2,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

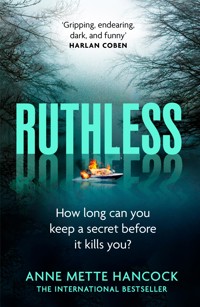

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Kaldan and Schäfer Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

'Gripping, endearing, dark, and funny ... Highly recommended' Harlan Coben When 10-year-old Lukas disappears, investigator Erik Schäfer has little to work with. Until he discovers that the boy is obsessed with pareidolia – the psychological phenomenon where we see faces in random things – and has recently photographed an old barn door. Journalist Heloise Kaldan thinks she recognizes the barn – but from where? Kaldan drops her current article, a controversial investigation into soldiers with PTSD, to cover the story of the missing boy. But when she realises that the traumatized soldiers are mixed up in Lukas' case, Schäfer and Heloise must try to separate optical illusion from reality – before it's too late.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

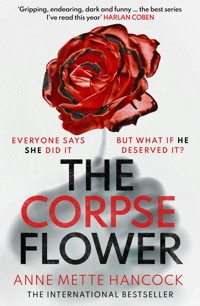

ALSO BY ANNE METTE HANCOCK

The Corpse Flower

SWIFT PRESS

First published in English in the United States of America by Crooked Lane Books 2022 First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2023 Originally published in Denmark by Lindhardt & Ringhof 2018

Copyright © Anne Mette Hancock 2018

The right of Anne Mette Hancock to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800751514 eISBN: 9781800751521

To Vega and Castor You were written in the stars.

C H A P T E R

1

THE MAN MOVED quickly, sliding past the bushes and the bare trees. The February wind seemed to come from all sides at once, feeling like thousands of little needles hitting his cheeks. He pulled at the strings on his hood so that it tightened around his face and he looked around.

There were no joggers or dog walkers out today on the grounds of Kastellet, the old seventeenth-century Citadel. The temperature had been like a buoy in the water for days, bobbing steadily up and down around the freezing point, and the strong wind made it feel like the harshest winter in decades. Copenhagen seemed deserted in the cold, like a ghost town.

The man stopped and listened.

Nothing.

No sirens to break the controlled rumble of the city, no flashing blue lights out there in the twilight.

He walked up to the top of the fortress’s old earthwork rampart and looked over at the entrance to the grounds by the parking lot at Café Toldboden and Maersk’s headquarters. He wrinkled his brows when he saw that the parking lot was empty, then looked at his watch.

Where the hell are they?

The man pulled a cigarette out of a pack in his inside pocket and squatted down in the lee of one of the cannons. He tried to light his lighter, but his hands were yellow from the cold and felt dead. He extended and bent his fingers a couple of times to get the circulation going and noticed the blood spot, a small, coagulated half-moon of purplish black substance under the tip of the fingernail on his index finger.

He made a half-hearted attempt to scrape out the congealed substance, then gave up and got his lighter lit. As soon as the fire caught, he thrust his hands back into his pockets and held the cigarette squeezed tightly between his lips as he paced back and forth on the rampart, impatiently eyeing the parking lot.

Come on, damn it!

He didn’t like waiting. It always made him feel restless and gave him a twitchy feeling in his gut. He preferred to keep busy, constantly in motion. Silence meant time for reflection and made his thoughts wander back to a smoke so thick that he had to feel his way past the dead, mangled bodies, back to the blood running out of his eyes, down his cheeks, and to the silence, the deafening silence that followed the blast, when those who were able crawled out of the dusty darkness and gathered in front of the destroyed building.

Paralyzed. In shock.

If only he could shake those images, release them like a bouquet of helium balloons and watch them float away, dancing in the sky until they were out of sight.

The man looked down at the café again and spotted the silvery gray Audi pull up in front of the building and stop. The engine was on, its exhaust warm and steamy in the cold. A single blink of the high beams told him that the coast was clear.

Finally!

He started walking down toward the car, but halfway down the earthwork, he spotted something that made him slow his pace. He scrunched up his eyes and focused on the pedestrian bridge over the moat that surrounded the Citadel.

Then he came to a complete stop.

There was a figure standing in the middle of the bridge, almost camouflaged by the twilight, a hooded person wearing an orange backpack.

It was the strange, bent-over posture of the figure that had made him slow down. But it was the child the person was holding that had made him stop.

A boy he estimated to be eight or nine years old hung limply over the side of the bridge while the person with the backpack held the fabric on the shoulders of the boy’s down jacket. The person was yelling, but the wind snatched up the words, punching holes in them, so he couldn’t hear what was being said.

He looked over at the car again and saw yet another insistent blink of the headlights. He needed to hurry now, but . . .

He looked down at the bridge again.

Then the figure let go of the boy.

C H A P T E R

2

THE CLINIC ENTRANCE was through the back side of an ivy-covered building that leaned curiously against the wall around Frederik VIII’s palace. From the window of the waiting room, Heloise Kaldan could see the top of the Marble Church’s frost-stained dome and the guards in the palace square, who were parading back and forth in front of Amalienborg Palace like loose-limbed sleepwalkers in a snow globe.

She reached for a fashion magazine and swung one foot back and forth nervously as she browsed through it. Adrenaline tingled at the ends of her nerves, and her eyes roved absentmindedly over the fashion reports and articles about skin care regimens. Shallowness and the glorification of teenage anorexia, wrapped up in pastel colors.

Who the hell reads this garbage?

She tossed the magazine aside and looked around the waiting room.

The whole room looked like something right out of some Californian interior design magazine. It was decorated in white and cognac-colored hues, punctuated only by succulents in oversized clay pots. The walls were adorned with posters and lithographs of all shapes and sizes, hung so closely together that you could just barely glimpse the asphalt-colored wall behind them. The floor was covered with a cream-colored Berber rug, which tied the room together in one final stylish touch. The whole thing was so delightful that you’d almost be able to forget why you were there.

Almost . . .

There were two other patients in the waiting room: a gaunt, elderly man and a young girl with milk-white skin and big silvery gray eyes. Heloise estimated her age to be no more than eighteen and hoped that the girl had come to the clinic for some purpose other than her own.

A tall, blond man in white canvas pants and a mint-green T-shirt stuck his head into the room and the girl across from Heloise immediately sat up straighter in her chair. She inhaled oddly through her nose, moistened her lips, and tried to make them seem fuller by half-opening her mouth into a pout. The expression left her looking like she had just detected some objectionable odor in the room.

Selfie face, Heloise thought. One of the era’s oddest inventions.

The man in the doorway swept a lock of hair out of his eyes with a toss of his head and then nodded to Heloise.

“Heloise?”

She stood up.

She just had to get it over with now.

* * *

The doctor showed her into the exam room with a motion of his arm. He read her records on the computer screen and then looked at Heloise.

“So, Heloise . . . You’re pregnant?”

He mispronounced her name. The hard “H” made her name sound harsh, like an effort. Heloise had corrected him at every appointment for the last four years. This time she let it go. Instead she said, “Yes, so it would appear.”

“Have you ever been pregnant before?”

She shook her head and showed him the test, which she had brought in her purse. There were two red lines inside the plastic window in the middle of the stick. One was very clear, the other a misty watercolor, weak like the beginning of a rainbow that you could see best by not looking at it directly.

The doctor looked at the test and nodded.

“Yes, it looks positive. And am I to understand that this doesn’t suit you well?”

“It wasn’t part of my plan, no.”

He nodded and sat down behind his white-lacquered desk.

“No, well, that happens, I guess.”

Heloise sat down on the other side of the desk and set her purse on the old parquet flooring. The floor was like the rest of the building, strangely bowed and crackled like an old soup tureen, and made the chair rock under her.

The doctor smiled warmly to emphasize that she could speak openly. Dimples bored into his cheeks, like fingers in soft clay, and his blue eyes looked boldly into Heloise’s. It had taken her a couple of years to discover that his magnetic charisma and forward eye contact were not reserved only for her. He was not flirting. He was just genuinely interested in her health. Plus, the gleam of his blue-green eyes was competing with the wreath of polished white gold that ran around his left ring finger.

“According to the information you provided when you called this morning, you’re about five weeks along. Is that correct?”

Heloise looked down and nodded. That was what the calculator said on the due date website she had found online.

“That’s good,” he said. “The thing is, a medical abortion is only possible during the first seven weeks of a pregnancy. From eight to twelve weeks, the only option is a clinical termination of the pregnancy.”

Heloise glanced up again. “Which would involve hospitalization?”

“Yes. It’s a quick procedure, but nonetheless it’s always preferable to avoid anesthesia. So instead you’ll get this . . .”

He handed Heloise a single pill from a package that said Mifegyne in green letters.

“You’ll take this once we’ve confirmed your due date, and that will effectively terminate your pregnancy.”

He turned his chair halfway around and typed a few lines into the computer in front of him.

“I’ll also write you a prescription for fifty milligrams of Diclon, which is a muscle relaxant, and a medication called Cytotec.”

Heloise’s heart began beating in a strangely irregular rhythm as he spoke.

That will effectively terminate your pregnancy . . .

What the hell was she doing? How had she ended up here?

“It shouldn’t take more than a few hours, and for the most part it’s pretty undramatic,” the doctor continued. “But it’s still best if you set aside a whole day for it and have someone around while it’s going on. Are you seeing someone right now who can look after you?”

Heloise shook her head. “Yes and no. It’s . . . complicated.”

The doctor pursed his lips and nodded in understanding.

“This kind of thing generally is. It’s a tough situation for most people.”

Heloise looked down at the pill in her hand and thought about Martin.

She knew he would be excited about the idea of a baby, happy and far too hopeful, and it would force their relationship into the next phase. He would insist on taking a Neil Armstrong–sized step forward, whereas she would want to take three steps back.

Heloise preferred things the way they were. Or to be more precise, the way they had been. Their relationship was fun and comfortable and—most of all—still fairly casual. But now, from one day to the next, it felt as if there was a ticking time bomb between them. The countdown had begun with those two lines on the pregnancy test, and Heloise could see red digital numbers blinking like a doomsday clock in her mind’s eye. It was going to explode whether she cut the red or the blue wire, she knew that.

She might as well get it over with.

The doctor studied Heloise intently, as if he were trying to decode her inexpressive body language.

“If you’re having any doubts, it’s no problem to wait—”

“I’m not having any doubts.”

“Okay, well then why don’t we just see how far along you are?”

He pointed toward the exam table with his chin and put on a pair of steel-colored acetate glasses. The lenses looked curiously small on his square face.

“A home pregnancy test like that can be a little off, so we’ll just confirm that you’re on the right side of the eight-week mark.”

Heloise took a deep breath and took off her leather jacket.

* * *

The silence in the room was broken only by the ticking of the clock above the table and by the doctor’s calm breathing.

Heloise was holding her breath.

She lay with her face turned away from the monitor, away from the scanning images she was afraid she would never be able to erase from her mind again if she caught so much as a glimpse of them. She had tried all week to avoid imagining what was in there, but she had slept fitfully at night, tossing and turning, her sheets wet from sweat, seeing little arms and legs in her dreams. Fingers and toes. A head covered in brown curls.

But no face.

Each time there had been only a featureless circle at the top of the neck. A concave surface, without any further form or color, like a baby with a dinner plate where the face should have been.

What did that mean?

That she didn’t want to pass on Martin’s genes? That she was terrified by the thought of passing on her own?

She couldn’t stop speculating about whether there were hereditary variants of evil, whether a rottenness could hide in a person’s blood, like a sleeping cell, that could skip a generation or two. In any case, that was not an experiment she wanted to conduct.

“All right, Heloise,” the doctor said. “As it turns out, the test was accurate.”

Heloise reluctantly looked up.

“Here’s your bladder and your stomach.” The doctor pointed at the screen in front of him, where a vague black and white shape filled the screen. “And there, that’s your uterus. Do you see?”

Heloise tilted her head and stared blankly at the splotch in front of her. It could have been an ultrasound scan of anything: a human brain, a cow’s stomach, Jupiter! She wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference.

He drew a circle on the screen with his finger around a little peanut-shaped spot.

“There. You see? It looks like you’re right around five weeks—give or take a day or two.”

Heloise nodded and looked away.

“Are you okay?” he asked, turning off the monitor. “Your mind is made up?”

“Yes.” She raised herself up a little on her elbows. “But there’s actually something else I’d like to ask you about. I’ve been having this uncomfortable trembly feeling for a while now.”

The doctor pulled off his latex glove with a talcum-powdery snap and nodded for her to continue.

“Can you try to describe it in a little more detail?”

“I don’t know how to explain it. It’s just something that feels . . . off. A weird fog around me, as I’m looking at the world through a glass dome, and my head is teeming with thoughts. It’s gone on for a long time now, I think. Several months, long before this.” She nodded at her belly.

The doctor removed his glasses from his nose with a pincer grip and cleaned them on his T-shirt as he studied Heloise.

“You said a trembly feeling? Do you mean a type of uneasiness?”

“Yes.”

“Pressure in your chest? Palpitations?”

She nodded.

“What are you doing professionally these days, Heloise?” Still that harsh H sound. “You’re a journalist, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“So, does your job keep you fairly busy?”

“Well, I suppose so.”

“Do you bring work home with you?”

“Doesn’t everyone these days?” Heloise said with a shrug.

He crossed his arms and bit his lower lip as he regarded her. “It sounds like you might be under some pressure. Have you been through a particularly stressful period recently?”

Heloise noticed a tingling in her temples as the memories bubbled up inside her like foul-smelling methane gas in a swamp: Hands tightening around her throat. Children with closed eyes. The engraving on her father’s headstone . . .

Memories that had left Heloise’s heart blue-black with cold.

A particularly stressful period?

“You could say that,” she said, sitting up.

“They sound stress-related, your symptoms,” the doctor said. “But I’d like to get you tested for hypothyroidism, so why don’t we just take a blood test to be on the safe side—”

They were interrupted by two quick knocks on the door. Without waiting, the elderly receptionist stuck her made-up face into the room.

“I’m sorry to bother you, Jens, but there’s a call for you.” She pointed to the phone on a light Wegner table at the other end of the room. “It’s from the school’s office. They say it’s important.”

The doctor furrowed his brow, and a vertical line appeared above the bridge of his nose.

“I’m sorry,” he said, turning to Heloise and smiling, mildly embarrassed. “Do you mind if I just . . .”

“No, of course not,” Heloise said, waving his question away.

He closed the frosted glass sliding door that divided the room, and Heloise could hear him walking rapidly over to the phone.

She looked down at the pill she was still holding in her hand. It had grown damp from her sweat and some of the color had come off onto the palm of her hand, filling her lifeline with a white powdery mass. She set the pill down on a small stainless-steel tray and half listened as the doctor answered the call behind the sliding glass door.

“Hello? Yes, it’s me. Why, yes, he should be. What time is it, did you say? Well then, he got out twenty minutes ago and he’s probably on his way downstairs. He has certainly been known to take his own sweet time at that kind of thing . . . Well, maybe he went straight to the playground with Patrick from the rec center. I know that they were going to get together today. Have you checked there?”

Heloise got up and put on her pants and her leather jacket.

“No, he’s not,” the doctor continued. “No, he wasn’t picked up. I’m positive about that because my wife is supposed to pick him up today and she’s still at work and . . . Yes, but I can’t . . . Okay. Yes, okay. I’m on my way now!”

Heloise heard him hang up and dial a number on the phone.

“Hi, it’s Dad. Where are you? Give me a call when you get this message!”

And then another call.

“It’s me. Did you pick up Lukas? . . . They just called from the rec center, and he hasn’t shown up there after school.”

Heloise could hear the increasing panic take hold of his voice and squeeze. She turned to look at the framed photo on the windowsill. The doctor looked younger in the picture than he did now, but Heloise could recognize his kind eyes and pronounced jaw line. He had his arm around a pretty woman with dirty blond hair, who was wearing a yellow sun dress with spaghetti straps over tan skin, and standing between them was a child who looked to be about three or four years old, excitedly waving an Italian flag.

“I’m heading over there now,” came the voice from behind the sliding door. “Yes, but let’s just take it easy. He’s gotta be there somewhere.”

The fear churning in his voice emphasized to Heloise that she never wanted to live like that, in fear. The responsibility a child would entail. The vulnerability that would impinge on her life.

Better to feel nothing.

She picked up the pill from the metal tray, folded it into a paper towel and stuck it into her pocket.

Then she slung her purse over her shoulder and left the clinic.

C H A P T E R

3

THE WAIL of the smoke alarm yanked detective Erik Schäfer out of the reverie he had fallen into at the kitchen sink.

He smacked the alarm with a fist the size of a pomelo and turned off the toaster. The disappointing scent of cold plastic welcomed him when he opened the fridge, and he stared at the half-empty shelves, unimpressed.

There was nothing in there besides a container of butter, a jar of marmalade, and a liter of whole milk that he and Connie had bought at 7-Eleven after they had landed at Copenhagen Airport last night.

He set the items out on the kitchen table and pulled his vibrating phone out of his back pocket. It was Lisa Augustin, his partner from the Violent Crimes Unit, calling.

“Yup. Hello?”

“Hi, it’s me.” Augustin’s voice sounded chipper and far too loud.

Schäfer made a face and pulled the phone a little away from his ear.

“Good morning,” he muttered.

“Well, ‘good afternoon’ you mean. Jet-lagged?”

Schäfer grumbled noncommittally in response.

“How was your trip?”

“The trip was good,” he said, carefully extracting the charred bread from the toaster. “I was this close to not coming home again.”

He scraped the worst of the charring off the bread with a knife. The dark particles lingered in the air like volcanic dust and then silently drifted down onto the counter. It reminded him of the black sand beaches on Saint Lucia in the Caribbean, where he and Connie had spent the last five weeks in their vacation shack at Jalousie Beach. A ramshackle house painted a pale pink with white shutters and palm trees, yellow oleander, and mango trees in the backyard.

He missed it already.

They had been going to the island, where Connie had been born and raised, for the twenty-nine years they had known each other, and Schäfer was starting to prefer life there to his everyday life here in Copenhagen. Even so, there was always something that made him board the plane again to head back to Denmark. He told Connie every time that it wasn’t the job that drew him back, and then she smiled at him as if to say, yeah right. She loved him enough to let him spin the truth as he saw fit.

Lisa Augustin didn’t.

“Bullshit,” she said and laughed. “You missed me. Admit it!”

Schäfer ignored her comment.

“What do you want?” he asked.

“I just wanna know if you’re on your way?”

“I’m leaving in ten,” he said and took a bite of his toast. “See you at HQ.”

“No, that’s why I’m calling. I’m not at headquarters.”

“Where are you?”

“I’m on my way to the Nyholm School.”

“The Nyholm School?” Schäfer woke up. “What’s going on there?”

“There’s a kid missing.”

He closed his eyes tight. First day back and one of those cases?

“All right,” he said. “What do we know?”

“Not much yet, but as I understand it, the case involves a ten-year-old named Lukas Bjerre. He disappeared from the rec center that runs the school’s aftercare program at about two o’clock.”

Schäfer looked at the clock over the stove. It said 3:33 PM.

“Who’s with you?”

“No one. That’s why I’m calling.”

“What about Bro and Bertelsen? Where are they?”

“They’re investigating a death on Amerikakaj. And Clausen broke his collar bone, so I’ve been flying solo the last few days.”

“I’m on my way,” Schäfer said.

He hung up and took one sip of the coffee Connie had made for him before she had left for the store. It was lukewarm now.

He put his gun holster on over his shoulders in one quick motion and found his winter jacket.

On his way to the front hall, he glanced out at the patio in front of his little red brick house in Copenhagen’s pleasant Valby neighborhood. A sparrow landed on the birdhouse Connie had just decorated with little balls of birdfeed wrapped in light green mesh and was pecking at one of the fatty clumps of seeds.

Schäfer’s eyes scanned the tired winter lawn and stopped at the plastic yard furniture stacked in the corner of the yard, covered in dust and shriveled, rust-brown leaves. It was getting dark again already and he thought of the sun that was no doubt shining on a beautiful morning in Saint Lucia.

He shook his head as he stepped out into the cold.

“What the hell are we doing here?” he muttered, slamming the front door closed behind him.

C H A P T E R

4

HELOISE KALDAN AIMED the gun at the man at the big double desk in the middle of the room.

He sat as if in a trance, his eyes glued to the screen in front of him, hammering out a drum solo on the edge of the desk with his two stiff index fingers while the music poured out of the cell phone on the desk in front of him.

One hard strike on the hi-hat, as his left foot worked the pedal of an invisible bass drum.

Welcome to the jungle. We’ve got fun and games.

Heloise looked at the dark brown curls that covered his broad forehead and the white, freshly ironed shirt that was a little too tight around his muscular upper arms and chest.

She smiled at the sight.

Such a gifted man, she thought. So smart, so talented, and so extraordinarily vain.

She leaned farther in the doorway, silently, slowly, and put her finger on the trigger.

“Bøttger?”

“Hmm?”

Journalist Mogens Bøttger looked up from his computer the second the foam bullet hit his chest. An animal-like sound came out of his mouth, and he propelled himself backward in his office chair.

“What the hell?!”

He looked angrily up at Heloise, who was weeping with laughter, both hands on her knees. With the pill tucked safely in her pocket she felt light, almost cheerful. The day had started out so gloomily, and now it felt like she had an escape route. She could wipe the slate clean and start over.

Like dodging a bullet!

“You should have seen yourself,” she exclaimed, laughing.

“Kaldan, you . . . jerk!” Mogens complained and grabbed the right side of his chest. “That freaking hurt!”

“Oh, please!” Heloise blew the imaginary smoke off the muzzle of the fluorescent-green Nerf gun. “It’s a toy. How painful could it possibly be?”

“All right, give it here then!”

Mogens got up. At six foot eight, he towered over her. He tried to wrest the gun out of her hand.

“You’ll see how it feels!”

Heloise tossed the plastic gun away, toward the far end of the room, where it landed on an old, beat-up Chesterfield couch.

“Okay, okay, you win!” she said, holding both hands up in surrender.

Mogens reluctantly let go of her and sat back down in his desk chair, his facial expression childishly aggrieved.

“You look like one of the old men from The Muppet Show when you laugh, Kaldan. You know that?”

He made a goofy face and raised, then lowered his shoulders in a carefree caricature gesture, mimicking her silent laughter with a silly smile so big you could stuff a slice of watermelon in.

“That’s you, Kaldan! An old, laughing buffoon.”

Heloise smiled and sat down at her desk across from him.

He nodded toward the couch.

“Where’d you get the murder weapon from anyways?”

“It’s Kaj’s.”

Mogens’s eyebrow bent into a skeptical arch over his left eye.

“I’m sorry, what?” He turned down his music. “Did you say it’s Kaj’s?”

His surprise was well justified.

Kaj Clevin was an older gentleman with age spots who worked as a food critic for Demokratisk Dagblad. He was known for being a self-righteous snob who nursed a latent hatred of anything that might appeal to the proletariat, and his restaurant reviews were always narrowly targeted at the fraction of readers who shared his enthusiasm for what Heloise described as gastro-masturbation.

“What in the world would Kaj be doing with a neon-colored Nerf gun?” Mogens asked.

“He brought his grandson to work last week,” Heloise said with a shrug. “The kid must have forgotten it here.”

Mogens’s eyes widened.

“That ugly little monster with the underbite who was running around making a fuss in here the other day?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“That was Kaj’s grandson?”

Heloise nodded.

“Ugh,” he said, wrinkling his nose.

“I’m pretty sure you’re not allowed to say ugh about a kid.”

“Oh, I don’t give a shit. He looked like an orc!” Mogens jutted out his lower jaw, his eyes focused on some point in the distance. Then he turned his brown eyes to Heloise again and turned his palms upward. “Am I right?”

Heloise shrugged and started pulling notepads and work papers out of her black leather shoulder bag.

“I’m right,” Mogens said. “But to be fair to the young orc, there are exceptionally few kids who are actually charming. When I drop Fernanda off at day care in the mornings, they’re all sitting there with snot pouring out of their noses . . . absolutely beyond disgusting. Plus, they smell bad!”

“Don’t hold back, Bøttger. Come on, tell me what you really think.” Heloise smiled. She took out her phone and opened an email she had received from Morten Munk in the research department with the subject line Veterans vs. Background Population: Suicide Rate.

“If I can’t share this kind of thing with you, Kaldan, then who? You’re the only person I know who hasn’t been brainwashed. You remember my sister, right?”

“What about her?”

“She used to be such great company. She always had something exciting to contribute to the conversation, an interesting perspective. But then she met Niels, Nordea-Niels as they call him because of his job at the bank. And then they had kids, one of each—and okay, they’re very cute, they are. But now they’ve moved to Holte, where they bought a one-story house and an electric lawnmower with all the bells and whistles in terms of attachments and special features.”

“So what?”

“So now she’s just mind-numbingly boring.”

“But is she happy?”

“Of course she’s happy! But it really doesn’t suit her.”

Heloise suppressed a laugh.

“Well, then it’s a good thing that having a kid didn’t change you.” She eyed him sarcastically.

Mogens responded with an annoyed shake of his head.

“Of course you change, otherwise you’d be made of stone. But I have preserved my cynicism, and that is a darned important attribute in a person.” He emphasized his point with an insistent index finger.

“If you say so, Captain Haddock.”

“It’s true! Plus, it’s one of the reasons I like you so much, Kaldan. You’re one of the most cynical people I know.”

“Aw, that’s almost too kind of you.”

Mogens bowed his head in respect, as if he had just knighted her.

“Never change!” he urged.

“Don’t worry,” Heloise said wryly. “There’s no risk of that.”

She read the email from Morten Munk regarding what they had learned about suicide among veterans. Then she called Gerda, her best friend. It was her third try today. Gerda usually called her right back, and it rarely took more than an hour before she at least texted.

Today an unusual radio silence had prevailed.

“Hi, it’s me again. Please call me,” Heloise said after the beep. “I need your help with the article I told you about the other day.”

She ended the call just as the investigative team’s editor, Karen Aagaard, poked her head through the doorway.

“Where the hell is everyone?”

Heloise turned in her seat and looked toward the door. Then she smiled.

“Oh, hi! I thought you were out sick today.”

“I’m not sick. What’s going on? Where is everyone?” Karen peered critically at Heloise over the rim of her horn-rimmed frames and nodded over at the empty desks in the room. She was usually the department’s breezy motherly presence, but today she was giving off a surprisingly toxic vibe.

“I don’t know,” Heloise said, raising an eyebrow in surprise. Then she shrugged. “Out, I guess?”

“Editorial meeting. Now!” Karen barked.

Without another word, she turned on her heel, and you could hear her royal blue stilettos clicking, making a grouchy tsk-tsk-tsk sound all the way down the hallway to the meeting room.

Heloise and Mogens looked at each other.

Heloise shrugged and stood up.

“Are you coming?”

C H A P T E R

5

ERIK SCHÄFER SWITCHED off the siren as he passed the National Gallery. Word of the boy’s disappearance would spread soon enough, like lice at a Girl Scout camp, and the school’s parents would work themselves up into a foaming frenzy. There was no reason to accelerate the process.

He reached the school and parked his black, scratched-up Opel Astra half up on the sidewalk next to a statue of King Christian IV. His majesty peered at the school, which sat looking like a gigantic Monopoly hotel on a narrow strip between Østerport Station and the Royal Navy’s mustard-colored barracks.

The Nyholm School was to schools what the Marble Church was to churches, Schäfer thought. Not a dull avantgarde chapel with an organ whose pipes looked like the cylinders on an oil rig, but a place with a soul, with . . . spirit. He didn’t give a rat’s ass as to how many international awards the current era’s young star architects won or how many parades were held in their honor. They could build however many sustainable ski slopes, like the roof of CopenHill power plant, or however many eco-blah-blah buildings they wanted; Schäfer couldn’t stand all the glass constructions that had been popping up all over the city of late.

Sometimes he thought he must be the only person in all of Denmark who hadn’t been “drinking from the chamber pot,” a colloquial way of saying you’d lost your mind. Other times he figured he was starting to get old. Maybe both.

He scanned the schoolyard, where a crowd had now gathered in the twilight. Mothers and fathers stood in clusters, keeping their children on a tight leash, and even from far away he could decode their facial expressions. His efforts had been for naught. The lice were already starting to itch.

Schäfer spotted his partner of the last four years, Sergeant Lisa Augustin, as he passed the play court where a lanky, acne-ridden teenager was shooting hoops. Augustin stood with two uniformed officers, talking to a couple that—judging from their long, easy-to-read faces—Schäfer took to be the missing boy’s parents.

Aside from his height, the father resembled a young Robert Redford, Schäfer thought. Golden-blond hair, a pronounced nose, and a jaw that gave him an Old Hollywood sort of look. The woman at his side was also attractive but drowned out a bit in the crowd of mothers in the schoolyard—women who, like her, were wearing sensible shoes and coats that were appropriate for the weather. She looked practical and down to earth, a diametric opposite to Mr. Hollywood, but the look in her eyes stood out, Schäfer thought—a look of unmitigated horror.

Schäfer made eye contact with Lisa Augustin, and their reunion after five weeks apart was marked by a single nod.

She walked over to meet him, and when they reached each other, Schäfer asked, “Has he turned up?”

Augustin shook her head. Her blond hair was pulled into a tight knot on the back of her head.

“No, and it’s worse than I thought.”

“What do you mean?”

“The boy wasn’t in school today at all. No one knows where the hell he is.”

“What does that mean? When was he last seen?”

“This morning, here in the schoolyard. Witnesses saw him walk through that door there just before eight.”

She pointed to an old oak door behind them, one of the school’s two entrances off the schoolyard.

“But he didn’t show up in his classroom on the third floor when the first bell rang, so no one has seen him for . . .”—she looked at the TAG Heuer men’s watch that was strapped tightly around her sinewy wrist—“. . . for almost eight hours.”

“Eight hours?!” Schäfer repeated, the blood starting to tingle in his temples. “Why the hell didn’t the school react sooner?”

He looked around for a teacher or school employee, and his eyes fell on a middle-aged man leaning against the big climbing structure on the school’s playground. He was wearing a suit of armor made of spray-painted plastic, and the hilt of a foam sword stuck out under his one arm.

“His classroom teacher assumed the boy was out sick,” Augustin said. “Apparently there’s no procedure to check on absences during the day. That doesn’t happen until school gets out and they take attendance at aftercare.” She pointed with her thumb over her shoulder. “The Labyrinth—that’s what the aftercare program is called—is located here on the ground floor. Parents are supposed to notify them online if a child is sick, and if there’s an absence they weren’t notified about, then the teachers call and make sure the children were picked up or were out sick.”

“And?”

“And when the boy didn’t show up, they called the parents, who basically went into a coma, and now here we are.”

Augustin handed Schäfer a photo.

“This picture was taken at the beginning of the school year, but they say he has the same haircut and that he hasn’t changed much since August.”

The picture showed a boy with blond hair and thin lips, who looked curious, as if the flash had gone off right when he was asking a question. His blue eyes were wide and wary, his skin fair without seeming pale. He was a good-looking kid, Schäfer could tell. With those fine features and long, tangled eyelashes, he was pretty in a way that was usually reserved for girls.

“So that’s him,” Schäfer mumbled. He tucked the picture into the inside pocket of his bomber jacket and gazed up at the school building. “There must be hundreds of places in there to hide—attic, bathrooms, gym, storage rooms in the basement . . . We’ll need to search the whole thing. You said he went in here?”

Schäfer walked over and put his hand on the door handle, and it occurred to him that a school with old bones like this came with some inconvenient features. He had to put his full body weight into it to pull the oak door open.

Inside the entrance Augustin pointed to a large, two-lane, half-turn staircase, which ran along one side of the entrance hall.

“He usually goes up the stairs here to get to his classroom, but the back entrance to the school is right there. So he could basically have gone straight out there when he arrived this morning.” She nodded over at a door on the opposite side of the hall.

“You think he cut school?”

“It’s possible,” Augustin said, flinging up her hands.

Schäfer walked over and pushed open the door and immediately found himself out behind the school.

He looked around.

The Hotel Østerport was in front of him, a hideous, prison-like block of concrete. He walked to the left along the hotel until he came to an overgrown slope behind a chain link fence. The fence had been clipped open in several places, so gaping holes allowed free access to the slope, which led down to the train tracks behind the hotel. Østerport Station was located a little farther down the tracks.

Schäfer stepped through one of the holes and studied the area on the other side of the fence.

Could the boy have come through here? Could he have hopped onto a train or walked over into Østre Anlæg Park, which sat like a jungle on the other side of the transit station’s graffiti-painted walls?

Every train line in the city stopped at Østerport. There were departures headed for every corner of the world, and in eight hours the boy could have made it to Berlin, to Stockholm, or somewhere else entirely. They were too late getting started.

Way too late.

Schäfer’s thoughts were drowned out by a commuter rail S train, which pulled into the station, its squealing brakes ripping through the clear, frosty air. He walked back to Augustin with a finger in one ear.

“We need to search the whole school,” he said. “We need to obtain any surveillance footage from the hotel and down at the station and interview people in the area about whether they saw the boy during the day. Does he have a cell phone?”

“Yes.”

“Get it pinged right away so we can see if it’s on or off and where it was last used. The witnesses you’ve already spoken to will need to be formally questioned.” He pointed ahead of him. “Østre Anlæg Park is over there on the other side of the tracks. So we’ll need to pick that apart, too.”

“That’s a big area.”

“Yup, so we’d better hop to it!”

Augustin held her phone up to her ear and asked, “How many people should I ask Carstensen for?”

Per Carstensen was the commissioner, and he had been uncharacteristically generous with his people lately. After the government’s decision to have the military take over a range of policing roles, the Investigative Unit had had enough manpower available for most of their duties. It was like a waterfront mansion for newly rich rappers from Copenhagen’s west side: an unaccustomed luxury, which everyone in the unit was afraid of losing again. But it was only a matter of time before they were bombed back to the Stone Age.

“We need to get a whole major circus set up,” Schäfer said. “And tell them to bring the dogs. We need to find that kid now!”

Augustin nodded.

“Eight hours . . . ,” Schäfer said.

He and Augustin exchanged a look, and he could tell from the lines in her face that they were thinking the same thing.

“It’s getting dark now, and the temperature has dropped below freezing,” he said. “This is a total shit show.”

C H A P T E R

6

“WELL?”

Editor Karen Aagaard looked around the conference room. She was like a prison guard doing cell inspections—ready to search the contents, flip up mattresses, and investigate hollowed-out deodorant containers in pursuit of illegal drugs, weapons—anything that might result in a whipping in the courtyard and a trip to solitary.

“What are you working on?” Aagaard glanced at Mogens, who began with his standard arrogance.

“I’m working on a story that has Cavling Prize written all over it,” he said.

Aagaard snorted.

“Let’s just hear what you’ve got before we start engraving your name on the little brass nameplate.”

“I have three sources who say that all the crime statistics released by the last government were significantly manipulated.”

“Manipulated? In what way?”

“They were incomplete, to say the least. Important numbers that went before the judge were left out. When they realized how overrepresented immigrants were, they decided not to include them in the overall statistics. They were simply scared of the outcry it would have caused if the truth came out. So they intentionally left immigrants out of the cumulative statistics, which artificially lowered the percentage of criminals from other ethnic backgrounds—just like they did in Sweden. The results were completely airbrushed.”

“Who decided to do that?”

Mogens shrugged.

“It was indubitably done at the ministerial level, but the national police commissioner must have been involved in some form or another.”

“And what would the purpose of this have been?”

“Politics!” Mogens flung up his arms to emphasize the obvious. “As long as the majority of the population believe that the horror stories are nationalistic propaganda, then Mr. and Mrs. Middle of the Road will stay calm. They intentionally misled Danes to make the immigration situation appear less critical than it is.”

“What kind of sources do you have?” Karen asked.

“Two officers from Station City and one from Central Station. They say the fact that the numbers were skewed is common knowledge among the police. They’re also sick and tired of dealing with immigrant gangs and bullshit, so they want the actual numbers daylighted.”

“Are any of them willing to go on record?”

Mogens shook his head.

“No one dares to say squat. But I have the actual numbers here.”

He took a little black notebook and swung it in front of Aagaard like a pendulum.

“So the story will compare the published statistics with the actual numbers and then question why this kind of monkeying around with the numbers was orchestrated. The turd lies on the red side of the fence, politically speaking, so someone over there has some explaining to do, as does the national police commissioner.”

“Okay.” Aagaard nodded. Her stance had softened a little. “I don’t think this is going to win you any awards, but fine. Have at it!”

“Kaldan?” she said, turning to look at Heloise. “What’ve you got?”

“I’m gathering material for a story on post-traumatic stress syndrome in veterans with the working title ‘The War’s Delayed Victims,’” she said. “In the last month alone, three veterans with PTSD have committed suicide. That’s a pronounced increase compared with the same month over the last ten years.”

Karen Aagaard’s mouth dropped down her face.

Heloise hesitantly regarded her editor. Aagaard’s dark hair was pulled tightly back into a ponytail, and her pearl stud earrings were in their customary place as well. But something looked . . . off. Then it hit her that Aagaard wasn’t wearing any makeup. Heloise couldn’t remember ever having seen her editor without it. Her winter-pale skin and tired eyes surrounded by eyelashes so pale they seemed transparent made Karen Aagaard look like a corpse that had bled to death. To put it mildly, it wasn’t a flattering look.

Heloise blinked away those thoughts and held up her cell phone. She pointed to a text exchange she had had with Gerda earlier in the week.

“I have a friend who works for the military. Her name’s Gerda Bendix. She’s a trauma psychologist and of course she can’t say anything about personnel matters, but I know that one of the individuals who died was a client of hers. So she might be able to help shed some light on the challenges soldiers face when they come home from war.”

Heloise pulled a sheet of paper out of her bag—a graph of military suicides since 2001—and pushed it across the mahogany table to Aagaard.

“When they deploy, the vast majority are really young men, who don’t have the slightest idea what awaits them when they get there. And now there’s been a fourth.”

“A fourth what?” Mogens asked.

“Suicide. As recently as yesterday, they found the body of a young female soldier, who—”

Karen Aagaard stood up.

Heloise looked at her in surprise. Mogens’s mouth opened in silent amazement.

“I have to run,” Aagaard said and started packing up her papers. “I totally forgot that I have a . . . We’ll have to talk about this another time, right?” She took a couple of steps backward, turned around to face the door, and left the room.

“What the hell?” Mogens said to no one in particular. Then he looked over at Heloise. “She’s acting really weird today.”

Heloise shrugged, still surprised.

“Mikkelsen said this morning that she was out sick, but then she showed up after all . . . I hope nothing serious is wrong with her.”

“With Karen? No way! She’s so ridiculously healthy that it makes you want to slap her. The woman has no vices at all, it’s infuriating. She’s probably just—” Mogens’s eyebrows shot up as he put two and two together. “Huh, it’s probably because of the business with Peter.”

“Her son?” Heloise asked. “What’s going on with him?”

“He’s going to be deployed again. I was with Karen yesterday when he called and told her. She went pretty pale then, now that I think about it . . .”

“I didn’t think he was still in the military,” Heloise said, her brow furrowed.

Aagaard’s son had been in the military for years, but for the last year he had been working as a shift manager for a credit and loan company, and Aagaard had been happy that his days of waging war were over.

“He resigned from BRF, because he wanted to ship out again,” Mogens said.

“And here I am talking about soldiers committing suicide.” Heloise sighed and ran a hand through her hair. “Poor Karen.”

She glanced down at her phone, which was vibrating in her hand. Gerda’s number lit up the display.

“Ah, there you are,” she said into the phone. “I’ve tried calling you a few times, but maybe you’ve—”

“The school is crawling with police!” Gerda blurted out. Her voice sounded unusually loud, as if she were trying to talk over music.

Heloise felt a wave of cold sweat wash over her body. In a hundredth of a second images of various worst-case scenarios flashed through her mind.

A terrorist attack, a school shooting, a teacher unzipping his pants . . .

“Is Lulu okay?” Heloise asked. She was already on her feet.

“Yes. I’m sorry, I should have led with that. She’s with me,” Gerda said. “But one of the boys from the school is missing. I saw him being dropped off this morning and now he’s gone. No one has any idea where he’s been all day. I think he’s been abducted!”

C H A P T E R

7

“WHO HAVE YOU talked to?” Schäfer asked, looking at Lisa Augustin when they were back in the schoolyard.

“Jens and Anne Sofie Bjerre,” she said, pointing to the parents.

They were arguing with a couple of uniformed officers and a woman who looked like a comic strip line drawing, so paper thin that she seemed two-dimensional.