11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

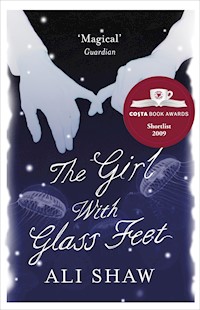

Winner of the Desmond Elliott Prize (2010) Shortlisted for the Costa Book Award Nominee for First Novel (2009) Longlisted for Guardian First Book Award (2009) Longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize (2010) Shortlisted Tähtifantasia Award Nominee (2012) A mysterious metamorphosis has taken hold of Ida MacLaird - she is slowly turning into glass. Fragile and determined to find a cure, she returns to the strange, enchanted island where she believes the transformation began, in search of reclusive Henry Fuwa, the one man who might just be able to help... Instead she meets Midas Crook, and another transformation begins: as Midas helps Ida come to terms with her condition, they fall in love. What they need most is time - and time is slipping away fast.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

The girl with glass feet

Ali Shaw was born in 1982 and grew up in a small town in Dorset. He studied English at Lancaster University and has since worked as a bookseller and at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. He is currently writing his second novel.

Copyright

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Ali Shaw, 2009

The moral right of Ali Shaw to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-84354-920-8

Contents

Cover

The girl with glass feet

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Acknowledgments

1

That winter there were reports in the newspaper of an iceberg the shape of a galleon floating in creaking majesty past St Hauda’s Land’s cliffs, of a snuffling hog leading lost hill-walkers out of the crags beneath Lomdendol Tor, of a dumbfounded ornithologist counting five albino crows in a flock of two hundred. But Midas Crook did not read the newspaper, he only looked at the photographs.

That winter Midas had seen photos everywhere. They haunted the woods and lurked at the ends of deserted streets. They were of such multitude that while lining up a shot at one, a second would cross his aim and, tracking that, he’d catch a third in his sights.

One day in mid-December he chased the photos to a part of the woods near Ettinsford. It was a darkening afternoon whose final shafts of light passed between trees, swung across the earth like searchlights. He left the path to follow such a beam. Twigs crunched beneath his shoes. A bleating bird skipped away over leaves. Branches swayed and clacked against each other overhead, snipping through the roving beam. He kept up his close pursuit, treading through its trail of shadows.

His father had once told him a legend: lone travellers on overgrown paths would glimpse a humanoid glow that ghosted between trees or swam in a still lake. And something, some impulse from the guts, would make the traveller lurch off the path in pursuit, into the mazy trees or deep water. When they pinned it down it would take shape. Sometimes it would form a flower of phosphorescent petals. Sometimes it drew a bird of sparks whose tail feathers fizzed embers. Sometimes it became like a person and they’d think they saw, under a nimbus like a veil, the features of a loved one long lost. Always the light grew steadily brighter until – in a flash – they’d be blinded. Midas’s father hadn’t needed to elaborate on what happened to them after that. Lost and alone in the cold of the woods.

It was nonsense, of course, like everything his father had said. But light was magic, making the dull earth vivid. A shaft of it hung against a tree trunk, bleaching the cracked bark yellow. Enticed, Midas crept towards it and captured it on camera before it sank back into the loam. A quick glance at his display screen promised a fine picture, but he was greedy for more. Another shaft lit briars and holly ahead. It made the berries sharply red, the leaves poisonously green. He shot it, and harried another that drifted ahead through the undergrowth. It gathered pace while Midas tripped on roots and snagged his ankles on strands of thorns. He chased it all the way to the fringe of the wood, and followed it into the open, where the scrubland sloped down and away from him towards a river. Crows wheeled in a sky of oily rags. Hidden water gurgled nearby, welling into a dark pool at the bottom of the slope. Above the pool, the ray of light dangled like a golden ribbon. He charged down the slope to catch it, feet skidding on mushy soil and sharp air driving into his lungs as he stumbled the last distance down to the banks. A sheet of lacy ice covered the water and prevented reflections, so all he could see in the pool was darkness. The ray had vanished. The clouds had coalesced too fast. He was panting, hanging his head and resting with hands on knees. His breath hung in the air.

‘Are you okay?’

He spun around and felt his foot skid on a clot of soil. He fell forward and stumbled up again with filthy hands and cold muddy patches on his knees. A girl sat neatly on a flat rock. Somehow he’d not seen her. She looked like she’d stepped through the screen of a 1950s movie. Her skin and blonde hair were such pale shades they looked monochrome. Her long coat was tied at the waist by a fabric belt. She was probably a few years younger than him, in her early twenties, wearing a white hat with matching gloves.

‘Sorry,’ she said, ‘if I surprised you.’

Her irises were titanium grey, her most striking feature. Her lips were an afterthought and her cheekbones flat. But her eyes… He realized he was staring into them and quickly looked away.

He turned to the pond in hope of the light. On the other side of the water was a field marked out by a stringy barbed-wire fence. A shaggy grey ram stood there, horns like ammonites, staring into space. Past that the woods began again, with no sign of a farmhouse attached to the ram’s field. Nor was there any sign of the light.

‘Are you sure you’re okay? Have you lost something?’

‘Light.’

He turned back to her, wondering if she might have seen it. It was on the rock beside her, beamed through a hole in the clouds.

‘Shh!’ He spent half a second aiming, then took the shot.

‘What are you doing?’

He scrutinized the image on the camera’s screen. A fine photo, all told. The girl’s half of the stone steeped in a tree’s forked shadow, the other half turned to a hunk of glowing amber. But wait… On closer examination he had made a mess of the composition, cropping the ends of her boots. He bent closer to the screen. No wonder he had made the mistake, for the girl’s feet sat neatly together in a pair of boots many sizes too big for her. They were covered in laces and buckles like straitjackets. A walking stick lay across her lap.

‘I’m still here, you know.’

He looked up, startled.

‘And I asked you what you were doing.’

‘What?’

‘Are you a photographer?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’re a professional?’

‘No.’

‘Amateur?’

He frowned.

‘You’re an unemployed photographer?’

He waved his hands in vague directions. This complicated question often worried him. What other people could not realize was that photography wasn’t a job, a hobby or an obsession; it was simply as fundamental to his interpretation of the world as the effect of light diving in his retinas.

‘I cope,’ he mumbled, ‘with photography.’

She raised an eyebrow. ‘It’s rude to photograph people without their consent. Not everyone enjoys the experience.’

The ram grunted in its field.

She carried on. ‘Anyway, may I see it? The photograph you took of me.’

Midas timidly held out the camera, tilting it slightly towards her.

‘Actually,’ he explained, ‘um, it’s not a photo of you. If it were I’d have framed it differently. I wouldn’t have cropped the tip of your, erm, boots. And I’d have asked permission.’

‘Then what’s it a photograph of ?’

He shrugged. ‘You could say it was the light.’

‘Can I take a closer look?’

Before he’d had a chance to figure out how to word a sentence to say no, not really, not quite, he wasn’t that comfortable with other people handling his camera, she reached up and took it. The carry strap, still slung around his neck, forced him to step unbearably close to her. He winced and waited, leaning backwards to keep as much of himself as far as he could from her. His eyes drifted back to her boots. They weren’t just big. They were enormous on a girl so thin. They reached almost up to her knees.

‘God, I look awful. So shadowy.’ She sighed and let the camera go. Midas straightened up and took a relieved step backwards, still staring at her boots.

‘They were my dad’s. He was a policeman. They’re made for plodding.’

‘Oh. Ah…’

‘Here,’ she opened her handbag and took out her wallet, finding inside a dog-eared piece of photograph showing her in denim shorts, yellow T-shirt and sunglasses. She stood on a beach Midas recognized.

‘That’s Shalhem Bay,’ he said, ‘near Gurmton.’

‘Last summer. The last time I came to St Hauda’s Land.’

She offered him the photo to take a closer look. In it, her skin was tanned and her hair a roasted blonde. She wore a pair of flip-flops on small, untoward feet.

A snort behind him made Midas jump. The ram had made a steamy halo for its horned head.

‘You’re quite a jumpy guy. Are you sure you’re all right? What’s your name?’

‘Midas.’

‘That’s unusual.’

He shrugged.

‘Not so unusual if it’s your own name, I suppose. Mine’s Ida.’

‘Hello, Ida.’

She smiled, showing slightly yellowed teeth. He didn’t know why that should surprise him. Perhaps because the rest of her was so grey.

‘Ida,’ he said.

‘Yes.’ She gestured to the speckled surface of the rock. ‘Do you want to sit down?’

He sat a few feet away from her.

‘Is it just me,’ she asked, ‘or is this an ugly winter?’

The clouds were now as thick and drab as concrete. The ram rubbed a hind leg against the fence, tearing its grey wool on the barbed wire.

‘I don’t know,’ Midas said.

‘There’ve been so few of those crisp days when the sky’s that brilliant blue. Outdoor days I like. And the dead leaves aren’t coppery, they’re grey.’

He examined the mush of leaves at their feet. She was right. ‘Pleasing,’ he said.

She laughed. She had a watery cackle he wasn’t sure he enjoyed.

‘But you,’ he said, ‘are wearing grey.’ And she looked good. He’d like to photograph her among monochrome pines. She’d wear a black dress and white make-up. He’d use colour film and capture the muted flush in her cheeks.

‘I used to dress in bright colours,’ she said, ‘saffrons and scarlets. Jesus, I used to have a tan.’

He screwed up his face.

‘Well, you were always bound to enjoy black-and-white winters. You’re a photographer.’ She reached over and shoved him playfully in a way that stunned him and would have made him shriek if he weren’t so surprised. ‘Like the wolf man.’

‘Um…’

‘Seeing in black and white like a dog. As for me, I like colourful winters. I really want them to return. They were never this dreary before.’

She kept her feet still as she sat, not shuffling them about and poking at the ground as he had a habit of doing.

‘So what do you do? If you’re not a professional photographer?’

He remembered from nowhere what his father had said about never talking to strangers. He cleared his throat. ‘I work for my friend. At a florist’s. It’s called Catherine’s.’

‘Sounds fun.’

‘I get paper cuts. From the bouquet paper.’

‘A florist must be a nightmare for a black-and-white photographer.’

The ram hoofed at slushy dirt.

Midas gulped. These had been more words than he had spoken in some weeks. His tongue was getting dry. ‘What about you?’

‘Me? I suppose you could say I’m unemployable.’

‘Um… Are you ill?’

She shrugged. A fleck of rain hit the rock. She smoothed her hat further on to her head. Another raindrop fell on the leather of one boot, making a reflective spot above the toes.

She sighed. ‘I don’t know.’

More rain fell icy on their cheeks and foreheads.

Ida looked up at the sky. ‘I’d best head back.’ She picked up her walking stick and carefully pushed herself to her feet.

Midas looked back up the slope he’d charged down. ‘Where’s… back?’

She gestured with her stick. Away down a winding river-bank path. ‘A little cottage that belongs to a friend.’

‘Ah. I suppose I’d best be going, too.’

‘Nice to meet you.’

‘And you. Get… Get well soon.’

She waved gingerly, then turned around and moved away along the path. She walked at snail’s pace, cautiously placing her stick before each step, like she was rediscovering walking after a bedridden spell. Midas felt a tug inside him as she left. He wanted to take a picture, photograph her this time, not light. He hesitated, then shot her from behind, her shuffling figure back-dropped by the water and the ram’s grey field.

2

She’d developed a particular way of walking to accommodate her condition. Step, pause, step, instead of step, step, step. You needed that moment’s pause to make sure you’d set your foot straight. Like the opening gambits of a dance. Her boots were thick and padded, but one accidental fall or careless stumble could do irreparable damage that would finish her off for good, she supposed. That would be that.

And what was it like, walking on bone and muscle, on heels and soles? She couldn’t remember. Now walking felt like levitation, always an inch off the ground.

The river stayed quiet, here pattering down a short cascade, there brushing over a weed-covered rock that looked like a head of green hair. Ida kept hobbling, occasional raindrops dissolving into her coat and making the wool of her hat wet. That was another problem with this bloody stupid way of getting about: you couldn’t move fast enough to keep warm. She pulled her scarf over her chin and ice-cold nose.

Thickets of holly dipped branches in the river. A moth landed on a cluster of bright berries. She stopped walking as it fanned its wings. They were furred brown and speckled with lush greens.

‘Hi,’ she said to the moth.

It flew away.

She walked on.

She wanted the moth back. Sometimes when she closed her eyes she saw more colour than she could in a whole day on St Hauda’s Land with them open.

She had always liked to be in places where tightly packed hips, shoulders and backsides danced against yours, a dazzle of colours whirling on dresses and shirts. She’d held off sleep using the sheer pleasure of company, be it huddled in a freezing tent wearing a thick jumper or trading stories over card games in friends’ flats until morning came. There was none of that to be had on these islands.

She had with her the tatty St Hauda’s Land guidebook she had bought on her trip to the archipelago in the summer. When she had opened it that winter, for the first time since the trip, grains of white sand fell from its spine.

She’d had more enthusiasm for the place in summertime. She had read, with pity for the islanders, about the lurching industrial fishing boats that trawled from the mainland to intrude in the archipelago’s waters, scooping whole pods of speared whales from the water and turning them to blubber and red slop on their slaughterhouse decks. She had read of local whalers who sailed farther and farther out to sea in little boats their fathers and grandfathers had fished in. Some had not returned, either when storms blew up or generations-old vessels failed them. She had read of how, when they returned with dismal catches, the market was already saturated by the meat from the mainland. Whaling families began to move away, taking their youngsters with them. Ida’s guidebook tried to draw a line under this, but sounded delirious instead. Tourists would never be attracted, as the authors hoped, by the drab architecture of Glamsgallow’s seafront. Nor by the plain rock walls of Ettinsford’s church. Nor by the fishery guildhall at Gurmton, whose painted ceiling of seamen and sea creatures, all depicted with underwhelming skill in the muted colours of the ocean, was optimistically compared to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

It was wrong to count on the landscape, although it could be impressive at times. Other island destinations had more dramatic coastlines than St Hauda’s Land, which showcased more than anything the insidious sea. Ida had wondered when the guidebook’s map was sketched, for entire beaches shown on it were these days buried under the weight of water. An impressive natural rock tower called Grem Forst (known locally as the Giant’s Lamphouse) was described in flowery prose as a star attraction. The lumberjack sea had been at work, cutting away at the rock with its adze of waves. Unwitnessed one evening, the Lamphouse toppled. It broke into a string of boulders peeking meek faces out of the tide.

Inland, the archipelago had only foul-smelling bogs and haggard woodland to attract holidaymakers. Ida doubted the islands could survive the peddling of this kind of tourism. If anything, the guidebook should trumpet the one thing it was careful to avoid.

Loneliness. You couldn’t buy company on St Hauda’s Land.

He’d been an odd one, that boy with the camera. Such a distinctive physique: pale skin so taut on his skeleton, holding himself with a shy hunch, not ugly as such but certainly not handsome, with a demeanour eager to cause no trouble, to attract no attention.

Made sense. She reckoned photographers wanted you to behave as normal, as if they and their cameras weren’t there.

She liked him.

She hesitated, taking her next careful step along the river path. There were more pressing things than one skewed island man. Like finding Henry Fuwa, her first skewed island man.

Henry Fuwa. The kind of man who was either pitied or scoffed at. The kind of person who might be seen on a bus paired with the only empty seat, while passengers chose to stand in the aisle. A man she had come back all this way – braved the heaving sigh of the ferry deck and the retreat of colour – to pin down. Out of everyone she’d met since what was happening started happening to her, only Henry had offered any clue about the strange transformation beneath her boots and many-layered socks. She had not even known it was a clue when he offered it, because back on that summer trip she had still been able to wriggle her toes and pick the sand out from between them.

Wind stirred the branches of the firs overhead. The memory of the clue he had given her was like a dripping tap in the dead of night. The moment you blocked out the dripping, you realized you’d done so, and that made you listen again.

He had said it in the Barnacle, that ugly little pub in Gurmton, six months ago when the earth was baked yellow and the sea aquamarine.

‘Would you believe,’ he had said (and back then she had not), ‘there are glass bodies here, hidden in the bog water?’

Night mustered in the woods. Shadows lengthened across the path and Ida could barely see where track ended and root began. The half-moon looked like it was dissolving in the clouds. A bird called out. Leaves rustled among worm-shapes of trunks. Something shook the branches.

She hobbled onward in the dark, eager to be inside, to root out colours in the safety of the cottage. Tomorrow she would look again for Henry Fuwa. But how did you find a recluse in a wilderness of recluses?

3

After meeting Ida, Midas dawdled back to his car, scrolling through his camera’s image bank as he walked. The photos of the light shafts had worked wondrously, but he’d lost all interest in those. Both Ida pictures were awful. In the first, on the rock, she looked too shadowy. In the second, where she walked carefully away down the path, she looked plain and her boots clumsy. By the time he got back to his home in Ettinsford he’d deleted all the photos of her.

Ettinsford was one of the few settlements on St Hauda’s Land whose population was dwindling, rather than plunging to desertion. Families on St Hauda’s Land had always been whalers, ever since (it was said) a fatigued Saint Hauda drove his staff into the water at Longhem and was rewarded with the plump corpse of a narwhal calf, whose fire-charred meat kept his mission from starvation. The whaling ban of a decade back ended all that, and with the loss of the whaling families the coastal towns were falling empty. Built on slopes sinking away from the woods on both sides, Ettinsford’s roads led steeply down to a wide body of water, whose banks were designated as parkland due to regular floods rather than the need for green space. On the other side of the river the wooded slopes rose steeply. All attempts to build on these had failed. Root-infested soil gave way under houses, bricks and mortar collapsed and rolled down to splash into the water.

The town had a grocer, a fishmonger and a clutter of specialist shops with haphazard opening hours, since trade in Ettinsford happened mostly on market days and market days alone. There were two churches, one a whitewashed shack beloved of Midas’s mother before she moved to Martyr’s Pitfall on Lomdendol Island, the other an old stone chapel, the church of Saint Hauda.

Midas pushed open the gate of his front yard and walked up the path to the door of his narrow, slate-built house. Winter had perished most of the weeds but he kicked a nettle off the path while patting down his pockets for his keys. He went straight through to the kitchen, turned on the kettle and slumped into one of the wooden chairs there. Coffee rings patterned the white table. On its underside hung handfuls of sticky tack like chewing gum under a school desk, convenient when he needed to stick up a picture. He wished he had a perfect picture of Ida.

The kitchen walls were a hedgerow of black-and-white photographs. Landscapes, strangers, loved ones. A picture of a man trying to ride a bike without tyres, a mongrel cat nursing a baby pit bull to its teat, a burning boat, a streaker at a bullfight. In the only photo of himself, Midas’s hair stuck up like a crow’s wing in the wind while he helped his mother up a frosty hillside. There was another photo of his mother, hanging beside the sole picture of his father. Once he had used his computer to join them together and make it look like they were happy. He couldn’t make it real.

The kettle wheezed and clicked off. He got up, found the cafetière and rinsed his cracked white mug. Then he crouched by the fridge to get the coffee out of the freezer compartment.

Denver had stuck one of her narwhal sketches to his fridge door. He closed his eyes and took a deep breath. He’d asked her to stop sticking things there. She still did it. Hard to get cross with her when she was only just turned seven and had taken the time to sketch him such a beautiful narwhal. But sometimes Midas suspected that life was a film with subliminal messages. Things would move along with an acceptable degree of predictability, then be punctuated by some horrible childhood memory. He was in the kitchen. He had found the cafetière. He was going to open the freezer for the coffee. Then all at once he was finding his father’s suicide note on the door of another fridge, some ten or twelve years ago.

He carefully unpeeled Denver’s sketch. She’d have come around to see him and let herself in. He hoped she’d had an okay time at school. He hoped those other girls hadn’t been cruel to her that day.

He found the coffee and spooned some into the cafetière, then added water.

Something about Ida had caught him off guard. Not just her boots, her hair, her face. It was that strange thing… The way the real Ida was somehow more alluring than the filmic one.

Old-fashioned film could fix that problem.

If he had a second chance to shoot Ida, with real film, he’d get a good picture. He knew he could. The digital camera was dimming his instincts. If only he could shoot Ida somewhere brighter: set up lamps, umbrella reflectors, everything.

He plunged the filter through the cafetière. Coffee swirled inside.

But she would be company, and he was steering clear of company. It was his recurring New Year’s resolution, and it would seem a shame to break it now December was upon him. Besides, he didn’t have enough intact heartstrings to hand them to people to pull. Ever since he’d split up with Natasha (that was a long time ago now) he’d been chaste, alone. The occasional afternoon with Denver and her daddy, Gustav. All those evenings with only a camera for company.

It lay on the table with its crappy shots inside. He’d removed the lens cap to clean the glass beneath. The lens gleamed.

He enjoyed being alone.

4

Six months ago, Ida had seen Henry Fuwa lope across a cobbled road. She didn’t know him then, didn’t know anyone on St Hauda’s Land. Just a tourist enjoying some summer sun. All she had known for certain was that there’d be a collision. Henry Fuwa was so focused on his jewellery box he didn’t lift his head to look out for traffic. A cyclist, puffing downhill towards the seafront, yelled as his brakes squealed and his wheels juddered over cobblestones. He was tossed through the air by the impact, the bike upending and clattering into the road with its front wheel spinning. Henry fell backwards with his breath knocked out of him. His jewellery box flew up, turning and opening. He groped after it, then it dropped to the ground where the lid snapped clean from the hinges and the contents scudded into the gutter.

Ida sprang forward to check that both men were okay. Henry pushed his large pair of spectacles back on to his face and crawled towards his smashed box, but before he could reach its scattered contents the cyclist, who had groaned to his feet, hauled him up by the collar and snarled, ‘What the fuck do you think you’re doing?’

Ida, trying to be helpful, crouched to scoop up the box’s contents. A little nest of straw, a square of silk and some kind of dried bug, which she picked up with finger and thumb.

It had butterfly wings, like flakes of patterned wax. Under the wings it had a hairy body with tiny horns. Its fur looked very dry in the hot summer rays. It had an ox’s head, no bigger than her thumbnail, with a pink muzzle drawn into a grimace. A white splodge between its nostrils. The impossible detail of a scar on its bottom lip.

There was warmth and a heartbeat in its body like that of a newly hatched chick.

She shook her head and came to her senses. She could no longer feel the heartbeat. She must have imagined it. Likewise she had imagined the warmth of its breath on her fingers, and the rolling back of its eyes in their sockets. It must be a toy, some kind of ornament.

She looked up with a start when she heard a shout of grief. Henry Fuwa was shoving off the angry cyclist and barging towards her. He snatched the little ornament from her hands and cupped it in his, bowing his head of shaggy hair. His legs buckled under him and he fell to his knees on the cobbles. Tears dripped down the inside lenses of his glasses like droplets down a windowpane. The cyclist stormed away with his bike. Henry Fuwa gathered up the broken jewellery box and laid the ornament inside. He tugged at his beard, moaned, thumped both fists on the road. His shoulders jerked up and down so hard the vertebrae in his bowed neck showed, quivering. A pedestrian skirted wide around him and hurried on her way, but Ida, not knowing what else to do, crouched down and put a hand on his shoulder.

The road became hushed, the only sounds the distant sea, the tiptoe of gulls’ feet on the eaves of square houses and the snivelling of Henry Fuwa. He was a tall man, even knelt on the cobbles. In his late forties, she’d guess, with a smell about him, not unpleasant, like moist soil.

Ida looked down the road at a pub sign hanging over a doorway. The Barnacle, with a painting of a shipwreck for its sign. She squeezed his shoulder.

‘Come on,’ she soothed, ‘come on. Why don’t you stand up? Why don’t we go inside? I’ll buy you a drink.’

‘It’s dead,’ he said.

She slipped her arm under his and helped him up, then led him like a child into the pub.

When she had booked her summer holiday on these islands, this little archipelago thirty miles north-west of the mainland, she had reserved two seats on the ferry, one for herself and one for her boyfriend. Then he had dumped her. With a week to go, everything booked in her name, and a forecast of gorgeous summer sun, she took the trip anyway. She enjoyed stretching her legs on the hotel bed, flexing her toes in both bottom corners of the mattress. Not that she’d have been getting terribly intimate if her ex had been there. The boy was the offspring of a preacher mother and a policeman father. Their first conversation sparked from that: how to get by when your parents represented not only domestic law, but between them the laws of the state and the soul. Her own dad had been a lay preacher as well as a copper, so she sympathized. Her mother, thank heavens, had been something of a smuggler, which had helped to ensure that Ida escaped the inhibitions her ex struggled with. Mouth the word sex to him and his neck would retract like a turtle’s into its shell. His teeth would grit, his eyes would bow.

She guiltily found she didn’t miss him as much as she missed company in general. In most places she’d travelled to she’d quickly found like-minded people with whom to chat long hours away, and socializing had become a vocation. On St Hauda’s Land she found only cautious, secretive people, well-mannered but closed to strangers. In the evenings the little towns and villages became deserted and deathly quiet, but this far north in the world the summer sun didn’t sink until late, and even then light loitered. A summer day here was a long time to spend on your own.

She led Henry Fuwa to a corner table of the Barnacle, where tracks of dried bitter stained beer mats. She sat him on a stool and asked him what he’d like to drink. He shrugged.

‘Come on,’ she said, ‘it’s on me.’

‘Ugh… ’ he wiped his eyes with his wrists. ‘A gin, if you please. Just a neat single gin with ice.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘Henry Fuwa.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Henry Fuwa. I’m Ida Maclaird.’

He dried his glasses on a tatty sweater. ‘Thank you for your kindness, Ida.’

The Barnacle’s landlady leant one flabby arm on the bar while the other gesticulated in time with blurred vowels as she held forth to two regulars. The regulars sat on stools at the bar, dressed in short trousers and identical pairs of red socks stitched with white anchors. Pictures of St Hauda’s Land’s football team through the ages hung in chronological order along the walls. A sepia band of moustachioed, felt-cap-wearing gents morphed slowly down the years into a mix of spiky-haired and gap-toothed lads dressed in the club’s ice-blue strip.

The jukebox played guitar solos from the seventies, and Ida thought how badly aged some of the tracks sounded, trapped like flies in the jam jar of the pub. Broken air-conditioning snored behind the bar and did nothing about the muggy summer. She glanced back at the table where Henry Fuwa sat motionless with his head in his hands.

She wondered what her ex would make of this, proposing drinks with oddballs off the street. She sometimes wished she possessed the flawed kind of taste that drew girls to arseholes who wanted that one thing alone. You knew that kind of guy, that breed of ox-necked brute who would not be averse to wearing the same football shirt every day of the week. Who had a glamour model screensaver that made him fiddle in his pants each time it was displayed.

Not that this was a romantic endeavour. This guy was nearly as old as her dad. She took a long draught of her lager while she waited for Henry’s gin to be served.

She wasn’t that kind of girl. Instead (at times it seemed uncontrollably) she went after blokes who were wound into knots over who they were and how they tied into the world. The first time she’d lured her ex to a restaurant it had been all she could do to snap him out of the reverie he entered, only for him to emerge spouting nonsense about how she was a princess, a goddess, even a fucking mermaid one time he called her.

And now he had ditched her. He was too introverted for her, he’d said, swallowing between every word. Sweet idiot. A girl like you shouldn’t be hanging out with a guy like me. I’m worried I’m holding you back.

She carried the drinks to the table. Henry Fuwa looked a little more composed. He rubbed his sleeve across his nose.

‘So,’ she began, ‘are you from around here?’

‘Some miles away. But I live on St Hauda’s Land, yes.’

‘Did you make that ornament? Is that why you’re sad? A lot of work went into it, I bet.’

‘No. It was an old jewellery box that belonged to my mother.’

‘I mean… the figurine inside. Did you make that?’

His lips began to wobble again.

‘It was a kind of music-box, right? Such a shame. I thought it was pretty. How did you get the wings to stay attached to the little bull’s body?’

He studied her for a moment, then gave a dejected shrug. ‘I raised it.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘But the most unfortunate thing happened. They like to fly down to the water – to the beach near where I keep them. If they ever escape I know that’s where they’ll head. It’s the salt, or something in the make-up of the ocean. They weigh very little, you see. Little enough to stand on the surface like that fruitfly floating in your beer.’

The sight of the bug, all six legs cycling in the dissolving head of her drink, distracted her for a moment from her incredulity.

‘But yesterday… the tide was in. And there were jellyfish in the shallows. The bull in that box landed on the surface and, as I explained, they love to…’ He ran his hands through his hair and stared ashen-faced into his gin.

She fished out the fruitfly and wiped it on to her beer mat.

He started up again. ‘The sting… it received… People don’t always recover from jellyfish attacks, so what hope is there for a moth-winged bull? My last resort was a clinic down by the seafront, set up to treat jellyfish victims. I would have had to explain everything but…’

He took an unpractised slurp of his gin and put it back down with a lick of his lips.

She had yet to decide whether he was lying (to try to impress her?) or just nuts. The latest tune from the jukebox was a tedious soppy love song. She sipped her lager. ‘I take it this… moth-winged bull… was the only one in existence?’

‘No. There are sixty-one in known existence. All back at my pen. Sorry… There are only sixty now.’

‘That’s… incredible.’

She knew he could tell she didn’t believe him. He shrugged gloomily. ‘They eat and shit and get themselves killed like everything else.’

‘And you’re the only person in the world who knows about them?’

‘They’re my secret.’ He took a longer sip of his gin and blinked hard as he swallowed it, his expression describing the descent of the alcohol in his throat. She wondered when he’d last had a drink, then wondered if he were plain drunk. He leant across the table as earnest as hobos she’d seen in her dad’s police cells.

‘Would you believe there’s an animal in the woods who turns everything she looks at pure white?’

She sighed. ‘No. I don’t. Believe it.’

He leant back, scratching his beard. Then he tried leaning forward again. ‘Would you believe there are glass bodies here, hidden in the bog water?’

‘No. You’ve got black hair and a healthy complexion for one thing.’

‘I don’t see what that’s got… Ah, wait. I didn’t say she’d seen me.’

She watched his eyes boggle as he drained the gin. He held a hand to his forehead and wagged his finger. ‘You bought me a double…’

‘What kind of animal is she?’

‘She’s white all over, as you’d expect, except for on the back of her head where she can’t see herself.’

Ida had been through three fingers of her pint in the space it had taken him to finish his glass.

‘What colour?’

‘White.’

‘What colour’s the back of her head?’

‘Blue.’

She smiled sweetly. ‘What do you do for a living, Henry?’

‘I’m too occupied with the…’ he snapped his mouth shut and looked suddenly sober. ‘Of course. You think I’m some kind of nut.’

‘It’s not that…’

He stood up, fiddled through his wallet and stacked the cost of the gin on the table in coins.

‘It was on me,’ she said.

He walked out of the pub. After a moment of feeling frustrated at herself, she left the coins and jogged after him, but he was nowhere to be seen in the hot street. White gulls pecked at the remains of fish and chips, gobbling batter and polystyrene tray alike. For a moment she thought the whitest of them had white eyes, but it was only a trick of the light.

5

From an aeroplane the three main islands of the St Hauda’s Land archipelago looked like the swatted corpse of a blob-eyed insect. The thorax was Gurm Island, all marshland and wooded hills. The neck was a natural aqueduct with weathered arches through which the sea flushed, leading to the eye. That was the towering but drowsy hill of Lomdendol Tor on Lomdendol Island, which (local supposition had it) first squirted St Hauda’s Land into being. The legs were six spurs of rock extending from the south-west coast of Gurm Island, trapping the sea in sandy coves between them. The wings were a wind-torn flotilla of uninhabited granite islets in the north. The tail’s sting was the sickle-shaped Ferry Island in the east, the quaint little town of Glamsgallow a drop of poison welling on its tip.

Glamsgallow boasted St Hauda’s Land’s only airport, but most aeroplanes crossed the islands before turning to land, flying over the other settlements. In the north of Gurm, walled off to the public, was Enghem, the private property of Hector Stallows, the local millionaire. Built at the foot of Lomdendol Tor, Martyr’s Pitfall was a town for the elderly. On Sunday afternoons the shadow of the tor covered the buildings and streets. Couples trickled from retirement homes to walk and sit in landscaped graveyards. By contrast, Gurmton attracted the young and nocturnal. Thousands of lights twinkled on its seafront, from the frantic flashes of fruit machines and jukeboxes to the spotlights slicing the sky at night, beaming the rival logos of two sleazy nightclubs on to the clouds.

Behind Gurmton the woods began suddenly. Lost partygoers looking for the seafront sobered up in seconds when they stumbled upon the eaves of the forest at night. Likewise, people driving the shadowy roads inland through the trees became aware of the din of their engines. Stereos would be turned off and conversations postponed. The woods felt like a sleeping monster worth tiptoeing past.