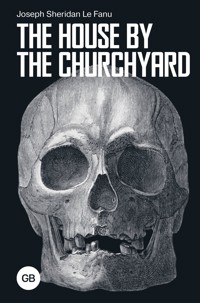

2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

We are going to talk, if you please, in the ensuing chapters, of what was going on in Chapelizod about a hundred years ago. A hundred years, to be sure, is a good while; but though fashions have changed, some old phrases dropped out, and new ones come in; and snuff and hair-powder, and sacques and solitaires quite passed away-yet men and women were men and women all the same-as elderly fellows, like your humble servant, who have seen and talked with rearward stragglers of that generation-now all and long marched off-can testify, if they will.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 950

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The House by the Churchyard

The House by the Churchyard A PROLOGUE.CHAPTER I.CHAPTER II.CHAPTER III.CHAPTER IV.CHAPTER V.CHAPTER VI.CHAPTER VII.CHAPTER VIII.CHAPTER IX.CHAPTER X.CHAPTER XI.CHAPTER XII.CHAPTER XIII.CHAPTER XIV.CHAPTER XV.CHAPTER XVI.CHAPTER XVII.CHAPTER XVIII.CHAPTER XIX.CHAPTER XX.CHAPTER XXI.CHAPTER XXII.CHAPTER XXIII.CHAPTER XXIV.FOOTNOTE:CHAPTER XXV.CHAPTER XXVI.CHAPTER XXVII.CHAPTER XXVIII.CHAPTER XXIX.CHAPTER XXX.CHAPTER XXXI.CHAPTER XXXII.CHAPTER XXXIII.CHAPTER XXXIV.CHAPTER XXXV.CHAPTER XXXVI.CHAPTER XXXVII.CHAPTER XXXVIII.CHAPTER XXXIX.CHAPTER XL.CHAPTER XLI.CHAPTER XLII.CHAPTER XLIII.CHAPTER XLIV.CHAPTER XLV.CHAPTER XLVI.CHAPTER XLVII.CHAPTER XLVIII.CHAPTER XLIX.CHAPTER L.CHAPTER LI.CHAPTER LII.CHAPTER LIII.CHAPTER LIV.CHAPTER LV.CHAPTER LVI.CHAPTER LVII.CHAPTER LVIII.CHAPTER LIX.CHAPTER LX.CHAPTER LXI.CHAPTER LXII.CHAPTER LXIII.CHAPTER LXIV.CHAPTER LXV.CHAPTER LXVI.CHAPTER LXVII.CHAPTER LXVIII.CHAPTER LXIX.CHAPTER LXX.CHAPTER LXXI.CHAPTER LXXII.CHAPTER LXXIII.CHAPTER LXXIV.CHAPTER LXXV.CHAPTER LXXVI.CHAPTER LXXVII.CHAPTER LXXVIII.CHAPTER LXXIX.CHAPTER LXXX.CHAPTER LXXXI.CHAPTER LXXXII.CHAPTER LXXXIII.CHAPTER LXXXIV.CHAPTER LXXXV.CHAPTER LXXXVI.CHAPTER LXXXVII.CHAPTER LXXXVIII.CHAPTER LXXXIX.CHAPTER XC.CHAPTER XCI.CHAPTER XCII.CHAPTER XCIII.CHAPTER XCIV.CHAPTER XCV.CHAPTER XCVI.CHAPTER XCVII.CHAPTER XCVIII.CHAPTER XCIX.CopyrightThe House by the Churchyard

Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

A PROLOGUE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

THE NAMELESS COFFIN.

hree vehicles with flambleaux, and the clang and snorting of horses came close to the church porch, and there appeared suddenly, standing within the disc of candle-light at the church door, before one would have thought there was time, a tall, very pale, and peculiar looking young man, with very large, melancholy eyes, and a certain cast of evil pride in his handsome face.

John Tracy lighted the wax candles which he had brought, and Bob Martin stuck them in the sockets at either side of the cushion, on the ledge of the pew, beside the aisle, where the prayer-book lay open at 'the burial of the dead,' and the rest of the party drew about the door, while the doctor was shaking hands very ceremoniously with that tall young man, who had now stepped into the circle of light, with a short, black mantle on, and his black curls uncovered, and a certain air of high breeding in his movements. 'He reminded me painfully of him who is gone, whom we name not,' said the doctor to pretty Lilias, when he got home; he has his pale, delicately-formed features, with a shadow of his evil passions too, and his mother's large, sad eyes.'

And an elderly clergyman, in surplice, band, and white wig, with a hard, yellow, furrowed face, hovered in, like a white bird of night, from the darkness behind, and was introduced to Dr. Walsingham, and whispered for a while to Mr. Irons, and then to Bob Martin, who had two short forms placed transversely in the aisle to receive what was coming, and a shovel full of earth—all ready. So, while the angular clergyman ruffled into the front of the pew, with Irons on one side, a little in the rear, both books open; the plump little undertaker, diffusing a steam from his moist garments, making a prismatic halo round the candles and lanterns, as he moved successively by them, whispered a word or two to the young gentleman [Mr. Mervyn, the doctor called him], and Mr. Mervyn disappeared. Dr. Walsingham and John Tracy got into contiguous seats, and Bob Martin went out to lend a hand. Then came the shuffling of feet, and the sound of hard-tugging respiration, and the suppressed energetic mutual directions of the undertaker's men, who supported the ponderous coffin. How much heavier, it always seems to me, that sort of load than any other of the same size!

A great oak shell: the lid was outside in the porch, Mr. Tressels was unwilling to screw it down, having heard that the entrance to the vault was so narrow, and apprehending it might be necessary to take the coffin out. So it lay its length with a dull weight on the two forms. The lead coffin inside, with its dusty black velvet, was plainly much older. There was a plate on it with two bold capitals, and a full stop after each, thus;—

R. D. obiit May 11th, A.D. 1746. ætat 38.

And above this plain, oval plate was a little bit of an ornament no bigger than a sixpence. John Tracy took it for a star, Bob Martin said he knew it to be a Freemason's order, and Mr. Tressels, who almost overlooked it, thought it was nothing better than a fourpenny cherub. But Mr. Irons, the clerk, knew that it was a coronet; and when he heard the other theories thrown out, being a man of few words he let them have it their own way, and with his thin lips closed, with their changeless and unpleasant character of an imperfect smile, he coldly kept this little bit of knowledge to himself.

Earth to earth (rumble), dust to dust (tumble), ashes to ashes (rattle).

And now the coffin must go out again, and down to its final abode.

The flag that closed the entrance of the vault had been removed. But the descent of Avernus was not facile, the steps being steep and broken, and the roof so low. Young Mervyn had gone down the steps to see it duly placed; a murky, fiery light; came up, against which the descending figures looked black and cyclopean.

Dr. Walsingham offered his brother-clergyman his hospitalities; but somehow that cleric preferred returning to town for his supper and his bed. Mervyn also excused himself. It was late, and he meant to stay that night at the Phœnix, and to-morrow designed to make his compliments in person to Dr. Walsingham. So the bilious clergyman from town climbed into the vehicle in which he had come, and the undertaker and his troop got into the hearse and the mourning coach and drove off demurely through the town; but once a hundred yards or so beyond the turnpike, at such a pace that they overtook the rollickingcortègeof the Alderman of Skinner's Alley upon the Dublin road, all singing and hallooing, and crowing and shouting scraps of banter at one another, in which recreations these professional mourners forthwith joined them; and they cracked screaming jokes, and drove wild chariot races the whole way into town, to the terror of the divine, whose presence they forgot, and whom, though he shrieked from the window, they never heard, until getting out, when the coach came to a stand-still, he gave Mr. Tressels a piece of his mind, and that in so alarming a sort, that the jolly undertaker, expressing a funereal concern at the accident, was obliged to explain that all the noise came from the scandalous party they had so unfortunately overtaken, and that 'the drunken blackguards had lashed and frightened his horses to a runaway pace, singing and hallooing in the filthy way he heard, it being a standing joke among such roisterers to put quiet tradesmen of his melancholy profession into a false and ridiculous position.' He did not convince, but only half puzzled the ecclesiastic, who muttering, 'credat Judæus,' turned his back upon Mr. Tressels, with an angry whisk, without bidding him good-night.

Dr. Walsingham, with the aid of his guide, in the meantime, had reached the little garden in front of the old house, and the gay tinkle of a harpsichord and the notes of a sweet contralto suddenly ceased as he did so; and he said—smiling in the dark, in a pleasant soliloquy, for he did not mind John Tracy,—old John was not in the way—'She always hears my step—always—little Lily, no matter how she's employed,' and the hall-door opened, and a voice that was gentle, and yet somehow very spirited and sweet, cried a loving and playful welcome to the old man.

CHAPTER III.

MR. MERVYN IN HIS INN.

he morning was fine—the sun shone out with a yellow splendour—all nature was refreshed—a pleasant smell rose up from tree, and flower, and earth. The now dry pavement and all the row of village windows were glittering merrily—the sparrows twittered their lively morning gossip among the thick ivy of the old church tower—here and there the village cock challenged his neighbour with high and vaunting crow, and the bugle notes soared sweetly into the air from the artillery ground beside the river.

Moore, the barber, was already busy making his morning circuit, servant men and maids were dropping in and out at the baker's, and old Poll Delany, in her weather-stained red hood, and neat little Kitty Lane, with her bright young careful face and white basket, were calling at the doors of their customers with new laid eggs. Through half-opened hall doors you might see the powdered servant, or the sprightly maid in her mob-cap in hot haste steaming away with the red japanned 'tea kitchen' into the parlour. The town of Chapelizod, in short, was just sitting down to its breakfast.

Mervyn, in the meantime, had had his solitary meal in the famous back parlour of the Phœnix, where the newspapers lay, and all comers were welcome. He was by no means a bad hero to look at, if such a thing were needed. His face was pale, melancholy, statuesque—and his large enthusiastic eyes, suggested a story and a secret—perhaps a horror. Most men, had they known all, would have wondered with good Doctor Walsingham, why, of all places in the world, he should have chosen the little town where he now stood for even a temporary residence. It was not a perversity, but rather a fascination. His whole life had been a flight and a pursuit—a vain endeavour to escape from the evil spirit that pursued him—and a chase of a chimera.

He was standing at the window, not indeed enjoying, as another man might, the quiet verdure of the scene, and the fragrant air, and all the mellowed sounds of village life, but lost in a sad and dreadful reverie, when in bounced little red-faced bustling Dr. Toole—the joke and the chuckle with which he had just requited the fat old barmaid still ringing in the passage—'Stay there, sweetheart,' addressed to a dog squeezing by him, and which screeched out as he kicked it neatly round the door-post.

'Hey, your most obedient, Sir,' cried the doctor, with a short but grand bow, affecting surprise, though his chief object in visiting the back parlour at that moment was precisely to make a personal inspection of the stranger. 'Pray, don't mind me, Sir,—your—ho! Breakfast ended, eh? Coffee not so bad, Sir; rather good coffee, I hold it, at the Phœnix. Cream very choice, Sir?—I don't tell 'em so though (a wink); it might not improve it, you know. I hope they gave you—eh?—eh? (he peeped into the cream-ewer, which he turned towards the light, with a whisk). And no disputing the eggs—forty-eight hens in the poultry yard, and ninety ducks in Tresham's little garden, next door to Sturk's. They make a precious noise, I can tell you, when it showers. Sturk threatens to shoot 'em. He's the artillery surgeon here; and Tom Larkin said, last night, it's because they only dabble and quack—and two of a trade, you know—ha! ha! ha! And what a night we had—dark as Erebus—pouring like pumps, by Jove. I'll remember it, I warrant you. Out on business—a medical man, you know, can't always choose—and near meeting a bad accident too. Anything in the paper, eh? ho! I see, Sir, haven't read it. Well, and what do you think—a queer night for the purpose, eh? you'll say—we had a funeral in the town last night, Sir—some one from Dublin. It was Tressel's men came out. The turnpike rogue—just round the corner there—one of the talkingest gossips in the town—and a confounded prying, tattling place it is, I can tell you—knows the driver; and Bob Martin, the sexton, you know—tells me there were two parsons, no less—hey! Cauliflowers in season, by Jove. Old Dr. Walsingham, our rector, a pious man, Sir, and does a world of good—that is to say, relieves half the blackguards in the parish—ha! ha! when we're on the point of getting rid of them—but means well, only he's a little bit lazy, and queer, you know; and that rancid, raw-boned parson, Gillespie—how the plague did they pick him up?—one of the mutes told Bob 'twas he. He's from Donegal; I know all about him; the sourest dog I ever broke bread with—and mason, if you please, by Jove—a prince pelican! He supped at the Grand Lodge after labour, one night—you'renot a mason, I see; tipt you the sign—and his face was so pinched, and so yellow, by Jupiter, I was near squeezing it into the punch-bowl for a lemon—ha! ha! hey?'

Mervyn's large eyes expressed a well-bred surprise. Dr. Toole paused for nearly a minute, as if expecting something in return; but it did not come.

So the doctor started afresh, never caring for Mervyn's somewhat dangerous looks.

'Mighty pretty prospects about here, Sir. The painters come out by dozens in the summer, with their books and pencils, and scratch away like so many Scotchmen. Ha! ha! ha! If you draw, Sir, there's one prospect up the river, by the mills—upon my conscience—but you don't draw?'

No answer.

'A little, Sir, maybe? Just for a maggot, I'll wager—likemygood lady, Mrs. Toole.' A nearer glance at his dress had satisfied Toole that he was too much of a maccaroni for an artist, and he was thinking of placing him upon the lord lieutenant's staff. 'We've capital horses here, if you want to go on to Leixlip,' (where—this between ourselves and the reader—during the summer months His Excellency and Lady Townshend resided, and where, the old newspapers tell us, they 'kept a public day every Monday,' and he 'had a levée, as usual, every Thursday.') But this had no better success.

'If you design to stay over the day, and care for shooting, we'll have some ball practice on Palmerstown fair-green to-day. Seven baronies to shoot for ten and five guineas. One o'clock, hey?'

At this moment entered Major O'Neill, of the Royal Irish Artillery, a small man, very neatly got up, and with a decidedly Milesian cast of countenance, who said little, but smiled agreeably—

'Gentlemen, your most obedient. Ha, doctor; how goes it?—anything new—anythingontheFreeman?'

Toole had scanned that paper, and hummed out, as he rumpled it over,—'nothing—very—particular. Here's Lady Moira's ball: fancy dresses—all Irish; no masks; a numerous appearance of the nobility and gentry—upwards of five hundred persons. A good many of your corps there, major?'

'Ay, Lord Blackwater, of course, and the general, and Devereux, and little Puddock, and——'

'Sturkwasn't,' with a grin, interrupted Toole, who bore that practitioner no good-will. 'A gentleman robbed, by two foot-pads, on Chapelizod-road, on Wednesday night, of his watch and money, together with his hat, wig and cane, and lies now in a dangerous state, having been much abused; one of them dressed in an old light-coloured coat, wore a wig. By Jupiter, major, if I was in General Chattesworth's place, with two hundred strapping fellows at my orders, I'd get a commission from Government to clear that road. It's too bad, Sir, we can't go in and out of town, unless in a body, after night-fall, but at the risk of our lives. [The convivial doctor felt this public scandal acutely.] The bloody-minded miscreants, I'd catch every living soul of them, and burn them alive in tar-barrels. By Jove! here's old Joe Napper, of Dirty-lane's dead. Plenty of dry eyes afterhim. And stay, here's another row.' And so he read on.

In the meantime, stout, tightly-braced Captain Cluffe of the same corps, and little dark, hard-faced, and solemn Mr. Nutter, of the Mills, Lord Castlemallard's agents, came in, and half a dozen more, chiefly members of the club, which met by night in the front parlour on the left, opposite the bar, where they entertained themselves with agreeable conversation, cards, backgammon, draughts, and an occasional song by Dr. Toole, who was a florid tenor, and used to give them, 'While gentlefolks strut in silver and satins,' or 'A maiden of late had a merry design,' or some other such ditty, with a recitation by plump little stage-stricken Ensign Puddock, who, in 'thpite of hith lithp,' gave rather spirited imitations of some of the players—Mossop, Sheridan, Macklin, Barry, and the rest. So Mervyn, the stranger, by no means affecting this agreeable society, took his cane and cocked-hat, and went out—the dark and handsome apparition—followed by curious glances from two or three pairs of eyes, and a whispered commentary and criticism from Toole.

So, taking a meditative ramble in 'His Majesty's Park, the Phœnix;' and passing out at Castleknock gate, he walked up the river, between the wooded slopes, which make the valley of the Liffey so pleasant and picturesque, until he reached the ferry, which crossing, he at the other side found himself not very far from Palmerstown, through which village his return route to Chapelizod lay.

CHAPTER IV.

THE FAIR-GREEN OF PALMERSTOWN.

here were half-a-dozen carriages, and a score of led horses outside the fair-green, a precious lot of ragamuffins, and a good resort to the public-house opposite; and the gate being open, the artillery band, rousing all the echoes round with harmonious and exhilarating thunder, within—an occasional crack of a 'Brown Bess,' with a puff of white smoke over the hedge, being heard, and the cheers of the spectators, and sometimes a jolly chorus of many-toned laughter, all mixed together, and carried on with a pleasant running hum of voices—Mervyn, the stranger, reckoning on being unobserved in the crowd, and weary of the very solitude he courted, turned to his right, and so found himself upon the renowned fair-green of Palmerstown.

It was really a gay rural sight. The circular target stood, with its bright concentric rings, in conspicuous isolation, about a hundred yards away, against the green slope of the hill. The competitors in their best Sunday suits, some armed with muskets and some with fowling pieces—for they were not particular—and with bunches of ribbons fluttering in their three-cornered hats, and sprigs of gay flowers in their breasts, stood in the foreground, in an irregular cluster, while the spectators, in pleasant disorder, formed two broad, and many-coloured parterres, broken into little groups, and separated by a wide, clear sweep of green sward, running up from the marksmen to the target.

In the luminous atmosphere the men of those days showed bright and gay. Such fine scarlet and gold waistcoats—such sky-blue and silver—such pea-green lutestrings—and pink silk linings—and flashing buckles—and courtly wigs—or becoming powder—went pleasantly with the brilliant costume of the stately dames and smiling lasses. There was a pretty sprinkling of uniforms, too—the whole picture in gentle motion, and the bugles and drums of the Royal Irish Artillery filling the air with inspiring music.

All the neighbours were there—merry little Dr. Toole in his grandest wig and gold-headed cane, with three dogs at his heels,—he seldom appeared without this sort of train—sometimes three—sometimes five—sometimes as many as seven—and his hearty voice was heard bawling at them by name, as he sauntered through the town of a morning, and theirs occasionally in short screeches, responsive to the touch of his cane. Now it was, 'Fairy, you savage, let that pig alone!' a yell and a scuffle—'Juno, drop it, you slut'—or 'Cæsar, you blackguard, where are you going?'

'Look at Sturk there, with his lordship,' said Toole, to the fair Magnolia, with a wink and a nod, and a sneering grin. 'Good natured dog that—ha! ha! You'll find he'll oust Nutter at last, and get the agency; that's what he's driving at—always undermining somebody.' Doctor Sturk and Lord Castlemallard were talking apart on the high ground, and the artillery surgeon was pointing with his cane at distant objects. 'I'll lay you fifty he's picking holes in Nutter's management this moment.'

I'm afraid there was some truth in the theory, and Toole—though he did not remember to mention it—had an instinctive notion that Sturk had an eye upon the civil practice of the neighbourhood, and was meditating a retirement from the army, and a serious invasion of his domain.

Sturk and Toole, behind backs, did not spare one another. Toole called Sturk a 'horse doctor,' and 'the smuggler'—in reference to some affair about French brandy, never made quite clear to me, but in which, I believe, Sturk was really not to blame; and Sturk called him 'that drunken little apothecary'—for Toole had a boy who compounded, under the rose, his draughts, pills, and powders in the back parlour—and sometimes, 'that smutty little ballad singer,' or 'that whiskeyfied dog-fancier, Toole.' There was no actual quarrel, however; they met freely—told one another the news—their mutual disagreeabilities were administered guardedly—and, on the whole, they hated one another in a neighbourly way.

Fat, short, radiant, General Chattesworth—in full, artillery uniform—was there, smiling, and making little speeches to the ladies, and bowing stiffly from his hips upward—his great cue playing all the time up and down his back, and sometimes so near the ground when he stood erect and threw back his head, that Toole, seeing Juno eyeing the appendage rather viciously, thought it prudent to cut her speculations short with a smart kick.

His sister Rebecca—tall, erect, with grand lace, in a splendid stiff brocade, and with a fine fan—was certainly five-and-fifty, but still wonderfully fresh, and sometimes had quite a pretty little pink colour—perfectly genuine—in her cheeks; command sat in her eye and energy on her lip—but though it was imperious and restless, there was something provokingly likeable and even pleasant in her face. Her niece, Gertrude, the general's daughter, was also tall, graceful—and, I am told, perfectly handsome.

'Be the powers, she's mighty handsome!' observed 'Lieutenant Fireworker' O'Flaherty, who, being a little stupid, did not remember that such a remark was not likely to pleasure the charming Magnolia Macnamara, to whom he had transferred the adoration of a passionate, but somewhat battered heart.

'They must not see with my eyes that think so,' said Mag, with a disdainful toss of her head.

'They say she's not twenty, but I'll wager a pipe of claret she's something to the back of it,' said O'Flaherty, mending his hand.

'Why, bless your innocence, she'll never see five-and-twenty, and a bit to spare,' sneered Miss Mag, who might more truly have told that tale of herself. 'Who's that pretty young man my Lord Castlemallard is introducing to her and old Chattesworth?' The commendation was a shot at poor O'Flaherty.

'Hey—so, my Lord knows him!' says Toole, very much interested. 'Why that's Mr. Mervyn, that's stopping at the Phœnix. A. Mervyn,—I saw it on his dressing case. See how she smiles.'

'Ay, she simpers like a firmity kettle,' said scornful Miss Mag.

'They're very grand to-day, the Chattesworths, with them two livery footmen behind them,' threw in O'Flaherty, accommodating his remarks to the spirit of his lady-love.

'That young buck's a man of consequence,' Toole rattled on; 'Miss does not smile on everybody.'

'Ay, she looks as if butter would not melt in her mouth, but I warrant cheese won't choke her,' Magnolia laughed out with angry eyes.

Magnolia's fat and highly painted parent—poor bragging, good-natured, cunning, foolish Mrs. Macnamara, the widow—joined, with a venemous wheeze in the laugh.

Those who suppose that all this rancour was produced by mere feminine emulations and jealousy do these ladies of the ancient sept Macnamara foul wrong. Mrs. Mack, on the contrary, had a fat and genial soul of her own, and Magnolia was by no means a particularly ungenerous rival in the lists of love. But Aunt Rebecca was hoitytoity upon the Macnamaras, whom she would never consent to more than half-know, seeing them with difficulty, often failing to see them altogether—though Magnolia's stature and activity did not always render that easy. To-day, for instance, when the firing was brisk, and some of the ladies uttered pretty little timid squalls, Miss Magnolia not only stood fire like brick, but with her own fair hands cracked off a firelock, and was more complimented and applauded than all the marksmen beside, although she shot most dangerously wide, and was much nearer hitting old Arthur Slowe than that respectable gentleman, who waved his hat and smirked gallantly, was at all aware. Aunt Rebecca, notwithstanding all this, and although she looked straight at her from a distance of only ten steps, yet she could not see that large and highly-coloured heroine; and Magnolia was so incensed at her serene impertinence that when Gertrude afterwards smiled and courtesied twice, she only held her head the higher and flung a flashing defiance from her fine eyes right at that unoffending virgin.

Everybody knew that Miss Rebecca Chattesworth ruled supreme at Belmont. With a docile old general and a niece so young, she had less resistance to encounter than, perhaps, her ardent soul would have relished. Fortunately for the general it was only now and then that Aunt Becky took a whim to command the Royal Irish Artillery. She had other hobbies just as odd, though not quite so scandalous. It had struck her active mind that such of the ancient women of Chapelizod as were destitute of letters—mendicants and the like—should learn to read. Twice a week her 'old women's school,' under that energetic lady's presidency, brought together its muster-roll of rheumatism, paralysis, dim eyes, bothered ears, and invincible stupidity. Over the fire-place in large black letters, was the legend, 'BETTER LATE THAN NEVER!' and out came the horn-books and spectacles, and to it they went with their A-B ab, etc., and plenty of wheezing and coughing. Aunt Becky kept good fires, and served out a mess of bread and broth, along with some pungent ethics, to each of her hopeful old girls. In winter she further encouraged them with a flannel petticoat apiece, and there was besides a monthly dole. So that although after a year there was, perhaps, on the whole, no progress in learning, the affair wore a tolerably encouraging aspect; for the academy had increased in numbers, and two old fellows, liking the notion of the broth and the 6d. a month—one a barber, Will Potts, ruined by a shake in his right hand, the other a drunken pensioner, Phil Doolan, with a wooden leg—petitioned to be enrolled, and were, accordingly, admitted. Then Aunt Becky visited the gaols, and had a knack of picking up the worst characters there, and had generally two or three discharged felons on her hands. Some people said she was a bit of a Voltarian, but unjustly; for though she now and then came out with a bouncing social paradox, she was a good bitter Church-woman. So she was liberal and troublesome—off-handed and dictatorial—not without good nature, but administering her benevolences somewhat tyrannically, and, for the most part, doing more or less of positive mischief in the process.

And now the general ('old Chattesworth,' as the scornful Magnolia called him) drew near, with his benevolent smirk, and his stiff bows, and all his good-natured formalities—for the general had no notion of ignoring his good friend and officer, Major O'Neill, or his sister or niece—and so he made up to Mrs. Macnamara, who arrested a narrative in which she was demonstrating to O'Flaherty the general's lineal descent from old Chattesworth—an army tailor in Queen Anne's time—and his cousinship to a live butter dealer in Cork—and spicing her little history with not a very nice epigram on his uncle, 'the counsellor,' by Dr. Swift, which she delivered with a vicious chuckle in the 'Fireworker's' ear, who also laughed, though he did not quite see the joke, and said, 'Oh-ho-ho, murdher!'

The good Mrs. Mack received the general haughtily and slightly, and Miss Magnolia with a short courtesy and a little toss of her head, and up went her fan, and she giggled something in Toole's ear, who grinned, and glanced uneasily out of the corner of his shrewd little eye at the unsuspicious general and on to Aunt Rebecca; for it was very important to Dr. Toole to stand well at Belmont. So, seeing that Miss Mag was disposed to be vicious, and not caring to be compromised by her tricks, he whistled and bawled to his dogs, and with a jolly smirk and flourish of his cocked-hat, off he went to seek other adventures.

Thus, was there feud and malice between two houses, and Aunt Rebecca's wrong-headed freak of cutting the Macnamaras (for it was not 'snobbery,' and she would talk for hours on band-days publicly and familiarly with scrubby little Mrs. Toole), involved her innocent relations in scorn and ill-will; for this sort of offence, like Chinese treason, is not visited on the arch offender only, but according to a scale of consanguinity, upon his kith and kin. The criminal is minced—his sons lashed—his nephews reduced to cutlets—his cousins to joints—and so on—none of the family quite escapes; and seeing the bitter reprisals provoked by this kind of uncharity, fiercer and more enduring by much than any begotten of more tangible wrongs, Christian people who pray, 'lead us not into temptation,' and repeat 'blessed are the peace-makers,' will, on the whole, do wisely to forbear practising it.

As handsome, slender Captain Devereux, with his dark face, and great, strange, earnest eyes, and that look of intelligence so racy and peculiar, that gave him a sort of enigmatical interest, stepped into the fair-green, the dark blue glance of poor Nan Glynn, of Palmerstown, from under her red Sunday riding-hood, followed the tall, dashing, graceful apparition with a stolen glance of wild loyalty and admiration. Poor Nan! with thy fun and thy rascalities, thy strong affections and thy fatal gift of beauty, where does thy head rest now?

Handsome Captain Devereux!—Gipsy Devereux, as they called him for his clear dark complexion—was talking a few minutes later to Lilias Walsingham. Oh, pretty Lilias—oh, true lady—I never saw the pleasant crayon sketch that my mother used to speak of, but the tradition of thee has come to me—so bright and tender, with its rose and violet tints, and merry, melancholy dimples, that I see thee now, as then, with the dew of thy youth still on thee, and sigh as I look, as if on a lost, early love of mine.

'I'm out of conceit with myself,' he said; 'I'm so idle and useless; I wish that were all—I wish myself better, but I'm such a weak coxcomb—a father-confessor might keep me nearer to my duty—some one to scold and exhort me. Perhaps if some charitable lady would take me in hand, something might be made of me still.'

There was a vein of seriousness in this reverie which amused the young lady; for she had never heard anything worse of him—very young ladies seldom do hear the worst—than that he had played once or twice rather high.

'Shall I ask Gertrude Chattesworth to speak to her Aunt Rebecca?' said Lilias slyly. 'Suppose you attend her school in Martin's Row, with "better late than never" over her chimneypiece: there are two pupils of your own sex, you know, and you might sit on the bench with poor Potts and good old Doolan.'

'Thank you. Miss Lilias,' he answered, with a bow and a little laugh, as it seemed just the least bit in the world piqued; 'I know she would do it zealously; but neither so well nor so wisely as others might; I wish I dare askyouto lecture me.'

'I!' said that young lady. 'Oh, yes, I forgot,' she went on merrily,' five years ago, when I was a little girl, you once called me Dr. Walsingham's curate, I was so grave—do you remember?'

She did not know how much obliged Devereux was to her for remembering that poor little joke, and how much the handsome lieutenant would have given, at that instant, to kiss the hand of the grave little girl of five years ago.

'I was a more impudent fellow then,' he said, 'than I am now; won't you forget my old impertinences, and allow me to make atonement, and be your—yourveryhumble servant now?'

She laughed. 'Not my servant—but you know I can't help you being my parishioner.'

'And as such surely I may plead an humble right to your counsels and reproof. Yes, youshalllecture me—I'll bear it from none butyou, and the more you do it, the happier, at least, you make me,' he said.