Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

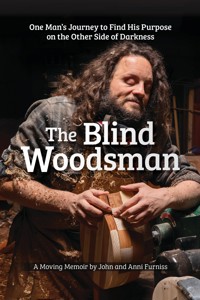

The Blind Woodsman is an inspiring and motivational autobiography about a man who finds true joy after struggling with depression, drug addiction, anxiety, financial despair and a failed suicide attempt at the age of 16. John Furniss, more famously known today as "The Blind Woodsman," along with his wife, inspiration and fellow artist Anni share their amazing story with the mission to help others. Despite being blind, John is now a highly skilled woodworker creating incredible pieces of art in complete darkness. Chapter one starts with how John and Anni met preceded by John sharing his experiences as a young teen and challenges along the way. Be inspired by the amazing images of John's work and many inspirational messages that will make you laugh and smile along the way. A story that will give hope and inspiration to those dealing with depression, addiction and the many anxiety driven stresses in our lives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Authors

John and Anni Furniss are a married artist couple living in Southwest Washington with their dog, Pickle.

John is completely blind and has been a woodworker for almost twenty years. He is a suicide survivor who is passionate about sharing his story to help others. He can also often be found doing talks in local schools about mental health and blind awareness, with Anni by his side.

Anni has been a mixed media artist—including painting, photography, sculpting, and fiber arts—for almost thirty years. She uses art as therapy. She has a hypermobility condition, and she loves spreading awareness about using art as a tool to help mental and physical challenges. Anni worked at the Vancouver Community Library for fourteen years and spent many years volunteering to organize community events such as fundraisers and art shows.

Together, John and Anni have created an online community dedicated to mental health awareness, disability advocacy, and art that now has over two million followers. This is their first book together. Follow them on Instagram, TikTok (@theblindwoodsman), or Facebook (John Furniss, The Blind Woodsman).

© 2024 by John & Anni Furniss and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

The Blind Woodsman is an original work, first published in 2024 by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder.

Paper ISBN: 978-1-4971-0451-8eISBN 978-1-6374-1328-9

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

Managing Editor: Gretchen Bacon

Acquisitions Editor: Dave Miller

Editors: Joseph Borden, Philip Turner

Designer: Matthew Hartsock

Proofreader: Sherry Vitolo

Cover images by Nolan Calisch.

All photography by Anni Furniss unless otherwise indicated.

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Foreword

I’ve written and played instrumental acoustic guitar music most of my life. Over the years, I’ve released quite a lot of music, much of which has been used for TV, film, and advertising. With the advent of social media and short-form content, my music found a new home being used as background music for videos. So it was that I learned of John’s woodworking. When I first saw one of his videos using my music in the background, I was so moved—not only by his work, but also by the thought and appreciation that had gone into using my music. Shortly after, I saw another video in which John said my music was his background workshop music while working. Truly, there’s no greater joy for me than something like that, for my music to be invited into another creator’s most sacred space. We quickly developed a friendship that has grown deeper over time. Though I’ve never met John and Anni in person, I feel like they’ve been lifelong friends. By the end of this book, I’m sure you’ll feel the same.

People don’t always remember what you say, but they remember how you make them feel. Art, music, and compassion are some of the best ways to create connection with people. In all they do, John and Anni strive to create this connection, and I think people will remember them for the positivity they’ve spread, and for how this book made them feel. John and Anni’s story is one of love, resilience, creativity, and inspiration, born and nurtured in the heart and expressed through the hands.

Music is more than the sounds emitted when an instrument is played; it’s the silence between the notes. So, too, are the pauses in the trek of life. This mindfulness is a big theme in this memoir, and I think it’s something many of us struggle with. I’ve often found myself wishing I could slow time down and truly experience every moment, good and bad, big and small. This is how John often experiences the world. Throughout these pages, you’ll see the quiet, important moments he and Anni share, and you will see the impact these have over the whole of their lives.

Neglecting to take these reflective pauses can lead us into darkness, a theme evident in John’s story. Moving forward requires vision, which often demands effort and cultivation. John exemplifies this beautifully. His transformation, akin to a wood block reshaped on a lathe or a tree repurposed as an instrument, mirrors how we all can evolve. His journey demonstrates our own potential for transformation.

When John lost his sight, he had to make a pivotal choice: surrender or rebuild. Sometimes, it’s in our toughest moments that we start anew, and John serves as a reminder of the potential within us to transform these into our greatest achievements. This won’t happen overnight, but if we choose to feel gratitude and find joy in the small things it can happen.

This memoir reminds us that we are more than our fears, anxieties, struggles, disabilities, or circumstances. In John’s own words, he’s not a blind woodworker. Rather, he’s a woodworker who is blind. John has known a profound darkness in a way I can only begin to imagine, yet he not only found light in that darkness but has become that light, alongside Anni, for so many others. His story invites us to leave stereotypes behind and see the amazing abilities in people, able-bodied or otherwise, serving to make the world a kinder, better place.

People used to frequently ask if I sang, and I’d answer with a quote: “Where words fail, music speaks.” My guitar is my voice. Similarly, John’s woodworking and Anni’s art are their unique voices, expressing their inner selves. Each piece they create is a captured moment, a chance to reflect and cherish life.

The power of love between two people is also evident throughout these pages. Although their story reads like a fairytale, they are both honest in sharing their pain and struggles, not only in previous relationships but in their own as well. This is powerful and encouraging, giving us hope that we can all build and nurture love. Anni’s influence in John’s life and work is a beautiful example of partnership in its truest form. What makes them work so well together is their team approach to conflict. It’s not about competition or who’s wrong and who’s right. When faced with a problem, they solve it together, and this has made them stronger in all respects.

John’s story reminds us what a gift life can be, or what a gift we can make it. I was moved to tears more than once, simply remembering that truth, one that’s easy to take for granted. We all know that we should slow down more often, be more mindful of ourselves and those around us, and enjoy the small things, but it’s easier said than done. We need constant reminders, and this memoir is a powerful one.

Whatever your story, you will find connection in John and Anni’s journey. This is not a self-help book, but if you are going through something and you feel surrounded by darkness, I can’t think of a better example to help shine light on your situation and maybe give you a glimmer of hope for a brighter future. If nothing else, I can guarantee you will feel like you’ve made some new friends by the end.

What you’ll also find here is a celebration of life, as it is. It’s about how we always have a choice, no matter how dark the situation may seem or how rocky the road that’s led us there. It also shows us how we can appreciate the good times. If there’s one unifying message, though, it’s that love conquers all. This book is a rallying cry to lead with love, treating others with kindness, empathy, and compassion, and I hope it will help you to find light in your own life and, as John and Anni have, spread that light to others without reservation.

—Alan Gogoll

World-Renowned Solo Acoustic Guitarist

Contents

Foreword

CHAPTER 1:Keys to the Heart

CHAPTER 2:Walking through the Darkness

CHAPTER 3:Losing Sight, Gaining Vision

CHAPTER 4:Rebirth

CHAPTER 5:Love Is Blind

CHAPTER 6:Back to the Sawdust: Starting Over Again

CHAPTER 7:I See You

CHAPTER 8:The Steps in Between

CHAPTER 9:Leap of Faith

CHAPTER 10:Such Great Heights

CHAPTER 11:Life Is but a Dream

CHAPTER 12:If You Can’t See, Imagine

Blindness Education

CHAPTER 1:

Keys to the Heart

ANNI

Our story sounds made up. But to cite a familiar saying, the truth is often stranger than fiction. In our case, it’s better.

In early July of 2012, a friend told me about a volunteer opportunity to paint a piano that would be auctioned for a fundraiser to benefit a local school. She knew I was always looking for something to keep myself busy. Having grown up in Vancouver, Washington, I was very familiar with the school. It was nicknamed “The Piano Hospital” because it was a repair business. It was also unique because the students who attended all had one thing in common: they were blind.

This day, I was painting a small spinet piano, which happened to be blocking the doorway to a classroom. As far as I knew, I was the only person in the whole school other than a couple administrative folks on the other side of the building. I heard some shuffling and looked up to see a tall man with a white cane bump into the side of the piano and place his hand on top of it, smack dab into wet paint I had applied to the instrument. I was a little embarrassed and could tell he was, too.

He held his hand up, smiling and asking, “Did I do much damage?” Luckily, the paint had been drying for a bit, so there wasn’t much on his hand. He had a beautiful smile, with big dimples, and his eyes were totally closed.

I apologized and stood up from the floor where I’d been working. Putting my own paint-covered hand out to shake his, I smiled and waited. And then it dawned on me. He couldn’t see my hand hovering in the air in anticipation.

So, a little too loudly, I said, “My name is Anni.”

Later, the fact that John was working on something called bridle straps when we met felt like kismet to me, a foreshadowing of things to come.

He chuckled. “I’m John. Nice to meet you.”

He wiped his hand on his khaki carpenter pants just in case there was paint on it. It’s funny to look back, all these years later, and see how this was a perfect meet-cute, like we were starring in our very own rom-com.

“Are you working in here? I can find another space if it’s too crowded.” I was a little nervous, and my voice shook as I replied.

“No, it’s okay, the more the merrier. Would be nice to have some company. It gets a little quiet around here during the summer.”

I looked behind me, realizing he had a workstation already set up nearby. John glided past me gracefully, using his white cane to navigate the tight space of the classroom.

“Bridle straps,” he said. I didn’t reply.

Sensing my confusion, he laughed and said again, “Bridle straps. That’s the project I’m working on.”

He held up what looked like a dangly, bendy matchstick made of ribbon. It was about three inches long. The thin, white strip appeared to be made of fabric and was capped off with a short, oblong red tip.

“They make it easier to remove and reinstall the action from a piano,” he said. He was now sitting on a tall stool by his workstation and trimming the end of each strap with a razor blade.

Later, the fact that John was working on something called bridle straps when we met felt like kismet to me, a foreshadowing of things to come. This would be the first of countless serendipitous moments in our relationship.

“You’ll have to forgive me. I don’t know the first thing about pianos. What is an action?” I asked.

“Think of it as the engine of a piano. It’s what makes the whole instrument work.” He spun slightly on his stool and pointed across the room. “I think there is an exposed action on a piano over there somewhere, if I’m not mistaken.”

He got up and headed to where he’d pointed. I followed him as he made his way to a small piano that was missing a front panel.

“Here, I’ll show you,” he said.

I stepped up to look at what he’d said was the action, but to me it looked like just a lot of unfamiliar parts. They repeated over and over again in a line, rows of wooden pieces with soft, padded heads on each one.

Standing closely, he reached over in front of me and pushed down on a piano key. He pushed down again on another key. “Do you notice something?” he asked.

I saw one of the wooden pieces moving with each push of a key.

“Wow, that’s some impressive engineering,” I said.

“Yes, pianos are really intricate machines. They can have up to 11,000 parts, so you can imagine how complicated it can be to repair them.”

Continuing and pointing toward one of the pieces resembling a large, padded cotton swab, he said, “This is what’s called a hammer. A piano has eighty-eight of these, each one corresponding to the eighty-eight keys. When a key is pushed, the hammer lifts, hitting the string and creating sound.”

I always like to say that my hands are my eyes.

“What made you decide to attend piano repair school?” I asked.

“I’ve always loved working with my hands, and this seemed like a natural next step for me.”

He turned his hands upward, showing me his palms.

“Oh, cool!” I immediately noticed a tattoo on his left hand and softly touched his skin where I saw slightly faded ink. The tattoo was of an eye, staring out at me from his palm.

“Yeah, I’ve had this for twelve years. I always like to say that my hands are my eyes.”

To be precise, the tattoo is the Eye of Horus, an ancient Egyptian symbol that represents healing and protection. In retrospect, it was one of the many things that initially attracted me to John. I’d later tell him that, when I first saw it, I could tell he was a bit of a recovering “bad boy,” which wasn’t necessarily a deterrent. He got it when he was eighteen, partially as an act of rebellion, and partially because he’s always loved Egyptian symbology and art, along with their long history and culture. It has become a reminder to himself of how important his hands are to him, as they allow him to see the world and practice his craft. His sharing of the tattoo’s meaning on the first day we met was the beginning of my lessons on blindness. I’d never considered how important a blind person’s hands are to them until that moment.

After chatting for a bit, John and I got to work on our respective projects on opposite sides of the classroom. “The Piano Hospital,” or the Emil Fries School of Piano Technology for the Blind of Vancouver, Washington, had been around since the 1940s. It was a place where blind and low-vision students could learn how to tune pianos and repair the instruments.

The fundraiser I was part of was called “Keys to the City.” The idea was that local artists would paint pianos, and they would be placed around the city in public for people in the community to play. The pianos would be sponsored by local businesses, funds from which would benefit the school.

For this project, I’d be working with a group of teens from a local homeless shelter to decorate the piano after I primed it. I’d do the primer, and they would add paper collage elements after it dried. We’d met earlier that week to have a group vote on what the theme of the piano would be. They chose “love” and decided they would each create hearts with poems and drawings that would cover the instrument.

As I was priming the wooden surface, I heard a robotic female voice coming from John’s side of the classroom. I looked over and saw him tapping and swiping at the screen of his phone. I listened as the voice from his phone read a list of songs to him. I realized it was an adaptive technology program for the blind. After a couple minutes of more tapping on his phone screen, music began playing softly from the device.

My eyes widened as he turned up the volume. “Big Yellow Taxi” echoed through the classroom, and I heard him softly singing the lyrics as he trimmed the ribbon-like ends of the bridle straps.

“I love Joni!” I said. In fact, Joni Mitchell was my favorite musician.

He smiled. “Me too. Honestly, I think I only know this one song of hers, but it’s a great one.”

We both started singing in unison as we worked. It felt silly and perfect.

. . . they paved paradise . . . put up a parking lot . . .

As the day went on, he played more of the music on his playlists, and we chatted. I learned he had moved to Vancouver, Washington—my hometown, where I was born and raised—from Utah, where he lived with his parents before moving to the city along the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest.

John said he had been born in Craig, Colorado, moved to Wyoming as a teenager, and moved several more times after that. The large family relocated often because of his father’s job as an electrician in the mining industry. They ended up in Salt Lake City, where he lived for a short while until he ventured off on his own and went back to Colorado. He ended up back in Utah with his folks before making the move farther west to attend the piano school.

For my own part, in addition to being a painter, I was also a photographer and never went anywhere without my camera. I knew the moment I saw John I wanted to photograph him. I decided to take a short break from painting the piano and worked up the nerve to ask if he would mind me photographing him while he worked.

I took out my camera and started snapping some quick shots. I didn’t want to distract him from his work too much. I felt a little sad, realizing he wouldn’t be able to see the finished photos.

My priming work on the piano was done and I lingered, slowly cleaning up my workspace. I finally got up the courage to ask him if he planned on returning anytime that week. The answer was yes, he’d be there most days.

I gathered my things and wished him a good night and told him I’d probably see him later.

“See you later.” He grinned widely, and I could tell he made this wholesome joke often.

A couple days passed after my first meeting with John. I was excited to go back to the school. While I was, of course, looking forward to continuing my work with the fundraiser, a lot of my excitement stemmed from hoping I’d run into John again.

The kids from the shelter who were going to work on the piano with me were set to show up soon. I shuffled quickly into the school, my arms full of supplies, and saw that a friend had dropped off pizzas for me to share with the teens while they worked. I glanced around, but John was nowhere to be found. I tried not to focus too much on my disappointment and decided to think about how much I was looking forward to spending time with the group of kids I’d grown so fond of. My attention turned toward the faint giggling and murmurs from the teens coming down the hall. Their laughter echoed off the old, tiled walls.

I leapt up from kneeling near the piano and turned around to greet them. My arms stretched out, I exclaimed, “We have pizza!”

A couple of them rushed up to me and gave me fist bumps and high-fives. After a bit of chatter, the kids all grabbed some pizza, taking it with them to just outside the classroom where I’d met John a couple days earlier, and sat cross-legged in a circle as they ate. I was inside the classroom, concentrating on sorting the various decorated hearts they had made. They planned to glue the hearts to the painted surface of the piano, then apply a layer of decoupage over them. Ruminating on their chosen theme, I smiled and wondered again if I’d run into John.

That second day I spent with John hadn’t been full of any real conversation. But, combined with the company of the young group and him playing DJ for us, it had been a good day, and one I didn’t want to forget.

Then I heard some faint apologies and the sound of people moving around outside the door. I peeked out and there he was, trying to navigate the obstacle course of young adults scattered about the hallway. Good-naturedly, he smiled and said to the kids, “No worries, just watch out for my cane. I wouldn’t want to accidentally git you with it.” His Western cowboy accent was strong today. It struck me at that moment how old his soul seemed.

I backed up as he approached the doorway to the classroom. “Hello, it’s Anni here!” I said.

Turning in my direction, he stopped and stood with his white cane next to him. The cane was almost five feet in height.

“Howdy,” he said. “How is your project coming along?”

“Pretty well, the kids are here, as you probably noticed, and they are going to work on decorating the piano today. We’ll try to stay out of your way. Sorry about that.”

“Oh no, it’s okay. I just need my small corner over there and I’m all set.”

I walked back out into the hall and saw the kids were finished eating and were getting antsy to start working. We crammed into the classroom, trying not to get in John’s way.

He started playing upbeat music from his phone and the teens seemed to appreciate it, joking around with each other as they added hearts to the piano’s surface.

Later, after the kids had left, and as I gathered my things to leave, I got up the courage to ask him a question. “There is a sculpture garden nearby with a lot of tactile art in it. Would you want to go check it out with me sometime?”

“Sure, that sounds fun,” he said, showing another warm smile. “I haven’t gotten to check out the city much since I moved here last year. I’ve been mostly attending school, or I guess just hanging out with my friends at the apartment building where I live. Here, I’ll give you my number.”

That second day I spent with John hadn’t been full of any real conversation. But, combined with the company of the young group and him playing DJ for us, it had been a good day, and one I didn’t want to forget.

A couple days later, I realized I had left a small box of supplies at the school. I took this as an opportunity to go there and possibly run into John again.

My heart was racing when I pulled up to the school. I took a deep breath and put my hand on the front door. It was locked. Oh well, I thought. I’ll give them a call this week to schedule a time to retrieve the rest of the supplies.

On my way back home, I felt a surge of bravery and had an overwhelming urge to call John. Resolute, I pulled into the parking lot of a national park along my way. I knew it would be a quiet place where I could gather my thoughts. I parked my car and started dialing John’s phone number, which I had written on a piece of scrap paper. After a few rings, he picked up.

“Hi, it’s Anni . . . the piano painter,” I said. I felt so awkward.

“Oh hi, how’s it going?” John said.

“Good, I was wondering if you’d like to hang out tonight?”

There was silence, followed by what sounded like his hand covering the speaker.

“Hey, can I call you back in a little bit?” he asked.

I felt completely deflated, believing this meant he was in no way interested and was just trying to find a good way to let me down. I put the car in gear, pulled out of the parking lot, and drove in silence the rest of the way home.

I was sitting on my couch about an hour later, still feeling a bit sad, when he called me back and asked if I wanted to pick him up and go harvest peas in his community garden plot. It sounded like an activity I’d enjoy, and I quickly agreed!

Later, I learned from John that his hesitant response had been due to the fact that he was short on funds, or as he put it, “broke as a joke.” He’d been trying to think of an activity that would cost nothing. If my nerves hadn’t gotten the best of me when I’d called, I wouldn’t have forgotten to suggest the sculpture garden again, perhaps saving us both a bit of stress. I think, though, it worked out as it should have, as John’s garden would become an important part of our story.

A few hours later, I stood outside of John’s door, shaking slightly from nerves. I knocked softly and heard shuffling inside. He opened the door, and I could see it was totally dark inside his apartment.

I was startled by the dim room at first, and then remembered he didn’t have the need for light.

“Hey, let me just grab my cane,” he said.

“My car is parked right here in front of your place. Do you need me to help you get to the door?”

“I got it, thanks.” He found the car with his cane swooping back and forth, and then followed the back of the car, using the trunk as a landmark. He moved around to the front passenger door, where he easily found the handle.

On our way to the garden, my curiosity piqued, and I asked him some questions that had been brewing in my mind.

“Do you mind if I ask about your blindness? I don’t want to pry if it’s too personal.”

“Ask away! I’m used to people asking. It’s really no trouble.” He smiled, his eyes closed as usual. I thought he looked so peaceful with his eyes closed.

“Okay. Are your eyes shut by choice?” I asked.

“No, I have permanent nerve damage in my eyelids and don’t have control over opening them. They are closed all the time because of that. But it’s honestly easier for me this way, since I’m totally blind.”

“Oh, that was my next question, whether or not you were totally blind. I’m so surprised with how well you get around and how independent you are.”

“I’m lucky I have really good spatial awareness, plus I went through mobility and white cane training after I became blind.”

I wondered what had caused his blindness, since he had mentioned nerve damage. It felt too early to ask about this, so I refrained. I was hoping there would be plenty more time to get to know him and learn about what had caused his condition.

We pulled up to the abundant community garden, full of greenery. I saw that this was a busy time of day. Couples, families, and solo gardeners dotted the lush landscape. Some wore broad-brimmed hats, some watered their spaces with hoses.

John easily found the garden plot and I shook my head at this, smiling in amazement. There were dozens of patches divided by wooden stakes, but he found his own spot pretty quickly. He told me he shared the plot with a good friend of his, and they were both really interested in gardening.

The peas weren’t growing upward on trellises like I was used to seeing. These were growing in a hedge pattern closer to the ground. He had put stakes all around the plot and strung twine around the posts in an almost spiderweb pattern. I noticed the stakes were made of old piano keys. He told me this was a way he was able to differentiate his plot from the others. I could see there was a great bounty of green peas, bouncing on the vine as he felt around the patch. Their little spirals seemed to dance as he patted the greenery, inspecting it with his hands.

I could see that I just needed to jump in and start picking. We had brought some plastic containers, and I laid one near to where he was stooping. I told him it was there so he wouldn’t trip on it.

I slipped my sandals off my feet and leaned down to start harvesting. I kept peeking up at him, wondering if his quietness was because he was nervous or if it was just in his nature. I realized I knew very little about him. Later, I would find out that John was very laid back. As in, he was in his own world kind of laid back, and I needn’t worry about it. It was just who he was.

Judging from the fact that I had been the one to ask him for his number first, I decided that I needed to be the one to guide our conversation. Honestly, I wasn’t very good with silences, which was odd because I wasn’t exactly the most talkative person. I could carry on a conversation well enough, but with an introverted nature, I leaned toward the quiet side myself.

This felt different, though. I felt drawn to know him. He intrigued me in a way I couldn’t quite pinpoint. I guess the blindness had something to do with it, but it was something else, too. He had a peace about him that I envied. My anxious nature didn’t often find the tranquility that appeared to come so naturally to him.

Out of nowhere, he started talking about the pattern of the peas and what had made him decide to try this method of growing them. With his Western drawl, and the way he talked, I was reminded of someone from another era. I pictured him as a farmer in overalls in the 1930s, proudly sharing his gardening secrets with a neighbor. I blushed when I realized I was getting distracted by the daydream and brought my attention back to his demonstration.

I realized John was quite talkative, it just took the right subject.

After a bit, I helped him track down a nearby hose. He watered the pea patch, that same peaceful look on his face.

Though it was perhaps an atypical first date, harvesting peas in John’s pea patch was perfect for us, and the site continued to be instrumental in our relationship.

We chatted more about gardening, and after an hour, he suggested we sit in the grass and relax a bit.

John walked toward an open spot on the ground, slightly stooped over with his cane in front of him as he swept his arm back and forth. He looked like a wizard performing a magic spell, and I was tickled with how cute it was. I realized he was making sure there wasn’t a shrub or low tree as he sat down. I noticed John had a definitive hump at the top part of his back. Later, we would jokingly call this his “stegosaurus hump,” and I would learn it was a result of some serious back injuries he’d accrued over the years.

Cross-legged and sitting on the soft ground, I covered my legs with my skirt and leaned my elbows forward onto my knees. I pulled at the grass, nervously yanking at it and making a little pile of the green blades in front of me.

He pulled out a pack of cigarettes, and I felt a mix of disappointment and nostalgia. I had been a smoker for eighteen years and had quit just the year before, when I was thirty-four. I was worried his smoking might tempt me, but once I smelled the smoke, I knew it wouldn’t be an issue. I watched as he held his lighter slowly to the end, careful not to burn himself and trying to feel the end of the cigarette with his other hand. It was fascinating to watch, but I felt myself staring again. I felt my cheeks light up in embarrassment and felt guilty for being grateful he couldn’t see me blushing. I both loved and hated the smell of tobacco. It was what John would later tell me he called a “good/bad” smell. That was the perfect descriptor. It was stinky, but in a strangely comforting way.

I built up the courage to ask him something I had wanted to ask since we met that first day.

“I’ve been wanting to ask you this, but feel silly. Do you even know what I look like?” I laughed awkwardly.

John’s grin widened and two heart-melting dimples appeared.

“I don’t know exactly what you look like, but if you’d like to tell me, I’d love that. I did ask my friend and she said you are ‘one hot mama.’” The friend in question was another artist who was painting a piano at the school, and she’d seen me around there.

Blood rushed to my cheeks, and I giggled at the thought of me being called such a name. I was more librarian than rockstar, but I decided I would take the compliment. I silently thanked this friend of his for the accolades. It was also the moment that I knew we were on a date. No mere friend zone here. Good!

“Well, I’m on the round side, and I wear glasses,” I said, thinking it could be helpful to provide more concrete details. “I have gray-blue eyes and light brown hair with reddish tones, and I’m a shorty, only 5'2". I dress a bit like a schoolteacher; I love wearing long skirts and cardigans.”

“Oh good, there’s more of you to love,” he said, referring to the comment in which I alluded to being on the larger side.

My eyes widened, and a goofy grin appeared on my face. Oh, man, this guy was precious.

“Honestly, I had pictured you in a very specific outfit. The first time I met you I imagined you wore a blue dress, like an old-fashioned German dress you’d see in Heidi or something.”

“Wow, that’s quite wholesome! I like it.” My grin got even bigger, and my cheeks reddened.

We talked about how much he liked the piano school and what his favorite things about the Pacific Northwest were. He said the school was a life-changing opportunity for him and it was challenging work, which he was grateful for. He said it kept him focused and gave him a sense of purpose. He told me that he’d always loved working with his hands and even had a certification for small-engine repair.

He said his father had started teaching him to work on cars when he was young, which made mechanics a lifelong hobby for him. In my mind, I imagined he could probably change the oil in an engine but didn’t think he could do anything more advanced than that. Later, I would be proven very wrong. I soon learned that John was used to people making assumptions and doubting him, which, thankfully, I eventually stopped doing. It was something I wasn’t proud of, but I’ve always been open to learning and letting go of my presumptions.

As he spoke, I noticed some scars on his face, one at his hairline that spanned his entire forehead. The hair along that scar was slightly sparse, it almost looked like he had hair plugs, but I didn’t notice this until I was very close. I assumed the hair growth pattern was from whatever had caused the scar. There was also a scar shaped like a lightning bolt on his left temple and a round one on the right temple. I saw some bumps I couldn’t quite identify in a couple places above his eyebrows. I held myself back from asking about them. That seemed like a second- or even a third-date-type question.

He went on to tell me about his large family, two sisters and three brothers. John was the baby. I told him about my two sisters, I was the middle kid. I told him I had been born and raised in Washington state. I asked him if he planned on moving back to Salt Lake after graduating from the piano school.

“Oh, definitely not, I plan on staying right here. The moment I got off that plane I knew that I was home. My friend Bud originally told me about the Pacific Northwest, and the way he spoke about it sounded almost magical. I had to check it out for myself.”

I was relieved he didn’t have plans to leave. I had every intention of staying put in Washington. I had planted my roots, and believed my roots were there for good.

John talked about not being able to see the trees, but still knowing they were there all around. Our area of Washington, like most of the state, was lush with trees. Trees and wood were eventually going to be a huge part of our lives, though I didn’t know it yet.