7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

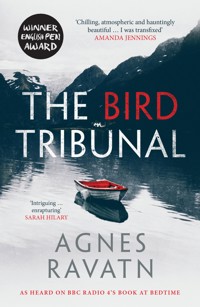

When a disgraced TV presenter takes up the role of housekeeper on an isolated Norwegian fjord, she develops a chilling, obsessive relationship with her employer … an award-winning, simply stunning debut psychological thriller from one of Norway's finest writers. ***As heard on BBC Books at Bedtime*** ***WINNER of the English PEN Translation Award*** ***Shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award*** ***Shortlisted for the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year*** 'An unrelenting atmosphere of doom fails to prepare readers for the surprising resolution' Publishers Weekly 'Unfolds in an austere style that perfectly captures the bleakly beautiful landscape of Norway's far north' Irish Times _________________ Two people in exile. Two secrets. As the past tightens its grip, there may be no escape… TV presenter Allis Hagtorn leaves her partner and her job to take voluntary exile in a remote house on an isolated fjord. But her new job as housekeeper and gardener is not all that it seems, and her silent, surly employer, 44-year-old Sigurd Bagge, is not the old man she expected. As they await the return of his wife from her travels, their silent, uneasy encounters develop into a chilling, obsessive relationship, and it becomes clear that atonement for past sins may not be enough… Haunting, consuming and powerful, The Bird Tribunal is a taut, exquisitely written psychological thriller that builds to a shocking, dramatic crescendo that will leave you breathless. _________________ 'Reminiscent of Patricia Highsmith – and I can't offer higher praise than that – Agnes Ravatn is an author to watch' Philip Ardagh 'A tense and riveting read' Financial Times 'Crackling, fraught and hugely compulsive slice of Nordic Noir … tremendously impressive' Big Issue 'Beautifully done … dark, psychologically tense and packed full of emotion both overt or deliberately disguised' Raven Crime Reads 'Ravatn creates a creeping sense of unease, elegantly bringing the peace and menace of the setting to vivid life. The isolated house on the fjord is a character-like shadow in this tale of obsessions. This is domestic suspense with a twist – creepy and wonderful' New Books Magazine 'The Bird Tribunal offers an incredible richness of themes … The atonement for the past sins and the titular bird tribunal carry powerful messages, as well as questions of morality and humanity…' Crime Review 'The Bird Tribunal is suffused with dark imagery from the ancient Eddas, creating a foreboding atmosphere that gets under the skin and stays there. Like a lunar eclipse, each revelation is another form of darkness' Crime Fiction Lover 'Chilling, atmospheric and hauntingly beautiful … I was transfixed' Amanda Jennings 'Intriguing … enrapturing' Sarah Hilary 'A masterclass in suspense and delayed terror, reading it felt like I was driving at top speed towards a cliff edge - and not once did I want to take my foot off the pedal' Rod Reynolds 'A beautifully written story set in a captivating landscape … it keeps you turning the pages' Sarah Ward

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 292

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

The Bird Tribunal

Agnes Ravatn

Translated by Rosie Hedger

Contents

The Bird Tribunal

My pulse raced as I traipsed through the silent forest. The occasional screech of a bird, and, other than that, only naked, grey deciduous trees, spindly young saplings and the odd blue-green sprig of juniper in the muted April sunlight. Where the narrow path rounded a boulder, an overgrown alley of straight, white birch trees came into view, each with a knot of branches protruding from the top like the tangled beginnings of birds’ nests. At the end of the alley of trees was a faded-white picket fence with a gate. Beyond the gate was the house, a small, old-fashioned wooden villa with a traditional slate roof.

Silently I closed the gate behind me and walked towards the house, making my way up the few steps to the door. I knocked, but nobody opened; my heart sank. I placed my bag on the porch steps and walked back down them, then followed the stone slabs that formed a pathway around the house.

At the front of the property, the landscape opened up. Violet mountains with a scattering of snow on their peaks lay across the fjord. Dense undergrowth surrounded the property on both sides.

He was standing at the bottom of the garden by a few slender trees, a long back in a dark-blue woollen jumper. He jumped when I called out to greet him, then turned around, lifted a hand and trudged in a pair of heavy boots across the yellow-grey ground towards me. I took a deep breath. The face and body of a man somewhere in his forties, a man who didn’t look as if he were in the slightest need of nursing. I disguised my surprise with a smile and took a few steps towards him. He was dark and stocky. He didn’t look me in the eye but instead stared straight past me as he offered me an outstretched hand.

Sigurd Bagge.

Allis Hagtorn, I said, lightly squeezing his large hand. Nothing in his expression suggested that he recognised me. Perhaps he was just a good actor.

Where are your bags?

Around the back.

The garden behind him was a grey winter tragedy of dead shrubbery, sodden straw and tangled rose thickets. When spring arrived, as it soon would, the garden would become a jungle. He caught my worried expression.

Yes. Lots to be taken care of.

I smiled, nodded.

The garden is my wife’s domain. You can see why I need somebody to help out with it while she’s away.

I followed him around the house. He picked up my bags, one in each hand, then stepped into the hallway.

He showed me up to my room, marching up the old staircase. It was simply furnished with a narrow bed, a chest of drawers and a desk. It smelled clean. The bed had been made up with floral sheets.

Nice room.

He turned without replying, bowing his head and stepping out of the room, then nodded towards my bathroom and walked down the stairs, without indicating what was through the other door on the landing.

I followed close behind him, out of the house and around the corner, across the garden and over to the small tool shed. The wooden door creaked as he opened it and pointed at the wall: rake, shovel, crowbar.

For the longer grass you’ll need the scythe, if you know how to use it.

I nodded, swallowing.

You’ll find most of what you need in here. Garden shears and the like, he continued. It would be good if you could neaten up the hedge. Tell me if there’s anything else you need and I’ll see that you get the money to buy it.

He didn’t seem particularly bothered about making eye contact with me as he spoke. I was the help; it was important to establish a certain distance from the outset.

Were there many responses to your advertisement? I asked, the question slipping out.

He cast me a fleeting glance from under the dark hair that fell over his forehead.

Quite a few.

His arrogance seemed put on. But I kept my thoughts to myself: I was his property now – he could do as he liked.

We continued making our way around the house and down into the garden, past the berries and fruit trees by the dry stone wall. The air was crisp and bracing, infused with the scent of damp earth and dead grass. He straddled a low, wrought-iron gate and turned back to look at me.

Rusted shut, he said, maybe you can do something about it.

I stepped over the gate and followed him. Steep stone steps led from the corner of the garden down to the fjord. I counted the steps on my way down: one hundred exactly. We arrived at a small, stone jetty with a run-down boathouse and a boat landing to its right. The rock walls of the fjord formed a semicircle around us, shielding the jetty from view on both sides. It reminded me of where I had first learned to swim almost thirty years before, near my parents’ friends’ summer house on a family holiday.

It’s so beautiful out here.

I’m thinking about knocking down the boathouse one of these days, he said, facing away from me. The breeze from the fjord ruffled his hair.

Do you have a boat?

No, he replied, curtly. Well. There’s not much for you to be getting on with down here. But now you’ve seen it, in any case.

He turned around and started making his way back up the steps.

His bedroom was on the ground floor. He motioned towards the closed door, just past the kitchen and living room and presumably facing out onto the garden. He accessed his workroom through his bedroom, he told me.

I spend most of my time in there. You won’t see much of me, and I’d like as few interruptions as possible.

I gave one deliberate nod, as if to demonstrate that I grasped the significance of his instructions.

I don’t have a car, unfortunately, but there’s a bicycle with saddle-bags. The shop is two kilometres north, just along the main road. I’d like breakfast at eight o’clock: two hard-boiled eggs, pickled herring, two slices of dark rye bread and black coffee, he quickly listed.

The weekends are essentially yours to do as you please, but if you’re around then you can serve breakfast an hour later than usual. At one o’clock I have a light lunch. Dinner is at six, followed by coffee and brandy.

After reeling off his requirements he disappeared into his workroom, and I was left in peace to acquaint myself with the kitchen. Most of the utensils were well used but still in good shape. I opened drawers and cupboard doors, trying to make as little noise as possible all the while. In the fridge I found the cod fillet that we were to share for dinner that evening.

The tablecloths lay folded in the bottom kitchen drawer, I picked one out and smoothed it over the kitchen table before setting two places as quietly as possible.

At six o’clock on the dot he emerged from his bedroom, pulled out a chair and took a seat at the head of the table. He waited. I placed the dish containing the fish in the middle of the table, then put the bowl of potatoes in front of him. I pulled out my chair and was about to sit down when he halted me with an abrupt wave.

No. You eat afterwards. He stared straight ahead, making no eye contact. My mistake. Perhaps I wasn’t clear about that fact.

I felt a lump form in my throat, picked up my plate and quickly moved it over to the kitchen worktop without uttering a word, a tall, miserable wretch, my head bowed.

I filled the sink with water and washed the saucepan and spoons as he ate. He sat straight-backed, eating without a sound, never once glancing up. Fumbling slightly, I set the coffee to brew, found the brandy in the glass cabinet behind him and, once he had put down his cutlery, cleared the table. I poured coffee in a cup and brandy in a delicate glass, then placed both on a tray and picked it up with shaking hands, clattering in his direction.

When he stood up afterwards, thanked me brusquely for the meal and returned to his workroom, I took my plate to the table and ate my own lukewarm portion, pouring the half-melted butter over the remaining potatoes. I finished the remainder of the washing up, wiped the table and worktop and headed up to my room. I unpacked all of my things and placed the clothes, socks and underwear in the chest of drawers, the books in a pile on the desk.

I made sure my mobile phone was switched off before putting it away inside the desk drawer. I wouldn’t be switching it on again any time soon, not unless there was an emergency. I sat there, perfectly still and silent, afraid to make a sound. I could hear nothing from the floor below my own. Eventually I made my way to the bathroom before turning in for the night.

The blade on the scythe must have been blunt. I cursed the drooping stalks of wet, yellow grass that seemed to escape their fate, regardless of how hard and fast I brandished the blade. It was overcast, the air humid. He had gone into his workroom straight after breakfast. On my way out I had caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror. I realised that I looked as if I were wearing a costume. I was dressed in an old pair of trousers I’d worn painting Mum and Dad’s house one summer; that must have been fifteen years ago now. I’d found them in a cupboard at home just a few evenings ago when packing to come here, along with a paint-splattered shirt. My parents had bid me a relieved farewell as I had left to catch the bus the following morning.

I started to feel my efforts in my back. Sweat beneath my shirt. Tiny insects buzzing all around me, landing in my hair, on my forehead, itching. I was constantly having to stop what I was doing to take off my gloves and scratch my face. The long, golden wisps of straw almost seemed to mock me as they swayed gently in the light breeze. I continued to swing the blade with all my might.

I’d try the rake if I were you.

I spun around to find Bagge standing behind me. I must have looked deranged, spinning around red-faced and decked out in fifteen-year-old rags. My fringe was clinging to my face. Without thinking, I swept it aside with my hand and felt the earth from the gloves smear across my forehead.

The scythe’s no good when the grass is wet.

No. I tried my best to muster a smile, resigned in the face of my own stupidity.

And don’t forget lunch, he said, lightly tapping his wrist to remind me of the time. He turned around and walked away. I quickly glanced up at the house, the window to his workroom. He had been standing there, staring down at me in disbelief as I ignorantly forged ahead with my attempts at gardening until he could take no more. Shame crept over me. I picked up the scythe and carried it to the tool shed, hanging it back in its place on the wall. I picked up the iron rake and returned to where I had been working, tearing it roughly over the ground until I had filled the wheelbarrow with lifeless, slippery stalks of grass.

The bicycle was just behind the tool shed, propped up against the wood stack, an old, lightweight, grey Peugeot with narrow road tyres and ram’s horn handlebars.

The cycle to the shop only took ten minutes or so. It was a small grocery shop on a corner, just across the bridge, the kind of place that time has forgotten. A bell tinkled above me as I pushed the door open. There were no other customers. An elderly lady stationed behind the counter offered me the briefest of nods as I entered. There were shelves stocked with packaged food, napkins and candles, a small selection of bread and dairy products; there was a freezer cabinet, and fruit and vegetables with a set of scales for customers to weigh their own items.

The shopkeeper’s eagle-eyed glare prickled at my back, her eyes following me as I wandered between the half-empty rows of shelves. There was no mistaking her critical air. She knew who I was. I felt a knot forming inside me, tightening, plucked a few items from the shelves and placed them in my basket, every move wooden, my only desire to put down my basket and leave. Eventually I approached her to pay, placing the contents of my basket on the counter without looking her in the eye. She entered the prices of each item into the register, her expression unreadable. Wrinkled hands and a wrinkled face, a small mouth that drooped downwards at both corners. It was just her way, I suddenly thought to myself, relief washing over me, it was nothing to do with me, it was just the way she was.

I raced home, flying along on the thin bicycle tyres, with the fjord to my left and the dark, glistening-wet rock wall to the right, my shopping packed away in the saddlebag by the back wheel, cars passing me on the road that connected the two neighbouring towns. I hurtled down the steep driveway through the forest before stopping my bicycle by the wood stack, crunching over the gravel, opening the door into the hallway and making my way through the house.

Something wasn’t right about this place; it was home to a married couple, yet the garden was a neglected mess, they owned no car and he locked himself in his workroom all day long. His wife away like this. I put the shopping away and started preparing dinner.

It felt impossible to move. My body was as stiff and leaden as the rusted wrought-iron gate. For a long while I lay and gazed up at the knots in the wooden ceiling planks before finally managing to roll myself across the mattress and down onto the floor. Ridiculous. When had I last done any kind of manual labour? Never, that’s when; or at least not until deciding to rake grass and dig away at solid earth for hours on end.

I staggered without a smidgen of grace between the kitchen and the table as I served his breakfast. Shame coursed through me; I knew that my ungainly hobbling vexed him. As I went to pour his coffee I let out a groan; it was hard to tell which of us was more embarrassed.

I think I went at things a little too enthusiastically in the garden yesterday, I mumbled apologetically.

He cleared his throat and stared straight past me.

After his breakfast he returned to his room without a word. Drinking the bitter coffee in solitude after he had left the room, my good spirits wavered. I had been so proud of my efforts the previous day, clearing the area of dead grass, all the while hoping that he’d catch a glimpse of me in action from his window. My back was so, so stiff.

The following day was worse. The simple act of placing one foot in front of the other was an almost unbearable ordeal, and I avoided sitting down all day long because I knew that I’d never be able to get back up again. My passion for gardening had lasted all of one day. It was always the way with me. I launched myself at things with gusto yet never saw anything through, always started with the same unbridled enthusiasm before swiftly giving up. I possessed no sense of perseverance, no will to accomplish anything in full. It was precisely this aspect of my character – an absence of resolve, my lack of self-discipline – that I had hoped might be transformed. But here was the thing: it required willpower to build willpower. A more dependable person, that’s what I had to become, a woman in possession of a firmer character. If not now, then when? Out here I had what little I needed: solitude, long days at my disposal, a small number of predictable duties. I was liberated from the watchful gaze of others, free from their idle chit-chat, and I had a garden all of my own.

On the evening of my seventh day, I set down the tray carrying the coffee pot and cup and the glass of brandy, and was just about to step back when he held up a hand, stopping me in my tracks. It was Tuesday. I had only been preparing his dinner for a week and had already run out of ideas. Today: chicken and tarragon. Monday: fishcakes and onions. Sunday: roast veal. Saturday: roast beef. Friday: fried fillet of trout with cucumber salad. Thursday: smoked sausages in a white sauce. Wednesday: poached cod.

Allis.

It was the first time I had heard him say my name.

Yes?

Fetch an extra cup and a glass and come and take a seat.

I did as he asked. He poured coffee into the delicate porcelain cup with a steady hand.

You’ve been here for a week now, he said, staring down at the edge of the table.

I said nothing.

Are you happy here? He looked up.

Yes.

Would you consider staying a while longer?

Absolutely. Thank you.

You’ll be paid after the first month. Does that suit you?

I nodded.

Do you have any questions?

I hesitated for a moment.

Do you have any idea how long there will be a position for me here?

I’ll need help in the house and garden for as long as my wife is away. All through spring and summer, to begin with.

That works for me.

He poured brandy into the tiny glass, then lifted it in my direction.

Then we should raise a glass.

I lifted my own, and without thinking I carefully touched my glass against his with an all-but-silent clink. We sat in silence. He exhibited no desire for conversation after that point, his forehead creased beneath his dark hair. I drank my coffee and the contents of my glass, and, before he finished his own, I left the table and made a start on the washing up. I heard him push his chair back and disappear into his room as I rinsed the dishes, cold in the knowledge that it was done, I would remain here, yet warm for the very same reason. I had a place to stay, no need to go back. I could live out here in peace.

After a few days of sunshine, the garden was beginning to dry out. I had finally honed my skills with the scythe, too, and now left an aftermath of spiky clumps of straw in my wake. I had started to perspire in the cool air. The pale afternoon light dwindled as the sun disappeared behind the mountains. My back aching, I gazed around me. Spring flowers could be seen here and there. One day there had been a brief flurry of snow, while the next a butterfly had unexpectedly landed nearby. There was no order to things. I dragged the rake through the hay and weeds, clearing the area and wheeling everything to the end of the garden in the wheelbarrow. Dark, compacted earth had become visible beneath the weeds: old flower beds. I hadn’t yet touched them, but it was possible that bulbs and seeds and life might be lurking beneath the surface, soon to emerge. Occasionally I would turn around and look up at the house as I worked, and would catch a glimpse of Bagge at the window, always in motion, so it was impossible to tell if he had been watching me or simply passing by.

I returned the tools to the shed, banged the work boots against the wall beneath the veranda to remove the clumps of earth stuck to the soles and made my way upstairs to my bathroom. I filled the tub and slipped into the water, scrubbing myself clean of dirt and earth, uplifted by the new possibilities of my existence. Good, hard work beneath an open sky, the feeling it left in my body, the act of drawing fresh air deep into my lungs. I had never thought change was possible. Not of one’s own doing, anyway. Never. The idea that I could transform myself had been nothing more than a notion I occasionally turned to for comfort only to find it depressing when I was forced to acknowledge that I didn’t really believe in it. But now this. Committing myself to this: to the work in the garden. Clearing space, making things grow. There was salvation to be found, I could create a sense of self, mould a congruous identity in which none of the old parts of me could be found. I could make myself pure and free from guilt, a virtuous heart. I pulled the plug and watched as the water was drawn down into the plughole. I rinsed my body and hair with the shower head, then stepped out of the bathtub. I heard Bagge’s footsteps on the floor downstairs – could he be pure? – then dried myself off, dressed and entered my room.

From my window I watched him head down through the garden, on inspection duty, perhaps, the heavy soles of his boots crunching over the dry tufts of straw, the sight of his broad back as he marched past the fruit trees and carried on, disappearing down the steps to the jetty. I felt a flutter in my stomach. Men, I thought, such beautiful creatures. Some of them, at least. Their voices, their backs. Quickly I left my room and tried the door across the hall. It was locked. I stopped at the top of the stairs and considered running down, hurriedly snooping around; the thought made my heart pound within my chest. I let it be.

His bathroom was to the right, just off the hallway: an old-fashioned tiled floor, an ordinary toilet and a simple shower concealed by a curtain. My instructions were to clean the room and mop the floor once a week. I could decide for myself which day I preferred to do it, he had told me, but had added that he liked to start the weekend with the scent of soap in the house.

As I filled the bucket with water in the kitchen, I saw him walk through the garden. He was tall and broad-shouldered and bowed his head automatically as he walked in and out of rooms. Outside he stood erect in his heavy hiking boots and walked at a slow pace, always moving silently in spite of his size. For no apparent reason as I watched him move through the garden in the way he did, I was reminded of the Norse god Balder. I liked to gaze at him as he walked away, to observe him from afar. He always wore button-up shirts, and when it grew cool in the evenings he would pull on a coarse, dark-blue woollen jumper. He was entirely uninterested in me, uninterested in everything. Everything besides whatever it was that was going on in his workroom. I tried to rein in my curiosity, to mind my own business, to concentrate on what I was doing in the garden that I had already begun to think of as my own, to focus on the task of meal-planning. In the evenings I wrote lists of what I had, what I needed, what I could cook and how I might best make use of the leftovers. It was the kind of task to which I could anchor the stream of thoughts that otherwise drifted so easily to darker places.

The door to the bathroom cabinet clicked softly. Inside were painkillers, plasters, mosquito repellent, a beard trimmer and a common brand of deodorant. It surprised me. I had almost taken for granted that he must be on some kind of medication or other. I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror as I wiped it down. It was clear that the person staring back at me had just done something that she knew was irrational; it was a look that I had seen a hundred times before. That’s quite enough of that, I thought; be pure.

I had been fortunate enough to find a gardening book on the shelf, but the information in it was sketchy, to say the least. It said that the bushes should be pruned before buds formed, but nothing about when buds might be expected to appear. I sat on a stool beside one of the nearest blackcurrant bushes and peered carefully at the branches. I had fallen into the habit of engaging in an endless inner dialogue with myself as I worked in the garden. I covered a whole range of topics. I’d always been sure that, if I ever went mad, I’d never be the type to wander the streets and talk aloud to myself, because I wouldn’t have anything to say; but here, in this silence, my hands plunged deep in the cold, damp earth or running along dead branches, I found myself simmering over with chitchat, endless conversations with myself, occasionally even imagined dialogues with others, discussing and debating for hours at a time. I lost each and every one of these internal disputes, listening more intently to my imaginary opponents than to myself, their arguments always holding more sway than my own. Other people had always been more reliable than me.

I started by removing the blackcurrant branches that looked as if they’d died over the winter, and after that all those at ground level. I finished by pruning the oldest branches on the bush. The growth rings on the cuttings suggested that the bush hadn’t been pruned for at least seven or eight years, and I found it odd that Bagge and his wife had neglected the garden the way they had.

When I finished, I took the loppers with me up the rocky bank to where I’d found hazels growing. If I pruned them now, they might produce a decent yield of nuts later. Shuffling around the garden and carrying out these little jobs to the best of my ability was a delight, but it also involved navigating a narrow path of self-understanding. If I’d had any horticultural expectations of myself before coming here, these had now been quashed, for I now had to admit to the fact that my knowledge of gardening and plants and soil was uniquely lacking in comparison to everyone I knew. I was clueless; in truth I harboured a major inferiority complex where the subject was concerned. Perhaps I should have shown more interest, but the fact that earth couldn’t simply be left to be earth, but had to be fortified with manure or nourishment of some kind, the fact that nature couldn’t work things out for itself – these had always been the major obstacles that stunted my enthusiasm for the whole thing. In the tool shed I stumbled across a selection of old seed packets, but the text on the back was incomprehensible to the average person, all about thinning distances and who knows what else, all conveyed in a language the likes of me found difficult to grasp. I memorised short passages from the gardening book, and went out the following day to put what I’d read into practice, attempting to visualise the contents of my memory: Like this? Is this what they mean? I froze as if to ice whenever I was struck by the thought of Bagge watching me from the window, standing there, scratching his head: What on earth is she up to now? No, no, not that one! At first I didn’t dare attempt anything more advanced than a haphazard spot of weeding in the recently discovered beds. But now I had pruned the perennials as I thought they ought to be pruned, and I was even considering planting some bulbs, though the author of the gardening book seemed to assume that everyone on the planet already possessed both the requisite knowledge and his or her own tiny arsenal of bulbs, primed for deployment when spring came; I was at a loss.

I raked up the hazel cuttings and lifted them into the wheelbarrow, then trundled over the lawn and dumped the contents with the rest of the green waste. Light suddenly pierced the dark sky, the rays unexpectedly warm and intense. I perched myself on the dry stone wall for a break, the warmth of the sun on my brow, then closed my eyes and turned to face it, my back to the house. Sighed. Perhaps gardening was for me after all; perhaps I just hadn’t had a chance to find out before now, hadn’t ever learned how. I’d pick it up, it’s hardly as if I had learning difficulties, I’d always been quick and there was no reason to assume I was some kind of horticultural dyslexic.

Stay perfectly still, Allis, I suddenly heard just behind me, his voice strangely quiet.

Without thinking I turned my head and looked at him, inquisitive. I screamed as he leapt at me, a pouncing lion, springing at me with one decisive, snarling, crushing blow. I fell forwards, down onto the grass, no notion of what was happening or why, shamefully lingering there on all fours like a dog.

He dropped the rock he had been clutching, took my hand and helped me up, I was dizzy with adrenaline, my breathing panicked, shallow. There, on the dry stone wall where I had been sitting, lay a coiled-up adder, its skull crushed.

I didn’t mean to frighten you.

I couldn’t utter a single word. My heart thumped as I took an unsteady step back.

We gazed at the adder, steam rising gently from the animal’s body, a long, patterned muscle in cramp, only a glistening, wet void where the head had once been. I shuddered.

Not bad, I squeaked, conscious that I was breaking out in a cold sweat.

He picked up the snake by the tail without a word and strode up the bank as it dangled from his hand, making his way to the edge of the forest. I saw him crouch down and place a rock on top of its body. He walked across the garden towards the house, grasped the door handle and was gone.

The evenings had started to become noticeably brighter. I took the bicycle out to investigate the local area, though there was nothing to see. There were scarcely any houses, only the main road, cars whizzing by. The grocery shop was my only contact with the outside world, and there were still no other customers to speak of, only the same old woman behind the counter, glaring at me over her crooked beak.

The house was as quiet and empty as always. Knowing there was another person here but seeing no sign of him other than at mealtimes made it feel all the emptier. I washed the vegetables at the kitchen sink and began making stock with some leftovers. I was out of ideas about what I might make him for dinner the following day. If I had properly thought things through before getting on the bus a month ago, I might have had the sense to pack a recipe book. I ambled over to the bookshelves to see if there was anything resembling a cookbook hiding between the volumes on show, but examining the spines I found nothing. A house without recipes, what kind of home was that?

I opened each of the kitchen drawers in turn, then the cupboard doors. Slipped in alongside the spice rack I found a slim, blue volume that I hadn’t noticed before. I pulled it out and carefully leafed through its pages. Recipes scrawled in fine, black script. Beautiful, cursive handwriting describing casseroles, soups, cakes. I pictured her, an indistinct, slender figure standing with her back to me, the nape of her neck tanned, her dark hair coiled in a bun with a few curly, flyaway strands by her ears. A beautiful, mature woman. A queen. Mature, I thought, am I not mature? No, a lost child, that’s what I am. I stopped at one recipe, an Asian fish soup, realised that I had most of what I needed to make it and decided to cook a small batch, a trial run for dinner that evening. I warmed oil in a pan and added spring onion, chili, ginger. The scents drifted upwards. I added stock and placed a fillet of cod in a separate pan to poach. Just as I was preparing to lift the fish from its pan and add it to the soup, I heard footsteps, the door opening. I blushed and cursed inwardly; I had disturbed him. He stuck his head around the door; I pretended not to notice him.

It smells good in here.

Just a little soup…

I see.

There’s plenty here for you too, if you’d like to try some.

Confounding my expectations, he entered the room and sat down at the table as if in anticipation of what was to come. I grew clumsy in his presence. Hurriedly I slipped the recipe book between two chopping boards, ladled the soup into a bowl and placed it on the table before him. He closed his eyes and inhaled deeply then looked up at me, surprised. I ate my own portion standing at the kitchen worktop while he sat at the table. Neither of us spoke. Watching him eat left me with a sense of calm, a warmth. He devoured every last morsel, then took a slow, deep breath and pushed his chair back from the table. He stood up, picked up his empty bowl and walked towards me, stopping directly in front of me and placing the bowl on the bench beside me. Hot-cheeked, I looked down until he had returned to his room.

T