Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

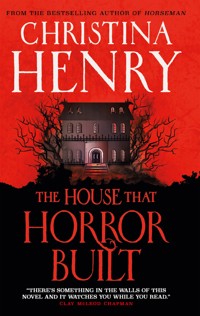

A woman working in the house of a reclusive horror director stumbles upon terrifying secrets, from the author of Good Girls Don't Die and Horseman. Single mom Harry Adams has always loved horror movies, so when she's offered a job cleaning for revered horror director Javier Castillo, she leaps at the chance. His forbidding Chicago mansion, Bright Horses, is filled from top to bottom with terrifying props and costumes, as well as glittering awards from his decades-long career making films that thrilled audiences and dominated the box office—until family tragedy and scandal forced him to vanish from the industry. Javier values discretion, so Harry tries to clean the house immaculately and keep her head down—she needs the money from this job to support her son. But then she starts hearing noises from behind a locked door. Noises that sound remarkably like a human voice calling for help, though Javier lives alone and never has visitors. Harry knows that not asking questions is a vital part of keeping her job, but she soon finds that the house—and her enigmatic boss—have secrets she can't ignore…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Harry: before

Chapter One

Javier Castillo: before

Chapter Two

Harry: before

Chapter Three

Javier Castillo: before

Chapter Four

Harry: before

Chapter Five

Javier Castillo: before

Chapter Six

Harry: before

Chapter Seven

Javier Castillo: before

Chapter Eight

Harry: before

Chapter Nine

Javier Castillo: before

Chapter Ten

Harry: before

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

About the Author

praise for christina henry

“After reading The House that Horror Built, I brought the terror into my own home and now it won’t leave. Christina Henry has me questioning every creak, every warping floorboard, every stray sound around my house and now I can’t sleep at night. There’s something in the walls of this novel and it watches you while you read.”

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN

“A delicious exploration into the monsters we idolize and the monsters we create. The House that Horror Built will leave readers wondering what lies behind the mask of their beloved horror auteurs.”

CARISSA ORLANDO

“A true page-turner.”

PAUL TREMBLAY

“Hair-raising, heart-stopping suspense from start to finish. A perfect nightmare of a novel.”

RACHEL HARRISON

“For years now Christina Henry has been showing us the cracks in the world, and the magic passing through. Now she leads us not to a large crack, but to four hairline tears. I followed her down each of them, and I got lost, and wished I’d never find my way back.”

FRANCESCO DIMITRI

“Henry’s storytelling is her own sort of witchcraft.”

CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN

“Full of magic and passion and courage, set against a convincing historical backdrop… Henry’s spare, muscular prose is a delight.”

LOUISA MORGAN

“Henry has mastered the art in Looking Glass, linking together four stories that expand and deepen the brutal and vibrant world she’s created. Alice and Hatcher and Elizabeth’s stories are the fairy tale of survival and transformation that every grown woman needs.”

A. J. HACKWITH

“Hugely creepy and brilliantly inventive.”

HEAT

Also by Christina Henry and available from Titan Books

ALICE

RED QUEEN

LOOKING GLASS

LOST BOY

THE MERMAID

THE GIRL IN RED

THE GHOST TREE

NEAR THE BONE

HORSEMAN

GOOD GIRLS DON’T DIE

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The House that Horror Built

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364032

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781835411612

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364049

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: May 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © Christina Henry 2024.

Published by arrangement with Berkley, an imprint of Penguin

Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Christina Henry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Henry, who is only just beginning

Imagination, of course, can open any door—turn the key and let terror walk right in.

—Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

HARRY

before

SHE REMEMBERED FALLING IN love with movies when she was very young, remembered disappearing into the dark with only the flickering screen to guide her. She remembered the feeling of drifting away from the seat and the small bag of too-salty popcorn and into the movie as the restless sounds of her mother and father and sister shifting and coughing and whispering faded to another time and place, another time and place that Harry had left behind.

Her parents took her to very few films, and even then only films that were considered “clean”—while the rest of her fourth-grade class chattered excitedly about Titanic she had to content herself with occasional glimpses of clips seen during television commercial breaks. Her parents were half-convinced that film and television were actual tools of the devil, and Harry and her sister Margaret (always Margaret, never Maggie) weren’t allowed to see anything that had higher than a G rating. But Harry didn’t care. She loved the movies—loved the drive to the theater and the way everything smelled like hot butter and Raisinets, loved watching the coming attractions before the film started and the hush of anticipation that fell when the title sequence began. Even if she was only allowed to see G movies at least she was seeing movies. At least she was someplace besides her sober, judgmental household, a place where the only acceptable conversation was prayer and the only acceptable attitude was piety.

Harry knew her family was different than other families, even different from most of the families who attended the same church. Her school friends attended Sunday school with her and went to Christian summer camp, but they also were allowed to walk the mall in small groups. They had cable television and saw rated R movies late at night after their parents had gone to bed. They had new clothes from places like the Gap and American Eagle and Aeropostale, while Harry and Margaret were only allowed Salvation Army secondhands.

Harry was eleven when she was permitted to attend her first sleepover birthday party. She’d begged her mother to allow her to go, having always been the only girl left out when she had to turn down previous invitations. For some reason, on that particular occasion, her normally stern mother relented—a decision she would likely regret for the rest of her life, because it was on that night that Harry was irredeemably corrupted.

The friend, Jessica Piniansky, had an older sister named Erin who had been left in charge of the menagerie of girls for the evening while Jessica’s parents wisely went out to dinner after the birthday cake was served. Erin had been dispatched to the local video store to rent Kiefer Sutherland movies, as Kiefer was Jessica’s current obsession and her bedroom was plastered with photographs of him torn from Us and Entertainment Weekly and People that she’d taken from the library. Jessica always had slightly out-of-date obsessions, like she ought to have been born ten years earlier.

Erin had returned with copies of The Lost Boys and Flatliners, two films that Harry would never have been permitted to watch under normal circumstances. Her hands were sweaty as The LostBoys slid into the DVD player, as she stared down the barrel of doing something her parents would not approve of.

All around her the other girls argued over the relative merits of Jason Patric vs. Corey Haim vs. Kiefer Sutherland, but Harry didn’t join in. She was in love with the dark, with the lost boys swinging and flying under the railroad track, with the arterial spray of the first vampire attack, with the blood gushing from the sinks and spattering all over the house. She relished the thrumming of her heart, the pulse of her own blood, the terror and the splendor and the excitement she’d never felt before.

When the movie was over she felt reborn, reborn as an addict seeking another thrill. She didn’t know how she would find it again, how such a visceral pleasure would ever be allowed in a home where pleasure of any kind was a sin.

She began to sneakily read copies of Fangoria magazine whenever she saw them—at the corner store when she was sent out to buy milk, or at the bookstore when her mother wasn’t paying attention. As she entered high school and she got a job of her own—making ice cream cones and sundaes at Dairy Queen after school—she had more time and money to do what she liked, to stop and buy those copies of Fangoria on the way home and ferret them away between her mattress and box spring, taking them out only when everyone else in the house was asleep and scanning the pages, flashlight in hand, seeing hints of worlds where she still wasn’t permitted to travel—places where regular people were flesh-eating cannibals, or writers accidentally opened portals to terrible universes, or alien creatures stalked a prison world. She wanted more. She always wanted more, and more, and more, but it wasn’t until she made her escape—when she became Harry Adams and left Harriet Anne Schorr behind forever—that she could have all the terror she wanted, and then some.

CHAPTER ONE

IT WAS THE SIZE of the house that got Harry every time she saw it. Of course she’d seen houses that size before, in Certain Neighborhoods around Chicago, giant houses whose sheer enormity should have relegated them to the suburbs. This city house wasn’t a McMansion, though—one of those classless boxes, bulging oversized dwellings for those who wanted to display their money, or at least their debt.

It was decidedly not new, not the province of some futures broker or investment banker. It had the same greystone face as her own two-flat apartment building—a fifteen-minute bus ride and half a world away, economically speaking—but it was twice the size. The house covered two lots, with a third lot for a side yard. As an apartment dweller she didn’t often contemplate property taxes, but just the fact of those three lots made queasy multi-digit numbers dance before her eyes.

The building was three stories plus a basement level. The windows were tall on the lowest story, less so on the second one, and downright tiny on the topmost, giving the overall effect of slowly closing eyes if you glanced from the bottom to the top.

Other than the oddly sized windows there were no particular architectural flourishes save two. At the northeast corner of the roof a sculpture protruded like a Notre Dame gargoyle—a horse’s head and neck carved in stone, the horse’s lips pulled back, its eyes wild. All around the horse, stone flames rose, waiting to burn. Harry thought she’d grimace, too, if she was trapped in fire for all eternity.

In addition to the frantic stallion, there was a name carved in an arc above the door—BRIGHT HORSES.

The entire property was surrounded by a ten-foot-high black iron fence. The only two entry points were the gate in front of her and the sliding gate in front of the garage in the back.

Harry reached toward the call box so she could be buzzed in, but paused as she heard her phone chirp in her pocket. She pulled it out and saw a text from her son, Gabe.

FORGOT MY CHEM REPORT! IT’S ON MY DESK? followed by a praying hands emoji.

Already at work, she texted back, and tacked on the woman shrugging and holding her hands up.

She only worked three days a week, so if Gabe had tried on a different day she might have hopped the bus and brought his report to him. Maybe. Part of her thought he needed to learn the consequences of not thinking ahead and putting the report in his bag the night before. The other part of her wanted to cut him some slack, given that it was his freshman year and the first time the kids were back at school post-pandemic, even if it was only three days a week.

She was grateful that it was only two days off in-person schooling, as her unemployed spring (furloughed from her server job, never to return) coupled with overseeing remote learning for a thirteen-year-old with ADHD had resulted in screaming, emotional breakdowns for both of them. Having Gabe’s learning monitored by qualified teachers was a profound relief.

Harry watched the reply bubbles churn on her screen until Gabe’s answer popped up. A sad face emoji, followed by a shrugging boy.

Noise crackled from the call box and a deep baritone voice emitted from it. “Are you going to stand there all day, or perhaps you’d like to work?”

Harry glanced up at the camera perched on the top corner of the fence. The preponderance of cameras in and around the house always left her feeling uneasy, even though she understood the necessity of them. There were a few too many, in Harry’s opinion, though she was careful to keep that opinion to herself.

“Sorry, Mr. Castillo,” she said, and the gate buzzed.

Harry pushed the gate open and hurried up the walk as Javier Castillo opened the front door, watching her approach.

“We’ll start in the blue room today,” he said as she jogged up the steps.

“No problem,” she said, pausing in the doorway. She pulled her slippers—plain gray terry cloth scuffs, bought expressly for and used only at the Castillo residence—out of her backpack, placed them on the floor in the entryway and toed out of her sneakers one by one, sliding each foot into a slipper without ever touching the ground.

Harry picked up her sneakers and carried them inside, placing them on the special shelf to the left of the doorway. No outside dirt, damp or germs touched the floors in Bright Horses.

The shelf that housed her sneakers was something like a preschooler’s cubby, with a space for shoes at the bottom, hooks for bags and coats in the center, and a top shelf for hats and other items. Harry pulled off her black windbreaker and hung it on a hook. She slid her cell phone into her backpack as Mr. Castillo watched. There was a strict no-phone policy inside the house. Violation of this rule was grounds for immediate dismissal, though she was allowed to go outside during her lunch break to check messages.

Mr. Castillo held out the box of latex gloves stored on a side table behind the door. Harry pulled on the gloves, wincing a little as she did. She hated the feeling of pulling on the gloves, the way the material seemed to grab and yank at her skin. Once the gloves were actually on she didn’t mind them as much, although she still liked the moment at the end of the day when she was allowed to peel them off and let her skin breathe again.

Harry adjusted her medical mask—Mr. Castillo never allowed her to remove it inside the house except in the kitchen when eating or drinking—so that all that was visible were her faded blue eyes and the bit of her forehead that showed when she pulled her pin-straight blond hair into a ponytail. She followed him down the hallway and up the stairs to the second floor.

The entry to the house was deliberately neutral—the plain gray carpet and faded wallpaper practically screamed, There’s nothing to see here! But upon leaving the downstairs hall and passing into any other room the true nature of Bright Horses was revealed.

It started on the stairway, after the first few steps, when the stairs curved to the left, out of sight from anyone standing in the entryway. A large framed poster of a voluptuous blonde in a red dress hung on the wall there. A snarling cat, blood dripping from its mouth, curled over her right shoulder, and over her left were the words SHE WAS MARKED WITH THE CURSE OF THOSE WHO SLINK AND COURT AND KILL BY NIGHT! Above her head the words CAT PEOPLE floated over a clock whose hands showed midnight.

Harry always smiled at this poster, as Cat People was one of her favorite films, though Mr. Castillo had hastened to point out that the poster wasn’t an original print. Most of the posters that lined the wall along the stairs were contemporary copies, though there were a few genuine articles—the original U.K. quad poster for Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein, the lurid red French theatrical poster for Eyes Without a Face, a U.S. lobby poster for An American Werewolf in London.

It was slow going to the top of the stairs, as Mr. Castillo always got out of breath halfway up and had to stop. Harry didn’t remark on this, or offer any help. She’d made the mistake of offering assistance once, saying she would fetch a glass of water.

“I’m fine,” Mr. Castillo snapped. “I’m just fat.”

Harry attributed his breathlessness to lack of regular exercise rather than size—she knew plenty of heavier people who had no trouble with stairs because they ran or lifted weights on the regular, and plenty of thin people who tired after walking half a block. But she hadn’t said this.

She hadn’t said anything unnecessary or even vaguely personal, because it had been her first day. She was grateful to have work again, and desperately averse to jeopardizing her new source of income.

Even now, more than a month later, she never said anything that might be construed as personal. She was too much in awe of him, in awe of this person who’d let her into his home.

Javier Castillo had brown hair going gray, brown eyes behind steel-rimmed spectacles, was on the shorter side (though not as short as Harry, who had reached five feet at age thirteen and never grown again) and overall had the completely nondescript appearance of any random person on the block. He was the sort who would never attract attention unless you knew who he was, would never be whispered about if he went to the grocery store—which he never did. He never went anywhere if he could help it.

Because of this, very few people in his neighborhood realized one of the world’s greatest living horror directors lived among them: Javier Castillo, director and writer of fifteen films, most of them visually groundbreaking, genre-defying masterpieces. His film The Monster had won the Oscar for Best Picture five years earlier and swept most of the other major categories along the way, including Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. The world had waited breathlessly for the announcement of his next project.

Then a shocking, unthinkable incident happened, and Castillo withdrew into his California home, and there was no mention of potential new movies while the paparazzi stood outside his house with their cameras ready for any sign of life within.

After one too many wildfires came too close to his residence he decided to move, somewhat incongruously, to Chicago. He packed up his legendary and possibly priceless collection of movie props and memorabilia and brought them to a cold Midwestern city where the last major urban burning was decidedly in the distant past.

If it wasn’t for those California wildfires Harry would still be collecting unemployment, frantically responding to job ads with a horde of other desperate people, never hearing back, wondering how long Gabe would believe her tight smile followed by, “Everything’s going to be fine.”

But instead there was this miracle, this miracle of a strange and reclusive director who needed someone to help him clean his collection of weird stuff three days a week, and so Harry climbed up the stairs and listened to Javier Castillo huff and puff.

The second floor was essentially one big room divided by a load-bearing archway. The stairs curved up to the southwest corner of this room and stopped there. The stair to the third floor was on the northeast corner, which always made Harry think of a Clue board, with its seemingly random staircases scattered all around. There was a black railing running along from the southeast corner of the room to the top of the stairs to keep people from falling straight down the first-floor stairwell.

The bucket of cleaning supplies was ready at the top of the stairs. Harry and Mr. Castillo each took a long-handled duster. Mr. Castillo went to the far end of the room while Harry started on the closest figure.

The blue room wasn’t entirely blue. The carpet was blue—and Harry really thought he ought to get rid of the carpet; it collected dust and it was such a difficult room to vacuum. The wallpaper had blue flowers patterned on it, blue flowers that made Harry think of Agatha Christie’s story “The Blue Geranium.”

Except that’s not quite right, Harry thought. In “The Blue Geranium” the color of the flower on the wall changed to blue because of a chemical in the air—proof of poison.

Nobody was in danger of poisoning in Bright Horses. Nobody lived there except Mr. Castillo—and his props, of course, and some of those were so lifelike that Harry sometimes thought they really were watching her, just out of the corner of her eye. When she’d turn, the figures would be still and glassy-eyed, the artificial pupils staring off into the middle distance, never having focused on her or anything else at all.

Harry loved most of the films that the props came from, but despite this the blue room, in particular, gave her a creepy-crawly itch on the back of her neck. She didn’t know why. She knew the props were make-believe, knew they were just elements of the movie magic that she loved so much. But the feeling still persisted—a feeling of something not quite right.

All the various members of the collection were posed on skeleton-like frames, so that the overall result was a museum diorama grouped according to some internal catalog system of Mr. Castillo’s devising.

Harry dusted a Xenomorph puppet from Alien3. The creature’s jaw extended from the head as if it was about to bite. Harry liked the Alien movies. She was a fan of most of the source material for the props littered around Bright Horses. But she’d discovered, to her surprise, that she didn’t like the pieces separated from their performers, didn’t see the appeal of latex and foam rubber without animation. Devoid of both life and context, the costumes were nothing but shed snakeskin, a pantomime of their original intent.

Harry moved from the Xenomorph to a figure that had been featured in one of Mr. Castillo’s films, a kind of half-goat/half-demon hybrid. In the film, A Messenger from Hell, the creature, Sten, had acted as a sort of sinister guardian to the main character, Flora. It was one of Harry’s favorite movies, a transcendently beautiful piece of art that was also deeply grotesque—in other words, a Castillo film.

But the first time she was confronted with the mask and costume she found herself deeply, viscerally repulsed, barely able to look at it and unable to explain why.

As Harry fluttered the duster over the face she caught, as she always did, the faint odor of sweat and talcum powder. She’d thought, on the first occasion, that this was simply the scent of the actor who’d worn the mask, lingering inside the rubber. But then she realized that was absurd, that all these pieces were specially cleaned and treated before Mr. Castillo displayed them. Of course it didn’t still smell like the actor.

Still, every time Harry dusted the sharp distended chin, the high cheekbones, the pointed ears, the curling horns, she was certain that the fanged mouth would curl up in a terrible smile, that the icy blue eyes would shift in her direction a moment before long-fingered hands grasped her shoulders. And every time she felt this way she shook off her unease, recognizing it as irrational. She loved the character in the movie, and a costume and mask were just that—empty props. They were nothing to be frightened of.

On a deep level, though, she recognized that this half belief—or maybe willingness to believe—that the mask would come to life was one of the reasons why she loved horror movies so much. She never saw the props and the fake blood and the clear unreality of it all. She was perfectly credulous, always, perfectly willing to believe in what the filmmakers put on-screen. Harry never held herself away from what she viewed. She was a part of it.

Harry moved on to brush the elaborate folds of the silken costume, absolutely positive that the head was tilted down, watching her as she worked, and just as equally certain that the idea was absurd.

She was thirty-four years old, well past the point in life when she was allowed to be scared of inanimate objects. Still, it was a relief, as always, to move away from the figure to the other costumes behind it, to feel the pressure of that terrible gaze lift.

A number of the figures on this side of the room were also from Mr. Castillo’s own films—a massive demon, red-skinned and black-clawed; an eyeless troll, the folds of its body the same texture as elephant skin; a tiny, gauzy-winged fairy with terribly sharp teeth.

Harry knew all the movies the props came from, loved some of them enough to have watched and rewatched over and over. She never mentioned this. She had sensed during the interview that gushing fandom would be a detriment to her job prospects, and Harry really needed the job. Her unemployment check had barely covered the rent, even though she had one of the few affordable apartments in a neighborhood that had progressed rapidly from “gentrifying” to “upwardly mobile.”

Harry had been one of the few parents in Gabe’s elementary school whose income didn’t remotely approach six figures, which led to increasing embarrassment as the years passed and the financial expectations grew.

First it had been “fundraising” for full-day kindergarten (the state only paid for a half day) with an “expected donation” of “$2,000 per family.” It was a public school, and Harry had never had two thousand dollars in one place in her entire life, so she’d shrugged and said she couldn’t pay, and that was that.

She hadn’t minded the idea of Gabe in half-day kindergarten anyway, as she possessed the apparently radical notion that five-year-olds should spend more time running around than drilling reading skills.

Harry had mentioned this to another mom once (full-day kindergarten having been fully funded despite Harry’s lack of contribution) and the other parent had given Harry the kind of look normally reserved for serial killers or politicians she disagreed with.

“It’s absolutely vital that young kids get a head start on learning. Statistics show that full-day kindergarten is a predictor of future success,” the mom had said.

Or a predictor of future burnout, Harry had thought as the woman continued to lecture. Harry had nodded and privately vowed never to mention her personal opinion on anything school-related ever again.

As the years passed there had been one expectation after another—the yearly gala, for which the wealthy and well-connected donated things like Cubs tickets and spa days and wine country vacations for auction. Harry never had anything to donate or any money to bid, so she always gave vague answers when asked about the gala and made sure she had something else to do that night—and usually she did, because unlike almost every other mom at pickup she sometimes had to work evenings.

Then there was an “expected donation” of “$200 per family” per year, used toward arts and theater programs. Harry tried to scrape this up every year, carefully saving a portion of her summer tips, since she believed school should be about more than just math. Still, there always seemed to be some new thing to contribute to—the walk-a-thon, the science lab, the ticket money for the yearly musical.

Harry had moved to the neighborhood because it had one of the best K–8 schools in the city, and entry was only guaranteed for residents. But the constant flood of financial requests had drained her, and the additional expectation that she had the time or the energy to volunteer in various capacities had been equally frustrating.

She worked during school hours, unlike most of the Lulu-lemon moms of Gabe’s classmates—women who wore Canada Goose jackets in winter and expensive blonde highlights year-round, women who drove Lexus SUVs and spent their children’s school hours taking barre classes and chatting with other moms at Starbucks. It had been hard for Harry not to resent these women and their clueless privilege. But Harry had gritted her teeth and stuck it out so that Gabe could have a better chance at one of the top high schools in the city.

She’d worked—before the pandemic, before everything came crashing down—at an upscale-ish restaurant only a couple of blocks from her apartment, a place where many of those school moms with unlimited leisure time lunched during the school week. They always gave her fake smiles while ordering their grilled chicken salads, but they left nice tips (probably worried that Harry would tell the other moms that they were cheap otherwise), so Harry fake-smiled them right back and thought about Gabe.

Gabe. The best kid in the world. She knew every mother thought that about her kids but in Gabe’s case she was firmly convinced it was true. Whenever Harry looked at Gabe she felt a fierce, almost incomprehensible love inside her, a love that was sometimes painful in its intensity. She was a bottle filled with hopes and dreams for him, tempered only by free-form anxiety that Something Might Happen to her only, most beloved child—COVID, cancer, a bus accident, a school shooting.

She never expressed these fears except to sometimes give Gabe an extra-long hug before he left for school, which he patiently tolerated for a few moments before saying, “Okay, Mom.” That was her cue to release him, and she would, hiding the sudden emptiness she felt with an off hand “Be safe and learn stuff, okay, kiddo?” He would duck his head and grin and leave, and she’d fight the urge to call him back, to keep him home where the world couldn’t harm him.

Mr. Castillo’s voice broke into her reverie. “I have several calls to make, so as soon as we’re finished here you can go upstairs. After lunch we will tackle the first-floor and basement rooms.”

Mr. Castillo was always present whenever Harry cleaned one of the prop rooms, and in fact he did half the work, lovingly caring for his masks and costumes and maquettes. Harry’s sole purpose was to assist, for he couldn’t keep everything clean on his own. But the “regular” rooms—rooms without film collectibles, of which there were very few—were Harry’s responsibility.

These included three bedrooms upstairs—Mr. Castillo’s room and two guest rooms—the bathrooms on the first and third floors, the kitchen, and what Mr. Castillo referred to as “the small library.”

The small library was essentially a reading room on the third floor, a place for him to store paperbacks that had no special monetary value. It was Harry’s favorite room in the house, much nicer than the formal library downstairs. There were shelves stuffed with books stacked every which way, following no particular organizational system, and two big soft armchairs, each with its own side table and reading lamp.

Her second-favorite room was downstairs off the dining room. Mr. Castillo called it “the screening room.” There was a large movie screen at one end, maybe eight feet across, and about twenty extremely comfortable chairs in rows to watch movies. He had even added a little mobile popcorn cart in the corner.

It was the sort of room Harry had always wanted in her own place, except they lived in a two-bedroom apartment and there was no extra space for a broom closet, never mind anything as extravagant as a reading room or a special room to watch films.

Someday, she told herself, but deep down she knew she’d been saying “someday” for ten years or more and that someday might never come.

Especially not if you keep working as a house cleaner, she thought as she ran the vacuum carefully around the blue room under Mr. Castillo’s watchful eye. She was grateful for the job, for the money, but it was not exactly a path to wealth or even the stability of the middle class. It just meant she worried about money every five minutes instead of every single second.

As soon as she was finished vacuuming she rewrapped the cord around the machine and carried it to the upstairs hallway before returning to the blue room for the rest of the cleaning supplies. Mr. Castillo had already left to make his calls from his downstairs office.

He often did this, disappearing without a word and reappearing suddenly, always silent, like he was expecting to catch her goofing off or thought that he might discover the existence of a second, secret cell phone being used to take photographs. Harry tried not to be offended by the unspoken implications. Mr. Castillo wasn’t unkind—a little on the stern side, perhaps, but he was fiercely protective of his privacy. She was there to do a job and he wanted her to do it and leave, not poke around in his things or stare out a window.

Harry understood that. Really, she did. So she tried not to feel offended by his monitoring, and mostly she succeeded, and if resentment stuck in her craw she just swallowed it down. Resentment is a familiar meal when you can’t afford contentment.

Harry went into the first guest room on the right on the third floor. There wasn’t much to do in there, just run a duster over the furniture and vacuum the carpet. Once a week she changed the sheets and shook out the duvet. It seemed a ridiculous waste of effort and washing water to keep the guest room beds fresh and ready for anyone arriving at a moment’s notice, particularly when Mr. Castillo never even appeared to invite anyone over for dinner. Harry considered it would be much more practical to wrap the mattress in plastic until it was needed, but it was not her house, nor was it her place to make suggestions.

She finished the first room and moved down the hall to the next guest room on the right. As she ran the duster over the dresser a soft thump sounded from the far wall, seemingly coming from the room next door.

Harry had expected this noise, so she didn’t jump the way she had the first several times it happened, nor did she attempt to investigate its source. She hummed a little tune, the way a child might whistle in the dark to keep the monsters away.

She first heard the noise maybe two weeks after she’d started working for Mr. Castillo, and it had recurred intermittently since then.

The thump came again, louder than before, but her breath and her tone remained even as she kept humming.

The noise sounded once again, and she thought, not for the first time, It sounds like someone kicking the wall.

But no one lived at Bright Horses except Mr. Castillo, so it couldn’t be someone kicking the wall. Likely it was just an oddity in the pipes—the old heating systems in a lot of houses made noises like that.

As she exited the second guest room and crossed the hall to the small library she kept her eyes averted from the closed door to her right, the last room on the guest room side.

That door was always locked, and it wasn’t her job to be curious about it.

JAVIER CASTILLO

before

IN 1970, WHEN HE was eight years old, his mother dropped Javier and his brother Luis off at the cinema so she could shop for a couple of hours without dealing with their constant bickering. They loved each other, the way that brothers do, but they also loved needling each other, the way that brothers do.

There was visible relief in her eyes as she called to them, “Have fun, be careful,” but Javier barely noticed. He was already thinking of hot buttered popcorn slipping between his fingers, the click of the projector, the curtains parting to reveal the white screen in the moments before it filled with giant monsters.

Luis was four years older than Javier and loved Godzilla movies, or anything close to a Godzilla movie (he’d take a Gamera film in a pinch, though he didn’t prefer the giant turtle, who was a little too cute for Luis’s taste). Fortunately for Luis, the owner of the Majestic Theater also loved Godzilla movies, and that meant they were going to see Destroy All Monsters.

Javier didn’t remember the exact plot of the movie later, when their mother (bearing a fresh manicure and fewer lines in her forehead) picked them up and bore them home. He only remembered the monsters—Rodan, the flying dinosaur who moved at great speeds; Mothra, the giant caterpillar who could become a magical butterfly; Manda, an enormous sea dragon with an incredibly long neck; Anguirus, who looked like a cross between a dinosaur and a turtle and a roly-poly bug, and who always made Javier laugh.

Of course, his number-one monster was Godzilla, the king of them all—Godzilla with his deliberate, destructive walk and the terrible flash of his nuclear breath. Godzilla, who was feared by everyone but also loved—what a strange thought this was for young Javier. If he ever saw Godzilla in real life, he didn’t know if he would cheer or run screaming.

In the movies, people always did a little bit of both. Maybe that was how monsters were supposed to make you feel. Maybe they were supposed to make your heart thrill and your blood run cold at the same time. Maybe they made you want to run and to stay, to escape but always to look back because you had to see.

And the exhilaration of Monster Island—a place just for giant monsters to live! Javier dreamt of this island at night, dreamt of being allowed to live there, to wake each morning in a tent on the beach and see Minilla laughing and blowing smoke bubbles instead of fiery breath like his great father.

As he grew older, all he wanted was to live among monsters, to make their monstrosity a part of him, to feel that he too was terrible and beautiful, that perhaps even when others wanted to run from him they would stand and stare, and be unable to look away.

CHAPTER TWO

GABE WAS AT THE dining room table with his homework spread out before him when Harry got home. He was tall and gangly like his father, all long limbs and sharp joints, and his legs stuck out in front of him. He had dark curly hair the exact opposite of her own and he wore it shaggy, which was apparently the fashion now. He was just starting to get a little hair above his upper lip, that wispy-nothing of a mustache that most boys in their early teens have.

His head and shoulders hunched over an open workbook, and as Harry dropped a kiss on the back of his head she saw his left hand carefully writing out solutions to algebra problems that appeared frighteningly incomprehensible to her. Harry was relieved Gabe had an aptitude for math, since it had been her worst subject and she wouldn’t be able to help him with it if she tried.

“There’s a letter from Mr. Howell for you,” Gabe said, not looking up. “He was leaving when I was coming in and he gave it to me.”

Harry frowned. Ted Howell Jr. was the son of the original owner of the building. Howell Sr. had always kept the rent in the building artificially low, which had allowed Harry and Gabe to stay in one place for more than ten years.

The apartment above theirs had been host to a rotating wheel of tenants who stayed, on average, two years before moving on. Their current neighbors were two twentysomething girls who both worked office-jobs-gone-remote since the pandemic. They were nice enough, if a little bland. They didn’t make a lot of noise, though—that was the important thing.

Harry and Gabe had once spent a nightmarish year with a couple of party-all-the-time college boys living upstairs. Harry remembered feeling constantly snappish and irritable, never able to get a decent night’s sleep because the neighbors always decided the exact right time to turn on their music to soul-crushing volume was eleven p.m. or later.

Howell Sr. had informed Harry about six months previous that he was handing over administration of his business—he owned three apartment buildings in the neighborhood—to his son. Ever since, Harry had felt a continuous, low-frequency dread that Howell Jr. would raise the rent to something more in line with the rest of the neighborhood and they would be forced out.

It wasn’t so essential that Harry and Gabe stay in this neighborhood now that Gabe was out of elementary school; it was simply that Harry was completely unable to manage the cost of a move at the moment. Her “savings account” (she always thought of it in air quotes, since no matter how hard she tried she never managed to get ahead of her expenses long enough to do any significant saving) was completely depleted by the long months without work. She couldn’t afford to pay a security deposit and first month’s rent plus the current rent on her new place, never mind the cost of a moving truck.

Gabe had left the envelope from Ted Howell on the counter next to the mail. Harry’s hand hovered over the envelope, trying to decide if it was better to rip the bandage off right away or to wait until later, when she was alone.

As a single mother she was always deeply conscious of how easy it would be to burden Gabe with adult concerns that weren’t his to bear. It would be easy to complain to her son about her worries, to make him the second adult in the house when that role should be filled by a partner, not a child.

It had been just Harry and Gabe since he was born, the two of them against the world. But it wasn’t his responsibility to worry about the rent or food or doctor’s appointments. His job was to go to school and play video games and mess around with his friends, to make mistakes, to get in trouble, to learn, to grow up to be a better adult than she was herself.

She’d wait until later to read Howell’s note. In fact, she thought as she separated the junk mail from the first class and saw that all that remained was bills, I’ll just save all the bad news for after Gabe has gone to bed.

A thump came from above her head, the sound of one of her neighbors dropping an object on the hardwood floor. Harry started, and Gabe laughed.

“Jumpy much, Mom?”

Normally she’d laugh and make some sarcastic comment back, but she found it was caught in her throat. The noise sounded exactly like the one that had come from the other side of the wall in Mr. Castillo’s second bedroom. The sounds happened every time she went in there, usually intermittently. That day the noise had been consistent and determined, so much so that for a moment she thought someone was trapped in the room.

That’s ridiculous, she thought. One of the most prominent filmmakers in the world has not imprisoned someone in his spare room. Probably.

(What if someone is trapped in there and you’re ignoring it and you could save them? What if it’s like that movie with Catherine Keener that was based on a true story—the one where she kept the girl in her basement and tortured her and nobody did anything about it?)

“What’s that movie, that true-crime movie about the mom who kept the girl in the basement?” Harry asked as she rummaged in the cupboards, trying to decide what to cook for dinner.

“Are you trying to tell me something? Should I be worried if I come home with an F?” Gabe said.

“I can’t imagine you failing anything.”

“You never know. It could happen.”

Something in his tone made Harry stop rummaging and look at Gabe. “Are you trying to tell me something?”

His shoulders hunched in more and he continued scrawling answers to his algebra work as he said, “No. I’m just saying it could happen. High school is a lot harder than eighth grade.”

Harry stared. Was Gabe struggling? Was a teacher giving him a hard time? Maybe she should have asked Mr. Castillo if she could run Gabe’s missing report up to school that morning after all. Did he need extra help? Should she arrange for a tutor?

“If you’re struggling—”

“I’m not. I’m not. Don’t start that panic spiral thing you do.”

Harry frowned. “What panic spiral thing?”

“That thing where you start imagining every possible permutation of doom, and you just sit there getting more and more worked up behind your eyes and you think I don’t notice.”

“I don’t do that,” Harry said. She did do that, but she’d thought—or rather, hoped—he hadn’t noticed.

“Yeah, you do,” Gabe said.

“No, I don’t.”

“You do.”

They glared at each other for a moment, and Harry really noticed for the first time how much older he looked. There was an adult lurking behind Gabe’s eyes, and she felt a pang of preemptive loss, like a memory she didn’t have yet.

Gabe dropped his eyes first. Harry opened her mouth, not sure what she intended to say, but then Gabe spoke.

“An American Crime.”

“What?” Harry said. She was wrong-footed, lost in a different thread of conversation.

“An American Crime. That’s the Catherine Keener movie you were talking about before.”

“Oh. Right.”

She felt disoriented, which always made her grumpy, but she didn’t want to take it out on Gabe, so she pulled a box of spaghetti out of the cabinet and began filling a pot with water.

“Did you like my use of the word ‘permutation’?”

“Huh?”

“When I said ‘permutation of doom.’ I thought that was pretty good.”

She shut off the water and found him grinning at her, and she grinned back. Something clenched tight inside her eased then, and the slightly out-of-sync feeling she’d had all day cleared up.

“New vocabulary word?” she asked.

“Yup,” he said. “Probably the only one I’ll remember.”

“Guess you’d better study your vocabulary words then,” she said.

Her eyes found the envelope from Howell Jr., but she turned away from it, wanting to keep the anxiety away for a little longer.

Later. Later, when Gabe won’t see.

* * *

“ARE YOU FEELING WELL?” Mr. Castillo asked.

“Hm?” Harry asked, her brain one million miles from her current location.

“Are you feeling well?” he repeated. “You seem very distracted today. I thought you might be unwell.”

Harry was sure she did a terrible job keeping the shock off her face. Mr. Castillo had never before appeared to notice her mood, or even notice her beyond her value as a human dust remover.

He frowned at her now, his own duster in hand, his slightly-too-small maroon sweater bunching up around the roll just above his trouser belt. Harry never saw him in casual clothes, and since she vacuumed inside his closet she knew he didn’t own any. Not a sweatshirt or jeans or a ratty pair of sneakers in sight.

The crinkled line between his eyes became more pronounced and she realized she hadn’t actually answered his question.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I didn’t get a good night’s sleep and I’m a little out of it.”

That much, at least, was true. She hadn’t slept except in fitful snatches the night before, or the night before that. When she closed her eyes she saw the lines of the letter Ted Howell Jr. had sent, the stark, unrelenting cruelty of them. Worse, she’d replay the humiliating conversation they’d had after she’d worked up the nerve to call him.

Mr. Castillo’s lips moved and she realized he was talking again. She forced herself to concentrate on him, to make sense of the noise emitting from his mouth.

“. . . cup of coffee in the kitchen. There are some blueberry muffins as well. Did you eat breakfast?”

Harry shook her head. She’d barely eaten a thing the last two days. It was hard to think about food when there was a cold knot in her stomach that never loosened, taking up all the space where a meal should go.

“Have something to eat and a cup of coffee and come back in twenty minutes. I will have finished the shelves on this side by then.”

They were in the big library, which housed not only Mr. Castillo’s special editions—rare and collectible volumes, many of them perfectly preserved or restored—but many smaller props from film sets—the gold box from Cronos, the Necronomicon from Army of Darkness, Sweeney Todd’s silver-chased blades.

These were the props that Harry liked, things from the films she loved that didn’t seem to have agency or personality like the costumes and puppets on the upper floor. They were just incredibly cool objects, and she would marvel that she got to touch them even with gloves.

Today she’d barely noticed what she touched, though her hands had moved automatically through her tasks. She didn’t know what she was going to do, and worrying about it took up every cell of her body.

“Go on, go on,” Mr. Castillo said as she stood in a stupor. He made a hurry along gesture with his arms. “Eat something, drink coffee. You’ll feel better.”

Harry nodded and moved toward the kitchen like a sleepwalker, unsure what to say or do in the face of Mr. Castillo’s sudden gesture of humanity. He usually treated her like an automaton, a cleaning robot that arrived at his home at ten a.m. and left at five p.m. three days a week. He wasn’t unkind; he just wasn’t familiar. He didn’t make idle chitchat. He didn’t invite confidences.

Harry understood why. The press, she knew, had been very intrusive after the tragedy. And Mr. Castillo had made it clear that their relationship was a professional one, even though—or perhaps especially because—she was in his house and among his things.

Now he was telling her to take a break—a break, a thing she’d never been offered before. Mr. Castillo didn’t seem to think breaks were necessary things. He never appeared to take one himself. Normally the only time Harry was able to sit down was at lunch.

I must have been really out of it, Harry thought as she pushed open the door into the kitchen. It was one of those doors that had hinges that swung both ways, which always made Harry think of a housekeeper carrying a tray of dishes, nudging the door open with her hip.

The kitchen itself looked like it belonged to another house, like it had been dropped in Bright Horses by aliens who’d missed their correct stop. The furniture throughout the rest of the house was heavy and dark, with brocaded fabrics and thick curtains and old-fashioned wallpaper all around. The rooms gave off the impression of cobwebs and dust even though everything was spotlessly clean.

But the kitchen was like a display model for a new condo showing. White cabinets, subzero refrigerator, Wolf oven and range, chrome appliances, marble countertops. It was an entertainer’s kitchen, the kind of room made for someone who loved to cook, who loved to arrange plates of food just so and carry them out to guests who oohed and aahed. It was incongruous with Mr. Castillo’s hermit-like nature, just like the guest rooms that were always prepared for anyone who might drop in.

She wondered if these habits were a remnant from his life before, when he did throw parties and have guests stay at his home. Now the beautiful kitchen and the fresh sheets on the beds were phantom limbs, memories of a life he couldn’t feel properly any longer.

Harry made a cup of dark roast coffee. Mr. Castillo had one of those pod machines that she considered too expensive and wasteful. She didn’t think the coffee tasted that great, but it was better than the instant she kept at home.

She found a basket of muffins on the counter and took one, eating it while standing over the sink. Harry wondered who baked the muffins. It was hard to picture Mr. Castillo with an apron over his nice trousers, surrounded by flour and butter and sugar, splatters of blueberry juice on his hands.

Perhaps he had a cook who only came in when Harry wasn’t around, a cook who kept all the surfaces gleaming, because Harry found there was never much for her to clean.

She heard a muffled thud from the other room, a thud that reminded her of the room upstairs.

(And I never clean that room at the end of the hall on the third floor but there’s nothing sinister about it and there’s no one being kept in that room against their will, definitely not.)