Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- E-Book-Herausgeber: Orenda BooksHörbuch-Herausgeber: Isis Audio

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

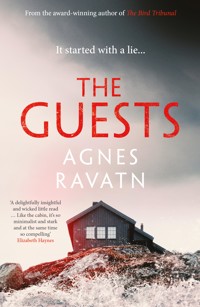

A young couple are entangled in a nightmare spiral of lies when they pretend to be someone else …Exquisitely dark psychological suspense by the international bestselling author of The Bird Tribunal `A delightfully insightful and wicked little read … Like the cabin, it´s so minimalist and stark and at the same time so compelling´ Elizabeth Haynes ________ It started with a lie… Married couple Karin and Kai are looking for a pleasant escape from their busy lives, and reluctantly accept an offer to stay in a luxurious holiday home in the Norwegian fjords. Instead of finding a relaxing retreat, however, their trip becomes a reminder of everything lacking in their own lives, and in a less-than-friendly meeting with their new neighbours, Karin tells a little white lie… Against the backdrop of the glistening water and within the claustrophobic walls of the ultra-modern house, Karin´s insecurities blossom, and her lie grows ever bigger, entangling her and her husband in a nightmare spiral of deceits with absolutely no means of escape… Simmering with suspense and dark humour, The Guests is a gripping psychological drama about envy and aspiration … and something more menacing, hiding just below that glittering surface… _____ Praise for Agnes Ravatn **Shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award** **A BBC Book at Bedtime** **Shortlisted for the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Fiction** **Winner of an English PEN Translation Award** `A clever, quirky mystery, full of twists and reminiscent of Agatha Christie at her best´ The Times `Ravatn, one of Norway´s premier crime writers, manages to conjure up an extra level of chilling atmosphere that will make you want to put the heating on´ The Sun `An unrelenting atmosphere of doom fails to prepare readers for the surprising resolution´ Publishers Weekly `Unfolds in an austere style that perfectly captures the bleakly beautiful landscape of Norway's far north´ Irish Times `Reminiscent of Patricia Highsmith and I can't offer higher praise than that. Agnes Ravatn is an author to watch´ Philip Ardagh `A tense and riveting read´ Financial Times `Crackling, fraught and hugely compulsive slice of Nordic Noir tremendously impressive´ Big Issue `Intriguing … enrapturing´ Sarah Hilary `A masterclass in suspense and delayed terror´ Rod Reynolds

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 217

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das Hörbuch können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Married couple Karin and Kai are looking for a pleasant escape from their busy lives, and reluctantly accept an offer to stay in a luxurious holiday home in the Norwegian fjords.

Instead of finding a relaxing retreat, however, their trip becomes a reminder of everything lacking in their own lives, and in a less-than-friendly meeting with their new neighbours, Karin tells a little white lie…

Against the backdrop of the glistening water and within the claustrophobic walls of the ultra-modern house, Karin’s insecurities blossom, and her lie grows ever bigger, entangling her and her husband in a nightmare spiral of deceits with absolutely no means of escape…

Simmering with suspense and dark humour, The Guests is a gripping psychological drama about envy and aspiration … and something more menacing, hiding just below that glittering surface…

THE GUESTS

Agnes Ravatn

Translated by Rosie Hedger

Contents

The Guests

The archipelago elite grew closer with every right turn. Effortlessly well-turned-out, nut-brown couples appeared on the horizon, one after another, increasing in number as we approached our destination. Our orange van made for a clownish addition to the black electric SUVs.

We eventually turned onto a narrow gravel track that ended without warning at the edge of a towering precipice.

Here, then? Kai said, turning off the engine as I looked up from the map on my phone and out at the view before us.

This was the land of soft, smooth, coastal rocks, worn away over twelve thousand years.

This must be it, I said.

Neither of us even wanted to stay at the stupid cabin in the first place. For once, my in-laws had invited our boys to stay over at theirs, and Kai had booked the entire week off work. I had been completely prepared to spend the week taming the garden while he finally finished work on the decking – ten years after we’d bought the house.

I wasn’t a fan of the archipelago lifestyle; it simply wasn’t for me. Never had been. I was too burdened by self-reflection, too exhausted, too uncomfortable in my own skin and in the clothing I wore, as if I should be wearing someone else’s – not that I had any notion of whose.

Kai, on the other hand, was adaptable.

When I told him we’d be staying in a cabin rather than working on the garden, for example, and not only that, but that I’d also got him a job, he’d reacted with only mild surprise.

It’s a paid holiday! I’d said, typing the cabin’s location into the map on the iPad, a grey rooftop nestled among the white rocks and sparse vegetation, I zoomed in so close that we could see the benches and huge stone table in the outdoor seating area.

Some of us have to work on this so-called holiday, he said.

But it’s so close to the sea! I’d said. And hardly another cabin to be seen anywhere nearby!

But Karin, I thought we’d agreed… he began, but when I zoomed in on the white boat he trailed off mid-sentence, and I could practically see him making a mental list of all the extra fishing gear he would have an excuse to buy.

That was Kai all over, ready to turn anything into a positive, much more so than I ever could, a fact that he was always keen to highlight.

We took our luggage – Kai with his nautical-looking canvas bag, me with my impractical, unsuitable suitcase on wheels – and lugged them along a dry path that wove its way through the natural vegetation, great tufts of sea thrift tucked between tall, tough, shiny blades of grass, until we made it onto the smooth coastal rocks. I’d only ever seen rock formations like this in pictures; there were pink and orange and brown hues amidst the grey, rippling and rolling before us, almost soft underfoot.

Water appeared up ahead, a view of what surely had to be Skagerrak strait – was that the ocean or the sea? – and I stopped in my tracks.

Such a shame, I said, shaking my head. Detonating a pathway through an untouched natural landscape like this, just to create a holiday paradise for the well-heeled.

Kai looked at me.

I don’t think anyone’s been detonating anything around here, have they? he said.

In general, I mean, I replied, hauling my suitcase behind me.

I felt a creeping sense of discomfort as I approached the spot where Iris Vilden’s cabin was said to be located. I took in the view. A gentle, salty breeze and the predictable screeching of gulls, but no sign of any cabin. According to the blue dot on my phone we were here, standing right beside it. It occurred to me that the whole thing had been one big practical joke, that there was no cabin, that Iris was sitting at home giggling away to herself, but then I heard Kai shouting: Over here!

He was standing on a rock ten metres ahead of me. I climbed up to join him and immediately caught sight of the cabin. It was nestled perfectly within a natural dip in the rock, beneath two huge, rounded boulders and behind five low, windswept pines, barely visible from any other angle besides the one from which I was looking at that moment.

Wow, Kai murmured as we made our way down a flight of steps cast in concrete between two boulders.

The cabin wasn’t as showy and vulgar as I’d hoped it might be, in fact, it was tasteful and understated, constructed from greying wood, glass and natural stone.

Well, this is, hmm, I said, unable to think of anything to say. I’d been anticipating something a little more offensive and garish, easier to find fault with. There was nothing here for Kai and I to ridicule and mock, at least not at first glance, nothing we could exploit in order to strengthen our own bond, only a wealth of environmentally friendly materials and extreme privilege.

A week here, I thought to myself, and already I felt drained, a week!

Kai ambled onto the patio and placed his bag on the table – a monstrous stone block balanced on two smaller ones – then turned to look out at the sea and took a deep breath in through his nose.

Inviting us out here was an attempt on Iris Vilden’s part to provoke a bout of jealous self-reflection: why couldn’t I even imagine such a cabin when she was in a position to own one?

I picked up my phone once again, opened the app to unlock the door and pulled up the code she’d sent me. I typed it in. The door clicked abruptly.

The inside of the cabin was more like a Scandinavian interior-design showroom than a holiday home for actual, real-life people.

I stepped into the cool hallway.

Wow, I mean, this must be worth what, twenty, thirty million kroner? I said slowly.

At least, Kai said.

How on earth were they even allowed to build this place? I asked.

They must have bought an old shack and sought planning permission to demolish it and build another in its place, he said.

But I mean, this is a conference centre, I said.

I’m going to take a walk and check out the jetty, Kai said, before turning around and walking out.

You’ve become so blasé about these things, I called after him. He’d worked on so many fancy cabins in and around the Oslo fjord that nothing impressed him these days.

It was silent inside the cabin itself, in contrast to the gusts and the screeching of the gulls outside. The pale floor gleamed at me, they were the widest floorboards I’d ever laid eyes on.

Kai’s silhouette passed the enormous window that looked out over the water; it wasn’t a window, not really, more like a transparent wall.

I parked my suitcase in the middle of the room and took in the space around me.

It had light-coloured wood-panelled walls, and these had been adorned with what I could only describe as modern art, stuff that went over my head.

A three- or four-metre-long dining table with a vast tabletop of what had to be oak, filled the space. Ten matching chairs, no doubt all crafted by hand. In the corner by the sofa a huge, glass-fronted wood-burning stove.

I turned around to take in the kitchen. The cabinet doors had been crafted from the same wood as the pale, oiled floorboards, not the kind of thing you could buy off-the-shelf from any old kitchen showroom.

A half-metre-wide, mirrored-chrome espresso machine took centre stage on the black stone worktop. There was a gas hob, an oven, what could have been a combi steamer, and a third unidentifiable type of oven, all stacked on top of one another. All of this for a cabin?

Kai and I had actually decided not to bother with a holiday this year. Kai was keen to squeeze in as much work as possible; the building trade was experiencing a bit of a slump, everyone was holding off on doing any building work due to the rise in costs. Rather than tackling the major work, people were ticking off the small building projects, and his phone never stopped ringing.

But the fact was that we had less cash to splash, in spite of the fact that we both worked full-time and never spent very much.

While it seemed that other parents in the area met Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for their children without issue, providing endless hoodies and pairs of shoes and pieces of ski equipment, the prices of which were inversely proportional to the ever-decreasing number of snowy days each year, Kai and I were forced to pinch the pennies.

I felt as if I was here under duress, it weighed on me like a heavy mass. I wanted to turn around. To drive home and send Iris a message to say that something had come up. But then it struck me that she could probably see from the door-locking app that we’d already arrived, and was no doubt waiting to hear from me to that effect.

There was only one picture in the entire cabin that wasn’t an artistic abstract, the only indication that real people resided here, and it was a photograph on the wall between the bathroom and the master bedroom. A family of four photographed against the setting sun. Two small, tanned boys around the same age as my own, with big white grins and grains of sand on their shoulders, the wind-swept hair of surfers, bleached white by the sun and thick with saltwater.

Iris beamed in an exaggerated fashion; she was wearing a white bikini top, with her left arm disappearing out of shot behind the camera.

Standing in the house behind them was their father, a tall man in a basic, white T-shirt with a cap on his head backwards and sun-bleached hair sticking out each side, his face clean-shaven. A smug, masculine smile into the camera, two long, strong arms, she’d found the male version of herself. All of a sudden, I was overcome with fury at the fact the world is just like she is: how can it be that waiters, for instance, take one glance at my children and me and somehow intuitively understand that we don’t deserve the same level of service as Iris and her children, how is it that they can decipher the tiniest of signs, the quality of our clothing, our haircuts, our complexions! – and why do we just accept it all?

What’s up? Kai asked, appearing behind me all of a sudden, I’d let out an impulsive, loud snort without realising it. I turned around to face him.

What exactly am I supposed to do out here? I asked him.

Come on down and take a look at the boat with me, he said excitedly.

I’m tired, I said.

You’re just hungry, he said. I’ll bring in the food shopping.

He turned around and walked out.

The food shopping, I thought to myself. Sliced bread, butter, Kai’s seedless jam, the kind kids like, plus ham, cheese, cucumber. All very lower-middle class. I took a deep breath, I couldn’t, wouldn’t, let Iris win by descending into this mire of self-pity.

I grabbed my phone and started writing a message to her.

We’re here. What a lovely place! followed by a bog-standard smiley. As I reviewed my nonchalant message designed to belittle what was hers, I saw three little bubbles appear on screen, Iris writing a reply, then they vanished.

I sat down on the sofa, surveyed the panorama that expanded before me, and thought to myself that it would be good for me to spend this holiday trying to adopt Kai’s uncomplicated approach to his position in this universe. He wasn’t prone to envy, unlike me; he didn’t instinctively compare himself with others, he was capable simply of observing things with interest, his head cocked to one side.

For me, this cabin held no value simply because it wasn’t mine, it never could be, and it could not, therefore, offer me anything other than a greater sense of defeat regarding my lowly position in the food chain.

My phone vibrated, a poorly disguised expression of Iris’s disgruntlement: Great!, followed by an aggressive emoji, a smiley face that looked as if it were howling with laughter or pain. I considered it a tiny triumph, stood up and made my way towards the kitchen, which was so stunning that it left me incapacitated. I decided to knock up some sandwiches for lunch.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I actively dreaded the prospect of being reunited with Iris Vilden, but I had spent my adult life hoping, more or less subconsciously, to avoid bumping into her again.

During my first few years in Oslo, I’d looked up her address once a year or so, just to be sure that we wouldn’t encounter each other.

She’d always lived in the city centre. I had always lived in the north-east of the city, and in the years that passed, I’d gradually moved further and further away from the centre, eventually ending up across the county line, settling in the neighbouring municipality of Nittedal, way down south in Skillebekk.

While Kai was a professional one-man-band with a niche skill, which was creating space-saving interior-design solutions – making use of jamb walls, built-in bookshelves and beds, and so on – and which had him whizzing up and down the entire east coast in his orange Ford Transit van filled with tools, I was confined, day in and day out, to the same office in Nittedal City Hall, where I had willingly ended up working as a consultant after completing my law degree, and where I had spent almost ten years advising on quality improvements and internal regulations, a role for which I felt both over- and underqualified.

I rarely found myself in Oslo city centre, so the threat of bumping into Iris Vilden was far from imminent.

Then, in May, Kai had surprised me with a pair of concert tickets. Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 had never been a real favourite of mine – quite the opposite, in fact – and our seats were some of the worst in the house, but none of that mattered, because Kai had made the effort to go online and order them for my birthday, and that in itself was more than enough of a gift for me.

And it’s a funny thing. Two hours in the company of the Oslo Philharmonic and five different choirs, it does something to a person. It was a powerful experience. Even Kai felt it, sitting there awkwardly in his best jacket, his hair dishevelled, his face bristly with three days’ worth of thick stubble. He stuck out like a sore thumb, thanks in no small part to his slightly wonky nose – the result of an accident at work many years ago – which made him look like something of an outlaw.

He was pale when we stepped outside afterwards. I need a drink, he said, and I felt the same way. We made our way to a pub on Rosenkrantz gate, where we had a pint, then one more.

And just as I was about to say that we ought to be making our way home to relieve our babysitter from her duties, the door opened, cold air filtered into the pub, and the icy breeze ushered a high-spirited, carnivalesque troop inside.

I glanced at the door and froze. It was her.

Quick, I said to Kai, hide me!

He looked at me, puzzled.

Hide me! I repeated. He grabbed his coat and tentatively held it up like some sort of curtain, and I whispered, We have to leave, NOW. It was a spontaneous, natural reaction, instinctive, animalistic. The coat muffled the commotion in the pub as I tried to figure out an escape route.

By the bar, I whispered, and Kai pulled a face – what’s going on? – as I carefully stood up. Kai picked up his glass and finished the contents before standing up beside me. I cleaved to the walls, treading carefully, it was a Friday night and the place was packed with boisterous, inebriated punters to hide behind, but out of the corner of my eye I realised that somehow, by some miraculous twist of fate, she had managed to catch sight of me, and we were summoned.

KARIN? she bellowed hoarsely from across the pub, and rather than pretending I hadn’t heard her, I stopped as if on command. She slithered her way through the bustling crowds like a jaguar, cutting us off just as we reached the bar.

My God, she said, looping a tentacle around my wrist and drawing me in towards a cheek that sparkled with stage makeup. My God, it must be, what? – and I could see her unsuccessfully trying to guess how long it had been since we’d last seen each other.

Twenty-five years, I said.

My God, she repeated, her mouth agape, then she caught sight of Kai behind me, his coat now under his arm.

Have we met?

Oh yes, I said, this is…

Kai offered an outstretched hand. I’m Kai, he said, nice to meet you.

She was wearing some sort of black, floral, low-cut kimono, she turned around to look at me, her mouth still wide open.

We were just leaving, I said.

You don’t want to come and sit with us? she asked, and she nodded in the direction of the group she’d arrived with. We’re celebrating the opening night of my one-woman show at Oslo New Theatre.

Oh, wow, I said, congratulations.

Then a moment of silence.

In my naivety, I imagined that she might want to apologise, what with her being a grown adult woman now, perhaps she was a mother, perhaps she could see things in a new light, but instead she said: And how about you, what did you end up as?

A lawyer, I said.

Of course, Iris said. You always did have your head in a book. So, are you in the courtroom much, or is it one of those boring office jobs?

A boring office job, I said.

She looked around then leaned in. The corners of her mouth were two sharp points, and her top lip stuck out and up in such a way that her front teeth were visible even when her mouth was closed. I’d always felt that it made her look like a big kid, as if she’d sucked a dummy for too long, but other people probably found it erotic.

Funny that I should bump into you, of all people, she said, lowering her voice. I’ve got a subtle little legal dilemma on my hands, as it happens.

What Iris Vilden referred to as a subtle legal dilemma – I was sure she meant ‘sensitive’ – was no dilemma at all; a dilemma suggests the need to choose between two unpleasant options. What Iris Vilden actually wanted was for me to help her benefit from a greater proportion of her production’s profits.

The distribution of profits between Iris and the writer of her show was all wrong, she told me, she had written large sections of the play herself, not to mention the fact that she’d made use of material from her own life, all of which added up to her being responsible for at least a third of the writing, by her estimate. In spite of this, she said, the writer had run off with all the money.

This isn’t really my area of expertise, I told her, and my response caused her brow to arch dangerously.

It had always been difficult to say no to her, even when we were young. I’m not sure whether that said more about me than it did about her, whether she was particularly persuasive or I was easily persuaded.

But, in general… I went on quickly, and her expression softened.

Even though this was clearly an agreement she must have entered into long before the show opened, a fact I couldn’t help but point out, I advised her to ask for a meeting with management. I listed three or four arguments she could use in that meeting.

She repeated the points aloud, word for word, asked me to go over them at least seven times, which served only to remind me just how stupid she’d always been at school. Nevertheless, she had somehow landed on her feet – in a career that required her to memorise scripts by heart. She had landed on her feet in the same way she’d always done, I imagined: by making herself irresistibly helpless around men.

As soon as she had a handle on the arguments I’d presented, she thanked me briskly and bid us goodnight before returning to her loosely formed company, who were still busy applauding and laughing.

Nothing had changed, in spite of the fact that I was now a forty-one-year-old lawyer and married mother of two in possession of my own home on the edge of the forest. In spite of all of this, she had me in an iron grip.

I dragged Kai through the pub and let out a heavy sigh when we finally found ourselves back outside.

Why did you want me to hide you? Kai asked in bewilderment, and I shook my head.

I was quiet on the way home. He tried asking me what it was all about, but I just stared out of the window.

Was she a childhood friend? he asked, making another attempt to engage me on the subject as we made our way out of Vestli Station and embarked upon the twelve-minute walk home. It was a bright summer evening, but it was chilly. I wasn’t dressed for the temperature, and he wrapped his jacket around me before I had a chance to respond to his question.

Iris Vilden had moved into the area and started at our school in year four, seamlessly and harmoniously embarking upon a life that became a daily remake of Lord of the Flies. She was blessed with a phenomenal talent for manipulation and for restructuring social constellations. She reigned over us like a one-woman swarm of grasshoppers, razing friendship after friendship to the ground, freezing people out, spreading rumours and then making peace again in a monstrously finely-tuned come-in-from-the-cold routine.

You never knew which day it was: would it be your turn to experience humiliating loneliness during breaktime, or someone else’s time to be put through the mill?

The intense relief and delight we felt at being included in the muted warmth that young Iris Vilden seemed to emanate left us powerless to coordinate any form of protest, we were helpless to resist. There was something weirdly democratic about it all too, she was our elected leader.

What I remember most clearly was the unadulterated joy we felt when we found ourselves in Iris’s sights. But she didn’t carry on the way she did because she was having a hard time at home or struggling with her self-image, it wasn’t a symptom of something else, as I tend to tell the boys whenever they witness someone being unkind: they’re just sad about something, I say. No. She delighted in what she did, pure and simple.

Then one day, one otherwise normal day in year six, everything changed; I had a divine moment of clarity and realised that I didn’t actually need to be part of her court. It was that simple. It took only a split second for Iris to lose the power she held over me. On my way out of the classroom, I slipped away from her and attached myself to the small sub-category of girls in our class that lacked any real street cred, an innocent, less well-proportioned group of individuals.

There turned out to be a glorious sense of freedom in that resignation. A much more comfortable existence that I enjoyed well into high school, even though I was still in Iris’s class there too.

During my time at high school, my father, a cautious and precise man, was the deputy head teacher. This had very little real impact on my life until one spring day in year nine, when he stepped in as our substitute teacher for maths.

Towards the end of the lesson, as he made his way around the classroom to help each of us with our work in his own gentle way, a commotion broke out at the back. It was Iris making a racket, and I turned around to see my father draw back with a look of terror on his face, as if he’d been burned, as Iris shouted, Don’t touch me! Then looked up at the class: He touched me! She stood up and stormed out, swiftly followed by her two most loyal supporters.

She sat on the stairs during break and wept as the two girls comforted her; a breaktime supervisor came over to speak to her and the news spread through the school like wildfire.