Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Greenland: a remote, mysterious, ice-covered rock with a population of just 56,000, has evolved from one of earth's last physical frontiers to its largest scientific laboratory. Locked within that vast 'white desert' are some of our planet's most profound secrets. As the Arctic climate warms, and Greenland's ice melts at an accelerating rate, the island is evolving into an economic and climatological hub, on which the future of the world turns. Journalist and historian Jon Gertner reconstructs in vivid, thrilling detail the heroic efforts of the scientists and explorers who have visited Greenland over the past 150 years - on skis, sleds, and now with planes and satellites, utilising every tool available to uncover the pressing secrets revealed by the ice before, thanks to climate change, it's too late. This is a story of epic adventures, populated by a colourful cast of scientists racing to get a handle on what will become of Greenland's ice and, ultimately, the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 765

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

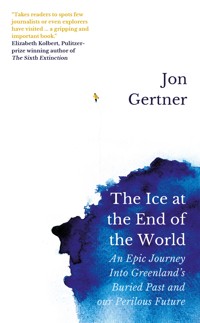

The Ice at the End of the World

An Epic Journey Into Greenland’s Buried Past and our Perilous Future

Jon Gertner

Once again, for Liz, Emmy, and Ben

Ice is time solidified.

—Gretel Ehrlich

Contents

The Ice at the End of the World

Operation IceBridge flight over southeast Greenland (Joseph Macgregor/NASA)

INTRODUCTION

The View from Above

Late one afternoon in April 2015, I found myself standing on the side of a desolate airport runway in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, looking west toward an overcast sky. Next to me stood a group of NASA employees, all of them scanning the same gray clouds. There wasn’t much small talk. As the temperatures dipped below freezing, we blew on our hands and kept our eyes fixed on the horizon. “We’re running late,” Luci Crittenden, a NASA flight operations engineer, finally declared. She looked down at her watch, then stomped her feet to keep off the chill.

Not long after, we heard a dull roar in the distance. And soon enough, we could see it coming—a stout-bellied U.S. Army C-130, trailing a plume of black exhaust. “Uh-oh, I think it’s on fire,” a woman standing next to me, Caitlin Barnes, remarked. I knew this was a joke—sort of. When the aircraft landed a few minutes later, the problem as far as I could tell wasn’t an overheated engine, but old age. The plane taxied down the runaway, made a quick hairpin turn, and came to a vibrating halt in front of us, its rotating propellers making a thunderous racket. If a dozen rusted rivets had popped off the fuselage, or if a wheel from the landing gear had rolled off, I would not have been surprised. The machine looked positively ancient.

No one said much. But then Jhony Zavaleta, a NASA project manager, yelled over the din: “Nineteen sixty-five!”

Apparently, this was the year the aircraft had been built. I wasn’t sure if Zavaleta was amazed by the fact or alarmed. And in some ways it didn’t matter now. For the next few weeks, barring any mishap, the C-130 would fly this group around Greenland, six days a week, eight hours a day. It had spent months in the United States being customized for the task. Under the wings, belly, and nose cone were the world’s most sophisticated radar, laser, and optical photography instruments—the tools used for NASA “IceBridge” missions, like this one. The agency’s strategy was to fly a specially equipped aircraft over the frozen landscapes of the Arctic so that a team of scientists could collect data on the ice below.

The IceBridge program had come into existence at a moment when the world’s ice was melting at an astonishing rate. Our plane’s instruments would measure how much the glaciers in Greenland had thinned from previous years, but the trend was already becoming obvious: On average, nearly 300 billion tons of ice and water were lost from Greenland every year, and the pace appeared to be accelerating. Yet it was also true that hundreds of billions of tons meant almost nothing in the vast expanse of the Arctic. The ice covering Greenland, known as the Greenland ice sheet, is about 1,500 miles long and almost 700 miles wide, comprising an area of 660,000 square miles; it is composed of nearly three quadrillion—that is, 3,000,000,000,000,000—tons of ice. In some places, it runs to a depth of two miles.1 And so the larger concern, at least as I saw it, was not what was happening in Greenland in 2015, or even what might take place five or ten years hence. It was the idea that something had been set in motion, something immense and catastrophic that could not be easily stopped.

Ice sheet collapse was not a topic of everyday conversations in New York or London. Even if you happened to know some of the more unnerving details—about rapidly retreating glaciers, for instance, or about computer forecasts that suggested the Arctic’s future could be calamitous—it was easier to think of the decline in ice as a faraway dripping sound, the white noise of a warming world. Still, by the time I signed on with the IceBridge team, the fate of the world’s frozen regions seemed to me perhaps the most crucial scientific and economic question of the age: The glaciers are going, but how fast? The ice disappearing from Greenland, along with ice falling off distant glaciers in Antarctica, would inevitably raise sea levels and drown the great coastal cities that a global civilization—living amidst the assumption of steady climates and constant shorelines—had built over the course of centuries. But again, the pressing question: How soon would that world, our world, confront the floods?

Not long after the C-130 landed, we clambered up a staircase and stepped into the passenger cabin. We entered a long, cavernous room with a grime-streaked floor that smelled strongly of engine oil. Electrical cables snaked up the walls. Arctic survival packs swung from a ceiling net. I noticed a crude, freestanding lavatory toward the back of the room; an old drip coffeemaker and microwave oven were secured to a table along the far wall, with Domino Sugar sacks piled high on a pallet underneath. Positioned in the center of the cabin, in front of several rows of seats, were banks of gleaming computer consoles and high-resolution screens. And bolted to the floor was a massive instrument that resembled a cargo container you might attach to the roof of your car to haul gear on a vacation. This was a laser tool—an altimeter—to measure the height of the ice below.

On the outside, the plane looked ready for the scrapyard. On the inside, it was a fortress of technology. I took another look around. The science team was already logging on to the computers, readying themselves for the schedule of flight missions that the IceBridge team would follow this year. The pilots, with fresh crewcuts, were introduced to us as aces recruited from the navy and air force. Then they, too, excused themselves so they could check the instruments in the cockpit and get ready.

The first flight, I was told, would leave the following morning at eight-thirty sharp. “Be here or be left behind,” John Sonntag, the mission leader and a native Texan, told me after we walked back out to the tarmac. Sonntag had been deployed to Greenland more times than he could properly recall. He had an easy manner, a friendly grin. But he meant what he said. The work was too important to accept delays. His team had come here, pretty much to the end of the world, to understand how and why trillions of tons of ice were melting into the ocean. They were not acting on the assumption that they would soon find out, but with each flight and each yearly mission, the data piled up: ice lost; water gained. The goal was to gather more and more evidence in the hope that it would ultimately lead us toward an answer—before it was too late.

Kangerlussuaq is located on the west coast of Greenland, just north of the Arctic Circle. For several years, I came in and out of this village with some regularity to connect with flights that were either heading to towns along the western or southern coast of Greenland, or to link up with scientists who were using Kangerlussuaq as a base for fieldwork on the central ice sheet, which begins about twenty miles east of the settlement. In truth, Kangerlussuaq is more of an airstrip than an actual town, a place to pass through on your way to somewhere else. Though its population hovers around five hundred, the only real hub of activity is the airport café. Caught in the half-light of transit, visitors eat and drink here as they await arrivals or departures. There are no highways out of town—indeed, there are no highways or arterial road systems anywhere in Greenland. In winter, to get to another village, you either fly by propeller plane or—if the ice along the shoreline is thick enough—take a dogsled. In warmer months, you might opt for a ferry that runs up and down the coast.

Sometimes, I would find myself stuck in Kangerlussuaq for a weekend, with no flights coming in or going out, and to pass the time I would walk for hours on empty trails in the neighboring countryside or explore the deserted roads around the airport. The town dates back to World War II, when Greenland—a convenient halfway point between North America and northern Europe—became a key outpost for American military defenses and a pit stop for refueling planes. There are few trees in Greenland, and only a modest amount of greenery, but in the Kangerlussuaq region there are wildflowers and willow bushes and soft sphagnum mosses; there are staggering mountaintop vistas, too, over rocky bluffs and hidden fjords and lakes too numerous to count. There are caribou in abundance, as well as musk oxen and puffy white Arctic hares. The breezes are clean and otherworldly. The first time I landed here and took a deep breath, I stopped to wonder if the air was made from some other substance altogether.

On the morning after our C-130 arrived, we took off on that first IceBridge flight. Our route from the west coast was plotted across the island, due southeast, toward Greenland’s rugged eastern coast, where dark, jagged peaks jut up like huge animal teeth from a prehistoric crust of snow-covered ice. It would be a long ride. Greenland is the world’s largest island—about five times the size of California, and three times the size of Texas.2 Just over 80 percent of the land is covered by the central ice sheet. Though it’s home to a population of about 56,000 people, most of whom are descendants of the native Inuit, this is the least densely populated nation on earth. Only Antarctica, on the opposite end of the globe (and, technically, not a country) is more barren, and only Antarctica has more ice.

After we took off, we scudded through a layer of thick clouds for a half hour. But the sky soon cleared, and the white world below came into crisp resolution. The strategy for these missions is not to fly high but to fly low. Staying steady all day at fifteen hundred feet is ideal. There was agreement on the C-130 that the ice sheet, at least from our height, tended to look like handmade paper, the kind sometimes used for fine stationery, with visible fibers and textured imperfections. But the technicians on the flight spent very little time gazing out at the scenery. With the clearing weather, they began scrutinizing their computer screens, watching sine waves and radar images and the data streaming in about the ice below.

At that point, I made my way through the main cabin toward the front of the plane. From there, I could hop up a short ladder to the flight deck and watch, through large cockpit windows, as the pilots skimmed over Greenland’s frozen interior. For three hours we passed above this pale world, until we at last approached the east coast and began trailing the snaking course of big glaciers—wide rivers of ice that flow from the edges of the sheet, down through mountain valleys to the ocean’s dark edge, where they collapse and explode into iceberg-strewn chaos. Without exception, what lay below was a sight of uncommon beauty and uncommon strangeness. Taking in the immense expanse of Greenland from low altitude was like surveying the landscape of some kind of frozen exoplanet. The hard blackness of the coastal mountains, the soft whiteness of the ice sheet—the only color intruding on the scenery was the light blue of the sky and a deeper blue from crevasses in the ice that radiated a luminous, aquamarine glow. Down below there were no people, no houses, no movement. For hours on end, there was only ice and rock, ice and rock, ice and rock. In my notebook I wrote: Someone would think we’d left no traces here at all.

Many of the places below had names, though. And during the course of the day and those that followed, I could piece together from my aerial view the history of an island where men and women had spent centuries charting an apparently vast emptiness that had turned out to be anything but empty.3 Along the coasts, Greenland’s peninsulas, capes, and glaciers bore the names of explorers who had passed this way on geographical expeditions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—French, British, Danish, Inuit, Norwegian, German, and American. Many of these people were fairly obscure, all of them were now dead. But down below were also reminders of a more recent age of science. As our plane passed the center of the island, we roared over coordinates that marked historical sites from the 1930s and 1950s—scientific outposts in the middle of the ice sheet where large leaps were made in our understanding of the earth. These camps were now invisible, lost beneath decades of accumulating ice and snow, but near to where they once stood I could discern a place that was still functional: Summit Camp, a research station located in the dead center of the ice sheet, sited at an altitude of about ten thousand feet. A cluster of buildings comprised the camp. Down below I saw a few tractors frosted white. Then all signs of civilization fell away, and our plane was again zooming low over the nothingness of the ice sheet.

I had to remind myself that it wasn’t actually nothingness. I recalled a story from the early 1930s about a German glaciologist named Ernst Sorge who took one of the first flights over Greenland’s central ice—“the white desert,” as it was sometimes called then—as a passenger in a small airplane. Sorge had already spent a brutal winter in the center of the ice sheet; he had also traversed it many times by dogsled. But the view from above that day was different than what he had so far encountered. It transfixed him. He would later write: “I said to myself, ‘I’m looking at a landscape whose vast simplicity is nowhere to be surpassed on earth, and which yet conceals a thousand secrets.’”4

Thirty years ago, in his book Arctic Dreams, the writer Barry Lopez put forward the notion that “as temperate-zone people, we have long been ill-disposed toward deserts and expanses of tundra and ice. They have been wastelands for us; historically we have not cared at all what happened in them or to them.” Lopez predicted, however, that the value of these places would one day “prove to be inestimable.”5 To a fair degree, this book picks up on his observation and asks whether that moment has now arrived.

Lopez’s gift to readers was his ability to render the poetic complexity of the north and explain how its fragile lands and wildlife were coming into conflict with fishing and mining industries. Other writers, meanwhile, have focused less on the ecosystems of the Arctic and more on the resilient culture of the Inuit, who came to Greenland about eight hundred years ago by way of the sturdy sea ice that connected the island with northern Canada. These books can be especially compelling in how they challenge Western conventions. To read, say, the French anthropologist Jean Malaurie’s description of how in 1951 he watched a northwestern tribe of native men hunt, butcher, and eat a walrus—the blood was drained into a gasoline can and shared between them as qajoq, or soup; the eyes were distributed for snacking; the digested food in the intestine (mussels, mostly) was freed and devoured; and the head, ivory tusks, and the heart, weighing seventeen pounds, were awarded to the hunter who led the kill—is to see how different our twenty-first-century lives, and our twenty-first-century sensibilities, really are.6

This book is mainly about Greenland’s ice sheet—the vast frontier that “conceals a thousand secrets” and is among the most remote and inhospitable places on earth. More specifically, the pages that follow trace the lives of men and women who sought to understand the mysteries above, around, and within that ice. By describing their work, my intention is to tell the story of how we have come to know what we know. Without that knowledge of the ice—without that story—it seems all too easy to believe that our understanding of the Arctic, and of an endangered natural world, is somehow the product of ideology or opinion, rather than the result of hard-won facts and observations.

There are many ways to tell such a tale. The white expanse that covers the center of Greenland began to form about one million years ago when snow that had fallen during the colder months of the year stayed on the ground and endured through summer.7 Greenland is a semi-arid environment, which means that snow accumulations are modest. Still, decade after decade, enough snow began to pile up that its weight and pressure formed it into ice. Eventually, that ice became hundreds of feet thick—and later still, several miles thick. We might for a moment imagine these Greenlandic beginnings: A windy, rocky, barren stretch beset by deep freezes lasting tens of thousands of years. All the while, snow piles grow slowly but inexorably, year by year, and fuse together into an ice sheet, which in turn starts to thicken, flow, and spread in many directions, thanks to additional snowfalls and the forces of gravity. And then, finally—only very recently in geologic time—humans begin to wander onto the ice to try and uncover the secrets it might contain. This book starts at this recent moment in history.

The late 1800s and early 1900s are what we might call the waning days of the age of exploration. The men of that era discussed in the ensuing chapters—Fridtjof Nansen, Robert Peary, Knud Rasmussen, and Peter Freuchen—pursued geographical knowledge while testing themselves against the mortal dangers of the ice. In the years after these expeditions, the pursuit of adventure was eclipsed by the pursuit of ideas; or, to put it another way, a point arrived when the age of exploration was transformed into the age of discovery. In 1930, a German scientist named Alfred Wegener led a team of men on a hellish journey to the center of the ice sheet to set up a winter research station. Wegener’s colleagues, as detailed here, began to use new technologies to cross the ice and investigate it. And in the decades afterward, hundreds of scientists followed in Wegener’s footsteps. In the late 1940s, Paul-Émile Victor, a trailblazing Frenchman, was among the first to perceive Greenland not as the goal of an occasional expedition but as the subject of constant scientific inquiry. Not long after, Henri Bader, a Swiss-American scientist, helped the U.S. military understand the Arctic terrain and began to see the potential scientific value hidden within the ice sheet. This work continues—not only in rarified endeavors such as NASA IceBridge flights, but in ongoing field research that brings teams of scientists to remote locations for weeks or months at a time, often drilling into the ice to collect samples known as ice cores, which contain records of ancient climates, or working to gather other precious information that comes at great financial and human costs.

For many of us living far from the Arctic, it seems reasonable to ask how much relevance we might find in these stories, or in the history of glaciology this book brings to light. Another way to ask that question is to consider whether the past, present, and future of Greenland’s ice is important to how we live now. The answer is no longer in doubt. It is difficult to grasp the full implications of climate change without understanding the work done on Greenland, seeing as its ice has told us (and is telling us still) secrets that cannot be found anywhere else. Foremost is the matter of sea level rise: Within just a few decades, the melting in Greenland and Antarctica will afflict hundreds of millions of people who live or work near a coastal region, leading us into a terrible epoch of human dislocation and economic hardship. At the same time, the collapsing Greenland glaciers, coupled with a drastic decline in floating sea ice near the North Pole, may lead to other potential disasters, such as a change in Atlantic Ocean circulations and a global disruption in weather patterns. “The melting of the Arctic will come to haunt us all,” climate scientist Stefan Rahmstorf declared in the summer of 2017.8

But there’s something more here, too—the possibility of encountering in this remote area, and in these stories of explorers and scientists, an essential aspect of our world too long neglected. We have no shortage of historical works about twentieth-century wars, politics, and cultural upheavals. This book offers an alternative history, running counter to the mainstream, that is sympathetic to the idea that understanding this Arctic island is not only useful but crucial. In the history of Greenland—“the world’s largest laboratory,” as the scientist David Holland once described it to me—we can find not only outsized characters who risked their lives in an unforgiving landscape, but a deeper sense of how scientific discovery happens on an epic scale. In light of this, we might ask ourselves what society does with new knowledge once it is found. How do we build upon it? How should we act upon it? And especially in the case of Greenland, how might it help us let go of the antiquated notion—the notion that concerned Barry Lopez—that the fragile, frozen far reaches of the planet are somehow unconnected to our lives?

I’ve come to see Greenland’s ice as an analog for time. It contains the past. It reflects the present. And it seems capable, too, of telling us how much time we might have left.

On those IceBridge flights, the days seemed to last forever. On our first mission, the engines of the old C-130 throbbed and whined as data about the surface below poured in from radar instruments under the wings and zipped at light speed into the computer servers a few seats ahead of me. The information from our journey would be downloaded and eventually posted on the Web for scientists around the world to see. The afternoon progressed. And in my stiff, military-issue chair I began to sink away: In the dream I was having, we were flying above an endless roll of blank paper sprinkled with Domino Sugar crystals. When I awoke, we were arriving at the ice sheet’s western border and Greenland’s more populous west coast. Soon we passed over the oil tanks and small houses, red and green and blue and yellow, of the coastal villages that held fast to the rocky edge of Greenland, looking westward over Baffin Bay toward Canada, poised on the rim of a silver-white sea of ice. Our flight had followed a rectangular pattern across the center of Greenland, and eight hours after takeoff we were nearly back in Kangerlussuaq, the place where we started.

It is a truism that we take for granted journeys that today are effortless and safe but that not long ago were extraordinary and death defying. Nowhere is this more apt than in Greenland, where travel and science have been utterly transformed by technology. Many months after my tour with IceBridge, after I returned to the United States and began sorting through my notes, it struck me that to truly understand Greenland’s ice—to trace it through past, present, and future—I would need to understand this transformation.

It seemed likely to me that I could locate the start of Greenland’s scientific evolution by returning to a premodern age, just before aircraft like our C-130 could soar above the ice sheet with ease. To be sure, that meant going back in time—back to the polar explorers’ era of headlong risk, back to a period when the reckoning of direction came by way of sun and stars, back to when communications between parties sometimes involved notes stored for months (or years) inside stone markers built on windswept shorelines. It likewise meant going back to Greenland, in person and in archives, to see how the early interrogators of this frozen world, often enduring suffering on an almost unimaginable level, began to uncover its myths and secrets. With that knowledge, I imagined I could start to observe how our understanding of the ice began. I might likewise grasp how the early work in the Arctic, unbeknownst to the first wave of explorers and researchers, had set later events and ideas into motion.

To start, then, it seemed worth considering a risky notion that took hold of two men on opposite sides of the Atlantic at about the same time in the late nineteenth century: As for this great, impassable field of ice in the center of Greenland—why not try to cross it?

Notes

1. According to PROMICE—Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet, operated mainly by the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland—the ice mass amounts to 2.7 × 1018 kilograms. I’ve converted it into English units.

2. This classifies Australia as a continent, rather than an island. Australia is larger than Greenland.

3. I’m indebted to Barry Lopez for this insight: “The land in some places is truly empty; in other places it is only apparently empty.” Lopez, Arctic Dreams (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986), p. 383.

4. Ernst Sorge, With Plane, Boat and Camera in Greenland: An Account of the Universal Dr. Fanck Greenland Expedition (London: Hurst & Blackett, 1935), p. 88.

5. Lopez, Arctic Dreams, p. 12.

6. Jean Malaurie, The Last Kings of Thule: With the Polar Eskimos, As They Face Their Destiny (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1982), pp. 67–71.

7. Although the oldest ice recovered from Greenland’s depths goes back about 150,000 years, there is growing agreement that the oldest parts of the ice sheet date back much further. The Danish glaciologist Dorthe Dahl-Jensen (author interview, Copenhagen, November 6, 2017) explains, “We say that ice has probably covered central Greenland for one million years.” She also thinks it possible that glacial ice exists in Greenland’s eastern mountains that may be far older—perhaps dating back seven million years.

8. Seth Borenstein, “Fast Melting Arctic Sign of Bad Global Warming” (Associated Press, August 14, 2017). As Borenstein also points out, the goal of keeping global warming to 2 degrees Celsius—a tenet of the 2015 international Paris Agreement—is already irrelevant in the Arctic: “Last year [2016] the Arctic Circle was about 3.6°C (6.5°F) warmer than normal.” The weather and circulation disruptions stem from the melting of Arctic sea ice as well as land ice on Greenland. For further reference, see Jon Gertner, “Does the Disappearance of Sea Ice Matter?” (The New York Times Magazine, July 29, 2016).

Part I

EXPLORATIONS

(1888–1931)

Fridtjof Nansen (Library of Congress)

1

The Scheme of a Lunatic

On the old maps of the Arctic—the ones drawn by hand, where geographical features were left blank in places where the world was still unexplored—an area along Greenland’s southeastern coast was sometimes marked as inaccessible “by reason of floating and fixed mountains of ice.”1 In a region so bitterly cold that winter sometimes lasted ten or eleven months, the dark waters were covered by vast and dangerous frozen fields. During the summer of 1882, a Norwegian sailing vessel called the Viking came to this location, only to become entrapped in the icy white sea.

Every morning, a passenger named Fridtjof Nansen would leave his cabin, walk up to the deck, and climb the mast to look out and consider his predicament. Nansen was twenty years old, tall and athletic, with clear gray eyes and a shock of blond hair that often stood straight up. A student in zoology at the university in Oslo,2 he had signed on for the summer with the Viking, a sturdy seal-hunting ship outfitted for icy Arctic waters, to collect marine specimens for his research. From his perch on the mast, though, Nansen could see that the hunting, as well as his studies, would need to be put on hold. All around was the frozen expanse of the Denmark Strait, a body of water that runs between Iceland and Greenland. Jagged white plates, massive and locked tightly together, stretched away for miles in every direction.

Usually, the strategy for a crew locked in pack ice was to wait and hope for good fortune. Wind or sea currents might present a break in the ice and a dark route toward open water—what sailors would call a “lead,” which would mobilize them with great urgency to stoke the engines, so the captain could direct the ship as quickly as possible toward safety.3 If no lead appeared, however, the alternative could be dire. Months could go by. Sometimes even years could pass, in which case food would need to be drastically rationed. And at any time, the icy grip on a ship could tighten.

The literature of the Arctic is rich with descriptions of how it feels to be on a ship fixed helplessly in ice. Sailors often disembark temporarily, to engage in games of strength or skill on the ice floes, or to stage elaborate comedic plays. A ship’s officer might wander onto the ice to play his violin under the midnight sun. Frustration, boredom, and insomnia are typical aspects of the entrapment. So is fear. The sound of ice tightening around a ship is said to be so unbearable that it drives some sailors to the edge of psychosis; it pushes against the wooden shell harder and harder, night and day, until pressure bends the planks beyond mere creaking and they begin to scream. In the worst cases, the ship’s hull is punctured, seawater rushes in, and eventually the ribs and keel explode into splinters. Nansen was aware of a legendary but true story: In 1777, a century before the Viking’s voyage, a dozen whaling ships had all been caught simultaneously in the same east Greenland ice belt that had now snagged his vessel. During that summer, when one ship caught in the ice sank, the sailors would board a neighboring ship or they would make camps on the pack ice—a cruel Arctic variation on musical chairs. The pattern continued until the ice had destroyed all twelve ships, and the men who remained had nowhere to go. They dragged rowboats to open water and headed south, away from the deadly eastern coast. Most tried to row around the bottom tip of Greenland, a distance of several hundred miles, and then up toward the Danish settlements on the island’s more temperate western coast. About 150 men survived the journey. But for every sailor who made it through alive, two did not.

On the Viking, there was no lead in sight. And as the days passed, Nansen, looking with field glasses from his perch on the mast, began to focus less on the dangers of the surrounding ice—he was not easily, if ever, given to fear—than on the contours of the nearby coast of Greenland. He would later reflect that his curiosity “was drawn irresistibly to the charms and mysteries of this unknown world.” By his reckoning, the ship was about twenty-five miles from shore.4 Nansen asked the captain of the Viking if he might be allowed to walk alone over the ice from the ship to Greenland’s shore. It was one of Nansen’s many peculiarities—the embrace of an idea that seemed so risky as to be almost absurd. The captain denied Nansen’s request immediately. But Nansen continued to mull the prospect of the east Greenland coast. From the lookout, he reasoned that the best approach would be to bring a ship close enough to shore, as the Viking was now, so a team of men could jump onto the ice, drag a small boat and supplies to shore, and then do some exploring before returning to the ship.

He filed the plan away in his thoughts. And a few days later, when the pack ice opened and the Viking sailed away, Nansen became too involved with the ship’s regular business to think much more of coastal exploration. Over the course of the Viking’s four-month voyage, in addition to collecting birds and fish and small sea mammals to bring home, Nansen estimated that he shot five hundred seals on the ice floes. The fearless zoology student impressed his shipmates by his skill with a rifle, even as he was privately repulsed by the brutality of the seal harvest. The hunt was a literal bloodbath—work that involved shooting and then flensing the seal, whereby a crewman would slice the pelt off the animal, capture the rich fat underneath (which was used for the manufacture of soaps and oils), and then leave the gore and flesh on the ice floe as carrion for the birds.

It wasn’t until a year later, in 1883, long after he had returned to Norway, that Nansen thought of east Greenland again. A friend was reading the evening newspaper aloud to him. Nansen learned that a Swedish explorer named Erik Nordenskiöld had ventured about a hundred miles into Greenland’s interior, the immense expanse covered by massive glaciers and a permanent sheet of ice. Nordenskiöld had long held the belief, not grounded in any set of facts or observations, that at the center of Greenland’s ice sheet was an oasis—green and temperate, full of reindeer and vegetation. For Nansen a plan came together at that moment: He would organize an expedition that would cross the ice sheet from coast to coast, a feat that had been contemplated but never completed, and test Nordenskiöld’s hypothesis. To be sure, it would be dangerous. No explorer had ever reached the center of the ice sheet, let alone made it across.

His idea had two advantages, though. First, he posited that expedition members could use skis to traverse the ice cap, which would greatly accelerate the crossing. This would be a natural advantage for Nansen, who was among the most accomplished young skiers in Norway. Second, the expedition would not begin near one of the towns on Greenland’s western coast, as all other failed expeditions had done. “It struck me that the only sure road to success,” he later wrote, “was to force a passage through the floe-belt, land on the desolate and ice-bound east coast, and thence cross over to the inhabited west coast.”

Later, he would call his idea “the scheme of a lunatic.”5 But this was not precisely correct. Growing up, Nansen’s friends tried to refrain from saying that a particular challenge—a ski jump, a cliff walk—was “not possible,” because it would incite Nansen to demonstrate that it was. By nature, he tended to combine logic and forethought with an exceedingly high tolerance for risk. He would eventually become an accomplished neuroscientist, but even as a young man he had an appreciation for incentives that sharpen and direct human behavior. The point of his strategy was that once a team was deposited on the east coast of Greenland they would be unable to survive and unable to turn back; the east was too barren to be sustaining, and the barrier of sea ice along the coast would preclude the possibility of rescue by another ship. So they would have no choice but to cross the inland ice. The plan would prove either lethal or perfect. The motto of the expedition, Nansen said, could be, “Death or the west coast of Greenland.”

Probably the earliest recorded mention of Greenland’s ice sheet dates back to an Old Norse text written in the early 1200s—a section of dialogue between a king and his son about the island’s geography, in which the king declares: “When you asked whether the land was free of ice, or whether it was covered with ice like the sea, then you must know that there is a tiny part of the country which is without ice, but all the rest is covered with it.”6

The Scandinavian kings knew about Greenland’s icy landscape because they had traded with settlers there for hundreds of years. The Greenland colonies were divided into two residential clusters, known as Eastern Settlement and Western Settlement; they had been established beginning in the year 985, after several hundred men and women followed a charismatic warrior named Erik the Red there from Iceland. Banished from Iceland for the crime of murder, Erik the Red apparently chose the name Greenland to make the treacherous journey from Iceland to Greenland seem more appealing to potential followers.7 His guile paid off. In Greenland, he succeeded in founding what in time became “the westernmost outpost of medieval Christendom.”8 In a region where mild summers were balanced by long, ferocious winters, the Greenland Norse, eventually expanding to a population of perhaps twenty-five hundred inhabitants, set up a network of farms on the lush meadows around the breathtaking inland bays of the island’s southwestern coast. There, they raised sheep and cows and supplemented their diet with reindeer and seal meat.

The Norse soon established a shipping route with Iceland and Norway. European traders would regularly visit the Greenlanders, who exchanged the valuable walrus ivory and furs they had reaped from their hunting expeditions (and, on occasion, the twisted tusk of a narwhal, the basis for the mythic unicorn) for fabrics, wood, and iron. By modern measures, and by the standards of medieval Europe as well, the Greenlanders’ lives were difficult. Though they enjoyed seasonable summers before the year 1200—after which the climate began to cool, in a period now known as the “Little Ice Age”—the families who lived there were attempting to stake out an existence at a latitude where the practice of agriculture would have been challenging and sometimes impossible. The ruins of these colonies suggest the settlers’ deprivations in later years, and their mounting sorrows—crops rotted by early frosts, skeletal sheep, thin soups flavored by seal bones. A visitor today can only try to imagine their isolation, as well as the winter nights of wracking, subzero cold. The Greenlanders’ physical distance from Europe constituted thousands of miles of ice-jammed waters during an era when a letter carried by ship might arrive a year or two after a sender had sealed it closed with wax. Still, they remained.9

In the late 1300s, the trade routes to Greenland’s Norse began to break down.10 As Scandinavian merchants became more focused on ivory from Russia and Africa, and as increasingly icy and stormy conditions in the North Atlantic made navigation more hazardous, fewer ships made the journey to Greenland.11 There is little in the way of diaries from this period. We can only surmise from small shards of evidence—bones of animals and humans, mostly, that tell us about what the settlers ate and help scientists discern periods of famine or disruption—about a catastrophe that likely befell this small, stranded civilization. The disappearance of the Norse colonies remains one of European history’s supreme mysteries, and theories of its causes abound. The Greenlanders’ end could have come from a change in climate that led to mass starvation or a storm that wiped out scores of the colony’s best fishermen. Perhaps a deadly skirmish with the Inuit settlers ended things, or a plague that spread rapidly ravaged their ranks. (From archaeological evidence, it seems likely that groups of Inuit settlers arrived on the Greenland coast, via the sea ice connecting northern Canada, around the year 1200.)12 What we know for certain is that the last ship to sail from Europe to Greenland probably arrived in Greenland in 1406 and returned to Europe in 1410. Also, we have proof that the Greenlandic Norse were alive from a letter, dated 1424, that made reference to a wedding in Greenland sixteen years prior.13 There was no suggestion that anything at the settlement was amiss. After that, we have nothing.14

Even a century after all commerce and communication with the Greenlanders had ceased, Danish kings discussed the colonies with an air of speculation clouded by years of ghostly silence. Could the Norse have survived all this time on the far, forsaken island? Or had they died off entirely? The prevailing belief was that the Greenlanders had indeed survived, and various attempts were made in the late 1500s to visit the island. Some ships that tried to land on Greenland—especially on the frozen east coast—were repelled by weather and the thick pack ice. But those that succeeded in landing encountered the native Inuit and not a trace of the Norse colonies.15 In 1607 a Danish expedition was sent to find the Greenlanders. Fridtjof Nansen, who would eventually write long, scholarly studies of this period in history, noted that the promoters of the 1607 voyage were so sure of its eventual success “that they even had Icelanders and Norwegians on board, who were there to serve as interpreters when the descendants of the old Norwegian settlers were found.”16 Due to the ice, however, the voyage never made it to shore. Other expeditions were launched later in the 1600s, but those, too, came to nothing. And so in Denmark and in Norway, as the factual details about the Greenland Norse receded and the silence continued, the narrative of the colonies came to resemble myth. In time, the exact locations of the Western and Eastern Settlements were lost.

One day in October 1708, on a remote island in northern Norway, a young Lutheran pastor named Hans Egede went for a walk alone at dusk. Egede, who had just started working in the island’s parish, found his mind drifting. On that evening he recalled a book he had read many years earlier, one that included a description of the Greenland settlements—and that in those settlements “there were Christians, churches, and monasteries.” He began to ask fishermen in his parish if they knew what had happened to the Greenlanders, but he failed to find more details. He then became obsessed with the question of how they had fared.17 A biographer of Egede wrote that as the pastor’s curiosity grew, he resolved “either to discover the old Norwegian settlements, or to form a new one, and to devote his life to the instruction of the barbarous and uncivilized Greenlanders.” His determination must have been remarkable—it took nearly fifteen years of Egede’s petitioning before the Danish monarch appointed him as the official missionary to Greenland. (At the time, Norway was part of the Danish kingdom.)18 With a ship and crew funded by local merchants and the king, Egede departed Europe on May 12, 1721. He arrived safely in southwestern Greenland on July 3 and quickly set up a mission on a coastal island he called the Island of Hope.19 A few years later the mission moved to the mainland, to a town soon known as Godthab, which in time became the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk.

It was the search for the lost colonies that led to the initial exploration of the ice sheet. Not long after he arrived, Egede, with the help of the local Inuit, encountered signs of the vanished Norse—on the fjords of the coast, he explored the foundations of ruined houses and came upon a roofless stone church.20 But a common and mistaken belief at the time was that the Eastern Settlement, as its name implied, had been located on Greenland’s eastern coast—when in truth the two settlements of the Greenland Norse, Eastern and Western, were located on the southwestern coast, about two hundred miles apart. A few years after his arrival, Egede was asked by his Danish benefactors to cross the center of Greenland, from west to east, and search for the lost Eastern Settlement. Having already glimpsed the glaciers of what was then called “the inland ice,” he rejected the idea as too risky.21 “Nothing was more impossible than this project,” he later wrote, “on account of the impracticable, high, and craggy mountains perpetually covered with ice and snow, which never thaws.”22

Not long after Egede had rejected the idea, however, others thought it worth an attempt. The center of the country was by then understood to be filled by “an appalling tract of ice,” yet a trip over the island’s middle was considered a reasonable way—perhaps more efficient than sailing around the island—to get to the east coast and make contact with the possible descendants of the old Norwegians.23 This belief led to a failed ice sheet expedition in 1728, and another in 1751. The latter, led by a merchant named Lars Dalager, penetrated about ten miles into the interior. Dalager’s group spent a few days on the ice, turned back, and camped at the edge of the sheet, whereupon Dalager, exhausted, drank an entire bottle of Portuguese wine and slept for a day.24

In the era before airborne observations, it was only possible to look at the ice sheet by climbing a tall peak on its periphery and, on a clear day, peering toward the horizon, which might give an idea of what was thirty or forty miles ahead. Dalager had barely penetrated the ice sheet; he saw only mountains and more ice ahead. What might be beyond that? More ice? Snowless mountains? A fabled oasis? Dalager conceded that it would be impossible to find out because an explorer would not be able to bring enough provisions for the march across the ice. What’s more, the path, from his brief experience, was subject to such severe cold that he doubted “any living creature could exist” within the confines of the inland ice. His words must have had some cautionary effect: Greenland’s center was being dismissed by one of the few men who had ever walked within it. In subsequent decades, a few scientists made forays around the edges of the ice sheet.25 But for a hundred years after that, Fridtjof Nansen would later write, “the interior of Greenland seems to have lost all interest for the world.”

One Danish official, stationed in Greenland in the 1850s and 1860s, was an exception. Hinrich Johannes Rink was the first outsider to collect native folktales from the Inuit and create an Inuit-Danish dictionary; he was also the first to try to understand how glaciers flow from the edges of the ice sheet toward the fjords and seas. He considered the ice important—not only as a subject for science, but because it was the source of icebergs that cluttered the North Atlantic and endangered ships. He also perceived that the ice was an intrinsic part of the folklore and tradition of the northern native culture. His book on Greenland, published in English in 1877, noted that “the Greenlanders entertain a sort of superstitious awe regarding the icy interior of their country.” The looming, solitary mountains that rise above the ice sheet in some places—nunataks, as they’re known—“are looked upon as the dwelling place of people who have fled from human society and acquired supernatural senses, quickness, and longevity. Besides these, several monstrous and terrible beings have their haunts upon these lonely hills and roam over the great glaciers.”

Rink understood the practical hazards of getting on the inland ice to explore: Venturing in from the shoreline, one would have to ascend the “wall” of the ice sheet and then walk many miles until the ice became “tolerably smooth and level.” He had walked on the periphery and observed that in warmer months the ice sheet was pocked with lakes and rivers that emptied into mysterious holes. These rivers, he remarked, move in “beautiful torrents, which rush along their icy beds until they meet a fissure and turn into waterfalls disappearing in the bottomless abyss.”26 He was describing what we now call moulins.

Still, in Rink’s time, there were perhaps only a few dozen people in the world who had thought deeply about the ice sheet’s geological characteristics and mysteries. Nansen would later note that almost as a rule, explorers saw little reason to look inside Greenland as it became increasingly apparent “that the unknown interior in all probability contained no wealth or material treasures.”27 Curiosity wasn’t enough. The center was a cold place, a useless place, a dangerous place. The center, as long as it remained encased in ice, was a place that Egede, the eighteenth-century missionary, had proclaimed with confidence would have “no use to mankind.”28

On June 4, 1888, a brilliant sunny day, Nansen and a team of five other men boarded a sealing ship called the Jason in Ísafjörður, a seaside village in the remote reaches of northeast Iceland. Nansen and his men had spent the past several weeks making their way here—a journey that began in Norway and took them to ports in Denmark, Scotland, and the Faroe Islands before approaching the Icelandic coast. Six years had elapsed since Nansen had sat locked in ice aboard the Viking, staring out at the dark peaks and ice on Greenland’s shore; he was now going back to attempt the ice sheet crossing he had long envisioned.29

Nansen was much the same person he’d been as a younger man: intense, charming, and strung with complex inner tensions. He had developed an unusual talent for striking an easy intimacy with strangers and rapidly pushing a conversation with a new acquaintance beyond mere pleasantries and into debates on heady subjects—recent scientific discoveries, say, or the critical reaction to the newest drama by Henrik Ibsen. One professor who first encountered Nansen in Oslo at about this time recalled: “This man whose name I had never so much as heard until a couple of hours before [we met] had in these few minutes made me feel as though I had known him all my days.”30 His zeal for conversation and camaraderie could suddenly vanish, however. He carried a Scandinavian burden of melancholy. As a teenager, Nansen would sometimes go alone into the wilderness for the weekend and live off the fish he caught and cooked. As an adult, he would ski alone for days, sometimes late into the night on dangerous terrain, testing himself on trails that connected remote Norwegian towns to one another, seeking only a glass of milk from a farmer along the way to regain his energy for the next leg of the trip. It had become a pattern, in fact, for Nansen to follow ebullient bursts of behavior, singing and dancing and conversing late into the night, with brooding periods of solitary retreat into nature. Sometimes it wasn’t a physical retreat into the wild but a simple descent into silence—he would sit “without moving” for many hours, a friend would recall—and afterward remain “absolutely mute,” again for a span of hours, even when addressed by his companions.31

Nansen seemed to understand his contradictions well: hunter and intellectual; athlete and aesthete; extrovert and self-described “lone wolf.” A man sometimes inclined to flamboyant displays of masculinity (at dinner Nansen had once convinced a ship’s captain to share the heart of a young polar bear he had killed), he was nonetheless an elegant writer who almost always carried a sketchpad with him, so that he could complement his eloquent journal entries with drawings.32 His writings, done with exacting care during his journeys north, expressed a wondrous appreciation of life that he stitched together with dark, mortal thread. Eventually, Nansen would write of the Arctic: “I found [there] the great adventure of the ice, deep and pure as infinity, the silent, starry night, the depths of Nature herself, the fullness of the mystery of life, the eternal round of the universe and its eternal death.”33

His plan for the Greenland crossing of 1888 remained similar to the one he had formulated some years before: He and five other men would be dropped off on the ice floes, as close as possible to the east Greenland coast. They would then use two small wooden boats to transport their equipment and provisions over the sea ice and water, and once they made landfall, they would begin their ascent to the ice sheet and head west.34 The equipment they brought along had involved an immense amount of consideration and engineering. Nansen had experimented for months over what kind of sledges to build (he settled on “a clever and conscientious Norwegian carpenter,” who fashioned them out of strong and lightweight ash with steel runners). He experimented with different cookers and fuels, and he tested various wooden skis before settling on ones of oak and birch, measuring seven feet six and a half inches, that were made with a “free-heel” design similar to those used by modern Nordic skiers. He wrestled with the question of whether reindeer hide was a better material for sleeping bags than wool (he decided it was). It wasn’t merely performance that Nansen cared about; it was also weight. He had originally seemed partial to the idea that dogs or reindeer should be brought along to haul the sledges, but during the planning stages he saw that the difficulties of bringing—and feeding—animals would be prohibitive. The team, he decided, would pull their sledges over the ice sheet by hand. Thus every pound, even every ounce, mattered.

The men were handpicked by Nansen. During the planning stages, he had received about forty applications from volunteers eager to join him on the journey, but in the end he had settled on three Norwegian men (Otto Sverdrup, Oluf Dietrichson, and Kristian Kristiansen Trana) and two native Laplanders (Samuel Balto and Ole Ravna). All were chosen because of their athleticism and skiing abilities; Sverdrup was also considered valuable because of his experience working as a ship’s captain. During the months before the trip, Nansen, Sverdrup, and Dietrichson together made visits to the home of Hinrich Rink, the old Danish-Greenlandic official who had spent decades in Greenland and knew more about the island than anyone in Copenhagen. Rink gave the men tutorials on the landscape and culture and some basic instructions in the Greenlandic tongue. He also showed them maps and discussed possible routes. The aging Dane quickly grew fond of Nansen, but he worried about his blithe attitude and apparent lack of fear. Rink seemed to think that the trip across the ice would prove far more dangerous than Nansen anticipated.35

Just one day after the Jason left Iceland with Nansen’s team, the ship smashed into chunks of sea ice floating in the water, the first hint of the outer edge of the Greenland ice pack. Nansen would recall that the ship moved south to skirt the ice, then west again, and that over the next few days they encountered herds of seals that put their journey on pause so that the crew could engage in a hunt. On June 11, Nansen caught sight of the mountains of the Greenland coast in the distance, probably some sixty or seventy miles away, but separated from their ship by a thick cordon of sea ice. This was to be expected. And so, in the middle of June, the Jason moved near to a cluster of fifteen Scandinavian sealing ships that were stalled in the same waters—often, captains would share dinner or grog together and trade stories as they waited for the ice to open and the weather to improve, so they could proceed with the seal hunt. For the next ten days, in fact, until about June 21, Nansen recalled that his ship “lay knocking about in fog and dirty weather at the edge of the ice, rolling in the swell, and never a seal did we come across.”36

The days after that weren’t much better. The ship moved into fields of pack ice and back out again; seal hunts were launched, but rarely with much success. The Jason trembled and lurched as its thick hull knocked constantly against huge hunks of ice bobbing in the water. All the while, however, the ship moved closer to Nansen’s goal, and by July 14, Nansen estimated they were about thirty-five miles from an area of east Greenland known as Cape Dan, a coastal island just below the Arctic Circle. And then, on July 17, Nansen awoke and saw from the deck that Cape Dan was only about ten miles away, and that the floes between the ship and the shore looked to be loose and passable. “I saw plainly enough that the landing must be attempted that day,” Nansen later recalled. If he didn’t act quickly, the ice floes might lock together into a pack and ruin the opportunity.

He dashed off a letter to a Norwegian newspaper that would be brought back to Norway by the ship. “I think the country north of Cape Dan is the very wildest and roughest I have ever seen,” he wrote, adding that the area had never been trodden by a European, but that it would be soon. “Behind the mountains we here see for the first time the edge of the ‘Inland Ice,’ the mysterious desert which in the near future is to be, as far as we can see, our playground for more than a month.” Nansen sounded optimistic, and by turns romantic, about the coming journey; he said in the letter that he hoped to be home by autumn.

By now it was seven P.M. With the Arctic sun still high, he and his team rushed to lower their gear into their two small boats. “More confident than ever,” Nansen would recall, they made their way down the ladder, pushed off from the Jason, and began rowing toward the Greenland shore. “All of us had the most implicit faith in our luck.”37

The Arctic tends to lure and trap men. Challenges that at first glance seem difficult but surmountable—a short journey by foot over sea ice, for instance, or a brief ascent up a steep hill—somehow, almost invariably, turn ominous. A blue sky blackens, a storm barrels in, and years of careful planning are rendered irrelevant. Diaries of men who nearly died in Greenland, and diaries of men who did in fact perish, are filled with pages of temperature readings so low or wind measurements so high that they seem to defy even the belief of the diarist.

At the start of their journey from the Jason to the shore, on the first day, Nansen and his men moved quickly through the leads between the floes, fighting their way to shore through dark waters strewn with chunks of ice. Occasionally they would hit a broad layer of sea ice and be forced to chop an open water path with axes. Other times, faced with a barrier they couldn’t overcome, they would simply drag their boats over expansive rafts of ice until they came to open water again.

It began to drizzle and then rain steadily. In the meantime, other obstacles arose. Sea ice is not necessarily a flat, smooth expanse like a skating rink. Often, it contains stretches of hummocks, which are formed when enormous blocks of floating ice smash together to form a ragged landscape of white peaks and valleys. One might imagine the torn-down wreckage of a neighborhood of condemned buildings, pushed into a tight pile and frosted with snow. Nansen and his colleagues had to drag their gear over ice peaks that were sometimes as high as houses, and only when these barriers were overcome could the men reach water again and relaunch their boats.

As difficult as the process was, they nevertheless were making progress. By the hour, Greenland’s shore grew closer. “We are so self-confident,” Nansen wrote in his journal, “that we already begin to discuss where and when we shall take our boats ashore.”38