6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

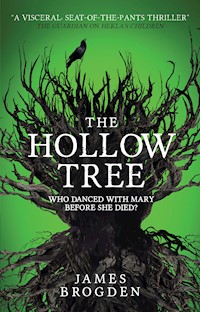

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

From the critically acclaimed author of Hekla's Children comes a dark and haunting tale of our world and the next.WHO DANCED WITH MARY BEFORE SHE DIED?After her hand is amputated following a tragic accident, Rachel Cooper suffers vivid nightmares of a woman imprisoned in the trunk of a hollow tree, screaming for help. When she begins to experience phantom sensations of leaves and earth with her lost hand, Rachel is terrified she is going mad… but then another hand takes hers, and the trapped woman is pulled into our world. She has no idea who she is, but Rachel can't help but think of the mystery of Oak Mary, a female corpse found in a hollow tree, and who was never identified. Three urban legends have grown up around the case; was Mary a Nazi spy, a prostitute or a gypsy witch? Rachel is desperate to learn the truth, but darker forces are at work. For a rule has been broken, and Mary is in a world where she doesn't belong…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also available from James Brogden and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1: Hand of Glory

1: Collision

2: Amputation

3: Recovery

4: Home

5: Rehabilitation

6: The Devil’s Coach-Horse

7: Prosthesis

8: Smoky

9: The Mary Oak

10: Infection

11: Gypsy Witch

12: The Stand-Off

13: Nazi Spy

14: The Mirror Box

15: Whore

16: Nightmares

2: Her Strong Enchantments

17: The Hospital

18: The Monument

19: Annabel

20: The Sight

21: Telling Tom

22: Noz

23: Static

24: Attack

25: Aftermath

26: Eline

27: The Hive

28: Fire

29: Asylum

30: The Small Man’s Prize

3: The Umbra

31: Near Death

32: Ghosts

33: Liaison

34: Gigi

35: The Tale of Black Meg

36: Shuffling Off

37: Unreal City

38: Appetites

39: Queen of Air and Darkness

40: Beatrice

41: The Hollow Tree

42: Cats for You

After

Afterword & Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

THE

HOLLOWTREE

Also available from James Brogden and Titan Books

Hekla’s Children

THE

HOLLOWTREE

JAMESBROGDEN

TITAN BOOKS

The Hollow Tree

Print edition ISBN: 9781785654404

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785654411

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2018

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2018 by James Brogden. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For ‘Bella’

MARY IN THE OAK TREECOLD AS COLD CAN BEWAITING FOR THE SKY TO FALLWHO WILL DANCE WITH ME?

TRADITIONAL BIRMINGHAM SKIPPING SONG

PROLOGUE

5th May 1945

NATURE ABHORS A VACUUM, OR SO IT IS SAID.

Sergeant Nicholas Raleigh and Corporal Rhys Hughes, both of the 9th Bomb Disposal Company, Royal Engineers, looked down at the smooth grey curve of steel, which broke the surface of the ground like a half-submerged sea monster. Surrounding them, the woods of the Lickey Hills were coming into leaf, bright with sunshine and the songs of birds. Meanwhile the bomb at their feet lay in the middle of it all, smug and insolent.

Sergeant Raleigh tilted his cap back and scratched his head, frowning. ‘Thousand-pounder, you suppose?’

‘Give or take an ounce,’ answered Corporal Hughes. He was sitting on a log and eating a cheese sandwich. Coming from a long line of Welsh miners, he’d taken to the Royal Engineers as if born to it. The vast majority of the unexploded ordnance they encountered was in Birmingham – spread out down at the foot of the hills in a grey haze – dealt with in a claustrophobic chaos of shattered buildings and the stench of burning, so he was enjoying the rare chance for a day out in the fresh air, and this place was as good as any for a picnic.

Raleigh didn’t seem to be appreciating the occasion. He was tall and rangy, and some might have said humourless with it, but surviving three years in a post of which the life expectancy was normally measured in months would do that to a man.

‘How long d’you reckon it’s been lying there?’ asked Hughes.

‘Last raid was back in forty-three,’ mused Raleigh. ‘So two years at least. They’ll have been trying to hit the Austin works. This one’s fallen much too short for a simple miss. Probably found things a bit hotter than they expected and dumped the weight before scarpering.’ He looked around. ‘Good news is that there’s nothing nearby.’

The Lickeys were a small range of hills to the south of Birmingham, a well-loved pleasure spot for city-dwellers looking to escape for day trips. A little over a mile from where they were standing, they could see the rooftops of the Austin works, pitted and painted green to look like ordinary farmland, where plane and machine parts for the war effort were made. The bomb had been found by a local gamekeeper who had alerted the Home Guard, and after checking to make sure there weren’t any more in the vicinity, a wide safety cordon had quickly been established. There might have been a few folks up here strolling or picnicking, but nowhere near danger, and other than the tram terminus and the Bilberry Tea Rooms at the bottom, the nearest human habitation was a good half-mile distant.

Corporal Hughes stood, brushing crumbs off his knees and tugging his uniform jacket down over his comfortably proportioned belly. ‘So are we going to blow it up then, Sarge, or not?’

Raleigh favoured him with a grim smile. ‘Why yes, Corporal, I rather think we are.’

* * *

The explosion was quite literally earth-shaking. Birds burst from the trees as a massive geyser of dirt, leaves and bits of tree fountained into the air and rained debris over a wide area, just as echoes of the detonation rolled out from the hills and over the city below. The silence that followed it was almost as deafening, and in that frozen moment fearful and wondering eyes turned to the sky. When the last fragments had fallen, Sergeant Raleigh and Corporal Hughes approached to inspect the damage.

Hughes placed his hands on his hips and gave a low, awed whistle. ‘Well that’ll clear your tubes and no mistake,’ he said.

It appeared as if God Himself had reached down and scooped out a sixty-foot wide handful of the hillside, leaving mounds of soil and rocks settling back into the crater in small avalanches, and splintered trees about the periphery. All that remained of the bomb was a twisted fragment of tail fin right at the very bottom and a litter of leaf debris that had been sucked into the crater by the blast’s initial vacuum.

‘You’re not wrong,’ Raleigh replied. ‘Right, let’s get the worst of it.’

They set to giving the immediate area a quick once-over for the largest and most obvious pieces of shrapnel, to be dumped in the crater and covered over. It would not be many more seasons before the woods reclaimed the spot as if nothing had ever happened; as if there had been no such things as war, or bombs. Already birdsong was slowly returning to the woods, filling the shocked silence.

Raleigh’s explorations were interrupted by a sudden cry of alarm from Hughes. ‘Sarge!’ he called. ‘Come quick!’

He found Corporal Hughes standing by the wide trunk of an old, dead oak tree. It had succumbed to either lightning or disease many years ago, and it had sheared off about seven feet from the ground, the remains of its limbs being little more than stark, fingerless stumps. The explosion had caused a great split to open up in it, a ragged fissure revealing that the trunk was hollow. At the bottom, in the shadow of a shallow well formed by the centre of the roots, he made out the deeper darkness of an eye socket staring back at him, and he recoiled.

‘Sweet Mary mother of God,’ he breathed.

The skull was lying on a pile of what he at first took to be old sticks, but then saw that they were ribs, leg bones, arm bones, the blocky lumps of vertebrae and a littering of fingers and toes. Stuffed into the hollow trunk, the corpse had been unable to fall and had simply rotted where it stood, the disarticulated remains collapsing through themselves and into a jumbled pile with the skull uppermost, staring up at the opening in the top of the broken trunk, which was forever beyond reach. There was fabric – too stained to tell the colour or whether it was shirt, trousers, or dress – and strands of dark hair still attached to the skull.

Hughes’ normally ruddy face was pale, and he was making strange gulping noises as his cheese sandwich threatened to rebel.

Both men had seen their fair share of death: bodies mangled and torn apart by German bombs, burned in fires, lacerated by shrapnel, crushed by fallen buildings, or any one of a dozen other ways a person could be killed. Neither could claim to be unaffected, but you took a deep breath and you carried on and you did your job. It was horrific, but explainable, and hard to think of as murder. It was war. This, however, was something entirely different, and coming as it did in what should have been a place of natural beauty and tranquillity gave it a particular sense of violation.

Hughes had managed to get himself under control. ‘Poor bugger. Who do you think he was?’

* * *

The police were called, but they could not discover the identity of the corpse beyond that it was the remains of a young woman. No witnesses came forward, and as the hills lay right on the boundary between the districts of Birmingham and Bromsgrove the investigation was passed back and forth between the two county constabularies until the threads of the investigation were hopelessly tangled and eventually lost altogether.

Still, nature abhors a vacuum, and no more so than the hole left by a soul taken friendless, anonymous and alone. Like air, or birdsong, myth floods in to fill the gap.

HAND OF GLORY

1

COLLISION

RACHEL COOPER STARES DOWN INTO THE BLACK GULF where the two steel hulls meet. A second ago they were approaching each other with the ponderous inevitability of thunderstorms, and she was scrabbling with slippery feet to get out of the way. In a second’s time they will rebound, and the two narrowboats will go on their ways, fifteen tons apiece. Her fascination lies in the fact that at this moment her lower left forearm is down there between the two of them, in the black canal water, and there is absolutely nowhere near enough space for something as thick as a human arm to be in such a place.

At this moment there is no pain. Pain will come later – that and much, much worse. For now there is only a dull surprise, as if to say ‘How on earth did my arm get down there?’

A stupid, meaningless accident, that is how.

* * *

Black Knight Boats operated a narrowboat hire company out of Stoke Pound on the Worcester and Birmingham canal, offering holidaymakers access to the heart of the country’s inland waterway network at a sedate four miles an hour, and a slightly eye-watering price tag. It catered mostly to empty-nesters and young middle-class families with illusions of enjoying a carefree and nomadic lifestyle, and it had taken Rachel months to convince Tom that it was their sort of thing.

‘I am not spending a week of my summer holiday farting around in the Black Country on a barge like some old man,’ he’d protested. ‘If you really want to see smashed-up warehouses and drowned shopping trolleys, get in the car, we’ll be there in half an hour.’ What was wrong with Greece? he’d wanted to know. It was hotter, it was cheaper, there was room service and a pool. Which meant it might as well have been anywhere, Rachel had countered; she wanted to see where she lived. Why didn’t she just look out the bloody window, then? he’d hmphed.

Variations on a theme, all through autumn last year.

She’d clinched it on the traditional Cooper family Boxing Day canal walk, that feat of domestic organisation which saw Tom, his mother Charlotte and his dad Spence, Gramps, sister Rosie and her husband Clive and brood of four, not to mention assorted dogs, bikes, hangers-on, boyfriends, girlfriends, and newer additions like Rachel herself, all pile into a small fleet of SUVs to walk off some of the festive bloat with a slow stroll up the canal to the Tardebigge Reservoir and back. Coming as she did from a much smaller family of just herself, her mother, an elderly great-grandmother known to all as ‘Gigi’ and a variety of distant uncles and aunts whom she rarely saw, Rachel loved immersing herself in the fuggy, jumbling chaos of Tom’s extended family, and even after three years was still surprised by how Charlotte welcomed her so unquestioningly and uncritically into the bosom of her tribe.

She and Tom had fallen back from the main mob and were walking with grandfather – fag on and fuck the doctors; Gramps had smoked since he was fourteen and what the bloody hell did they know about any of it – squelching along the muddy towpath, when they’d passed The Queens Head on the other side. It was busy with Boxing Day drinkers, many of them sitting muffled up in the beer garden under wide patio heaters.

Tom rubbed his hands against the chill. ‘I could just about do with a pint,’ he said.

Gramps snorted. ‘You don’t want to drink there. It’s all beer with goblins on and pulled pork and quinn-ower. Get yourself over to The Weighbridge at Alvechurch Marina. They do a good drop of ale.’

‘Could you get there by boat?’ Rachel wondered.

‘I should say so. It’s only a couple of miles further up. You’d pass a few decent pubs on the way.’

‘You don’t say.’ She nudged Tom. ‘Quite a few decent pubs, the man says. Just think, darling,’ she cooed, taking his arm and snuggling up against his shoulder. ‘A week-long pub crawl through the Black Country, lazy summer days. You, captain of your own vessel; me, lying on the roof, in the sun, in my bikini…’

Gramps sniffed. ‘I’d take her up on that, son, before she changes her mind.’

So they’d walked up to the reservoir and back, and kept going down to where Black Knight had their office and dozens of boats moored in the pound being refitted for the tourist season, and booked it then and there.

* * *

Her wedding ring, she realises, is on that hand, down there, in the dark. In the frozen moment between when everything was perfect and when everything will be crushed and broken. Part of her hopes that it slips off and falls into the silt, because at least that way there’s a chance that it might be rescued.

* * *

There was nothing lazy about the long, hot summer days that began that week. Tom was captain; that was non-negotiable. He even bought a hat. Rachel spent weeks putting together the most versatile wardrobe for a boating holiday – lots of Breton stripes and canvas.

A half-day’s induction by the Black Knight people had shown them how to drive the boat, perform basic maintenance checks and operate the canal locks, and it was then Rachel realised how badly she’d misunderstood the role of first mate. She’d thought she’d be lounging on the roof in a wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses with a glass of wine and the latest Joanne Harris, while Tom took care of the mechanical side of things. Her only experience of boats had been as a child on Edgbaston Reservoir, where she’d been taught to sail by her dad in light, easily handled Picos. She hadn’t factored in that a narrowboat would have to be manoeuvred while the locks were operated, and that this would be her job. Each lock had two pairs of massive swinging wooden gates that she had to open and shut, shoving at them like a donkey on a treadmill, and then she had to crank the sluice gates either open or closed with a metal device that looked like a tyre iron. Despite the fact that her desk job involved watching closed-circuit television monitors of a stretch of the M5 motorway for the Highways Agency and included the routine lifting of nothing heavier than a box-file, she kept herself reasonably fit by running – but lock gates involved a whole different set of muscles, and soon her back and arms were killing her.

What made it worse was that there were thirty of these locks on the Tardebigge Flight up into Birmingham. They had to stop halfway through for the night, during which she was good for nothing except demanding a back rub.

Stiffness and fatigue were mostly to blame for the accident.

They’d made it into Gas Street Basin right in the centre of Birmingham, which was busy with the multi-coloured liveries of dozens of boat companies, polished brass glittering in the sun, cascading colour from hanging baskets and flower boxes, streamers and pennants. There were no locks to open or close, so she sat in the bow and drank in the life and colour, but it was more of a navigational challenge for Tom at the stern, avoiding so many other craft, and she could see that they were drifting dangerously close to one of them. It was a café narrowboat, with large windows where tourists sat eating their lunch, cruising even more slowly than themselves, and the captain at the back could see that Tom was having trouble keeping a safe distance.

‘Oi!’ he shouted. ‘Watch yourself there!’

‘It’s okay, honey!’ she called to Tom. ‘I’ll fend us off!’

There was a long wooden pole clipped to the roof which she should have used, but that would have involved climbing all the way up there and dragging it back down, whereas she was sitting at the front already, and the side of the restaurant boat was coming right towards her. It wasn’t as if they were going to hit it outright – they were going to glance it at worst, and maybe not make contact at all. All she had to do was lean over and give it a good shove with both hands; mass and momentum being what they were, she wouldn’t have to deflect it by much, and it only needed an inch or two.

The boats lumbered together. She leaned out, placed both palms against the cold steel of the other hull – close enough to make momentary eye contact with a woman in glasses who raised her eyebrows in surprise – braced her feet, and pushed.

And her feet slipped.

Instead of her rubber-soled deck shoes she was wearing sandals that offered no purchase at all. She fell forward, head and both arms over the rail of her boat, and saw her own shocked reflection in the black, oily water. She flailed with her right hand, grabbed the rail, and started to pull herself back up from the rapidly narrowing gap.

And then it was now.

* * *

This moment, the lightless pivot of worlds – between one in which there is sun on water and flowers and wedding rings, and one in which she is a broken, crippled thing – passes, and cannot be recalled.

* * *

The boats bumped and parted as if there was nothing dramatic to see here, people, move along. The sun was no dimmer, the laughter and music no quieter. The woman in glasses got on with her lunch. Rachel pulled herself up properly with her right arm, dragging something heavy that seemed to have clamped itself to her left. When she looked down at what remained of her left arm just below the elbow, she began to scream.

2

AMPUTATION

THE SURGEON WAS AS APOLOGETIC AS THE URGENCY of her injury would allow. His ID badge said MR ADENSON, VASCULAR SURGEON but he was just another in a long list of concerned faces and forgotten names. Names, tags, worried frowns, and the elephant in the room: the massive swathed lump lying in bed beside her. There was an oxygen mask on her face and an IV in her good arm, killing the pain from the bad one. There was even, she discovered with disgust, a tube coming from between her legs. There wasn’t an inch of her that didn’t feel bruised or invaded or like it had been pulled off, twisted, and stuck back on upside down.

A question had been asked, but she couldn’t remember what it was.

‘Mum?’ Rachel moaned, and her mother was there, eyes puffy with weeping. ‘It all hurts. Everything. I just, I can’t…’ She couldn’t see her mother’s face properly; it was blurry, and she couldn’t work out why until Olivia wiped her face and she realised she was crying. ‘I’m sorry…’

‘Oh shh, my darling, whatever for?’

‘Because of Dad… and you said… you said you never wanted to, to see the inside of a hospital again…’

‘Shh, shh, it’s not your fault, my love. You’re hurt, not sick. It’s not your fault.’ Olivia turned to the doctor. ‘And you’re absolutely certain, then?’ she sniffed. ‘There’s no way of saving it?’

Mr Adenson shook his head. ‘The damage is simply too severe and too extensive, I’m afraid.’

Pulverised, they had said. Massive vascular damage. The two narrowboats hadn’t just bounced together and apart with her arm between them, they’d skidded off each other, doing to her flesh what two bricks rubbed together might do to a worm. Her hand hadn’t been squashed so much as smeared.

‘Mum,’ she said. ‘Let them do it.’

So they did it.

* * *

While they operated, she dreamed, but as is the way with such things she could only remember fragments of images when she woke up.

She dreamed of a tree.

It was an ugly tree, ancient and broken. At some point in its history the upper portion of its trunk and boughs had been shorn away – possibly through lightning or storm winds – leaving a squat, wide stump just higher than a tall woman’s head. But this had not killed the tree. A ragged crown of sapling limbs spread out from the blunt top, while thinner, sicklier shoots grew like the questing tendrils of a sea anemone further down the trunk, half-strangled by tumours of mistletoe and ivy, itself so old that its stalks were as thick and twisted and dry as the arms of old men. As she saw it, it came to her that the tree was hollow, and that someone was inside it, because from within that tangled mass she could hear a woman’s weeping.

Then a bare arm pushed free and reached out to her.

* * *

The next time Rachel woke up, the mask was gone, along with the catheter and the worst of the pain, but the IV was still in, and even under all the dressings it was obvious that the limb on the other side was a lot shorter, ending halfway down from the elbow. Thank God it isn’t mine, she thought.

There was another tube coming out of all the dressings, taking fluid away, as if the rest of her body were just some kind of processing plant for pain. The slightest shifting of position was enough to set her whole arm shrieking from shoulder to fingertips – never mind that her fingertips weren’t there any more. Whoever was in charge of the pain centres in her brain didn’t know that and was absolutely losing their shit, sounding the alarm that something was very, very wrong down there. Her throat was raw and her stomach rolled with nausea.

A hand stroked her brow: her mother murmuring, ‘Oh my poor darling, there there, oh my poor darling,’ over and over.

‘Mum?’ she croaked.

Her mother was instantly alert. ‘Yes, darling? Can I get you anything?’

Rachel nodded towards the bandaged stump lying next to her. ‘Whose arm is that?’ she asked. ‘What have they done with my hand?’

Olivia made a strange sort of choking noise and called for the nurse.

* * *

Gradually the nausea and disorientation passed, and Rachel was able to take clearer stock of her situation.

‘Where’s Tom?’ she asked her mother, who was still there and seemed not to have left for – how long was it? Rachel had lost track of time. It must only have been hours, but it felt like days. Maybe she’d always been here.

‘He’s waiting outside, darling. We didn’t want you to have to deal with too much too soon.’

‘I already am. Tell him he can come in.’

Tom came in, and like everyone else the first thing his eyes travelled to was her bandages.

‘Hey,’ she said.

‘Hey.’ His face was haggard with shadows. He was still wearing the same clothes – cargo shorts, deck shoes and a checked shirt and gilet vest – he’d worn on the boat. She’d teased him about it at the time, asking him when the next Young Farmers’ Association meeting was, back when any of that mattered, on the other side of before.

‘Oi, I’m up here.’ Rachel pointed to her face, and his eyes finally met hers. ‘At least you weren’t staring at my boobs.’

He smiled weakly. ‘This is all my fault,’ he started. ‘If I’d had the boat under better control…’

‘And if I hadn’t nagged you into it in the first place,’ she interrupted. ‘And if that other boat hadn’t been there. And if I’d been wearing proper shoes. And and and. Nothing you or I can say will make this grow back.’

‘I know, I just—’

‘It is what it is,’ she said, a little more harshly than she’d intended, but she didn’t have the energy to put up any kind of façade, either brave or gentle. ‘And apologies won’t make it better. I don’t need them. I will need your help, though.’

His eyes widened in surprise.

‘I know,’ she said. ‘You can count the number of times I’ve asked for that on one hand, which is ironic, since that’s all I’ve got now.’

She could almost hear her mother wince, but the smile Tom gave her was almost normal. There you are, she thought. There’s the man I need.

‘You’re incredible,’ he said.

‘No, I’m shit-scared and on some amazing drugs, but I have no choice. What’s happening with the boat?’

He blinked. ‘Seriously? You’re worried about that?’

‘I need something to think about.’ She glanced at her bandages. ‘Something… else. See if you can get, I don’t know, some kind of part refund for the days we didn’t use. Is all our stuff safe?’

‘It’s okay,’ Tom said, stroking her hair. ‘Dad’s got it under control. Oh, there’s this, though.’ He produced a small plastic grip-seal bag and showed her the contents. ‘They had to cut it off you when they… you know.’

It was her watch – the Mondaine she’d been given for her twenty-first. The strap was sheared through, the glass face was smashed and both the hands were gone. Ha, she thought. Beat you there. I only lost the one. Compared to losing her hand, a broken watch was nothing, but it reminded her of something far more important. ‘Oh shit!’ She turned shocked eyes to him. ‘My ring!’

He shrugged helplessly. ‘It wasn’t there.’

‘What do you mean it wasn’t there?’ She struggled to sit up higher, but that sent a spike of agony into her elbow despite the painkillers, and she cried out.

Olivia leapt to support her. ‘Darling, please, you mustn’t—’

‘What do you mean it wasn’t there?’ Rachel repeated between gasps of pain.

‘What do you want me to say?’ he asked. ‘I mean that it wasn’t there. If it had been, they’d have had to cut it off you too. It must have, I don’t know, snapped under the impact and dropped off. It’s probably at the bottom of the canal.’

‘No…’ she moaned. Her wedding ring. She’d never for one second begrudged the Cooper family’s self-made wealth which had allowed them to bankroll the wedding, but all the same she’d been fiercely proud of having at least arranged the rings – designed by an old school friend who had made good as part of an arts and crafts collective in the Jewellery Quarter. Its twin was on Tom’s hand – the one that was stroking her hair and trying to calm her – a simple band of white and yellow gold fused together.

‘Hey, it’s just a thing,’ he said. ‘Just a thing. It can be replaced. You can’t. You’re okay, and that’s the important thing.’

She gave a hollow laugh and gestured with her bandaged stump. ‘Yeah, what’s left of me.’

Eventually even mothers and husbands had to leave, and night settled on the recovery ward. It was a false darkness, though, like trying to sleep on a long-haul flight with all the lights down and your eye mask on but still aware of the restless souls all around you, busy with whispered conversations and soft footsteps along unseen corridors. Her hand was the same, buzzing and jittering in the empty space below her elbow as if refusing to accept that it didn’t exist any more. She was never going to be able to sleep, she thought, with her mind churning over the seismic effect this was going to have on her life, and the random shooting pains and starbursts of pins and needles.

But she did.

* * *

She surfaced from sleep just far enough to know that her mother was stroking her hand, telling her that everything was going to be all right without speaking; just loving, slow strokes across the back of her hand and down across her fingers.

But it must have been a dream, because when she opened her eyes the ward was still dark, and there was nobody sitting beside her bed.

And it was her missing left hand that had been so lovingly stroked.

3

RECOVERY

THE SURGEON MR ADENSON WAS TALL AND GANGLY, and his long fingers inspected her wound with as much delicacy and precision as any surgical instrument. Just behind him stood her physiotherapist, a small Nigerian woman who had been introduced to Rachel as Abayomi ‘Call me Yomi; it’s less embarrassing for all of us’ Akinsanya. She had a northern accent as broad as her smile but stood very still and self-contained with her arms folded. Rachel watched her suspiciously; she’d heard horror stories about physios from one of her mother’s golfing friends who’d had a knee replacement, and Rachel didn’t want to think about what plans for her arm lurked behind Yomi’s friendly smile. Rachel hissed as Adenson touched a tender spot.

‘Sorry about that,’ he frowned. ‘Sensitive?’

‘Just a bit.’

‘It’s bound to be at first. That’ll pass. There doesn’t appear to be too much swelling, though, which is a good thing. We’ll aim to have that drain out tomorrow afternoon if all goes well, and then a compression dressing to help keep it down.’

‘We’ll sort that hypersensitivity, too,’ nodded Yomi.

‘I hope so. It’s been going off like firecrackers all night.’

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!