Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

"The Life Of George Washington" is a monumental work on the life of one of the most famous American presidents. Originally published in five volumes between 1853 and 1859, it is a treasure chest of information on Washington and the Civil War. This work is presumeably the most intimate and fascinating biography of a man who worked his way from an Army commander to the first President of the United States. This is volume five out of five.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 516

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Life Of Gorge Washington, Vol. 5

Washington Irving

Contents:

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 5

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

Chapter XVI.

Chapter XVII.

Chapter XVIII.

Chapter XIX.

Chapter XX.

Chapter XXI.

Chapter XXII.

Chapter XXIII.

Chapter XXIV.

Chapter XXV.

Chapter XXVI.

Chapter XXVII.

Chapter XXVIII.

Chapter XXIX.

Chapter XXX.

Chapter XXXI.

Chapter XXXII.

Chapter XXXIII.

Chapter XXXIV.

Appendix.

Portraits Of Washington.

Washington's Farewell Address.

Washington's Will.

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 5, W. Irving

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN: 9783849642204

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

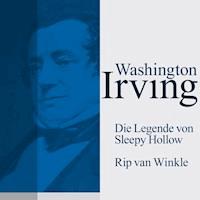

Washington Irving – A Biographical Primer

Washington Irving (1783-1859), American man of letters, was born at New York on the 3rd of April 1783. Both his parents were immigrants from Great Britain, his father, originally an officer in the merchant service, but at the time of Irving's birth a considerable merchant, having come from the Orkneys, and his mother from Falmouth. Irving was intended for the legal profession, but his studies were interrupted by an illness necessitating a voyage to Europe, in the course of which he proceeded as far as Rome, and made the acquaintance of Washington Allston. He was called to the bar upon his return, but made little effort to practice, preferring to amuse himself with literary ventures. The first of these of any importance, a satirical miscellany entitled Salmagundi, or the Whim-Whams andOpinions of Launcelot Langstaff and others, written in conjunction with his brother William and J. K. Paulding, gave ample proof of his talents as a humorist. These were still more conspicuously displayed in his next attempt, A History of New York from theBeginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by “Diedrich Knickerbocker” (2 vols., New York, 1809). The satire of Salmagundi had been principally local, and the original design of “Knickerbocker's” History was only to burlesque a pretentious disquisition on the history of the city in a guidebook by Dr Samuel Mitchell. The idea expanded as Irving proceeded, and he ended by not merely satirizing the pedantry of local antiquaries, but by creating a distinct literary type out of the solid Dutch burgher whose phlegm had long been an object of ridicule to the mercurial Americans. Though far from the most finished of Irving's productions, “Knickerbocker” manifests the most original power, and is the most genuinely national in its quaintness and drollery. The very tardiness and prolixity of the story are skillfully made to heighten the humorous effect.

Upon the death of his father, Irving had become a sleeping partner in his brother's commercial house, a branch of which was established at Liverpool. This, combined with the restoration of peace, induced him to visit England in 1815, when he found the stability of the firm seriously compromised. After some years of ineffectual struggle it became bankrupt. This misfortune compelled Irving to resume his pen as a means of subsistence. His reputation had preceded him to England, and the curiosity naturally excited by the then unwonted apparition of a successful American author procured him admission into the highest literary circles, where his popularity was ensured by his amiable temper and polished manners. As an American, moreover, he stood aloof from the political and literary disputes which then divided England. Campbell, Jeffrey, Moore, Scott, were counted among his friends, and the last-named zealously recommended him to the publisher Murray, who, after at first refusing, consented (1820) to bring out The Sketch Book ofGeoffrey Crayon, Gent. (7 pts., New York, 1819-1820). The most interesting part of this work is the description of an English Christmas, which displays a delicate humor not unworthy of the writer's evident model Addison. Some stories and sketches on American themes contribute to give it variety; of these Rip van Winkle is the most remarkable. It speedily obtained the greatest success on both sides of the Atlantic. Bracebridge Hall, or the Humourists (2 vols., New York), a work purely English in subject, followed in 1822, and showed to what account the American observer had turned his experience of English country life. The humor is, nevertheless, much more English than American. Tales of a Traveller (4 pts.) appeared in 1824 at Philadelphia, and Irving, now in comfortable circumstances, determined to enlarge his sphere of observation by a journey on the continent. After a long course of travel he settled down at Madrid in the house of the American consul Rich. His intention at the time was to translate the Coleccionde los Viajes y Descubrimientos (Madrid, 1825-1837) of Martin Fernandez de Navarrete; finding, however, that this was rather a collection of valuable materials than a systematic biography, he determined to compose a biography of his own by its assistance, supplemented by independent researches in the Spanish archives. His History of the Life and Voyages ofChristopher Columbus (London, 4 vols.) appeared in 1828, and obtained a merited success. The Voyages and Discoveries ofthe Companions of Columbus (Philadelphia, 1831) followed; and a prolonged residence in the south of Spain gave Irving materials for two highly picturesque books, A Chronicle of theConquest of Granada from the MSS. of [an imaginary] FrayAntonio Agapida (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1829), and The Alhambra:a series of tales and sketches of the Moors and Spaniards (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1832). Previous to their appearance he had been appointed secretary to the embassy at London, an office as purely complimentary to his literary ability as the legal degree which he about the same time received from the university of Oxford.

Returning to the United States in 1832, after seventeen years' absence, he found his name a household word, and himself universally honored as the first American who had won for his country recognition on equal terms in the literary republic. After the rush of fêtes and public compliments had subsided, he undertook a tour in the western prairies, and returning to the neighborhood of New York built for himself a delightful retreat on the Hudson, to which he gave the name of “Sunnyside.” His acquaintance with the New York millionaire John Jacob Astor prompted his next important work — Astoria (2 vols., Philadelphia, 1836), a history of the fur-trading settlement founded by Astor in Oregon, deduced with singular literary ability from dry commercial records, and, without labored attempts at word-painting, evincing a remarkable faculty for bringing scenes and incidents vividly before the eye. TheAdventures of Captain Bonneville (London and Philadelphia, 1837), based upon the unpublished memoirs of a veteran explorer, was another work of the same class. In 1842 Irving was appointed ambassador to Spain. He spent four years in the country, without this time turning his residence to literary account; and it was not until two years after his return that Forster's life of Goldsmith, by reminding him of a slight essay of his own which he now thought too imperfect by comparison to be included among his collected writings, stimulated him to the production of his Life of Oliver Goldsmith, with Selections fromhis Writings (2 vols., New York, 1849). Without pretensions to original research, the book displays an admirable talent for employing existing material to the best effect. The same may be said of The Lives of Mahomet and his Successors (New York, 2 vols., 1840-1850). Here as elsewhere Irving correctly discriminated the biographer's province from the historian's, and leaving the philosophical investigation of cause and effect to writers of Gibbon's caliber, applied himself to represent the picturesque features of the age as embodied in the actions and utterances of its most characteristic representatives. His last days were devoted to his Life of George Washington (5 vols., 1855-1859, New York and London), undertaken in an enthusiastic spirit, but which the author found exhausting and his readers tame. His genius required a more poetical theme, and indeed the biographer of Washington must be at least a potential soldier and statesman. Irving just lived to complete this work, dying of heart disease at Sunnyside, on the 28th of November 1859.

Although one of the chief ornaments of American literature, Irving is not characteristically American. But he is one of the few authors of his period who really manifest traces of a vein of national peculiarity which might under other circumstances have been productive. “Knickerbocker's” History of NewYork, although the air of mock solemnity which constitutes the staple of its humor is peculiar to no literature, manifests nevertheless a power of reproducing a distinct national type. Had circumstances taken Irving to the West, and placed him amid a society teeming with quaint and genial eccentricity, he might possibly have been the first Western humorist, and his humor might have gained in depth and richness. In England, on the other hand, everything encouraged his natural fastidiousness; he became a refined writer, but by no means a robust one. His biographies bear the stamp of genuine artistic intelligence, equally remote from compilation and disquisition. In execution they are almost faultless; the narrative is easy, the style pellucid, and the writer's judgment nearly always in accordance with the general verdict of history. Without ostentation or affectation, he was exquisite in all things, a mirror of loyalty, courtesy and good taste in all his literary connexions, and exemplary in all the relations of domestic life. He never married, remaining true to the memory of an early attachment blighted by death.

The principal edition of Irving' s works is the “Geoffrey Crayon,” published at New York in 1880 in 26 vols. His Life and Letters was published by his nephew Pierre M. Irving (London, 1862-1864, 4 vols.; German abridgment by Adolf Laun, Berlin, 1870, 2 vols.) There is a good deal of miscellaneous information in a compilation entitled Irvingiana (New York, 1860); and W. C. Bryant's memorial oration, though somewhat too uniformly laudatory, may be consulted with advantage. It was republished in Studies of Irvine (1880) along with C. Dudley Warner's introduction to the “Geoffrey Crayon” edition, and Mr. G. P. Putnam's personal reminiscences of Irving, which originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. See also Washington Irving (1881), by C. D. Warner, in the “American Men of Letters” series; H. R. Haweis, American Humourists (London, 1883).

The Life Of George Washington, Vol. 5

Chapter I.

The eyes of the world were upon Washington at the commencement of his administration. He had won laurels in the field; would they continue to flourish in the cabinet? His position was surrounded by difficulties. Inexperienced in the duties of civil administration, he was to inaugurate a new and untried system of government, composed of States and people, as yet a mere experiment, to which some looked forward with buoyant confidence, — many with doubt and apprehension.

Hs had moreover a high-spirited people to manage, in whom a jealous passion for freedom and independence had been strengthened by war, and who might bear with impatience even the restraints of self-imposed government. The Constitution which he was to inaugurate had met with vehement opposition, when under discussion in the General and State governments. Only three States, New Jersey, Delaware, and Georgia, had accepted it unanimously. Several of the most important States had adopted it by a mere majority; five of them under an expressed expectation of specified amendments or modifications; while two States, Rhode Island and North Carolina, still stood aloof.

It is true, the irritation produced by the conflict or opinions in the general and State conventions, had, in a great measure subsided; but circumstances might occur to inflame it anew. A diversity of opinions still existed concerning the new government. Some feared that it would have too little control over the individual States: that the political connection would prove too weak to preserve order and prevent civil strife; others, that it would be too strong for their separate independence, and would tend toward consolidation and despotism.

The very extent of the country he was called upon to govern, ten times larger than that of any previous republic, must have pressed with weight upon Washington's mind. It presented to the Atlantic a front of fifteen hundred miles, divided into individual States, differing in the forms of their local governments, differing from each other in interests, in territorial magnitudes, in amount of population, in manners, soils, climates and productions, and the characteristics of their several peoples.

Beyond the Alleghenies extended regions almost boundless, as yet for the most part wild and uncultivated, the asylum of roving Indians and restless, discontented white men. Vast tracts, however, were rapidly being peopled, and would soon be portioned into sections requiring local governments. The great natural outlet for the exportation of the products of this region of inexhaustible fertility, was the Mississippi; but Spain opposed a barrier to the free navigation of this river. Here was peculiar cause of solicitude. Before leaving Mount Vernon, Washington had heard that the hardy yeomanry of the far West were becoming impatient of this barrier, and indignant at the apparent indifference of Congress to their prayers for its removal. He had heard, moreover, that British emissaries were fostering these discontents, sowing the seeds of disaffection, and offering assistance to the Western people to seize on the city of New Orleans and fortify the mouth of the Mississippi; while, on the other hand, the Spanish authorities at New Orleans were represented as intriguing to effect a separation of the Western territory from the Union, with a view or hope of attaching it to the dominion of Spain.

Great Britain, too, was giving grounds for territorial solicitude in these distant quarters by retaining possession of the Western posts, the surrender of which had been stipulated by treaty. Her plea was, that debts due to British subjects, for which by the same treaty the United States were bound, remained unpaid. This the Americans alleged was a mere pretext: the real object of their retention being the monopoly of the fur trade; and to the mischievous influence exercised by these posts over the Indian tribes, was attributed much of the hostile disposition manifested by the latter along the Western frontier.

While these brooding causes of anxiety existed at home, the foreign commerce of the Union was on a most unsatisfactory footing, and required prompt and thorough attention. It was subject to maraud, even by the corsairs of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, who captured American merchant vessels and carried their crews into slavery; no treaty having yet been made with any of the Barbary powers excepting Morocco.

To complete the perplexities which beset the new government, the finances of the country were in a lamentable state. There was no money in the treasury. The efforts of the former government to pay or fund its debts, had failed; there was a universal state of indebtedness, foreign and domestic, and public credit was prostrate.

Such was the condition of affairs when Washington entered upon his new field of action. He was painfully aware of the difficulties and dangers of an undertaking in which past history and past experience afforded no precedents. "I walk, as it were, on untrodden ground, " said he; " so many untoward circumstances may intervene in such a new and critical situation, that I shall feel an insuperable diffidence in my own abilities. I feel, in the execution of my arduous office, how much I shall stand in need of the countenance and aid of every friend to myself, of every friend to the Revolution, and of every lover of good government."

As yet he was without the support of constitutional advisers, the departments under the new government not being organized; he could turn with confidence, however, for counsel in an emergency to John Jay, who still remained at the head of affairs, where he had been placed in 1784. He was sure of sympathy also in his old comrade, General Knox, who continued to officiate as Secretary of War; while the affairs of the treasury were managed by a board, consisting of Samuel Osgood, Walter Livingston, and Arthur Lee. Among the personal friends not in office, to whom Washington felt that he could safely have recourse for aid in initiating the new government, was Alexander Hamilton. It is true, many had their doubts of his sincere adhesion to it. In the Convention in Philadelphia, he had held up the British Constitution as a model to be approached as nearly as possible, by blending some of the advantages of monarchy with the republican form. The form finally adopted was too low-toned for him: he feared it might prove feeble and inefficient; but he voted for it as the best attainable, advocated it in the State Convention in New York, and in a series of essays, collectively known as "The Federalist," written conjunctively with Madison and Jay; and it was mainly through his efforts as a speaker and a writer that the Constitution was ultimately accepted. Still many considered him at heart a monarchist, and suspected him of being secretly bent upon bringing the existing government to the monarchical form. In this they did him injustice. He still continued, it is true, to doubt whether the republican theory would admit of a vigorous execution of the laws, but was clear that it ought to be adhered to as long as there was any chance for its success. " The idea of a perfect equality of political rights among the citizens, exclusive of all permanent or hereditary distinctions," had not hitherto, he thought, from an imperfect structure of the government, had a fair trial, and " was of a nature to engage the good wishes of every good man, whatever might be his theoretic doubts;" the endeavor, therefore, in his opinion, ought to be to give it "a better chance of success by a government more capable of energy and order."

Washington, who knew and appreciated Hamilton's character, had implicit confidence in his sincerity, and felt assured that he would loyally aid in carrying into effect the Constitution as adopted.

It was a great satisfaction to Washington, on looking round for reliable advisers at this moment, to see James Madison among the members of Congress; Madison, who had been with him in the convention, who had labored in the "Federalist," and whose talents as a speaker, and calm, dispassionate reasoner, whose extensive information and legislative experience, destined him to be a leader in the House. Highly appreciating his intellectual and moral worth, "Washington would often turn to him for counsel. "I am troublesome," would he say, " but you must excuse me; ascribe it to friendship and confidence."

Knox, of whose sure sympathies we have spoken, was in strong contrast with the cool statesman just mentioned. His mind was ardent and active, his imagination vivid, as was his language. He had abandoned the military garb, but still maintained his soldier-like air. He was large in person, above the middle stature, with a full face, radiant and benignant, bespeaking his open, buoyant, generous nature. He had a sonorous voice, and sometimes talked rather grandly, flourishing his cane to give effect to his periods. He was cordially appreciated by Washington, who had experienced his prompt and efficient talent in time of war, had considered him one of the ablest officers of the Revolution, and. now looked to him as an energetic man of business, capable of giving practical advice in time of peace, and cherished for him that strong feeling of ancient companionship in toil and danger, which bound the veterans of the Revolution firmly to each other.

Chapter II.

THE moment the inauguration was over Washington was made to perceive that he was no longer master of himself or of his home. " By the time I had done breakfast," writes he, " and thence till dinner, and afterwards till bed-time, I could not get rid of the ceremony of one visit before I had to attend to another. In a word, I had no leisure to read or to answer the dispatches that were pouring in upon me from all quarters."

How was he to be protected from these intrusions? In his former capacity as commander-in-chief of the armies, his head-quarters had been guarded by sentinels and military etiquette; but what was to guard the privacy of a popular chief magistrate?

What, too, were to be the forms and ceremonials to be adopted in the presidential mansion, that would maintain the dignity of his station, allow him time for the performance of its official duties, and yet be in harmony with the temper and feelings of the people, and the prevalent notions of equality and republican simplicity?

The conflict of opinions that had already occurred as to the form and title by which the President was to be addressed, had made him aware that every step at the outset of his career would be subject to scrutiny, perhaps cavil, and might hereafter be cited as a precedent. Looking round, therefore, upon the able men at hand, such as Adams, Hamilton, Jay, Madison, he propounded to them a series of questions as to a line of conduct proper for him to observe.

In regard to visitors, for instance, would not one day in the week be sufficient for visits of compliment, and one hour every morning (at eight o'clock for example) for visits on business?

Might he make social visits to acquaintances and public characters, not as President, but as private individual? And then as to his table — under the preceding form of government, the Presidents of Congress had been accustomed to give dinners twice a week to large parties of both sexes, and invitations had been so indiscriminate, that every one who could get introduced to the President conceived he had a right to be invited to his board. The table was, therefore, always crowded with a mixed company; yet, as it was in the nature of things impracticable to invite everybody, as many offenses were given as if no table bad been kept.

Washington was resolved not to give general entertainments of this kind, but in his series of questions be asked whether he might not invite, informally or otherwise, six, eight, or ten official characters, including in rotation the members of both Houses of Congress, to dine with him on the days fixed for receiving company, without exciting clamors in the rest of the community.

Adams in his reply talked of chamberlains, aides-decamp, masters of ceremony, and evinced a high idea of the presidential office, and the state with which it ought to be maintained. "The office," writes he, "by its legal authority defined in the Constitution, has no equal in the world excepting those only which are held by crowned heads; nor is the royal authority in all cases to be compared to it. The royal office in Poland is a mere shadow in comparison with it. The Dogeship in Venice, and the Stadtholdership in Holland, are not so much — neither dignity nor authority can be supported in human minds, collected into nations or any great numbers, without a splendor and majesty in some degree proportioned to them. The sending and receiving ambassadors is one of the most splendid and important prerogatives of sovereigns, absolute or limited, and this in our Constitution is wholly in the President. If the state and pomp essential to this great department are not in a good degree preserved, it will be in vain for America to hope for consideration with foreign powers."

According to Mr. Adams, two days in a week would be required for the receipt of visits of compliment. Persons desiring an interview with the President should make application through the minister of state. In every case the name, quality or business of the visitor should be communicated to a chamberlain or gentleman in waiting, who should judge whom to admit, and whom to exclude. The time for receiving visits ought to be limited, as for example, from eight to nine or ten o'clock, lest the whole morning be taken up. The President might invite what official character, members of Congress, strangers, or citizens of distinction he pleased, in small parties without exciting clamors; but this should always be done without formality. His private life should be at his own discretion, as to giving or receiving informal visits among friends and acquaintances; but in his official character, he should have no intercourse with society but upon public business, or at his levees. Adams, in the conclusion of his reply, ingenuously confessed that his long residence abroad might have impressed him with views of things incompatible with the present temper and feelings of his fellow-citizens; and Jefferson seems to have been heartily of the same opinion, for speaking of Adams in his anas, he observes that " the glare of royalty and nobility, during his mission to England, had made him believe their fascination a necessary ingredient in government." Hamilton, in his reply, while he considered it a primary object for the public good, that the dignity of the presidential office should be supported, advised that care should be taken to avoid so high a tone in the demeanor of the occupant, as to shock the prevalent notions of equality.

The President, he thought, should hold a levee at a fixed time once a week, remain half an hour, converse cursorily on indifferent subjects with such persons as invited his attention, and then retire.

He should accept no invitations, give formal entertainments twice, or at most, four times in the year; if twice, on the anniversaries of the declaration of independence and of his inauguration: if four times, the anniversary of the treaty of alliance with France and that of the definitive treaty with Great Britain to be added.

The President on levee days to give informal invitations to family dinners: not more than six or eight to be asked at a time, and the civility to be confined essentially to members of the legislature, and other official characters — the President never to remain long at table.

The heads of departments should, of course, have access to the President on business. Foreign ministers of some descriptions should also be entitled to it. "In Europe, I am informed," writes Hamilton, "ambassadors only have direct access to the chief magistrate. Something very near what prevails there would, in my opinion, be right. The distinction of rank between diplomatic characters requires attention, and the door of access ought not to be too wide to that class of persons. I have thought that the members of the Senate should also have a right of individual access on matters relative to the 'public administration. In England and France peers of the realm have this right. We have none such in this country, but I believe it will be satisfactory to the people to know that there is some body of men in the State who have a right of continual communication with the President. It will be considered a safeguard against secret combinations to deceive him."

The reason alleged by Hamilton for giving the Senate this privilege, and not the Representatives, was, that in the Constitution " the Senate are coupled with the President in certain executive functions, treaties, and appointments. This makes them in a degree his constitutional counselors, and gives them a peculiar claim to the right of access."

These are the only written replies that we have before ns of Washington's advisers on this subject.

Colonel Humphreys, formerly one of Washington's aides-de-camp, and recently secretary of Jefferson's legation at Paris, was at present an inmate in the Presidential mansion. General Knox was frequently there; to these Jefferson assures us, on Washington's authority, was assigned the task of considering and prescribing the minor forms and ceremonies, the etiquette, in fact, to be observed on public occasions. Some of the forms proposed by them, he adds, were adopted. Others were so highly strained that Washington absolutely rejected them. Knox was no favorite with Jefferson, who had no sympathies with the veteran soldier, and styles him "a man of parade," and Humphreys, he appears to think captivated by the ceremonials of foreign courts. He gives a whimsical account, which he had at a second or third hand, of the first levee. An antechamber and presence room were provided, and, when those who were to pay their court were assembled, the President set out, preceded by Humphreys. After passing through the antechamber, the door of the inner room was thrown open, and Humphreys entered first, calling out with a loud voice, " The President of the United States." The President was so much disconcerted with it that he did not recover in the whole time of the levee, and, when the company was gone, he said to Humphreys, "Well, you have taken me in once, but by — , you shall never take me in a second time."

This anecdote is to be taken with caution, for Jefferson Was disposed to receive any report that placed the forms adopted in a disparaging point of view.

He gives in his Ana a still more whimsical account on the authority of " a Mr. Brown," of the ceremonials at an inauguration ball at which Washington and Mrs. Washington presided in almost regal style. As it has been proved to be entirely incorrect, we have net deemed it worthy an insertion. A splendid ball was in fact given at the Assembly Rooms, and another by the French Minister, the Count de Moustier, at both of which Washington was present and danced; but Mrs. Washington was not at either of them, not being yet arrived, and on neither occasion were any mock regal ceremonials observed. Washington was the last man that would have tolerated anything of the kind. Our next chapter will show the almost casual manner in which the simple formalities of his republican court originated.

Chapter III.

ON the 17th of May, Mrs. Washington, accompanied by her grandchildren, Eleanor Custis and George "Washington Parke Custis, set out from Mount Vernon in her travelling carriage with a small escort of horse, to join her husband at the seat of government, as she had been accustomed to join him at head-quarters, in the intervals of his Revolutionary campaigns.

Throughout the journey she was greeted with public testimonials of respect and affection. As she approached Philadelphia, the President of Pennsylvania and other of the State functionaries, with a number of the principal inhabitants of both sexes, came forth to meet her, and she was attended into the city by a numerous cavalcade, and welcomed with the ringing of bells and firing of cannon.

Similar honors were paid her in her progress through New Jersey. At Elizabethtown she alighted at the residence of Governor Livingston, whither Washington came from New York to meet her. They proceeded thence by water, in the same splendid barge in which the general had been conveyed for his inauguration. It was manned, as on that occasion, by thirteen master pilots, arrayed in white, and had several persons of note on board. There was a salute of thirteen guns as the barge passed the Battery at New York. The landing took place at Peck Slip, not far from the presidential residence, amid the enthusiastic cheers of an immense multitude.

On the following day, "Washington gave a demi-official dinner, of which Mr. Wingate, a senator from New Hampshire, who was present, writes as follows: " The guests consisted of the Vice-President, the foreign ministers, the heads of departments, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, and the Senators from New Hampshire and Georgia, the then most Northern and Southern States. It was the least showy dinner that I ever saw at the President's table, and the company was not large. As there was no chaplain present, the President himself said a very short grace as he was sitting down. After dinner and dessert were finished, one glass of wine was passed around the table, and no toast. The President rose, and all the company retired to the drawing-room, from which the guests departed as every one chose, without ceremony."

On the evening of the following day (Friday, May 29th), Mrs. Washington had a general reception, which was attended by all that was distinguished in official and fashionable society. Henceforward there were similar receptions every Friday evening, from eight to ten o'clock, to which the families of all persons of respectability, native or foreign, had access, without special invitation; and at which the President was always present. These assemblages were as free from ostentation and restraint as the ordinary receptions of polite society; yet the reader will find they were soon subject to invidious misrepresentation; and caviled at as " court-like levees ' and " queenly drawing-rooms."

Beside these public receptions, the presidential family had its private circle of social intimacy; the President, moreover, was always ready to receive visits by appointment on public or private business.

The sanctity and quiet of Sunday were strictly observed by Washington. He attended church in the morning, and passed the afternoon alone in his closet. No visitors were admitted, excepting perhaps an intimate friend in the evening, which was spent by him in the bosom of his family.

The household establishment was conducted on an ample and dignified scale, but without ostentation, and regulated with characteristic system and exactness. Samuel Fraunces, once landlord of the City Tavern in Broad street, where Washington took leave of the officers of the army in 1783, was now steward of the presidential household. He was required to render a weekly statement of receipts and expenditures, and warned to guard against waste and extravagance. " We are happy to inform our readers," says Fenno's " Gazette " of the day, " that the President is determined to pursue that system of regularity and economy in his household which has always marked his public and private life."

In regard to the deportment of "Washington at this juncture, we have been informed by one who had opportunities of seeing him, that he still retained a military air of command which had become habitual to him. At levees and drawing-rooms he sometimes appeared cold and distant, but this was attributed by those who best knew him to the novelty of his position and his innate diffidence, which seemed to increase with the light which his renown shed about him. Though reserved at times, his reserve had nothing repulsive in it, and in social intercourse, where he was no longer under the eye of critical supervision, soon gave way to soldier-like frankness and cordiality. At all times his courtesy was genuine and benignant, and totally free from that stately condescension sometimes mistaken for politeness. Nothing, we are told, could surpass the noble grace with which he presided at a ceremonial dinner; kindly attentive to all his guests, but particularly attentive to put those at their ease and in a favorable light, who appeared to be most diffident.

As to Mrs. Washington, those who really knew her at the time, speak of her as free from pretension or affectation; undazzled by her position, and discharging its duties with the truthful simplicity and real good breeding of one accustomed to preside over a hospitable mansion in the "Ancient Dominion." She had her husband's predilection for private life. In a letter to an intimate she writes: " It is owing to the kindness of our numerous friends in all quarters that my new and unwished for situation is not indeed a burden to me. When I was much younger, I should probably have enjoyed the innocent gayeties of life as much as most persons of my age; but I had long since placed all the prospects of my future worldly happiness in the still enjoyments of the fireside at Mount Vernon.

" I little thought, when the war was finished, that any circumstances could possibly happen, which would call the general into public life again. I had anticipated that from that moment we should be suffered to grow old together in solitude and tranquility. That was the first and dearest wish of my heart."

Much has been said of Washington's equipages, when at New York, and of his having four, and sometimes six horses before his carriage, with servants and outriders in rich livery. Such style, we would premise, was usual at the time both in England and the colonies, and had been occasionally maintained by the Continental dignitaries, and by governors of the several States, prior to the adoption of the new Constitution. It was still prevalent, we are told, among the wealthy planters of the South, and sometimes adopted by " merchant princes " and rich individuals at the North. It does not appear, however, that Washington ever indulged in it through ostentation. When he repaired to the Hall of Congress, at his inauguration, he was drawn by a single pair of horses in a chariot presented for the occasion, on the panels of which were emblazoned the arms of the United States.

Besides this modest equipage there was the ample family carriage which had been brought from Virginia. To this four horses were put when the family drove out into the country, the state of the roads in those days requiring it. For the same reason six horses were put to the same vehicle on journeys, and once on a state occasion. If there was anything he was likely to take a pride in, it was horses; he was passionately fond of that noble animal, and mention is occasionally made of four white horses of great beauty which he owned while in New York. His favorite exercise when the weather permitted it was on horseback, accompanied by one or more of the members of his household, and he was noted always for being admirably mounted, and one of the best horsemen of his day.

[Editor's Note: For some of these particulars concerning Washington we are indebted to the late William A. Duer, president of Columbia College, who in his boyhood was frequently in the President's house, playmate of young Custis, Mrs. Washington's grandson.

Washington's Residences in New York. — The first presidential residence was at the junction of Pearl and Cherry streets, Franklin square. At the end of about a year, the President removed to the house on the west side of Broadway, near Rector street, afterwards known as Bunker's Mansion House. Both of these buildings have disappeared,, in the course of modern "improvements."]

Chapter IV.

AS soon as Washington could command sufficient leisure to inspect papers and documents, he called unofficially upon the heads of departments to furnish him with such reports in writing as would aid him in gaining a distinct idea of the state of public affairs. For this purpose also he had recourse to the public archives, and proceeded to make notes of the foreign official correspondence from the close of the war until his inauguration. He was interrupted in his task by a virulent attack of anthrax, which for several days threatened mortification. The knowledge of his perilous condition spread alarm through the community; he, however, remained unagitated. His medical adviser was Dr. Samuel Bard, of New York, an excellent physician and most estimable man, who attended him with unremitting assiduity. Being alone one day with the doctor, "Washington regarded him steadily, and asked his candid opinion as to the probable result of his case. "Do not flatter me with vain hopes," said he, with placid firmness; " I am not afraid to die, and therefore can bear the worst." The doctor expressed hope, but owned that he had apprehensions. " Whether to-night or twenty years hence, makes no difference," observed Washington. " I know that I am in the hands of a good Providence." His sufferings were intense, and his recovery very slow. For six weeks he was obliged to lie on his right side; but after a time he had his carriage so contrived that he could extend himself at full length in it, and take exercise in the open air.

While rendered morbidly sensitive by bodily pain, he suffered deep annoyance from having one of his earliest nominations, that of Benjamin Fishburn, for the place of naval officer of the port of Savannah, rejected by the Senate.

If there was anything in which Washington was scrupulously conscientious, it was in the exercise of the nominating power; scrutinizing the fitness of candidates; their comparative claims on account of public services and sacrifices, and with regard to the equable distribution of offices among the States; in all which he governed himself solely by considerations for the public good. He was especially scrupulous where his own friends and connections were concerned. "So far as I know my own mind," would he say, "I would not be in the remotest degree influenced in making nominations by motives arising from the ties of family or blood."

He was principally hurt in the present instance by the want of deference on the part of the Senate, in assigning no reason for rejecting his nomination of Mr. Fishburn. He acquiesced, however, in the rejection; and forthwith sent in the name of another candidate; but at the same time administered a temperate and dignified rebuke. " Whatever may have been the reasons which induced your dissent," writes he to the Senate, " I am persuaded that they were such as you deemed sufficient. Permit me to submit to your consideration, whether, on occasions where the propriety of nominations appears questionable to you, it would not be expedient to communicate that circumstance to me, and thereby avail yourselves of the information which led me to make them, and which I would with pleasure lay before you. Probably my reasons for nominating Mr. Fishburn may tend to show that such a mode of proceeding, in such cases, might be useful, I will therefore detail them."

He then proceeds to state, that Colonel Fishburn had served under his own eye with reputation as an officer and a gentleman; had distinguished himself at the storming of Stony Point; had repeatedly been elected to the Assembly of Georgia as a representative from Chatham County, in which Savannah was situated; had bee a elected by the officers of the militia of that county Lieutenant-colonel of the militia of the district; had been member of the Executive Council of the State, and president of the same; had been appointed by the Council to an office which he actually held, in the port of Savannah nearly similar to that for which "Washington had nominated him.

" It appeared therefore to me," adds Washington, "that Mr. Fishburn must have enjoyed the confidence of the militia officers in order to have been elected to a military rank — the confidence of the freemen, to have been elected to the Assembly — the confidence of the Assembly to have been selected for the Council, and the confidence of the Council, to have been appointed collector of the port of Savannah."

We give this letter in some detail, as relating to the only instance in which a nomination by Washington was rejected. The reasons of the Senate for rejecting it do not appear. They seem to have felt his rebuke, for the nomination last made by him was instantly confirmed.

While yet in a state of convalescence, Washington received intelligence of the death of his mother. The event, which took place at Fredericksburg in Virginia, on the 25th of August, was not unexpected; she was eighty-two years of age, and had for some time been sinking under an incurable malady, so that when he last parted with her he had apprehended that it was a final separation. Still he was deeply affected by the intelligence; consoling himself, however, with the reflection that " Heaven had spared her to an age beyond which few attain; had favored her with the full enjoyment of her mental faculties, and as much bodily health as usually falls to the lot of fourscore."

Mrs. Mary Washington is represented as a woman of strong plain sense, strict integrity, and an inflexible spirit of command. We have mentioned the exemplary manner in which she, a lone widow, had trained her little flock in their childhood. The deference for her, then instilled into their minds, continued throughout life, and was manifested by Washington when at the height of his power and reputation. Eminently practical, she had thwarted his military aspirings when he was about to seek honor in the British navy. During his early and disastrous campaigns on the frontier, she would often shake her head and exclaim, " Ah, George had better have staid at home and cultivated his farm." Even his ultimate success and renown had never dazzled, however much they may have gratified her. When others congratulated her, and were enthusiastic in his praise, she listened in silence, and would temperately reply that he had been a good son, and she believed he had done his duty as a man.

Hitherto the new government had not been properly organized, but its several duties had been performed by the officers who had them in charge at the time of Washington's inauguration. It was not until the 10th of September that laws were passed instituting a department of Foreign Affairs (afterwards termed Department of State), a Treasury department, and a department of "War, and fixing their respective salaries. On the following day, Washington nominated General Knox to the Department of War, the duties of which that officer had hitherto discharged.

The post of Secretary of the Treasury was one of far greater importance at the present moment. It was a time of financial exigency. As yet no statistical account of the country had been attempted; its fiscal resources were wholly unknown; its credit was almost annihilated, for it was obliged to borrow money even to pay the interest of its debts.

We have already quoted the language held by Washington in regard to this state of things before he had assumed the direction of affairs. "My endeavors shall be unremittingly exerted, even at the hazard of former fame, or present popularity, to extricate my country from the embarrassments in which it is entangled through want of credit."

Under all these circumstances, and to carry out these views, he needed an able and zealous coadjutor in the Treasury Department; one equally solicitous with himself on the points in question, and more prepared upon them by financial studies and investigations than he could pretend to be. Such a person he considered Alexander Hamilton, whom he nominated as Secretary of the Treasury, and whose qualifications for the office were so well understood by the Senate that his nomination was confirmed on the same day on which it was made.

Within a few days after Hamilton's appointment, the House of Representatives (September 21), acting upon the policy so ardently desired by Washington, passed a resolution, declaring their opinion of the high importance to the honor and prosperity of the United States, that an adequate provision should be made for the support of public credit; and instructing the Secretary of the Treasury to prepare a plan for the purpose, and report it at their next session.

The arrangement of the judicial department was one of Washington's earliest cares. On the 27th of September, he wrote unofficially to Edmund Randolph, of Virginia, informing him that he had nominated him Attorney-general of the United States, and would be highly gratified with his acceptance of that office. Some old recollections of the camp and of the early days of the Revolution, may have been at the bottom of this goodwill, for Randolph had joined the army at Cambridge in 1775, and acted for a time as aide-de-camp to Washington in place of Mifflin. He had since gained experience in legislative business as member of Congress, from 1779 to 1782, governor of Virginia in 1783, and delegate to the convention in 1787. In the discussions of that celebrated body, he had been opposed to a single executive professing to discern in the unity of that power the " fetus of monarchy; ' and preferring an executive consisting of three; whereas, in the opinion of others, this plural executive would be " a hind of Cerberus with three heads." Like Madison, he had disapproved of the equality of suffrage in the Senate, and been, moreover, of opinion, that the President should be ineligible to office after a given number of years.

Dissatisfied with some of the provisions of the Constitution as adopted, he had refused to sign it; but had afterward supported it in the State Convention of Virginia. As we recollect him many years afterward, his appearance and address were dignified and prepossessing; he had an expressive countenance, a beaming eye, and somewhat of the ore rotundo in speaking. Randolph promptly accepted the nomination, but did not take his seat in the cabinet until some months after Knox and Hamilton.

By the judicial system established for the Federal Government, the Supreme Court of the United States was to be composed of a chief justice and five associate judges. There were to be district courts with a judge in each State, and circuit courts held by an associate judge and a district judge. John Jay, of New York, received the appointment of Chief Justice, and in a letter inclosing his commission, Washington expressed the singular pleasure he felt in addressing him " as the head of that department which must be considered as the keystone of our political fabric."

Jay's associate judges were, John Rutledge of South Carolina, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, William dishing of Massachusetts, John Blair of Virginia, and James Iredell of North Carolina. "Washington had originally nominated to one of the judgeships his former military secretary, Robert Harrison, familiarly known as the old Secretary; but he preferred the office of chancellor of Maryland, recently conferred upon him.

On the 29th of September, Congress adjourned to the first Monday in January, after an arduous session, in which many important questions had been discussed, and powers organized and distributed. The actual Congress was inferior in eloquence and shining talent to the first Congress of the Revolution; but it possessed men well fitted for the momentous work before them; sober, solid, upright, and well informed. An admirable harmony had prevailed between the legislature and the executive, and the utmost decorum had reigned over the public deliberations.

Fisher Ames, then a young man, who had acquired a brilliant reputation in Massachusetts by the eloquence with which he had championed the new Constitution in the convention of that important State, and who had recently been elected to Congress, speaks of it in the following terms: " I have never seen an assembly where so little art was used. If they wish to carry a point, it is directly declared and justified. Its merits and defects are plainly stated, not without sophistry and prejudice, but without management There is no intrigue, no caucusing, little of clanning together, little asperity in debate, or personal bitterness out of the House."

Chapter V.

THE cabinet was still incomplete, the department of foreign affairs, or rather of State, as it was now called, was yet to be supplied with a head. John Jay would have received the nomination had he not preferred the bench. Washington next thought of Thomas Jefferson, who had so long filled the post of minister plenipotentiary at the Court of Versailles, but had recently solicited and obtained permission to return, for a few months, to the United States for the purpose of placing his children among their friends in their native country, and of arranging his private affairs, which had suffered from his protracted absence. And here we will Venture a few particulars concerning this eminent statesman, introductory to the important influence he was to exercise on national affairs.

His political principles as a democratic republican, had been avowed at an early date in his draft of the Declaration of Independence, and subsequently in the successful war which he made upon the old cavalier traditions of his native State, its laws of entails and primogeniture, and its church establishment — a war which broke down the hereditary fortunes and hereditary families, and put an end to the hereditary aristocracy of the Ancient Dominion.

Being sent to Paris as minister plenipotentiary a year or two after the peace, he arrived there, as he says " when the American Revolution seemed to have awakened the thinking part of the French nation from the sleep of despotism in which they had been sunk."

Carrying with him his republican principles and zeal, his house became the resort of Lafayette and others of the French officers who had served in the American Revolution. They were mostly, he said, young men little shackled by habits and prejudices, and had come back with new ideas and new impressions which began to be disseminated by the press and in conversation. Politics became the theme of all societies, male and female, and a very extensive and zealous party was formed which acquired the appellation of the Patriot Party, who, sensible of the abuses of the government under which they lived, sighed for occasions of reforming it. "This party," writes Jefferson, " comprehended all the honesty of the kingdom sufficiently at leisure to think, the men of letters, the easy bourgeois, the young nobility, partly from reflection, partly from the mode; for these sentiments became matter of mode, and, as such, united most of the young women to the party."

By this party Jefferson was considered high authority from his republican principles and experience, and his advice was continually sought in the great effort for political reform which was daily growing stronger and stronger. His absence in Europe had prevented his taking part in the debates on the new Constitution, but he had exercised his influence through his correspondence. "I expressed freely," writes he, "in letters to my friends, and most particularly to Mr. Madison and General Washington, my approbations and objections." That those approbations and objections were appears by the following citations, which are important to be kept in mind as» illustrating his after conduct: —

" I approved, from the first moment, of the great mass of what is in the new Constitution, the consolidation of the government, the organization into executive, legislative, and judiciary; the subdivision of the legislature, the happy compromise of the interests between the great and little States, by the different manner of voting in the different Houses, the voting by persons instead of States, the qualified negative on laws given to the executive, which, however, I should have liked better if associated with the judiciary also, as in New York, and the power of taxation: what I disapproved from the first moment, was the want of a Bill of Rights to guard liberty against the legislative as well as against the executive branches of the government; that is to say, to secure freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom from monopolies, freedom from unlawful imprisonment, freedom from a permanent military, and a trial by jury in all cases determinable by the laws of the land."

"What he greatly objected to was the perpetual re-eligibility of the President. " This, I fear," said he, " will make that an office for life, first, and then hereditary. I was much an enemy to monarchies before I came to Europe, and am ten thousand times more so since I have seen what they are. There is scarcely an evil known in these countries which may not be traced to their king as its source, nor a good which is not derived from the small fibers of republicanism existing among them. I can further say, with safety, there is not a crowned head in Europe whose talents or merits would entitle him to be elected a vestryman by the people of any parish in America."

In short, such a horror had he imbibed of kingly rule, that, in a familiar letter to Colonel Humphreys, who had been his secretary of legation, he gives it as the duty of our young republic " to besiege the throne of heaven with eternal prayers to extirpate from creation this class of human lions, tigers, and mammoths, called kings, from whom, let him perish who does not say, 'Good Lord, deliver us! ' "

Jefferson's political fervor occasionally tended to exaltation, but it was genuine. In his excited state he regarded with quick suspicion everything in his own country that appeared to him to have a regal tendency. His sensitiveness had been awakened by the debates in Congress as to the title to be given to the President, whether or not he should be addressed as His Highness; and had been relieved by the decision that he was to have no title but that of office, namely, President of the United States. " I hope," said Jefferson, " the terms of Excellency, Honor, Worship, Esquire, forever disappear from among us from that moment. I wish that of Mr. would follow them."

"With regard to the re-eligibility of the President, his anxiety was quieted for the present, by the elevation of Washington to the presidential chair. " Since the thing [re-eligibility] is established," writes he, "I would wish it not to be altered during the lifetime of our great leader, whose executive talents are superior to those, I believe, of any man in the world, and who, alone, by the authority of his name, and the confidence reposed in his perfect integrity, is fully qualified to put the new government so under way as to secure it against the efforts of opposition. But, having derived from our error all the good there was in it, I hope we shall correct it the moment we can no longer have the same name at the helm."

Jefferson, at the time of which we are speaking, was, as we have shown, deeply immersed in French politics and interested in the success of the " Patriot Party," in its efforts to reform the country. His dispatches to government all proved how strongly he was on the side of the people. " He considered a successful reformation in France as insuring a general reformation throughout Europe, and the resurrection to a new life of their people now ground to dust by the abuses of the governing powers."

Gouverneur Morris, who was at that time in Paris on private business, gives a different view of the state of things produced by the Patriot Party. Morris had arrived in Paris on the 3rd of February, 1789, furnished by Washington with letters of introduction to persons in England, France, and Holland. His brilliant talents, ready conversational powers, easy confidence in society, and striking aristocratical appearance, had given him great currency, especially in the court party and among the ancient nobility, in which direction his tastes most inclined. He had renewed his intimacy with Lafayette whom he found " full of politics," but " too republican for the genius of his country."

In a letter to the French Minister, residing in New York, Morris writes on the 23rd of February, 1789: "Your nation is now in a most important crisis, and the great question — shall we hereafter have a constitution, or shall will continue to be law — employs every mind and agitates every heart in France. Even voluptuousness itself rises from its couch of roses and looks anxiously abroad at the busy scene to which nothing can now be indifferent.

"Your nobles, your clergy, your people, are all in motion for the elections. A spirit which has been dormant for generations starts up and stares about, ignorant of the means of obtaining, but ardently desirous to possess its object — consequently active, energetic, easily led, but also easily, too easily, misled. Such is the instinctive love of freedom which now grows warm in the bosom of your country."

When the king was constrained by the popular voice to convene the States General at Versailles for the purpose of discussing measures of reform, Jefferson was a constant attendant upon the debates of that body. "I was much acquainted with the leading patriots of the Assembly," writes he, " being from a country which had successfully passed through similar reform; they were disposed to my acquaintance and had some confidence in me. I urged most strenuously an immediate compromise to secure what the government was now ready to yield, and trust to future occasions for what might still be wanting."

The "leading patriots" here spoken of, were chiefly the deputies from Brittany, who, with others, formed an association called the Breton Club, to watch the matters debated in Parliament and shape the course of affairs.