Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

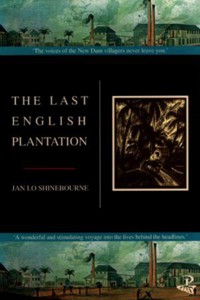

'So you want to be a coolie woman?' This accusation thrown at twelve year old June Lehall by her mother signifies only one of the crises June faces during the two dramatic weeks this fast-paced novel describes. June has to confront her mixed Indian-Chinese background in a situation of heightened racial tensions, the loss of her former friends when she wins a scholarship to the local high school, the upheaval of the industrial struggle on the sugar estate where she lives, and the arrival of British troops as Guyana explodes into political turmoil. "Jan Shinebourne captures the language of movement, mime, silences, glances, with a feeling that comes from being deep within the heart of the Guyanese community. In The Last English Plantation her achievement lies in having the voices of the New Dam villagers dominate the politically turbulent period of 1950s Guyana - A wonderful and stimulating voyage into the lives behind the headlines, into the past that continues creating the changing present. The voices of the New Dam villagers never leave you." Merle Collins. Jan Lowe Shinebourne was born at Rose Hall sugar estate, in Canje, Berbice, in what was then British Guiana. The country was under colonial rule, and she lived through the dramatic events that moved the country when it became independent and changed its name to Guyana. Jan describes her first three novels and most of her writing as being deeply influenced by this period and the rapid and dramatic changes she experienced. She currently resides in West Sussex.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LAST ENGLISH PLANTATION

JAN LOWE SHINEBOURNE

I was wondering if I could find myself all that I am in all I could be.

If all the population of stars would be less than the things I could utter And the challenge of space in my soul be filled by the shape I become.

Martin Carter

1 THE INVITATION

Boysie Ramkarran tapped the gatelatch. Lucille Lehall, six months pregnant, looked up from her washing. Her daughter, June, was playing on the new six-foot water tank in the far corner of the yard where a bushy guinep tree grew and sheltered the tank, only recently tarred, from the sharp mid-morning sun.

‘Good morning,’ Boysie’s deep voice cut through the peace and quiet. He called out to June, ‘How Muluk?’

June saw her mother straighten and drag her soapy arms from the wooden tub. She saw too her look of coldness and dislike as she went to the gate and spoke to Boysie. ‘Yes?’

‘I was wondering if Cyrus might be home,’ Boysie said.

‘Cyrus is always at work at this time of day.’ Lucille spoke her English English, rounding the vowels so that her accent changed completely and distanced her from Boysie. ‘And please don’t call June ‘Muluk’. That is not her name. Her name is June.’

‘Muluk’ was the name Nani Dharamdai Misir called June by. Up to this year she had been called both names in New Dam, but her mother was putting a stop to it now that she was going to go to school in New Amsterdam. Some people said ‘muluk’ meant ‘India’, some said it only meant ‘place’; whatever, Lucille did not like it.

Knowing he was not wanted, Boysie turned and walked away, back to New Dam village. He was a big man with strong shoulders and large arms, who marched rather than walked. Had he been pale, Boysie would have passed for an overseer like Overseer Sam Cameron. Both men wore a thick moustache curled at the ends, both wore khaki clothes, both looked bullish and fearless, but their difference was in their race and position. Boysie lived in the village, was a Hindu and a boiler at the factory, Cameron was a Scotsman, an overseer and he lived in the European quarters.

Boysie always put her mother in her worst mood. Now she was scrubbing so hard on the washboard, her knuckles were bound to be tender afterwards. For the rest of the day, Boysie’s effect on Lucille would linger. She would continue to speak English English and demand of June that she speak like this too. She would snap at her frequently: ‘Speak proper English!’ meaning not correct grammar and vocabulary, which she had taught June well – Lucille’s father had been a Lutheran pastor, a convert from Hinduism – but the imitation of an English accent, which June lacked. It embarrassed June that no one else in New Dam spoke like Lucille.

That afternoon, the English Overseer, James Beardsley called on Cyrus Lehall. On his afternoon walks with his Alsatian dog, Overseer Beardsley did not always confine himself to the European quarters, sometimes leaving the asphalted road to cross the High Bridge into New Dam. When June heard the overseer calling from the roadside, she fetched her father from the kitchen where he was making a cup of tea, then she leaned from the window and listened to their exchanges. Cyrus remained on his landing while the overseer remained at the roadside. For a while the two men exchanged small talk, then turned to what the men on the estate always talked about: work.

‘The three-eights draglines have arrived from Georgetown,’ the overseer informed Cyrus.

‘Oh yes?’

‘It will mechanise irrigation completely.’

‘They already have dragline up by Veira plantation on the East Coast, by I does meet up with the mechanic fellow that side I hear ’bout it.’

‘Oh yes, Cyrus, they’re making quite an impact...’

‘Will put some fellows out of work bad.’ The overseer listened while her father named all the men and boys in the shovel gang, who would be made redundant by the draglines. ‘And that is why the mechanising ’in altogether a good thing,’ her father was saying. ‘You see, although I is a mechanic, I could appreciate how it puttin’ my mati out’a work. Look, in my father day everything was manual. Was pure cutlass use to clean land. Shovel use to dig drain, was oxen long ago use to plough before tractor come. People use to do all forking and half-bank-and-plant, creole gang used to do all fertilising, we had weeding gang, people doing all reaping, bundling, punt-loading. People had was to even walk to canepiece befo’ lorry come. Now tractor got disc and harrow to plough, fork, till an’ everything. Now crawler tractor diggin’ drain, now is chop-and-plant, not half-bank and plant, now airplane will start sprayin’ fertiliser soon I hear, not shoulder-tank, an’ tractor will start pullin’ punt soon. I hear even bulk-loading coming to factory and factory self going to get bigger to help increase production capacity.’ He laughed nervously. ‘Well yes, factory getting bigger, more sugar getting produce but you need less men to do it because of all the mechanising. What a t’ing. Grinding season going get longer, and ratooning too. From 25,000 capacity, I hear we going aim for 50,000 capacity. I hear everything going change in factory too, from juice, clarifying, evaporating, crystallising...’

Although her father said he did not like Overseer Beardsley calling on him, when he did, he could not stop talking. More plantation talk followed until June found herself not listening any more, then drifting inside to light the lamps and the mosquito coils.

That night, Boysie returned with some of his men. The family were at their dinner when they heard Boysie call up. ‘Come Cyrus, come man. We want to talk to you.’

Lucille gave her husband the look of reproach she really wanted to direct at Boysie. ‘Tell him you still having your dinner.’ She never used her English accent with Cyrus.

Cyrus left his half-eaten dish of hassa and tomato curry and went to the window. ‘What it is you want, Boysie?’

Boysie’s voice reached them again. ‘A talk with you, Cyrus. Come down, man.’

‘I eatin’ dinner. You have to wait.’

Cyrus returned to the table and resumed his meal, but Lucille was now in a bad temper, her meal spoilt by Boysie’s presence outside. Sitting near her, June sensed all her tension.

Lucille declared, ‘That man has no manners, none at all.’

Cyrus sighed and drank from his cup of water. ‘Maybe they come to arrange for the weeding on Sunday.’

Cyrus was always hopeful that Boysie and his men would join in the work of maintaining the village. Since the Sugar Industry Labour Welfare Fund had been established, the local government paid the village councils a small amount to maintain the villages. The Fund also provided other advantages but New Dam was slow to take them up because Boysie and his men were hostile to it. They felt that the fund as well as the Village Council had been created by the Governor and the overseers. Boysie argued that it let the estates ignore their financial responsibility to maintain the villages; they should spend the sugar profits on paying the workers a good wage instead of pocket money on a Sunday.

Lucille knew all this. She told Cyrus, ‘I doubt Boysie will help with the weeding.’

After dinner, Cyrus descended the stairs to meet Boysie and his men. June went to the landing and looked on. At this time of night, seven o’clock, it was the kerosene lamps in the cottages which provided all the light. There were only four lantern posts along the public road in New Dam, one here outside their house which was Lot no.1, the others strung out at equal distances to the end of the village. Theirs was the first house which you came to when you approached New Dam, going towards New Forest. By nine o’clock the village would be covered in darkness – fuel was expensive. Now, with all the lamps alight, the cottages, yards, paths and greenery were fretted with light. There was noise too: dogs barking, crickets and frogs calling, the humming of William Easen’s small electricity generator next door. Sometimes you could hear Mr. Easen’s large Ferguson radio, the only radio in the village, when it was working. A baby was crying, children were still playing in the yards and the noises of cooking and washing could still be heard. Any visits to be made, anything to be discussed, had to be done now, between seven and nine, between the last meal and sleep.

Cyrus asked Boysie, ‘What I can do for you, Boysie?’

‘I hear that Overseer Beardsley been here to see you this afternoon.’

There were five men with Boysie, not all from New Dam, only Jagbir and Tulsi were from New Dam. This year, Jagbir was working as a casual labourer – June had overheard her father telling her mother this. Jagbir worked half at the sugar estate, half at the rice mill, the sort of thing that made a worker unpopular with the overseers. They could ask him to leave the plantation and live somewhere else. Jagbir could be without a job and a home next year; this was why he followed Boysie, who liked to take up the cause of such men.

Cyrus asked, ‘What that is to you?’

Boysie replied, ‘It is important we know what these overseers want when they take it on themselves to walk into our villages.’

Cyrus challenged him, ‘What do you think Beardsley was doing? You think he was asking me to burn down New Dam or something?’

Boysie laughed, ‘You naive you know, Cyrus. You don’ work on plantation so you don’ appreciate...’

Cyrus’s voice rose with impatience, ‘Look he’ man, don’ talk to me as if I is some fool, man. I know what is what. My father work on this estate all his life.’

‘As a foreman...’

‘He start off as a stableboy and work hard too fo’ people rights.’

Judgements about the rights and wrongs of their families, family honour, always entered the conversations between Cyrus and Boysie. Both men were born in New Dam. Cyrus’s father, Lou, was one of the few Chinese men who had stayed on the sugar plantations as labourers. Lou had worked his way up to a foremanship, earning himself a right to live in the junior staff compound where the standard of living was much higher than New Dam’s, though much lower than the Senior Staff compound where the overseers lived. Lou had chosen to stay in New Dam with his wife, Jaswanti, who had been an orphan from the Essequibo, whom he had married by arranged marriage. Up to the age of eighteen, Cyrus had worked on the estate as a mechanic’s apprentice. Now he was a self-employed mechanic, sharing a workshop at Palmyra Village with two others.

If Cyrus had not been so involved in community affairs – the maintenance of the dams, petitioning for electricity and water supplies as well as medical and educational improvements – Boysie would not have had so much cause for confronting him, for they had been schoolfriends. There was one important difference between them though. Cyrus knew and understood Hindu customs, but he chose not to practice them, and his marriage to a Christian finally separated him from Hindu practices. Boysie, though not a devout Hindu, did maintain some customs. Often, he could be seen in his yard in the morning doing his puja, sprinkling water at the rays of the sun. Cyrus had been taught these customs by his mother. In his childhood he had spoken Hindi, his head had been shaved twelve days after his birth, and the Pandit had consulted the patra and chosen a name for him, Dushyand, after one of the kings in the Shakuntala stories. Up to her death, his mother had called him by his Indian name, and by hers, Narain, which meant celestial light. Boysie had called Cyrus by his Indian name when they were children but now used his Christian name.

Cyrus asked Boysie, ‘When you going help we weed the parapets and clean the drain? Whatever happen we still have to fight unsanitary condition and disease. If we don’ build up the backdam, all them house aback goin’ get flooded and old Jairam and Charu sickly an’ can barely move in they house.’

‘Tha’s na’ we job,’ Boysie retorted. ‘Is the blasted estate fault the bleady canal floodin’.’

‘I don’ disagree, is their job, but they not doin’ it, and the Welfare Fund giving money to do these jobs on a Sunday, we may as well do it. Sometimes you have to act in emergency and fight another time, Boysie.’

Boysie insisted, ‘Now is the right time to fight. They introducin’ cut-and-load, doing away with cut-and-drop. Now them boys going get they back break rass. You know how them canebatch heavy? Now they gat to hoist them ’pon they back an’ carry them sometimes so much hundred yards to punt! Overseer don’t want pay people to carry the cane no more so cane-cutter got to carry it now! You ’in see overseer t’ink we no better than brute animal?’

‘I support you against cut-and-load one hundred percent.’

‘You tell Overseer Beardsley so when he been here to visit you today?’

‘Yes, I tell him so.’

Boysie sucked his teeth in disbelief. ‘And what he say?’

‘He say he think it bad too.’

Boysie laughed loudly. ‘Good, I glad to hear it. Let he tell Manager Smith them too and let all’a dem take they backside outa this country.’

‘They will go. One day, our own government will be running estate. I not worried like you whether the overseer will go or stay. I know this going be the last English plantation...’

Boysie muttered darkly. ‘Last one in truth...’ There was a pause. Boysie had found out what he wanted but he would leave only after he had had the last word. He turned and pointed in the direction of the forest. ‘They used to have plenty Dutch plantation up the river. African slave rebellion and river finish them off one by one. This is the last plantation lef here in Canefields.’ Boysie slapped his chest. ‘I am the man will make sure this is the last English plantation.’ With that, he turned and walked back to the public road with Jagbir, Tulsi and the others. But something was nagging him. He turned back and called to Cyrus who had moved away from his gate:

‘You sure he didn’t come here to spy? You sure he din’ say anything ’bout guns? Overseer McKenzie tell we how they storing up guns to stop we striking. Them British soldiers and warship bring plenty guns – McKenzie tell we so.’

Cyrus laughed. ‘Guns, Boysie. Well you really believe this is cinema. McKenzie like to threaten people. He want you to believe he. No man, Overseer Beardsley come yesterday on personal business.’

Boysie returned to the gate. ‘Personal? What personal?’

Cyrus said, ‘He got a sick daughter June age. He ask if June could go an’ visit she, see if she could raise the child spirit.’

Boysie sucked his teeth. ‘Wha’ you want send you child to overseer house for? Let he find overseer child to play with overseer child. You is Chinese and Indian mix and you wife is pure Indian. How Beardsley could ask you? He should ask he own mati...’ Boysie now turned and left finally.

On his way into the cottage Cyrus ruffled June’s hair. He went to the kitchen where Lucille was scrubbing the pots. He put a pot of water on the kerosene stove and lit the fire, then he sat at the table to wait for it to boil. June sat opposite him but he avoided her eyes.

She had never visited the European quarters. Until now, her whole life had been spent in the village, at school or at home. Occasionally she accompanied her mother on a shopping trip to New Amsterdam. Every New Year’s eve a busload of villagers usually visited New Amsterdam where they could walk up and down the streets gazing at the bright Christmas trees which were displayed in the windows of the houses there. The young men would join in bursting balloons and firing squibs in the street. In a month she would be starting secondary school in New Amsterdam. Her feelings about it swung from excitement to anxiety.

The flame under the pot was licking round the sides, blackening it. It would be another pot for Lucille to scrub. Her work never seemed to end.

Cyrus spoke to June. ‘Young lady, it’s time for you to go to bed.’

She contradicted him. ‘I don’ want go.’

He commented, ‘You too own-way.’

She asserted, ‘I not going to no Overseer Beardsley house.’

He gave her a cutting look. ‘Who told you anything about you going to Overseer Beardsley house? You been listening to my conversation? And anyway you will do as you are told, whatever it is.’

She shouted, ‘No!’

Lucille stopped scrubbing and came to the table, her apron damp, her soapy hands clutching the handbrush. ‘What’s this?’

Cyrus sighed. ‘When Overseer Beardsley visit he ask if June could go and visit his daughter, the sick one, Annie.’

Lucille frowned deeply, ‘He asked you?’

‘Yes.’

‘That is strange. Why he ask you?’

‘I don’t know.’

June said, ‘I don’ want go no overseer yard.’

Her mother shook the brush at her. ‘Speak properly. Say ‘I don’t want to go’, not ‘I don’ wan’ go’. I’ve told you, I won’t listen to anything you say if you speak it so badly. You’re starting school in New Amsterdam soon and if you go there speaking so badly you will be left back in your work. You know very well how to speak proper English. Why you prefer to talk that terrible Creole?’ She sighed, turned and returned to the kitchen sink.

The sink was a large wooden window box which she had to lean over. Two enamel buckets of water always stood at the ready, along with the bars of Zex soap, Vim and wire scrubbers which she used. Lucille busied herself again with scrubbing the day’s used pots. Her household labours and her ambitions and hopes for June and the child which she carried inside her fretted her enough without Overseer Beardsley adding his family worries to hers.

It was difficult for June to be angry with her mother. Her anger was mixed with love, especially now as she watched her with her bulky womb covered by the dirty, wet apron, pressed against the window sill, her face worn and tired from the day’s work. Although there was bread in the bread bin, tomorrow she would rise at four in the morning to cook a hot breakfast of roti, dhal and calaloo and shrimps for Cyrus – a meal he would also take to work in a saucepan for his lunch. The early rising and cooking was a custom of the poor Indians, the one custom of his mother’s which Cyrus liked Lucille to retain. Now Lucille was calling, ‘June, come and help me wipe and put away these pots.’

Her father insisted, ‘No, let her go to bed. Is late. I will do it.’ He pointed June in the direction of her bed, then went to his wife, took her arm and drew her away from the sink. ‘You should leave these pots till tomorrow or just scrub the outside twice a week. You don’ have to have the whole pot shining like silver every night.’ He sucked his teeth wearily, took up the towel and began to dry the pots. ‘You should be resting more now, not less.’

Lucille’s mind returned to Overseer Beardsley now. She said, ‘I don’t understand why he should ask us. The senior staff is full of white children and the local overseers’ children, and there are girls in the junior staff compound June’s age.’

‘He said is because Annie going start school at New Amsterdam High School too, like June. A lot of those children are Roman Catholics and will be going to the Catholic schools, and other children will be going to the non-religious school. That’s what he said. But he said too that Annie don’t have friends. I think he said she used to go to the Catholic school in New Amsterdam but had some trouble there. He said too his wife is a strong Anglican. I suppose because you is an Anglican and June goes to church too...’

The mention of June and church only irritated Lucille. She declared, ‘June is a heathen. Mistress Beardsley is wrong to think she is a good Anglican. You should tell Overseer Beardsley the trouble I have getting her to go to church. The devil has that child soul. She prefer to go to the Hindu weddings, matikore, to kali-mai and queh-queh, but come Sunday morning you know very well she locks herself in the latrine or the bathroom. You don’t set her any example. You only ever went to church when we got married and when June was christened. As for your language, you don’t bother to speak English...’

He sighed. ‘Lucille, you just letting off a lot of steam. Let us come back to the matter at hand. Beardsley say Annie gets bullied, can’t stand up for herself. What we going to tell him?’

Lucille snapped, ‘So we, June, is just her last chance?’

Cyrus sighed. ‘The girl sounds very sick. Beardsley say she don’ eat at all. He is a worried man. I feel very sorry fo’ him.’

‘Let him send her to a doctor in England.’ Then she recanted. ‘It sounds bad, really bad. What could make a child like that? They have a big house, all the facilities. Mistress Beardsley have servants, she can take care of her children. What is she doing about it?’

‘He said she try and try but can’t get through to the child at all.’

‘It sounds very strange to me.’

June said again, ‘I don’t want to go,’ pressing her parents to refuse the Beardsleys.

Cyrus seemed not to hear her. ‘To tell you in truth, I feel sorry fo’ them.’

June repeated, ‘I not going.’

Both her parents gave her a look of rebuke and her mother said, ‘When there is sickness and you are asked for help you must never refuse. It is one thing you never turn your back on. Families must help each other.’

June disagreed. ‘The overseers not our family.’

‘No, but they are still families. Being overseers don’t mean they not human. Not all of them are bad, and certainly Overseer Beardsley is the best we ever had. I don’ know how he ever turn overseer.’ When she became introspective Lucille lost her uncertainty. Now she was lapsing into her natural voice and was not conscious of it.

The pot was boiling. Cyrus prepared two cups of green tea and a cup of cocoa for June. Lucille came to the table and sat down next to June, then opened the large tin in the centre of the table and drew out the two elongated loaves of bread. Cyrus brought a jar of guava jelly and a tub of margarine to the table. From the shelf June took down plates and knives. Lucille prepared the bread. This was the last ritual before they retired to bed.

Cyrus said, ‘Boysie tell me we must not send June there.’

Lucille frowned. ‘What did he say?’

‘That they are white and we are not.’

‘That man is so racial,’ Lucille commented bitterly.

‘Boysie is not really racial. I t’ink he was really talking politics. You know how people always mix up the two. He was only reminding me Beardsley is an overseer.’

‘Say what you have to say without making excuse for Boysie. I don’t like him. He has no right to be passing comment on what we should or shouldn’t do. I detest that man. He has no interest, either, in improving our living conditions. He just likes to bear grudges, to fight. You know what his name means? The last part of it – karran – means fighter, but the first part, Ram, means he is a man in the service of god, a fighter in the service of god. Well, Boysie like to fight for the sake of it which is why some people call him by the name Karran and not Ramkarran. He makes me ashamed to be his race...’

Cyrus cautioned her, ‘Don’t talk with so much passion, Lucille. You allow Boysie to upset you too much. You think he is critical of you but I never heard him criticise you. Is just his way of life you don’t like, especially the way he keeps women in their place.’

‘He thinks he is lord and master...’

‘We not talking ’bout Boysie really. We talking ’bout Beardsley and the thing he ask us.’

The smell of the mosquito coil was now strong in the cottage. The village was darkening as the lights began to go out. June felt her eyelids heavy with sleep. There was only one bedroom in the cottage. She slept in the corner of the partition which separated her parents’ bedroom from the rest of the cottage.

Cyrus drew in his breath and turned to June. ‘I think you have to go and see how you could help out, June.’ Then he yawned deeply.

2 THE VISIT

On the day that June was to visit Annie Beardsley, her mother washed, starched and ironed her best dress and, at five o’clock, she set off on her cycle for the quarters where the overseers and their families lived.

That part of the plantation was divided into senior and junior staff compounds large enough to hold four of the workers’ villages. The Manager, Bill Smith, had the largest house, which stood on fenced land large enough to take one village. He lived there with his wife and several servants. Their children were at school in England. Overseer Beardsley was the second deputy manager. His house, his land and trees were half the size of the manager’s. The first deputy manager was a Scotsman, Edward McKenzie, whose house, land and trees were in exactly the same proportions as Overseer Beardsley’s. The other overseers lived in small family and bachelor bungalows which were maintained by workers and patrolled by security guards. All these overseers and the managers were called ‘senior staff’. Formerly they had been only English, Scottish, or Welsh, but it was now the practice to employ and house in the European quarters one family and one bachelor of each Guyanese race.

The junior staff were local people, workers who were at a level between the overseers and the labourers. They worked in the office, the dispensary and in semi-professional positions. The junior staff compound was crowded with cottages only a little larger than the cottages in the villages, but they were furnished by the estate, and enjoyed running water, electricity, and maintenance services provided by the estate. Like the local overseers in the senior staff compound, the junior staff were a new class of people.

All this was separated from New Dam village by the sideline canals and shrubby wasteland where a few coconut trees grew. In the middle of this space stood the Anglican church and the cemetery. Canals and drains separated the living quarters. Often, the overseers could be seen on their verandahs surveying the flat land around their compound with binoculars. The overseers’ quarters were guarded strictly. No one could enter without a security check. In the grinding season, the canals and culverts were patrolled by security guards.

Ten minutes of cycling and she reached Overseer Beardsley’s house. There was a security guard at the gate. He telephoned the house, then opened the gate and waved her in.

She rolled her bicycle in and began to walk. The guard encouraged her: ‘Cycle up, cycle up, is a long way in.’

The bicycle was unstable on the gravel path. She passed a poui tree, then a row of flowering shrubs on either side. The further into the garden she moved, the more it enveloped her. It was very cool because there was so much shade from the sun. The light breeze spread the perfume of the flowers everywhere. None of the plants or trees looked in need of care; they bore no dying leaves or branches. The borders were clean and raked, the huge green lawn a carpet which spread itself into the corners of the garden. All the flowers which her mother loved, and some which she had never seen, grew here: powder puff, poinciana, cassia, both pink and yellow, pink and yellow poui too, poinsettia, lilac, jungle geranium, jasmine, bougainvillia, and there were roses, orchids, lilies, ferns and unfamiliar plants with coloured leaves.

Lucille loved flowers as if they were her soul; if she had been granted the time and space to cultivate them, it would have been as if her own soul flowered. Their yard in New Dam was cluttered with as many fruit trees and vegetables as they could fit in: mango, guinep, starapple, papaya, gooseberry, guava, golden apple, pepper, calaloo, corn, bhaigan, same, ochroes, squash, peas, shallot. Lucille could only squeeze in the flowers and decorative plants in pots and hanging baskets, nailing them to the trunks and branches of the trees and along the front and back stairs. Grass was an enemy in their garden; it took up too much space. Here in the Beardsley’s garden there were several standpipes near the fences, and long green hoses trailed from them. Lucille had to pay the small boys in New Dam two cents for every bucket of water they fetched from the standpipe to keep the garden watered. The fetching of water from the pipe was one of the jobs June had done as soon as she could carry a saucepanful of water. Now that Cyrus had built the new water tank it would be easier.

June rolled her bicycle under the bottomhouse and noticed then the small cottage which stood beside the house. This was the head servant’s cottage. It was painted white, with white lacy curtains in the window and a green zinc roof. The small garden round it was decorated with whitewashed rocks and flowering plants. The door of the cottage opened and a servant appeared, in a green dress, white apron and hat. She looked at June, said nothing at all to her and walked up the back stairs of the house.

After a few minutes another servant, dressed in the same uniform, appeared on the stairs. She signalled June to follow her and led the way upstairs. The door was covered in green netting in which were entrapped a few dead flies and mosquitoes. When it was closed behind her June found herself in a kitchen four times the size of her cottage.

‘Hello, you must be June.’ The English voice belonged to the woman who was leaning against the sink. She was preparing green plantains for making chips. June guessed she was the wife of Overseer Beardsley. She spoke again, this time to the younger servant. ‘Claudette, give June a glass of lemonade.’ Then she pointed to the chair which stood between the refrigerator and the door, ‘Sit down, you must be tired from cycling.’

The chair was very hard, the back straight. When she sat in it she found herself wedged tightly between the door and the refrigerator. There was the warmth of the sun on her right arm and the cold of the refrigerator on her left. Claudette brought her a glass of cold lemonade. Mistress Beardsley returned to peeling and chipping the plantains. The two servants were working quietly. Claudette was wiping the dishes again and the older woman was sweeping the floor. There was silence between the three women as they worked.

Mrs. Beardsley peeled and cut the plantains expertly, like a local woman. She was tall and thin with short, wavy, reddish-brown hair. Her eyes were very blue, her nose crooked and thin, her lips thin and red, her face thin, her skin slack and lined. She was not beautiful but her make-up and dress made up for it. Women in the village did not wear make-up like this. Her face-powder, rouge and lipstick were subtle and June knew that Lucille would admire the cut as well as the quality of her dress. Lucille used only face powder, the same she had used since she was a young girl. The women labourers wore no make-up at all except for blackpot, the soot which women collected on the cooking pot which they used as eye shadow. The young women who experimented with cheap make-up brought by salesmen from New Amsterdam were labelled ‘wild’ and they did use the make-up wildly, rubbing rouge thickly on their cheeks and eyelids and so much lipstick their lips became red slashes in their faces.

Mistress Beardsley spoke to her again. ‘So you will be starting secondary school soon?’

June nodded.

Now Mistress Beardsley took off her apron and wiped her hands. ‘I will fetch Annie now.’ She turned to the older servant, ‘Mavis, put the oil on now please and cook the chips when it’s the right temperature. Use fresh oil please.’

‘Yes ma’am.’ Mavis answered.

June waited with the refrigerator humming in her ears. The servants pretended to ignore her. Soon Mrs. Beardsley returned to the kitchen.

‘Come, June.’

A long, wide corridor separated the kitchen from the rooms at the front of the house. June was led into the middle doorway, into a room larger than the kitchen. Through the row of open windows she saw the view through which she had just cycled. The public road was almost hidden from view. This room was as much a dream as the garden and the kitchen. The chandelier, the three large mirrors on the walls, the glasses in the cabinets, the ornaments, polished floor – all were clean and shining in the light which poured through the windows. The wooden walls were painted cream, there were no bright colours here. There were large armchairs and a settee with brown cushions. The paintings on the wall were of sea-views which looked English, windswept and cold.

Mistress Beardsley turned to the doorway and said. ‘Here’s Annie.’

Annie entered the room but remained leaning near the doorway. Her appearance gave June a fright; she was unnaturally white.

Her mother took her hand. ‘Don’t lean, Annie, stand straight. Come and meet June who’s come to play with you. June is starting at the same school as you are in three weeks.’ Now she spoke to June. ‘You and Annie play downstairs. June you go first, then she will follow.’

The front door was nearest. June made for it but Mistress Beardsley stopped her. ‘No, use the kitchen door.’

June walked through the kitchen and caught the servants laughing. She ran down the stairs.

In the garden she sat on the bench under a poinciana tree. The house was full of what her mother called ‘facilities’ – the piped water, electricity, the refrigerator, the stove, washing machine and other machines larger than June thought they would be, larger than those she saw in the shop windows in New Amsterdam, and china, cutlery and furniture in quantities. June decided she did not like it here at all. It was strict and unfriendly because of Overseer Beardsley’s wife who liked to give orders, and all the space seemed wasted.

Annie came slowly down the stairs. She was as thin as her mother. Her hair was very white. She resembled her mother with the same thin face, nose, lips and eyes, but there was life in Mistress Beardsley’s face, look and movements, plenty of life, there was none at all in Annie’s. June could only compare her to very old, sick people, but Annie was a child. She stopped at the bottom of the stairs. June did not move. She felt as if Annie were a bird or some rare creature she did not want to frighten. She pretended to ignore Annie and slowly the white girl began to walk towards her.

Annie sat on the grass, a few yards from June, in the shade of a cherry tree.