4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: hockebooks

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

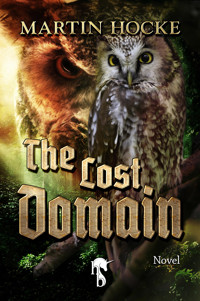

Since time immemorial, the Tawny owls have formed the privileged aristocratic class among the nocturnal birds, far superior to the Barn owls and Little owls. Yoller, the son of the leader of a Tawny owl dynasty, also grew up with this belief. However, when the impetuous young Tawny owl is attacked by buzzards during a messenger mission to remote forest areas, his aristocratic origins do not help him one bit. Yoller is saved from certain death by the owl May Blossom at the last minute. Yoller and his lifesaving heroine fall in love, but conflicting life plans separate them again. Thus Yoller follows his intended purpose as a Tawny owl and returns to his homeland, where he finds himself confronted with the eternal struggle for supremacy in the forests. But the experience with May makes him doubt the old rules ... A relentless system regulates the coexistence of Barn owls, Tawny owls and Little owls. In the land of the owls, violations of these ancient rules are punished with death. But a new era has begun: former enemies inevitably become allies in the fight against a common, old enemy. With poetic wit and captivating powers of observation, Martin Hocke has woven this fantastic trilogy of novels, which revolves around owls and other nocturnal birds, into a parable that stands in the tradition of ‘Watership Down’ and ‘Wind in the Willows’ . Individual volumes: ‘Ancient Solitary Reign’ , ‘The Lost Domain’, ‘Am an Owl’

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 716

Ähnliche

Martin Hocke

The Lost Domain

Novel

For Malcolm Hopsonand with many thanks to Pauline Hockeand Jenny Picton, without whose help, etc.

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

Ecclesiastes, Chapter III, Verse 1

But leave the Wise to wrangle, and with meThe quarrel of the Universe let be:And, in some corner of the Hubbub coucht,Make Game of that which makes as much of Thee.

The Rubdiydt of Omar Khayycim, Verse 45 Done into English by Edward Fitzgerald, 1859

Though much is taken, much abides; and thoughWe are not now that strength which in old daysMoved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in willTo strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, 1809–1892Ulysses

Part One

… a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

Ecclesiastes, Chapter III, Verse 5

Ah Love! could thou and I with Fate conspireTo grasp this sorry Scheme of Things entire,Would not we shatter it to bits — and thenRe-mould it nearer to the Heart’s Desire!

The Rubdiydt of Omar Khayyam, Verse 73Done into English by Edward Fitzgerald, 1859

‘Tis better to have loved and lostThan never to have loved at all.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, 1809–1892In Memoriam

Chapter 1

I am old now and the one most able to tell the story. I shall tell it to the wind and the trees, for none of my own kind will listen.

There are other versions of the truth, of course. But like everything else, the truth is relative. It depends so much on your point of view — on the place where you are standing, or flying at the time. The Barn Owls have produced two epic versions of the historical events I am about to describe. Bardic’s version has now been discredited, even by his own kind. Pompous and flamboyant Bardic, who would tell any version of the facts to gain his own advancement or favour. Quaver’s version stands. His epic ballad holds now as a minor work of art and an accurate chronicle of events, as seen from the white owls’ point of view.

Mine is different. Less lyrical, perhaps, but none the less authentic. I am aware of things he could not have known, and even had he known them, and known them to be true, he would never have allowed these things I shall relate to mar or blur his own pristine vision — his own complex process of rendering history into art.

The Barn Owls are one thing, but we Tawnies are a proud and ancient race, older than most other living creatures, but also a species forced to fight for survival in an ever-changing world. Survival can be a bloody business, and so, as well as love, my story tells of revenge, violence and war. But these are not the aspects of which my fellow Tawnies would altogether disapprove. The reason they would not listen is because I have learned to doubt the ancient wisdom of our days and ways. During my long lifetime I have begun to wonder whether we are really masters of the sky at night, and whether we have the right to drive other creatures from the woodland we have owned and known and where we have thrived for so many thousand springs.

Late in my third age I have begun to ask myself whether instead we might not strive to co-exist with other species, not only here in our ancestral woods, but also in the fields and meadows where the few remaining Barn Owls live, and even in no man’s land with the little upstart owls — yes, even with the squatters, with the unwanted immigrants, call them what you will! But this is, of course, subversive talk, and for even hinting at this philosophy I have long been ostracized and branded a heretic.

The fact is we have always hated upstarts. First we learned to hate the Barn Owls and then — much later — we loathed and despised the little immigrants. We have always considered ourselves superior to all other forms of life, and for this reason none of my class or race would listen to a story which tells not only of our own glory, but also of friendships forged with other species — forged in times of peace and weathered by the storms of war. If these so-called heresies were overheard my life might be at risk. For example, Rowan, son of Birch, might kill me, using my supposed treachery as an excuse to occupy what is left of my ancestral territory. He thinks his own too small and has long awaited the opportunity to be rid of me and thus extend his own domain.

So at twilight and at dawn I shall whisper my story to the trees instead, beginning from the time when I first met and fell in love with May Blossom. Before this fatal moment, there is little of consequence to tell, save that I was well and high born in rich, rolling woodland which my father and his ancestors had owned for centuries. He was leader of the Tawny Owl community in the entire county that stretched further than any owl could fly in a single night, and it was this distance that almost brought about my early downfall and would have done, had not May Blossom saved my life.

My father had sent me with a message to the farthest edge of his estates, and on the outward journey I followed his advice, stopping well before dawn in a large copse where May Blossom and her mother lived. I had some discourse with these two females, but I was tired and it was soon time to sleep. I remember little of what passed between us now, but it may be that in my subconscious the seeds of love were born — born in that brief exchange of courtesies before the rising sun limits our powers of flight and forces us to rest or sleep.

As soon as twilight had deepened into dark, I flew the short distance to the outer limits of my father’s territory, hoping to deliver my message quickly and then return before sunrise to the place where I had slept and rested on the day before. However, as ill luck would have it, the recipient of my message was out hunting when I arrived. I waited patiently at first in the branches of his oak — and then less patiently as the night wore on and dawn approached. On the previous night I had eaten only one large vole and now I dared not hunt for fear of missing Beech on his return.

At last he came. I gave him my message and departed at once, although the night around me was dying and I could already sense the coming light.

Halfway to May Blossom’s copse, I located a young rabbit where the meadow below me bordered on a stream.

By right this rabbit belonged to the Barn Owl incumbent, but being young, headstrong and hungry, I dived, caught the thing and ate it all at one go. It was only the third young rabbit I had ever eaten and this was the plumpest and tastiest of all. A young rabbit is, however, a heavy meal for one Tawny Owl, and afterwards I was so full that I could scarcely fly. I should, of course, have limped my way slowly to the spinney which lay beyond the stream, found a suitable tree and spent the day there to rest, digest my rabbit and to get some much-needed sleep.

Instead I made the near-fatal mistake of flying beyond the spinney and heading on across the fields and meadows towards the large copse where May Blossom and her mother lived. In the meantime the first red streaks of dawn were smearing the night sky, and I knew that soon my powers of flight would begin to fail, slowing me down much more than the succulent rabbit I now carried in my stomach.

No one has ever understood why we Tawnies become inebriated by the daylight, whilst lower forms of owl can fly just as well at dawn or dusk, and some, like the little immigrants, can hunt or travel even by the brightest light of day. This was one of the first things that made me doubt the ultimate supremacy of our species, but for many springs I pushed the question from my mind, supposing that every kind of creature — even Tawnies — must be tarnished by some fatal flaw.

As the sun rose high I found myself within two meadows’ length of my destination for the day. It was then that I saw him coming. Huge, he was, with great widespread wings which seemed to glimmer in the first rays of dawn. Even in the darkness a buzzard is a frightening sight, but their numbers have long been in decline, and since they never fly by night, we hardly ever see them. You might think this strange, since our territories overlap, but since they kill by day and we kill by night, there has historically been very little conflict between our species. The rule however is that if they see a lone Tawny flying in the daylight, they will attack. They will fight to kill, fearing that if we took to hunting in the day, there would be no food left for them. I was brought up to consider this quite fair, since we would do the same if they threatened our woodlands between sunset and the dawn.

The huge eagle-like creature circled in the sky above me, preparing for the attack. I could have tried to make the woodland before he got to me, but tradition has it that we must fight. Never give in, never, never, never. This is part of the Tawny philosophy. Some you win and some you lose, but on your own territory — or territory you have claimed — never surrender, ever!

Wheeling to face the fast-approaching buzzard, I cursed the rising sun and the rabbit in my belly, both of which would slow me down. I must confess I was afraid, even before I saw the second bird approaching, presumably my aggressor’s mate. In our glorious history Tawnies have been known to kill a buzzard in one-to-one conflict, but against two of them I knew I had no chance. Now there was no time to turn and try for help and safety in the woods, so I decided instead to die with honour, a concept that had been instilled into me from birth, but one which I have later come to challenge.

I won the first clash, ripping flesh and feathers from the place where the creature’s wing is attached to its body. Howling with rage and pain, he wheeled and attacked again. Though I struck first myself and inflicted a second wound, he tore what seemed like a huge chunk from my chest. I have often thought how strange it is that in combat one does not feel the pain. Later, yes, but at the time one is merely conscious of the wound. Suffering, or death, come upon one later.

At the third engagement, and even as my strength began to wane, I ripped the creature’s eye out. I did it with my right talons, one of which I was later so tragically to lose. Though not a fatal blow, it put the male buzzard out of action and I knew that it would kill him in the end.

I turned to face the female who had now closed the gap between us and who flew at me with a scream of rage. I damaged her belly in the first encounter, but in the process she slashed my head and ripped a small part of my wing away.

Facing her for the third time, I realised that the end was near. She was strong, furious and yearning for revenge. It was only then that I sensed the fast-approaching presence of another Tawny: a female Tawny flying faster than I could ever do, even without a rabbit in my stomach. As the buzzard and I clashed for the third time, May Blossom rose above my opponent and then fell on her from behind. Striking with both claws simultaneously, with one blow she practically severed the creature’s head. As I fluttered in the sky, with my fast-fading strength, I saw the female buzzard attempt to turn and fight, almost as a reflex — as a chicken will do even after he is technically dead. Then the fatal wound took its full effect, the giant creature fluttered once, spun in the air, and then plummeted to the ground. I turned to locate the male and saw that he had landed in the meadow, not far from the place where his mate was now crashing to her death. For a moment or two I was sorry for her, and especially for him. His, I knew, would be a long and painful death.

‘Come, Yoller!’ May Blossom said. ‘You must fly back to the woods, where you can recover in safety. If you land on the ground, wounded as you are, you will be killed by a kestrel, a sparrow hawk, a stoat or some other daytime creature.’

I nodded, gathered my fast-fading strength for the short flight, and then slowly set off in May Blossom’s wake. It was a short distance, but one I shall never forget.

She had saved my life. She led, I followed. Little did I know then that this was to be the case for so much of my natural life.

Chapter 2

It was during my long period of convalescence with May Blossom and her mother that I first realised the degree of hardship suffered by Tawnies less fortunate than myself. I say degree of hardship, because as you — the wind and the trees — both know, hardship, like wealth, is relative. May Blossom and her mother were not poor. They did not live like the wretched little immigrants, or even like the lowest class of Tawny. Though modest, their territory was not in no man’s land. It was quite a decent-sized copse, just big enough for two. If they were careful and contented themselves with the more plebeian forms of food — like vole or shrew — then there was just enough to eat. For a special treat, say a mole even, not to mention a rabbit, they had to hunt in the Barn Owl country which surrounded them. Being two females, they were loth to create conflict with their neighbours — even though these neighbours were thought to be an inferior species. So special treats were rare.

The other difference between my own background and theirs might be described as aesthetic. It was here with them, as I slowly got well again, that I first learned to appreciate the mighty oaks we had at home. The splendour of the beech trees, the silver colour of the birch, the red berries of the holly glowing bright against the winter snow — all these would have dwarfed and outdone a thousand times in splendour the hazel, dogwood, elder and willows which made up most of the vegetation in May Blossom’s cramped little spinney. There were a few decent maples, some hawthorn with its white blossom, and one wild cherry tree, but there was nothing to compare with the birch, spruce and pine which mixed in such abundance with the native maple, ash and oak in the dense and broad expanse of my father’s ancestral home. But in spite of the cramped circumstances, and the lack of true style or beauty, it was during this period of convalescence that I first fell in love with May Blossom and proposed to her. I fell in love with her because she endowed the small, boxlike home with beauty and intelligence, making the lower trees, sometimes little more than shrubland, seem cosy and welcoming. With her radiance she made the claustrophobic little copse seem as attractive as the splendour and abundance of the mighty woodland to which I would soon return.

Yes, this was when I first proposed to her, and to my sorrow and surprise, she said no.

‘But why not?’ I asked, shocked into a mixture of pain and amazement. ‘My father will give us a part of his territory at least three times the size of this tiny residence. You will live among tall, antique and stately trees and the forest floor below you will be carpeted by bluebells, early purple orchis and wood anemone.’

May Blossom did not reply at once, but looked at me with those clear, bright eyes — eyes which shone with determination and intelligence.

‘You have saved my life, and I love you,’ I continued, hoping that if I insisted she would change her mind. I was strong, young and arrogant at the time and — had heard it said — the most eligible male owl in the entire neighbourhood.

Still looking at me, May Blossom shook her head. ‘We are both too young to mate,’ she said. ‘Before settling down, I want to travel, and most of all, I want to learn.’

I was shocked by this, and the idea of her travelling made me jealous — an emotion I had never experienced before. ‘Where on earth do you want to go?’ I asked. ‘Everyone knows that this is the best place in the world to live. And I am offering you a home in the most beautiful and the richest part of it.’

‘How do you know?’ she asked, still looking at me, but now with her head inclined slightly to one side.

‘How do I know what?’

‘That this is the best place in the world.’

‘Well, of course it is!’ I said.

‘I see, so where else have you lived?’

‘Nowhere else, of course!’

‘Then how can you tell this is the best?’

‘Because everybody says so,’ I replied, beginning to feel rather flustered. ‘Abroad — anywhere beyond these territories — is quite awful, everyone knows that, and Tawnies do not travel well, you must be aware of that yourself.’

‘Hearsay! Hearsay and tradition,’ said May Blossom, with a little smile on what I considered at the time to be the most beautiful face in all of my father’s territories. ‘We don’t know that what our parents and our elders tell us is all true. You may believe it, if you wish, but I need to make certain for myself. And to do that I must travel. Travel far and learn.’

‘Learn what? What is there that you can’t learn here, at home?’

‘I want to know what is happening in the world around us.’

‘What sort of thing?’

‘Well, first of all, I want to know if it is true that man is cutting down more trees. I want to know if it is true that cities, towns and roads are spreading everywhere. I want to know how fast the little immigrants are multiplying and above all I want to know why the Barn Owl population is declining.’

‘Why on earth do you want to know all that? Surely it’s good news for us that the Barn Owls are declining. It’s a bad thing that the Little Owls are spreading, but if the squatters proliferate too much we can either kill them or drive them out, or back to the place whence they once came. As for the woodland, men cutting down more trees is worrying, I admit. But according to our ancestors they’ve been doing it for centuries. That’s how the Barn Owls thrived and prospered in the first place …’

‘I know,’ interrupted May Blossom. She was still smiling, but I detected a hint of impatience in her voice. ‘I know that much history. The Barn Owls prospered because for centuries man has cut down woodland and forest to make the farms and farmland on which the white owls live. But now their numbers are diminishing. Why?’

‘Who cares?’ I said, feeling hurt and rather peeved by the outcome of my proposal. I had hoped for, no, expected a requited love, not history and intellect instead.

‘We have to care!’ said May Blossom, firmly. ‘We have to care, because if man continues to cut down trees to make more farmland, more cities and more roads, we shall no longer have enough traditional territory on which to live. So we, too, shall have to live on farm and meadowland.’

‘You mean have a war with the Barn Owls and then take over their territory?’

‘One day it might be necessary. But what would be the use if our numbers began to diminish, too, like theirs?’

‘Where did you get all this information about man building more roads and cities?’ I asked, now resenting this lovely female for knowing so much more than I did. ‘Who told you about the Barn Owls and the little immigrants?’

May Blossom hesitated before replying. Then she gave me a tight, protective little smile, as if she knew that her answer would provoke a sudden and violent counterattack.

‘A media bird told me,’ she said, lifting her face and keeping the slight smile intact as a kind of challenge.

‘A media bird? You must be mad! How can you believe anything told to you by an owl with no ears — an owl who travels constantly and nests upon the ground?’

‘They are nomads,’ replied May Blossom, facing my onslaught very firmly. ‘They travel. They know what goes on in the world. We don’t. We Tawnies are too insular.’

‘They invent things to get a living!’ I protested. ‘They fly into other owls’ territories and then tell these stories in exchange for the food they steal!’

‘They are not always accurate,’ conceded May Blossom. ‘I admit that in order to stay on and eat well, they may exaggerate from time to time. But I warn you, we ignore them at our peril. The secret is to listen and then to make up your own mind how much is true and how much is invented. But I agree with you, sooner or later one must go and find out for oneself.’

‘Go where?’ I asked, with the uncomfortable feeling that May Blossom had succeeded in turning my own words against me.

‘To a city,’ replied May Blossom. ‘To the biggest city I can find.’

‘You really are mad!’ I cried, now beside myself with despair and frustration. ‘No Tawny Owl in his right mind would live in a village, let alone a town or city.’

‘Some do!’ replied May Blossom, maintaining that infuriating, almost supercilious calm — a semi-patronising air of superiority which was to be of such use to her in later life.

‘Some do, of course they do!’ I countered. ‘But these are Tawnies with no land — outcasts, or criminals long since driven from their ancestral homes.’

‘You believe that because your father told you so,’ said May Blossom, in tones that were quiet but very firm. ‘I happen to know, on the other hand, that some go to the city — and stay there — out of choice!’

‘I don’t believe it! How could anybody bear to live that close to man. I couldn’t survive it for more than a single night!’

‘Ah, but you could!’ May Blossom said. ‘And what’s more, some time you might have to.’

‘Barn Owls can’t!’ I said, triumphantly, at last having found an issue on which I was at least her equal. ‘Barn Owls can’t survive in a town or a city, yet here they live on farmland, much closer to man than we do.’

‘How do you know this?’ May Blossom enquired. The tone of her question was polite, but sceptical, as if my statement was based once more merely on folklore and hearsay.

‘Because a Barn Owl told me so!’ I said.

‘You have spoken to a Barn Owl?’

‘Of course,’ I replied, and then exaggerated by adding: ‘As a matter of fact, quite frequently!’

‘Who is this bird?’ May Blossom asked, challenging my claim with that polite but icy calm which in later years was to be of so much help in furthering her career.

‘Beak Poke,’ I said. ‘He is a very old, decrepit owl whose job is to study the habits of all other birds who fly the skies at night.’

‘He is the Owl Owl on their local council,’ said May Blossom, nodding calmly and then smiling at me in a manner that was almost supercilious in one so lovely and so young.

‘You know him?’ I asked, deflated now that she had yet again taken the advantage from me.

‘Not personally. But I have heard of him, of course!’ ‘Well, he says Barn Owls can’t survive in towns or cities. He says the immigrants can, and we could if we wanted.

But they can’t. Without farmland, pasture and open spaces, they can’t survive.’

‘What do you think of him?’ May Blossom asked, raising her eyebrows slightly.

‘Oh, he’s all right, but as I said before, he’s very old. He doesn’t take care of himself properly. He has no mate and doesn’t seem to bother much about what, if or when he eats. My personal opinion is that he hasn’t long to live.’

‘Frequent him while you can,’ May Blossom said. ‘You can learn much from a bird of his experience and intellect.’

‘He’s an interesting old soul,’ I said, guardedly. ‘But however old and wise, he’s only a Barn Owl after all.’

‘However inferior they may be, Barn Owls are better than we are at certain things,’ May Blossom said. ‘I don’t like to admit it, but it’s true. And if we are to defeat them in the future, we must emulate their strong points, not just despise them for the things they cannot do as well as us.’

‘What strong points?’ I asked.

‘Frequent old Beak Poke, or other clever Barn Owls, and you will find out,’ May Blossom said. ‘Now you are well and must fly home again. I, too, shall leave as this twilight deepens and start my long journey to the city.’

‘Don’t go!’ I pleaded, caring nothing now about Barn Owls, immigrants or man and his threat to our woodland habitat. ‘Come with me instead. Come with me and you can study as much as you want to in my father’s territories. I will not stand in your way. We can mate first and then have chicks later, when you are ready.’

‘My mind is made up,’ May Blossom said. ‘Tonight I fly south, and that is final.’

‘What does your mother think about all this?’ I asked, clutching at some way of preventing her departure. ‘Is she happy to be left here, all alone?’

‘She would be alone if I came with you,’ replied May Blossom, thwarting my emotion with her calm logic — a thing that in the future she was frequently to do.

‘Well, I’d like to talk to her anyway,’ I said, still hoping against hope to enlist the aid of middle-aged Iris to persuade her daughter not to undertake this suicidal mission to the city.

‘Of course you may speak to her, if you wish, but it won’t make any difference,’ May Blossom said. ‘My mind is made up, and I fly tonight, as soon as the setting sun has sunk below the distant crest of your ancestral woods.’

‘Will you wait for me?’ I asked, despairing now that her rare use of poetic language had somehow convinced me, finally, that she was not for turning.

‘It is premature to speak of promises,’ she said, looking at me with eyes that were now softened by a trace of tenderness. ‘I shall not mate, either on the long journey or during my sojourn in the city. My purpose holds to go there, get knowledge and then return to these territories. But I shall be gone for a long time, and during my absence you may be tempted. If this happens — and if you are sure you have found the right owl — obey your instincts and mate with her. But be careful! You are a strong, handsome young bird and when your father dies you will probably become leader of the Tawny Owl community in these territories. Do not take this responsibility too lightly. To do the job well, you will need the right partner, so take care!’

Having said this she smiled and then flew off, without giving me a chance to reply. I sat on the branch of the solitary oak — the only real tree in her humble copse — and waited for her mother to arrive. She did so not long afterwards, while I was still struggling to comprehend and encompass the magnitude of the task May Blossom had imposed upon herself.

‘You look worried,’ Iris said, when she had perched beside me on the branch.

‘I am,’ I answered, and then, after giving her a brief, worried smile, I gazed out far to the west through the sparse trees of the copse, to where the sun was slowly falling in a red ball of fire behind the tall hills of my native woodland. In a few brief moments the red ball of flame would sink into extinction beyond the forest highland, signalling the departure of May Blossom on her long and dangerous quest.

‘It’s no good worrying,’ said Iris, with a little sigh. ‘May Blossom is headstrong, always has been. She’s had her own way ever since she was a fledgling. Ever since her father died.’

‘But it’s so dangerous,’ I said. ‘And the city is so far away. I’ve asked her to mate with me. Is there nothing you can do to make her change her mind?’

‘I have already tried,’ said Iris, sadly. ‘But once May Blossom has made up her mind, there’s nothing any one of us can do. She’s determined to travel and get knowledge. I can only hope and pray to the God Bird that I live to see the sunrise of her safe return.’

I nodded absently as I watched the sun sink still further behind the distant hills. ‘Well, I will try to wait for her,’ I said. ‘But it won’t be easy. With the coming of each spring, it won’t be easy not to mate.’

‘May Blossom has told me that you must not hesitate,’ her mother said, looking at me with worn but kindly eyes. ‘For my part, I have told her she is missing the best and biggest life-chance she may ever get. What more can I say, or do?’

‘Nothing!’ I replied, watching the last of the flaming ball drop into oblivion beyond the distant hills. Now it was moonlight, now reigned the night. ‘Tonight I shall fly home,’ I said. ‘But I shall never forget your kindness, your care and your hospitality. Most of all I shall never forget that May Blossom risked her life for mine. If you need help, call and I will come.’

Iris gave me another sad, brave smile and nodded, close to tears, as I took off and flew west and homewards. Owls, even Tawny Owls, have hearts, in spite of all the bold exterior, the casual talk and the natural phlegm. Mine was breaking as I flew. It was torn and rent asunder as at least a half of it flew south, following the beautiful and intrepid May Blossom on her relentless quest for knowledge. Flying across Barn Owl country towards my own distant hills, I wept, for the first time since my first days as a fledgling. I wept for a love that I somehow sensed, whatever happened, would never be the same again.

As dawn rose I reached the last stage of my homeward journey and rose higher in the red-streaked sky to complete the flight back into the woodland of my ancestral domain.

Above a spinney in the foothills — before the real woodland began — I came across an early-morning sparrow hawk poaching in our night-time territory just a few moments before dawn. Though these little hawks are fierce opponents, and though I was still not well enough to fight, I dropped on the thing as it scavenged low above the ground.

The vicious little killer turned on me as I swiftly homed in and hit it from the still-dark sky. Before I tore its throat out with my strong talons, it clawed me in the chest and opened up the wound I had been nursing since my battle with the buzzards. I gasped in pain as the dying creature fluttered its short distance to death upon the ground. Feeling the warm blood trickle down from my chest to my nether belly, I flew slowly on to the heart of my homeland across the thickening forest that I loved so well.

As I completed the last stage of my journey, I was sorry for the dying sparrow hawk I had left behind. Now, with the tolerance and weakness that have come upon me with the passing years — now I would have flown on high above the poacher and left it to scavenge in the spinney and the woodland foothills throughout the coming day. But at that time I was young and bold, teeming with frustration and above all carrying that deadly mixture of a wounded ego and a broken heart. Often, in later life, I have wondered how a young male’s ego could be tamed or in some way channelled into compassion to avoid so much of the senseless suffering and bloodshed that seem to repeat themselves in every generation. But that night — apart from a passing regret for the sparrow hawk who had died because he began hunting early, only a few moments before dawn — my heart and mind were occupied by May Blossom’s departure and my own bloodstained return home.

Selfish, and occupied with our own small concerns, we do not see the changes in the wider world around us until it is too late. But it was ever thus, and now, approaching my third age, I still see little chance of any change.

Chapter 3

Bleeding, and snatched from death by May Blossom, I returned like the prodigal son and was thus welcomed by my parents, who were overjoyed to see me.

I had not realised how much they cared. I had always taken it for granted that they loved me and I, of course, loved them, bestowing the correct degree of filial affection and respect.

As I have already mentioned, any outward expression of emotion is considered bad form by any true, self-respecting Tawny. But for a while, in their delight at seeing me and in their grave concern about my wound, some of these false barriers fell, and so — in this new mood of intimacy — I told my parents about May Blossom.

To my great relief — and considerable surprise — my father was not half as disapproving as I had imagined. ‘I think I remember her vaguely,’ he said. ‘She seemed a clever, handsome, bright-eyed bird. Of course, I recall her mother Iris very well, and her father, poor old Forest, who was murdered by a buzzard. By two buzzards, as a matter of fact.’

‘Could it have been the same two?’ I asked, for of course my parents and the whole district already knew about the battle May Blossom and I had won above the meadowland such a short distance from the daytime safety of the nearby spinney.

‘Probably,’ my father said. ‘Forest was killed only two springs ago. Anyway, the district is well rid of them, and I am very proud of you, my son. Also, you should not allow the killing of the sparrow hawk to prey upon your conscience. We are well rid of him, as well, and it will serve as a warning to other daytime raptors. The territory is theirs by day and ours by night. It was ever thus. Lore and tradition must be respected, in the natural way. They kill by day, we kill by night. They must not be allowed to encroach upon our rights.’

‘But it was only a few seconds before dawn,’ I said. ‘I could have pretended not to notice him and flown on by.’

‘You did your duty,’ my mother said, anxiously staring at my chest to check that the blood was now oozing more slowly from the re-opened wound.

‘On the subject of land rights and encroachment,’ my father added, ‘rumour has it that a squatter has taken up residence on Beak Poke’s land. This is too close for comfort. Once you let these wretches in, you will never be rid of them.’

‘A Little Owl?’ I asked.

‘Vermin!’ my father said. ‘This one is said to be a female, and she has been reported as poaching in the copse where you killed the sparrow hawk at sunrise.’

‘But the copse is strictly classified as no man’s land,’ I said. ‘That’s why the sparrow hawk is on my conscience. These creatures must feed somewhere, and I understand that these immigrants can also hunt by day, not only at night, as we do. So where lies the threat to us?’

‘The thin end of the wedge!’ my mother said, the harsh tone in her voice contrasting strangely with the tender concern in her eyes as she continued to observe the fast-abating drips of blood from my chest. ‘If we let these poachers in, they will multiply. If this immigrant Beak Poke harbours is a female, she will breed. And breed fast, like a sparrow or a rabbit. Soon the copse will be swarming with them. They won’t have enough to eat, so as sure as tomorrow’s dawn, they’ll spread into our woodland territory by day, taking vole, mole and shrew from the forest floor and contaminating the place with their multiplying presence. Soon no self-respecting Tawny will want to live with such daytime neighbours. The woodland we have inhabited for many thousand years will be devalued.’

‘She’s right!’ my father said.

‘So what do you want me to do?’ I asked, my heart still flying with May Blossom, but at the same time sinking at the thought of more carnage. ‘Do you want me to fly back there tonight and kill the wretched thing?’

‘No!’ my father said emphatically. ‘You are hurt and must first recover from your wound. In any case, if I wanted a mere execution, I would send a lesser owl, like Birch. Though young, he is already good at that kind of thing. All you need to do is to speak to the decrepit Beak Poke. Tell him to expel the little immigrant from his land. That way she will no longer have access to the copse, or to the lower regions of our territory.’

‘I will try,’ I said, nodding as the pain in my chest began to ebb now, rather than flow fiercely as it had done on the last stretch home after my encounter with the sparrow hawk. ‘But you know how Beak Poke is, and you know the brief he has been given?’ I added, determined to capitalise on what little knowledge I had of the old white bird who lived on the flat Barn Owl territory, beyond the edge of our woodland domain. ‘You know that he is Owl Owl on their local council. You know that his job is to study and to monitor the behaviour of all other birds who fly by night?’

‘Of course I know!’ my father said. ‘We have been monitoring his behaviour since he first came here twelve or thirteen springs ago. At first we thought he might be a spy, but for a long time now we have been satisfied that he is genuine — merely a scientist obsessed by his own research. From time to time he has younger Barn Owls living with him to study what they call owlology. Of course, he is a bad influence on the district, but not a direct threat to our security.’

‘What do you mean by a bad influence?’ I asked, wondering how such an astute but dilapidated old bird as Beak Poke could ever have been seen as any kind of menace.

‘Because he encourages squatters,’ my father said. ‘I want you to tell him that we disapprove of this, and if he persists in harbouring little immigrants, I may have him killed.’

‘I’ll try to explain it to him,’ I said. ‘But to tell you the truth, I don’t think he will listen. By now I imagine he’s too old to care whether he gets killed or whether he is merely permitted to work on until the time soon comes for him to die a natural death.’

‘Be that as it may,’ my father said, in the rather old-fashioned way he had of speaking, ‘the fact remains that if you don’t go and do it peacefully, I’ll send Birch instead.’

‘And if Beak Poke doesn’t accept your conditions, Birch will kill him?’

‘We are not barbarians here,’ my father said. ‘But if that desiccated old Barn Owl harbours immigrants on land adjacent to our own, then kill him we must. To preserve our heritage. This is why I am asking you to mediate. Because you know him. If your attempt fails, we shall send in Birch, who does not suffer from your scruples and will eliminate them both.’

‘Both Beak Poke and the little squatter?’

‘If this white bird refuses to co-operate, there will be no alternative,’ my mother said. She spoke these words without compassion, but rather with an undisguised contempt. Because I knew she loved me, I could not understand why she was unable to extend that love, or at least charity, to other creatures of the night. It struck me that the ancient Beak Poke and the Little Owl who squatted on his land must both at some time have had mothers. Would these same mothers have been as pitiless as mine?

I did not understand it then, I do not understand it now, and it is partly due to this lack of comprehension that those of my own kind have now branded me as a heretic and threatened me with death. Would my mother have approved of this, I wonder?

She would not have approved of my so-called heresies, of this I am certain. But would she have condoned the eviction of her only and now ageing son from the ancestral domain where he was born and which she once loved so much?

Eviction or death, these are the alternatives that face me now, as I tell my story to the wind and the trees. Now I must make the same choice as my parents then imposed on Beak Poke and his little squatter. How would my mother have reacted, if she could have seen the roles reversed? It is too late to know, for she is now long dead.

Anyway, two nights later, when my wound had ceased to bleed, unwillingly I went. I flew down from the heart of our thickly wooded homeland to the copse that bordered on the meagre fields and meadows which comprised Beak Poke’s territory — a territory I suspect which most other Barn Owls of his status would have considered as something less than a desirable domain.

Having reached the copse, I flew into my favourite willow, perched in one of the upper branches, and looked down through the darkness at the sluggish waters of the lowland stream, comparing the brackish, almost stagnant trickle with the wild water which burst from the rock source where I was born and where I am perching now. Here the stream gushes from the rocks and surges down the hill, slowly faltering in the foothills as it loses its native force and slows down to meander and dribble across the uninspiring plain.

Yes, as I perch here now, high in my native woods, toward the pain-racked end of my long days, I see the same stream gushing from its hillside source and remember well how I tried to brief myself that long-vanished night for confrontation with the white, wise old bird who lived, moved and had his being on the insipid patch of flatland below the willow and beyond the stream. Recalling my previous, casual encounters with Beak Poke, I came then to the conclusion that he really lived inside his head. He was an owl who lived inside his own mind and therefore the beauty or external status of his domain were of no consequence to him. As I perched high up in the willow, plucking up courage to confront him, it struck me that he could exist as well in no man’s land. Only what went on inside his mind and inside others’ heads was of concern to him.

This is why I perched in the willow for a while and peered down at the brackish stream below me in search of inspiration. Physically, of course, I was not afraid of him. I could have killed old Beak Poke with one single blow. But I was afraid of his mind — of his ancient but not yet addled brain. Yet at the same time I realised that my parents were quite right. Owls who lived here on the plain, in close proximity to humans, must perforce be inferior to us. And if they began to harbour little immigrants on their dull, lowland territory, where would the conflict ever end?

But I digress! My thoughts were not only with Beak Poke and the coming confrontation, but also with the female that I loved. How could I have doubts about the simple mission with which I had been entrusted when she had flown to the monstrous, far-off city to get knowledge?

With May Blossom in mind, I took off from my perch in the willow, flew across the stream, out of the copse and into the open country in search of the old white owl, determined to tell him that unless he got rid of his little squatter he would be condemned to death.

But — as it happens in bad dreams — I saw the little squatter first. Flying across flat Barn Owl country in the direction of the abandoned farmhouse where Beak Poke lived, I saw her flit across the hedge between the meadow and the man-made road below me. Wheeling above I watched as she flew into the shelter of a hollow tree. For some moments I hovered in the midnight air, wondering what my father would have done. Perhaps he would have dropped down from the dark sky and killed the creature without warning.

Urged on to kill by duty to my class and to my ancient race — to my kith, kind and stock — and yet held back by understandable reluctance to bloody my talons on yet another form of life, I veered in the sky and headed across the flat, neglected meadow towards the dilapidated building in which the ancient Barn Owl spent the last nights of his lifetime on research into comparative owl history and behaviour.

On powerful young wings, I crossed the meadow quickly and hooted to announce my coming. There was no answer from within so I dropped down from the sky, landed on the roof and hooted once again, but yet again no answer came.

As I knew then, Barn Owls cannot hoot properly, as we do, but merely screech or hiss in the most unmelodious way, though I have since learned that they themselves find this ghastly sound quite harmonious and attractive.

I perched for a while on the roof, hooted once more and, when no reply came, concluded that Beak Poke was out hunting somewhere above the dull field and meadowland in which he lived. I took off from the roof and flew back towards the copse on the edge of the forest, intending to wait in the willow above the stream until the old bird should make his presence in some way manifest. But crossing the narrow asphalt road, close to the gate and the hollow tree, I saw him homing in from the west far below the midnight crescent of the moon. He must have heard my powerful hoot and responded by flying towards me on his worn and desiccated wings, too ashamed — as I thought then — to call out to me with that awful Barn Owl screech or hiss.

Higher than he in the night sky, I hovered above the five-barred gate beside the road and watched him come, flapping towards me in the dotage of his old and crippled flight. As I dropped down from the sky to meet him a flood of white light lit up the road below.

This blinding flash emanated from one of the metal creatures man has made, bred or taken into captivity to transport him at high speed, not only in the ghastly city to which May Blossom had gone in search of knowledge, but also here in the depths of the countryside, where their noise, fumes and appalling smells molest our ancient and sacred reign.

High in the sky I watched as the aged Beak Poke flew across the road in front of the speeding vehicle and the blinding light. Low down, on his weak and desiccated wings, he paused halfway across the narrow strip of tarmac, dazzled by the bright white light projected by the eyes of the metal creature that tore towards him.

It was all over in seconds, and there was nothing I could do. The man-made or man-bred vehicle hit him at full speed, as he hovered there only two or three owl-lengths above the road.

Though high up in the sky, I too was partly dazzled by the blaze of bright white light, and only when the destructive thing had passed and vanished into the night was I able to discern Beak Poke’s broken body lying in the middle of the narrow strip of road. Deeply shocked, I began to fly downward, though even at that safe distance I gathered that he must be on the verge of death, for he was muttering some gibberish that sounded like a prayer.

Before I had time to descend to within swooping distance of the road, a shadow flitted from the hollow tree below me as the little immigrant emerged from her squatter’s hiding place and flew to the middle of the asphalt track to perch beside Beak Poke’s shattered body.

Not knowing what to do, I hovered as she spread out one of her ragged, rounded little wings and held it over Beak Poke’s broken head and neck as if trying to provide some comfort, or perhaps in an attempt to use some alien magic to bring him back from death.

The little alien must have sensed my presence — known that I was there — hovering high above her in the sky. In spite of this her purpose of compassion held and I sensed that she did not flinch at the prospect of a sudden death, a death similar to the one which both of us had just witnessed.

For a time I watched and hovered, wondering whether to swoop down and kill the little creature. If I did, my parents would be pleased with me, I knew, but after long hesitation I realised that I could not bring myself to do it. I could not bring myself to kill a creature — alien or not — when she was attempting to comfort in extremis one who had just been struck by sudden death.

So I turned in the sky, flew back to the willow in the copse and perched on my favourite branch, high above the slow meandering of the brackish stream. Here I stayed for quite some time, wondering as the night wore on what I must say to my parents about the mission I had been unable to complete.

Little did I realise then that my failure to execute the little alien was to have a profound effect, not only on my own life and on the lives of my fellow Tawnies, but also on the future of the Barn Owls and on the destiny of the ever-growing immigrant community. Most of all my reluctance to kill was to affect the future of the life-long friend I was destined to meet for the first time in this same copse and this same willow tree on the following night.

Though young, strong and arrogant, I was loth to kill. Had I done so then, as my parents would have wished, the recent history of we creatures who fly the sky at night might have taken an entirely different course. I am not saying whether it would have been for the better or for the worse. But different, yes! Different it would have been. But it is too late now to speculate, and in what way different, now only the wind and the trees will ever know.

Chapter 4

Flying home just before the first pale light of dawn, I caught a kestrel poaching on the lower reaches of our land. Reluctantly, I killed it, but kestrels are vicious little creatures and this one ripped my healing chest in his bold but vain attempt at self-defence. Since I had not dined that night, I ate the thing, though again, with great reluctance. It was the first and last time I ever ate another bird of prey, though we Tawnies are brought up to believe that consuming another raptor will give us greater strength and courage. I suppose I did it then to prove something to myself and to my parents.

Certainly arriving home with fresh blood oozing from my chest — and with the news that I had sustained this wound in the course of killing and then devouring a daytime raptor — provided an extenuating circumstance for not having properly fulfilled my mission.

‘You should have killed the squatter!’ my mother said, when I finally arrived home.

‘But I was brought up to respect the dead. Brought up by you!’ I said.

‘You were brought up to respect our dead. Not the death of an ancient, decrepit Barn Owl, much less the life of an alien — an unwanted immigrant, whose species threaten our ancient solitary reign.’

‘Father, what do you think?’ I asked, determined to discover whether my sparing of the alien had been born of cowardice, of compassion — or of both.

‘You must go again!’ my father said. ‘You must return the night after tomorrow and kill the thing. Otherwise I shall send Birch to do it. As I’ve told you before, he likes that kind of thing.’

‘But wouldn’t it be better to wait a night or two and see if Beak Poke’s pupil appears,’ I said, clutching desperately at straws.

‘What pupil?’ my father asked.

‘A new one. The last time I spoke to Beak Poke he told me he was expecting this student who had been allocated to him for the study of owlology.’

‘I thought he was too old for that kind of thing,’ my father said. ‘I thought he had retired from teaching.’

‘Apparently he did, for a while, but as the result of a special request, he was persuaded to take it up again.’

‘Well, he can’t, because he’s dead,’ my mother said in that flat, pragmatic drawl that showed her class and breeding. ‘Beak Poke is dead and so this young Barn Owl will have to go somewhere else to study, leaving the land to become infested by the friends and relations of that little squatter.’

‘Quite right!’ my father said. ‘All the more reason to kill the creature now.’

‘But it is still Barn Owl territory!’ I protested. ‘Are we allowed to kill things on their land, without first asking for permission?’

‘A Tawny Owl can kill anything he likes,’ my mother said. ‘And asking other creatures for permission is not the way to get things done.’

‘But Yoller has a point,’ my father surprisingly conceded. ‘According to the treaty we made with them after the last war between us — four hundred winters since — we have to inform them before killing any creature that lives, moves or has its being on their land. And under the same reciprocal agreement, they are not allowed to touch even a mouse or a shrew on ours.’

My mother gave my father a glacial stare — that glacial, disapproving stare which had terrified me since I was a fledgling. It was such a cold look that I had always thought it would freeze most living creatures even at the distance of a meadow.

‘Very well, then,’ my mother said eventually. ‘Give this young bird a chance. Go there tomorrow night and see if he has arrived and, if so, whether he intends to stay or not. If he decides to stay, tell him to get rid of the little immigrant. If he decides to go elsewhere, you must kill the thing yourself.’

I thought about this very quickly and decided to accept. At least it gave me some breathing space. And if the young Barn Owl didn’t put in an appearance, or else decided to leave straight away, when the time came to kill the little immigrant I could still refuse and let Birch do it. As my father had pointed out, Birch loved that kind of thing, as does his son Rowan, who is waiting to kill me now.

So two nights later I flew back to Beak Poke’s territory in search of the new incumbent. I found him sooner than I expected. He was quartering the floor of the copse, close to the slow-running stream. Descending from above I must have taken him by surprise, for he turned upward and hissed at me as though he thought I was about to attack him. He was a big, strong young bird, and courageous, I could tell. If attacked, he was obviously ready to sell his life as dearly as he could.

In order to set his mind at rest, I hooted as melodiously as I was able.

‘To tell the truth you gave me quite a shock,’ he said, as we met and hovered opposite each other at eye level.

‘Your shadow felt so big that for a moment or two I thought you were the monster owl come back to claim his own.’

‘Good heavens, no!’ I said. ‘The monster owl is at least three times as big as I am, and if I’d been him you’d have been dead and torn to pieces at least ten times over before you realised what was happening. In any case, it’s at least nine hundred winters since a monster owl was seen in any of these territories. The general theory is that they are quite extinct.’

‘Not according to our information,’ the young Barn Owl said. ‘Apparently many of them are still living, but in other countries, far across the salty waters. Though we know that one was seen only two thousand meadows north of here less than fifty springs ago.’

Something about the way the young Barn Owl said this struck me as arrogant and annoying. My father hid always told me that our Tawny Owl intelligence network was superior to those used by any other form of living creature.

‘If you ask me, that’s all an old crow’s tale,’ I said. ‘Probably just a story that your parents tell you to frighten you and get you to behave. You know the sort of thing — Behave yourself, little chap, or the monster owl will gouge your eyes out — and all that sort of rubbish.’

‘Shall we perch somewhere for a moment?’ the young Barn Owl asked, and from the respectful tone of voice he used I could tell that he’d got my message.

‘Right ho, then,’ I said, relenting a little. ‘I don’t mind if I do, though I can’t stay long because I haven’t had my dinner yet. I just thought I’d pop over this way and see whether you’d arrived and how you were settling in.’

‘You knew I was coming?’ he asked, as I led him to the willow and we settled side by side on my favourite branch above the slow-running stream.

‘Of course I knew. By the way, my name is Yoller. What’s yours?’

‘Hunter. But how did you know that I was coming?’

‘Old Beak Poke told me just the other night. Incidentally, I hope you’re finding enough food to eat. I’m afraid the poor old boy got rather feeble towards the end. He let the place run down pretty badly, sad to say.’

‘Towards the end?’

‘Yes, towards the end the poor old fellow was almost geriatric, I’m afraid. Poor old bird, I bet he didn’t know what hit him.’

‘What did hit him?’ Hunter asked.

‘Oh, you know, one of those things men tear about in on the roads. I suppose the poor old chap was dazzled and just flapped straight into it instead of veering to one side. I must say I’m surprised you hadn’t heard.’

‘I didn’t even know that he was dead,’ said Hunter, who looked and sounded very shocked. ‘When exactly did it happen?’

‘Two nights ago.’

‘Did you see it happen?’

‘I didn’t see the actual impact. The thing with lights on had just begun to move again when I arrived and saw old Beak Poke lying in the road. I flew down to him at once, but there was nothing I could do.’

Of course, I was lying, but I thought then for a good purpose. I did not tell Hunter that the female immigrant attempted to comfort the ancient Beak Poke as he lay dying because I did not want him to feel any sympathy for the unwanted little creature. This tampering with the truth I thought at the time was the lesser of two evils. If Hunter evicted the immigrant I would not have to kill it, or worse, I wouldn’t have to abdicate, lose face and leave the task to the bloodthirsty Birch.

‘Did he say anything before he died?’ asked Hunter.

‘Not much, actually,’ I answered. ‘At any rate it wasn’t very clear. He was babbling something incoherent — some sort of gibberish that might have been a hymn or prayer.

I suppose the pain and shock had addled his poor old brain and on the point of death he had no idea of what he was saying.’