9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

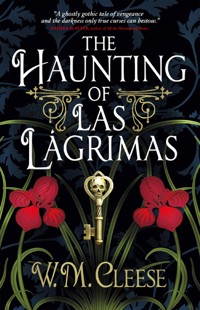

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

An atmospheric Gothic ghost story, where The Silent Companions meets Daphne du Maurier in South America and a woman faces the darkness bestowed by vengeance. "A phantasmagoric mixture of M. R. James, The Shining and The Turn of the Screw set among the otherworldly Argentinian Pampas." - EDWARD PARNELL, author of Ghostland Winter 1913. Ursula Kelp, a young English gardener, has come to Argentina to restore the gardens of Las Lágrimas. The long-abandoned estate lies deep in the Pampas, the vast empty grasslands of South America where the wind blows without end. Despite warnings from the locals of terrible things that once happened there and the evil that lingers, Ursula sets out to her new post full of hope. Yet when she arrives, all is not as promised. The garden is an untameable wilderness, the staff hostile. Setting to work, Ursula is disturbed by the crunch of footsteps on empty gravel paths, while from the nearby forest comes the frenzied chop of an axe when no one is there. But it is only as she unlocks the secrets of the place that Ursula comes to understand the true horror she is facing. For lurking in the trees – watching her, waiting for her – is a malevolent force that wants Las Lágrimas for itself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 515

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Note on the Text

The Hotel Bristol, Mar del Plata

A Stranger in the Garden

The House of Tears

Maldita (adj.)

Rivacoba Makes Arrangements

Across the Pampas

Dinner for One

A Tour of the Garden

The Trophy Room

The View from the Treehouse

A Most Violent Sound

The First Bath

Beneath the Veil of Thorns

The Axeman

The Melancholia of Sr Moyano

Inside the Cabin

The Cold in my Bones

Dry Matter

A Morning at Leisure

The Quarry & the Boy

From Behind the Door

Calista’s Remedy, Calista Speaks

Gift or Warning?

Treasures . . . & a Surprise

Berganza’s Tale

The Lights in the Trees

Words with Latigez

Over the Wailing Wall

Giving Notice

Calista is Offended

Never an English Rose

Mantrap

Old Metal & Honeycomb

‘Wrist to Elbow’

The Arrival of Don Paquito

Blood on my Clothes

The Garden & the Ghost

Take Me with You!

A House in Mourning

Not Quite Alone

Amidst the Amaranth & Moly

A Fair Plan

Hideously Afraid

Beneath the Ombú Trees

Once More into the House

The Endless Way Ahead

Postscript

Hearsay & Speculation

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

or your preferred retailer.

The Haunting of Las Lágrimas

Print edition ISBN: 9781789098334

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098341

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition February 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2022 W.M. Cleese. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Nicole

Note on the Text

The following narrative was written in October 1913 in the journal of Ursula McKinder (née Kelp). Now a forgotten figure, in the decade after the war Ursula was a widely respected gardener counting the likes of Sir Arthur William Hill, the director of Kew Gardens, among her circle.

Although the original journal has since been lost, while researching my book on the Malayan Emergency, I discovered a photostat of it in the papers of Ursula’s daughter, Flores. This reproduction was most likely made in the 1950s in Singapore, where the family had relocated to avoid the bloodshed in Malay. Quite why Flores made a copy remains uncertain.

In preparing the journal for publication I was able to verify many elements of it: Ursula’s passage to Argentina aboard the RMS Arlanza; her employment in Buenos Aires with the Houghton family and sudden resignation; her subsequent stay at the Hotel Bristol in Mar del Plata. I even uncovered a receipt for the latter, her accommodation coming to 336 pesos (settled by banker’s draft). It is also evident that Ursula had travelled in the Pampas region. The contents of her grandfather’s will wereconfirmed by records held in the Cambridge offices of Cole, Cranley & White, solicitors.

As for the disturbing events described at Las Lágrimas between 17 August and the first weeks of September 1913, I leave the reader to judge.

WMC, February 2022

SATURDAY, 4TH OCTOBER 1913

The Hotel Bristol, Mar del Plata

EVERY NIGHT THE same thing happens.

I take supper in the hotel, insisting on a table in the centre of the restaurant, beneath the main chandelier, so that I am bathed in glittering light and surrounded by as many people as possible. Never did the hum of idle chatter reassure as much. I sit with my back to the windows to avoid the inky blackness of the ocean beyond. I eat only the day’s catch or salad, to rest easily on my digestion, and finish with a generous glass of port wine – not to fortify but to drug me.

Then to my room where I draw a bath. The water is fiercely hot here and afterward I am left broiled and drowsy. I put on my nightclothes and sink into the sheets. They are so soft, especially with the memory of sleeping in the wilds of the Pampas still fresh in my mind. Out there, in those vast empty grasslands, the ground was hard and sodden; I had nothing but a poncho to protect me from the howling cold as I huddled, hungry and alone, in the grip of fear. Every light in the bedroom I keep switched on, something I would have once found a nonsense. Now I tremble at shadows – and what they may conceal. Finally, I swallow a sedative and close my eyes.

At first it feels as if tonight I shall be successful. My limbs relax, my breathing deepens. I slide into my private darkness and begin to drift, dimly aware of the sounds outside the window… The crash and hiss of waves against the beach, the whip of the wind through palm trees…

Then all at once I am at Las Lágrimas again – and I awaken. Thrashing and gasping and begging for deliverance.

The remembrance of that dreadful place has been with me all day: when I rise from another sleepless night, when blearily I eat breakfast, when I stroll through town. Stroll? I march, practically at a dash, around Mar del Plata, racing along the rambla to where the coastline is undeveloped, then up to the cliffs before winding back my path through grids of pretty, Alpine-fashion houses to the seafront. There have been occasions when twice I have followed this circuit. The locals are beginning to recognize me: the demented inglesa with her darkly ringed eyes and trailing red hair. I walk a dozen hours of the day in the vain hope I will exhaust myself sufficiently for bedtime.

I must admit that in the daylight and bracing sea air, with an abundance of people around me, I am something of my old self – albeit the numerous pleasure gardens I pass with their thoughtful planting patterns and eye-catching symmetries, gardens just now coming into bloom, gardens where once I could have idled away many happy hours, no longer captivate my interest.

Mar del Plata is a modern seaside resort growing, as high-season approaches, more clement and populated by the day. Electric-lights illuminate the streets. My hotel, the Bristol, is the best in town, plush and secure behind lock and door aplenty. Rationally, I am assured that no harm can come to me here. Yet when the memory of Las Lágrimas forces itself upon me, the terror of recent events is as immediate and blood-chilling as it was during those last days at the house. My heart hammers with such fierceness that I know I shall be awake again to witness the dawn. It has been no different these past two weeks. I came to Mar del Plata to exorcise these memories, not fall deeper under their spell.

I must do something!

On previous nights I have paced my room in a fever of agitation before, inevitably, I take myself downstairs, craving the society of others. I frequent the lobby until the small hours when all the other guests have retired and my only company is the night staff. The concierge must think I am sweet on him or, I daresay, deranged. As a young Englishwoman staying here with neither family nor husband nor any chaperone, I have raised eyebrows enough already.

I wish Grandfather were with me; never have I missed him so much. I do not need his presence, however, to be confident of what he would advise. His study was lined with the journals he had kept: leather-bound logbooks that had seen half the world, their pages distended with the salt of sea voyages and the steam of jungles more distant than ever I could imagine. Every hardship he suffered, every tropical fever and mortal threat – all those adventures that thrilled me as a child – laid to rest by writing them down. ‘Ink on paper,’ he would say, ‘soothes the soul.’

I hear his voice now: Write, Ursula! Write it all down, in every last detail, and it will trouble you no further.

Can it possibly be that simple?

When I fled the house at Las Lágrimas I took only the barest of essentials. The rest – my clothes, books, gardening tools, nearly all the worldly possessions I had brought with me from Britain to Argentina – I had to abandon. I try not to think whether unseen fingers have since picked through my belongings. One thing I did slip into my pocket before I took flight was my fountain-pen, a gift from Grandfather for my twenty-first birthday, that I refused to leave. There is a stationer in the arcade by the hotel. Late this afternoon, as I returned from my long walk, I went in on the spur of the moment and purchased a pot of ink and a stiff-backed notebook bound in cloth, the self-same book I am writing these words in. I do not want to spend another night lingering in the lobby or shivering in my room purblinded by an excess of lights. I do not want a future where the thought of bed brings nothing but trepidation. I have never been prone to the nervous conditions that afflict many of my sex, like my sisters; damn it! say I, if I will start now. I have always understood that I am different, my temperament stronger. Indeed, I feel more possessed of myself simply in the knowledge of what I am about to undertake. I must summon all my bravery again, as I did on that final night in Las Lágrimas.

And so I shall describe the happenings of these past weeks, setting them down as Grandfather would urge me to: in impeccable detail, as relentlessly truthful as if I were standing in court – though I am not sure all will make sense. Where the specifics are lost to me (I think, in particular, of the many ephemeral conversations) I shall capture their essence if not exactitude. I state this plainly, in advance, in order that the reader be confident that what follows is as accurate and faithful account as possible. When I am done, I pray I shall find peace anew. That it will be granted to me to lie on my crumpled bed, turn out the light-switches, and sleep. Dreamless, uninvaded sleep.

This, then, is the story I must tell. I must take myself back to Las Lágrimas. God preserve me, I must live it all once more.

A Stranger in the Garden

IT WAS THE twelfth day of August, on a dismal, chilly morning – late-winter in the southern hemisphere – when the stranger returned. Although the hour was early I was already at work in the garden, my woollen overcoat damp from the air, the tips of my fingers red and numb. To be clear, the garden was not mine. It belonged to the Houghtons, associates of my solicitor, who had lived in Buenos Aires a decade since. Their house was one of the many mansions in the Belgrano district of the city, a grand property obscured by high brick walls and mature trees, they being a rather impressive collection of jacarandas, la tipas and Japanese maples, all leafless at that time of year.

I recognized the stranger at once not least from his height. He was tall (especially for an Argentine), with a gaunt but gentlemanly face, and wearing a pigskin coat that hung down to his boots. On his head was a bowler hat. He had visited several days before and spoken with Señor Gil, our Head Gardener. It had been a brief exchange and Gil had sent the stranger packing with his usual charm. We were a garden staff of four, with myself as the most recent addition, and there was much speculation as to who this visitor might be. Gil had taken great pleasure in being tight-lipped on the subject, implying the stranger heralded important news, but offering no further insight.

The previous encounter between the two had been by appointment in Gil’s hut, a building he insisted we refer to as his ‘office’. That morning, however, the stranger had let himself into the garden and ambushed Gil near the iris and lupin borders. By chance I was passing nearby, my hands cupped together holding a mouse’s nest. Gil often gave me jobs that brought me into contact with insects and rodents. His hope was that I would scream like an infant, but Grandfather had taught me to fear nothing, certainly not creatures smaller than my thumb! I had been clearing out pots when I found the mouse. Gil had a custom of stamping on the poor mites, so I wanted to move her to a corner of the garden where she might live unmolested. I was thus bound when I caught Gil and the stranger in conference. I was not popular amongst the staff. Any snippet of gossip I might come by would improve my standing, so I concealed myself and listened. I must confess to a certain thrill at eavesdropping, one of my uglier habits, and something Mother had often chided me for.

Gil had a spectrum of tones from the blatantly obsequious when he spoke to the Houghtons to his toad-voice for those beneath him. Presently, his parlance was at its most amphibian. ‘… as I told you last time, I have no interest in your offer. Now leave. I’ve a busy morning.’

‘Imagine the opportunity,’ was the stranger’s reply. He had an odd voice, commanding with a hint of the cocksure, yet a fragile quality also. ‘Not a garden but an estancia. An entire estate for you to oversee.’

‘Even if it weren’t for the rest of it, who would want to live out there?’

‘With the new rail-line to Tandil, you can make the journey in two days.’

‘I don’t care for trains.’

‘Perhaps it’s the salary?’

‘Nor do I care for your money.’

My ears pricked up. Here was a detail that would startle the others when shared. Few men were more avaricious than Eduardo Gil.

‘My employer is prepared to double his offer,’ said the stranger.

‘I have nothing else to say. I do not want your job, and I doubt you’ll find any man willing to take it.’

I slipped away, my mind racing. Here was an opportunity to prove what I was capable of, to work as a proper gardener rather than a pair of ‘extra hands’ tolerated only because of my connection to Mr Houghton.

I hurried to the wall that bounded Calle Miñones, lowered the mouse and watched her scurry off. ‘Good luck,’ I wished us both. Then I straightened my overcoat and arranged my hair more tidily beneath my hat. I could never be troubled to do much with it, another misdemeanour that earned me a daily rebuke from Gil. The Houghtons’ garden was designed along a grid of paths and hedges (it was, to my tastes, a little too formal). I skipped through them, positioning myself at an intersection where I knew the stranger must pass on his exit, and waited for him, pinching my cheeks to bring some colour to them. I breathed in damp lungfuls of air to steady my excitement – there was a smell of turned earth and leaf mould – and prepared what I would say. As the crunch of his footsteps on the gravel approached, I stepped out, moving deliberately so as not to waylay him. His face was a picture of annoyance and dejection.

‘Señor,’ I said, ‘my name is Ursula Kelp. I overheard your conversation with Gil and understand you are looking to employ a gardener.’

‘A Head Gardener, at an estancia in the Pampas, where I am the manager. Do you know of someone favourable?’

‘I myself would like to apply for the position.’

He fixed me with his eyes and I feared he would laugh – but for a long while he said nothing. There was a hint of violet to his irises; the slightest bend to his nose. I did not shirk his gaze, Grandfather would expect nothing less, though as the seconds ticked past I had to tuck a strand of hair behind my ear by way of maintaining my composure. The stranger did not relent, as if challenging me to look away, as if he were a soul-reader. Now, of course, I wish I had – but at that moment, I had not the least intuition of the consequences.

Finally, and in a grave tone, he said, ‘It is no job for a woman.’

‘I have gardened all my life,’ I answered him, bristling, ‘and am versed in horticulture as well as any man.’

‘Where are you from, Señorita? Your Spanish is good but you’re no Argentine. Nor is your complexion.’

‘From Britain.’

‘English?’

He seemed rather emphatic on the point, which I thought a tad queer. I replied yes, from the good county of Cambridgeshire, adding, ‘I can provide letters of reference should you require.’

His eyes were still set on mine, his whole bearing inanimate except for a scratching of his wrist as if some irritation troubled him there. I sensed a struggle – a calculation – going on behind his stare. ‘Would you have the kindness to show me your hands?’

I have always found my hands a little on the inelegant side, not unattractive, you understand, but better buried in the soil than resting idly on my lap, manicured and adorned like my sisters’. I hesitated, then presented them, unsure what he was looking for, concerned they were either too clean or too grubby for his intended purpose.

‘Do you mind?’ he asked and, before I could reply, he had seized my hands, rubbing the skin to test how calloused it was. He rolled them over so my palms were facing downward and assessed the knuckles. For an alarming instant, I was convinced he planned to raise my fingers to his nose and sniff them. There was something rough in his manner as though he were examining the fetlocks of a nag at market. I freed myself from his grasp.

When next he spoke his voice was not unkind. ‘Do you know Café Tortoni’s?’

‘Of course,’ I replied.

‘Meet me there this Thursday evening, six o’clock sharp. If I haven’t found someone to fill the position, you might be in luck.’

‘My hours here are until six.’

‘Then you will be late and I will be gone.’

With that he tipped his bowler, and strode away.

The House of Tears

FOR THE NEXT two days I could do nothing but speculate about this post. Working in the garden – digging, winter-pruning the salix and buddleia, scalding pots – my thoughts roved endlessly to it.

I had been at the Belgrano garden for six months already; I doubted I could suffer many more. The work itself was unfulfilling and made little use of my talents, and though I had discreetly looked for an alternative position, none was to be found. I was painfully lonely and found no respite in the staff that to a man – and in the garden they were all men – treated me with suspicion: because I was British; because I lived in a room in the main house, not the gardeners’ block or attic; because Mrs Houghton treated me more as an equal than an employee. I am sure they thought me as a spy set amidst them. The Houghtons themselves were decent enough if not ‘our kind of people’, as Grandfather would say, being too interested in the price of everything and the value of nothing. Bernadice, the eldest daughter, was forever harping on over whether I had a beau back home and when I was going to get engaged; the word ‘Suffrage’, let alone the concept, was as profane to her as it was to my sisters. Even the garden was an object of mere show: an ornament to demonstrate their wealth, they having no true appreciation of the flowers, shrubs and trees per se. ‘How can you know so much about plants?’ Mrs Houghton would exclaim to me in marvel and what I thought was slight rebuke, the same rebuke I knew too well from my parents who had only ire at my wanting to garden as a profession. The one advantage of the Houghtons was they were often out of town.

If Grandfather were still alive, I would have written to him every week, unpacking my heart, and found solace in those letters. Instead, once a month I sent a brief epistle to my family, full of fallacies of how wonderful I was finding Argentina. I received no replies. To work on an estancia, where the gardens must surely be as expansive as they were grand, and achieve such through my own merits was as a dream come true. To be candid, the position of ‘Head Gardener’ also appealed to the vainer side of my character.

* * *

Thursday afternoon arrived. I could have asked Gil to finish early or gone to him feigning some womanly complaint but I feared he might thwart my plans. He rarely passed on an opportunity for vindictiveness toward me, especially given the Houghtons were away at the time. In the end, I simply took myself from the garden when no one was about, returned to my room, washed, changed my outfit and left bold as anything through the front door.

Dusk was already settling upon the city, the sky mauve and misty, the streetlamps fuzzing orbs. As I headed to the tram-stop the air chilled my throat. Many things had astounded me about Buenos Aires, not least how wealthy, modern and Europeanized it was. More unanticipated, however, was the weather. It had been hot and fine when first I landed but, as the year turned, the city was gripped by days of low, murky clouds. Fogs were not an irregular occurrence. These had nothing on a London particular, but were sufficient to veil the streets and cast one down. The Argentine capital certainly fell short of its name, Buenos Aires: good airs. I took the Number 35 tram to Avenida de Mayo and walked the final blocks through swirling vapour. It was a relief to reach the lights of Tortoni’s.

Inside, chandeliers reflected off mahogany walls and smoked-glass panels, giving everything a welcoming, amber-coloured glow. It was crowded, and I felt immediately enlivened by so many people and their convivial chatter, not to mention the sweet, buttery aroma of the patisserie. The café had a reputation for the best cake, coffee and chocolate in the city – and the most condescending staff. The maître d’hôtel sniffed as I approached him.

‘We are most busy, Señorita. You will have to wait.’

‘I am meeting someone. A gentleman acquaintance. He said he would have us a table.’

‘His name?’

I went to reply and it occurred to me that I had been so keyed-up by the prospect of a Head Gardenership that I had never enquired of the stranger’s name nor the estancia he represented. I foundered, at a loss as how to respond. The maître d’ made no attempt to conceal his irritation and was about to offer some reprimand when there was a touch on my shoulder.

‘Buenas tardes, Señorita Kelp.’

The stranger had already taken a table and, upon seeing my entrance, emerged from the depths of the café to rescue me. His countenance was still gaunt but his face was more handsome than I remembered, a rather long, Spanish face, and very smoothly shaven. I studied it until he caught me, and quickly averted my eyes. He had thick hair of the darkest hue, swept back off a high forehead.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, regaining my composure. ‘I forgot to ask your name.’

‘Juan-Pérez Moyano.’

I offered him my hand. ‘Pleased to make your acquaintance, Señor Moyano.’

He chuckled at my formality and we shook. His skin felt curiously soft to mine, as though slathering his palms in ointment was for him a daily ritual. He guided me away from the maître d’ and in the direction of his table. ‘Have you come from a funeral?’ he asked with a hint of mischief.

I had worn a black, unembroidered dress and hat with no jewellery, my intention to look as serious-minded as possible. All the other women in the café were gaily attired, as bright and colourful as zinnias, and I admit to a prickle of embarrassment – one I was determined not to show. ‘You should not joke about such things,’ I replied tartly. I sat down before he had the chance to pull back the chair for me.

Without enquiring as to what I would prefer, he signalled a waiter and ordered two hot chocolates. Whilst we waited for them, he began some small talk, but I wanted to know whether I had made a wasted trip or not.

‘Did you find a gardener?’ I asked.

‘There was interest.’

‘But my being offered the position is still a possibility?’

‘A possibility. Yes.’

‘Then you must look at these.’

I handed him my references. Moyano took them from their envelopes and read carefully before his face creased into a frown. ‘These are encouraging, Señorita, but who, may I ask, is this “Deborah” Kelp?’

‘Deborah was the name I grew up with. Now I prefer Ursula. It’s what my grandfather called me.’

‘And why did he do that?’

‘Señor Moyano, are we here to discuss my name or my suitability for employment?’

He returned my references and looked at me deeply. ‘Have you heard of the Estancia Las Lágrimas?’

‘Should I have?’

‘It was once the grandest house in all the Pampas. An estate of more than seven thousand hectares. It is where I am the general manager.’

‘It doesn’t sound very jolly.’ Las Lágrimas, Spanish for ‘the House of Tears’.

Moyano allowed me a tolerant, little smile. ‘It’s said that when the founder first laid eyes on that part of the Pampas he was moved to weeping by the beauty of the place. Once the house was built, people would visit from all over. It was famous for its parties, for its hunts and Christmas balls. And not least its garden. Then the owner decided to leave.’

‘May I ask why?’

The waiter arrived with our order. I took a sip of chocolate. It was deliciously thick, but after a second mouthful tasted overpowering. I had not eaten since lunch, and by the time I drained the cup I experienced a certain queasiness.

‘He took to God,’ was Moyano’s reply. ‘And devoted the rest of his life to prayer. For thirty years the estancia has lain empty. Now my employer – Don Paquito Agramonte, son of the last owner, grandson of the founder – has inherited the property. He wants to return it to its former glory and live there with his family. He is keen to restore the garden to the one he remembers as a child.’

‘How is it now?’

‘As any garden that’s been abandoned for so long: something of a wilderness. It will need work! The garden was planted in the English-style, which is why you might be an ideal candidate.’

‘Are you offering me the post?’

‘If I were, you do understand the remoteness of the Pampas? There are no nearby towns, nor even other houses. There are few of the modern conveniences, no telephone, only part of the property has electricity. You can get mail, but one never knows when it arrives.’

‘I should be glad for the opportunity.’

He spoke his next words with feeling, almost as if hoping to dissuade me. ‘I fear it might demand too much for the female constitution. It gets very lonely.’

I gave a dismissive snort and, thinking of my life at the Houghtons, replied, ‘I have a tolerance for it, Señor.’

‘You would have a team of gardeners working beneath you, men who may not like taking orders from a woman. They will be labourers, not horticulturists.’

‘So you are offering me the job?’

He leant forward, not quite touching my leg beneath the table but close enough that I was aware of the movement against my dress. ‘There’s one thing I’m curious about, Señorita. How did you come to be in my country?’

I took care in answering for it was a matter I had no desire to discuss. ‘Because of my grandfather.’

‘He’s with you? He will not be able to accompany you to the estancia.’

‘He died. Last year.’

‘Ah. I am sorry to hear that, Señorita.’

‘His wish was that I make gardening my profession.’

‘Surely you could have found somewhere closer to home.’

‘I wanted to improve my Spanish.’

‘There must be more to it than that.’

‘To be entirely honest,’ I replied by way of distraction, ‘I was fed up with the British. We’re everywhere: Africa, Asia, the Antipodes. As a nation we are drawn to exotic places; it’s stifling. So to Argentina I came. Little did I know.’

Along with my dismay at the weather, another revelation had been the sheer number of British, working in the meat industry or building the railways. We even had our own daily newspaper, the Buenos Aires Herald. I should have foreseen it by the fact that people like the Houghtons lived here; they were beef money.

Moyano found my explanation amusing. ‘Well, Señorita, you’ll certainly find none of your countrymen in the Pampas.’

‘Then it would seem I am a perfect match.’

‘In which case it is my turn to be honest with you. I have asked every gardener in Buenos Aires to take the position at Las Lágrimas. I even took the ferry across to Montevideo to find a man there. Everyone refused me. Which is why the job is yours, should you so like it.’

It was not the most auspicious of starts, but barely twenty minutes after arriving at Tortoni’s I found my signature on a contract of employment and my person outside on the pavement, lost in the fog again. If I could have overlooked my excitement, or the relish with which I would communicate to my family this promotion, I may have had pause to ask why such a prestigious job had been offered to me with such ease. Or, more importantly, why every other candidate had thought better to reject it.

Maldita (adj.)

IT WAS IN an altogether more aggrieved mood that I reached Constitución station the next morning. I was travelling with every item that had made its way with me to Argentina, namely three suitcases of clothes, two hatboxes, a vanity case, a chest of gardening implements and Grandfather’s trunk, heavy with books and sundries. The station was cavernous and gleaming (the latest extension had been completed the year before), and reminded me of St Pancras in London. It was filled with a sense of bustle and languid, Latin urgency, the air sweetened with smuts. I found my platform, number 5, supervised the loading of my luggage, then took my seat. Señor Moyano, courtesy of Don Paquito, had provided for a first-class carriage. I settled down and waited to leave, still fuming at what had transpired earlier that day.

Moyano expected me to start forthwith at Las Lágrimas. Don Paquito and his family planned to take up residence in September. A firm of builders had been renovating the house but the garden remained ‘a wild beast’, as Moyano described it. He wanted a semblance of respectability to the exterior before the Don arrived. We agreed I would take the Friday morning train to arrive at the estancia by Saturday and start work on Monday, 18th August. After leaving Café Tortoni’s, I returned to Belgrano and, with scarcely concealed triumph, went to see Gil in his hut. A meagre fire was burning in the stove. He told me to take a seat; I refused him.

‘I wish to hand in my notice,’ I declared.

‘To leave when?’

‘Immediately.’

Gil let out a long, condescending sigh. ‘Your contract stipulates a month’s forewarning, Señorita.’

Whilst Mr Houghton felt it unnecessary for me to sign a contract, Gil had been adamant, saying that exceptions could not be made otherwise it would foster resentments amongst the staff.

I decided to make plain my mind. ‘Señor Gil, please, it is winter, the garden far from busy. I am sure no one, least of all you, will mourn my departure. Why not simply release me?’

‘A contract is a contract, Señorita Kelp.’

‘You can be reasonable, Señor, or I can speak with the master of the household.’

‘You could. But you know, as well do I, that the family is away for another week. I thought you wanted to leave at once.’

‘I do.’

‘Have you found a new position? Or are you returning to a life of idleness?’

‘You can’t refuse me.’

He sucked on his teeth, a habit I found disgusting. ‘Your departure wouldn’t have anything to do with Moyano sniffing roundabout?’

I felt a rush of loyalty to my new employer, equally I wanted to give away nothing. ‘Who?’

Gil was not taken in by my subterfuge. This time he chuckled to himself. ‘That wastrel asked every gardener from here to Uruguay to take the job. Not a single man wanted it. If you understood anything of my country, Señorita, you would be of the same mind.’ Gil pondered the matter. ‘If you’re heading to Las Lágrimas, your notice is duly received. Good night.’

I cannot say I was sad to leave the Houghtons, for they had always reminded me too much of my own family for comfort. All the same, the next morning I left a note of farewell and genuine thanks, then went to see Gil for the final time to hand back my door-key and collect my wages for the month past. None were forthcoming.

‘You are in breach of your contract,’ he said, waving the agreement in my face.

‘But the work I did!’

‘A consideration you should have made before swanning off to the Pampas.’

Such was my zeal to start afresh, I had rather overlooked this complication, and though Gil may have been strictly correct, I nevertheless felt the hand of unfairness. ‘I shall speak to Mr Houghton about this.’

‘And he’ll show you the exact same clause. “Should an employee leave without due notice, those earnings outstanding will be forfeit”.’

Waiting for my train to depart I fought back hot, rising tears. It was not the money, you understand, it was the principle of the matter, one that summoned memories I had tried my utmost to bury, for I felt anew the injustice of being denied what was rightfully mine through the malice of others. For several moments I was transported to the office of a Cambridge solicitor as Grandfather’s will was read, my heart racing violently, until at last I made every effort to calm myself for I had no wish to make a show in public.

As it happened, only two other passengers joined me in my compartment. The first was a man of the type my sisters would describe as ‘eligible’. He gave a polite nod before applying himself to his newspaper and, thankfully, paid me no heed for the rest of the journey. Shortly after, a woman of Mother’s age entered. She was well outfitted with rough, veiny hands that wore fine diamonds. By her side was a cat-basket, though I saw no feline face.

At a quarter to ten, the guard blew his whistle and we began to chug away. The mistiness of the past few days had vanished overnight, the sky being a hydrangea-blue, the sun watery yet bright. The train passed through the centre of Buenos Aires, then less salubrious districts where shacks huddled either side of the line and the air had an intense, gamey tang; the skyline was dominated by the chimneys of meat-processing factories. Soon after, urban landscape surrendered to the grasslands that mark the city’s limit. This was the first fringe of the Pampas. Of the region I knew little other than its vastness. It stretched from the Atlantic in the east to the foothills of the Andes in the west. The Rio Negro, the boundary between the Pampas and the land of Patagonia, was a thousand miles to the south. And in between nothing but flat, empty plains and the occasional estancia. On my map of Argentina it was drawn as a green enigma, marked with few towns and no features. The railway had braved this territory only in the last five years.

Gazing out of the window, the sun flashing into my eyes, I forgot Gil and those other, hurtful memories and instead experienced a stirring of adventure. It was not by coincidence I had come to South America: as a young man, Grandfather had travelled the continent, and to be here myself offered the solace of some connection to him, however tenuous. Perhaps, some day in the future, I would follow the route he had taken and experience in person those wonders he had related to me.

Many hours lay ahead to my station. Although the grasslands may have held the promise of adventure, after a time they did become rather monotonous. I took out my novel, Nostromo by Joseph Conrad (a favourite of Grandfather’s, which I was dutifully ploughing through), and read. At the town of Vilela, the man opposite folded up his newspaper and disembarked. No new passenger joined the carriage. At Las Flores, I had to change trains for the branch-line to Tandil. By now it was lunchtime, and I bought some empanadas to eat whilst I waited for the connecting service. My train arrived late, and I again found myself a companion of the woman I had travelled with from Buenos Aires, the one with the cat-box. We passed a few pleasantries during which she introduced herself as Doña Ybarra. Once the train had left the station, I returned to the Conrad before feeling tired. I closed my book and napped until, some indeterminate period after, I was woken by a jolt.

The train had come to a standstill, not at a station but on a siding in the middle of nowhere. A sea of grass, rippling and swaying in the breeze, stretched as far as the eye could see out of both windows.

‘Do not be troubled,’ said Doña Ybarra, observing my concern. ‘Delays are what we live with in the Pampas.’

‘I’m meeting someone,’ I replied, ‘and afterward have a long journey ahead. I do not want to be late.’

‘If they know the trains, they will know to wait.’

Whereupon we sat in silence except for the steady wheeze of the locomotive. The minutes passed and became a quarter, then half of an hour. I picked up Nostromo, but after a few pages realized I had taken in nothing of what I had read. Outside, the day began a slow but perceptible fading.

I stood up, rapping my knuckles against the window. ‘How I hate dawdling,’ I let forth in English. Doña Ybarra started at this outburst in a language alien to her. I apologized and translated my words.

‘We’ll be on our way soon,’ she soothed. She was feeding her animal, dangling morsels of meat through an opening in the basket’s top. ‘It is only a single track ahead. Most likely we’re being held for the up-train to Las Flores.’

‘I hope so,’ I replied, peering into her basket. I expected to see a wide-eyed, whiskered countenance. Instead, a lizard blankly returned my gaze.

‘My iguana,’ explained the woman.

What does one say in reply to a reptile? ‘I’m sure they make loving pets.’

As if to confirm my statement she removed the beast, her rings flashing, and held it to her cheek, making a cooing sound. ‘Where are you from, Señorita?’ she asked, replacing the creature in its basket.

‘Britain.’

‘Your Spanish is excellent.’

‘My grandfather taught me. He had travelled across all the Americas.’

‘And what brings you to these parts?’

‘I have been offered a position, at an estancia.’

‘Let me see,’ she replied, animated by the prospect of a guessing-game. ‘A housekeeper?’

I shook my head.

‘Of course not. You are far too educated. Governess?’

‘Head Gardener,’ I answered, liking how it sounded for in those two words were encapsulated all my ambition and love of horticulture.

Doña Ybarra puckered her lips. ‘A rather unusual choice for a lady. Which estancia?’

‘Las Lágrimas.’

Her expression became more complex, her disapproval combining with dismay. ‘Why would you want to go to that place? It has been deserted for years.’

‘You know of it?’

‘My husband and I, when we were young and recently married, were often invited there. Such lavish parties! The food and drink, the dancing through the night.’ She recollected this without a flicker of enthusiasm. ‘But I never liked Don Guido, the owner. You couldn’t refuse his invitation, yet I never knew one more godless.’

It was a description that seemed not to tally with Moyano’s. ‘We are talking of the Agramonte family?’ I asked.

‘Guido Agramonte, yes. A wild, profane and godless man.’

‘His son, Don Paquito, has taken possession of the estate, and wishes to restore it.’

‘Then he is either very brave. Or a fool.’

‘Why do you say these things?’

‘Has no one told you about Las Lágrimas?’

‘It would appear not.’

‘The estancia is notorious in these parts.’ She phrased her next words with care. ‘It is maldita.’

As already noted, my Spanish is most proficient – albeit I am not wholly fluent. I still come across words I am unfamiliar with and, to that end, always keep my Tauchnitz* at hand. I flicked through the pages until I found maldita. It was an adjective, meaning ‘cursed’, and not the kind of poorly informed, heathen belief I would expect in a country as modern as Argentina. ‘Doña Ybarra, you will forgive me, but my grandfather, when travelling in Peru, was put under a curse, yet little ill-fortune ever befell him. He was healthy and happy to the end, and passed away peacefully in his own bed.’

‘Do not think me some superstitious old woman, Señorita. The curse of Las Lágrimas is as real as this carriage. As real as you or me. Why do you think no one has dared live there for decades? You would be unwise to take it lightly. They say the dead walk the grounds of the estate.’

I was at a loss how to reply, being, at best, agnostic on such matters. I thought back to Grandfather’s final day. He had died in the spring, gently squeezing my hand as I sat by his bedside. The scent of quince blossom floated in through the casement. And though I may have feared for myself and what the future might bring, from that dear, old man I felt a great peace as his grip weakened and he left me. In my naïvety, I could not imagine why the dead would wish to return.

At that moment, there was a whistle-shriek and, on the main track, a train trundled by: window after window of intermittent faces and vacant seats. As soon as it had passed, our own carriage jerked forward. ‘We’re on the move again,’ I observed, bringing our conversation to a close. I picked up my novel and made an emphatic show of reading.

We did not exchange another word until we reached Miranda, the stop before mine. As Doña Ybarra gathered up her lizard, I bade a cheery farewell. She replied in kind and was on the point of leaving the compartment when she grasped me.

‘I know you think me a dolt – but please reconsider, Señorita. Do not go to Las Lágrimas. Take the train back to Buenos Aires. Go back home to England.’

* The most commonly used English–Spanish dictionary of the day. I found a well-thumbed pocket edition in the same box as the photostat of Ursula’s journal, along with various other items (letters, photos, bills, etc.) from her time in South America.

Rivacoba Makes Arrangements

THE SUN WAS beginning to set by the time the train pulled into Chapaledfú station, the sky streaked with magnolia-pink cloud. The platform was deserted and unwelcoming. Moyano, who had returned to the Pampas the same night as our interview, promised someone would be waiting for me.

‘How will I recognize him?’ I had asked.

‘I think rather, Señorita, he will recognize you.’

As I struggled to unload my luggage, I heard a baritone voice behind me. ‘Señorita Kelp, from England?’

I turned to face a gaucho of singular appearance, robust, unshaven and dressed in traditional costume: bolero hat, a damson-coloured poncho, pantaloons beneath fur chaparejos and boots of colt-hide; his spurs were fearsome. Later, I learnt that he was more than a simple gaucho, rather he was a baqueano, the name by which the guides of the Pampas call themselves, men whose endurance and topographical knowledge of the region is formidable. ‘I am Rivacoba,’ he growled. ‘You are late.’

It was not quite the greeting I had imagined, and I found myself replying in kind: ‘Blame the Southern Railway Company, not me.’

‘We cannot leave tonight.’

‘Surely we can start out?’

‘Look at the sun. Within the hour it will be blacker than pitch. What would be the point? I have made arrangements.’

Chapaledfú was an inconsequential farming town. If the purpose of the railway line was to advance the modern world it had so far fallen short; indeed my experience of the place was of travelling backward in time to the middle of the previous century. The town consisted of a flagstoned plaza from which led a few unpaved roads, some houses (a dozen or so of brick, the rest in timber), two or three shops, an abattoir and a smattering of agricultural buildings. There was no hotel. Instead, Rivacoba’s ‘arrangements’ meant boarding with the station-master and his wife. They had a little cottage that adjoined the railway platform, cramped but cosy enough. To my shame, the station-master’s blind mother was ejected from her room so I could sleep there. There was no sign of children. Before Rivacoba left me for the night, to lodge who knows where, he informed me of another misdemeanour: ‘You have too many things.’ I was handed a pair of panniers and a small trunk. ‘Pack what you need in these.’ I insisted that, actually, I needed everything I had brought, but was met with a gruff, unyielding response.

So it was that I spent the first hour of my stay in Chapaledfú, reducing my luggage to those items of most immediate use. My gardening clothes I must have, whilst I restricted myself to two changes for the evening; for everything else I took my trowel, secateurs, sketchpad and, along with Nostromo, a small bundle of books that I deemed essential: W. Robinson’s excellent volume on country-house landscapes, Garden Design by Madeline Ayer and a couple by my heroine, Gertrude Jekyll.

Supper was a hearty beef stew served with baked rice and a cup of red wine. Afterward, I sat by the fireplace with the old, blind mother and listened to her rambling stories, for it was her wish to impart the history of the land to which I had arrived. The wind had picked up and buffeted the cottage, causing the flames to shudder. I was glad Rivacoba insisted we not set out. The old woman spoke of the Desert Campaigns of Governor de Rosas and the native Mapuche Indians his men had massacred in order that civilization be brought to the Pampas. In turn, this had given rise to the great estancias where she found employ as a younger woman. All this was recounted with immense pride. I enquired whether she knew of Las Lágrimas. I noticed the station-master and his wife exchange a look, but the old woman claimed never to have heard of the place.

‘What colour is your hair, child?’ she asked later. ‘They tell me the English have locks the colour of straw.’

‘Some do, but mine is red.’

‘Red!’ This was a marvel to her; she wanted to touch it.

‘Mother,’ exclaimed the station-master. ‘Do not trouble our guest.’

‘It’s no bother,’ I replied, and I let her comb her gnarled fingers through my hair.

‘Red as of blood?’ she asked. ‘Or pimientos?’

‘No. Red, and gold and orange, like the leaves in autumn, my grandfather used to say.’

This description seemed to satisfy her, and after I retired to bed I was sure I could hear the old woman by the dying fire whispering to herself like the leaves in autumn. Leaves in autumn…

Across the Pampas

THE SUNSHINE THAT had witnessed my journey from Buenos Aires was no more when I woke the next morning. In its place low, misty clouds, the air so dank one felt it in one’s joints. We set out for Las Lágrimas first thing. Even as I made sure of my breakfast, Rivacoba was knocking at the cottage door. He carried out the belongings that I had condensed into the panniers and trunk.

‘What of the rest of my things?’ I asked.

‘They will follow.’

His response did not inspire my confidence and I wondered if I would see them again. I bade farewell to the stationmaster and his wife, thanking them for their hospitality and discreetly passed the former a note for five pesos, which embarrassed and pleased him in equal measure. To his blind mother I gave a small lock of my hair that earlier I had snipped off.

‘May God and the Virgin protect you out there,’ she said in thanks.

Rivacoba was waiting with three horses: one each for us to ride and a third, a stocky pony, which was already loaded with my luggage. My mount was a walnut-coloured mare of about fourteen hands. I took the reins and heaved myself up on to her, not side-saddle but with my legs either side of her flanks, the way Grandfather had taught me, and which found Rivacoba’s approval. The station-master waved us off. We took the horses at a walk through Chapaledfú. Few of its denizens had yet to rise. In the grey light, the place had a drear quality to it, as of a town in mourning. Perhaps in summer it was full of life and gaiety, but that August morning I was glad to be leaving. Beyond the last buildings were a score of fields, marked by fence posts, the black earth ploughed but unsown. Beyond that were the wastes. We cannot have ridden more than a quarter of an hour outside of Chapaledfú before I felt as remote as ever I have been.

Here was the Pampas proper.

At first glance the landscape was flat, the horizon a blade that separated grass from sky. On closer inspection, however, one noted slight undulations that offered the scenery a subtle rolling texture; in places it might be possible to find a sheltered spot. The one point not in contention was how endless it all seemed. It is difficult to convey to the reader just how vast the panorama was, though I imagine sailors must feel something of a like manner when far out at sea. Only two things broke the green monotony: clumps of the eponymous pampas grass (Cortaderia selloana) and, occasionally, small black islands of trees, or las quintas as the locals called these clusters. The whole day, the sky remained solid with cloud and gloom.

Having left town, we broke into a steady trot and thereafter Rivacoba alternated the pace between it and walking. No word passed between us for at least the first hour.

‘Does my horse have a name?’ I said by-and-by, to make conversation.

‘No.’

‘Then I shall call her “Dahlia”. It’s one of my favourite flowers.’

We continued on in silence.

A number of miles later I posed another question. ‘Shall we reach the estancia tonight?’

‘It’s too far.’

‘I am supposed to arrive to-day.’

‘As you said: blame the trains.’

‘I can ride faster than this,’ I ventured.

‘We’ll work the horses soon enough. But we could gallop the whole day and still not accomplish our journey by nightfall. You must learn there are two distances in the Pampas, Señorita. Far, and farther still.’ And that, pretty much, was the end of his loquaciousness.

We rode the length of the day and in that time met no other soul. That is not to say the Pampas was without life. The sky was lively with birds that flapped and darted over, some as neat as sparrows, others monstrous, and every size in between. ‘What’s that?’ I would ask, for my knowledge of ornithology is limited. ‘A viudita,’ came Rivacoba’s monotone reply. Or, ‘Chimango.’ The ground itself was more varied than first I perceived it to be. Grass, yes, an infinite quantity of it; but also speckles of tiny, white flowers; some species of wild artichoke with bluish-grey leaves; and an abundance of thistles. Most eye-catching of all was an occasional, deep-crimson flower that I took to be a miniature form of iris and that, had I been at leisure, I would have stopped to study. It grew in drifts and these appeared, from afar, not unimaginably like shoals of blood. When I quizzed my guide on them a tension hardened his features, he naming them as las flores del diablo. ‘Why that?’ I had asked.

‘Because they grow only where the devil treads.’

Later, we put the horses to a canter and that sense of excitement, of adventure, which had stolen upon me when first I laid eyes on the Pampas through the train window once more enlivened my heart. I felt intoxicated with it! The untamed beauty of the wilderness quickened my blood in a manner that would have disturbed the rest of my family, for they saw staidness as a virtue, my parents expecting – insisting upon – only the most conventional of lives for me: to be untroubled by curiosity or ambition, to marry and be dutiful. In short, to be everything Grandfather had exhorted me to reach beyond, marked as he was by a disdain for convention. He would have beamed with pride that I had journeyed so far from home, and all the more so at my Head Gardenership.

As the afternoon shortened, and we were again at a plodding walk, I grew fatigued, the muscles in my thighs, shoulders and, in particular, lower back aching. I yearned for a bath and fantasized myself at Las Lágrimas deep in hot, scented water. Behind the clouds the sun began to wester, casting the landscape in progressively darker shades that only heightened the emptiness of the place. The wind picked up and an overwhelming despondency took hold of me. To travel out here by oneself, I thought, would not be my preference and I tried to imagine how men like my guide, who must ride often without companionship, sustained themselves.

When dusk closed in, Rivacoba brought us to a halt in a slight depression. ‘We camp here tonight.’ He had been silent for so long his voice caused me to startle. I gratefully slipped off Dahlia and left her munching on the grass.

I presumed I would have a tent or some other kind of shelter, a presumption I was promptly disabused of. Rivacoba unloaded my meagre luggage and arranged it in a semi-circle to protect us from the wind. Then he unrolled a woven-grass mat and laid it on the ground over which he placed the sheepskin from underneath my saddle. Finally, I was given a thick poncho, maroon in colour, hircine in smell – and this rude bivouac was my bed for the night!

‘Is this how Don Paquito and his family travel?’ I demanded as Rivacoba unlooped a faggot of sticks from the pack-pony.

‘When I ride alone, I don’t have a fire,’ he replied, arranging the kindling on the ground. ‘But Señor Moyano insisted. You are lucky.’

My good fortune extended to strips of dried beef and a tin of beans for dinner, cooked in the flames and eaten as gusts of wind snapped around us. There was also yerba mate, the local tea, made from the dried leaves of a species of holly plant (Ilex paraguariensis, if I remember). Rivacoba took its preparation seriously, boiling water, then cramming a gourd with leaves before filling it to the brim with the hot liquid. He passed the gourd to me to drink first. I had sampled it previously in Buenos Aires and found it not to my palate. Sipping it on the Pampas it tasted as bitter as the greenest lemon, though the warming sensation that spread through my throat and chest was compensation.

Then I had buried myself inside my poncho and lain down for the night, watching the sparks from the fire whirl and dance and vanish into the darkness, a darkness so absolute it was hard to believe it real.

* * *

Next morning, I awakened stiff and damp into a half-gloom. My bladder pressed dully. The previous night I had slipped away to relieve myself. Despite the earliness of the hour, it was already too light to be afforded the same discretion. I vowed the next time I went to the lavatory it would be sitting down, enclosed by walls with a lock on the door and a chain to pull. For breakfast I had some day-old bread and a sip of coffee, mostly though I was keen to be on our way, and we broke camp as the sun began to rise. As with the previous day it was obscured by banks of thick, sullen cloud. I continued to wear the poncho in order that my body remain as snug as possible.

After what seemed like an eternity in the saddle, my spine feeling ever more brittle, I asked, ‘How much longer until we are there?’

‘We’re making good time.’ They were the first words to pass between us since leaving. ‘We will arrive by afternoon.’

I entered a kind of trance, the boundless grass, the unending sky, the regular bump of my bladder deadening my senses. The air developed an oppressiveness as if a deluge might unleash itself, albeit none came. My thoughts roved to Capitán Agramonte (for in due course I was told that the founder of the estancia, grandfather of Don Paquito, had held military rank) and the personality of a man who builds a house so far from civilization. These musings hurried my mind to my destination and I was gripped by an anxiety – one held at bay by the excitement of my new employment but now making its presence known – that I did not possess sufficient talent to take charge of the garden, I questioning why such a position had been bestowed on me in the first place. Thereafter it was, perhaps, inevitable that I thought back to the reading of Grandfather’s will for as much as I had put it out of mind, in moments of lower spirit its memory intruded.