9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

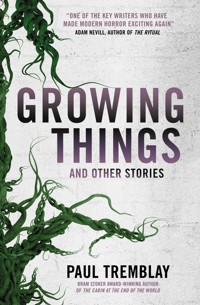

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A chilling short story collection by the Bram Stoker Award-winner author, including stories set in the world of A Head Full of Ghosts and Disappearance at Devil's Rock. A thrilling new collection from the award-winning author of A Head Full of Ghosts and The Cabin at the End of the World bringing his short stories to the UK for the first time. Unearth nineteen tales of suspense and literary horror, including a new story from the world of A Head Full of Ghosts, that offer a terrifying glimpse into Tremblay's fantastically fertile imagination. See a school class haunted by a life-changing video, the forces at work on four men fleeing the pawn shop they robbed at gunpoint, the meth addict kidnapping her daughter as the town is terrorized by a giant monster, or the woman facing all the ghosts who scare her most in a Choose Your Own Adventure. Intricate, humane, ingenious and chilling, embrace the Growing Things.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 577

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by Paul Tremblay and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

GROWING THINGS

SWIM WANTS TO KNOW IF IT’S AS BAD AS SWIM THINKS

SOMETHING ABOUT BIRDS

THE GETAWAY

NINETEEN SNAPSHOTS OF DENNISPORT

WHERE WE ALL WILL BE

THE TEACHER

NOTES FOR “THE BARN IN THE WILD”

__________

OUR TOWN’S MONSTER

A HAUNTED HOUSE IS A WHEEL UPON WHICH SOME ARE BROKEN

IT WON’T GO AWAY

NOTES FROM THE DOG WALKERS

FURTHER QUESTIONS FOR THE SOMNAMBULIST

THE ICE TOWER

THE SOCIETY OF THE MONSTERHOOD

HER RED RIGHT HAND

IT’S AGAINST THE LAW TO FEED THE DUCKS

THE THIRTEENTH TEMPLE

Notes

Acknowledgments

Credits

Also Available from Titan Books

OUTSTANDING ACCLAIM FOR PAUL TREMBLAY ON THE CABIN AT THE END OF THE WORLD

“A tremendous book – thought provoking and terrifying, with tension that winds up like a chain... Tremblay’s personal best. It’s that good.”

STEPHEN KING

“Paul Tremblay loads emotion and tension into every paragraph on every page of The Cabin at the End of the World. It’s not just that you don’t want to put the book down. It’s that rare feeling when the book won’t let go of you. Tremblay’s Cabin is a dream come true, a heartfelt, emotionally charged journey into our worst nightmares.”

CAROLINE KEPNES, AUTHOR OF YOU AND PROVIDENCE

“This is his finest work yet – which is saying much considering what has gone before – one that places characters into situations that show their love for each other and reveal the sacrifices they’re willing to make for that bond to endure.”

STARBURST

“A blinding tale of survival and sacrifice.”

KIRKUS

“Like the great horror novels of the 1970s and 1980s, Tremblay’s novels are social melodramas, employing the conventions of the horror field to dramatize and explore the conditions which threaten the contemporary family.”

LOCUS

ON A HEAD FULL OF GHOSTS

“Crackling with dark energy and postmodern wit r. . . [this] superb novel evokes the very best in the tradition—from Shirley Jackson to Mark Z. Danielewski and Marisha Pessl—while also feeling fresh and utterly new. Deeply funny and intensely terrifying, it’s a sensory rollercoaster and not to be missed.”

MEGAN ABBOTT, AUTHOR OF THE FEVER AND YOU WILL KNOW ME

“Paul Tremblay’s terrific A Head Full of Ghosts generates a haze of an altogether more serious kind: the pleasurable fog of calculated, perfectly balanced ambiguity.”

NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

“Tremblay paints a believable portrait of a family in extremis emotionally as it attempts to cope with the unthinkable, but at the same time he slyly suggests that in a culture where the wall between reality and acting has eroded, even the make believe might seem credible. Whether psychological or supernatural, this is a work of deviously subtle horror.”

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY (starred review)

“Brilliantly creepy.”

LIBRARY JOURNAL

“Progressively gripping and suspenseful — Tremblay’s ultimate, bloodcurdling revelation is as sickeningly satisfying as it is masterful.”

NPR BOOKS

GROWING THINGS

AND OTHER STORIES

ALSO BY PAUL TREMBLAY AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

The Cabin at the End of the World

Disappearance at Devil’s Rock

A Head Full of Ghosts

Growing Things and Other Stories

Print edition ISBN: 9781785657849

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785657856

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: July 2019

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2019 by Paul Tremblay. All rights reserved.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The St. Pierre Snake Invasion for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Sex Dungeons & Dragons,” words and music by The St. Pierre Snake Invasion © 2015.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For the (not so) little ones

Tears water our growth.

William Shakespeare

What terrified me will terrify others . . .

Mary Shelley

Daddy’s gonna show me the monsters.

Mummy’s gonna show me the creeps.

The St. Pierre Snake Invasion, “Sex Dungeons & Dragons”

GROWING THINGS

1.

Their father stayed in his bedroom, door locked, for almost two full days. Now he paces in the mudroom, and he pauses only to pick at the splintering doorjamb with a black fingernail. Muttering to himself, he shares his secrets with the weather-beaten door.

Their father has always been distant and serious to the point of being sullen, but they do love him for reasons more than his being their sole lifeline. Recently, he stopped eating and gave his share of the rations to his daughters, Marjorie and Merry. However, the lack of food has made him squirrelly, a word their mother—who ran away more than four years ago—used liberally when describing their father. Spooked by his current erratic behavior, and feeling guilty, as if they were the cause of his suffering, the daughters agreed to keep quiet and keep away, huddled in a living room corner, sitting in a nest of blankets and pillows, playing cards between the couch and the silent TV with its dust-covered screen. Yesterday, Merry drew a happy face in the dust, but Marjorie quickly erased it, turning her palm black. There is no running water with which to wash her hands.

Marjorie is fourteen years old but only a shade taller than her eight-year-old sister. She says, “Story time.” Marjorie has repeatedly told Merry that their mother used to tell stories, and that some of her stories were funny while others were sad or scary. Those stories, the ones Merry doesn’t remember hearing, were about everyone and everything.

Merry says, “I don’t want to listen to a story right now.” She wants to watch her father. Merry imagines him with a bushy tail and a twitchy face full of acorns. Seeing him act squirrelly reinforces one of the few memories she has of her mother.

“It’s a short one, I promise.” Marjorie is dressed in the same cutoff shorts and football shirt she’s been wearing for a week. Her brown hair is black with grease, and her fair skin is a map of freckles and acne. Marjorie has the book in her lap. All Around the World.

“All right,” Merry says, but she won’t really listen. She’ll continue to watch her father, who digs through the winter closet, throwing out jackets, itchy sweaters, and snow pants. As far as she knows, it is still summer.

The vibrant colors of Marjorie’s book cover are muted in the darkened living room. Candles on the fireplace mantel flicker and dutifully melt away. Still, it is enough light for the sisters. They are used to it. Marjorie closes her eyes and opens the book randomly. She flips to a page with a cartoon New York City. The buildings are brick red and sea blue, and they crowd the page, elbowing and wrestling each other for the precious space. Merry has already colored the streets green with a crayon worn down to a nub smaller than the tip of her thumb.

They are so used to trying not to disturb their father, Marjorie whispers: “New York City is the biggest city in the world, right? When it started growing there, it meant it could grow anywhere. It took over Central Park. The stuff came shooting up, crowding out the grass and trees, the flower beds. The stuff grew a foot an hour, just like everywhere else.”

Yesterday’s story was about all the farms in the Midwest, and how the corn, wheat, and soy crops were overrun. They couldn’t stop the growing things and that was why there wasn’t any more food. Merry had heard her tell that one before.

Marjorie continues, “The stuff poked through the cement paths, soaked up Central Park’s ponds and fountains, and started filling the streets next.” Marjorie talks like the preacher used to, back when Mom would force them all to make the trip down the mountain, into town and to the church. Merry is a confusing combination of sad and mad that she remembers details of that old, wrinkly preacher, particularly his odd smell of baby powder mixed with something earthy, yet she has almost no memory of her mother.

Marjorie says, “They couldn’t stop it in the city. When they cut it down, it grew back faster. People didn’t know how or why it grew. There’s no soil under the streets, you know, in the sewers, but it still grew. The shoots and tubers broke through windows and buildings, and some people climbed the growing things to steal food, money, and televisions, but it quickly got too crowded for people, for everything, and the giant buildings crumbled and fell. It grew fast there, faster than anywhere else, and there was nothing anyone could do.”

Merry, half listening, takes the green crayon nub out of her pajama pocket. She changes her pajamas every morning, unlike her sister, who doesn’t change her clothes at all. She draws green lines on the hardwood floor, wanting their father to come over and catch her, and yell at her. Maybe it’ll stop him from putting on all the winter clothes, stop him from being squirrelly.

Their father waddles into the living room, breathing heavily, used air falling out of his mouth, his face suddenly hard, old, and gray, and covered in sweat. He says, “We’re running low. I have to go out to look for food and water.” He doesn’t hug or kiss his daughters but pats their heads. Merry drops the crayon nub at his feet, and it rolls away. He turns and they know he means to leave without any promise of returning. He stops at the door, cups his mittened and gloved hands around his mouth, and shouts toward his direct left, into the kitchen, as if he hadn’t left his two daughters on their pile of blankets in the living room.

“Don’t answer the door for anyone! Don’t answer it! Knocking means the world is over!” He opens the door, but only enough for his body to squeeze out. The daughters see nothing of the world outside but a flash of bright sunlight. A breeze bullies into their home, along with a buzz-saw sound of wavering leaves.

2.

Merry sits, legs crossed, a foot away from the front door. Marjorie is back in the blanket nest, sleeping. Merry draws green lines on the front door. The lines are long and thick, and she draws small leaves on the ends. She’s never seen the growing things, but it’s what she imagines.

The shades are pulled low, drooping over the sills like limp sails, and the curtains are drawn tight. They stopped looking outside after their father begged them not to, and they won’t look out the windows now that he’s not here. When it first started happening, when their father came home with the pickup truck full of food and other supplies, he stammered through complex and contradictory answers to his daughters’ many questions. His knotty hands moved more than his lips, removing and replacing his soot-stained baseball cap. Merry mainly remembers that he said something about the growing things being like a combination of bamboo and kudzu. Merry tugged on his flannel shirtsleeve and asked what bamboo and kudzu were. Their father smiled but also looked away quickly, like he’d said something he shouldn’t have.

Outside the wind gusts and whistles around the creaky old cabin. The mudroom and living room windows are dark rectangles outlined in a yellow light, and their glass rattles in the frames. Merry stares at the wooden door listening for a sound she’s never heard before: a knock on her front door. She sits and listens until she can’t stand it any longer. She runs upstairs to her bedroom, picks out a pair of new pajamas, changes again in the dark, and carefully folds the dirty set and places it back in her bureau. Merry then returns to the nest and wakes her older sister.

“Is he coming back? Is he running away, too?”

Marjorie comes to and rises slowly. She lifts the book from her lap and hugs it to her chest. Her fingers crinkle the edges of the pages and worry the cardboard corners of the cover. Despite the acne, she looks younger than her fourteen.

Marjorie shakes her head, answering a different question, one that wasn’t spoken, and says, “Story time.”

Merry used to enjoy the stories before they were always about the growing things. Now she wishes that Marjorie would stop with the stories, wishes that Marjorie could just be her big sister and quit trying to be like their mother.

“No more stories. Please. Just answer my questions.”

Marjorie says, “Story first.”

Merry balls her hands into fists and fights back tears. She’s as angry now as she was when Marjorie told all the kids at the playground in town that Merry liked to catch spiders and rip off each leg with tweezers, and that she kept a jar of their fat legless bodies in her bureau.

“I don’t want to hear a story!”

“I don’t care. Story first.”

Marjorie always gets her way, even now, even as she continues to withdraw and fade. She leaves the nest only to go to the bathroom, and she walks like an older woman, the joints and muscles in her legs stiff with disuse.

Merry asks, “You promise to answer my questions if I listen to a story?”

All Marjorie says is “Story first. Story first.”

Merry isn’t sure if this is a yes or a maybe.

Marjorie tells of the areas around the big cities, places called the suburbs. How the stuff ruined everyone’s pretty lawns and amateur gardens, then started taking root in the cracks of sidewalks and driveways. People poured and sprayed millions of gallons of weed killer, Liquid-Plumr, lye, and bleach. None of it worked on the stuff, and all the chemicals leached into the groundwater, which flowed into drinking-water reservoirs, poisoning it all.

Like most of Marjorie’s stories, Merry doesn’t understand everything, like what groundwater is. But she still understands the story. It makes a screaming noise inside her head, and it is all that she can do to keep it from coming out.

She says, “I listened to your story, now you have to answer my question, okay?” Merry takes the book away from Marjorie, who surprisingly does not resist.

“I’m tired.” Marjorie licks her dry and cracked lips.

“You promised. When is he coming back?”

“I don’t know, Merry. I really don’t.” With the blankets curled and twisted around her legs and arms, it’s as if she’s been pulled apart and her pieces sprinkled about their nest.

Merry wants to shrink and crawl inside one of her sister’s pockets. She asks in her smallest voice, “Was this how it happened last time?”

“What last time? What are you talking about?”

“When Mommy ran away? Was this how it happened when she ran away?”

“No. She wasn’t happy, so she left. He’s going to get food and water.”

“Is he happy? He didn’t look happy when he left.”

“He’s happy. He’s fine. He isn’t leaving us.”

“He’s coming back, though, right?”

“Yes. He’ll come back.”

“Do you promise?”

“I promise.”

“Good.”

Merry believes in her big sister, the one who once punched a third grader named Elizabeth in the nose for putting a daddy longlegs down the back of Merry’s shirt.

Merry leaves the nest and resumes her post, sitting cross-legged in the mudroom, in the shadow of the front door. The wind continues to increase in velocity. The house stretches, settles, and groans, the sounds eager for their chance to fill the void. Then, on the other side of the front door, brushing against the wood, there’s a light rapping, a knocking, but if it is a knocking, it’s being done by doll-sized hands with doll-sized fingertips small enough to find the cracks in the door that nobody can see, small enough to get inside the door and come through on the other side. The inside.

Merry stays seated, but twists and yells, “Marjorie! I think someone is knocking on the door!” Merry covers her mouth, horrified that whoever is knocking must’ve heard her. Even in her terror, she realizes the gentle sounds are so slight, small, quiet, that maybe she’s making up the knocking, making up her very own story.

Marjorie says, “I don’t hear anything.”

“Someone is knocking lightly. I can hear them.” Merry presses her ear against the wood, closes her eyes, and tries to finish this knocking story. Single knocks become a flurry issued by thousands of miniature doll hands, those faceless toys, maybe they crawled all the way here from New York City, and they scramble and climb over each other for a chance to knock the door down. Merry wraps her arms around her chest, terrified that the door will collapse on top of her. The knocking builds to a crescendo, then ebbs along with the dying wind.

Merry rests her forehead on the door and says, “It stopped.”

Marjorie says, “No one’s there. Don’t open the door.”

3.

Marjorie hasn’t eaten anything in days. They are down to a handful of beef jerky and a half-box of Cheerios. In the basement, there are only two one-gallon bottles of water left, and they rest in a corner on the staircase landing. Flashlight in hand, Merry sits on the damp wood of the landing, plastic water jugs pressing against her thigh. It’s cooler down here, but her feet sweat inside her rubber rain boots. The boots are protection in case she decides to walk toward the far wall and hunt for jars of pickles or preserves her father may have stashed.

Merry has been sitting with her flashlight pointed at the earthen floor for more than two hours. When she first came down here, the tips of the growing things were subtle protrusions; hints of green and brown peeking through the sun-starved dirt. Now the tallest spearlike stalks stretch for more than a foot above the ground. The leafy ends of the plants would tickle her knees were she to take the trip across the basement. She wonders if the leaves would feel rough against her skin. She wonders if the leaves are somehow poisonous, despite never having heard her sister describe them that way.

Earlier that morning, Merry decided she had to do something other than stare at the front door and listen for the knocking. She put herself to work and rearranged the candles around the fireplace mantel, and she lit new ones, although, according to her father, she wasn’t old enough to use matches. She singed the tips of her thumb and pointer finger watching that first blue flame curl up the matchstick. After the candles, she prepared a change of clothes for Marjorie and left the small bundle, folded tightly, on the couch. She picked out a green dress Marjorie never wore but Merry not-so-secretly coveted. Then she swept the living room and kitchen floors. The scratch of the broom’s straws on the hardwood made her uneasy.

Marjorie slept most of the day, waking only to tell a quick story of the growing things cracking mountains open like eggs, drowning the canyons and valleys in green and brown and drinking up all the ponds, lakes, and rivers.

Merry runs the beam of her flashlight over the stone-and-mortar foundation walls but sees no cracks and scoffs at the most recent tale of the growing things. Marjorie’s stories had always mixed truth with exaggeration. For example, it was true that Merry used to hunt and kill spiders, and it was true all those twitchy legs were why she killed them. Simply watching a spider crawling impossibly on the walls or ceiling and seeing all that choreographed movement set off earthquake-sized tremors somewhere deep in her brain. But she was never so cruel as to pull off their legs with tweezers, and she certainly never collected their button-sized bodies. Merry never understood why Marjorie would say those horrible, made-up things about her.

Still, Merry initially believed Marjorie’s growing things stories, believed the growing things were even worse than what Marjorie portrayed, which is what frightened Merry the most. Now, however, seeing the sprouts and stalks living in the basement makes it all seem so much less scary. Yes, they are real, but they are not city-dissolving, mountain-destroying monsters.

Merry thinks of an experiment, a test, and shuts off the flashlight. She hears only her own breathing, a pounding bass drum, so big and loud it fills her head, and in the absolute dark, her head is everything. Recognizing her body as the source of all that terrible noise is too much and she starts to panic, but she calms herself down by imagining the sounds of the tubular wooden stalks growing, stretching, reaching out and upward. She turns the flashlight on again, surveys the earthen basement floor, and she’s certain there has been more growth and new sprouts emerging from the soil. The sharp and elongated tips of the tallest stalks sport clusters of shockingly green leaves the size of playing cards, the ends of which are also tapered and pointed. The stalks grow in tidy, orderly rows, although the rows grow more crowded and the formations more complex as the minutes pass. Merry repeats turning off the flashlight, sitting alone in the dark, breathing, listening, and then with the light back on, she laughs and quietly claps a free hand against her leg in recognition of the growing things’ progress.

Merry indulges in a fantasy where her father returns home unharmed, arms loaded with supplies, a large happily-ever-after smile on his sallow face, and he’s not squirrelly anymore.

The daydream ends abruptly. In a matter of days her father has become unknowable, unreachable; a single tree in a vast forest, or a story she once heard but has long forgotten. Was this how it happened with Marjorie and their mother? Her sister was around the same age as Merry is now when their mother ran away. To Merry, their mother is a concept, not a person. Will the same dissociation happen with their father if he doesn’t come back? Merry fears that memories of him, even the small ones, will recede too far to ever be reached again. Already, she greedily clutches stored scenes of the weekly errands she ran with her father this past spring and summer while Marjorie was at a friend’s house, how at each stop he walked his hand across the truck’s bench seat and gave her knee a monkey bite, that is unless she slapped his dry, rough hand away first, and then the rides home, how he let both daughters unbuckle their belts for the windy drive home up the mountain, Merry sandwiched in the middle, so they could seesaw-slide on the bench seat along with the turns. Did he only tolerate their wild laughter and mock screams as they slid into each other and him, hiding a simmering disapproval, or did he join the game, leaning left and right along with the truck, adding to the chorus of his daughters’ screams? She already doesn’t remember. Merry cannot verbalize this, but the idea of a world where people disappear like days on a calendar is what truly terrifies her, and she wants nothing more than for herself and her loved ones to remain rooted to a particular spot and to never move again.

Merry considers asking Marjorie all these questions about her parents and more, but she’s worried about her sister. Marjorie is getting squirrelly. Marjorie didn’t even open the book for this morning’s story. And when Merry left the living room to go to the basement, Marjorie was sleeping again, her eyelids as purple as plums. What if Marjorie runs away, too, and leaves her all alone?

Merry puts the flashlight down on the landing, leaving it on and centering its yellow beam in an attempt to illuminate as much of the basement floor as possible. She lifts a one-gallon water bottle and peels away the plastic ring around the cap, then steps off the landing and walks toward the middle of the floor, unable to see anything below her ankles, which is as low as the focused beam of light hits. Under her feet, the disturbed and clotted earth feels lumpy and even hard in places, a message in Braille she cannot decipher. She hopes she is not stepping on any of the new shoots.

She pries off the cap, jarring the balance of the bottle in her arms, spilling water onto her hand and her pajama shorts. Her forearms tremble with the bulky jug set in the crooks of her pointy elbows. Water continues to spill out and gathers on the leaves. She knows they can’t spare much, so she pours out only a little, then a little more, hoping the water reaches the roots.

Merry puts the cap on the bottle and walks back to the landing. She’ll take the water upstairs, pour two cups, and give one to her sister, force her to drink. Then she’ll curl up in the nest with Marjorie and sleep, thinking about her plants in the basement. She will do all that and more, but only after she sits on the landing, shuts off the flashlight, listens in the dark to the song of the growing things, and listens some more, and then, eventually, turns the flashlight back on.

4.

She did not blow out the candles before collapsing and falling asleep on their nest of blankets. All but three candles have burnt out or melted away. Wax stalactites hang from the fireplace mantel. Merry wakes on her left side and is nose to nose with her sister. Having gone many days without being able to bathe or wash, Marjorie’s acne has intensified, ravaging her face. Whiteheads and hard, painful-looking red bumps mottle her skin, creating the appearance of fissures, as if her grease-slicked face is a mask on the verge of breaking up and falling away. Merry wonders if the same will happen to her.

Marjorie opens her eyes; her pupils and deep brown irises are almost indistinguishable from each other. She says, “The growing things will continue to grow until there aren’t any more stories.” Her voice is scratchy, obsolete, packed away somewhere inside her chest like a holiday sweater, a gift from some forgotten relative.

Merry says, “Please don’t say that. There will be more stories and you have to tell them.” She reaches out to hug her sister, but Marjorie buries her face in a blanket and tightens into a ball.

Merry asks, “How are you feeling today, Marjorie? Did you drink your water?” On the end table between them and the couch is the answer to her question: the glass of water she poured last night is full. “What are you doing, Marjorie? You have to drink something!” A sudden all-consuming anger wells up in Merry and she alternates between hitting her sister and tearing the layers of blankets and sheets away from the nest. It comes apart easily. She throws All Around the World over her head. It thuds somewhere behind her. Marjorie doesn’t move and remains curled in her ball, even after Merry dumps the water on her head.

Merry kneels beside her prone sister and covers her face in her hands, hiding what she’s done from herself. Eventually she musters the courage to look again, and she says, “Tell me a story about our father, Marjorie. About him coming back. Please?”

“There are no more stories.”

Merry pats Marjorie’s damp shoulder and says, “No. It’s okay. I’m sorry. I’ll clean this up, Marjorie. I can fix this.” She’ll gather their nest blankets and sheets, and she’ll dry her sister and force her to change out of the wet clothes and into the green dress, then they’ll really talk about what to do, where they should go if their father isn’t coming back.

Merry stands and turns around. The nest blankets Merry threw into the middle of the living room have become three knee-high tents, each sporting sharp, abrupt poles raising the cloth above the floor. The poles don’t waver and appear to be supremely sturdy, as if they would stand and continue standing regardless of whether the world fell apart around them.

Merry puts her fingers in her mouth. Everything in the living room is quiet. She whispers Marjorie’s name at the tents, as if that is their name. She bends down slowly, grabs the plush corners of the blankets, and pulls them away quickly, the flourish to a magician’s act. Three stalks and their tubular wooden trunks have penetrated the living room floor, along with smaller tips of other stalks beginning to poke through. The hardwood floor is the melted wax of the candles. The hardwood floor is the poor blighted skin of Marjorie’s face. Warped and cracked, curling and bubbling up, the floor is a landscape Merry no longer recognizes.

She believes with a child’s unwavering certainty that this is all her fault because she watered the growing things in the basement. Merry tries to pull Marjorie up off the floor but can’t. She says, “We can’t stay down here. You have to go upstairs. To our room. Go upstairs, Marjorie! I’ll get the rest of the water.” She wants to confess to having poured almost half the one-gallon jug on the growing things, but instead she says, “We’ll need the water upstairs, Marjorie. We’ll be very, very thirsty.”

Merry maps out a set of precise steps. The newly malformed floorboards squawk and complain under her careful feet. Green leaves and shoots on the tips of the exposed stalks whisper against her skin as she makes her too-slow progress across the living room. She imagines going so slow that the stalks continue to grow beneath her, pick her up like an unwanted hitchhiker and carry her through the ceiling, the second-floor bedrooms, and then the roof of the house, and into the clouds, then farther, past the moon and the sun, to wherever it is they’re going.

Merry pauses at the edge of the living room and kitchen, near the mudroom, and there is someone rapping on the front door again. The knocking is light, breezy, but insistent, frantic. She’s not supposed to open the door, and despite her absolute terror, she wants to, almost needs to open the door, to see who or what is on the other side. Instead, Merry turns and yells back to Marjorie, who hasn’t moved from her spot. Merry urges her to wake, to go upstairs where they’ll be safe. There are shoots and stalk tips breaking through the floor in the area of the nest now.

Merry runs into the kitchen, and while there are the beginnings of stalk tips in the linoleum, the damage doesn’t appear as severe as it is in the living room. She takes the flashlight off the counter and opens the door to the basement stairwell. She expects a lush, impenetrable forest in the doorway, but the stairs are still there and very much passable; her own path into the basement, to her garden, is preserved. She ducks under one thick wooden stalk that acts as a beam, outlining the length of ceiling, and she descends to the landing, where the bottles of water remain intact.

Once on the landing, which is pushed up like a tongue trying to catch a raindrop or a snowflake, Merry adjusts her balance and gropes for the water bottles. She tries picking up both, but she’s only strong enough to take the one full bottle and hold the flashlight at the same time. She contemplates making a second trip, but she doesn’t want to go back down here. The half-full second bottle will have to be a sacrifice.

Before going up the stairs, she points her flashlight into the heart of the basement, starting at the floor, which is green with countless new shoots. She aims the flashlight up and counts twelve stalks making contact with the ceiling, then traces their lengths downward. The tallest stalks have large clumps of dirt randomly stuck and impaled upon their wooden shafts. There are six clumps; she counts them three times. One clump is as big as a soccer ball but is more oval shaped. Four of the other dirt clods are elongated, skinny, curled, and hang from the stalks like odd overripened and blackened vegetables. Three stalks in the middle of the basement share and hold up the largest of the dirt formations; rectangular and almost the size of Merry herself, it’s pressed against the ceiling.

Merry rests the flashlight beam on this last and largest dirt clod. Something else is hanging from it, almost dripping or leaking out of the packed dirt. After staring for as long as she can stare, and as her house breaks into pieces above her, Merry realizes what she is looking at is a swatch of cloth, perhaps the hem of dress. She can almost make out its color. Green, maybe.

Although the previous night was more about the rush of her discovery of the growing things, and of her flashlight game, looking at the basement now and seeing what she sees, specifically the cloth, Merry remembers walking the basement floor in her rubber boots, walking on what she couldn’t see, the unexpectedly hard and lumpy soil, and she now knows she was walking upon the bones of the one who disappeared, of the runaway.

Merry shuts off the flashlight and throws it into the basement. Leaves rustle and there’s a soft thud. She climbs the stairs in the dark, thinking of all the bones beneath her feet. Merry is furious with herself for not recognizing those bones last night, but how could she be blamed? She never really knew her mother.

Merry runs up the basement steps into the kitchen and stumbles over and past the continued growth. The knocking on the front door is no longer subtle, no more a mysterious collection of dolls’ hands. The sound of the knocking is itself a force. It’s a pounding by a singular and determined fist, as big as her shrinking old world, maybe as big as the growing new one. The door rattles in the frame, and Merry screams out with each pounding.

She shuffles away from the mudroom and into the living room. Marjorie is still there but is up and out of the nest. She’s knelt between the stalks that have erupted through the floor. She pinches the shoots and leaves between her fingers, plucks them away, and puts them in her mouth.

The pounding on the front door intensifies. Her father said if there was a knocking on the door, then the world was over. A voice now accompanies the unrelenting hammering on the door. “Let me in!” The voice is as ragged and splintered as the living room floor.

Merry shouts, “We need to go upstairs, Marjorie! Now now now!”

More pounding. More screaming. “Let me in!”

Merry imagines the growing things gathered outside her door, weaved into a fist as big as their house. The leaves shake in unison and in rhythm, their collected rustling forming their one true voice.

Merry imagines her father outside the door. The one she never knew, eyes wide, white froth and foam around his mouth, spitting his demand to be allowed entry into his home, the place he built, the place he forged out of rock, wood, and dirt—all dead things. His three-word command is what heralds the end of everything. She imagines her father breaking the door down, seeing his oldest daughter eating the leaves that won’t stop growing, and seeing what his youngest daughter knows is written on her face as plain as any storybook.

Marjorie doesn’t look at her sister as she gorges on the leaves and shoots. Then Marjorie stops eating abruptly, her head tilts back, her eyelids flutter, and she falls to the floor.

Merry drops the water jug, covers her ears, and goes to Marjorie, even if Marjorie was wrong about there being no more stories.

Merry tells Marjorie another story. Merry will get her up and take her upstairs to their bedroom. She’ll let Marjorie choose what she wants to wear instead of trying to force the green dress on her. They’ll always ignore the pounding on the door, and when they’re safe and when everything is okay, Merry will ask Marjorie two questions: What if it isn’t him outside the door? What if it is?

SWIM WANTS TO KNOW IF IT’S AS BAD AS SWIM THINKS

What I remember from that day is the road. It went on forever and went nowhere. The trees on the sides of the road were towers reaching up into the sky, keeping us boxed in, keeping us from choosing another direction. The trees had orange leaves when we started and green ones when it was over. The dotted lines in the middle of the road were white the whole time. I followed those, carefully, like our lives depended on them. I believed they did.

We made the TV news. We made a bunch of papers. I keep one of the clippings folded in my back pocket. The last line is underlined.

“The officer said the police don’t know why the mother headed south.”

* * *

I need a smoke break bad. My fingertips itch thinking about it. It’s an early-afternoon Monday shift and I’m working the twelve-items-or-less register, which sucks because it means I don’t get a bagger to help me out. Not that today’s baggers are worth a whole heck of a lot. I don’t want Darlene working my line.

We’ve never met or anything, but Julie’s youth soccer coach, I know who he is. Brian Jenkins, a townie like me, five years older but looks five years younger, a tall and skinny schoolteacher type even if he only clerks for the town DPW, wearing those hipster glasses he doesn’t need and khakis, never jeans. Always easy with the small talk with everyone in town but me. Brian isn’t paying attention to what he’s doing, lost in his own head like anyone else, and he gets in my line with his Gatorade, cereal, Nutter Butters, toothpaste, and basketful of other shit he can’t live without. Has a bag of oranges, too. He’ll cut them into wedges like those soccer coaches are supposed to. I’m not supposed to go to her games, so I don’t. From across the street I’ll walk by the fields sometimes and try to pick out Julie, but it’s hard when I don’t even know what color shirt her team wears. When Brian sees it’s me dragging that bag of oranges over the scanner, me wondering which orange Julie will eat, sees it’s me asking if he has a Big Y rewards card, and I ask it smiling and snapping my gum, daring him to say something, anything, he can barely look me in the eye. Run out of things to say in my line, right, coach?

I get recognized all the time, and my being seen without being seen is something I’m used to, but not used to, you know? I never signed up to be their bogeywoman. Yeah, I made a mistake, but that doesn’t mean they’re better than me, that I’m supposed to be judged by them all the time. It isn’t fair. Back when I could afford to see court-appointed Dr. Kelleher he’d tell me I’d need to break out of the negative-thoughts cycles I get stuck in. He was a quack who spent most of our sessions trying to look down my shirt, but I think he was right about breaking out of patterns. So when I start thinking like this I hum an old John Lennon tune to myself, the same one my mother used to walk around the house to, singing along. She’d drop me in front of the TV to do what she called her exercises. She’d put on her Walkman headphones that just about covered up her whole head, the music would be so loud she couldn’t hear me crying or yelling for her, that’s what she told me anyway, sorry honey, Momma can’t hear you right now, and she’d walk laps around the first floor of the house, she’d walk forever, bobbing her head and singing the same part of that Lennon tune over and over. So I find myself singing it now, too. The song helps to ease me out of it, whatever it is, sometimes. Sometimes it doesn’t.

I’m humming the song right now. The notes hurt my teeth and goddammit, I want my cigarette break. It’d take the edge off my fading buzz. I scratch my arms, both at once, so maybe it looks like I’m hugging myself to keep warm. It is cold in here, but I’m not cold.

Monday normally isn’t too busy, but there’s a nor’easter blowing, so the stay-at-home moms in their SUVs and all the blue-hairs are in, buzzing around the milk, juice, bread, cereal, cigarettes. Only three other lines open and they’re all backed up, so Tony the manager runs around, the sky is falling, and he runs his fingers through his nasty greasy comb-over, sending people to my line. Storm’s not supposed to be bad, but everyone’s talking to each other, gesturing wildly, checking their phones. I don’t listen to them because I don’t care what they have to say. I keep humming my Lennon tune to myself and I keep scratching my arms, making red lines.

Darlene’s fluttering around registers now, asking the other cashiers questions, eyes and mouth going wide, and she puts a hand to her chest like a bad actor. She’s checking her own phone. I don’t know how she can see it or knows how to use it. Everyone but me has one. Like Dr. Kelleher, I can’t fit a smartphone in my lifestyle anymore, financially speaking.

Tony sends Darlene down to me. Great. Not being mean or nothing, but she slows everything down. I end up having to bag almost everything for her anyway because she can’t see out of one eye and her hands shake and she doesn’t really have a gentle setting. Bagging isn’t where she should be, and none of the shoppers, even the ones who pretend to be friendly to her, want her pawing their groceries, especially when her nose is running, which is all the time. Basically they don’t want to deal with her at all. It’s so obvious when you have Darlene and then no one goes in your line even when the other lines are backed up into the aisles, and it sucks because I have to talk to her, and she’ll ask me questions the whole time about boyfriends and having kids. I don’t quite have it in me to tell her to leave me alone, to tell her to shut the fuck up with her kid questions. I guess she’s the only one in town who doesn’t know who I am.

The woman in the baggy gray sweatshirt and yoga pants stops her whispering with the woman behind her in my line now that I’m in earshot. I feel a stupid flash of guilt for no reason. I haven’t even done anything to anyone here yet, you know, and I hate them and I hate myself for feeling that way, like yeah of course it’s because of me and not a stupid little snowstorm that everyone is freaking out about in the Big Y. The woman says nothing to me, then takes over the bagging of her own stuff. She just about elbows Darlene out of the way, who for once doesn’t seem all that crazy about bagging groceries.

I can’t resist saying something now. “In a hurry? Leaving town?” I say the “leaving town” part almost breathlessly. Like it’s the dirty secret everyone knows.

“Oh. Yes. No. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry,” she says to Darlene but keeps on bagging her own groceries. Her hands shake. I know how that feels. I run the woman’s credit card and have a go at memorizing the sixteen numbers without being obvious about it. You know, just for fun.

Darlene doesn’t mind getting elbowed out of the way any. She’s staring at her phone, gasping and grunting like it hurts to look at. Humming my song isn’t working. Seeing Julie’s coach messed me up good.

Tony’s still directing traffic into the lines, which is totally useless. We’re all backed up and the customers are grumbling, looking around for more open lines. It’s as good a time as any for me to yell back to Tony that I have to take a break.

He opens his mouth to argue, to say no, you can’t now, but the look I give him shuts him down. He knows he can’t say no to me. He shuffles through the crowd to behind my register and takes my line. “Be quick,” he says.

“Maybe.” I grab my coat. It’s thinner than an excuse.

Then he says something under his breath, something about not knowing what’s going on here, not that I’m listening anymore.

Darlene with all her fidgeting, customers rushing around the aisles, cramming into the lines, just about sprinting out of the store, hits me all at once, and for a second it’s like all the times I’ve blacked out, then woken up with that feeling of oh shit, I wasn’t me again, and the me who wasn’t me did something, something wrong, but I don’t know what. Like that one time in my newspaper clipping when, just like the cops, I didn’t know why the crazy wasn’t-me chick was going south with my daughter either.

I say to Darlene, “Can I see what you’re watching, darling?” and I try to grab her phone. No go. Darlene has a death grip on the thing, and she taps my hand three times. Same OCD tap routine she goes through with the customers. Sometimes she’ll tap the box of Cheerios before stuffing it into a bag, paper or plastic, or she’ll tap the credit card if I leave it out next to the swipe pad instead of putting it back in the customer’s hand.

She says, “It’s a news video. Something terrible is happening. Something weird came out of the ocean.” Then she whispers, “Looks like giant monsters!”

“Well, I gotta see that, don’t you think? Show me. Don’t worry, I won’t grab again. You hold the phone for me and I’ll watch.”

I try and get close to Darlene but she’s always flailing around like a wind chime in a storm. The video plays on the phone but she obsessively moves the little screen away from me and when I try to hold her still she clucks and starts in with tapping me again so I can’t see much. What little I see looks like footage from one of the cable networks. A news ticker crawls along the bottom of the screen. Can’t make out the words. I think I see what looks like giant waves crashing into shoreline homes, and then a dark shape, smudge, shadow, something above it all, and maybe it has arms that reach and grab, and Darlene squeals out, “Oh my god, there it is!” and starts pacing a tight circle around nothing.

“Hey, I don’t think that’s the real news, hon. It’s fake. Pretend, yeah? I bet it’s a trailer for a new movie. Isn’t there a monster movie coming out soon, right? Next summer. There’s always a big monster movie coming out in the summer.”

“No. No no no. It’s the news. It’s happening. Everyone’s talking about it. Aren’t you talking about it, too?”

Tony shouts over to me, “What are you doing?”

That’s enough to chase me out. I wave bye-bye with my cigarette pack, the one with a little hit of yaba tucked inside. I say, “Don’t wait up,” loud enough for myself, and I walk through the sliding doors and outside. I’m supposed to have four more hours on my shift. It’ll be dark then. Who needs it. I’m still humming.

The snow is falling already, slushing up the parking lot. I dry-swallow the yaba that I wrapped in a small strip of toilet paper, I imagine it crashing into my stomach like an asteroid. Then I light up a cig. Breathe fire. I close my eyes because I want to, and when I open them I’m afraid I’ll see Julie’s coach waiting for me in the snowy lot. I’m afraid he’ll tell me to stay away from the soccer fields. I’m afraid he and the whole town know I’m not supposed to get within two hundred yards of Julie’s house when I do it all the time. I’m not afraid of Darlene’s monsters. Not yet, anyway. I’m afraid of standing in front of the Big Y forever, but I’m afraid of leaving, too. I’m afraid it’ll be a snowy mess already at the bus stop. I’m afraid I didn’t wear the right shoes. I’m afraid I don’t know if Julie takes the bus home from school. I’m afraid of home. Mine and hers. They’re different now. But her home used to be my home. Julie calls my mother Gran. Gran won’t shop the Big Y anymore.

I’m still humming the song, through the tip of the cigarette now.

Christ, you know it ain’t easy.

You sing it, girl.

* * *

After the Big Y, I don’t go home. I take the bus to Tony’s place instead. Dumb-ass gave me a key. I put on a pair of his boots that are way too big. I drink a beer out of his fridge and pretend to eat some of his food. I check his bedroom dresser drawers for cash. Find the fist-sized handgun he’s waved in my face more than once and a wadded-up thirty-six dollars, which isn’t enough.

I’m not staying long. I have to go to the house again tonight. I have no choice. Living without choice is easier.

First I jump on Tony’s computer and go online to the User Forum. It’s a message board. It’s anonymous and free. Both are good, because, you know, it’s up to me to keep me safe, to keep me not dead. My handle is notreallyhere and yesterday I posted a question.

NOTREALLYHERE

eating meth

swim wants to know if swallowing yaba messes up your stomach bad. swim or people swim knows eat it occasionally, sometimes on an empty stomach, which probably isn’t good, or swim knows it isn’t good but wants to know if it’s really as bad as swim thinks. using toilet paper help? hurt?

I call myself “swim,” which stands for someone who isn’tme. I use swim even though it’s against the forum rules to use it. Everyone else uses it, too, so swim is kind of a joke. The first response is confusing.

DOCBROWNSTONE

Re: eating meth

SWIM has done this before and the toilet paper, too. Little amounts dont do much and make you constipated. Huge amounts make you super sick . . . SWIM puked for hours and SWIM buddy had stomach pumped. So easy to OD this way too. Super harsh, esp. the stomach. You eat it, it eats you. So play it safe with meth. Dont eat it, dont stick it in your asshole. You wont like either result.

I don’t know if DocBrownstone means little amounts of meth or little amounts of toilet paper make me constipated. I don’t care about constipation. If it becomes a problem I can cut it with a laxative. I never eat food anyway. I care only about the stomach pain that bends me in half like a passed note. There are three other responses.

BRAINPAN

re: eating meth

Better for you health wise to take orally cause it keeps blood serum levels low and keeps neurotoxicity low too. SWIy wants it, oh yes. Pepper some of one’s weight in their OJ or coffee in the AM and it’s all GO GO GO all day. Did Swibf say its smoother?

ENHANCION69

re: eating meth

Swim heard eating meth almost gets same IV high. Swim eats and high is longer and stronger, even with smaller amount.

SNYTHEEDICAL

re: eating meth

hey all you little swimmies out of the water. did you see? looks like its not safe anymore.

I can’t get past brainpan. He’s always all over these message boards and he pisses me off because he’s making me nervous and that makes my stomach hurt worse. I mean, there’s no way he knows what he’s talking about but he’s trying to fake it, always faking it. Like he can walk around measuring blood serum and neurotoxicity like ingredients in a batch of cupcakes. I get a twinge of hunger somewhere underneath all the pain. Maybe I should eat something. Maybe thinking about eating cupcakes is all I have to do to make everything better. Then that hunger pang from Christmases past turns into a machete ripping through my guts, and I’m standing up screaming, “Fuck you!” at the computer screen, at brainpan. I stumble back and knock Tony’s stupid computer chair over, so I stomp it with his boots, deader than it already is, and I push his keyboard, mouse, and all the stupid little shit he saves on his desktop to the floor and I rampage all over the stuff. I’ve never been thinner but I crush everything under my mighty mighty weight, and I’m still grinding it all under my heels when everything goes dark.

* * *

I tell Julie that a transformer blew out and it’s why there’s no electricity anywhere in town, and it’s why I came to get her, too.

I tell Julie there’s nothing to be afraid of.

I ask Julie if she remembers the Ewings and their tiny red house. It was even smaller than Gran’s house, but kept nicer. It used to be in the spot where we are now. Their house postage-stamped this big, hilly, wooded lot across the way from Gran’s. Mr. Ewing died six years ago, maybe seven, and Mrs. Ewing was shipped to a nursing home. Alzheimer’s. Her kids sold the house and plots of land to a local contractor. He knocked the little red house down, ripped out just about all the trees, leveled off and terraced the lot, and is building this huge twenty-five-hundred-square-foot colonial on the top of the hill. For months, I’ve been checking out the place, watching the progress. Makes me so sad for the Ewings. The contractor keeps the house key in the plastic molding that protects an outdoor outlet near the garage. I show Julie the bright blue key sleeve.

I tell Julie that when I was her age I used to run away from Gran’s house all the time, but I’d go only as far as across our street, past the corner, onto Pinewood Road, and to the Ewings’ house. The Ewings had five kids, but they were all grown and living on their own. I hardly ever saw them. After I hid from Gran and climbed trees in the Ewings’ yard for a bit, Mrs. Ewing would let me in and I’d chase her cat Pins around. Such a small house, one floor with only three bedrooms, and the kids’ beds still double-stacked up against the walls like planks. Pillows fluffed and sheets tightly made. It was like being in a giant dollhouse.

I tell Julie that Pins the cat loved when I chased her from bed to bed, up the walls and down. That black and white cat had a snaggletooth that stuck out beneath its upper lip. Pins let me touch the tooth, and it was sharp, but not like a pin, you know? I tell her that sometimes I pressed too hard on the tooth and we’d both cry out and then I’d say sorry and shush us both and say everything was fine.

I tell Julie I don’t think Mr. Ewing trusted me much and blamed me for the missing loose change jar he kept on his bureau and wanted to send me home whenever he could, but Mrs. Ewing was so nice and would say, “Bill,” all singsong. That way she said “Bill” made my ears and cheeks go red because she was really saying something about me, or me and your gran. I didn’t understand what it was back then. Then Mrs. Ewing would make me PB and J sandwiches. She must’ve bought the apple jelly just for me since her kids were long gone.

I tell Julie we’ll get some food later. Mrs. Ewing used to always say I should smile more because I was so pretty, and she’d use that same singsong Bill style, though, which again, I knew but didn’t really know it meant something extra. I’m smart enough to not tell Julie she should smile now. She’s eight and too hip for that now, yeah?

I’m not sure if I’m making a whole lot of sense to Julie. I’m just so happy to be here with her. Here is the half-finished house. Walls and windows are in. Floors are still just plywood and there’s sawdust and plaster everywhere. We’re in a giant room he’s building above a two-car garage. Twelve-foot-high ceilings with enough angles to get lost in. Our shuffling feet and rustling blankets echo. It’s like we’re the last two people left in the world.

It’s snowing hard outside. It’s too dark and cold in here to do much besides huddle under the blankets, talk, watch, and listen. My arms itch and shake but not because of the cold. Julie is big enough to fit into me like I’m an old rocking chair. I hold her instead of scratching my arms. I hum the family song until I think she’s asleep. But I can’t sleep. Not anymore.

* * *

The wind kicks up and this skeleton house groans and rattles. There’s a rumbling under the howling wind, and it vibrates through my chilled toes. I’m leaning with my back against the wall, arms and legs wrapped in bows around Julie. I tell Julie those aren’t explosions or anything like that, and that sometimes you can get thunder in a nor’easter. I’m talking out of my ass, and it’s so something a mom would say, right?

We get up off the floor. Julie is quicker than me. My bones are fossilized to their rusty joints and I need a smoke real bad again. Maybe I need more. There’s no maybe about it.

Julie stands at a window, nose just about against the glass. Because we’re higher up than the rest of the neighborhood, we can see Gran’s house down the hill and across the way. It looks so small, made of dented cardboard and tape, and it disappears as Julie fogs up the window, putting a ghost on everything outside where it’s all dark and white.

The rumbling is louder, and lower-sounding than thunder. By lower I mean closer to the ground, you know? It doesn’t stop, fade, or become an echo, a memory. It turns our plywood floors into a drumhead. A power saw with its sharp angry teeth shakes and rattles on the contractor’s makeshift worktable in the middle of the room. Then something bounces hard off the window behind us, and Julie screams and dives down into the blankets. I tell her to calm down, to stay there, that I’ll be right back.

I glide through the darkened house. Been in here enough times I’ve already memorized the layout. Practice, baby, practice. Julie’s soccer coach approves of practice, yeah? Straight out of the great room for ten steps, past the dining room, take that second left off the kitchen, no marble countertops yet but dumb-ass left some copper piping out, which I should probably take and sell, then a quick right, eleven stairs down into the basement, left, then through a door into the two-car garage, left again and step out the side door, into the swirling wind that pickpockets my breath.

Four, maybe five inches of snow on the ground, enough to cover the toes of Tony’s boots. My feet are lost in the boots and can’t keep themselves warm. Losers. My shaking hands fish for my cigarette pack. I only have one left, and one