7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

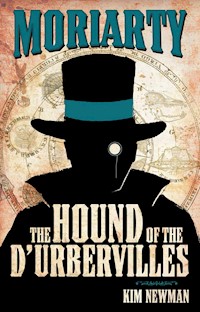

Imagine the twisted evil twins of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson and you have the dangerous duo of Professor James Moriarty - wily, snake-like, fiercely intelligent, unpredictable - and Colonel Sebastian 'Basher' Moran - violent, politically incorrect, debauched. Together they run London crime, owning police and criminals alike. Unravelling mysteries - all for their own gain. A hugely enjoyable, and fiercely clever romp from acclaimed novelist Kim Newman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Professor

MORIARTY

THE HOUND OF THED’URBERVILLES

KIM NEWMAN

TITAN BOOKS

Professor Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles

Print edition: ISBN: 9780857682833

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686015

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: September 2011

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Kim Newman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2011 Kim Newman

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

For Barry Forshaw

Also by Kim Newman from Titan Books:

ANNO DRACULA

ANNO DRACULA: THE BLOODY RED BARON (APRIL 2012)

PREFACE

Even during the global crisis which broke more famous financial institutions, the failure of Box Brothers was noisy. The private bank collapsed shortly after the arrest of Dame Philomela Box, Chief Executive Officer, on charges of fraudulent dealing. A warrant was also issued for her nephew, Colin Box. Press speculation that he had done a runner ended when his body was discovered in the boot of a burned-out Volvo on Havengore Island, Essex. Autopsy determined that Colin’s head had been sawn off and used as a football. No one has ever been charged with his murder, or those of two other bank officers found dead in the next six weeks.

Only after the CEO’s indictment could Box Brothers be called in print what it was, and always had been: the criminals’ bank. Founded in 1869, the family-owned business maintained premises in Moorgate, Gibraltar and Bermuda [1]. For nearly a century and a half, Box Brothers provided financial services (no questions asked) to law-breakers great and small. Their client list ranged from underworld gangs (and, from the 1960s on, terrorist cells) with enormous turnovers to conceal to lowly smash-and-grab merchants with bloodied cash deposits to make. As their still-live website euphemistically has it, Box Brothers’ twenty-first-century speciality was ‘offshore wealth management’ – which is to say, getting the loot out of the country. The house’s oldest service was the most confidential and secure storage facility in the City of London – which is to say, a box to keep the jewels or paintings (or, in several cases, people) out of sight until the heat died down.

At the time of writing, the Moorgate premises remain under twenty-four-hour armed guard as suits and countersuits regarding access to the safety deposit vault (where it is rumoured the trophies of several famous, unsolved thefts are to be found) are argued. Or not... since it seems the management were not above dipping into the till to pay for Dame Philomela’s passion for airships or Colin’s white rap label [2]. Lawrence and Harrington Box, the founders, would have been aghast at the decline from the standards set in their day. Their simple philosophy was scrupulous honesty. Clients were expected to set aside their habitual larceny in dealing with the bank, just as the brothers made no moral judgement about business brought to them.

Before the crash, my dealings with Box Brothers were limited.

While my A History of Silence: Victorian Crimes Against and By Women[3] was in proof, my cat went missing. When I left for work, Crippen was locked in the flat. When I came home, the flat was still locked but Crippen was gone. The next day, my Female Serial Killers seminar was interrupted by a special messenger making a recorded delivery of a lawyers’ letter which suggested I delete any mention of Box Brothers from my forthcoming book. I first read ‘if the offending material is not removed, no further legal action will be taken’ as a mistyping. Then I saw ‘no further legal action’ did not mean ‘no further action’. When I got home, Crippen was back, with a triangle snipped out of her ear. The offending reference consisted of a footnote in a chapter about nineteenth-century brothelkeepers [4]. I made the edit.

When Box Brothers fell, several hastily researched articles about the bank’s history appeared in the papers. Evidently, the bank no longer had the wherewithal to put pressure on journalists and historians. I assumed – not without Schadenfreude – that their in-house catnappers were busy avoiding larger, more dangerous animals. Widows and orphans and pension funds and small businessmen with accounts in Iceland run screaming to the government when their savings are in peril, but the sort of customer who banks with Box Brothers takes more direct action.

In July, 2009, I took a call in my office at Birkbeck College from Philomela Box’s private secretary, Henry Hassan.

‘Ms Temple, are you free to come into Dame Philomela’s office this afternoon for a consultation?’

‘On what?’ I asked.

‘Historical documents,’ he said.

Considering Crippen’s snipped ear, I was of a mind to tell Hassan where to file his historical documents. And to tell him it should be Professor Temple.

But it had been a boring week. The long summer vac was filled with faculty meetings about budget cuts. The only interesting PhD student I was supervising [5] was off working as a tour guide in Barcelona. So I agreed to visit the City.

Dame Philomela’s office was not in Holloway Prison. She was still in Moorgate. Windows smashed by an angry mob were boarded up. The building was guarded both by uniformed policemen and helmeted private security. A faction of anti-capitalist enthusiasts mounted a cosplay protest which had thinned over the months since the credit crunch started to bite. Ghost-masked young folks wore loose pyjamas decorated with broad arrows, and dragged about Jacob Marley chains of ledgers and strongboxes. Their slogans suggested they didn’t see Box Brothers as more criminal than any other bank.

Mr Hassan, the last loyal retainer, met me in a cavernous, dim reception room. Dustsheets were draped over the furniture. Loose wires showed where computers had once been plumbed in. Unfaded oblongs on the plush wallpaper marked the spots formerly taken by pictures which had walked out with suddenly unemployed staff. A cleaner had been arrested legging it down Silk Street with two Vernets and a Greuze in a Budgens ‘Bag for Life’.

I was ushered into an inner office.

A tall, thin woman came out from behind a desk to shake my hand. A red light flashed on her ankle bracelet.

‘Henry, get us espresso... if the plods haven’t taken the last of it along with every bloody thing else,’ said Dame Philomela. ‘I’ll have gin in mine, but the professor won’t, I’m sure.’

Mr Hassan retreated, backing out like a nervous courtier.

Dame Philomela’s office was hung with airship mobiles. She had a framed print of The Hindenburg disaster. On bookshelves where most bankers display leatherbound tomes of financial lore she had a complete set of Jeffrey Archer first editions. She was evidently a bit of a fan: in a photograph, she and Lord Archer wore matching flying helmets and her smile showed half a skull. I assumed he’d give her tips on how to get by in prison.

Dame Philomela was sixty. From experience with postgraduate students, I knew at once she was a functioning anorexic. She wore a tailored dark suit with a short skirt. Her long, straight black hair had a white streak – she must dye twice for the effect. Her only items of visible jewellery were a lapel-brooch in the shape of a dirigible and a discreet silver nose-stud.

The newspapers had made a lot out of Dame Philomela’s resemblance to a Disney cartoon villainess. I wondered if she didn’t cultivate the effect.

Her computer was gone. The Fraud Squad were going through thousands of Zeppelin .jpgs and .avis while looking for evidence. A brass-hinged wooden box stood on her desk where the monitor would have been.

‘Sit,’ she ordered.

I complied. She stood by her desk, long fingers on the box.

‘Do you know the legal status of items left undisturbed in safety deposit for, oh, eighty years?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Neither do I,’ Dame Philomela admitted. ‘That was Colin’s area. Bloody idiot. Anyway, I can tell you what we do with them here... it hardly matters any more. We use a master key our depositors don’t know about to open the box, and divvy up the contents if obviously valuable... or stick them in a sub-basement junk room if not. That started before my day. A necessity, with new clients coming in and needing secure space. There’s a waiting list – or, rather, there was – for our vault. Rather than go to the trouble of getting new boxes put in, it was easier to clear out lost causes and move on. Contrary to what you read in those awful rags, it’s not all crown jewels and wodges of banknotes. If you want a giggle, I’ve a collection of musty old letters used to blackmail people who’ve been dead so long no one could possibly care about their sad old secrets. Have you heard of Sebastian Moran?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘He was a minor Victorian. A soldier and explorer, big-game hunter. Implicated in something called the “Bagatelle Card Club Scandal”. He was caught cheating by a man called Adair, who was later shot dead. Moran was arrested for the murder, but didn’t hang... no one is quite sure how he got off, though he did go to prison for a few years. The only reason he’s remembered is because the Adair case was the first solved, after the socalled “great hiatus”, by...’

‘Good, yes, fine, you know your scoundrels,’ Dame Philomela interrupted. ‘Now, don’t go on, woman. Showing off is all it is. Anybody can Wikipedia this stuff now, so there’s no need to have it all up in your head to be spat out again. Very unattractive, it is. I’ve no earthly interest in the old dead bastard, anyway. Except for this.’

She took the box from her desk and gave it to me.

On the lid was a brass plate, inscribed: ‘Col. Sebastian Moran, 1st Bangalore Pioneers, Conduit Street.’

‘It’s not locked,’ said Dame Philomela.

Inside was a manuscript. Two separate sheafs, which I guessed were different drafts of the same material: a longhand version, neatly written on lined paper, and a typescript, with crossings-out and emendations in ink.

‘Is it authentic?’ she asked.

‘I couldn’t possibly say without closer examination.’

Dame Philomela looked annoyed. That cracked her tight face and brought out her inner hag.

‘Well then, you silly bitch, examine closely,’ said Dame Philomela.

I thought about leaving.

Mr Hassan came back with the espresso. It was criminally strong. I decided to stay, for a while.

‘I want to know if there’s money in this,’ said Dame Philomela. ‘And how quickly I can get it.’

‘I’ll have to take this away and have it looked at. Besides analysing the text, tests can be done on the paper and ink to get an estimate of the age.’

‘I should cocoa,’ snorted Dame Philomela. ‘This stays here. You can read it in the next room. Then tell me what I’ve got. And how much it’s worth.’

I took the typescript out of the tin, and riffled through it. It was a book-length manuscript, with numbered pages, divided into chapters. There was no title page, or author credit.

On the first few pages, someone had carefully inked out a recurring name and written in ‘Mahoney’ above the black patches. Then, the same hand scribbled ‘sod it, can’t be bothered!’ in the margin, and gave up on the pretence of concealing identity.

The name someone had thought briefly to hide was Moriarty.

‘Professor Moriarty?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ Dame Philomela said. ‘I dare say you’ve heard of him.’

‘A client of Box Brothers?’

‘One of the originals. So was Moran.’

‘He left a safety-deposit box?’

‘Yes. Inside was a pornographic deck of Edwardian playing cards I’ve put on eBay, a string of pearls I’m keeping for my old age, and this. Now, do you want to read it or not?’

I did. I have. And, with minimal editorial alteration, this is it.

Dame Philomela didn’t and doesn’t care if it’s an authentic memoir, though she was keen to establish that if it’s fake, it’s at least an old fake. No living author will come forward to claim royalties.

Tests were done. I confidently assert that this is the work of Colonel Sebastian Moran. Vocabulary and syntax are consistent with his published books, Heavy Game of the Western Himalayas (1881) and Three Months in the Jungle (1884)... though his tone in these memoirs is considerably less guarded. He incidentally settles a long-standing academic dispute by identifying himself as the anonymous author of My Nine Nights in a Harem (1879) [6]. The undated longhand pages were written between 1880 and 1910. Different paper and inks indicate the author worked intermittently, writing separate chapters over twenty years. It is probable sections were drafted in Prince Town Prison, where Moran was resident for some time after 1894.

Internal evidence suggests Moran intended to publish, perhaps inspired by the commercial success of others whose memoirs – many overlapping events he recounts – had already appeared. Of course, those authors did not confess to capital crimes in print, an issue which might have given Moran second thoughts. He was considering publication as late as 1923–4, when the typescript was made. We cannot definitively identify the person or persons who typed his manuscript for him [7], but can be sure it was not Moran – though the annotations are in his handwriting.

Without a research project which Dame Philomela, who is now serving a seven-year sentence in Askham Grange open prison, is unwilling to fund, a full assessment of the veracity of Moran’s memoirs is impossible. Given that the author characterises himself as a cheat, a liar, a villain and a murderer, we are entitled to ask whether he was as dishonest in autobiography as he was in everything else. However, it seems he felt – perhaps later in life – a compulsion to make an accurate record. Few in his time thought Sebastian Moran anything but a rogue, but his famous associate saw straight away that he was what we might now diagnose as an adrenalin junkie. When age kept him from more active pursuits, perhaps writing a book which could lead to him being hanged was a substitute for the thrill of hunting tigers or breaking laws. However, he was in healthy middle age when he began writing up the crimes of Professor Moriarty – and was in fact busy helping commit them. Where dates, names and places that can be checked are given, Moran is a reliable historian – more so than some of his less crooked contemporaries.

On the text: I have made few corrections to Moran’s spelling or syntax, except for consistency. He did go to Eton, after all. Some contemporaries took him for a fool, but he was an educated, well-read, intelligent man and articulate when he chose to be. The manuscript is overrun with hyphens and dashes which are pruned to some extent in the typescript, and have been pruned further by me. Moran held to nineteenth-century conventions (‘cow-boy’, ‘gas-light’, ‘were-wolf’) which would distract the modern eye. I have resisted a temptation to cut digressions or offhand references which raise tantalising matters upon which no further information is available. A thorough search of the vaults of Box Brothers has turned up no other Moran manuscripts – so we’re unlikely to find out more about the ‘Mystery of the Essex Werewolf’ or the ‘Affair of the Mountaineer’s Bum’.

Perhaps surprisingly, given his candour, Moran exercised a degree of self-censorship. Make no mistake, the Victorians could be as foul-mouthed as we are. Moran won an Army–Navy swearing contest held in Bombay in 1875, outlasting ‘the vilest bosun in the Fleet’ by a full half-hour of obscene profanity without repetition or hesitation, but with a great deal of deviation. However, in his manuscript, he blots out swear words. Some pages look like heavily redacted CIA intelligence reports. The typescript is clearer, but still tactful (‘c--t’, ‘f--k’, etc.). Where necessary, I have kept that archaism.

I have chosen not to include several passages which would prove offensive or stultifying to modern readers. Some material (dealing with race, sex or politics) exists in manuscript but not typescript, suggesting Moran himself had second thoughts. As a sometime pornographer, Moran’s accounts of sexual encounters run to dozens of detailed, unedifying pages; he writes about big-game hunting, horse-racing and card games in an identical manner. Where not directly germane to the narrative, I have trimmed paragraphs on these subjects. They are only of academic interest and this academic wasn’t especially interested – Heavy Game of the Western Himalayas has been out of print for over a hundred years for good reason. If Moran had been only a tiger hunter and libertine, he would be forgotten. As he admits, if he is remembered at all, it is because he was Moriarty’s lieutenant. In this edition of his memoirs, I have concentrated on that association, sparing the reader aspects of his life and times which now make Moran seem more appalling a human being than his inclinations towards larceny, duplicity and homicide.

Professor Christina Temple, BA, MA, PhD, FRHistS.

School of Social Sciences, History and Philosophy,

Department of History, Classics and Archaeology

Birkbeck College, London.

February 2011.

CONTENTS

Chapter One: A Volume in Vermilion

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

Chapter Two: A Shambles in Belgravia

I

II

III

Chapter Three: The Red Planet League

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Chapter Four: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

Chapter Five: The Adventure of the Six Maledictions

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

Chapter Six: The Greek Invertebrate

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

Chapter Seven: The Problem of the Final Adventure

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

CHAPTER ONE: A VOLUME IN VERMILION

I

I blame that rat-weasel Stamford, who was no better at judging character than at kiting paper. He later had his collar felt in Farnham, of all blasted places. If you want to pass French government bonds, you can’t afford to mix up your accents grave and your accents acute. Archie Stamford earns no sympathy from me. Thanks to him, I was first drawn into the orbit, the gravitational pull as he would have said, of Professor James Moriarty.

In 1880, your humble narrator was a vigorous, if scarred, forty. I should make a proper introduction of myself: Colonel Sebastian ‘Basher’ Moran, late of a school which wouldn’t let in an oik like you and a regiment which would as soon sack Newcastle as take Ali Masjid. I had an unrivalled bag of big cats and a fund of stories about blasting the roaring pests. I’d stood in the Khyber Pass and faced a surge of sword-waving Pathans howling for British blood, potting them like grouse in season. Nothing gladdens a proper Englishman’s heart – this one, at least – like the sight of a foreigner’s head flying into a dozen bloody bits. I’d dangled by a single-handed grip from an icy ledge in the upper Himalayas, with something huge and indistinct and furry stamping on my freezing fingers. I’d bent like an oak in a hurricane as Sir Augustus, the hated pater, spouted paragraphs of bile in my face, which boiled down to the proverbial ‘cut off without a penny’ business. Stuck to it too, the mean old swine. The family loot went to a society for providing Christian undergarments to the Ashanti, a bequest which had the delightful side effect of reducing my unmarriageable sisters to boarding-house penury.

I’d taken a dagger in the lower back from a harlot in Hyderabad and a pistol-ball in the knee from the Okhrana in Nijni-Novgorod. More to the point, I had recently been raked across the chest by the mad, wily old shetiger the hill-heathens called ‘Kali’s Kitten’.

None of that was preparation for Moriarty!

I had crawled into a drain after the tiger, whose wounds turned out to be less severe than I’d thought. Tough old hellcat! KK got playful with jaws and paws, crunching down my pith helmet like one of Carter’s Little Liver Pills, delicately shredding my shirt with razor claws, digging into the skin and drawing casually across my chest. Three bloody stripes. Sure I would die in that stinking tunnel, I was determined not to die alone. I got my Webley side arm unholstered and shot the hell-bitch through the heart. To make sure, I emptied all six chambers. After that chit in Hyderabad dirked me, I broke her nose for her. KK looked almost as aghast and infuriated at being killed. I wondered if girl and tigress were related. I had the cat’s rank dying breath in my face and her weight on me in that stifling hole. One more for the trophy wall, I thought. Cat dead, Moran not: hurrah and victory!

But KK nearly murdered me after all. The stripes went septic. Good thing there’s no earthly use for the male nipple, because I found myself down to just the one. Lots of grey stuff came out of me. So I was packed off back to England for proper doctoring.

It occurred to me that a concerted effort had been made to boot me out of the subcontinent. I could think of a dozen reasons for that, and a dozen clods in stiff collars who’d be happier with me out of the picture. Maiden ladies who thought tigers ought to be patted on the head and given treats. And the husbands, fathers and sweethearts of non-maiden ladies. Not to mention the 1st Bangalore Pioneers, who didn’t care to be reminded of their habit of cowering in ditches while Bloody Basher did three-fourths of their fighting for them.

Still, mustn’t hold a grudge, what? Sods, the lot of them. And that’s just the whites. As for the natives... well, let’s not get started on them, shall we? We’d be here ’til next Tuesday.

For me, a long sea cruise is normally an opportunity. There are always bored fellow passengers and underworked officers knocking around with fat notecases in their luggage. It’s most satisfying to sit on deck playing solitaire until some booby suggests a few rounds of cards and, why just to make it spicier, perhaps some trifling, sixpence-a-trick element of wager. Give me two months on any ocean in the world, and I can fleece everyone aboard from the captain’s lady to the bosun’s second-best bumboy, and leave each mark convinced that the ship is a nest of utter cheats with only Basher as the other honest hand in the game.

Usually, I embark sans sou and stroll down the gangplank at the destination, pockets a-jingle with the accumulated fortune of my fellow voyagers. I get a warm feeling from ambling through the docks, listening to clots explaining to the eager sorts who’ve turned up to greet them that, sadly, the moolah which would have saved the guano-grubbing business or bought the Bibles for the mission or paid for the wedding has gone astray on the high seas. This time, tragic to report, I was off sick, practically in quarantine. My nimble fingers were away from the pasteboards, employed mostly in scratching around the bandages while trying hard not to scratch the bandages themselves.

So, the upshot: Basher in London, out of funds. And the word was abroad. I was politely informed by a chinless receptionist at Claridge’s that my usual suite of rooms was engaged and that, unfortunately, no alternative was available, this being a busy wet February and all. If I hadn’t pawned my horsewhip, it would have got some use. If there’s any breed I despise more than natives, it’s people who work in bloody hotels. Thieves, the lot of them, or, what’s worse, sneaks and snitches. They talk among themselves, so it was no use trotting down the street and trying somewhere else.

I was on the point of wondering if I shouldn’t risk the Bagatelle Club, where, frankly, you’re not playing with amateurs. There’s the peril of wasting a whole evening shuffling and betting with other sharps who a) can’t be rooked so easily and b) are liable to be as cash-poor as oneself. Otherwise, it was a matter of beetling up and down Piccadilly all afternoon in the hope of spotting a ten-bob note in the gutter, or – if it came to it – dragging Farmer Giles into a sidestreet, splitting his head and lifting his poke. A comedown after Kali’s Kitten, but needs must...

‘It’s “Basher” Moran, isn’t it?’ drawled someone, prompting me to raise my sights from the gutter. ‘Still shooting anything that draws breath?’

‘Archibald Stamford, Esquire. Still practising auntie’s signature?’

I remembered Archie from some police cells in Islington. All charges dropped and apologies made, in my case. Being ‘mentioned in despatches’ carries weight with beaks, certainly more than the word of a tradesman in a celluloid collar you clean with India rubber. Six months jug for the fumbling forger, though. He’d been pinched trying to make a withdrawal from a relative’s bank account.

If clothes were anything to go by, Stamford had risen in his profession. Tiepin and cane, dove-grey morning coat, curly brimmed topper, and good boots. His whole manner, with that patronising hale-fellow-snooks-to-you tone, suggested he was in funds – which made him my long-lost friend.

The Criterion was handy, so I suggested we repair to the bar for drinks. The question of who paid for them would be settled when Archie was fuddleheaded from several whiskies. I fed him that shut-out-of-my-usual-suite line and considered a hard-luck story trading on my status as hero of the Jowaki Campaign – though I doubted an inky-fingered felon would put much stock in far-flung tales of imperial daring.

Stamford’s eyes shone, in a manner which reminded me unpleasantly of my late feline dancing partner. He sucked on his teeth, torn between saying something and keeping mum. It was a manner I would soon come to recognise as common to those in the employ of my soon-to-be benefactor.

‘As it happens, Bash old chap, I know a billet that might suit you. Comfortable rooms in Conduit Street, above Mrs Halifax’s establishment. You know Mrs H.?’

‘Used to keep a knocking-shop in Stepney? Arm-wrestler’s biceps and an eight-inch tongue?’

‘That’s the one. She’s West End now. Part of a combine, you might say. A thriving firm.’

‘What she sells is always in demand.’

‘True, but it’s not just the whoring. There’s other business. A man of vision, you might say, has done some thinking. About my line of trade, and Mrs Halifax’s, and, as it were, yours.’

I was about at the end of my rope with Archie. He was talking in a familiar, insinuating, creeping-round-behind-you-with-a-cosh manner I didn’t like. Implying that I was a tradesman did little for my ruddy temper. I was strongly tempted to give him one of my speciality thumps, which involves a neat little screw of my big fat regimental ring into the old eyeball, and see how his dove-grey coat looked with dirty great blobs of snotty blood down the front. After that, a quick fist into his waistcoat would leave him gasping, and give me the chance to fetch away his watch and chain, plus any cash he had on him. Of course, I’d check the spelling of ‘Bank of England’ on the notes before spending them. I could make it look like a difference of opinion between gentlemen. And no worries about it coming back to me. Stamford wouldn’t squeal to the peelers. If he wanted to pursue the matter I could always give him a second helping.

‘I wouldn’t,’ he said, as if he could read my mind.

That was a dash of Himalayan melt water to the face.

Catching sight of myself in the long mirror behind the bar, I saw my cheeks had gone a nasty shade of red. More vermilion than crimson. My fists were knotted, white-knuckled, around the rail. This, I understand, is what I look like before I ‘go off’. You can’t live through all I have without ‘going off’ from time to time. Usually, I ‘come to’ in handcuffs between policemen with black eyes. The other fellow or fellows or lady is too busy being carried away to hospital to press charges.

Still, a ‘tell’ is a handicap for a card player. And my red face gave warning.

Stamford smiled like someone who knows there’s a confederate behind the curtain with a bead drawn on the back of your neck and a finger on the trigger.

Libertè, hah!

‘Have you popped your guns, Colonel?’

I would pawn, and indeed have pawned, the family silver. I’d raise money on my medals, ponce my sisters (not that anyone would pay for the hymn-singing old trouts) and sell Royal Navy torpedo plans to the Russians... but a man’s guns are sacred. Mine were at the Anglo-Indian Club, oiled and wrapped and packed away in cherrywood cases, along with a kitbag full of assorted cartridges. If any cats got out of Regent’s Park Zoo, I’d be well set up to use a hansom for a howdah and track them along Oxford Street.

Stamford knew from my look what an outrage he had suggested. This wasn’t the red-hot pillar-box-faced Basher bearing down on him, this was the deadly icy calm of – and other folks have said this, so it’s not just me boasting – ‘the best heavy game shot that our Eastern Empire has produced’.

‘There’s a fellow,’ he continued, nervously, ‘this man of vision I mentioned. In a roundabout way, he is my employer. Probably the employer of half the folk in this room, whether they know it or not...’

He looked about. It was the usual shower: idlers and painted dames, jostling each other with stuck-on smiles, reaching sticky fingers into jacket pockets and up loose skirts, finely dressed fellows talking of ‘business’ which was no more than powdered thievery, a scattering of moon-faced cretins who didn’t know their size-thirteens gave them away as undercover detectives.

Stamford produced a card and handed it to me.

‘He’s looking for a shooter...’

The fellow could never say the right thing. I am a sportsman, not a keeper. A gun, not a gunslinger. A shot, not a shooter.

Still, game is game...

‘...and you might find him interesting.’

I looked down at the card. It bore the legend ‘Professor James Moriarty’, and an address in Conduit Street.

‘A professor, is it?’ I sneered. I pictured a dusty coot like the stick-men who’d bedevilled me through Eton (interminably) and Oxford (briefly). Or else a music-hall slickster, inflating himself with made-up titles. ‘What might he profess, Archie?’

Stamford was a touch offended, and took back the card. It was as if Archie were a new convert to papism and I’d farted during a sermon from Cardinal Newman.

‘You’ve been out of England a long time, Basher.’

He summoned the barman, who had been eyeing us with that fakir’s trick of knowing who was most likely, fine clothes or not, to do a runner.

‘Will you be paying now, sirs?’

Stamford held up the card and shoved it in the man’s face.

The barman went pale, dug into his own pocket to settle the tab, apologised, and backed off in terror.

Stamford just looked smug as he handed the card back to me.

II

‘You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive,’ said the Professor.

‘How the devil did you know that?’ I asked in astonishment.

His eyes caught mine. Cobra eyes, they say. Large, clear, cold, grey and fascinating. I’ve met cobras, and they aren’t half as deadly – trust me. I imagine Moriarty left off tutoring because his pupils were too terrified to con their two times table. I seemed to suffer his gaze for a full minute, though only a few seconds passed. It had been like that in the hug of Kali’s Kitten. I’d have sworn on a stack of well-thumbed copies of The Pearl that the mauling went on for an hour of pain, but the procedure was over inside thirty seconds. If I’d had a Webley on my hip, I might have shot the Professor in the heart on instinct – though it’s my guess bullets wouldn’t dare enter him. He had a queer unhealthy light about him. Not unhealthy in himself, but for everybody else.

Suddenly, pacing distractedly about the room, head wavering from side to side as if he had two dozen extra flexible bones in his neck, he began to rattle off facts.

Facts about me.

‘...you are retired from your regiment, resigning at the request of a superior to avoid the mutual disgrace of dishonourable discharge; you have suffered a serious injury at the claws of a beast, are fully recovered physically, but worry your nerve might have gone; you are the son of a late Minister to Persia and have two sisters, your only living relatives beside a number of unacknowledged half-native illegitimates; you are addicted, most of all to gambling, but also to sexual encounters, spirits, the murder of animals and the fawning of a duped public; most of the time, you blunder through life like a bull, snatching and punching to get your own way, but in moments of extreme danger you are possessed by a strange serenity which has enabled you to survive situations that would have killed another man; in fact, your true addiction is to danger, to fear – only near death do you feel alive; you are unscrupulous, amoral, habitually violent and, at present, have no means of income, though your tastes and habits require a constant inflow of money...’

Throughout this performance, I took in Professor James Moriarty. Tall, stooped, hair thin at the temples, cheeks sunken, wearing a dusty (no, chalky) frock coat, sallow as only an indoorsman can be; yellow cigarette stain between his first and second fingers, teeth to match. And, obviously, very pleased with himself.

He reminded me of Gladstone gone wrong. With just a touch of a hill-chief who had tortured me with fire ants.

But I had no patience with his lecture. I’d eaten enough of that from the pater for a lifetime.

‘Tell me something I don’t know,’ I interrupted...

The Professor was unpleasantly surprised. It was as if no one had ever dared break into one of his speeches before. He halted in his tracks, swivelled his skull and levelled those shotgun-barrel-hole eyes at me.

‘I’ve had this done at a bazaar,’ I continued. ‘It’s no great trick. The fortuneteller notices tiny little things and makes dead-eye guesses – you can tell I gamble from the marks on my cuffs, and was in Afghanistan by the colour of my tan. If you spout with enough confidence, you score so many hits the bits you get wrong – like that tommyrot about being addicted to danger – are swallowed and forgotten. I’d expected a better show from your advance notices, “Professor”.’

He slapped me across the face, swiftly, with a hand like wet leather.

Now, I was amazed.

I knew I was vermilion again, and my dukes went up.

Moriarty whirled, coat-tails flying, and his boot-toe struck me in the groin, belly and chest. I found myself sat in a deep chair, too shocked to hurt, pinned down by wiry, strong hands which pressed my wrists to the armrests. That dead face was close up to mine and those eyes horribly filled the view.

That calm he mentioned came on me. And I knew I should just sit still and listen.

‘Only an idiot guesses or reasons or deduces,’ the Professor said, patiently. He withdrew, which meant I could breathe again and become aware of how much pain I was in. ‘No one comes into these rooms unless I know everything about him that can be found out through the simple means of asking behind his back. The public record is easily filled in by looking in any one of a number of reference books, from the Army Guide to Who’s Who. But all the interesting material comes from a man’s enemies. I am not a conjurer, Colonel Moran. I am a scientist.’

There was a large telescope in the room, aimed out of the window. On the walls were astronomical charts and a collection of impaled insects. A long side table was piled with brass, copper and glass contraptions I took for parts of instruments used in the study of the stars or navigation at sea. That shows I wasn’t yet used to the Professor. Everything about him was lethal, and that included his assorted bric-a-brac.

It was hard to miss the small kitten pinned to the mantelpiece by a jackknife. The skewering had been skilfully done, through the velvety skinfolds of the haunches. The animal mewled from time to time, not in any especial pain.

‘An experiment with morphine derivatives,’ he explained, following my gaze. ‘Tibbles will let us know when the effect wears off.’

Moriarty posed by his telescope, bony fingers gripping his lapel.

I remembered Stamford’s manner, puffed up with a feeling he was protected but tinged with terror. At any moment, the great power to which he had sworn allegiance might capriciously or justifiably turn on him with destructive ferocity. I remembered the Criterion barman digging into his own pocket to settle our bill – which, I now realised, was as natural as the Duke of Clarence gumming his own stamps or Florence Nightingale giving sixpenny knee-tremblers in D’Arblay Street.

Beside the Professor, that ant-man was genteel.

‘Who are you?’ I asked, unaccustomed to the reverential tone I heard in my own voice. ‘What are you?’

Moriarty smiled his adder’s smile.

And I relaxed. I knew. My destiny and his wound together. It was a sensation I’d never got before upon meeting a man. When I’d had it from women, the upshot ranged from disappointment to attempted murder. Understand me, Professor James Moriarty was a hateful man, the most hateful, hateable, creature I have ever known, not excluding Sir Augustus and Kali’s Kitten and the Abominable Bloody Snow-Bastard and the Reverend Henry James Prince [1]. He was something man-shaped that had crawled out from under a rock and moved into the manor house. But, at that moment, I was his, and I remain his forever. If I am remembered, it will be because I knew him. From that day on, he was my father, my commanding officer, my heathen idol, my fortune and terror and rapture.

God, I could have done with a stiff drink.

Instead, the Professor tinkled a silly little bell and Mrs Halifax trotted in with a tray of tea. One look and I could tell she was his, too. Stamford had understated the case when he said half the folk in the Criterion Bar worked for Moriarty. My guess is that, at bottom, the whole world worked for him. They’ve called him the Napoleon of Crime, but that’s just putting what he is, what he does, in a cage. He’s not a criminal, he is crime itself, sin raised to an art form, a church with no religion but rapine, a God of Evil. Pardon my purple prose, but there it is. Moriarty brings things out in people, things from their depths.

He poured me tea.

‘I have had an eye on you for some time, Colonel Moran. Some little time. Your dossier is thick, in here...’

He tapped his concave temple.

This was literally true. He kept no notes, no files, no address book or appointment diary. It was all in his head. Someone who knows more than I do about sums told me that Moriarty’s greatest feat was to write The Dynamics of an Asteroid, his magnum opus, in perfect first draft. From his mind to paper, with no preliminary notations or pencilled workings, never thinking forward to plan or skipping back to correct. As if he were singing ‘one long, pure note of astro-mathematics, like a castrato nightingale delivering a hundred-thousand-word telegram from Prometheus.’

‘You have come to these rooms and have already seen too much to leave...’

An ice-blade slid through my ribs into my heart.

‘...except as, we might say, one of the family’.

The ice melted, and I felt tingly and warm. With the phrase, ‘one of the family’, he had arched his eyebrow invitingly.

He stroked Tibbles, who was starting to leak and make nasty little noises.

‘We are a large family, many cells with no knowledge of each other, devoted to varied pursuits. Most, though not all, are concerned with money. I own that other elements of our enterprise interest me far more. We are alike in that. You only think you gamble for money. In fact, you gamble to lose. You even hunt to lose, knowing you must eventually be eaten by a predator more fearsome than yourself. For you, it is an emotional, instinctual, sensual thrill. For me, there are intellectual, aesthetic, spiritual rewards. But, inconveniently, money must come into it. A great deal of money.’

As I said, he had me sold already. If a great deal of money was to be had, Moran was in.

‘The Firm is available for contract work. You understand? We have clients who bring problems to us. We solve them, using whatever skills we have to hand. If there is advantage to us beyond the agreed fee, we seize it...’

He made a fist in the air, as if squeezing a microbe to death.

‘...if our interests happen to run counter to those of the client, we settle the matter in such a way that is ultimately convenient to us, while our patron does not realise precisely what has happened. This, also, you understand?’

‘Too right, Professor,’ I said.

‘Good. I believe we shall have satisfaction of each other.’

I sipped my tea. Too milky, too pale. It always is after India. I think they put curry powder in the pot out there, or else piddle in the sahib’s crockery when he’s not looking.

‘Would you care for one of Mrs Halifax’s biscuits?’ he asked, as if he were the vicar entertaining the chairwoman of the beneficent fund. ‘Vile things, but you might like them.’

I dunked and nibbled. Mrs H. was a better madame than baker. Which led me to wonder what fancies might be buttered up in the rooms below the Professor’s lair.

‘Colonel Moran, I am appointing you as head of one of our most prestigious divisions. It is a post for which you are eminently qualified by achievement and aptitude. Technically, you are superior to all in the Firm. You are expected to take up residence here, in this building. A generous salary comes with the position. And profit participation in, ah, “special projects”. One such matter is at hand, and we shall come to it when we receive our next caller, Mister – no, not Mister, Elder – Elder Enoch J. Drebber of Cleveland, Ohio.’

‘I’m flattered,’ I responded. ‘A “generous salary” would solve my problems, not to mention the use of a London flat. But, Moriarty, what is this division you wish me to head? Why am I such a perfect fit for it? What, specifically, is its business?’

Moriarty smiled again.

‘Did I omit to mention that?’

‘You know damn well you did!’

‘Murder, my dear Moran. Its business is murder.’

III

Barely ten minutes after my appointment as Chief Executive Director of Homicide, Ltd., I was awaiting our first customer.

I mused humorously that I might offer an introductory special, say a garrotting thrown in gratis with every five poisonings. Perhaps there should be a half-rate for servants? A sliding scale of fees, depending on the number of years a prospective victim might reasonably expect to have lived had a client not retained our services?

I wasn’t yet thinking the Moriarty way. Hunting I knew to be a serious avocation. Murder was for bounders and cosh-men, hardly even killing at all. I’m not squeamish about taking human life: Quakers don’t get decorated after punitive actions against Afghan tribesmen. But not one of the heap of unwashed heathens I’d laid in the dust in the service of Queen and Empire had given me a quarter the sport of the feeblest tiger I ever bagged.

Shows you how little I knew then.

The Professor chose not to receive Elder Drebber in his own rooms, but made use of the brothel parlour. The room was well supplied with plushly upholstered divans, laden at this early evening hour with plushly upholstered tarts. It occurred to me that my newfound position with the Firm might entitle me to handle the goods. I even took the trouble mentally to pick out two or three bints who looked ripe for what ladies the world over have come to know as the Basher Moran Special. Imagine the Charge of the Light Brigade between silk sheets, or over a dresser table, or in an alcove of a Ranee’s Palace, or up the Old Kent Road, or... well, anywhere really.

As soon as I sat down, the whores paid attention, cooing and fluttering like doves, positioning themselves to their best advantage. As soon as the Professor walked in, the flock stood down, finding minute imperfections in fingernails or hair that needed rectifying.

Moriarty looked at the dollies and then at me, constructing something on his face that might have passed for a salacious, comradely leer but came out wrong. The bare-teeth grin of a chimpanzee, taken for a cheery smile by sentimental zoo visitors, is really a frustrated snarl of penned, homicidal fury. The Professor also had an alien range of expression, which others misinterpreted at their peril.

Mrs Halifax ushered in our American callers.

Enoch J. Drebber – why d’you think Yankees are so keen on those blasted middle initials? – was a barrel-shaped fellow, sans moustache but with a fringe of tight black curls all the way round his face. He wore simple, expensive black clothes and a look of stern disapproval.

The girls ignored him. I sensed he was on the point of fulminating.

I didn’t need one of the Professor’s ‘background checks’ to get Drebber’s measure. He was one of those odd godly bods who get voluptuous pleasure from condemning the fleshly failings of others. As a Mormon, he could bag as many wives as he wanted – on-tap whores and unpaid skivvies corralled together. His right eye roamed around the room, on the scout for the eighth or ninth Mrs Drebber, while his left was fixed straight ahead at the Professor.

With him came a shifty cove by the name of Brother Stangerson who kept quiet but paid attention.

‘Elder Drebber, I am Professor Moriarty. This is Colonel Sebastian Moran, late of the First Bangalore...’

Drebber coughed, interrupting the niceties.

‘You’re who to see in this city if a Higher Law is called for?’

Moriarty showed empty hands.

‘A man must die, and that’s the story,’ Drebber said. ‘He should have died in South Utah, years ago. He’s a murderer, plain and flat, and an abductor of women. Hauled out his six-gun and shot Bishop Dyer, in front of the whole town. A crime against God. Then fetched away Jane Withersteen, a good Mormon woman, and her adopted child, Little Fay. He threw down a mountain on his pursuers, crushing Elder Tull and many good Mormon men [2]. Took away gold that was rightful property of the Church, stole it right out of the ground. The Danite Band have been pursuing him ever since...’

‘The Danites are a cabal within the Church of Latter-day Saints,’ Moriarty explained.

‘God’s good right hand is what we are,’ insisted Drebber. ‘When the laws of men fail, the unworthy must be smitten, as if by lightning.’

I got the drift. The Danites were cossacks, assassins and vigilantes wrapped up in a Bible name. Churches, like nations, need secret police forces to keep the faithful in line.

‘Who is this, ah, murderer and abductor?’ I asked.

‘His name, if such a fiend deserves a name, is Lassiter. Jim Lassiter.’

This was clearly supposed to get a reaction. The Professor kept his own council. I admitted I’d never heard of the fellow.

‘Why, he’s the fastest gun in the South West. Around Cottonwoods, they said he struck like a serpent, drawing and discharging in one smooth, deadly motion. Men he killed were dead before they heard the sound of the shot. Lassiter could take a man’s eye out at three-hundred yards with a pistol.’

That’s a fairy story. Take it from someone who knows shooting. A side arm is handy for close work, as when, for example, a tiger has her talons in your tit. With anything further away than a dozen yards, you might as well throw the gun as fire it.

I kept my scepticism to myself. The customer is always right, even in the murder business.

‘This Lassiter,’ I ventured. ‘Where might he be found?’

‘In this city,’ Drebber decreed. ‘We are here, ah, on the business of the Church. The Danites have many enemies, and each of us knows them all. I was half expecting to come across another such pestilence, a cur named Jefferson Hope who need not concern you, but it was Lassiter I happened upon, walking in your Ly-cester Square on Sunday afternoon. I saw the Withersteen woman first, then the girl, chattering for hot chestnuts. I knew the apostate for who she was. She has been thrice condemned and outcast...’

‘You said she was abducted,’ put in the Professor. ‘Now you imply she is with Lassiter of her own will?’

‘He’s a Devil of persuasion, to make a woman refuse an Elder of the Church and run off with a damned Gentile. She has no mind of her own, like all women, and cannot fully be blamed for her sins...’

If Drebber had a horde of wives around the house and still believed that, he was either very privileged or very unobservant.

‘Still, she must be brought to heel. Though the girl will do as well. A warm body must be taken back to Utah, to come into an inheritance.’

‘Cottonwoods,’ said Moriarty. ‘The ranch, the outlying farms, the cattle, the racehorses and, thanks to those inconveniently upheld claims, the fabulous gold mines of Surprise Valley.’

‘The Withersteen property, indeed. When it was willed to her by her father, a great man, it was on the understanding she would become the wife of Elder Tull, and Cottonwoods would come into the Church. Were it not for this Lassiter, that would have been the situation.’

Profits, not parsons, were behind this.

‘The Withersteen property will come to the girl, Fay, upon the death of the adoptive mother?’

‘That is the case.’

‘One or other of the females must be alive?’

‘Indeed so.’

‘Which would you prefer? The woman or the girl?’

‘Jane Withersteen is the more steeped in sin, so there would be a certain justice...’

‘...if she were topped too,’ I finished his thought.

Elder Drebber wasn’t comfortable with that, but nodded.

‘Are these three going by their own names?’

‘They are not,’ said Drebber, happier to condemn enemies than contemplate his own schemes against them. ‘This Lassiter has steeped his women in falsehood, making them bear repeated false witness, over and over. That such crimes should go unpunished is an offence to God Himself...’

‘Yes, yes, yes,’ I said. ‘But what names are they using, and where do they live?’

Drebber was tugged out of his tirade, and thought hard.

‘I caught only the false name of Little Fay. The Withersteen woman called her “Rache”, doubtless a diminutive for the godly name “Rachel”...’

‘Didn’t you think to tail these, ah, varmints, to their lair?’

Drebber was offended. ‘Lassiter is the best tracker the South West has ever birthed. Including Apaches. If I dogged him, he’d be on me faster’n a rattler on a coon.’

The Elder’s vocabulary was mixed. Most of the time, he remembered to sound like a preacher working up a lather against sin and sodomy. When excited, he sprinkled in terms which showed him up for – in picturesque ‘Wild West’ terms – a back-shooting, claim-jumping, cow-rustling, waterhole-poisoning, horse-thieving, side-winding owlhoot son of a bitch.

‘Surely he thinks he’s safe here and will be off his guard?’

‘You don’t know Lassiter.’

‘No, and, sadly for us all, neither do you. At least, you don’t know where he hangs his hat.’

Drebber was deflated.

Moriarty said, ‘Mr and Mrs James Lassiter and their daughter Fay currently reside at The Laurels, Streatham Hill Road, under the names Jonathan, Helen and Rachel Laurence.’

Drebber and I looked at the Professor. He had enjoyed showing off.

Even Stangerson clapped a hand to his sweaty forehead.

‘Considering there’s a fabulous gold mine at issue, I consider fifty thousand a fair price for contriving the death of Mr Laurence,’ said Moriarty, as if putting a price on a fish supper. ‘With an equal sum for his lady wife.’

Drebber nodded again, once. ‘The girl comes with the package?’

‘I think a further hundred thousand for her safekeeping, to be redeemed when we give her over into the charge of your church.’

‘Another hundred thousand pounds?’

‘Guineas, Elder Drebber.’

He thought about it, swallowed, and stuck out his paw.

‘Deal, Professor...’

Moriarty regarded the American’s hand. He turned and Mrs Halifax was beside him with a salver bearing a document.

‘Such matters aren’t settled with a handshake, Elder Drebber. Here is a contract, suitably circumlocutionary as to the nature of the services Colonel Moran will be performing, but meticulously exact in detailing payments entailed and the strict schedule upon which monies are to be transferred. It’s legally binding, for what that’s worth, but a contract with us is enforceable under what you have referred to as a Higher Law...’

The Professor stood by a lectern, which bore an open, explicitly illustrated volume of the sort found in establishments like Mrs Halifax’s for occasions when inspiration flags. He unrolled the document over a coloured plate, then plucked a pen from an inkwell and presented it to Drebber.

The Elder made a pretence of reading the rubric and signed.

Professor Moriarty pressed a signet ring to the paper, impressing a stylised M below Drebber’s dripping scrawl.

The document was whisked away.

‘Good day, Elder Drebber.’

Moriarty dismissed the client, who backed out of the room.

‘What are you waiting for?’ I said to Stangerson, who stuck on the hat he had been fiddling with and scarpered.

One of the girls giggled at his departure, then remembered herself and pretended it was a hiccough. She paled under her rouge at the Professor’s sidelong glance.

‘Colonel Moran, have you given any thought to hunting a Lassiter?’

IV

A jungle is a jungle, even if it’s in Streatham and is made up of villas named after shrubs.

In my coat pocket I had my Webley.

If I were one of those cowboys, I’d have notched the barrel after killing Kali’s Kitten. Then again, even if I only counted white men and tigers, I didn’t own any guns with a barrels long enough to keep score. A gentleman doesn’t need to list his accomplishments or his debts, since there are always clerks to keep tally. I might not have turned out to be a pukka gent, but I was flogged and fagged at Eton beside future cabinet ministers and archbishops, and some skins you never shed.

It was bloody cold, as usual in London. Not raining, no fog – which is to say, no handy cover of darkness – but the ground chill rose through my boots and a nasty wind whipped my face like wet pampas grass.

The only people outside this afternoon were hurrying about their business with scarves around their ears, obviously part of the landscape. I had decided to toddle down and poke around, as a preliminary to the business in hand. Call it a recce.

Before setting out, I’d had the benefit of a lecture from the Professor. He had devoted a great deal of thought to murder. He could have written the Baedeker’s or Bradshaw’s of the subject. It would probably have to be published anonymously – A Complete Guide to Murder, by ‘A Distinguished Theorist’ – and then be liable to seizure or suppression by the philistines of Scotland Yard.

‘Of course, Moran, murder is the easiest of all crimes, if murder is all one has in mind. One simply presents one’s card at the door of the intended victim, is ushered into his sitting room and blows his or, in these enlightened times her, brains out with a revolver. If one has omitted to bring along a firearm, a poker or candlestick will serve. Physiologically, it is not difficult to kill another person, to perform outrages upon a human corpus which will render it a human corpse. Strictly speaking, this is a successful murder. Of course, then comes the second, far more challenging part of the equation: getting away with it.’

I’d been stationed across the road from The Laurels for a quarter of an hour, concealed behind bushes, before I noticed I was in Streatham Hill Rise not Streatham Hill Road. This was another Laurels, with another set of residents. This was a boarding house for genteel folk of a certain age. I was annoyed enough, with myself and the locality, to consider potting the landlady just for the practice.

If I held the deeds to this district and the Black Hole of Calcutta, I’d live in the Black Hole and rent out Streatham. Not only was it beastly cold, but stultifyingly dull. Row upon monotonous row of The Lupins, The Laburnums, The Leilandii and The Laurels. No wonder I was in the wrong spot.

‘It is a little-known fact that most murderers don’t get away with it. They are possessed by an emotion – at first, perhaps, a mild irritation about the trivial habit of a wife, mother, master or mistress. This develops over time, sprouting like a seed, to the point when only the death of another will bring peace. These murderers go happy to the gallows, free at last of their victim’s clacking false teeth or unconscious chuckle or penny-pinching. We shun such as amateurs. They undertake the most profound action one human being can perform upon another, and fail to profit from the enterprise.’