes were ever released to the public. Steeped in mystery and tragedy, the film has taken on a mythic renown. Decades later, a big budget reboot is in the works, and Hollywood turns to the only surviving cast member – the man who played 'the Thin Kid', the masked teen at the centre of it all. He remembers all too well the secrets buried within the original screenplay, the bizarre events of the filming, and the crossed lines on set. Caught in a nightmare of masks and appearances, facile Hollywood personalities and fan conventions, the Thin Kid spins a tale of past and present, scripts and reality, and what the camera lets us see. But at what cost do we revisit our demons? After all these years, the monster the world never saw will finally be heard.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1 Now: The Producer

2 Then: The First Day

3 Then: The Pitch Part 1

4 Then: The Pitch Part 2

5 Now: The Director Part 1

6 Then: The Hotel

7 Then: Classroom Scene

8 Then: The Sleepover

9 Now: Feral Fx Part 1

10 Then: The Cigarette

11 Then: The Convention Part 1

12 Then: The Hospital

13 Now: The Director Part 2

14 Then: Valentina’s House Part 1

15 Now: The Director Part 3

16 Then: The Convention Part 2

17 Now: Feral Fx Part 2

18 Then: Valentina’s House Part 2

19 Then: The End

20 Now: The End

Acknowledgments

Horror Movie Notebook

About the Author

“Paul Tremblay is one of the most terrifying horror writers of his generation and his new chiller, Horror Movie, is a reason for excitement.”

JOE HILL, #1 New York Times bestselling author

“In the hands of Paul Tremblay the story of a lost movie becomes a reflection on fear, the monsters we all are and an investigation on what is a horror novel. It’s bold, fearless, a bit sad and very, very scary.”

MARIANA ENRIQUEZ, author of Our Share of Night and Things We Lost in the Fire

“Horror Movie delves into the dark shadows of cursed movie lore and delivers the scary goods all whilst bringing something new to the table to keep you guessing right until the bitter end.”

NEIL MARSHALL, director of Dog Soldiers and The Descent

“An account of working in the horror film industry that lulls you into a sense of normalcy, only to embroil you in a piece of metafiction so unsettling that it creeps out of the book and into your consciousness. The sinister tone is so hypnotising that it feels like a shared nightmare half remembered from somewhere or other... The cursed notion that horror lore can be self fulfilling had me scared to finish the book.”

ALICE LOWE, actress and director of Prevenge

“Complex and insightful. Eminently readable and intelligent. Above all, disturbing... Paul Tremblay has artfully crafted a dual narrative, and an absorbing story of creativity becoming mania, and the ugliness (and danger) of morbid self-obsession ... I left the story wondering if our secret, damaged identities should remain masked, secreted under a bed and left in the dark. Above all, you should remain in your seat until the end credits of Tremblay’s Horror Movie.”

ADAM NEVILL, author of The Ritual and No One Gets Out Alive

“Horror Movie is a gift of a novel, combining creeping dread and slippery narrative twists with a palpable love for the genre. Paul Tremblay is unmatched in creating horror that feels at once outsized and disturbingly personal. God I loved this book!”

JULIA ARMFIELD, author of Our Wives Under the Sea and Private Rites

“A work penned by Paul Tremblay is always such an extraordinary gift. Probing, insightful, deceptively tender until it’s not—until bodies are inevitably twisted, mangled and the blood begins to flow. His brand of horror is compassionate, nuanced, deeply intimate, and yet also spectacularly brutal. I dare you to turn the final page of any of his novels and claim that you are unchanged. To read a book by Tremblay is to partake in a sacred communion of the soul—to endure the terror and, more importantly, to learn about yourself.”

ERIC LAROCCA, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

“Tremblay’s best work, now one of my favorite horror novels, period. Daring and original ... painful and emotional and filled with inexorable dread. The construction is masterful. This one is going to stay with me the way very few novels ever do.”

CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN, author of All Hallows and Road of Bones

“Sometimes things are lost for a reason, but Tremblay reminds us of our innate, irresistible urge to look even when we’re likely to be turned into a pillar of salt. A meditation on horror, personal demons and how easily they erupt into everyday life, Horror Movie is a Pandora’s box of a book.”

ANGELA “A.G.” SLATTER, award-winning author of The Briar Book of the Dead

“Another brilliant manipulation of our fears from the reigning master of dread. Horror Movie shows there’s a monster lurking inside every one of us.”

ALMA KATSU, author of The Fervor

“Horror Movie is not only a haunting, unsettling, and utterly absorbing novel—it is also a twisted manifesto for art and the parts of ourselves we shed in order to create it. It messed with my head and I loved every minute of it.”

CLÉMENCE MICHALLON, internationally bestselling author of The Quiet Tenant

“Macabrely funny and incredibly smart, Horror Movie cements Tremblay’s place as a master of horror. It encapsulates the unease of right now—a runaway culture of self-reference with bloody hands. It’s everything a horror novel ought to be: lean, mean, and genuinely scary.”

SARAH LANGAN, author of Good Neighbors and A Better World

“A profound, heart-wrenching, terrifyingly honest novel that’s also a cinematic page-turner. Horror Movie zooms in on creation and consumption, integrity and ego, admiration and obsession, and how the desperate search for connection through art can be beautiful, or disastrous. This book is a gift and a curse.”

RACHEL HARRISON, nationally bestselling author of Black Sheep

“You may think you see some of the wheels turning inside Tremblay’s bleak story about art, atrocities, and the callousness of teens, but as with A Head Full of Ghosts, you’re only scratching the surface of his dark vision. The Thin Kid will haunt you.”

ALLY WILKES, author of All the White Spaces

“Paul Tremblay proves, yet again, that he is one of the brightest stars at work in horror today. Don’t watch this feature alone. Bring someone to hold hands with in the dark.”

PRIYA SHARMA, auhor of All the Fabulous Beasts

“A steadily escalating exercise in dread, shot through with moments of unexpected pathos ... With each new book, Paul Tremblay has continued to grow and challenge himself as a writer, in the process building one of the most substantial bodies of work of his generation. Horror Movie is a literary high-wire act, performed with aplomb high above the breathless crowd.”

JOHN LANGAN, author of The Fisherman and Corpsemouth and Other Autobiographies

“Paul Tremblay has made the ‘Mandela Effect’ come to life. His writing is so convincing he’s going to make people think they really saw Horror Movie and it’s going to disturb everyone for decades after they read this book. A triumph.”

JOHNNY MAINS

“A brilliant piece about the masks we know about and the masks we don’t, the ones we’re forced to wear for a lifetime because of our depression and the things we create to make sense of terrible things. He captures the fugue of being young, of finding a bridge to immortality when you’re invulnerable, of making mistakes you can't take back. It is intimately heartbreaking and beautifully written, and it’s scary in a way that attaches itself to your shame and self-loathing and just starts eating away. It’s extraordinary.”

WALTER CHAW, author of A Walter Hill Film

HORRORMOVIE

ALSO BY PAUL TREMBLAYAND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Disappearance at Devil’s Rock

A Head Full of Ghosts

The Cabin at the End of the World

Growing Things and Other Stories

Survivor Song

The Little Sleep and No Sleep Till Wonderland Omnibus

The Pallbearers Club

The Beast You Are: Stories

PAULTREMBLAY

HORRORMOVIE

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Horror Movie

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781803364292

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835412688

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364308

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Paul Tremblay 2024

Greateful acknowledgement is made to Pile for permission to reprint an excerpt from "Away in a Rainbow!" (written by Rick Maguire), courtesy of Pile © 2010

Andrei Tarkovsky quote from "Andrei Tarkovsky’s Advice to Young Filmmakers: Sacrifice Yourself for Cinema," by Colin Marshall, openculture.com

Paul Tremblay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

FOR LISA, COLE, AND EMMA

In Memoriam, Peter Straub

They should be prepared for the thought that cinema is a very difficult and serious art. It requires sacrificing of yourself. You should belong to it. It shouldn’t belong to you.

—ANDREI TARKOVSKY

Mr. was bornin a cocoon.He’ll come out better.He’ll come out soon.Or let’s hope.

—PILE, “AWAY IN A RAINBOW!”

NOW:

THE PRODUCER

1

Our little movie that couldn’t had a crew size that has become fluid in the retelling, magically growing in the years since Valentina uploaded the screenplay and three photo stills to various online message boards and three brief scenes to YouTube in 2008. Now that I live in Los Angeles (temporarily; please, I’m not a real monster) I can’t tell you how many people tell me they know someone or are friends of a friend of a friend who was on-set. Our set.

Like now. I’m having coffee with one of the producers of the Horror Movie remake. Or is it a reboot? I’m not sure of the correct term for what it is they will be doing. Is it a remake if the original film, shot more than thirty years ago, was never screened? “Reboot” is probably the proper term but not with how it’s applied around Hollywood.

Producer Guy’s name is George. Maybe. I’m pretending to forget his name in retribution for our first meeting six months ago, which was over Zoom. While I was holed up in my small, stuffy apartment, he was outdoors, traipsing around a green space. He apologized for the sunglasses and his bouncing, sun-dappled phone image in that I-can-do-whatever-I-want way and explained he just had to get outside, get his steps in, because he’d been stuck in his office all morning and he would be there all afternoon. Translation: I deign to speak to you, however you’re not important enough to interrupt a planned walk. A total power play. I was tempted to hang up on him or pretend my computer screen froze, but I didn’t. Yeah, I’m talking tougher than I am. I couldn’t afford (in all applications of that word) to throw away any chance, as slim as it might be, to get the movie made. Within the winding course of our one-way discussion in which I was nothing but flotsam in the current of his river, he said he’d been looking for horror projects, as “horror is hot,” but because everything happening in the real world was so grim, he and the studios wanted horror that was “uplifting and upbeat.” His own raging waters were too loud for him to hear my derisive snort-laugh or see my eye-roll. I didn’t think anything would ever come from that chat.

In the past five years I’ve had countless calls with studio executives and sycophantic producers who claimed to be serious about rebooting Horror Movie and wanting me on board in a variety of non-decision-making, low-pay capacities, which equated to their hoping I wouldn’t shit on them or their overtures publicly, as I and my character inexplicably have a small but vociferous, or voracious, fan base. After being subjected to their performative enthusiasm, elevator pitches (Same movie but a horror-comedy! Same movie but with twentysomethings living in L.A. or San Francisco or Atlanta! Same movie but with an alien! Same movie but with time travel! Same movie but with hope!), and promises to work together, I’d never hear from them again.

But I did hear back from this producer guy. I asked my friend Sarah, an impossibly smart (unlike me) East Coast transplant (like me) screenwriter, what she knew about him and his company. She said he had shit taste, but he got movies made. Two for two.

Today, Producer-Guy George and I are in Culver City comparing the size of our grandes while sitting at an outdoor metal wicker table, the table wobbly because of an uneven leg, which I anchor in place with the toe of one sneakered foot. Now that we’re in person, face-to-face, we are on more equal ground, if there is such a thing as equality. He’s tan, wide-chested, wearing aviator sunglasses, a polo shirt, and comfortable shoes, and younger than I am by more than a decade. I’m dressed in my usual uniform; faded black jeans, a white T-shirt, and a world weariness that is both affect and age-earned.

He talks about the movie in character arcs and other empty buzzword story terms he gleaned from online listicles. Then we discuss what my role might be offscreen, my upcoming meeting with the director, and other stuff that could’ve been handled in email or a phone/Zoom call, but I had insisted on the in-person. Not sure why beyond the free coffee and to have something to do while I wait for preproduction to start. Maybe I wanted to show George my teeth.

As we’re about to part ways, he says, “Hey, get this, I randomly found out that a friend of my cousin—a close cousin; we’d spent two weeks of every summer on Lake Winnipesaukee together from ages eight to eighteen—anyway, this friend of hers worked on Horror Movie with you. Isn’t that wild?”

The absurd part is that I’m supposed to go along with his (and everyone else’s) faked connection to and remembrance of a movie that has become fabled, become not real, when it was at one time decidedly, quantitatively real, and then the kicker is there’s the social expectation that I will acknowledge our new shared bond. I get it. It’s all make-believe, the business of make-believe, and it bleeds into the unreality of the entertainment ecosystem. Maybe it should be that way. Who am I to say otherwise? But I refuse to play along. That’s my power play.

I ask, “Oh yeah, what’s their name?”

I insist people cough up the name of whoever was supposedly on-set with me thirty years ago. I respect the person who at least gives one, putting their cards on the table so I can call their bluff. Unerringly, Industry Person X (now, there’s a real monster; watch out, it’s Industry Person X, yargh blorgh!!!) gets rattled and is affronted that I dare ask for a name they cannot produce.

The umbrella over our heads offers faulty, imperfect shade. Producer-Guy George’s tan is suddenly less tan. He asks, “My cousin’s name?”

“No.” I’m patient. After all, with my ceremonial associate-producer title, he and I are going to be coworkers. “The name of your cousin’s friend. The one who was on-set with me.”

“Oh, ha, right. You know, she didn’t tell me, and I forgot to ask.” He waves his hands in the air, a forget-I-said-anything gesture. “Her friend was probably a grip or an extra and you wouldn’t remember.”

I lean across the tabletop, lifting my foot away from the leg’s clawed foot. The table quakes. George’s empty coffee cup jumps, then falls onto its side, and circles an imaginary drain, leaking drops of tepid brown liquid. He fumbles for the cup comically, but he’s too ham-fisted for real comedy, which must always include pathos. He rights the cup, then leans in, sucked into the gravitational pull of my terrible smile, a smile that never made it on-camera once upon a time.

I say, “Your cousin didn’t know anyone who was there, and let’s not pretend otherwise.”

He blinks behind his sunglasses. Even though I can’t see his eyes I know that look. My power play is a form of mesmerism: calling out the liars as liars without having to use the word.

I break the spell by asking him if I can borrow ten bucks for parking because I don’t have any cash on me, which may or may not be true. How to win friends and influence people, right?

Listen, I’m a nice person. I am. I’m honest, polite, giving when I can be, commiserative, and I’ll give you the white T-shirt off my back if you need it. I can even tolerate being buried in bullshit; it comes with my fucked-up gig. But people lying about being on Horror Movie’s set gets to me. I’m sorry, but if you weren’t there, you didn’t earn the right to say you were. It’s less narcissism on my part (though I can’t guarantee there’s not a piece of that in there; does a narcissist know if they are one?), and more my protecting the honor of everyone else’s experience. Since I can’t change anything that happened, it’s all I can do.

Our movie did not feature a crew of hundreds, never mind tens, as in multiple tens. There weren’t many of us then, and, yeah, there are a lot fewer of us still around now.

THEN:

THE FIRST DAY

2

The first day of filming was June 9, 1993. I don’t remember dates, generally, but I remember that one. Our director, Valentina Rojas, gathered cast and crew. Except for Dan Carroll, our director of photography and cameraman, who was somewhere in the yawning desert of his thirties, the rest of us were stupid young; early or mid-twenties. I mean “stupid” in the best and most envious ways now that I am over fifty. Valentina waited like a teacher for everyone to quiet down and settle into a half circle around her. After a bit of silence and some nervous giggles, Valentina gave a speech.

Valentina liked speeches. She was good at them. She showed off how smart she was, and you were left hoping some of her smartness rubbed off on you. I enjoyed the rhythm and lilt of her Rhode Island accent that slipped out, maybe purposefully. If she sounded full of herself, well, she was. Aggressively, unapologetically so. I admired the ethos—it was okay to be an egomaniac or an asshole or both if you were competent and weren’t a fucking sellout. Back then, nothing was worse than a sellout in our book. Compromise was the enemy of integrity and art. She and I kept a running list of musical acts who rated as sellouts, eschewing the obvious U2, Metallica, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, which were givens, for subtler, more nuanced choices, and she’d include our local UMass– Amherst heroes, the Pixies, on her list just to piss off anyone eavesdropping on us.

I mention this now, in the beginning, as our passing collegiate friendship (I’m too superstitious or self-conscious, I can’t remember which, to rate it as a full-fledged relationship) was why I was cast as the “Thin Kid.” That and my obvious physical attributes, and a thirst for blood.

I know, the blood crack is a fucking awful joke. If that joke bothers you, I get it. Don’t you worry, I hate me too. But listen, if I’m going to tell any of this, I must do it my way, otherwise I’d never get out of bed in the morning. No compromise.

With our small army gathered on the shoulder of a wide suburban dead-end road, Valentina reiterated the plan was to shoot the scenes in the film’s chronological order, each scene building off the prior one until we made it to the inevitable end. Valentina said we had four weeks to get it all done, when she really meant five. No one corrected her.

I hung out in the back of the circle, vibrating with nervousness and a general sense of doom. Dan whispered to me, not unkindly, that Valentina’s mom and dad wouldn’t pay for week five. Dan was a short, wiry Black man, exacting but patient with us film newbies and nobodies. He co-owned the small but well-regarded production company that shot and produced commercials as well as the long-running Sunday-morning news magazine for the Providence ABC affiliate. I smiled and nodded at his joke, like I knew anything about the budget.

Valentina ended her spiel with “A movie is a collection of beautiful lies that somehow add up to being the truth, or a truth. In this case an ugly one. But the first spoken line in any movie is not a lie and is always the truest.”

Valentina then asked Cleo if she had anything to add. Cleo stood with an armful of mini scripts for the scenes being shot that day. In filmmaking lingo, these mini scripts are referred to as “sides.” Mine was folded in the back pocket of my jeans. The night before had been my first opportunity to read the day’s scenes.

Cleo had long red hair and fair skin. She was already in wardrobe and looked like the high schooler she would be playing, preparing to make a presentation in front of the class. Cleo couldn’t look at anyone and spoke with her eyes pointed toward the pavement under our feet.

She said, “This movie is going to be a hard thing to do. Thank you for trusting us. Let’s be good to each other, okay?”

HORROR MOVIE

Written by

Cleo Picane

EXT. SUBURBAN SIDE STREET – AFTERNOON

The street is a tunnel. Its walls are two-story homes on wooded lots. The interwoven, incestuous tree branches and green leaves hoard the sunlight and form the tunnel’s ceiling.

That the houses are well kept and front lawns and shrubs groomed are the only visible signs of human occupancy. This suburban neighborhood is a ghost town -- no, it’s a picturesque hell so many desperately strive for, and so few will escape.

Four late-high-school-aged TEENS walk down the middle of the road, one that sees little traffic. There are no yellow lines, no demarcated lanes, which offers the illusion of freedom.

VALENTINA (she’s short, thick curly black hair spills out from under a knit beanie, eyeliner rings her downturned eyes, she walks heavily in chunky boots, wears black and gray baggy clothes, the baggiest of baggy clothes, her high school survival camouflage, she imagines the clothes make her if not invisible then ignorable to classmates).

CLEO (dresses like the rest of her classmates, which is a more effective high-school-survival camouflage than Valentina’s, she has long red hair pushed off her forehead with a headband, wide-lensed glasses, jeans pegged at the ankles above her white high-top Chuck Taylors, a firetruck-red blazer over a horizontal black-and-white-striped top, Cleo does well in school and struggles with depression and she only leaves her bedroom for school or to hang out with her three friends). Cleo carries a crinkled grocery PAPER BAG.

KARSON (average build and height, slumped shoulders that might one day be broad, he wears overalls because he thinks they make him look taller, overall straps are clipped over a charcoal-gray sweatshirt ripped and frayed around the collar, his dark-brown hair is long in the front and his head is shaved on the sides and back, he has a nervous tic of running his hands through his bangs).

Valentina, Cleo, and Karson walk in a line, a breezy, step-for-step choreography. When no one else is around to see and judge them, they are rock stars.

The three teens don’t talk, but they take turns knocking into the person next to them, then passing the hip-bump along while laughing and never breaking the formation. They are, in this moment, unbreakable. Their friendship is beyond language. Their friendship is a perpetual-motion engine. Their friendship is easy and gravid and intense and paranoid and jealous and needy and salvatory.

A fourth teen, the THIN KID, lags, languishes behind their line. He blurs in and out of our vision like a floaty in our eyes.

We do not, cannot, and will not clearly see the Thin Kid’s face.

But we almost see him, and later, we will have a false memory of having seen his face.

That face will be built by what isn’t seen, built from an amalgam of other faces, faces of people we know and people we’ve seen on television and movies and within crowds. Perhaps we’ll imagine a kind face when it is more likely he has a face, to our enduring shame, that does not inspire our kindness.

There will be glimpses of the Thin Kid’s jeans, the color too dark, too blue, and his long feet sheathed in sneakers that are cheap, generic, not cool within any subculture.

There will be a clear shot of his pale matchstick arms, slacken ropes spooling out from the billowing sail of a white T-shirt, logo-less, as though he hasn’t earned the right to wear a brand.

There will be a blur of shaggy brown hair and his rangy profile in an out-of-focus blink.

The Thin Kid walks behind the three teens, out of step, out of time, working harder than they do, and he’s walking faster than they are, but he will not overtake them, nor will he catch them.

Cleo looks over her shoulder, once, at the Thin Kid.

Her easy smile fades, and she clutches the paper bag more tightly.

EXT. DEAD-END STREET/FOREST LINE – MOMENTS LATER

The teens stop walking at the end of the dead-end street, at the mouth of an overgrown path into the WOODS.

A pair of TRAFFIC CONES and a rickety WOODEN HORSE block the entrance.

KARSON

(eyes only for the path)

Are you sure this is the

right way?

VALENTINA

(pushes sleeves overher angry hands)

You’re the one who said you

used to ride your bike there

and did laps around it until

you popped a tire.

KARSON

(stammers)

Well, yeah, but that was a long

time ago, and I’m pretty sure

I got there a different way.

Valentina curls around the cones and horse and onto the path. Her sleeves accordion back over her hands.

VALENTINA

This is the way we’re going.

Karson shrugs, runs his hands through his hair, follows.

Cleo is next onto the path.

She pauses, reaches across the barrier, reaches for the Thin Kid’s hand.

We see him from behind. We do not see his face. We do not see his expression. We cannot know what he is thinking, but maybe we can guess.

The Thin Kid stuffs his hands into his pockets petulantly, or playfully.

CLEO

(whispers, neither patient nor impatient)

Come on. Let’s go. Trust your friends.

The Thin Kid does as she says and steps onto the path.

EXT. FOREST PATH – MOMENTS LATER

The path is overgrown and narrow. They walk single file. They lift wayward branches or crouch under them.

KARSON

What if there are other kids there?

VALENTINA

There won’t be.

KARSON

How do you know? You don’t know.

Valentina hooks an arm through Karson’s arm. With her sleeve-covered hand, she pats the crook of his elbow.

She’s being both condescending and a good friend, acknowledging and downplaying his well-founded fears of “other kids.”

VALENTINA

Hey. We’ll be all right.

Cleo holds up and shakes the paper bag, like it’s a town crier’s bell, like it’s a warning.

CLEO

(uses an exaggerated deep voice, her father’s voice)

We’ll just scare those punks away, and give them what-for.

Valentina laughs.

Karson shakes his head and mumbles to himself, and when Valentina detangles away from their linked arms, he squeezes the top of her beanie hat, makes a HONK sound, then grabs and pulls the end of her sleeve, stretching it out like taffy.

Valentina mock screams, spins, and slaps him across the chest with the extra cloth.

THIN KID

Why am I--

VALENTINA

(interrupts)

There’s no “why.” I’m sorry, there never is.

This is important: she isn’t mocking the Thin Kid, and she doesn’t sound mean or aloof. Quite the opposite. Valentina sounds pained, sounds as sad as the truth she uttered.

She cares about the Thin Kid.

Cleo and Karson care too. They care too much.

The Thin Kid plucks LEAVES from the branches they pass and puts them in his pockets.

THEN:

THE PITCH PART 1

3

In mid-April of 1993 Valentina left a message on my apartment’s answering machine. We hadn’t talked for almost two years. She got the phone number from my mother, who was awful free with those digits, if you ask me. Valentina said she had a proposition, laughed, apologized for laughing, and then she assured me the proposition was serious. How could I resist?

She and I didn’t go to college together, but we’d met as undergrads. I bused tables and worked at Hugo’s in Northampton, a bar that was close enough to campus that my shitbox car could survive the drive and far enough away that I wouldn’t have to deal with every knucklehead who went to my school. One weeknight when the bar wasn’t packed, I was stationed by the door and pretended to read a dog-eared copy of Naked Lunch (cut me some slack, Hugo’s was that kind of place in that kind of town), and Valentina showed up with two friends. Her dark, curly hair hung over her eyes. She wore a too-big flannel shirt, the sleeves hiding her hands until she wanted to make a point, then she pointed and waved those hands around like they were on fire. She was short, even in her thick-heeled combat boots, but she had physical presence, gravitas; you knew when she entered or left the room. I checked her ID and made a clever quip about the whimsy of her exaggerated height on her government-issued identification card. She retaliated by snatching my book and chucking it into the street, which was fair. Later, she and I ended up playing pool, awkwardly made out in a dark corner, and exchanged phone numbers. We hung out a few times after that, but more often we’d run into each other as regulars at Hugo’s. I was happy to be the weird guy (“Weird Guy” was what she called me) from the state school who occasionally entered her orbit. My comet-like appearances made me seem more interesting than I was. I graduated from the University of Massachusetts–Amherst with a communications degree and student loans that I would default on twice. She graduated from Amherst College—much more prestigious and expensive than Zoo Mass. Postgraduation, I’d figured our paths would never cross again.

When I returned Valentina’s call, our chat was brief. She wouldn’t tell me what the proposition was over the phone, so I agreed to meet her and her friend Cleo at a restaurant on Bridge Street in Providence that weekend. My car (the same beater I’d had in college) barely made the trip down from Quincy, Massachusetts. It had a standard transmission and when on the highway I’d have to hold the gear shift in fifth or it would pop out into neutral. On the ride back, I gave up and drove 70 in fourth gear. I miss that loyal little car.

A restaurant called the Fish Company overlooked the inky Providence River. Too late for lunch, too early for dinner, the place was more than half-empty on a cloudy but warm Sunday midafternoon. I was fifteen minutes late, but I had no problem finding Valentina and Cleo sitting outside, on the wooden dock patio, away from prying ears. They had an open binder on their table, pages filled with rough sketches boxed within long rectangles. I would learn later that Valentina had storyboarded the entire movie, shot by shot. Next to Cleo a paper grocery bag occupied an empty chair. Upon my approach, Cleo slid the chair closer to her, communicating that I wasn’t to displace the bag. Valentina closed the binder and stashed it in an army-surplus backpack.

She greeted me with “What’s up, Weird Guy?”

Aside from the beanie atop her curly hair, Valentina’s appearance hadn’t changed much at first blush. After a minute of catch-up chatter, it was clear she’d become an adult, or more adult than me, anyway. The twitchy glances, look-aways, and the we-don’t-know-who-we-are-yet-but-I-hope-other-people-like-me half smiles we were all made of in college had hardened and sharpened into confidence of purpose but not yet disappointment. Maybe it was a mask. We all wear them. I got nervous because it appeared that whatever their proposition was must be a serious one. I wasn’t prepared for serious.

Cleo was Valentina’s friend from high school. She had long, red hair, big glasses, and a boisterous, infectious, at-the-edge-of-control laugh. When she wasn’t laughing, there was a blank intensity to her gaze and the memory of her irrepressible laughter seemed an impossible one. Maybe I’m projecting now, all these years later, but she was the kind of person who wore sadness and a type of vulnerability that did not translate into her being a pushover. Far from it. She’d battled and battled hard. But if she wasn’t broken yet, she would be, as the world breaks us all.

While we waited for our food Valentina explained that she and Cleo were making a movie; Valentina as director, Cleo as screenwriter, and both would be acting in the film as well. They had funding from a variety of local investors in addition to a modest grant from Rhode Island. It wasn’t a lot of money, but they would make it work. They planned to begin production in a few months. They had a tight shooting window because one of their locations, an old, condemned school building, was going to be demolished in midsummer.

I was gobsmacked despite knowing Valentina had completed a film-studies minor as an undergraduate. I don’t remember what her major was, but it was a course of study her parents had insisted upon so that she would be, in their eyes, employable. Her mother was a marketing director, and her father owned a local chain of combo car wash/gas stations. Because her parents were footing the entirety of the hefty tuition bill, they had insisted on having a say in what they called their “educational investment.” Valentina was an only child, and when she talked about her parents, even in passing, it was with a crackling, bipolar mix of pride and seething resentment. Regardless of the major in which she’d earned her degree, film was her passion. When we were students, I was more obsessed with indie/underground music than film, though I’d spent enough hours as a lonely, brooding teen watching and rewatching movies on cable TV that I could hold on to the threads of her deeper film discourse by my fingertips. She and I had once attended a screening of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and later at Hugo’s she explained expressionism with the aid of scratchy sketches on bar napkins: the strange, moody, angularly distorted set design represented the interior reality of the story. I remember talking out of my ass, attempting to be smarter than I was by drawing parallels to the performative aspect of punk and art-rock bands from the ’70s and ’80s. To Valentina’s credit, she didn’t tell me I was full of shit and helped connect some of those musical dots with me. It was one of those absurd and perfect bar conversations that young, new friends have, portentously vibrating with perceived and real discovery. I can’t decide if I’m now incapable of such a discussion because I know too much or because life has proven that none of us knows anything.

In response to their making-a-movie reveal, I said, “Wow” and “Sounds amazing” at least a dozen times because I didn’t know what else to say until I worked up the courage to ask the obvious. “So why am I here?”

Valentina said, “Good question. Why is he here, Cleo?” She flailed her arms in the air, overdramatic, hammy. “Are we going to ask him?”

Cleo didn’t smile or laugh at what I thought was a joke. That stare of hers. I can still feel it, crawling over, then under, my skin to knock on my bones; the look of a chess master surveying the board and all the possible moves and outcomes, and knowing no matter what she did, she was going to draw or lose.

She said, “Yeah, I guess we should.”

“Great.” Valentina clapped her hands together once. “So, we want you for one of the roles. One of the most important ones.”

After asking them both multiple times if they were fucking with me, they assured me they were not. I told them I’d never acted before, not even in elementary school, which was mostly true, which means it was a lie. I’d taken a drama class my college sophomore year, and our final exam was a group-written and -performed sketch, neither aspect of which is worth detailing here. Suffice it to say, I did not take any more drama classes.

Valentina said, “That’s not a problem. We’ll get the performance we need out of you.”

“That sounds like a threat.” I laughed. They did not.

My legs twitched, eyes blinked, heart rate spiked, and I had to fight the urge to run. Instead, I curled into myself, picked at my beer-bottle label, which sloughed off in slashed, wet clumps. I said, “Oh, man, I don’t know. You don’t want my ugly mug on a screen.” At this, Valentina rolled her eyes and waved a dismissive hand at my desperate self-deprecation. “And I’d be so nervous about memorizing lines and fumbling through them or sounding like a robot, unless you want me to play a robot, like the Terminator or something, but I’d have to be the fucked-up, failed prototype. The one Skynet wouldn’t send out into the field, and maybe some human or mutant finds me in the trash, turns me on, and all I do is ask them if anyone wants to get a pizza or something. See, I’m already rambling. Is this my audition?”

Cleo laughed. “In a weird way, you’re not that far off.”

“That’s Weird Guy for you,” Valentina said. “Relax. It is a big role but it’s a nonspeaking role. You’ll be on-camera a lot, but you won’t have any lines.”

Even though there was no way I was doing this, I was disappointed that my role would have no lines. I felt it to be a judgment on my character.

Cleo said, “Well, he has one, maybe two lines in the beginning.”

Valentina waved her hands again. “We could even have those read by someone else in post, if you’re a complete disaster, but you won’t be.”

Cleo adjusted her glasses. She looked at me like something terrible was going to happen in my near future. Now I get that look a lot, or maybe I more easily recognize it. But then I’d never felt so watched, so observed, and her scrutiny was a horror initially. By the end of our meeting and meal, having that unvarnished attention paid to me when I’d been so used to hiding, even if it felt uncomfortable and intrusive, was intoxicating. That feeling was why I said yes without saying it. It felt like a chance to create another version of myself, one over which I’d have more control. Which, of course, was ludicrous and wildly wrong. I’d be changed, but would it be by my own hands? Fuck me, I sound like a pretentious actor.

There was something, many somethings, they weren’t telling me. I blurted out, “Okay, so why me?”

“We need someone who is your size,” Cleo said.

“Oh. So, I really am going to be a robot and I fit the suit?” I sat up straight and robot-chopped my arms up and down. “I hope it’s not too heavy or too hot. I wore a full-body pizza slice costume once at a PawSox game. I smelled like a muppet with BO for a full day after.”

“You’re not playing a robot,” Valentina said. “We need someone who is your height and build.”

“My height and build?” My face flashed an instant embarrassed red. I noticed Cleo’s face mirrored mine. I tried to joke, but I know I sounded hurt. “You mean, my lack of build? It takes a lot of work to maintain this physique.” I flexed a nonexistent bicep.

Valentina said, “Oh stop, you look great. It’s just the role requires a male who is tall and . . . lanky. Looks like he could still be in high school. And I mean the movie version of high school, which always shades a little older. Not as old as the teens in De Palma’s Carrie. Fuck, some of those actors had crow’s feet wrinkles when they smiled. And Cleo and I will be returning to the hell of high school with you. It’ll be fun.”

“Yeah, sounds so fun.”

Cleo said, “Your name in the script is the Thin Kid.” She smiled, winced, and said, “I’m sorry?” like a question.

Valentina lightly backhanded Cleo’s shoulder and said, “Don’t be sorry.”

“Can’t his name be the Tall Kid?” I asked.

“Another one, trying to rewrite the screenplay already,” Valentina said. “You don’t need to go on a diet per se, but if you want to go method, really dig into your character, you could go easy on the pizza and beer for the next two months, maybe even lose five or ten pounds, that would be ideal.”

Cleo said, “Jesus, Valentina!”

“What? I’m just saying. Not the rest of his life, just for the shoot. The thinner the better for this role.”

I’d had no idea what this meeting with Valentina would have wrought, but I’d not envisioned being asked to lose weight. I was 6’4" and 175 pounds, maybe, and I was self-conscious about how thin I was and always had been. “Self-conscious” isn’t strong enough. I hated my body, how stubbornly underdeveloped it was. No need to rehash the bullying I’d endured in middle school and the variety of nicknames that I never had the choice to approve in high school. Seemed I was one of those people destined for nicknames, including Weird Guy. That one I enjoyed, but it was hard not to itemize and take them all personally. My character name wasn’t exactly a nickname, but it might as well have been. It’s how people knew me then and how they know me now.

I again wanted to get up from the table and run away and ignore any further calls from Valentina, maybe unplug my phone, move away, change my name and identity. I said, “But pizza is a food group.”

“Do not listen to her,” Cleo said. She sounded more horrified than I was.

“Hey, I’m just kidding,” Valentina said in a way that I interpreted, correctly, as she wasn’t kidding.

After a few beats of awkward silence, Valentina talked a bit more about the production and how I’d need to be available and on-set for four weeks, at the most six weeks if things didn’t go to plan. She asked, “Will you be able to take leave from your job? Um, what are you doing now, anyway? Sorry, I guess I should’ve asked that earlier.”

After graduation I had gone home to Beverly. My parents were separated, and that spring Mom had moved to an apartment on the other side of town. The house in which I grew up was a sad and angry place haunted by the arguments and recriminations that had intensified during my four-year absence. I needed to move out as soon as I could, and to do that I needed a job. I hadn’t spent my last college semester writing a résumé and lining up interviews; consequently, I didn’t have any leads or any idea what I wanted to do. No one was going to pay me to play Nintendo all day, which was a shame. I signed up with a temp agency, requesting manual-labor jobs, like the Shoe Factory packing and stacking work I’d done the previous four summers. I would’ve gone back if the factory hadn’t closed. The temp agency assigned me to a grocery chain’s warehouse, and the first week I unloaded hundred-pound slabs of frozen beef from trailers and stacked them onto pallets. I, or more specifically, my cranky lower back, wasn’t