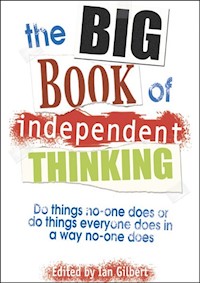

The Big Book of Independent Thinking E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1992 Ian Gilbert, author of the highly acclaimed Essential Motivation in the Classroom founded Independent Thinking Ltd (ITL). His aim was to 'enrich young people's lives by changing the way they think and so to change the world'. He has done this by gathering together a disparate group of associates specialists in the workings of the brain, discipline, emotional intelligence, ICT, motivation, using music in learning, creativity and dealing with the disaffected. ITL achieve their objective by 'doing what no one else does or doing what everyone else does in a way no one else does'. With a chapter from each of the associates plus an introduction and commentary by Ian Gilbert, this is the definitive guide for anyone wishing to understand and use some of the thinking that makes ITL such a unique and successful organisation. If you're looking for a quick 'How to'guide and a series of photocopiable worksheets you can knock out for a last minute PSHE lesson or because the INSET provider you had booked has let you down at the last minute and you're the only member of the middle management team who didn't attend the last planning meeting so you've ended up with the job of stepping in to fill in the gap, then this is the book for you. As befitting a disparate group of people brought together under the banner of Independent Thinking, these chapters are to get you thinking for yourself thinking about what you do, why you do what you do and whether doing it that way is the best thing at all. This book is meant to be dipped into, with not every chapter being relevant for everybody all of the time. Some chapters are written with the classroom practitioner very much in mind, others with the students in mind, other still with an eye on school leaders. That said, there is something here for everyone so we encourage you to dip into it with a highlighter pen in one hand and a notebook in the other to capture the main messages and ideas that resonate with you. So, does the assembly you're about to give, or that lesson on 'forcesyou're about to deliver or that staff meeting you're about to lead or that new intake parents evening you're planning look like everyone else's anywhere else? If so, then what about sitting down with your independent thinking hat on and identifying how you can make it so that we couldn't drop you into a totally different school on the other side of the country without anyone noticing the difference. Have the confidence to be memorable the world of education needs you to be great.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To our wives, partners, husbands, children, colleagues, employers and students who have helped make it possible for us to go out and share with others the ideas and inspirations found in this book

– we thank you.

Acknowledgements

Knowledge used to be like gold. The more you had – and hung on to – the more powerful and useful you were. These days think of it like milk. If you hang on to it, it goes off. In this book, we have built on a great deal of great knowledge – adapted it, played around with it, improved it in places and passed it on and encouraged others to pass it on too before it curdles.

We acknowledge the shoulders of the educational giants we are standing on – people over the centuries who have realised that, when it comes to teaching young people, there must be a better way.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction to Independent Thinking LtdTen Things You Should Know Before You Read This Book

Introducing David KeelingChapter 1 On Love, Laughter and Learning by David Keeling

Introducing Nina JacksonChapter 2 Music and the Mind by Nina Jackson

Introducing Jim RobersonChapter 3 The Disciplined Approach by Jim Roberson

Introducing Matt GrayChapter 4 ‘Lo Mejor es Enemigo de lo Bueno’ by Matt Gray

Introducing Guy ShearerChapter 5 Peek! Copy! Do! The Creative Use of IT in the Classroom by Guy Shearer

Introducing Andrew CurranChapter 6 How The ‘Brian’ Works by Andrew Curran

Introducing Roy LeightonChapter 7 Living a Creative Life by Roy Leighton

Introducing Michael BrearleyChapter 8 Build the Emotionally Intelligent School or The Art of Learned Hope by Michael Brearley

Copyright

Introduction to Independent Thinking Ltd

Independent Thinking Ltd is a unique network of educational innovators and practitioners who work throughout the UK and abroad with children and their teachers and school leaders. It was established in 1993 by Ian Gilbert and delivers in-school training, development, coaching and consultancy as well as producing books, articles, teaching resources and DVDs and hosting public courses.

Ian Gilbert is the founder and managing director of Independent Thinking Ltd. Apart from his speaking engagements in the UK and abroad, he is the author of the bestselling Essential Motivation in the Classroom and Little Owl’s Book of Thinking.

David Keeling is a professional actor, drummer, magician, stand-up comedian and committed educationalist who specialises in bringing the best out of some of the hardest-to-reach children in British schools.

Nina Jackson is an opera-trained music teacher with huge experience working in special needs, music therapy, teacher training and mainstream teaching where her research into music for motivation and learning is achieving national recognition.

Jim Roberson is a former professional American football player from the Bronx who is teaching in a challenging south coast school where his role is the ‘Discipline Coach’. He also runs a unique ‘work appreciation’ programme for disadvantaged young people each summer in a number of authorities.

Matt Gray is a professional theatre director and teacher who is currently working at Carnegie Mellon University in the US. Before that he was a leading trainer at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts as well as directing theatre in London and abroad.

Guy Shearer is the Director of the Learning Discovery Centre in Northampton – a centre working to promote smarter learning that sometimes uses new technologies.

Andrew Curran is a practising paediatric neurologist at Alder Hay Children’s Hospital in Liverpool. He is on the board of the Emotional Intelligence Journal and is leading a number of research projects on the neurological benefits of an education system that teaches – and practises – emotional effectiveness.

Roy Leighton is a lecturer at the European Business School, a coach and trainer to top-level business, author and TV programme maker, his first major series being Confidence Lab on BBC television. Apart from his speaking work for Independent Thinking Ltd, he is also a sought-after consultant across the UK, working with senior management on school change.

Michael Brearley is a former teacher and head-teacher who is now a leading trainer and coach in school leadership, effectiveness and emotional intelligence in the classroom. He has been involved in a number of successful long-term school transformation projects across the UK and written several books and programmes.

Ten Things You Should Know Before You Read This Book

Introducing David Keeling

What’s big and ginger and makes you laugh? For those of you who have never seen David Keeling in action, you will have to put aside the image you have now of a carrot in a hat or Chris Evans’s latest TV programme being taken off the air, and focus instead on the common sense that David dishes out in his chapter.

For over five years, David has worked with young people who were failing – and being failed by – the system and has consistently achieved the seemingly impossible task of helping many of them re-engage with, and refocus on, their success in school and beyond.

His own story is one that many young people can relate to. He is someone who struggled not only with the narrow academic demands of educational success but also with the relevance of school itself, especially secondary school, where he attended a ‘bog-standard comp’ somewhere off the M1 to the west of D. H. Lawrence.

A crucial weapon that he advocates and employs himself to great effect is the use of humour. I have seen him win over large groups of disaffected Year 11s within seconds by his self-deprecating wit and his ability to see it – and tell it – how it is.

He points out how important laughter is for the learning process, something that is backed up by recent research revealed in the journal Scientific American Mind. Psychologist Kristy A. Nielson of Marquette University was testing her subjects for recall by teaching students thirty new words. However, one group was played a humorous video clip half an hour after the learning process. Both groups were then tested for recall one week later. The group that had followed the learning with the laughing showed a 20 per cent better recall rate than the other group.

You could have a 20 per cent increase in your class’s achievements just by using laughter as a learning tool – and now you have the research to back you up when Ofsted come around and accuse you of having ‘too much fun’ in your lessons. In fact, copy the following sentence on to a piece of paper and stick it in your desk drawer for later use:

We are not having fun, Mr Inspector: we are simply using positive emotions to obviate negative reptilian brain responses in order to access the limbic system to optimise dopamine release and facilitate autonomic learning.

Having fun and enjoying yourself is not an optional extra for a human being, whatever the age. A Time magazine feature in February 2005 took a look at a great deal of the research being carried out worldwide on the benefits of happiness, benefits that include reductions in heart disease, pulmonary problems, diabetes, high blood pressure, colds and infections of the upper respiratory tract. Happy people developed 50 per cent more antibodies after a flu vaccination, and, in a longitudinal study of 1,300 men over ten years, there was 50 per cent less heart disease in the optimistic men. Not to mention the fact that, according to gelotologists (no, you look it up), a hundred laughs is the equivalent of a ten-minute row, and laughter actually produces a significant reduction in levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that can actually impede our ability to lay down memories.

Education is too important to be taken seriously. Teaching children how to be happy – especially by modelling it to them – is no happy-clappy desertion of our duties but an important part of teaching them how to have enjoyable, fulfilled and long lives. Indeed, you may have seen articles in the national press about schools that are already starting to teach happiness to students.

How do we get to be happy in the first place? Although some people are ‘born happy’, the ‘plastic’ nature of our brains means that this is no guarantee that they will remain happy. ‘Consistent stress can reduce happiness,’ the Time article points out (although ‘moderate doses’ of negative experiences help us learn how to cope with life’s little knocks and setbacks in a way that helps us bounce back quickly).

Experts suggest that there are three sorts of happiness:

Sensory pleasure. A smile stimulates the opioid system but is it transitory? How many have spent their lives chasing after such shadows?A sense of engagement, of being ‘in the moment’, of ‘flow’.Having meaning in our life.Raise our levels of items 2 and 3 and we raise our happiness levels. Or, in the words of Ruut Veerhoven, professor of happiness at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, ‘Happiness is how much you like the life you’re living.’

Are you teaching children to like the life they’re living and to live a life they’ll like? Do you like the life you’re living? It’s never too late. As Bertolt Brecht said, ‘You can make a fresh start with your dying breath.’

Another neurological benefit from experiencing pleasure in your life is the chemical dopamine, something that David not only taps into in his work but also draws your attention to in his chapter. According to our very own Dr Curran, it’s the ‘ultimate learning neurochemical’ and a key part of the chemistry of memory. A surge of dopamine will help us better remember the fifteen to thirty minutes or so prior to the surge taking place. Perhaps this is what the Marquette University research above was benefiting from. And the adolescent brain is a very dopamine-rich environment. Those young people need dopamine, and lots of it. This explains some of their risk-taking behaviour and their ability to party all night but barely stay awake for your chemistry lesson.

And take heed: if they don’t get the dopamine they need with your help they will get it despite you.

Through the ‘having a laugh’ approach to motivation that David espouses, there are also some very serious and life-changing messages about the need for change – for all of us – why it is necessary and what can so often prevent us from achieving it. If we as adults show resistance to change, what sorts of messages does that portray to young people, people who are setting out into a life where change will be happening for them far faster than it ever happens for us?

And change brings with it the threat of failure. But that’s OK. ‘We’ve got to fail faster to learn quicker to succeed better,’ as the US head of McDonald’s once said. We owe it to our children to embrace change and the effects of it for better or for worse to prepare them halfway adequately for twenty-first-century life.

One final thing. David is an actor by trade and is very much a ‘get up and do’ sort of teacher. So, there are a great many really simple but effective exercises in here that I have seen him use with young people and teachers alike to get them moving, thinking and changing.

So, push back the chairs, loosen your clothing and welcome to The Big Book of Independent Thinking’s very own self-professed Ginger Ninja.

Chapter 1

On Love, Laughter and Learning

David Keeling

Before I leap dramatically into the chapter, I would like to begin by doing this same exercise with you, the reader, right now, to keep you on your toes and to make sure that you are not just flicking through to find the pictures.

It is an exercise that I always do at the beginning of my sessions. I do it because my work within education is usually centred on one word: success. So, I like to check with the group to see how successful the one hour, morning or day will be and what responsibility the group are taking to make sure that it is as successful as it can be.

A great pal of mine and fellow Independent Thinker, Roy Leighton (see Chapter 7), trained in Kabuki theatre in Japan and they use this exercise as a technique for getting into what they call a ‘state of flow’ or a readiness to be absolutely fantastic.

I’d like to put you in this state now by checking three things – your levels of:

Energy; Openness; and Focus.On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is low and 10 is high, what is your level of ‘Energy’ at this moment in time?

I normally get the students to shout their answers out after a count of three, but I suggest you do it in your head so as not to distress those who may be close by.

If you think you are a ‘1’ then please – and I think this is the correct term – ‘be arsed’ to have a go. If you don’t try, how will you ever know? And if you think you’re a ‘10’ try not to go through the roof!

Now do the same for ‘Openness’, by which I mean how open are you to getting involved in your learning, to contributing, to believing that you can change the way you think about yourself, where you are going and what you can achieve?

Finally, do the same for ‘Focus’. What’s your focus like at this moment in time? Is this the fifth time you’ve read this sentence? Are you already wondering what’s for tea tonight or thinking, ‘Does my bum look big in this?’

Many of the kids I come into contact with find it almost impossible to exist in the ‘here and now’, for they are constantly preoccupied with other things that are not related to the task in hand.

I have been to many sessions where some of the audience (normally those sitting at the back) express that they are here against their will and would much rather be somewhere else. The only problem I have with this is that they can’t go anywhere else, but if they continue to focus on what is out of their control then they risk not getting anything valuable done – and what is the point of that?

A Chinese proverb loosely translated puts this argument beautifully: ‘If you have one foot in the past and one foot in the future you will piss on today.’

So I ask you again, what is your focus like at this moment in time? Jot your scores down for Energy, Openness and Focus and we’ll come back to them later.

Now that we’ve worked out what sort of state of readiness you are in for a chapter such as this, let’s get on with the main thrust of what I have to say. All that you will read in this chapter has come together over a ten-year period to challenge the hearts, minds and spirits of kids from all over the country.

When I say kids, I mean either big kids (anyone 16–116), including, parents, teachers, care workers, businessmen and -women), or little kids (anyone aged 6–16), this time including high achievers, the gifted and talented, C/D borderline, EBD (those with emotional and behavioural difficulties) or indeed SBQs (smart but quiet kids, the ones who just seem to get on with it and who are often the most neglected).

All of the work I’m involved in is geared towards improving self-esteem, self-expectation, motivation, confidence, goal setting, visioning skills, success, the brain and how it works and how amazing it is, dealing with change and creativity within the individual. These areas are explored and expressed in a unique way incorporating anything from stories, quotes, jokes, games, improvisation, forum theatre, practical strategies, music, magic and boundless energy.

Ultimately, all of the above has been used to help people become more confident learners and enable them to find ways of embracing change, developing the qualities required for success and finding their own sense of happiness.

Oh, yes, I almost forgot: the majority of the work that I do in schools is with disaffected kids. For eight years, involving thirteen schools, and more than eleven thousand young people, Independent Thinking associate Roy Leighton and I have been running programmes alongside the Raising Standards Partnership in and around Northamptonshire that have the sole purpose of enabling these youngsters to feel ‘capable’ and ‘lovable’ – two words that for us are the real definition of self-esteem.

We have achieved so much within these schools using a technique called ‘forum theatre’. (It’s a bit like role play but less damaging.) The main aim of this theatrical device is to set up a scenario based on the ideas given to us by students involved in the programme. During the scene there will always be a point of conflict between the characters, which needs to be addressed by the members of the audience, who have now taken the role of directors. It is their job to stop the action whenever they feel that the characters are doing something wrong, e.g. being disrespectful, arguing, intimidating someone or being ridiculous (this is usually my job).

At this point the directors have the power to give advice to the actors on what they could be doing to improve the scene and generate a more positive and beneficial conclusion. The scene can then be rerun as many times as it takes until the best possible outcome is achieved.

Where this device has really come into its own is when the kids decide that they no longer want to be spectators and instead become ‘spect-actors’. In this role, the kids get the opportunity to replace the actors and lead from the front in terms of resolving the onstage conflict. This allows the students, within a safe environment, the chance to rehearse their successes. There are no right or wrongs: there is just participation and a desire to transform the action into a more positive direction.

For the kids I have worked with on these programmes, this experience has helped no end in the building of confidence and an openness to look at things differently and to try many ways to create successes. It is through my experiences here and also as an associate of Independent Thinking for over five years working the length and breadth of the country that I feel ably qualified to give advice and suggestions to you in your work with disaffected young people.

My work for Independent Thinking has taken me to some of the most glamorous and exotic places that England has to offer, from Bolton and Stockport to Middlesbrough and Wigan; but, whatever the brief, the outcome and the feedback is always the same. People are genuinely enthused, empowered, excited and enlightened by the information, ideas and theories that they are discovering during these sessions, and there is a huge desire to find out more and at least attempt to do something with this newfound knowledge.

It was my intention, when I started work in education, to ‘put a bit back’ as they say – and to generate some extra income! It is now a passion to create unique experiences and to enthuse young people regarding the many possibilities that taking control over their life can offer, and to encourage people to think, feel and act in order to create a life they want and dream of, rather than a life that was forced upon them or that was left to chance. It is my aim within this chapter to share with you some of my educational experiences and to provide you with some practical strategies that I hope will support you in your work with young people.

All of this aside, it has also been bloody good fun!

I’ve made many friends and I have probably learned more myself than anybody I’ve worked with because, after all, the biggest learner in the classroom should be the teacher – am I right or am I right?

Before I take you through some of the strategies and techniques that I have utilised in my work over the years, let me share with you a couple of thoughts from two heroes of mine (although I know which one I would rather have on my side in a fight):

All great acts of genius began with the same statement, let us not be constrained by our present reality.

– Leonardo da Vinci

Let no way be the way. Let no limitation be limitation.

– Bruce Lee

But less about them and more about me. Let me introduce myself properly. My name is Keeling, David Keeling, or the Ginger Ninja – or, to the thousands of young people I have worked with, the Ginger Man. Not especially creative, or indeed easy to put on the front of my costume, but it suits me and I like it!

Let me give you a bit of my background. I was born in Sheffield in 1973 and was schooled in Nottinghamshire (Dayncourt Comprehensive). I have six GCSEs (failed maths and physics), two and a half A-levels and a diploma in acting from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. It is important to point out that none of the above has ever had any bearing, qualifications-wise, on what I do now as a profession.

On the other hand, my attitude towards myself, the people around me and the environment that I find myself in, most certainly has. I work all over the country and talk to a lot of people about their school experiences, and I never cease to be amazed at how similar their experiences are to mine. At infant and junior school I was having a whale of a time, every day playing with Plasticine and drinking free milk. Occasionally, I had to do PE in my pants and vest, but I’ve had the therapy and I’m feeling much better for it. I don’t know about you, but I found that my polyester two-piece chafed a bit. Especially when I was exiting from a forward roll.

It was a fun-filled creative time that lulled me into a false sense of security with regard to my future educational experiences, because what happened next was secondary school!

When I arrived on my first day, the backside fell out of my universe. Gone was the fun, creative, milk-drinking gymnastics of my primary years, replaced by desks, chalk and talk and textbook after textbook after textbook. For me the creativity, the imagination and the spontaneity had gone and in its place was boredom. Secondary school became, in my experience, a five-year exercise in wasting time. I actually learned more when I left school (not an uncommon event in my experience).

Luckily, three things got me through my comprehensive school experience:

a good sense of humour; the ability to get on with people; and a vision.1. A good sense of humour

Being ginger and chubby at comprehensive school is not a good combination. Fortunately, I’ve since blossomed into a beautiful swan. A ginger swan, I know. Life can be hard enough, so we should be encouraged to have more fun in everything we do.

Andrew Curran, consultant paediatric neurologist and fellow Independent Thinking associate (see Chapter 6), says quite clearly, if not a little ungrammatically, ‘If your heart’s not engaged then your head don’t work.’ So many of the disaffected kids I spend time with are suffering from this dilemma. They feel low or angry within themselves and thus become either reactive or switched off. This disengages the brain and leaves them with a strong sense of feeling incapable and stupid.

If anyone in your life has ever suggested, hinted or quite blatantly said that you are stupid or incapable, then they are wrong and I will willingly pay them a visit to explain why!

Never underestimate anyone – it is the most dangerous form of arrogance.

– Anon

Unfortunately, many of the kids I’ve seen, for whatever reasons, have spent a good deal of their lives being told that they are thick, stupid and useless and will never amount to anything by the very people they trust and look up to the most: parents, teachers and some friends. This can have a massive impact on a youngster’s expectations, self-esteem and perception of what they can achieve with their lives.

The work I do is aiming to create a safe environment for these young people to rediscover their childlike curiosity for learning and to begin the rebuilding of their confidence and expectation of themselves. A good sense of humour and an ability to find fun in learning are, therefore, vital.

We know, scientifically, that if you’re having a good time then endorphins, which are chemicals that occur naturally in our bodies, are released to create even greater feelings of happiness and euphoria. Related to that, dopamine is a chemical that is released when you have either been given or are expecting to receive a reward.

According to Dr Curran, dopamine is the number-one, learning-related, memory-boosting neurochemical, and it is therefore essential that we encourage teachers at every opportunity to use fun and creative teaching methods in order to bring about the release of these chemicals within the children and within themselves. The kids can then begin the process of feeling good about themselves and engage fully in the learning arena.

It should, therefore, be the responsibility of every teacher and pupil to ask themselves, frequently, ‘Am I having fun?’ And, if not, ‘Why not?’ and ‘What am I doing about it?’ School should be the best party in town, or, as Socrates once said, education should be a ‘festival for the mind’.

2. The ability to get on with people

Some would say that I have strong interpersonal intelligence. I strongly believe that education, first and foremost, is about building relationships. If there is a teacher or a pupil whom you do not get on with, what do you think the chances are of any learning taking place when both of you are in a room together? None, because, if your heart’s not in it, if you do not care for, or respect, the teacher and hate the lesson, then there will be no emotional investment in time or energy.

If you have a situation like this, then my best advice is to be the adult in the relationship and begin to take steps to sort it out, because, while it’s an issue, that issue will always be a block to the learning that could take place. The only person who really loses out in a situation such as this is the pupil. It’s their education and their opportunities that will ultimately suffer.

3. The Ginger Boy had a vision!

I knew what I wanted to do. Unfortunately, my life as a lap dancer did not work out, but I fell into acting and I am much happier for it.

I had a clear idea of where I wanted to be when I was 21 and I was strong-willed enough and determined, even at the tender age of ten, not to let anything or anyone, especially myself, prevent me from achieving my goal of being an actor. By the way, if you or someone you know is thinking of entering this profession then my advice to you would be this: make sure there is something else you can do, otherwise you will spend most of your waking life sitting by a phone waiting for something to happen; or you can do what I did, which is to get out into the world and make something happen using all the skills that you possess.

From the frequent chats that I have had with students over the years, it has become clear that, for a large number of them, school (in terms of work that is expected of you) can be a very frustrating place to be, especially for those students who didn’t really have a clear idea of what they wished to do as a career.

Imagine that every day you are loaded down with work and you don’t really know to what end. If students have no idea what they would like to do as a job, then I will ask them if there is a specific area that they would like to work in, such as sport, media or the forces. If they can’t answer that, then I ask them how they would like to feel in ten years’ time: happy, confident and relaxed, or stressed out, poor and unhappy.

I am pleased to report that everyone would like to attain the former three descriptions (well, everyone except the class comedian). The most frequent comment I hear coming from young people is, ‘What’s the point?’ This is why having a vision early on (even if it changes) is vital in motivating a student to push forward and strive to achieve their goals.

As an exercise in visioning, I ask students where they see themselves in ten years’ time. A lot of them have no idea whatsoever (which may come as no surprise), but this can put a huge spanner in the works with regard to their seeing the clear relevance of what they are doing on a daily basis and the impact it will have on where they’ll end up.

The work I do is about breaking the habits and beliefs that a lot of these kids have formed about themselves and now feel are set and unchangeable. I encourage them to think that, every moment of every day, they have a choice either to do what they always do or to choose to do something different. It is by choosing to do something new that we grow and change the most, and this is the hardest shift a disaffected child will have to make if they really want to prove themselves – and everybody else – wrong.

As Stephen Covey, author of the international bestselling book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, says, ‘Begin with the end in mind.’ If you know what you want, it is so much easier to put all the wheels in motion to get it.

Now, do you remember your scores for Energy, Openness and Focus from the beginning of the chapter? Well, I have used this exercise hundreds of times and very rarely have the scores been high. Normally, they are very similar to this: Energy 5, Openness 6, Focus 5. That adds up to 16 out of a possible 30.

I point out at this juncture that, as a group, we have worked out very quickly that we have a 53.33 per cent chance of getting something positive from whatever we are doing. In other words, just over half a chance. But is that really good enough?

At some point, most of us get caught up in the daily grind of work, school or parenthood and find that we tend to exist on a 5:5:5. This means that we’d love to have more energy but the work is piling up; I had a late night last night and I really can’t be bothered. We would love to be more open but to be open requires the facility to deal with change and that in itself requires effort, and, if we have low energy, then openness is not going happen. We would love to be more focused but we are genuinely worried about what we are having for tea tonight and that our bum really does look big in this!

And existing on a 5:5:5 means we’re not really having a lot of fun. We are unlikely to remember what it is we are doing and we are very unlikely to want to repeat the experience day after day. For most of the kids I work with, this is school (actually for a lot of the teachers I work with, this is school too).

Often, I ask if anyone in the room has had a 10:10:10 experience, that’s 10 Energy, 10 Openness and 10 Focus. I ask them to keep it clean but I’d like to know! I remember one teacher, he was an old boy sitting at the back of an INSET day, who told me his 10:10:10 experience had happened the first time he flew solo in an aeroplane. I asked him many questions, some apparently more odd than the others. For instance, what was the weather like? Who was he with at the time? And what was he wearing?

He answered them all with aplomb and in so much detail that everyone in the room assumed that this experience was a very recent one. It had actually taken place forty years before, yet he remembered it as if it had been the previous day.

When we have 10:10:10 experiences, we are not only having fun, but remember most of what we are doing in great detail and are very likely to want to repeat the experience, or at least a sense of it, again and again. Energy, openness and focus as an exercise enables the youngsters to take responsibility for their learning and to make everyday things we are doing more memorable – for, as we know, memory is linked to emotion in the brain.

That is why we always remember our first kiss or getting punched and for a lot of young men this happens at the same time! It is not rocket science: if we are coming into an environment without Energy, Openness or Focus then can we really expect to learn anything? If we push to create more 10:10:10 experiences and reach that state called flow, then great and memorable things will happen.

Think of an experience, that you have had, where everything seemed to fall into place and you were ‘in the zone’ or experiencing flow. I bet you the price of a pint you can remember it in great detail, down to even the smells and sounds. I also believe that, if given the chance, you would love to have a repeat of the experience or one like it as often as possible.

This exercise is a great one to use at the beginning of a lesson because it’s quick, it encourages audience participation and it involves a lot of shouting! It’s always handy to have something for students to do as soon as they enter a classroom, or they will find something to do, e.g. destroy furniture or encourage supply staff to leave the room via a window.

Energy, Openness and Focus also constitutes a brilliant way to start your lesson. For instance, if one day your classroom results read Energy 2, Openness 7, Focus 6, then it’s quite clear that the first thing you must do is raise the energy by playing a quick game or, failing that, hand out the Red Bull and go for a six-mile run!

Creating a common language and getting the kids to focus on what it is that they are bringing to each session is the first step towards establishing a clear structure and consistent approach to the way a session will run. In my experience with groups of disaffected youngsters, it is exactly this that needs to be laid down, and adhered to, if you ever want learning to take place.

At the outset of a session with young people, I make it quite clear that I work only with geniuses. This remark is normally met with much hilarity and scoffing, as if to suggest I’ll be lucky if there’s one in the room. But I was once told that expectation is everything, that everyone is born with the potential to be a genius, but that the world spends the first seven years ‘de-geniusing’ them.

I believe that everyone I work with is a genius in their own right and that there is plenty of evidence to back it up (see all the other chapters in this book!). It is my request to you that, for the rest of this chapter, you think, feel and respond as though your genius had suddenly been unleashed. However, if this proves too much, then just grin and nod knowingly every time I make a good point that you agree with.

I am requested to work with disaffected Year 11s all over the country – mainly to give them one last motivational boot up the backside so that the school can reach its GCSE targets (although I also do INSETs, which work the other way round).

Let me get one thing straight right now: I don’t really care about GCSE results. This is mainly because, five years after leaving school, these results will be out of date. So surely there has to be something else. And I’m a great believer that attitude will determine altitude. If you genuinely care about yourself and where you are going, things such as GCSE results will come as a matter of course.

Look around you: the majority of young people who are failing their exams lack the confidence to do what is right for themselves, or don’t see the relevance of what it is that they are doing, or have no idea what they want to do or achieve in life and have a bad attitude towards themselves and the people around them.

My aim is to help these kids raise their expectations, dare to dream, see the relevance of school life, begin to develop self-respect and set themselves targets to attain. Once this has been achieved, the GCSEs will become one step to another phase of our life rather than the be-all and end-all of our existence, which at times they can seem to be.

After all, millions of years of neurological evolution have not geared all of us just to pass an exam. There has to be more to life than just a piece of paper with letters on it. Although the bits of paper have an importance, I feel that we should first concentrate on the individual to build on and strengthen their inherent qualities in order to provide a sturdy platform from which they can leap into their school life and all it has to offer. Everybody I’ve ever met through my work wants to be happy and successful because that is what life’s all about, isn’t it?

When I use the word success, I’m aware that it means different things to different people. To me it is not just about having money or celebrity, but being happy and fulfilled, establishing strong loving relationships, embracing change and feeling as if you’ve lived life to the maximum. You can then wake up every day, looking forward and smiling at the face that looks back at you from the mirror.

Once we have established high expectations and a sense of willingness to change with a group of young people, I then always ask the following question: ‘On a scale of one to ten, with one “low” and ten “high”, how successful do you want to be?’ I normally brace myself as I’m pinned to the nearest wall by the cacophony of noise created by a room full of young ’uns screaming, ‘Ten!’

Everybody wants, and dreams of, success. Some are happier to tell you than others, so why is it that not everyone goes on to achieve it?

Lack of confidence, ‘can’t be bothered’ and social circumstances are some of the replies I’ve heard. Roy Leighton and I have been looking at the relationship between people and success and, over the years, have come up with and developed six key qualities that everyone needs to have and develop in order to be successful. For this we created the mnemonic ‘BECOME’:

BraveryEnergyCreativityOpennessMotivationEsteem

My belief is that not everyone achieves the success they desire because these areas are underdeveloped, sometimes severely so.

You may have all the qualifications in the world, but, if you are not brave enough to challenge yourself often, if you lack energy, if you lack the ability to come up with new ideas, if you are closed-minded to new or alternative methods of doing things, if you have no motivation and your confidence is rock bottom, then you may find yourself in the unenviable position of being highly qualified but unemployable.

Think of any job, e.g. a firefighter, sportsperson or actor. To be successful and happy within any of these professions will require you to challenge yourself in each area of BECOME on a regular basis. Where, then, in schools is the space or time put aside so that these qualities can be explored, learned and developed?

Once again, give yourself a score from 1 to 10 for each of the qualities of BECOME. On a daily basis, how brave are you? How energetic? And so on. Which are the areas where you scored highest? Which are the areas where you scored lowest? And what can you do to increase your score in each of these areas? After all, challenging ourselves little and often is one of the best ways to increase our potential and confidently approach change. The way that changes are dealt with can bring about the biggest challenges that face young people, especially boys.

I use BECOME as a creative tool to enlighten and engage young people and help them understand that their attitude to themselves and the things they do has a huge influence over how fun and exciting their educational experience can be.

In working with the students on BECOME, it is vital that, for each of these important qualities, there is a tangible experience that will stimulate their thoughts, feelings and actions. To help with this, we have, over the years, created a large variety of games and exercises to raise the young people’s awareness and ability in each of the areas that BECOME promotes. So here, for your delectation, is a taster of the kinds of exercises and games that I use to challenge the kids in each of the areas.

Bravery

Dictionary definition – ‘courage in the face of danger or difficulty’

Everyone in the session will require one plain sheet of paper (the bigger the better). Down the middle they should draw a line from top to bottom. On the left-hand side at the top, the students must put a plus (+) sign and on the right-hand side at the top they must place a minus (–) sign. For fun they may wish to draw a picture of themselves in the middle of the sheet.

The paper should now look like this:

The students should then be given at least five minutes to write down on the plus side a list of all their strengths, the things that they are good at and what makes them unique. The kinds of answers I’ve had in the past have included ‘funny’, ‘kind’, ‘talkative’, ‘history’, ‘running’, ‘eating’ and ‘good in bed’ (I think this was referring to sleep!). They can put down whatever they want as long as it is positive and makes them feel good.

Encourage them to make the list as long as possible. In my experience, the majority will find this first exercise difficult. For instance, a lot of students feel that talking is not a strength. As a nation, we are not encouraged to celebrate the things that we are great at. But, with some gentle coaxing and a few ideas, they’ll soon get going.

It is imperative that young people recognise and are recognised for these strengths, so they can then begin to use them as a foundation, which can become a springboard to all kinds of new learning situations.

A good idea, once this list has been compiled, is to get each of the kids to read out their list and then to pick the strength that they feel is their greatest. This all helps to reinforce in the individual that everyone has different abilities and that this is the starting point for their confidence and self-esteem to grow.

Now they can move to the right-hand side of the page and make a list of all the things that they feel are getting in the way of their success, happiness and ability to develop. Some of the classic answers I have seen on lists have been, ‘easily distracted’, ‘can’t be arsed’, ‘never contribute’, ‘don’t like the teachers’ and ‘don’t do the work that’s set’. It doesn’t mean they are devoid of the abilities listed: it means that these areas will require more time and focus to get things back on track.

To address the aspects on the negative half of the paper it makes sense to draw on the strengths listed on the other half. For example, if you are easily distracted but a good talker, then use this skill to your advantage. Talk it through with your friends and explain that during a particular lesson you would like to focus much more than normal and would appreciate some time on your own. If they are your true friends then of course they’ll understand.

The purpose of this exercise is informally to create some time to reflect on what it is we are already good at and on the things we need to improve on in order to become even better. If the groups are working well, you may want to pass the sheets around and have the students’ friends add at least one quality to the list.

Everyone needs a starting point and everyone requires the bravery to begin at this point in order to move forward.

This exercise can be as long or as short as you wish it to be, but I recommend it be no shorter than fifteen minutes, since this will create the freedom for time and thought to take place and the lists to be a mile long.

Energy

Dictionary definition – ‘intensity or vitality of action or expression’

Stop/Go is possibly my favourite game for two reasons:

I don’t have to do it because I’m leading it; and it’s hilarious watching everybody desperately trying to wrestle with years of fixed patterns of thinking.The other great thing about this game is that you can play it anywhere with any number of people (my record so far is about five hundred!). This is how it goes.

You ask everybody in the room to stand up and explain that you are going to play a game that will require them to do exactly as you say but with no talking. You will be shouting out some very simple instructions that they will need to listen to. When you say ‘Go’ you would like them just to walk on the spot briskly and with enthusiasm. When you shout ‘Stop’ you would like them to stop still straight away.

At this point, as a warm up, you can shout ‘Stop’ or ‘Go’ as many times as you want and for varying lengths of time and in any order, just to make sure that the group are concentrating.

You can now explain that, since they all found that so easy, you are going to change it around a bit. From now on when you say ‘Stop’ it means ‘Go’ and when you say ‘Go’ it means ‘Stop’. The faster you say this, the funnier and more confusing it is.

Check for understanding. If there isn’t any, say the sentence again but even more quickly.

You then begin once more and this time you can have lots of fun watching the total confusion, frustration and hysteria taking over the room as the people struggle with this simple reversal of orders.

Now it’s time to announce some more instructions. From now on when you say ‘Clap’ you would like everyone in the room to clap once and together (you may wish to practise this: the older they are the more this action eludes them!) and when you say ‘Jump’ you would like them to do a little jump, nothing ridiculous, just enough to see the room move. Practise this a few times and, quick as a flash, at least 99 per cent of the room will have forgotten the Stop/Go instruction and the fact that it’s still reversed. Drop this back in and you’ll catch the whole room out. Continue with Stop/Go and Clap/Jump for a minute or so then get everyone to stop by saying ‘Go’!

Confused yet? It gets worse, but it’s much easier to play than to explain.

From now on when you say ‘Go’ you mean ‘Stop’ and when you say ‘Stop’ you mean ‘Go’; when you say ‘Clap’ you mean ‘Jump’ and when you say ‘Jump’ you mean ‘Clap’. This announcement will usually be met with looks of bewilderment and utter confusion mixed in with screams and much laughter.

You can see the pattern forming. As the game leader, you’ll really enjoy adding to the mêlée by setting up patterns and then changing them using your voice, intonation and dramatic pauses.

To cause even more confusion create lots more instructions to follow, such as ‘Sit Down’/‘Stand Up’ or ‘Left Arm’/‘Right Arm’. The more the merrier.

The main purpose of this game is to have fun and raise the level of energy within the group along with improving – or showing problems with – listening skills. It also encourages the use of whole-brain thinking (using the left and right hemispheres at the same time) while, at the same time, demonstrating how fixed our thinking can be and how this limits our ability to be open to new ideas and new ways of thinking.

Creativity

Dictionary definition – ‘originality of thought, showing imagination, sophisticated bending of the rules or conventions’

Whether you consider yourself to be arty-farty or not, creativity is naturally present in all of us. It is my job to assist the students in uncovering and exercising what is already there. Unfortunately, a lot us, due often to our educational experiences, have allowed this essential tool to get lost at the back of our mind kits.

Get your students to pair up or in the case of odd numbers threes will do. Each pair requires one pen and one large sheet of plain white paper. The pen is to be held over the paper by both (or all three) students using one hand each. (By the way, this exercise works just as well with grown-ups.)

You then explain that they now have one minute to draw a house. When the minute is up ask them to place their pens down. I guarantee that 99 per cent of the pictures drawn will look like this:

If they are feeling particularly artistic you may also encounter a variety of optional extras such as smoke coming out of the chimney, a wibbly-wobbly path, a garage and maybe even some cartoon planting. Basically, you will see a house that you would expect to have been drawn by a six-year-old.

Ask the group why they seem to have drawn the same house? Have they ever seen a house like that? Explain that the brief was to draw a house. The students could have drawn anything they wanted – no restraints, just that it’s ‘a house’. Tell them that they are going to do the exercise again but this time they can have a couple of minutes to discuss and plan their dream house. It can be any size or shape and anywhere in the world; it can be made of chocolate or, as one boy suggested, a pub floating above Newcastle United’s football ground. It can be on the moon, or underwater, one room or a thousand rooms. It simply doesn’t matter.

So, as before in their pairs, they have a minute to draw this dream house. You may wish to give them a little longer if you feel it’s necessary or need to pop out to make a phone call. When this time is up, you will see a huge difference in the drawings because this time they have used their imagination, they have dared to dream and the results are amazing. Each drawing is unique: mansions, islands, tree houses, fish, biscuits – you name it and the kid wants to live in it.

Take time to go around all the pictures. The kids may even want to talk you through them. Ask them which house they enjoyed drawing the more (it’s always the latter one).

This exercise is so effective in not only showing what happens to our brain when we are put under the pressure of time but also how we resort to simple patterns of behaviour without being actively encouraged to break the perceived rules and be creative. Our brain shuts down and we revert to the first thing that comes into our head or will get us through whatever has been set, e.g. a six-year-old’s version of a house.

The difference between the two drawings was a couple of minutes. Imagine that we gave the students more time to dream and be creative, thus enabling their imaginations to wander and seek out new ways to do things rather than conforming to what everybody else does.