0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

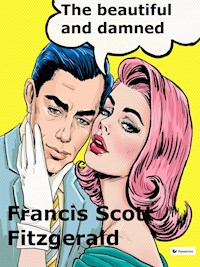

The Beautiful and Damned, first published by Scribner's in 1922, is F. Scott Fitzgerald's second novel. It explores and portrays New York café society and the American Eastern elite during the Jazz Age before and after the Great War in the early 1920s.

As in his other novels, Fitzgerald's characters in this novel are complex, materialistic and experience significant disruptions in respect to classism, marriage, and intimacy . The work generally is considered to be based on Fitzgerald's relationship and marriage with his wife Zelda Fitzgerald.

The author

Francis Scott Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American author of novels and short stories.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Francis Scott Fitzgerald

The sky is the limit

Table of contents

BOOK ONE

I

ANTHONY PATCH

A WORTHY MAN AND HIS GIFTED SON

PAST AND PERSON OF THE HERO

THE REPROACHLESS APARTMENT

NOR DOES HE SPIN

AFTERNOON

THREE MEN

NIGHT

A FLASH-BACK IN PARADISE

II

PORTRAIT OF A SIREN

A LADY’S LEGS

TURBULENCE

THE BEAUTIFUL LADY

DISSATISFACTION

ADMIRATION

III

THE CONNOISSEUR OF KISSES

TWO YOUNG WOMEN

DEPLORABLE END OF THE CHEVALIER O’KEEFE

SIGNLIGHT AND MOONLIGHT

MAGIC

BLACK MAGIC

PANIC

WISDOM

THE INTERVAL

TWO ENCOUNTERS

WEAKNESS

SERENADE

BOOK TWO

I

THE RADIANT HOUR

HEYDAY

THREE DIGRESSIONS

THE DIARY

BREATH OF THE CAVE

MORNING

THE USHERS

ANTHONY

GLORIA

“CON AMORE”

GLORIA AND GENERAL LEE

SENTIMENT

THE GRAY HOUSE

THE SOUL OF GLORIA

THE END OF A CHAPTER

II

SYMPOSIUM

NIETZSCHEAN INCIDENT

THE PRACTICAL MEN

THE TRIUMPH OF LETHARGY

WINTER

DESTINY

THE SINISTER SUMMER

IN DARKNESS

III

THE BROKEN LUTE

RETROSPECT

PANIC

THE APARTMENT

THE KITTEN

THE PASSING OF AN AMERICAN MORALIST

NEXT DAY

THE WINTER OF DISCONTENT

THE BROKEN LUTE

BOOK THREE

I

A MATTER OF CIVILIZATION

DOT

THE MAN-AT-ARMS

AN IMPRESSIVE OCCASION

DEFEAT

THE CATASTROPHE

NIGHTMARE

THE FALSE ARMISTICE

II

A MATTER OF AESTHETICS

THE WILES OF CAPTAIN COLLINS

GALLANTRY

GLORIA ALONE

DISCOMFITURE OF THE GENERALS

ANOTHER WINTER

“ODI PROFANUM VULGUS”

THE MOVIES

THE TEST

III

NO MATTER!

RICHARD CARAMEL

THE BEATING

THE ENCOUNTER

TOGETHER WITH THE SPARROWS

Credits

Francis Scott Fitzgerald

THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED

BOOK ONE

I

ANTHONY PATCH

In 1913, when Anthony Patch was twenty-five, two years were already gone since irony, the Holy Ghost of this later day, had, theoretically at least, descended upon him. Irony was the final polish of the shoe, the ultimate dab of the clothes-brush, a sort of intellectual “There!”— yet at the brink of this story he has as yet gone no further than the conscious stage. As you first see him he wonders frequently whether he is not without honor and slightly mad, a shameful and obscene thinness glistening on the surface of the world like oil on a clean pond, these occasions being varied, of course, with those in which he thinks himself rather an exceptional young man, thoroughly sophisticated, well adjusted to his environment, and somewhat more significant than any one else he knows.

A WORTHY MAN AND HIS GIFTED SON

Anthony drew as much consciousness of social security from being the grandson of Adam J. Patch as he would have had from tracing his line over the sea to the crusaders. This is inevitable; Virginians and Bostonians to the contrary notwithstanding, an aristocracy founded sheerly on money postulates wealth in the particular.

PAST AND PERSON OF THE HERO

At eleven he had a horror of death. Within six impressionable years his parents had died and his grandmother had faded off almost imperceptibly, until, for the first time since her marriage, her person held for one day an unquestioned supremacy over her own drawing room. So to Anthony life was a struggle against death, that waited at every corner. It was as a concession to his hypochondriacal imagination that he formed the habit of reading in bed — it soothed him. He read until he was tired and often fell asleep with the lights still on.

THE REPROACHLESS APARTMENT

Fifth and Sixth Avenues, it seemed to Anthony, were the uprights of a gigantic ladder stretching from Washington Square to Central Park. Coming up-town on top of a bus toward Fifty-second Street invariably gave him the sensation of hoisting himself hand by hand on a series of treacherous rungs, and when the bus jolted to a stop at his own rung he found something akin to relief as he descended the reckless metal steps to the sidewalk.

NOR DOES HE SPIN

The apartment was kept clean by an English servant with the singularly, almost theatrically, appropriate name of Bounds, whose technic was marred only by the fact that he wore a soft collar. Had he been entirely Anthony’s Bounds this defect would have been summarily remedied, but he was also the Bounds of two other gentlemen in the neighborhood. From eight until eleven in the morning he was entirely Anthony’s. He arrived with the mail and cooked breakfast. At nine-thirty he pulled the edge of Anthony’s blanket and spoke a few terse words — Anthony never remembered clearly what they were and rather suspected they were deprecative; then he served breakfast on a card-table in the front room, made the bed and, after asking with some hostility if there was anything else, withdrew.

AFTERNOON

It was October in 1913, midway in a week of pleasant days, with the sunshine loitering in the cross-streets and the atmosphere so languid as to seem weighted with ghostly falling leaves. It was pleasant to sit lazily by the open window finishing a chapter of “Erewhon.” It was pleasant to yawn about five, toss the book on a table, and saunter humming along the hall to his bath.

THREE MEN

At seven Anthony and his friend Maury Noble are sitting at a corner table on the cool roof. Maury Noble is like nothing so much as a large slender and imposing cat. His eyes are narrow and full of incessant, protracted blinks. His hair is smooth and flat, as though it has been licked by a possible — and, if so, Herculean — mother-cat. During Anthony’s time at Harvard he had been considered the most unique figure in his class, the most brilliant, the most original — smart, quiet and among the saved.

NIGHT

Afterward they visited a ticket speculator and, at a price, obtained seats for a new musical comedy called “High Jinks.” In the foyer of the theatre they waited a few moments to see the first-night crowd come in. There were opera cloaks stitched of myriad, many-colored silks and furs; there were jewels dripping from arms and throats and ear-tips of white and rose; there were innumerable broad shimmers down the middles of innumerable silk hats; there were shoes of gold and bronze and red and shining black; there were the high-piled, tight-packed coiffures of many women and the slick, watered hair of well-kept men — most of all there was the ebbing, flowing, chattering, chuckling, foaming, slow-rolling wave effect of this cheerful sea of people as to-night it poured its glittering torrent into the artificial lake of laughter. . . .

A FLASH-BACK IN PARADISE

Beauty, who was born anew every hundred years, sat in a sort of outdoor waiting room through which blew gusts of white wind and occasionally a breathless hurried star. The stars winked at her intimately as they went by and the winds made a soft incessant flurry in her hair. She was incomprehensible, for, in her, soul and spirit were one — the beauty of her body was the essence of her soul. She was that unity sought for by philosophers through many centuries. In this outdoor waiting room of winds and stars she had been sitting for a hundred years, at peace in the contemplation of herself.