6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

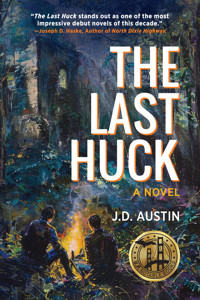

The Last Huck stands out as one of the most impressive debut novels of this decade. --Joseph D. Haske, author of North Dixie Highway Jakob, Niklas and Peter Kinnunen grew up playing together on their family's berry farm on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan's U.P. The three of them inherit the land when their beloved uncle passes away, but Jakob goes to prison and Peter, who goes broke during the 2008 financial crash, calls Niklas and suggests they sell the land for fast cash. Niklas fights back against Peter, but Peter convinces Niklas to take a trip up north, from their homes in Milwaukee, to visit the place and get closure. Haunted by their childhoods and the absence of their beloved Jakob, they spend the weekend drinking, fighting, reminiscing and trying to figure out whether or not to sell. Woven together with moments going back four generations, The Last Huck is the saga of a family ravaged by time and modernity, yet holding on to one another for dear life.

"In his first novel, J.D. Austin vividly captures the painful conflicts among the young men as they spend one last weekend in places that were the scenes of their happiest childhood memories."

--Jon C. Stott, author, Summers at the Lake: Upper Michigan Moments and Memories

"We are a large country with many regional literatures. I find the analogy between the 19th century regional novel and J.D. Austin's The Last Huck provocative and literate."

--Donald M. Hassler, Professor Emeritus of English, Kent State University

"The adventure that ensues not only immediately draws the reader in, but does so in a fashion that makes it virtually impossible to put the book down. It is always a joy for seasoned sojourners to witness young talent, such as J.D. Austin, blossom and flourish as we pass through this life."

--Michael Carrier (MA NYU), author, Jack Handler Murder Mysteries / Hardboiled Thrillers

"The Last Huck stands out as one of the most impressive debut novels of this decade. The characters, sardonic, clever, and intensely authentic, efficaciously propel Austin's masterful narrative through the backdrop of Michigan's Upper Peninsula like skate blades cutting Lake Superior ice in late winter. With this splendid, unforgettable, first effort, J.D. Austin proves himself a name to watch out for in American letters."

--Joseph D. Haske, author of North Dixie Highway

J.D. AUSTIN has resided in the Keweenaw since 2019. He has worked as a kayak guide, ski technician and stage carpenter, among other vocations. Austin's fiction has appeared in The Incandescent Review and U.P. Reader Volume 7. The Last Huck is his first novel. From Modern History Press

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 364

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

The Last Huck: A Novel.

Copyright © by J.D. Austin. All Rights Reserved.

Learn more at JDAustinStories.com

ISBN 978-1-61599-805-0 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-806-7 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-807-4 eBook

Published by

Modern History Press Phone 888-761-6268

5145 Pontiac Trail Fax: 734-663-6861

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

Distributed by Ingram Group (USA, CAN, EU, UK, AU)

Author photo: Jake R. Bartz

Cover art: Frankie Mayfield

Cover design: Doug West

For Ann Lewis Austin

Contents

1 Late August, 2009

2 The Beginning

3 Friday, August 27, 2009 5:37 p.m.

4 The Rags of Time

5 Friday, 7:02 p.m.

6 Early Summer, 1901

7 August 2009, Friday, 7:41 p.m.

8 Saturday, 5:17 a.m.

9 Summer, 1913

10 Saturday, Midday

11 Winter, 1937

12 1999, Marquette

13 Houghton, Saturday, 11:14 a.m.

14 Saturday, 12:41 p.m., Milwaukee

15 Saturday, 5:04 p.m. Houghton

16 Winter 1935, Hancock

17 Sunday, 1:09 p.m.

18 Sunday, 6:28 p.m.

19 Monday, 11:39 a.m.

20 Tuesday, 5:31 a.m.

21 Thanksgiving Day

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“Thy life is not thine own to govern, Danny, for it controls other lives. See how thy friends suffer! Spring to life, Danny, that thy friends may live again!”

– John Steinbeck, Tortilla Flat

“Everything I’ve ever let go of has claw marks on it.”

– David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

1

Late August, 2009

Halfway between Houghton and Baraga, Niklas noticed a cluster of wooden crosses in a patch of wildflowers on the outside edge of a tight curve. For a second, he wondered why. And then, a second later, he remembered why. And then they were gone.

Peter Kinnunen arrived at his wits’ end on the third Friday of August. His son had just returned from the doctor’s office. His wife, who’d driven to the appointment, was crying in the bedroom.

He took out his cell phone and stared sightlessly at his cousin Niklas’ name on the screen. He flipped the phone shut and went into the bathroom. After a few seconds he came out without a flush. Face twitching, he took out his phone again and called Niklas. While it rang he gritted his teeth and prepared lines in his head. Nik picked up after three rings.

“What up?”

Like a deer in the headlights, Peter froze against his own best interest. “Uh, Nik, I… do you have a moment?”

“Yeah, sure, what’s up? I don’t want to go to Shakers tonight or probably ever again, if that’s what you’re asking. I thought I was going to die last time.”

“No, I, uh… no, it’s not that.”

“Thank goodness. What’s up?”

Peter, frozen, was unsure of how to proceed. “Well, man, look. I’m running out of money, literally, I think… I want to huck it up to Uncle Jussi’s farm and stay for a weekend and see about maybe, uh… selling it.”

Niklas let a sinister silence hang. “You mean our farm?”

“Yes. Yes, I know, and I know this sounds bad.” The words tumbled out of Peter’s mouth like rubber balls on concrete. “I know how special it is to us, to you especially. But we haven’t even been up there together since the funeral, since the place became ours. Our lives have gone in different directions. And I’m broke, man, I’ve thought about this a long while.” The idea had occurred to Peter two nights ago, which, in his current state of mind, was a long while. “Look,” he continued, “Of course you and Jakob would get your share. But let’s be for real. He will need the money, too.”

Terrifyingly calm, Niklas asked, “Do you hear yourself?”

“I’m serious, dude. We’re all broke and we all live south of Crivitz. This just makes sense.”

“There is zero chance in hell you will get my signature on anything. Won’t be able to get a Quit Claim. Not from Jakob either.”

Peter felt himself heating up. “Dammit, Nik, my back’s against the wall. Tina’s hands are full with our kid ’cause we can’t afford daycare and I’m on furlough. Again. I’m going to lose my family if we don’t do something.”

“Well,” Niklas said, “You and everybody else. This won’t put out the national economic dumpster fire.”

“Dude, I have bills. Selling Jussi’s place would pay a good number of them.”

“Sure,” said Niklas, growing vindictive, “But think about what you’d actually get. It’s not even worth selling. A third would barely cover two months of your life.”

Peter ignored the jab. “That’s not true. I bet we—”

“You.”

“Sure. I bet I could find a neighbor interested in splitting it up into lots or logging it or something. Who knows? But I’m pretty sure.”

“Look,” said Niklas, voice atremble, “I’ll huck it up there with you. I miss that place like hell. But we can’t sell it, you know that. Especially not without Jakob here to sign off. Again, not even sure about the whole Quit Claim thing.”

“Jakob would want me to be abl—”

“You don’t give a shit about what he would want.”

“That’s not fair.”

“Have you called him yet?” Nik demanded. “Written him a letter?”

“Come on, dude, I—”

“That’s what I thought.” Niklas was warming up. “So, what, you’re gonna call him up and say ‘Hey, Jakob, been a few years, mind if I rob you blind for the sake of bailing myself out?’ He’d be less insulted if we just sold the place and apologized to him afterward.”

“Well… so why don’t we do that?”

“You’re making a terrible case for yourself, Pete.”

“Nik, man, all I’m saying is come up with me. We don’t have to decide on anything,” Peter lied. “Just talk things over. Up there. Who knows, we might do all right if we find the right guy? We could leave aside a portion for a smaller lot somewhere, maybe.”

“Yeah,” Niklas said, “Go fuck yourself. Not a chance. That’s Uncle Jussi’s land. I wouldn’t take a million for my portion.”

Peter bit his tongue and waited. He knew Niklas wouldn’t be able to resist the trip north. Niklas had always been that way. “I’ll cover gas,” Peter added. A long moment passed.

“When do we leave?”

“Next Friday. That gives us two nights up there. All I’m saying is think it over. That’s all I’m saying.” Even though it wasn’t, and Peter knew it even as he said otherwise.

“I hear you,” Niklas said. “And I suspect you’re full of shit.”

“We could write Jakob a letter. Up there, around the fire, from both of us. He’d like that, wouldn’t he?”

“I just call him these days. He wrote me a few letters the first few months. I never wrote back because we just got to calling every few weeks.”

“Why didn’t you write back?”

“I don’t know. The letters were really intense. And we got to calling.”

“Do you still have the letters?” Peter asked.

“I carry them with me everywhere.”

“Geez, Nik.”

“Yeah, well. He’s up for parole in November.”

“Shit, really?”

“Yeah. My dad’s got his hopes up for a family Thanksgiving. I think he’s setting himself up for a letdown.”

“Huh. Well. Maybe we should write to him.”

“Maybe,” Nik sighed. “Sure.”

A moment passed. Peter hesitated. “Well, just swing by my place after work next Friday when you’re packed.”

“Yeah,” Niklas replied acidly. “Try to be ready when I come by, huh? I don’t want to sit in your ridiculous living room getting dirty looks from Tina about the sawdust on my clothes.”

“Oh, relax. I’ll be ready. You can toss the football with Olly, yeah? He loves that.”

Shamefully, this was a tactic, and the missing edge in Niklas’ voice as he responded said so. “Yeah, sure. How is the little stud? Last time I came by Tina was fussing over him asking if he felt up to playing, or needed his meds or something, I forget. He told me he hadn’t been to school in a week. He was real stoked about that, but, you know. He doing OK?”

Peter took a breath. “Yeah, he’s good. Just been a little under the weather and the doctors wanted to run some tests. The tests took him out of school for a few days.”

“Ah. Well. I hope the results are good. I’m sorry, dude.”

“Thanks.”

Silence hung, then broke with Niklas’ words.

“So we gotta call Chris, right? And Mike?” Peter cracked a smile on the other end of the phone.

“Sure, we’ll call Chris and Mike. I’m sure we’ll see that whole crew at Schmidt’s. Bonfire might happen too.” As Peter said so, he wondered if that one pretty bartender was still working at Schmidt’s. ”Nik, who was that bartender—”

“Hayley,” Nik said, answering before Peter finished.

“Damn right. Hopefully she’s still working.”

“Fingers crossed. Hopefully she remembers us.”

“I suppose she would remember Jakob best.”

Niklas laughed, a real full laugh this time. “I guess I should call Jim to open the cabin up. I think he’s got the keys. I can’t wait to see Jim.”

“Me neither. Good call, I’d forgotten he’s been keeping up the place.”

“Yeah. Wonder how he’s holding up.”

“Me too.” Peter looked out the window at a bird feasting on little mayflies gathered on the sill.

“Should I bring the bong?” Niklas asked. “Would that be disrespectful?”

“If you want,” Peter said. “That’s all you though.”

“Maybe I won’t. We never did when Uncle Jussi was around. Hmm. Yeah. I’ll just bring a bowl.”

“All right. I’ll have the bag.”

“Sounds good. When do we have to be back?”

“Monday for work, I figured.”

“Yeah, all right. Shit.” Both Niklas and Peter knew that this was the end of the call. The planning had begun. At the last second, Niklas spoke up again. His voice was soft, and there was a desperate edge. He sounded like he was about to throw a Hail Mary, and hoped Peter would be there to receive it.

“Say, Pete. Uh. You ever thought about, uh...?”

“About what?” Peter had no idea.

“Nothing. Never mind. I’ll see you Friday.”

2

The Beginning

As the story goes, pieced together with as little conjecture as possible in the mind of his grandson, Hannu, young Olli decided to leave Finland for Upper Michigan in the spring of 1901. He was excited at first but grew nervous as the date of his departure approached. Numerous as his friends were, he fretted all the last weeks up until his departure about his goodbyes. The longest-standing friendships of course deserved a goodbye dinner, a long house call, a parting gift. But what of the friends whose surnames he didn’t know, of the intimately familiar faces at this tavern or that inn, the lovely girls he’d danced with over long winter evenings? In the end he called on all of his close friends and said a prayer that his acquaintances would remember him fondly and take no offense at a noticeless departure.

The ship sailed from Hanko in June; the mood aboard was one of cautious optimism. Cramped together in the hold mere hours after departing, Olli got to talking to a few of those next to him and learned that his countrymen were a great deal more nervous for what awaited them on the other side of the Atlantic than he was. Going around the circle, more like a clump in the dark and musty hold each shared what they were leaving behind and why. When it was Olli’s turn, he shrugged.

“My mom says she don’t want me to be poor like we’ve been since grandfather. Her cousin has a son who got work in the copper mines. He wrote her these letters about the great forests, and the Indians, and it’s all snowy and near a great big sea of a lake. It sounded close enough to home. I thought it might be fun, or at least an adventure.”

An older man beside Olli roared with unkind laughter. “Well, son, perhaps your grandchildren will be happy. Or maybe their children will be. The mines will swallow you up if you’re not careful. You ought to be a little more desperate, like us. Gives you an edge. Keeps you honest.”

The man laughed at himself and Olli smiled back, wondering who was responsible for the axe handle up the guy’s ass.

Much later, after he’d worked in the mines for twenty-odd years, after acquiring a small farm, getting married, shepherding his children through school—after just about every one of his neighbors had caved to various pressures and purchased a car, after the doctors said his cholesterol would kill him if he didn’t ease up on the fried meat and potatoes—after all that, Olli Kinnunen’s kids and grandkids knew of only one subject that would raise his voice and the hairs on the back of his neck. That subject was strike-breakers, and it drew from Olli a venom and the suggestion of violence, which was strange and a little bit scary. By that time his belly was wide and round and he’d achieved the age where you no longer care if your reading glasses are crooked. He could talk to anybody, of any age. He joked with everybody, all the time. His grandkids remember stories about how he used to sing to the cows he took care of. During summer, he regularly and patiently opened windows and fanned blackflies from the living room back outside where they belonged. So it was strange that what seemed like old politics could still inspire rage over an unavenged transgression.

3

Friday, August 27, 2009 5:37 p.m.

There comes a time during summer in the Midwest when everyone sort of looks around and agrees that summer ought not to let the door hit its ass on the way out. A time of sweaty palms around the morning coffee, of bedsheets laundered thrice weekly, of hot pavement in the morning echoing with the meaty slap of flip-flops. A time of cold showers when even the rain won’t cool you off.

It had stopped raining when Niklas left his apartment on Milwaukee’s east side. The hot kind of rain, the kind that riles people up when it thickens the air and wafts upward from the concrete in an odor that might be pleasant if it ever came at a time when your underclothes were dry. At five in the afternoon the sun was well on its way back down, and the light came shallow from the west; the light was a haunting blend of yellow-amber, breaking through the pregnant clouds, somehow simultaneously dark and golden. Niklas nearly missed his bus drinking in the sky with closed eyes, his haste forgotten, head cocked as though photosynthesis were really possible if only you tried hard enough.

The hiss and sigh of the Green Line’s air brakes brought him back to earth. He slung a backpack over his left shoulder and his guitar case over his right. Three people got off the bus; one massively obese old woman with a walker, one flinty-eyed guy with a garbage bag full of empty cans, and an elderly lady who stopped to chat with the driver. Niklas waited for a moment on the concrete for the woman in front of him to finish. Once he’d fed two bills into the machine, his hands were empty but for a single soiled envelope stuffed with three letters. Filthy untied boot laces danced around the ankles of his paint-splattered jeans as he made for the rear of the bus. He took his blue backpack off and set it on the seat next to him, put the letters in the breast pocket of his damp t-shirt, and rested his guitar against his knees. He looked out the window and saw himself in the plexiglass. He was six feet tall and trim, with thin, straight blond hair that was shaggy around the ears, a thin, fuzzy beard, and perennially ratty clothes. His manner reminded people in some indirect way of a puppy.

Immediately after sitting he began to feel around and unzip his backpack to make sure he hadn’t forgotten anything: the hard cylindrical lump of his water bottle; a hardcover and a paperback, both novels; his knife, sharpened last week; a glass pipe, a cold metal grinder, a lighter, and a double zip-lock with a few grams of pot (procured from a coworker at the lumberyard, actually the same one who’d sharpened his knife); a few Clif bars; a phone charger; glasses that he sometimes wore, but usually not, preferring to just squint; his orange bottle of antidepressants. He sniffed the area of the bag where the pot was—barely a whiff, all clear. Once satisfied that everything was there, that what was forgotten was truly forgotten, he zipped everything up tight and took a deep breath.

Out the window, a decrepit Brady Street slid by. Torn awnings, unrepaired from the previous winter’s damage; patio tables and chairs that were fully occupied perhaps twice a week during this peak summer season; neon signs in the windows of the barrooms which were flickering or almost out of juice. Niklas wondered how much of this was normal Brady Street grittiness, and how much was actual damage done by the recession. An abandoned newspaper on the bus floor sat face up. The date read Friday August 27, 2009. Niklas took the letters out of his breast pocket and thumbed through them to make sure they were all there. He caught a glimpse of the corner of the last one. The date read March 2009. Niklas rubbed at a raised lump of dirt next to the return address on the envelope. He worked it long after it was obvious the spot wasn’t coming all the way out.

The bus driver chatted with a bent old man up front. Niklas couldn’t hear much beyond their tone, which was familiar. The bus driver had a thick Northwoods accent, which reminded him of old Jim Markham, their neighbor and friend over in Liminga, not five minutes from Uncle Jussi’s farm.

Niklas’ chest and gut clenched as he remembered what he’d forgotten—not an item, fortunately, but one of the most important things nonetheless. He flipped open his phone and found the name in his contacts. As the bus crawled down Brady Street the phone rang in his ear and his pulse quickened. He prayed he would say the right things.

“Hullo?”

“Jim! Niklas Kinnunen.”

“Nik! How are ya bud?”

“I’m real well, Jim,” he lied. “You holding up OK?”

“Oh yah, I’m fine.”

“Cynthia doing well?”

“Oh yah, she’s good. Wit da kids in town now. They’re having dinner at Gino’s.” The recorded bus voice announced Brady and Water Street, Niklas’ stop. He pulled the cord and cast around for a question that would buy him some time to get away from the noisy street corner.

“Any plans for the evening alone?”

“Oh no, I was just out back finishing da rafters on da extension. Going to a meeting with Randy in a while. He was supposed ta...” The bus pulled up and Niklas hopped off, laden with guitar and backpack. He walked quickly toward an alley to talk. The clouds had burned off. The afternoon was all the way golden now, casting crisp shadows on the pavement. In the cool shade, Niklas brought his attention back to the voice in his ear: “... hopefully gonna help me wit dose rafters and da ceiling. Could probably do ’em myself. Not da ceiling, though. One of you boys used to be da one holding up da plywood for me.”

“Well Jim, maybe we can come by and do some work with you. Peter and I are coming up tonight for the weekend. We’re really excited.”

“Oh! We weren’t sure you’d make it back before we croaked! Ha!”

“Could you—”

“You want me to open her up for ya?”

“Yes, please. Thank you, Jim.”

“I gotta remember where I put da key. I remember your dad gave it to me after da funeral… hmm. When are you guys gonna be here?”

“I’ll try and hustle Peter so… hopefully midnight?”

“Sure. I’ll open her up.”

“Thanks, Jim.”

“Oh, sure. You guys going to come by for a sauna?”

“Sure, we’ll help you with that ceiling, though, yeah?”

“Oh yah! That’s good.”

“Well, excellent. Thank you so much.”

“Oh, sure. See you soon.”

Niklas hung up and walked with the river on his right along Water Street toward Peter’s condo. He always felt like a rat in this part of town—paint on his jeans, sawdust in his hair, hands dirty, shoes torn—generally a zit on the otherwise unblemished sidewalks. The crowd today was either jogging after work or already refreshed and on their way to an overpriced dinner. Subtle spray tans and Ray-Bans and hair beat to submission with an iron along with regular dye jobs—the inhabitants of the Water Street condos that lined the river mystified Niklas with their cosmetic discipline. Just like the cars in their heated garages or the labels intentionally left on their clothes, it was all a carefully curated “dick-measuring contest,” as Jim used to say. But Peter had always been like that, or perhaps he’d merely aspired to that kind of crowd. It can be hard to make the distinction, and Niklas’ faith in his cousin was entirely reliant on the latter being true, though he wasn’t sure.

At the bottom of the short flight of steps leading to Peter’s building, a blond girl in a black Nike bra and spandex jogged past him breathing heavily up the steps. Niklas hesitated, then followed her straight into the lobby without buzzing up. He was reminded afresh that wealth and taste are often not on speaking terms; the tacky modern chrome and pastel of the lobby and elevator put Niklas in the mind of a fancy therapist’s office. He followed the jogger girl into the elevator.

“What floor?” she asked, after pressing three for herself.

“Four. Thanks.” She smiled at him with bright brown eyes. She reminded him of one of Jakob’s old girlfriends, a soccer player from California who’d cruelly left him in Chicago. Niklas felt a blush rising; he was relieved when the elevator arrived at the third floor, though he craned his neck to retain the view for as long as possible when she left.

He exhaled with relief when the elevator spat him out on the fourth floor into a world of chrome, except the carpet, which was a hideous orange patterned with abstract purple blocks trimmed in green. Peter’s place was about five doors down on the right, he could never remember exactly which. He overshot and had to double back a few doors when he heard the aggrieved voice of Peter’s wife, Tina, from behind one of them. After a second’s hesitation he knocked.

At first he couldn’t tell who had opened the door for him. A giggle escaped from down below. He looked down, and there was Peter’s seven-year-old son Olly in all his gap-toothed glory, smiling up at him as if to brandish his remarkable milk mustache.

“Heyyy buddy!” said Niklas.

“Hi Uncle Nik! Can you give me a piggyback ride?”

“Sure bud. Where to?”

“Pleaseeeee!!”

Niklas laughed and set down his bags and slung the kid up onto his shoulders. They walked down the hallway into the kitchen, where Tina and Peter were going back and forth in savage whispers that weren’t very quiet at all. They looked up in unison as Nik and the boy came in, eyes like some insolent puppies’ who’d been caught raiding the cupboard. Tina, though rail thin and only five feet tall, had the commanding presence of a football coach. Her dark hair swung across her face as she took in the situation, and her expression twisted with outrage.

“Hello Niklas. Put him down, please.” She wheeled on Peter. “What’s going on?”

Peter tried to smile in Nik’s direction, and grimaced. He wore a t-shirt and khaki pants, his dirty blond hair cropped short and face patchy from a few days without a shave. His face was more angular, eyes more restless, though he was about the same height as Niklas. If you looked at their faces together, you would be certain that Niklas was the more generous, patient, earnest, gullible. Peter’s eyes were flighty and suspicious, his nose sharp, while Niklas’ steady, upturned visage and rounded nose put people at ease. He nodded shiftily at Nik. “Hey, bud. Aren’t you a little early?”

“Dude, you said six. It’s, like, quarter of. Please tell me you’ve packed.”

Tina looked like she was about to blow a gasket. “Packed? Packed, Peter? Packed for what?”

“Sweetie, Nik and I—”

“Don’t ‘sweetie’ me!” She seemed to suddenly wake up to the fact that Olly was in the room. She marched over to him and corralled him by the shoulders into his room. In a moment she reappeared, eyes shining with rage.

“Peter, tell me you’ll be here tomorrow for Olly’s appointment.”

Peter blanched. “I thought it was next week. That’s what you said last week, right?”

“Yes! Yes I did. Last week I said it was next weekend, which makes it this one!”

Niklas raised an eyebrow at Peter. Peter looked at his feet for a while then gingerly met his wife’s eye. “Christina, I know you want me there. But if we have to go through with… with things, we’re gonna need more funds than we have. Nik and I have some family business up on the Keweenaw this weekend that should lighten the load significantly. Please trust me on this.”

Tina was shaking her head, nearly mute. She started several quick sentences without finishing them. When she finally got a grip on language, she spoke slowly, her gaze shifting from one to the other of the men. Tears leaked from the corners of her eyes and her voice was wobbly.

“I know better than to ask you two not to do this, if your minds are made up. Peter, you promised about tomorrow. I’ll spare Niklas the scene but I can’t believe you’re hanging me, hanging us, out to dry like this. I hope you guys get whatever you want up there.” And she marched out the door.

“What we want, hon—” Peter started to say, but then their bedroom door slammed and he and Niklas were alone. He took a couple of breaths and looked around to get his bearings. “All right Nik, why don’t you take a lap and I’ll pack a ditty bag. I’ll be ready in fifteen minutes.” The term ‘ditty bag’ gave Niklas a start. It was one of his dad’s, instead of ‘duffel bag’. He hadn’t heard it in years and it tugged at his heart.

“OK, hustle up then,” Niklas said. “We’re burning daylight and I told Jim that we’d be there by midnight. He’s going to open up the cabin for us.”

“All right. I’ll be glad to see Jim.”

“So will I, so hustle up. I’ll be back in fifteen.” Niklas left Peter to pack a bag and salvage what goodwill he could with his wife before hitting the road. He strode toward the elevator as Tina’s strained, pleading voice once again floated out into the hallway.

* * *

On his way out of the lobby, Niklas passed a beanpole skinny boy in ripped jeans and heavy makeup with a beautiful black lab puppy on a leash. The puppy bounded up to him; he sank down to receive and return the embrace.

“His name’s Baxter,” the boy said. Baxter slobbered all over Niklas hands and face. His owner smiled faintly. Niklas had made a habit of spending extra affection on dogs ever since his own childhood dog, Poppy, had died unexpectedly—the memory of her face out the living room window as he’d left the house as a child had haunted him terribly. She’d died in the summer when he was eleven, just before Peter’s family left for New York.

The day Poppy died, the boys were camped at their spot down by the creek, about a ten-minute walk along the creek through the woods from Uncle Jussi’s cabin. Niklas and Jakob’s father, Hannu, was home in Marquette at a conference. They’d been camping for four days, and hoped to stay another three nights, helping their Uncle Jussi mend a section of the orchard fence and weed the lingonberry patch which Hannu had planted in honor of his wife’s Swedish heritage, and pick turnips when they weren’t off on some adventure. A few of the tart red pellet-sized berries were visible on the bushes already. On the fifth morning, Niklas rose at sunrise to soothe his parched lips and take a shit. The clouds were dark and fat with rain, the air thick with moisture. Jakob and Peter were awake by the time he got back. They decided to play euchre in the tent for a while on account of the weather, but gave it up because Niklas insisted on Jakob as a partner and Peter didn’t want to walk all the way to the cabin to ask Uncle Jussi to play with them. They drifted off for about an hour and then Uncle Jussi came tumbling out of the woods, unzipped the tent, jostled their shoulders and insisted they rouse themselves.

Jussi barely met their eyes all throughout his story. Their sweet dog. Poppy, was dead. Her illness was not entirely clear and completely beside the point. She’d been healthy one night, slow the next, then immobile, and finally dead four nights after she first fell ill. She was tender and skittish, fiercely loyal and slow to become so; people loved her extra, once they got to know her.

Jakob lost it and sprinted from the campsite with Niklas on his heels. Jakob drove ninety the whole way back to Marquette from Atlantic Mine. Their father, Hannu, was rocking Pernilla, their mother, but his beard was damp with sweat and tears. Poppy was wrapped in her favorite quilt on the back porch. Fistfuls of lilacs sat atop the crest in the blanket that must have been over the dog’s heart. Jakob threw himself down beside her and wept. Niklas went back inside and tactlessly grilled his parents about her final hours. Had she been comfortable? Did they feed her the carrot heavy chicken and rice dish that was her unlikely favorite? Had she any final messages for them, however flimsy the conjecture surrounding the message might be?

The answer to the first two questions was “Of course” and his mom started to answer the third, “but a fresh salvo of tears silenced her. His dad finished what his mom had started. On Poppy’s last night, after an hour of vomiting and quiet whimpers she was doped up on pain meds from the vet. Just before she dropped off to sleep in the front room below her favorite window, two neighborhood tabbies she’d grown friendly with came crying to the front door. When she didn’t leap up and bound over to bark her greeting, the cats’ cries persisted and increased in volume. Pernilla let the cats in for the first time ever. They slowly walked up to the old dog who raised her head slightly, fighting the meds. Each cat in turn stepped gave her a nuzzle and left the house with their heads bowed, tails stiff in mourning. Pernilla went to stroke Poppy. The dog let out one last feeble bark, licked her outstretched hand, and died.

Two years later, Niklas’ buddy, Drake from high school, went to jail for selling meth. His dog, Berkeley, had finally succumbed to some long festering illness and Gwen, Drake’s mom, called Niklas up one day and asked if he could come spread Berkeley’s ashes with her, since she didn’t have anyone else. Drake was in jail, her other sons were out of town. Niklas readily agreed. It was a wretched day all around with the most fabulous weather. They parked and walked all the way out to the end of Presque Isle and spread Berkeley’s ashes under a massive spruce tree near the water.

Niklas was stroking Baxter’s head, lost in memory, when the skinny guy’s voice brought him back to earth. He had to eat dinner, he said, and then he had to rush out to a drag show. Just as quickly as Niklas had forgotten the warring family he’d left upstairs, as quickly as the guy and his dog had appeared, so quickly did the elevator swallow them up. Alone again, Niklas walked outside for a lap around the block to wait for Peter, fingers crossed for the advent of other dogs.

He was sitting on the curb lost in thought when Peter called. He’d been watching three ants coordinate the dragging of crumbs from a half-eaten roast beef sandwich that was rotting on the sidewalk. The lead ant paused, and Niklas brought down a fingernail, severing the ant’s head from its thorax. A fellow ant came along and began dragging his buddy along, minus a head. Niklas wondered whether he was being dragged to safety or added to the food supply, and a wave of remorse passed over him just as Peter called to summon him back upstairs.

Tina answered the door. She was sniffling, and she spoke to the floor in barely a whisper: “Please be safe. Call me if anything happens. Watch out for deer, and please get him home in a few days. It’s always the second deer, you know. The one that jumps out after you think you’ve dodged the first one.” She paced quickly into the apartment and disappeared down the hallway to the bedroom.

Peter stood in the kitchen with a backpack and a ditty bag at his feet, wiping a tumbler at the sink. He turned around and looked at Niklas with wild eyes. After a second the flames died, and he seemed to realize what was happening. “Give me a second,” he said. “Bathroom.” He set the glass upside down in a cabinet above the sink and disappeared.

Niklas waited on the couch, tapping his foot on the living room carpet. He had to knock twice to get Peter out of the bathroom, and when he finally opened up he was all ready to go (Niklas heard no flush), stumbling over himself to get out of Niklas’ way. He grabbed his bags and the two boys took off out the door.

* * *

They headed north on I-43, the sun blasting in from their left, the fields of farmland north of Sheboygan glowing in the late afternoon sun. Farmhouse roofs, the domes atop silos, little bits of machinery strewn about all caught bits of the setting sun and flashed at the cars that whizzed by. The hills began to undulate gently; the trees beside the road were still mostly hardwoods, and the brush was firm-soiled and not yet bogged with swamps. Niklas ached for the last three hours of the drive on the two-lane way through the swampy foothills and forest of the Upper Peninsula, and especially for the last hour; the first sight of Lake Superior coming down and around Keweenaw Bay was always triumphant.

Peter had remained silent for the first twenty minutes but warmed to conversation as the familiar road passed beneath their wheels. The country seemed to loosen his tongue. Niklas treaded carefully, unsure of Peter’s exact state of mind. He was eager to keep Peter in a good mood and tingling with anticipation at this first adventure in quite a while. They lingered on the subject of fantasy football, though only Peter was actually playing this year.

“You want to huck it the Big House this fall?” Niklas asked, hopeful. “I got a buddy from Chicago that invited me for the Wisconsin game in September.”

“I wish,” Peter said. “Tina gave me a really hard time after the debacle at the Northwestern game. Even my dad heard about it all the way in New York.”

Niklas suppressed a laugh, but the memory was a sad one too. “I still feel bad about that. I remember I’d forgotten at the time you had a kid. Jakob reminded me like six hours into the drive north after the game.” A burst of laughter. “And that motel room in Dunbar! With the heart shaped hot tub. I remember losing my mind ‘cause I thought the wallpaper was moving like a bunch of vines to swallow me up.”

Peter cracked a smile. “When I think about that weekend I can remember most of it, but not why. Why did I think it was a good idea to drive to Jussi’s place after a football game. After the game it all just…”

“Went insane, like, to a different dimension. I can’t believe we’re nostalgic about it now. I remember sitting in the motel parking lot in Dunbar at like four in the morning, coming down, thinking, Shit, not only am I gonna be sober tomorrow, we’re all way too beat to make it to Uncle Jussi’s. I legit cried at the thought of work on Monday.”

“We were so close,” Peter said, with uncharacteristic wistfulness. “We almost made it. I remember, I was pissed when you guys woke me up outside the motel.”

“I tried so hard to keep Jakob driving. We were about to hit that stretch after Crystal Falls where it’s like a hundred miles without any real place to stop. He’d been hitting rumble strips for half an hour. He was probably right to stop, but I was still high enough to pull hard for the alternative.”

Outside, the rim of the sky began to turn pink, and the rumpled hills grew slightly less shallow. Niklas zipped open the pack at his feet and made sure the envelope with Jakob’s letters was safe and uncrumpled. Peter gazed with glazed eyes sightlessly out the window.

“Man,” he said. “I guess that really was the last time I was up. Three years ago, almost.”

“Three years. Forever ago, and nearer than yesterday.”

“You went up last Christmas though, right?” Peter asked.

“Yeah. No, two Christmases ago. This last one I was in Marquette.”

“Ah, right. It was right after the funeral you went up though, right?”

“Sort of. A few months later.” Niklas paused. “Jakob had just, you know, gotten in trouble.”

“Right, yeah. The Northwestern game was in September, and Jakob’s trial was over in, what, November?”

“Yeah. It was after that I went up to the farm with Dad. It was right after I got out of the hospital, actually. I was in for ten days, right after the trial. Dad thought I needed a sort of halfway house situation, or at least company, when they let me out.”

“You were moving to Milwaukee around then, I remember,” Peter said. “You came over for dinner a few times that winter. Olly loved it.”

“Yeah. And Dad just called me one day in mid-December and picked me up and we just drove north. I think he was going through it to, you know—of course he was. We kind of cleaned up the cabin and collected Uncle Jussi’s stuff into boxes. Dad drank more than I ever saw him drink, and at night we played the guitar and sang around the fire even when it snowed. Music was the only thing that helped Dad’s mood. It felt so weird being there, knowing the land was ours and not his anymore. He said he’s glad for that, that he wouldn’t know what to do with the place without Uncle Jussi. It still feels weird to me, and even weirder that we three never stood together on the land that’s now ours. We found some awesome bits and pieces cleaning out the cabin, though. This old skinning knife that I got sharpened on the way home. I can’t find it now. It’s really bumming me out.”

Peter nodded. Niklas grew sentimental about almost everything, which made their current predicament that much more fraught, though to Peter, Nik didn’t really appear to have processed it yet, or perhaps hadn’t taken him seriously on the phone.

“I’m sure you’ll find it,” Peter said. “You take it home?”

“No, it’s in Marquette. I think it is, at least.”

“Huh.” Peter had the cruise control set at seventy-six. They passed cars steadily as the sun sunk low into the western sky. Their long shadow flew across the gravel and brush ditches beside the highway. The asphalt of the road looked a bloody beige, the fields and roadside brush a rich amber-green.

“The smokestack, too,” Niklas said, in the middle of a thought.

“What?”

“We got to go by the smokestack out in Freda. You know, the old crushing plant, right on the lake?”

“I think that was mostly you and Jakob. I was gone by then.”

“No, you came out with us a couple of times.”

Peter squinted. “Maybe.”

“It’s just a massive stretch of concrete ruins. Dad told me that Grandpa Teemu worked there with Jim’s father. They were both on the crusher. You remember that giant circle in the concrete? Some of the infrastructure is still intact. We’d always climb up into the old smokestack by the lake and make fires. You could see stars out the top at night. You could walk out a hundred yards onto Superior in the winter. The ice froze in these massive mounds. Some of them were caves. We gotta go,” he said again. Peter stared straight ahead, stone-faced. Niklas wondered at his ill temper. It was something more than stress at his own situation—beneath the surface, Niklas could smell resentment.

“I need a piss,” Peter suddenly announced. “Cool if we stop soon?”

“We been on the road barely an hour.” Niklas was champing at the bit, annoyed at this interruption.

“I’m just hydrated.”

“Bullshit,” spat Nik.

“Come on.”

“We just got on the road. I want to hustle up there. Let’s wait till we switch drivers.”

“OK, but I actually need to piss. Please.”

Niklas felt a surge of suspicion. Peter usually just went ahead and did things. There was something vulnerable in his Please.

“Fine. You gotta cover gas though.”

“All right.”

Once again, Niklas was surprised at the lack of protest. He forgot about it as they passed a sign announcing Green Bay in twenty-nine miles. To the east the sky was a deep indigo, which paled around the silhouettes of trees on the horizon. In a few minutes Peter pulled off the highway and made for a Kwik Trip.

Niklas bit his tongue in frustration as Peter pulled into a parking spot instead of beside a pump. He leapt out right away and Niklas watched him make a beeline for the bathroom. He followed Peter inside, stretching his legs on the way in, and grabbed a chocolate milk and a thing of chicken tenders. On the way out the door, it occurred to Niklas it’d be late by the time they got up north. He turned back and got a case of Miller and a fifth of Kessler, and a box of oatmeal raisin cookies for Jim—his favorite. His father had always impressed upon him the duty of never arriving anywhere empty-handed, and indeed many a time had brought these exact cookies for Jim.

Outside, Niklas leaned on Peter’s car using the roof as a table, wolfing his tenders. He watched blue-jeaned men stop to fill up and stock up after a day’s work, their shirts and hands dirty, their boots creased, hunger and thirst in their eyes. As Niklas finished his chocolate milk, he watched a family of five negotiate the rearrangement of a tightly packed pickup. Peter had been in the bathroom for fifteen minutes. Niklas decided to go check on him.

The girl behind the counter was whispering something to an older lady in an apron. Both were looking at the bathroom. Niklas’ heart sank. He headed through the aisles and looked around before he opened the bathroom door, hoping it was someone else being whispered about in nervous tones.

Peter was leaning over the sink. Blood was streaming from his nose past the already drenched wad of tissue in his hands. He was so preoccupied, he failed to look up when Niklas entered, rushed up, and patted his back.