9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

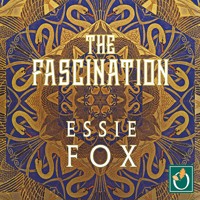

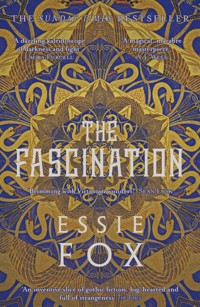

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The estranged grandson of a wealthy collector of human curiosities becomes fascinated with teenaged twin sisters, leading them into a web of dark obsessions. A dazzlingly dark gothic novel from the bestselling author of The Somnambulist. `Makes skilful use of the tropes of Victorian gothic fiction… a story of society's outsiders seeking acceptance and redemption´ Sunday Times `An inventive slice of gothic fiction, big-hearted and full of strangeness´ The Times `A dazzling kaleidoscope of darkness and light´ Laura Purcell `A magical, macabre masterpiece´ A.J. West `Brimming with Victorian wonders!´ Sean Lusk ________________________________ Victorian England. A world of rural fairgrounds and glamorous London theatres. A world of dark secrets and deadly obsessions… Twin sisters Keziah and Tilly Lovell are identical in every way, except that Tilly hasn't grown a single inch since she was five. Coerced into promoting their father's quack elixir as they tour the country fairgrounds, at the age of fifteen the girls are sold to a mysterious Italian known as 'Captain'. Theo is an orphan, raised by his grandfather, Lord Seabrook, a man who has a dark interest in anatomical freaks and other curiosities … particularly the human kind. Resenting his grandson for his mother's death in childbirth, when Seabrook remarries and a new heir is produced, Theo is forced to leave home without a penny to his name. Theo finds employment in Dr Summerwell's Museum of Anatomy in London, and here he meets Captain and his theatrical 'family' of performers, freaks and outcasts. But it is Theo's fascination with Tilly and Keziah that will lead all of them into a web of deceits, exposing the darkest secrets and threatening everything they know… Exploring universal themes of love and loss, the power of redemption and what it means to be unique, The Fascination is an evocative, glittering and bewitching gothic novel that brings alive Victorian London – and darkness and deception that lies beneath… ________________________________ `Fascinating and immersive´ Anna Mazzola `It had me spellbound´ Louisa Treger `A wonderful, captivating carnival of a novel´ Elizabeth Fremantle `Essie Fox's best novel to date – weaves terrors with triumphs, heartache with hope´ Culturefly `A scintillating cabinet of curiosities´ Foreword Reviews `A cast of characters Dickens would be proud of´ Frances Quinn `Rich, dark and heady … a glorious gothic carnival´ Kate Griffin `Magnificent ... a triumph´ Dinah Jefferies `A tender, beautifully written meditation on what it meant in Victorian times to be an outsider´ Historical Novel Society `Darkly gothic, but surprisingly tender ... rendered with such magical and often terrifying authenticity. A marvel´ Damian Dibben `Filled with gothic darkness and glorious hope´ Liz Fenwick `Full of horrors and delights´ Bridget Walsh 'An opium trance of a novel, a vivid fantasmagoria´ Noel O'Reilly `Deliciously dark, full of twists and surprises´ Liz Hyder `What a triumph!´ Emma Curtis `Very fine historical fiction´ Emma Carroll `Truly unexpected and original´ Kate Forsyth `A dizzying potion of a novel´ Polly Crosby `A sumptuous, gothic treat´ Caroline Green `Exceptional storytelling´ Nydia Hetherington `I loved this group of wonderful "others"´ Marika Cobbold `An exquisite novel´ Erika Mailman `Haunting and emotive´ Gill Paul

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 518

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Victorian England. A world of rural fairgrounds and glamorous London theatres. A world of dark secrets and deadly obsessions…

Twin sisters Keziah and Tilly Lovell are identical in every way, except that Tilly hasn’t grown a single inch since she was five. Coerced into promoting their father’s quack elixir as they tour the country fairgrounds, at the age of fifteen the girls are sold to a mysterious Italian known as ‘Captain’.

Theo is an orphan, raised by his grandfather, Lord Seabrook, a man who has a dark interest in anatomical freaks and other curiosities … particularly the human kind. Resenting his grandson for his mother’s death in childbirth, when Seabrook remarries and a new heir is produced, Theo is forced to leave home without a penny to his name.

Unable to train to be a doctor as he’d hoped, Theo finds employment in Dr Summerwell’s Museum of Anatomy in London, and here he meets Captain and his theatrical ‘family’ of performers, freaks and outcasts.

But it is Theo’s fascination with Tilly and Keziah that will lead all of them into a web of dark deceits, exposing the darkest secrets and threatening everything they know…

THE FASCINATION

ESSIE FOX

To Millie Anna Prelogar

You are an inspiration

‘Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster … if you gaze long enough into the abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.’

—Friedrich Nietzsche

CONTENTS

PART ONE

Suffer the Little Children

ONE

An Introduction to

THE MONSTERS

Grandfather snatches at his arm and drags him through the study door. The boy has never been inside, because the room is always locked, though he has often stood on tiptoe with one eye pressed to the keyhole – only to see a soup of shadows. But there are smells, and smells seep out. The ones that puddle round this door are wood and leather and vanilla from the pipe Grandfather smokes. Is that what stains his teeth so brown, even the tips of his moustache and the tufts of bristled white that are sprouting from his ears?

His grandfather looks like an owl, and his nest is very dark, although some buttered rods of light are creeping in around the shutters closed across the big bay windows. They form a ladder on the floor leading towards the painted globe set on a stand beside the hearth. How the boy would like to spin it, to look at all the greens and blues, the lands and oceans of the world. But to do so he would need to navigate the tiger skin lying on the boards before it. The tiger’s head is still attached. The tiger’s eyes reflect the flames blazing red in the grate. They seem alive, and dangerous.

Less threatening are the deer heads mounted high upon the walls. Their softer, melancholy gaze falls across the rows of tables laid with trays containing beetles, butterflies – or are they moths? – of almost every size and colour he could possibly imagine. Inside glass domes are birds and fish, and other animals the like of which he’s never seen before. At least not when he’s been exploring in the gardens or the fields that spread for miles around the house.

These specimens – the old man calls them, letting go of the boy’s arm as he gruffly points them out – are macabre, but beautiful. Some are embossed with silver pins that fix them down on squares of velvet. Some hang on wires, invisible between the palest pinks of corals, pearly shells, or stems of leaves, all being artfully arranged to form the backdrops of displays that represent the distant places where these creatures had once lived. Lived, before they died.

Did his grandfather go travelling to find and then to kill them, to bring them back to Dorney Hall? Sadly, it is too easy to imagine such a thing. And while continuing to stare the child is all but overwhelmed by a sense of loss and sorrow. This, he often thinks when he is older, looking back, is the moment when he first becomes aware that in some vague and unknown future everything that ever lived is doomed to die; although the notion slips away with a blast of onion breath, when his grandfather demands, ‘What sort of age are you these days? I’ll be damned if I can tell. Such a stumpy little imp. But I believe you must have had another birthday recently.’

‘Yes, my birthday was last week, and now I’m seven years of age,’ the boy replies, feeling confused, because birthdays are not events Grandfather likes to celebrate. But Cook, and all the maids, and his governess, Miss Miller, they gathered round the kitchen table. They had him standing on a chair while everyone sang Happy Birthday … Happy Birthday, dearest Theo! How they’d cheered and clapped and laughed, and said that he must make a wish as he was blowing out the candles on his favourite kind of cake. The sort with strawberries and cream.

‘Seven? Is that so?’ Grandfather sounds surprised. His heavy brow is concertinaed into furrows of concern. There is a pause. A mucus crackle in his throat, and then a cough, ‘Well, that’s a rather special number. I must set affairs in motion. You should be off to school by now or you’ll end up a pampered fool, being fussed and molly-coddled by the women in this house.’

Why is the number seven special? Theo thinks about the stories from the Bible he has heard on Sunday mornings when Miss Miller takes him to the village church, and being eager to impress this man he barely ever sees – to prove that he is not a fool – his voice is piping in excitement: ‘God made the world in seven days. Adam and Eve. The sun and stars. When it rained, there was an ark. A great big ship made out of wood. A man called Noah built it, and then he filled it up with every kind of animal on earth. They came in marching, two by two.’

‘The past crushed up as sugared pills and swallowed down by simpletons!’ Another weary sigh precedes the damning interruption. ‘You must think deeper. Dig for truths. What if there were other species? What if the beasts we now imagine as being nothing more than myth may once have actually existed? May still exist today, in far-off corners of the world.’

‘Do you mean the dragons? The …’ What is the word? The boy forgets and, glancing back towards the globe, he recollects a recent lesson when Miss Miller told a story all about some giant bones being discovered by a girl not much older than himself. She’d been walking on some cliffs in quite another part of England. The place, it had a funny name. Something like limes? Or … was it lemons?

‘Dinosaurs,’ Grandfather says. ‘There are displays in London. The British Museum. Perhaps one day you’ll get to see them. But, for now, I’d say it’s time for you to view my own collection.’

‘Your collection?’ Dinosaurs? This is a thrill beyond all measure. How can it be? Where could they be? But then this house is very big. So many places you could hide things. In the cellars, or the stables, or the barns, or mausoleum underneath the private chapel.

‘No,’ Grandfather snaps, before his lips curl in a smile through which his yellowed teeth protrude, ‘But, as it happens, I do have some unusual exhibits.’

Another door is opened. A door you’d never guess was there, made to look like shelves of books. A fusty smell is seeping out. And something sharp and sour too. Is it vinegar, or bleach? The things Cook uses when she’s on a cleaning spree down in the kitchens?

His grandfather is swallowed in a curdling of gloom, although his voice remains quite clear. ‘I’ll light the gas. There are no windows. The darkness helps to stabilise the preservation fluids, whereas the objects that are stuffed…’ There is a grunt of disapproval. ‘Must get my butler to come in and lay more poison down. The wretched vermin in this house!’

Grandfather’s mutterings have stopped, and now the boy can hear the rasping of a lucifer on tinder. There is a swimming green and gold, and the hissing sound of gas as flames illuminate the darkness. It is the eeriest illusion, almost like being underwater. Suddenly, he cannot breathe and even fears he might be drowning. Can he turn and run away, back through the hall, and up the stairs?

But the doorway to the hall is entirely lost from view when, for the second time that day, Grandfather reaches for his arm and almost lifts him off his feet, ‘For pity’s sake! Stop whimpering. There’s nothing here to be afraid of. At least’ – a phlegmy chuckle precedes the cryptic inference – ‘not in their present forms.’

Like Alice falling through the glass, the boy’s whole world turns upside down. Now he is on the other side of what appears to be a cupboard, little bigger than the store in which Cook keeps her jams and pickles. His head is spinning. He feels sick as he inhales metallic fumes. His eyes are drawn towards the dirty-looking leather of a glove left on a stand beside the entrance. But, oh, the horror of the thing when Grandfather picks it up and says it’s not a glove at all, but a hand that has been severed from a man accused of murder, who met his death upon the gallows, over three hundred years ago.

‘It’s called a Hand of Glory.’ Grandfather holds the ghastly thing underneath a burning jet, and now the boy can clearly see the stringy tendons that protrude through the mummified grey flesh, the horny ridging of the nails. ‘People had them dipped in wax, threaded the fingers through with wicks … lit them up like candelabras!’

The hand is thrust towards him. The boy cries out and stumbles back against the wall with a thud. His shoulder is hurting, but there’s no sympathy to follow. Only the bark, ‘Where is your backbone? Lily-livered little urchin! My wife was just the same. Not that long before she died, she found me here … and what a scene. Ran through the house screaming blue murder.’

The boy would like to scream. The sweat is breaking on his brow. The flutter of his heart could almost be a frightened bird; wings beating hard against the trap of the ribs that curve around it. His breaths are coming much too loud, almost like thunder in his ears when, behind a wall of glass he sees a head without a body. The marbled blue of shocked round eyes could be his own reflected back. But from this other child’s brow protrudes a gnarled and curving horn, like the tusk of the rhinoceros he’d looked at yesterday in Miss Miller’s illustrated Animals of Africa.

He turns away with a shudder, only to see a larger head. This face is covered in dark hair. The sawdust spilling through one nostril looks like a lump of crusted snot. Two dark-brown eyes stare blankly out through a pair of swollen lids. A snout has lips curling back to show the sharpness of the teeth poised in the moment of a snarl. Underneath, fixed to the plinth on which this horror has been mounted is a tarnished metal plate. Silently he mouths the syllables engraved in the brass: ‘Ly…can…thrope.’

What does it mean?

Feet shuffle on. His nose is pressed against another wall of glass, mouth dropping open as he wonders, Can this bea real mermaid? He thinks it is a she, but ugly like a chimpanzee. A face as wrinkled as a prune below a scalp entirely bald. The tail extending from the waist is the dull brown of flaking rust. Several scales have fallen off and are scattered like confetti across the base of the container. What’s left is blighted by black mould, like rotting carrots left forgotten in the bottom of Cook’s basket.

A narrow ray of sunlight shafts through the door and draws his eye towards a jar that, till that moment, had been concealed in veils of shadow. The skin of what it holds is white and luminous, like pearls, while underneath there is a pale-purple tracery of veins. The tiny hands are splayed like starfish. The shell-like ears are pixie-pointed. A rosebud mouth appears to smile, as do a pair of milky eyes that are occasionally hidden by some wisps of fine fair hair that slowly waver as they float in a cloudy amber liquid.

He feels the queerest of sensations, as sweet as honey in his belly when he notices the place where the shoulder blades should be, and where…

Is that a pair of wings? But, if they’re wings, is this is a fairy? A real-life fairy, in a bottle?

The fascination has begun.

TWO

Some freaks are born, and some are made. But when it came to Tilly Lovell, it was no natural quirk of fate the way that I kept sprouting up to reach a normal adult height, whereas she stopped at three foot six. Who would believe that we were twins, and identical at that? As like as peas in the one pod on the day that we were born, when – according to our pa, Alfred Nehemiah Lovell – he could cup his mewling daughters in the palms of both his hands. One on the left. One on the right. Like a pair of kitchen scales.

A miracle that we survived. The child that followed us did not. We should have had a baby brother, but Pa said he wasn’t right. Unlike ourselves, he’d been too big. Ma wasn’t strong, and as she’d lain there on the bed and breathed her last, our ill-fated little sibling also gave a feeble gasp. He left this world held in her arms. They lie together in one coffin.

Such a tragedy it was, and what a thorn of bitter gall it left in Alfred Lovell’s heart. Not that his heart was ever sweet. To tell the truth he wasn’t fit to play the part of any father – which is exactly what I’d say if the man should have the cheek to show his face to us again. Though I occasionally wonder, would I know him if he did after so many years of absence? Would his hair have turned to grey or still be gleaming, black as coal? Would his whiskers still be tweezed to two waxed tips below a nose swollen and grogged with boozy veins? I have no doubt I’d recognise him by his one remaining eye, always the mirror of our own. Very dark and slightly slanting, loaning a hint of the exotic – which is because we have the blood of the Gyptians in our veins. And that’s a heritage I’m proud of, although I’m somewhat less inclined to boast of an affiliation with the mercenary man who thought so little of his daughters that he gambled them away one summer dawn on Windsor Brocas. For all he knew he could have flung us both into the fires of Hell. Instead of which, my sister Tilly, she went soaring like the brightest of the stars in London’s skies … in which the Fairy Queen Matilda bedazzled all who came to see her.

When did Tilly stop her growing? We were five, or thereabouts. Our ma had died, and Alfred Lovell was too rarely in the house to offer comfort when we cried ourselves to sleep most every night. Our attic room had beams so low we only had to raise our arms to touch the cobwebs spun between them, where the moonlight often shafted through the latticed window glass. Beyond those drifts of silvered gauze, me and Tilly would pretend that we could see the spirit features of our mother smiling down. Her dark-brown eyes were filled with sparkle. Her cold white fingers stroked our hair as it lay loose across the pillow she’d once slept upon herself. For many months after she’d gone we could still smell her body’s fragrance seeping through its cotton cover. Rose and amber and patchouli. But little else of her was left. What Pa had done with all her clothes, her silky scarfs and coloured beads, we didn’t know. Not at the time. But we had watched him strip the linen from their bed, then lug the mattress to the bottom of the garden. The lot was doused in paraffin and set ablaze in a great pyre.

It was still smouldering next morning when me and Tilly poked some twigs around the glowing ruby embers. All we could see were gritty ashes stirred by a sudden draught of wind to rise and float towards the cottage, almost as if our mother’s soul was creeping back through all the cracks around the rotting window frames. Or was she hiding in the thatching, among the nests of birds and vermin, from where her fingernails would scratch and tap above us in the night? And what about the layers of grime that, in her absence, settled thick on every surface in the house? It was a wonder that our pa had not been buried in that shroud, for if he wasn’t in the pub, he’d be slumped across a chair, his open mouth drooling black spittle from the baccy he’d been chewing.

As he festered grim and silent, we went unwashed, wore filthy clothes and lived on crusts of mouldy bread, or else the rancid nibs of cheese that, before, our ma would use to bait the traps for any vermin. Meanwhile, we fretted over how to tell our father of our plight, for with the man so rarely sober we were more likely to receive a spiteful lashing from his tongue than any words of consolation.

Still, desperation made us brave, particularly Tilly. Always the twin to take the lead, there came the night when she advanced across the parlour’s creaking boards so as to tug upon Pa’s sleeve. When that garnered no response more than a heavy grunting snort, her fingers stroked across his brow and traced the netting of the scars that puckered close to his blind eye. Meanwhile she turned to me and whispered, ‘Keziah, Pa feels hot. You don’t suppose he might be…’

Sick? About to die? Is what we thought, for if our ma could pass so unexpectedly, then why not Pa as well?

‘Give his hair a good old pull. Do it hard, and like you mean it,’ was my suggestion at the time, which Tilly did, while calling out, ‘Pa, please … you must wake up! We can’t find anything to eat.’

As quick as lightning he revived from his intoxicated trance, but with a terrible result. Barely before his good eye opened, one of his hands grabbed for the poker that was lying in the hearth. As he lashed out, the iron tip whacked against poor Tilly’s temple. She stumbled back and hit her head upon the floor with such a crack I feared her skull had split in two.

All Hell broke out in that one moment. Between my screaming, Pa rose up, jabbing his weapon left and right as if he thought he was a knight intent on slaughtering a dragon. A dragon no one else could see. Quite petrified, I wasn’t sure if I should find somewhere to hide, or face his wrath and rescue Tilly. But, in the end there was no need. It was as if the mist of rage melted from his cyclops eye. Now, standing still, but for the swaying back and forwards on his feet, his voice was slurred and thick with guilt. ‘I thought your sister an intruder. Mayhap the bailiffs, come to take whatever valuables are left. There’s rent still owing on this house for which the farmer grows impatient. And then the funeral expenses. That bastard of an undertaker! I should ’ave burned your mother’s body with the bed, or carried it up to the woods, to dig a hole…’

I pressed my hands against my ears to try and stop the awful words. I couldn’t bear to think of Ma shut up inside her wooden box in the graveyard of the church. And what if Tilly went there too?

For then, my sister’s eyes were open, staring blankly up at mine, before they rolled back in her head. With just the whites of them remaining it was the most alarming sight, as was the way her sightless body twitched and shuffled on the boards.

‘Pa, you have to do something!’ I all but screamed in my distress.

He merely muttered with resentment, ‘Suppose this means more money spending. We must hope it’s just the doctor. Not another bloody coffin.’

His hands delved into trouser pockets. There was a satisfying chink, but when he drew the money out, he only scowled and shook his head before he stormed from the house, slamming the door so hard behind him that any objects not nailed down and hammered into place rattled and thrummed like tambourines.

With my own nerves in tattered shreds, I climbed the stairs to fetch Ma’s pillow, coming back to gently rest my sister’s head upon its feathers. After that, I settled down on the floor at Tilly’s side and spooned my body into hers – which was what I always did when we were sleeping in our bed. Above the flutter of her breaths, I heard the twitter of the birds in the trees outside the window. I saw the shadows of the leaves dancing like fairies on the plaster of the walls between the beams as daylight dimmed and turned to dusk. When there was nothing but the gleaming of the moon on Tilly’s face to show a spreading purple bruise, she suddenly let out a moan, and then complained of being thirsty.

Off I went to fill a cup with water from the garden pump, which Tilly drank in one long gulp before she drifted back to sleep. Much relieved and oh-so grateful to think my sister would recover, I also dozed, but fitfully, until the dawn when she awoke a second time and grabbed my hand…

‘Keziah,’ Tilly said, ‘my head is aching something awful, and the room is spinning round. I think I’m going to be sick.’

What to do? I didn’t know. Could I soothe her with a story? Perhaps the one our ma had read to us so often we were able to recite the words by heart – just as we’d done beside her grave after the funeral was done, when our pa and his clan of bosky drinkers disappeared to continue with their mourning at the local village tavern.

As we’d settled on the grass, legs dangling down into the void in which Ma’s coffin had been laid, we’d found more comfort in the words from her old book of fairy tales than anything the vicar read from his Bible in the church. To us, Ma’s book was just as sacred, with its covers of green leather worn as soft and smooth as velvet, in which the pages were so thin they seemed no more than wisps of air. But they contained such wondrous tales that lived and bloomed inside our heads, such as Snow-White and Rose-Red, which our ma had always said was like a mirror of our lives –

THERE WAS ONCE A POOR WOMAN who lived in a lonely cottage. She had two children who were twins. One was called Snow-White, and the other was Rose-Red, named for the rose trees grown in pots beside their cottage door.

The girls were always happy, and loved each other dearly, so much so that if Snow-White should chance to say: ‘How I hope we are never forced to part,’ Rose-Red would reply: ‘Never so long as we’re both living.’

In summertime, the girls would often gather berries in the forest, where the deer would stand and watch them and the birds would perch on branches of the trees and sweetly sing. Even if they lost their way or lingered late into the night, they would simply rest their heads on mounds of moss and then awake to carry home the wild flowers to place upon their mother’s pillow.

During the winter months, the sisters stayed at home keeping warm beside the fire. One cold, dark night when it was snowing, and so thickly that the forest was a wonderland of white, they heard the sound of distant howling, after which their mother shivered and then said, ‘Snow-White, get up. Go and bolt the cottage door. We must be sure to keep it locked against the hungry wild creatures that might try to come and eat us.’

Another evening they were sitting by the fire when they heard the loudest knocking at the door. This time, their mother said, ‘Quick! Rose-Red, undo the bolts, for it may be a traveller lost in the woods and seeking shelter.’

Rose-Red did as she was told, but instead of any man or woman standing in the porch she saw a big black bear, which pushed its head in through the door, and…

How strange to think that while my sister and myself had been immersed in the reciting of that tale we’d never dreamed that, in due course, a bear would enter our own lives.

Ah! Your ears are pricking up. But on that day the only sound to prick our ears had been the singing of the birds among the trees as we got up to pick some flowers to decorate Ma’s coffin lid – just as the sisters in the tale placed flowers on their mother’s pillow. The sole adornment from our father had been the handful of dry soil scattered down into the grave during the saying of the prayers. Now, me and Tilly found some daisies growing by the churchyard gates. Yellow chrysanthemums as well from a fancy iron urn. And, yes, we knew it was a sin to steal from another grave, but there was no one there to see us…

If a sin has not been witnessed, does it count as being real? Would our ma have been ashamed and disappointed in her daughters? If only she’d been there to ask, and again a few weeks later when my sister lay there senseless on the floor with rays of dawn gilding her bruised and swollen face. The morning light, it also flickered on the darkness of the mole that could be seen on her left cheek. The only difference between us, it looked exactly like a heart, and how I’d hankered for the same. However, Tilly didn’t like it, one day picking till it bled, after which it was to form a sore and crusty-looking scab.

That would have been about the time when Ma was swelling with our brother, and come one warm spring afternoon when she’d gone upstairs to rest, Pa said he’d take us on a stroll to offer her an hour of peace.

In an uncommon cheery mood, he led us on a detour through the trees that formed a dingle at the outskirts of the village, on the other side of which was the home of Betsy Jones. We didn’t like that gloomy cottage where every window we could see was laden up with old clay pots. So many plants with funny smells, while above them were the corpses of frogs, or mice and moles strung up on metal wires, looking like strips of shrivelled leather.

Betsy herself looked somewhat feral, with brindle hair and amber eyes. She was what people in those parts would label as a cunning woman, somewhat in the witchy mould; what with the writing of her charms to help to heal a person’s woes, which she would often do for free. But, for the potions brewed from herbs, or else ingredients you wouldn’t want to think about at all, then Betsy always wanted money, and if the coin was not supplied her medicines would never work. Well, that’s what Betsy said.

On that day, our pa gave Betsy Jones a shining silver sixpence, the reason being – so he said – that our ma had grown concerned about the state of Tilly’s mole, and if Betsy had a charm that could spirit it away, or simply stop the girl from picking, he would be immensely grateful.

Was it true that Ma had sent him? It may have been. I don’t remember. But there we stood in Betsy’s house, watching mutely as she led our pa behind the old sack curtain that led on into her kitchen; supposedly to go and make themselves a brew of tea – though who would guess that such a task could prove to be so arduous? What heavy sighs and gasping groans were punctuated by a deal of rhythmic knocking and loud crashes. We had to wonder, were they throwing all the china from the shelves?

Eventually, the noise subsided and we could hear Pa telling Betsy, in a breathless sort of voice, ‘I fear the child may have been cursed … that the devil’s left his fingerprint to mark her as his own. Isn’t that what people say?’

As our hearts began to pound, Tilly’s hand reached out for mine, and Betsy Jones let out the most disturbing cackle of a laugh. ‘Alfred Lovell, I would say your head’s more addled than I thought. That is nought but superstition. But if you wish…’

More mumbled words, too subdued for us to hear, and then the curtain was flung back and there was Pa, and there was Betsy, and pincered in the woman’s fingers was a common garden snail.

‘Come over here now, Tilly dear.’ Betsy beckoned with a smile as she swayed across the parlour and settled on a chair drawn up close beside her fire. Smoke was rising. Flames were dancing. Logs of wood were crackling with small explosions of red embers – almost as if to warn my sister not to venture any nearer. But, to my open-mouthed amazement, Tilly obliged and bravely walked straight into Betsy’s ham-hock arms, where she was lifted from the ground as if she weighed no more than air. My sister didn’t even gasp when Betsy Jones then proceeded to hold the snail against her cheek. But, oh, to see that sluggy body extending from its shell to leave a trail of silver glue across the scab of Tilly’s mole! Truly, I thought that I should faint.

At least the job was swiftly done. Betsy set Tilly down again, and then told Pa, ‘I’ll put the snail in a box. You take it home. Make sure to bury it in soil directly underneath the window of the room where Tilly sleeps. As the creature dies and shrivels in its shell, so Tilly’s mark will also fade and disappear.’

Well, if that wasn’t superstition, I don’t know what Betsy called it – and it didn’t even work. By the summer following, when Tilly lay there near to senseless on our own hard parlour floor, the mole was very far from shrivelled. If anything, I thought it larger, tracing a finger round its contours, before I stood and made my way towards the window to the lane.

Peering morosely through the curtains, between the overgrowth of roses and the ivy that was clambering across our cottage front, I strained to see a little further through the tunnelled green of trees where morning birds were symphonising. A breeze was playing through the leaves, and as they fluttered up and soughed, I heard the whisper in my mind: Where are you, Pa? Why have you left us?

Not expecting any answer, I took myself into the kitchen, where I stared in bleak dismay at the copper that once heated the water for our baths. How long could it have been since Ma last soaped our dirty hair, while me and Tilly sat and giggled in the scummy froths of bubbles? Although in truth, the final time, Ma had been so big with child she couldn’t bend and had to leave us to our own splashing devices. But she’d still smiled; that lovely smile, in which she had a certain way of almost pursing up her mouth, as if inviting you to kiss it. Who wouldn’t want to kiss those lips, or stroke a finger through the lustrous hair that shone as dark as jet? Who wouldn’t want to gaze at eyes always so bright and luminous, with a magnetic sort of glamour? Why, even Pa, on one occasion, in a fit of reminiscing, told us those eyes had been the thing about our ma that won his heart, that just one flutter of her lashes and his darling could have lured all of the birds down from the trees.

That last day we’d spent with Ma, when we’d been soaking in the tub, her eyes were puffed and red, ringed with the shadows of exhaustion. Her hair was limp and thick with grease, much of it falling from the scarf she’d used to hold it from her face. When she sank down into her chair her feet were raised upon another, hoping that way to ease the swelling of the flesh around her ankles. Her hands were just as bad, blown up as fat as sausages. The night before, Pa was so worried he’d gone off to visit Betsy, only returning hours later, looking flushed about the face and holding phials containing tinctures made from dandelion flowers mixed with the boiled leaves of nettles – for all the good that potion did.

Ma’s wedding ring became so tight the skin around it turned to black. She’d had to rub it with the soap from our bath to grease it free, and then she’d dropped the flimsy band onto the table at her side. After that she’d closed her eyes and touched a chain around her neck, on which another ring was looped. In the glisten of the candle that was burning on the table I saw the glint of coloured stones and excitedly enquired, ‘Where did you get such treasure, Ma?’

‘Long ago, this belonged to my great-great-grandmother. She was a legend in our tribe. Bohemia was her name, and bohemian her nature. Ah, what tales she would recount about the lovers in her life … even the time when she once had two husbands living in her vardo.’

‘Both of them at once?’

Ma didn’t seem to hear my question, her tale already moving on, ‘Then she took up with the admirer who’d gifted her this ring … whose veins ran blue with royal blood.’

‘Who was it, Ma? The king of England?’ Now Tilly’s interest had been piqued.

‘Bohemia would never say. But I don’t doubt she told the truth. She’d been a beauty in her time, but she was also sharp as nails, knowing her letters and her numbers, which in turn she taught to me. Now I have passed them on to you. My clever girls!’ Ma smiled indulgently before she carried on…

‘Bohemia had a gift for the prophesying arts. She used her deck of tarot cards, and a crystal ball for scrying. So accurate were her readings, rumours spread to say she must have had some dealings with the devil. Perhaps there was a darker side.’ Here, Ma sighed and left a pause as if considering her thoughts. ‘I never did approve of curses, but I know to my own cost that Bohemia possessed a power mightier than most. When I was but a girl of ten and she much nearer to a hundred, she predicted my own future.’

‘Did she read…’ I started off, while Tilly finished with, ‘…your palm?’

We were like chicks inside a nest, cheeping as one, mouths opened wide as Ma continued to explain, ‘We used her cards. I cut the deck and laid them out, and…’ Ma’s dark eyes went oddly vacant, making me fear that her mind had wandered back into the past and left her body in the kitchen. ‘What resulted from that reading was the warning that the man I chose to wed would first betray me, then lead me to an early grave, in which…’ She placed a hand on the great doming of her belly ‘…I would not lie alone.’

‘Did Bohemia mean Pa? Did she mean Pa would try and hurt you?’ My voice was breathless with the dread.

‘Well, I have had no other husband, and from the moment we first met, I must confess that I was lost, quite bedazzled by his charm.’

Here, Ma began to sing:

‘A blacksmith courted me nine months, and he fairly won my heart.

His cheeks were red as roses, his hat was decked with marigolds.

He looked so handsome and so clever with his hammer in his hand,

I thought, if he could be my love, I…’

Ma broke off for a good while before she spoke to us again. ‘I didn’t know. How could I know?’

Know what? What could we say to fill the silence she’d left hanging? But, on the other hand, though we were not much more than babes, Tilly and me had seen enough to understand that there were often ugly demons that possessed our father’s body, and his mind. Mostly those times when he’d been drinking.

It wasn’t something good to think of. The air felt ominous and heavy. Such a relief when Ma’s dour frown melted back into a smile. ‘I’m glad I didn’t listen to the warnings I was given, for if I’d never wed your pa I wouldn’t have my darling girls, and you do bring my heart such joy. Will you both remember that, even when I am no longer sitting here to tell you so? And in time, when you are older, promise me you’ll get away … as far from Pa as possible.’

She raised the chain that held Bohemia’s old ring above her head, setting it down upon the table where its glamour put to shame the battered wedding band from Pa. She slowly stroked the coloured stones, and said, ‘When it’s time for you to go, then with my blessings you may sell this. Share the value equally. But, for now, I’ll keep it hidden. Just in case…’

She must have meant in case of Pa rooting through her valuables, taking away the better objects to pawn, or else barter, though what he did with any money, it was a mystery. And when it came to buying food…

Oh, how I hungered that morning, when my sister still lay senseless in the room across the hall – when I stood there in the kitchen and dreamed of mornings when we’d wake to hear the kettle’s breakfast whistle, leaving our attic bed to make our yawning way downstairs, seeing the table newly scrubbed and laid with plates of still-warm bread smeared with butter, sweet red jams, or golden honey from the jars now empty on the dresser shelves.

While I was staring at those jars, I heard the distant, hollow chiming of the church bell in the village. Holding my breath, I concentrated as I counted: One, two, three, four, five, six, seven…

Could it really be that hour and still no sign of Pa come home? Where had he gone, to be so long? The doctor’s house was not that far. Had he been set upon by thieves, or maybe stumbled on the way and hit his head, the same as Tilly?

With my own noggin filled with panic, the awful gnawing in my belly drew my eye towards a tin that still contained stale biscuit crumbs. Spitting on a finger, I rubbed the tip around inside, and as I licked the grains of sweetness I scanned the dresser shelves once more – to see a jar containing oats, though much too high for me to reach. But, if I dragged a chair up close and stood on that, then stretched my arms…

I heard the slow but steady thud of footsteps coming up the lane, and then the whining of the gate, before the rattle of the latch. Somebody at the cottage door?

‘Pa?’ I called his name, heard no reply, so called again, but in a voice far less assured, because my mind was all a spiral: A stranger in the house? One of those men our pa had mentioned coming here for money owing?

A desperate trembling overwhelmed me, and my balance, which had been precarious to say the least, was now entirely lost. At the same time my fingers brushed against a decorated vase that held dried stems of lavender. Flying to the floor, I only suffered a sharp jolt to my arse and my left elbow. But the vase, it fared much worse. My legs were splayed among what looked to be a hundred shards of china, and scattered through the debris were the beads of purple flowers that had fallen from their stems. There were other things as well. Pennies, tuppences and crowns, and – could that be a sovereign? I also saw the plain gold ring that had been pinching at Ma’s finger. And then the one with coloured stones, both of them spinning rapidly on a trajectory that led them straight towards the pair of dusty boots planted in the kitchen doorway.

Raising my eyes, I couldn’t help but see how rumpled Pa was looking, even worse than usual. Mud was smeared across his trousers. Long stems of grass and curls of ivy were tangled through his hair. Had he been sleeping in a ditch?

While thinking this, I struggled up and stood among the broken china. Rubbing a hand at my sore elbow, I asked, ‘Pa, where is the doctor?’

His reply was but a grunt, his good eye focused on the rings that now lay still beside his feet: ‘Where is your sister?’

‘She’s still sleeping. Where you left her.’ I took a step towards him, meaning to try and steer his body round to face the parlour door. But as I pulled, he jerked away, his voice so low I barely heard it. ‘All these coins. Your mother’s rings. Where did you find them, girl?’

‘In the vase. I’m sorry Pa. I didn’t mean to break it. I knocked it off the shelf when I was looking for—’

His laughter drowned me out. ‘Well I’ll be damned. The wily bitch, hiding all of this away from me, when I was shamed to have to beg to save her from a pauper’s grave.’

‘Pa, please…’ How to distract him? ‘I’ll fetch a brush. I’ll clean the mess. But, what are we to do with Tilly?’

‘Don’t nag! Bad as your mother,’ he snapped aggressively. ‘You can pick up all these coins, and no filching while you’re at it, for I shall know, and you’ll be punished!’

Before my task had even started, he’d snatched the rings from the floor and stuffed them deep into the pockets where coins had jangled hours before. Meanwhile, I forced myself to ask about the doctor yet again.

‘Wasn’t home.’ Pa growled his answer. ‘Visiting another patient. But, as it chanced, my luck was in. I stopped by The Angel Inn, and…’

‘Oh Pa!’ As I was setting all the coins upon the table, the disappointment I felt was too apparent in my voice. Had he been drinking through the night? I couldn’t help but think of times when Ma despaired of his behaviour, of how she’d cried when he’d eventually come home to her again. I felt inclined to do the same, but was afraid of his reaction, especially when he drew nearer, hot blasts of breath and sprays of spittle falling on my upturned face: ‘Shut the pester of thy mouth! That doctor’s nothing but a leech, bloated and fat with what he sucks from ailing folk he claims to save. Now, Betsy…’

‘Betsy Jones?’ I couldn’t breathe. In my mind’s eye I saw again the squirming snail, the gluey slime on Tilly’s cheek.

‘The very one.’ Pa took a pause and started counting through the coins, which he then placed in separate piles arranged according to their value. ‘We shared a bevvy, me and Betsy, and she suggested just the thing to help revive your sister’s spirits. I would have brought it back the sooner, but…’ His one eye glinted as a hand dipped in his pocket for a bottle. ‘This ’ere is Betsy’s potion. Only two pennies, and she swears that it will perk our Tilly up. Worth a punt, wouldn’t you say?’

I thought, but didn’t say that Betsy’s snail hadn’t worked, so why should this be any different? I watched him turn towards the hall, feet crunching over broken china as I followed in the wake of booze and sweat the man exuded. And something else I didn’t know. Something yeasty, sweet and musty. It made me feel a little sick, having to swallow back the bile as my eyes were firmly fixed on the bottle in Pa’s hand. It held a liquid, dark and viscous, clinging like glue to the glass sides. Same as the words inside my mouth, too thick to speak, but still the thought: What if it is poison? Did Betsy’s potions kill our ma?

There came a sudden popping as the bottle was uncorked. I saw Pa lift it to his mouth and take a swig of what it held. So, perhaps it wasn’t poison. But it did reek of something fierce, and under that … was it molasses? What Ma laced through her Christmas biscuits? I must admit, like miracles said to occur during that season, the medicine did seem to hold the magic spell to cure Pa’s ills, for he sighed with satisfaction, smacked his lips, then made his way into the room where Tilly lay.

Following behind, I stood and watched and held my breath as he knelt down upon the boards. I saw him lift my sister’s head and pour the potion in her mouth. I heard her gasp, and then a cough before she struggled to sit up and rub her knuckles at her eyes, after which it did appear some vibrant flame was set alight. Something that filled my sister’s blood and stirred her up like rising batter. First, she looked in my direction, then at Pa as she enquired, ‘What happened? Did I sleep here in the parlour all last night? I can’t remember anything, only a hurting in my head. But now I’m better, and I’m hungry. Is there anything to eat?’

Pa laughed and cupped her face between his rough spade hands. He kissed her button nose, and then the spreading purple bruise. What a sweet and tender vision. It left me feeling quite neglected, until I found that I was bathed in his benevolence as well. A thing so rare that when it happened you couldn’t help but feel beguiled. You quite forgot about the moody, moaning monster he had been only a moment earlier. When you saw this other Pa, you understood why Ma had fallen for his handsome, roguish charms. It was as if a golden light was somehow shining through the mud. It made you want to smile. It made you feel as if you’d trust him to the moon and back again – that you’d do anything he said.

So, there I was, his willing slavey when he spoke in a voice as dark and syrupy as what he’d just poured into Tilly’s mouth: ‘My darling girl, Keziah, won’t you take yourself a shilling from the table and then walk across the fields to Kenton’s farm. Ask for butter, eggs and milk. A loaf of bread if they should have it. And leave the change towards what’s owing. When you’re back, we three shall have ourselves a proper slap-up breakfast, before your pa goes off to make another visit with his Betsy … for it do seem,’ he tapped the pocket that now held our mother’s rings, ‘I have the means and the ambition to invest in a new venture. An enterprise that cannot fail.’

THREE

DINNER WITH MISS MILLER

Theo’s top hat, his black-tailed coat and white cravat are on the floor. As the waistcoat also drops, he settles on the bedroom chair. He holds his head cupped in his hands, rests his elbows on his knees, and wonders to himself: Which of my prisons is the worse?

Is it Dorney Hall, where he’s returned to spend the summer, or Eton College, where he boards, which is so near that he could walk all the way there and back again between his breakfast and his lunch? At least he has a private dorm, and although it may be spartan, almost anything is better than the prep school he was sent to at the age of seven years. A real ‘do the boys’, where the luxuries of down and quilted silk were replaced by cold damp mattresses and sheets, with pupils crammed into the beds like sardines inside a can. Theo, who’d known no siblings, who had no friends of his own age, was tortured by the clamour of all the laughing, snoring, farting, or the sobs from other boys who mourned the absence of their mothers.

Theo misses his mother, even though he’s never known her. But this room at Dorney Hall had been her nursery as a child, and though it may be fanciful there are times when he believes he can hear her girlish laughter, as if an echo on the air. He likes to wake in the same bed. He likes to touch the dark oak bedposts carved with winding leaves and flowers, or the drapes of blue damask, the colour of a summer’s sky. The walls beyond, a pale-green silk.

Today with all the casements to the garden being opened, the air is hazed with specks of gold. Sprays of coloured rainbows flash from his waistcoat’s silver buttons and also dazzle on the mirrors set into the wardrobe doors. If he squints into the glass he can still see the little boy who’d loved to ride the rocking horse in the window’s curving bay – who used to hold his arms out wide and make believe that he was flying over the garden and the trees, into the clouds, towards the stars. The stars on which he’d wished to grow to be a man as tall, or taller, than his grandfather, Lord Seabrook.

These days the bully’s stance is somewhat less intimidating. Lord Seabrook’s shoulders slope. His once-thick hair is little more than a straggling grey fringe around a freckled, monkish dome. As for the tusks of his moustache, it is impossible to see him without thinking of a walrus – ‘“O Oysters, come and walk with us!” The Walrus did beseech. A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk…”’

Lord Seabrook has no pleasant talk. And when it comes to walking…

Theo was only five when his grandfather decided that his legs were much too short and not as straight as they should be. One day, a specialist arrived, taking measurements with pincers. A week later, he returned to fix some callipers in place. A leather strap was buckled tightly under each of Theo’s knees, and from these a metal rod – to be adjusted every month – ran down each outer calf; almost like a pair of stirrups fitting underneath his boots. He’d had to wear them every day, no matter how they chaffed and blistered. And they did. They made him limp. They were so heavy he’d been forced to drag his feet when he was walking. Running was impossible. It was his governess, Miss Miller, who’d finally insisted that the boy be left to live as Nature had designed him, and that the tortuous contraptions were never buckled on again.

What sort of warped sadistic mind would think to do that to a child? Theo ponders as he strokes the fuzz of golden stubble newly bristled on his chin. What grows around his sex is now much wirier to touch. Unconsciously, his hand is lowered, beneath his shirt, across the tautness of the muscles of his belly, further down as he drifts into another fantasy about the doe-eyed Persian boy who once came into his dorm to ask advice about some essay, or was it maths? Theo forgets. But he remembers soft brown skin, and parted lips, and …

And from lower in the house the dinner gong is sounding, which stirs another thought even more urgent and demanding: Must get dressed for dinner. Must not be late and risk incurring the wrath of the old man.

When the gig arrived to fetch him home that afternoon, the driver handed him a note in which his grandfather requested Theo join him for dinner. How oddly formal that had seemed. Will Miss Miller be there too? His ageing governess’s sweetness always dilutes the air of tension between Lord Seabrook and himself. Even though he has no need of her tutoring these days, her constant presence in the house provides the comfort and affection most other boys would find in mothers – which is why Theo experienced a pang of disappointment not to see her on the steps when all the other household staff came out to greet him earlier.

Has something happened? Has she left? Surely someone would have said?

With a sense of dark foreboding, hurriedly, a little clumsily, he stands and steps across the clothes discarded earlier. Opening the wardrobe doors, he stretches up and removes his favourite linen jacket. But what had fitted well last summer has already grown too tight. The seams are straining, fit to burst; horizontally at least. The torment of the swimming and the rowing he’s endured these past few years at Eton College have honed and sculpted his physique, though he’s not sure about his mind. Grandfather’s barking inquisitions almost always leave him tongue-tied.

The gong resounds a second time. He thrusts his feet into his boots, still warm and damp from earlier. Hobbling at first, his pace increases by the time he’s reached the old oak staircase. Treads groan and squeak as he descends. Somewhat more mutely he’s observed by the glazed and dusty eyes of all the Seabrook ancestors who stare from frames hung on the walls. And above the final stair there is the portrait of his mother.

Theo lingers as he contemplates the face of Theodora, who died when he was born. Not that he needs to look that hard. It is engrained upon his mind, this romantic Millais vision of a beautiful young woman sitting on the large carved chest still in the drawing room today. As are the yellow drapes that form the background of the portrait. Forever seventeen – the same age that he is now – her arms are bare, as is her neck, at which she wears three strings of pearls. Her dress is blue. A gauzy silk, or is it muslin? Very fine. A small bouquet de corsage has been pinned against her breast. The flowers are forget-me-nots. In her white hands she holds a fan, while at her side is the cream leather of a glove she has discarded.

Theo can never see that glove without remembering the horror of Grandfather’s hand of glory. Better to concentrate instead on what is on her other side. A Chinese pot containing stems of purple hyacinth, narcissi…

Can he smell their perfume now? He looks away, his clear-blue gaze (so like his mother’s in the frame) is moving on across the gleam of the hallway’s polished boards. Over these his footsteps echo as he turns into a passage, at last arriving at the door where he will pause and take a breath, hoping to summon up the courage he will need to step inside.

When he does the room is empty. The table is not laid. No silver dishes on the console, on either side of which the doors to the terrace have been opened. A sudden breeze catches the drapes, and there’s the perfume he noticed at the bottom of the stairs, from the wisteria and lilac growing across an arched pergola, while sitting underneath it is…

‘Miss Miller! You’re still here.’ Theo is so pleased he wants to clap and shout ‘hurray’.

Meanwhile, the glass that she is holding to her lips is swiftly lowered as she cranes her neck around, and her sweetly lilting voice is replying in delight, ‘Ah, there you are. My dearest boy. And look, how handsome you’ve become in just the past few months. Quite the young Adonis, and…’ she beams ‘…have you grown?’

Seeing his frown, the shrug of shoulders, she knows it’s best to change the subject. She motions to a jug, ‘Some ginger ale? I know you like it. Or perhaps a glass of wine? The claret served with lunch today was very good. Perhaps too good.’

Miss Miller’s hand touches her head, where several wisps of greying hair are falling loose from their pins. ‘I had a nap this afternoon, which is unusual for me. I feared I might have been unwell. Felt very feverish and tired. But then, this weather is so warm and … Oh!’ Miss Miller is distracted as she glances out across the verdant slope of garden lawns. ‘Whoever can that be?’

Her silver lorgnette spectacles are lifted from the table and pressed against her nose before she lowers them again. ‘I thought I saw a man standing by the birches at the farthest boundary walls. Would the gardeners still be working? Or…’ now her turn to frown ‘…is it a breeze in the branches? They sometimes throw the strangest shadows.’

‘Is it Grandfather?’ Theo asks. ‘Gone for a walk before the meal?’

Her powdered cheeks are flushing pink. Sweat is beading on her brow. ‘No, he left this afternoon. Gone to the Knightsbridge house. A telegram arrived. Some business needing his attention. I’ve really no idea. But it must have been important. He started shouting for his man to pack his bags without delay, which I did think was rather odd, because I know he’d been planning on a dinner here with you … to discuss your future plans.’

Plans? Theo feels unsure. His voice is stammering a little. ‘I … I have another year at Eton, and after that…’

‘You still have hopes for medicine? You understand there are restrictions, and that your grandfather considers the profession to be one full of charlatans and butchers?’

‘I know he views the trade as below my social status.’ He imitates the old man’s voice: ‘No one who shares the Seabrook blood will take the role of a sawbones. You might as well look for employment in the slaughterhouse at Slough.’