Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

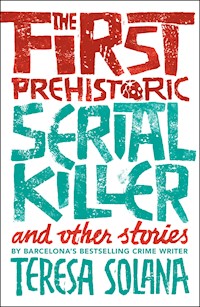

An impressive and very funny collection of stories by Teresa Solana but the fun is very dark indeed. The oddest things happen. Statues decompose and stink out galleries, two old grandmothers are vengeful killers, a prehistoric detective on the verge of becoming the first religious charlatan trails a triple murder that is threatening cave life as the early innocents knew it. The collection also includes a sparkling web of Barcelona stories--connected by two criminal acts--that allows Solana to explore the darker side of different parts of the city and their seedier inhabitants.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR

The First Prehistoric Serial Killer

“Solana has long been one of the quirkiest and most accomplished of crime writers, but this is something new: wonderfully crafted short-form fiction – often sardonic, often surreal, but always pure Solana.”

BARRY FORSHAW, AUTHOR OF EURO NOIR

“Teresa Solana’s distinctive writing is humorous yet thought-provoking, and her short fiction is as entertaining as her novels.”

MARTIN EDWARDS, AUTHOR OF GALLOWS COURT AND THE LAKE DISTRICT MYSTERIES

“Detective fiction in Spain is flourishing and Teresa Solana is one of its most accessible protagonists. Her books are superbly plotted, as well as being sharp and acerbically funny commentaries on a society still coming to terms with Franco’s dictatorship. The present collection, brilliantly translated by Peter Bush, brings together her explorations of the darker side of contemporary Barcelona and her unsettling surrealistic streak.”

PAUL PRESTON, AUTHOR OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

“The First Prehistoric Serial Killer is a delight. Teresa Solana romps through a louche Barcelona teeming with shady characters and criminal intent. Whether investigating the titular crime, smoking out a grand house’s generations of ghosts, or connecting the dots between a series of events, her signature combination of dark humour and sly social commentary informs every word. She’s aided and abetted by her usual partner in crime, translator Peter Bush, who renders her tales in sparkling English.”

SUSAN HARRIS, WORDS WITHOUT BORDERS

Born in Barcelona in 1962, Teresa Solana lives in Oxford. She has written several highly acclaimed novels. A Not So Perfect Crime, the first in the Borja and Eduard crime series, won the 2006 Brigada 21 Prize for the best Catalan crime novel. Since then, she has published five more novels. In addition to many articles and essays on translation, Teresa Solana has also written a number of children’s books.

Peter Bush is an acclaimed translator from Spanish and Catalan, known for his translations of Leonardo Padura, Juan Goytisolo and Josep Pla.

THE FIRSTPREHISTORICSERIAL KILLER

AND OTHER STORIES

Teresa Solana

Translated from the Catalan by Peter Bush

BITTER LEMON PRESSLONDON

BITTER LEMON PRESS

First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 byBitter Lemon Press, 47 Wilmington Square, London WC1X 0ET

www.bitterlemonpress.com

The Blood, Guts and Love stories were first published in Catalan as part of Set casos de sang i fetge i una història d’amor by Edicions 62, Barcelona, 2010. The stories in Connections were first published in Catalan as Matèria Grisa by Amsterdam, Ara Llibres, Barcelona, and received the Roc Boronat Prize 2017.

Versions of some of the stories in this collection have previously been published in the Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, The Massachusetts Review and Mediterraneans. ‘The Son-in-Law’ appeared in both in the Words Without Borders Best of the First Ten Years anthology and the Found in Translation anthology of the best hundred stories in world literature from Head of Zeus. Connections won the prestigious Catalan 2107 Roc Boronat prize, and ‘Still Life No. 41’ was shortlisted for the 2013 Edgar award.

The translation of this work has been supported by the Institut Ramon Llull.

©Teresa Solana 2018

English translation ©Peter Bush 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher

The moral rights of Teresa Solana and Peter Bush have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978–1–912242–07-8

eBook ISBN 978–1–912242–08-5

Typeset by Tetragon

Printed and bound in Great Britain byCPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR9 4YY

Contents

BLOOD, GUTS AND LOVE

The First Prehistoric Serial Killer

The Son-in-Law

Still Life No. 41

Happy Families

I’m a Vampire

CONNECTIONS

Flesh-Coloured People

The Second Mrs Appleton

Paradise Gained

Mansion with Sea Views

I Detest Mozart

Birds of a Feather

Barcelona, Mon Amour

But There Was Another Solution

BLOOD, GUTS AND LOVE

A first note to readers:

Can you imagine living in a house haunted by ghosts with class prejudice? Or being a prehistoric detective on the verge of becoming the first religious charlatan, investigating a triple murder that is threatening blissful cave life? Or running an art gallery where stinking statues decompose on their pedestals? These stories combine absurd humour with noir to paint a satirical portrait of the society in which we live.

Most readers and writers of noir will never commit a crime or be involved in a police investigation, and perhaps that is why we so enjoy reading and writing stories of blood and guts that allow us to enter the criminal minds of murderers and the elaborate mind games and procedures of fictional detectives. But we are all trapped in some way. No matter whether a tormented ghost, a repentant vampire, a nice-as-pie old lady or a gauche mammoth hunter, at some stage in our lives we will be forced to make a choice that will challenge our values and force us to enter the murky unknown.

The First Prehistoric Serial Killer

A number of us woke up this morning when the storm broke, only to find another corpse in the cave. This time it was Athelstan. I almost fainted the second I saw his smashed skull and his brains seeping down his temples into a pool of black blood, but the others slapped me and I came around. I rushed to rouse our chief to ask him to come and take a look and tell us what to do. Ethelred is on the deaf side and sleeps like a log, and though the men shouted, in the end we had to piss on him to get him to stir. Grumbling and bleary-eyed, our chief examined Athelstan’s body, cursing our bones for dragging him out of bed at such an early hour. In the meantime, the rain stopped and the sun began to shine.

While Ethelred and the others speculated about what had happened, I studied the bloody rock that lay a few yards from Athelstan’s corpse and suggested to Ethelred that the two might be related. Ethelred, a rather laconic troglodyte, looked at me sceptically and warned me not to jump to conclusions.

“Hold your horses,” he commented. “I want my breakfast first.”

After gobbling down fried ostrich eggs with turtle and herb sausages, Ethelred calmed his men down by insisting it must have been an accident. Then he brushed his teeth on a branch and said he’d like to speak to me in private. We surreptitiously retreated to a recess at the back of the cave so the other males wouldn’t hear our conversation, but as our cave has magnificent acoustics and you have to shout at Ethelred to make sure he hears you, everybody eavesdropped. In fact, I didn’t see the point of so much secrecy, because he soon called an assembly to inform the men, and, except for Rufus, who’s rather nosy, nobody seemed particularly interested.

Ethelred, who isn’t as stupid as he seems, asked me to open an investigation because three deaths in fourteen moons are too many and the clan was beginning to feel edgy. The fact that all three had been male and that we’d found them early in the morning with their heads smashed in with a rock was too much of a coincidence. However, cautious Rufus and Ethelred favour the accident hypothesis. For my part, I’m pretty sure something’s up in the cave. My problem is I don’t know what.

Rufus, Ethelred’s right-hand man, immediately protested at the very idea that I should lead the investigation, but Ethelred quickly landed a punch, and knocked a couple of his teeth out: end of argument. It makes a lot of sense that he’s chosen me to handle this; I am, by a long chalk, the cleverest troglodyte ever. Of the twenty males that comprise the Hairy Bear tribe (give or take a couple), I’m the only one who doesn’t stumble over the same stone every morning when I leave the cave, a phenomenon that intrigues the lot of them. The other point in my favour is that I’m the troglodyte with most free time on his hands because Ethelred has banned me from going hunting. Partly because I’m not very good at it and he prefers me to stay with the females rather than upset the hunting party. Indeed, if I hadn’t discovered fire by chance one spring evening when the other males were out shafting and I was bored stiff, they’d have probably put me six feet under and I’d be pushing up daisies in the necropolis or in some animal’s craw. After all, thinking with one’s head and not one’s feet (or that other appendage …) has its advantage, and I trust that I’ll get recognition someday.

Because of my privileged status as the idler in the tribe, I had no choice but to follow Ethelred’s orders. He’s in charge and, however much we grumble about it, this is no democracy. As the rain had stopped, the men went mammoth hunting and the women snail collecting; in the meantime, I slumped under a fig tree and activated my grey cells to find a lead to help me discover the murderer’s identity. Ethelred and Rufus can say what they like, but I am convinced there’s skulduggery afoot and we’re dealing with three murders, with a capital M.

The first to cop it was Lackland, whose head was also smashed in with a bloody stone that was then left lying next to it. Lackland was a fine fellow but daft as a brush, so we all thought it was self-inflicted and left it at that. A few moons later it was Beowulf’s turn, and since he mostly received blows to the right side of his skull, I started to think we were barking up the wrong tree. Everyone in the clan knew Beowulf was left-handed (because his right arm had ended up in some beast’s belly), so it could hardly have been suicide or an accident, which had been our theory in Lackland’s case. My suspicions were confirmed this morning when we found Athelstan’s corpse. At a glance the cause of death seems similar, but as nobody knows how to carry out an autopsy comme il faut, we can’t be sure. In the absence of scientific evidence, I must tread the slippery terrain of hypothesis where it’s easy to come a cropper. Nonetheless, I think there are three facts I can establish beyond the shadow of a doubt: firstly, all three met a violent death; secondly, someone smashed their skulls in with a rock; thirdly, it happened while they were sleeping, because we found all three on the pile of rotting leaves we call a bed.

Far be it from me to seem melodramatic, but considering that the modus operandi seems to be the same in each case, I’m beginning to think we are dealing with the first prehistoric serial killer ever. The fellow who did it has bumped off three men and we’ve yet to find him, so I deduce he must be a cold, calculating male, and brainy into the bargain.

Mid-morning the hunters returned with a couple of mammoths. There were no casualties on this occasion. After clearing it with Ethelred, I started my interrogations and spoke to every member of the tribe to see if anyone was without an alibi. Unfortunately, they all had one, because they swore to a man they were snoozing in the cave. As I’d spent the night at the necropolis reflecting on the question of existence, I realized I was the only one without a rock-solid alibi. But I’d swear I didn’t kill Athelstan. I’m almost absolutely sure on that front.

Given that everyone has an alibi, I concluded we were perhaps looking in the wrong place. Not far from our cave there’s a small hamlet of stone houses we call Canterbury because the inhabitants love cant. It’s more than likely the murderer doesn’t belong to our tribe and has come from outside. If the murderer is an outsider, the Canters are top of my list; as far as we know, they are the only prehistoric community round here. After I informed Ethelred of my conclusions, our chief decided to send out a fact-finding mission.

Ethelred, Rufus, Alfred and yours truly went to Canterbury. Initially, we were on tenterhooks, given that the Canters are practising cannibals (endocannibals is the term they use) and we were afraid they’d gobble us up before we could explain why we’d come. In the end, our fears were unfounded. The Canterbury Neanderthals are amazingly hospitable and gave us a first-rate welcome, all things being equal. They even invited us to wash in a green bath of aromatic herbs, a form of ritual ablution, but as water is not our favourite element we politely refused the bath, claiming our beliefs forbade us to wash and we were there on business. After the typical exchange of presents – an oval stone for a round one, a trefoil for an ammonite – we told Penda, their chief, what had happened in our cave and of our suspicions. He was adamant in his response.

“How on earth could the murderer be a Canter if, as you say, nobody tucked into the corpses? You know we are cannibals!” he grimaced, visibly annoyed.

“Yes, but you always reckon you practise endocannibalism, I mean you only eat your own …” I retaliated.

“In fact, we like a little bit of this and a little bit of that …” Penda confessed rather reluctantly. “However, we use more sophisticated tools and don’t go around killing people with rocks, like you do. For God’s sake, if it had been one of us, he’d have used an axe, not a boulder!”

“True enough,” I acquiesced.

“Right, let’s be off then!” roared Ethelred, springing to his feet. “That’s all cleared up, Penda, we won’t bother you any more. Do forgive us for burdening you with all our woes. Some individuals,” he added, giving me a withering look, “think they are real bloody sapiens sapiens …”

“Don’t worry,” said Penda knowingly. “Weeds prosper wherever.”

We walked back in silence, our tails between our legs (not merely metaphorically in Alfred’s case). Back in our cave, I got a tongue-lashing and savaging I couldn’t dodge. Ethelred and Rufus were livid and shouted at me in front of the women.

“We were made to look like complete fools!” Rufus spat in my face. “I don’t know what the fucking use such a brainbox is if you never get it right!”

“To err is only human,” I answered meekly.

“Come on, Mycroft, stop being such a Sherlock and get cracking. See if you can invent the axe!” added Ethelred. “We were made to look like a bunch of yokels!”

“All right, I’ll see what I can do in the morning,” I agreed.

I had no choice but to discount the outsider theory and concentrate on the inhabitants of our cave, because if the Canters are innocent, the guilty party must be one of us. After ruminating a while, waiting for the women to serve tea, I thought I’d better concentrate on discovering what the three victims, namely Athelstan, Beowulf and Lackland, had had in common, and I reached the following conclusions: a) all three were male; b) all three were hunters; c) none was immortal. Apart from that I drew a blank and couldn’t establish a motive, because the deceased were all beautiful people. Strictly in terms of their characters, I mean.

After tea, while getting ready for my nap, I thought it would be worth my while to create a psychological profile of the murderer and see if I could eliminate any suspects. The results were disappointing: the only conclusion I drew was that the guilty man is someone who can wield a rock. I could discount the children and Offa, who’s armless because a bear ate his arms one day while he was taking a siesta under a pile of branches by the cave. Not counting the three who have already passed away, there remain some fifty-three suspects, because I wouldn’t want to leave the women out or they’d be furious and accuse me of being a male chauvinist pig. Fifty-three suspects are a lot, but it’s better than nothing.

In any case, I needed to shorten my list. I retraced my steps, recalling how I’d established, quite reasonably, that the murderer must be a cold, calculating, intelligent fellow. Naturally, that led me automatically to eliminate women and children from my enquiry. I reviewed the list of males in the tribe and was basically unable to identify a single one worthy of the epithet of “intelligent”. Once more, the finger of suspicion points at me: I don’t have an alibi and am the only Neanderthal in the group whose neurons function at all. Moreover, I’m a cold customer and the only one able to calculate within a reasonably small margin of error how many tribal males are left now three have bitten the dust. I plucked up my courage and accepted the evidence: no doubt about it, I’m the murderer.

“I’ve solved the case,” I told Ethelred, who was busy carving up a mammoth. “After examining the facts, I’ve reached the conclusion that I did it.”

“What do you mean?” reacted Ethelred, putting the mammoth to one side and glowering at me.

“How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?” I declared. “Ethelred, I am the murderer.”

“Mycroft, cut the crap!” thundered Ethelred, punching a rock and breaking a couple of bones in his left hand. “How the hell could you have killed them if you faint at the sight of a drop of blood …?”

“True enough. I’d forgotten.”

“So, get on with it. If you don’t solve this case, none of us will get any shut-eye and you’re up for immolation. You do know that, don’t you?”

“No, I didn’t. It’s news to me.”

“Well, I had the idea a while back. We voted on the motion and it was passed nem. con. Sorry, I forgot to pass the news on.”

“Fair enough.”

I have the impression I’m miscuing this investigation. From the start I’ve focused on who, but perhaps if I concentrate on why the answer will come just like that. Why were Rufus, Beowulf and Athelstan in particular picked for the chop? What’s the motive lurking behind their deaths? Who stands to gain?

There’s one aspect that Lackland highlighted, and it may be worth consideration. All the males of the tribe are stressed out by the murders but the women, on the contrary, are as cool as cucumbers, as if the serial killer thing doesn’t affect them. Not even Matilda, the matriarch of the group, seems the least worried by the fact we have a head-smashing psychopath in the cave. This makes me wonder. What can’t I see? What am I missing?

We all know women have a secret: what they do to get pregnant. Do they swallow on the sly a magic root we know nothing about? Do they hoard their farts, inflate their bellies and thus create a child inside themselves? All us males are obsessed with procreation, because however much we bluster on our weekend binges, the females sit in the driving seat. If we could crack the secret behind pregnancy, the power they exert over us would evaporate. Can’t you tidy the cave? You’ve pissed up the wrong tree! The meat was tough again! They treat us like dummies, and on the pretext that they have to suckle their babes they dispatch us to get rid of the rubbish and hunt wild animals, which means we often return to the cave missing a companion or short of a limb. But there’s no way we can find out how the buggers do it.

The day before his head was smashed in, Lackland announced he’d found out their big secret: females get pregnant thanks to our white wee-wee. Of course, this is pure idiocy, and apart from Athelstan and Rufus, who are the most credulous of men, none of us gave it a second thought. I mean, if male wee-wee is what gets women pregnant … the goats and hens in the corral would also be bringing kids into the world! Those poor chaps are so simple-minded!

Even though I don’t think the women’s secret is connected to the homicides, I decided to have a word with Matilda because all this is making me feel uneasy. I told her my doubts and she immediately reassured me.

“Mycroft, don’t get your knickers in a twist, I beg you.”

“It’s just that you don’t seem scared of the psychopath in the cave. At the very least, it’s a little odd …”

“So you want to be the next to appear one morning with his head smashed in, do you?” she asked, picking up a rock.

“Of course I don’t … But if I don’t find the guilty party, they’re going to immolate me at the crack of dawn. You know how pernickety old Ethelred is …”

“Sit down and listen to me, then,” she said with a sigh. “This is what you must tell Ethelred and his band of rogues.”

As Matilda isn’t short of spunk and is more than able to send an adult male flying from one end of the cave to another, I sat obediently by her side and listened to her most rational explanations. Given her excellent aim when sling-hunting bats, I found her arguments entirely persuasive. I immediately went to see Ethelred to tell him a second time that I’d solved the case.

“Beowulf, Lackland and Athelstan were punished by the gods because they discovered something they weren’t supposed to know,” I affirmed smugly.

“And what might that be?” asked Ethelred offhandedly.

“The women’s secret. The child thing …”

“Oh …!” Ethelred scratched his private parts with his nails and out jumped a couple of fleas. “And who the fuck might these gods be?”

“Gods are superior beings who rule the universe,” I answered, making it up as I went along. “They are eternal, almighty and immortal. From up in the sky where they live, they see all and know all.”

“How do you know?” he enquired, looking at me like a dead fish.

“I had a vision in my dreams. I was told that if we stop trying to find out what women do to get with child there will be no more deaths.”

“What good news!” exclaimed Ethelred, squashing another flea. “Case closed! Now let’s dine. I’m so hungry I could eat a diplodocus!”

And added, with a grin, winking his only eye at me, “If they weren’t extinct, I mean …”

I can’t complain. Today I’ve solved three murders and in one fell swoop invented prophecies, gods and oneiromancy. And saved my own skin into the bargain. The only thing worrying me now is that henceforth everybody will be badgering me to interpret their dreams and will have the cheek to want me to do it for nothing. I can see it now: “I’m having erotic dreams about my mother or dream of killing my father.” Or, “Yesterday I dreamt Cnut’s menhir was bigger than mine …” You know, perhaps I should consider inventing psychoanalysis. It’s not as if I have anything better to do.

The Son-in-Law

The mossos came this morning. I’d been expecting them for days.

When I opened the door, they were still out of breath. That’s nothing unusual. Visitors all get to my attic flat on the seventh floor on their last legs: there’s no lift. The stairs are steep and they’re an effort to climb, and instead of taking it calmly, like Carmeta and me, they must have pelted up like lunatics. I reckon their uniforms will have set the neighbours’ tongues wagging; there are a number of pensioners with nothing better to do than look through their spyholes at my staircase. I only hope the mossos don’t decide to question them, because my neighbours love to stir things. In any case, I don’t think they suspect any funny business.

There was a man and a woman, nice and polite they were, and she was much younger. My hair was tangled, I wasn’t made up and was wearing the horrible sky-blue polyester bathrobe and granny slippers I’d taken the precaution of buying a few days ago at one of the stalls in the Ninot market. The bathrobe is very similar to the one worn by Conxita, the eighty-year-old on the second floor, but it looked too new so I put it through the washing machine several times the day before yesterday so it was more like an old rag, which is how I wanted it to look. Now the bathrobe was frayed and flecked with little bobbles of fluff, and, to round off the effect, I spilled a cup of coffee I was drinking over my bust. The woman tactfully scrutinized me from head to toe, dwelling on the stains and dishevelled hair, and I was really lucky one of the police belonged to the female sex since we ladies take much more notice of the small details than the menfolk do. She seemed very on the ball and I trust she drew her own conclusions from my shabby appearance.

Her colleague, fortyish and with Paul Newman’s eyes, was the one in charge. He introduced himself very nicely, asked me if I was who I am and said he just had a few questions he wanted to ask. A routine enquiry, he added, smiling soothingly. I’d nothing to worry about. I adopted the astonished expression I’d been rehearsing for days in front of the mirror and invited them into the dining room.

As they followed me down the passage, I made sure I gave them the impression I was a frail, sickly old dear struggling to walk and draw breath. I exaggerated, because I’m pretty sprightly for my age and, thank God, I’m not in bad health, although I tried to imitate the way Carmeta walks, dragging my feet at the speed of a turtle, as if every bone in my body was aching. Both homed in on the sacks of cement, the tins of paint and workmen’s tools that are still in the passage, and asked me if I was having building work done. I told them the truth: that after all that rain, the kitchen ceiling had collapsed and it had been a real mess.

“If only you’d seen it …! You’d have thought a bomb had dropped!” I told them with a sigh. “And it was so lucky I was watching the TV in the dining room …!”

The young policewoman nodded sympathetically and said that was the drawback with top-floor flats, though an attic has lots of advantages because you get a terrace and plenty of light. “What’s more,” she added shyly, “with all the traffic there is in the Eixample, you don’t hear the noise from the cars or breathe in so many fumes.” I agreed and told her a bit about what the Eixample was like almost fifty years ago, when Andreu and I first came to live here.

Visibly on edge, her colleague interrupted and asked me if I’d heard anything from my son-in-law. I adopted my slightly senile expression again and said I hadn’t.

The policeman persisted. He wanted to know the last time I’d seen Marçal and if I’d spoken to him by phone. I told him as ingenuously as I could that I’d not heard from him for some time, and politely enquired why he was asking.

“He disappeared a week ago and his family think something untoward may have happened. That’s why we’re talking to everyone who knows him,” he replied softly. “I don’t suppose you know where he’s got to, do you?”

“Who?” I said, pretending to be in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

“Your son-in-law.”

“Marçal?”

“Yes, Marçal.”

“Sorry … What was it you just asked me?”

Like those old people who really don’t cotton on, I changed the subject and asked them if they’d like a drink – a coffee, an infusion or something stronger. When they asked me if I knew that he and my little girl were negotiating a divorce and if I was aware my son-in-law had a restraining order in force because she’d reported him for physical abuse, I simply looked at the floor and shrugged my shoulders. Reluctantly, I confessed I suspected things weren’t going too well.

“But all married couples have problems … I didn’t want to harp on about theirs,” I said, adding, “Nowadays women don’t have the patience … In my time …”

I didn’t finish my sentence. There was no need. The young policewoman looked at me affectionately and gave one of those condescending smiles liberated young females of today reserve for us old wrinklies with antiquated ideas. Out of the corner of one eye, I registered that she’d had a French manicure and wore a wedding ring. To judge by her pink cheeks and smiley expression, the young woman must still be in the honeymoon period.

Before they could start grilling me about Marçal and his relationship with Marta again, I began to gabble on about stuff that was totally unrelated, playing the part of an old dear who lives by herself, has nobody to talk to and spends her day sitting on her sofa in front of the TV watching programmes she doesn’t understand. My grousing made them uneasy, and the man finally glanced at his watch and said they ought to be leaving. Their visit (you couldn’t really call it an interrogation) had lasted less than ten minutes. When they were saying goodbye, they repeated that I shouldn’t worry. That it was probably just a misunderstanding.

Marta, my little girl, will soon be thirty-six. I’m seventy-four, and it’s no secret that Andreu and I were getting on when I got pregnant with Marta. Nowadays it’s quite normal to have your first baby at forty, but it wasn’t in my day. If you didn’t have a bun in the oven before you turned thirty, people scowled at you, as if it was a sin not to have children. The kindest comment they’d make was that you weren’t up to it. If you were married and childless, you suddenly became defective.