6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

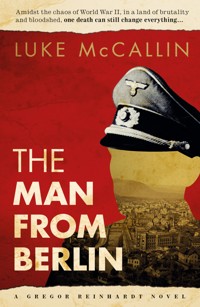

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A Gregor Reinhardt Novel Shortlisted for the 2015 CWA Endeavour Historical Dagger In war-torn Yugoslavia, a beautiful young filmmaker and photographer - a veritable hero to her people - and a German officer have been brutally murdered. Military intelligence officer Captain Gregor Reinhardt, already haunted by his wartime actions, is assigned to the case. He soon finds that his investigation may be more than just a murder - and that the late Yugoslavian heroine may have been much more brilliant - and treacherous - than anyone knew. Reinhardt knows that someone is leaving a trail of dead bodies to cover their tracks. But those bloody tracks may lead Reinhardt to a secret hidden within the ranks of the powerful that they will do anything to keep. And his search for the truth may kill him before he ever finds it. 'I'm reminded of Martin Cruz Smith in the way I was transported to a completely different time and culture and then fully immersed in it. An amazing first novel.' Alex Grecian, author of The Yard 'An extraordinarily nuanced and compelling narrative' Kenneth Allard, New York Journal of Books 'A wild ride...with plenty of twists and turns. This debut novel will make you salivate for a sequel.' Charles Salzberg, author of the Shamus Award-Nominated Swann's Last Song and Swann Dives In

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

LUKE McCALLIN

Luke McCallin was born in Oxford, grew up in Africa, went to school around the world and has worked with the UN as a humanitarian relief worker and peacekeeper. His experiences have driven his writing, in which he explores what happens to normal people put under abnormal pressures. He lives with his wife and two children in an old farmhouse in France. He has a MA in political science, speaks French, Spanish, and a little Russian. His next bookThe Pale Housewill be published by No Exit Press next year.

Contents

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Part Two

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Part Three

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Part Four

44

Cast of Characters

Copyright

Part One

The City

1

SARAJEVO, EARLY MAY 1943

MONDAY

Reinhardt shuddered awake, again, clawing himself up from that dream, that nightmare of a winter field, the indolent drift of smoke and mist along the hummocked ground, the staccato line of the condemned and the children’s screams. He rolled his feet to the floor, sitting slumped on the side of the bed with his head in his hands, and listened to the calls to prayer sounding in ones and twos from the minarets as the sun rose across the Miljačka valley. Eyes glazed with fatigue, an ache in his head and an acid churn in his belly, he watched without seeing the crawl of light across his room, his mind still floundering to escape the clutches of his dream. He jerked as he smelled smoke, an acrid sting of memory, and blinked it back. Only a memory, but another sign of the inside leaking out more and more into his waking world. He wondered if he was going mad.

With trembling hands he lit a cigarette. His head swivelled to the side as he drew deeply, then tilted back as he exhaled through puffed cheeks, his eyes closed, the hangover beginning to bite. The smoke swelled up above him, rising, dissipating. Reinhardt watched it for a moment then let his head sag over his fingers, curled like a cage around the cigarette. Gingerly, he ran a fingertip across his temple, feeling the dull bruise beneath the skin where, more and more, the weight of his pistol was the last thing he felt at night.

Someone knocked at the door, and he froze, startled out of the fog of his thoughts. The knocking came again, and his name, muffled through the door. He put a hand on the bedside table and pushed himself quietly to his feet, but his arm felt numb and heavy from where he had slept on it, and it slipped, slid, and bumped the pistol, which clattered and clinked against the bottles and glasses.

Reinhardt stared guiltily across the room in the sudden silence. The knocking came again, louder. He put out his cigarette, gritting the stub into a whisper of ash; put a hand out to the wall to steady himself as his left knee gave its usual twitch; and began to shuffle down the side of the bed. He rested both hands on either side of the door frame, breathed deeply, and rolled his head on his neck, feeling the ache skitter around inside his skull like a steel ball in a bowl, and ran a finger across the bruise at his temple. Another deep breath, and he threw the latch back on the door and flung it open.

A soldier stood in the hallway outside, a fist raised to hammer the door again. Steely eyes regarded him from under the rim of a field cap, a sergeant’s insignia on his broad shoulders. For a moment there was silence, and Reinhardt realised he must make quite a sight, his hair tangled, shirt twisted out of his trousers, and his feet in socks.

‘Captain Reinhardt?’

Reinhardt looked at him through the spreading ache behind his eyes, half recognising him. ‘I think you bloody well know who I am.’

The man put his heels together and saluted. ‘Sergeant Claussen, sir. I have orders for you to report to Major Freilinger immediately.’ The man was built like a boulder, short and squat with his uniform stretched taut over his chest and belly.

Reinhardt stared at the sergeant. ‘To Major Freilinger?’ he croaked. He coughed, swallowed, and tried again. ‘Freilinger? What does he want?’

‘There has been a murder, sir,’ said Claussen.

‘Murder?’ Reinhardt put his hand behind his neck and rubbed it, turning his head from side to side. He thought he saw Claussen’s eyes stray to the mark he was sure was on his temple, and he straightened up. ‘What’s that got to do with us? This city still has a police force, doesn’t it?’

‘Major Freilinger instructed me to tell you that one of the victims is a fellow military intelligence Abwehr officer. Lieutenant Hendel.’

‘Stefan Hendel? Freilinger said he was Abwehr?’ Claussen nodded. ‘Very well. Give me ten minutes.’

‘Yes, sir. Ten minutes.’ Claussen was an experienced NCO. The four green stripes of a master sergeant on his arm were proof of that, and a good NCO knew how to frame a statement to an officer so it sounded like an order. Reinhardt flushed again at the picture he must make, picked up his towel and toiletry bag, and stalked out of his room down the corridor to the bathroom.

He bent over one of the sinks as he felt the churning in his stomach come heaving up. He retched, his head beginning to pound as he doubled over but, as so often, nothing came up, only a sickly rasp of bile, like the viscous residue of his life and work. His stomach calmed, eventually, and he shivered as he stayed bent over the sink, the hammering in his head turning into a dull ache that squatted in the top of his skull.

He rested his head in his hands, eyes pressed into the heels of his palms. Another night and he had hardly slept, and what sleep he managed gave him no rest. Another night spent in the cells under the prison, facing prisoners of war across bare rooms under caustic lights. Another night spent piecing together the puzzles these men represented, pulling together information and intelligence from a dozen other interrogations from the nights and days before them, here and elsewhere. Norwegians, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Australians, Arabs… now Yugoslavs. Partisans. They had all come and gone in front of him since this war started.

The pipes shuddered and coughed a spray of water into the cracked porcelain of the basin. He swallowed a couple of aspirin, drank as much water as he could, then carefully shaved, looking through his reflection. He rinsed off and only then allowed himself to look in the mirror. Not quite as bad as he felt, he saw. Dark blue eyes like pits, cheeks gaunt above the tight line of his mouth, the close-cut cap of his brown hair greying at his temples. An average face. One that would go unnoticed in a group of three men, as his old police instructor used to joke.

He wet his tousled hair, combed it, splashed cologne on his face and water in his armpits, and he was done. He looked in the mirror a last time, wiping away the steam to stare at himself.

‘As good as it gets,’ he muttered, pulling out the light and walking back to his room. Reinhardt shut the door in Claussen’s face, let his trousers puddle around his feet, then peeled off his shirt and let his underpants and socks join the heap on the floor. Outside, the call of the muezzins faded away across the valley that held the town of Sarajevo cradled in its slopes. As if needing to fill the silence, the bells of St. Anthony’s, up behind the barracks, began to toll.

Outside came the squeal of the trams at Vijećnica as they went around the corner at the city hall. He twisted his shoulders into his braces, sat to pull on his boots, pausing a moment to stare at the picture of his dead wife in its silver frame on the bedside table, tracing a fall of hair with a fingernail along the glass.

Reinhardt placed the picture gently into a drawer and wound his watch. It was just a cheap Phenix, but winding it always made him think of the watch he had left behind in Berlin with Meissner, for safekeeping. A pocket watch, heavy, old fashioned, a British-made Williamson hunter with an inscription on its silver casing, and the memory of his finding it as vivid as ever.

He shrugged into his jacket, medals and metal clinking dully, closing each button with a firm movement as he stared at the window, thinking of nothing except the day to come and how to get through it. A step at a time, he knew. One after the other. Head down, back bent, eyes no more than two steps ahead, step after step until the day was done. He cinched a wide leather belt around his waist and took his cap from a hook on the wall and his pistol from the tabletop, sliding the gun into the holster with a dull rasp of metal on leather. Looking in the small mirror behind the door he adjusted the fit of his cap, then stuffed a pack of Atikahs and some matches into the pocket of his jacket and opened the front door.

‘All right, let’s go,’ he said, as he locked his door. Claussen straightened, his eyes flicking to the Iron Cross pinned to the left breast of Reinhardt’s tunic and back to Reinhardt’s face. He saw the change come across Claussen’s eyes as a decorated captain in the Abwehr came out of the room a half-drunk, half-dressed man had gone into.

Claussen led the way downstairs and into the cobbled length of the central courtyard of the Bistrik barracks, built by the Austrians at the start of their occupation of Bosnia at the end of the nineteenth century. They walked to a slope-nosed kübelwagen where a soldier was smoking a cigarette. He stubbed it out and saluted Reinhardt, his eyes looking up and over the captain’s left shoulder. ‘Corporal Hueber reporting, Captain,’ he snapped. He was tall and raw-boned, cheeks flecked with acne.

‘Hueber is our Serbo-Croat specialist,’ said Claussen as he opened the kübelwagen’s door for Reinhardt. ‘Major Freilinger said to bring a translator, just in case our Croat friends decide to forget their German.’

‘At ease, Corporal,’ said Reinhardt. ‘You speak the language?’ Reinhardt had picked up something of the language in his two tours in Yugoslavia. More than enough to follow the gist of conversations, order drinks, and scan the headlines of what passed for newspapers. He shook a cigarette from his pack and put it in his mouth.

‘Yes, sir. My mother’s family was from Zagreb.’

‘Carry on, then,’ he said, settling into the car. The other two climbed in, and Claussen engaged first with a grind and steered them past the sentries in their striped pillboxes and into the street. Reinhardt wedged his shoulders against the rim of the door and put his arm along the central bar behind the front seats, his hand resting on the empty weapons racks. Remembering the cigarette in his mouth, he lit it, drew deeply, exhaled, then after a moment’s consideration offered cigarettes to Claussen and Hueber.

Claussen drove over the Latin Bridge to Kvaternik Street, the old Austrian Appelquai, then followed the trams down to Vijećnica. They travelled past the jumbled Oriental warren of Bentbaša with its uneven cobbled streets and Ottoman houses with white walls and red roofs, and back through the city, past Baščaršija with its cafés dotted around its cobbled sweep. The air was cool this early in the morning, underlaid with the smell of coal and wood smoke, but the clear skies promised another scorcher of a day. Up at the top of Vratnik hill, beyond the jumble of roofs and minarets, the white walls of the old Ottoman fortress stared blankly down on the city.

‘What more did Freilinger tell you?’ asked Reinhardt as Claussen sped up again down King Aleksander Street. The city’s latest masters, the Independent State of Croatia – the NDH – had renamed it Ante Pavelić Street after their version of the Führer, but everyone, even those in charge, still called it Aleksander. At a crossroads, Ustaše policemen – Croatian fascists in black uniforms with rifles strapped across their backs – were pulling down Communist Party posters that must have been put up overnight. The walls on both sides of the road were covered in scraps of white paper where dozens more had been pulled down. More Ustaše stood guard over a group of men kneeling on the pavement with their hands on their heads. Two bodies lay in the street.

Claussen squinted around the cigarette smoke spiralling up into his eyes and slowed to bump the car over a bad patch of road. ‘The major only said the murders had occurred at an address in Ilidža.’

‘Ilidža?’ said Reinhardt. ‘That’s a bugger of a drive. And I need something to eat.’ He scanned the road ahead and motioned for Claussen to pull over while he jumped out and bought kifla off a trader in baggy black trousers and a red waistcoat pushing a handcart. The man kept his head down, his eyes sliding over him and past, as if around an absence, but Reinhardt was used to that now.

The bread was warm, soft, and salty-sweet as he chewed and watched the city go by. Down past the gutted ruin of the Sephardic synagogue, past the yellow arches of the city market, past the Imperial façades of Marijin Dvor and the old State House where the general staff had its offices, past the tobacco factory, the white exterior of the National Museum, and the long stretch of wall that hid the Kosevo Polje barracks, and then they were leaving the main part of Sarajevo behind and driving almost due west, the Miljačka valley opening out to north and south.

There was space here you never seemed to find in the city’s hunched streets. Orchards and fields running away from the road in long rectangles, the rolling countryside speckled with the four-sided roofs of traditional houses. The old Austrian road was dotted with horse carts, donkey carts, sheep and goats, tradesmen, farmers, women in twos and threes wearing long veils who turned away as the car went past. At the other end was the spa resort of Ilidža, nestled at the foot of the forested swell of Mount Igman, a sort of smaller, cleaner, more spacious counterweight to the city that lay behind them all squeezed in and jumbled up the slopes of the mountains that pinched off the eastern end of the valley.

The drive was a fairly long one, and despite the best efforts of the engineers, the road was not standing up well to the constant pounding of the military traffic along it. Claussen was forever slowing, braking, and swerving around ruts and potholes, but the drive gave Reinhardt time to think, time to recover from his binge, and time to start feeling ashamed of himself. He found his fingers again brushing over the spot on his head to which he had put the pistol, his mind opening again to the emptiness he struggled each night to encompass. With an effort, he tamped down on it, pushed it away, but it was becoming harder not to let the depression and despair he felt at night overwhelm him during the day. Again, he caught Claussen looking at him out of the corner of his eye, and he clenched his right fist tight and held it on his leg.

He tried to think instead about the victim, Hendel. In Sarajevo for three months or so. Prior to that with the Abwehr in Belgrade. He did internal army security and before that was in technical work – radios, cameras and such. Spoke the language fairly well, Reinhardt recalled. Liked the ladies and got out on the town whenever he was off duty. That was pretty much all he knew about him. He could not talk to either of the men with him in the car about anything Hendel might have been working on, so he put his head back and closed his eyes.

He must have dozed off to the vibration of the car because Claussen woke him up as they arrived in Ilidža. Reinhardt’s mouth felt thick, but the few minutes’ sleep he had snatched seemed to have refreshed him. Claussen turned left at the crossroads in front of the Hotel Igman, another of the Austrians’ neo-Moorish constructions, and continued south. Past the twin Austria and Hungary hotels, staring at each other across the round sweep of their lawn where an old gardener in a white fez watched them go by. Several staff cars were parked on the drive in front of the Austria, big, shiny vehicles with pennants at the front and motorcycle escorts. Just after the hotels, Claussen turned onto the beginning of the long alley that led up to the source of the Bosna River. The alley was bounded on both sides by rows of platane trees and by large, elegant villas standing on swaths of lawn. Ahead, on the left, several cars were pulled over between the trees or on the shoulder. A policeman approached as they drew up.

‘Tell him we’re here to see Major Freilinger,’ said Reinhardt to Hueber. The corporal leaned forward in his seat and spoke to the policeman who saluted and motioned them forward. Claussen pulled over behind a Mercedes with Army plates. Beyond that was a pair of local police Volkswagens and an ambulance with a driver behind the wheel.

‘I’ll go in and find Freilinger,’ said Reinhardt to Claussen. ‘Take Hueber and see if you can find the chief uniform in charge here, or the unit that responded first. See what they know.’

‘Sir,’ said Claussen. ‘On me, Corporal.’ Reinhardt walked over to the gate in the wrought-iron fence that surrounded the house. Built in the Austrian Imperial style, it had cream-coloured walls and two floors above the ground floor. A garage was built on one side of the house, its doors open and a white sports car just inside. A motorbike and sidecar with German Army plates was parked against the wall to the right of the front door, where a policeman stood guard. He was clearly unsure whether to let him in or not, so Reinhardt fixed him with his eyes and nodded to him as he went past and into the house, ignoring him but with his back suddenly tensed, as if for a blow.

Forcing himself to unwind, he stood for a moment with the light breaking to either side of his shadow. The hallway was dim after the clear day outside and he gave his eyes a moment to adjust, removing his cap as he did so. A staircase curved upstairs at the end of the hall, and doors opened off the hallway to the left and right. Framed photographs hung on the walls. From somewhere towards the back of the house, he heard the clink of china and a woman crying.

The wooden stairs creaked solidly under his weight as he went up towards the sound of voices. He breathed deep just before he reached the top and felt it, a gag that pinched the back of his throat as he caught the smell of putrefaction. Breathing slowly, Reinhardt tucked his cap under his arm and walked up the last few stairs.

The stairway opened into a living room, sumptuously furnished, a sofa and armchairs in warm brown leather gathered under a chandelier of washed blue glass. There was a low coffee table, with a bottle of French brandy and two tumblers, atop an Oriental-looking carpet. Two doors led off from the room, to the left and right. Directly in front, cabinets and tables in dark wood lined the walls beneath and between tall windows, and a clock kept soft time on the marble mantelpiece below a huge mirror in a worked gold frame. A portrait photograph of a man in a black uniform stood next to the clock, with a black band running laterally across the bottom right corner.

More Oriental carpets were laid out in other parts of the room, some of them rumpled, stained with the alcohol that had run from the bottles smashed across the floor from where they had fallen out of the drinks cabinet, itself lying facedown in shards of glass. A lamp on the floor, pokers strewn around the fireplace. One of the leather chairs askew, out of line with the others. And everywhere, lingering underneath it all, incongruous in this setting of refined luxury, was the smell of death.

Hendel’s body lay just to the right of the stairs, against the wall, with its torso slumped partly upright. A spray of blood and something darker had dribbled and dried down the wall above his head. He had been shot just below the nose, and from the burn marks around the wound the gun had been placed against his skin. Reinhardt’s right hand began to rise again of its own volition towards his temple and to the mark his own pistol had made there, but he covered it with a move to adjust the tuck of his cap under his other arm.

There was another smear of blood on the wall next to the door to the left. Freilinger was standing by that door with a big man in a dark but ill-fitting suit, both of them looking into the room beyond, which seemed to be brightly lit. Freilinger turned and saw Reinhardt standing by the hallway door. The major’s bullet head of close grey hair almost glowed in the strong light. As Freilinger’s eyes met his, Reinhardt suppressed a flinch at the sudden smell of smoke, there and gone just as fast. Swallowing, and looking left and right, Reinhardt walked across the living room, the parquet squeaking under his steps. His feet crunched on glass. Looking down, he saw a crescent of broken bottle with a Hennessy label, gold on black, like a piece of flotsam on the parquet floor.

Freilinger and the other man stepped away from the door, motioning Reinhardt over to the fireplace between the two tall windows. Glancing left, Reinhardt looked into a bedroom, saw part of a huge four-poster bed hung with silk, dark wood floors. He turned back to the two men, came to attention.

‘Reinhardt reporting as ordered, Major.’

‘This is Chief Inspector Putković, of the Sarajevo police. We have a problem, Reinhardt,’ said Freilinger, getting straight to the point as always. Freilinger had always maintained some distance between himself and Reinhardt, despite the common connection they had in Meissner, going back to the first war. ‘A double homicide, and one of the victims an army officer. Not only that, but an officer in military intelligence.’ He spoke quietly, his voice underlaid by a low, hoarse rasp, the legacy of a British gas attack in the first war. Speaking was painful for him. ‘This causes some jurisdictional problems, as you can well imagine, but I think the inspector and I have been able to come to a suitable arrangement.’

The inspector in question did not look like he felt a suitable arrangement had been reached at all. The man was big, in the way so many men in the Balkans seemed to be. Lots of fat on large bones. A taut paunch sagged over his belt, and his fists were like hams, the knuckles indented in the flesh. A porcine face, flat eyes that looked like anvils. He smelled of sweat and alcohol. ‘There is no need for German involvement. My men can handle this.’ His German was good, although heavily accented. He spoke to Freilinger, but his eyes bored into Reinhardt. ‘We are professionals.’

‘Quite frankly, I don’t care, and I’m getting tired of saying it,’ rasped Freilinger. Putković’s face went florid with his anger. ‘There are agreements and protocols for this sort of thing. I don’t care who the dead girl is. A German officer is dead. The two seem to me quite obviously to be linked together, however much you might not want them to be. You’ll work with Captain Reinhardt, who, I will remind you, has nearly twenty years as a detective in the Berlin Kriminalpolizei. Homicide and organised crime.’ He paused for breath but raised a hand to forestall the next protest from the Croat. ‘You will extend him every courtesy required. If you still wish to debate this, tell your commander to take it up with the general. Otherwise, we’re done.’

Putković’s jaws clenched. He stuck out his jaw, nodded, and then started for the stairs, clattering down them and hollering something to someone on the way out. Freilinger breathed out, shaking his head and putting his hand on the mantel of the fireplace. ‘God, what a bore.’ He looked up at Reinhardt. Freilinger was a small man, wiry, with piercing blue eyes. His skin was leathery and creased from a lifetime of soldiering. ‘This is no picnic I’ve landed you in, Reinhardt.’

‘No, sir.’

‘What do you have going at the moment?’

‘Third round of interrogations of the Partisan officers captured after Operation Weiss.’

‘Still?’

‘It’s the way I work, sir,’ wishing, as always, he did not sound so defensive about it.

Freilinger stared down at the carpet. ‘Very well,’ he said. ‘Hand them over to the camp authorities.’

‘Sir, I’m not finished with them.’

‘You are now. You won’t have time for them anyway.’ Freilinger lifted his eyes, flicked them around the room. ‘The reason I want you on this is Hendel was one of ours, and we keep this investigation close. I’m having Weninger and Maier go over his files, see if anything pops out that would link him to the dead girl.’ He paused as he took a small tin of French mints from his pocket, which he swore were the only thing that helped his throat, and popped one in his mouth. It was, as far as Reinhardt knew, the only habit or vice he had. ‘The dead girl is Marija Vukić.’ Reinhardt’s eyes widened. ‘You’ve heard of her?’

‘Marija Vukić? Yes, I have. I even met her once.’

‘Sort of a cross between Leni Riefenstahl and Marika Roekk?’ Reinhardt shrugged, nodded. ‘A filmmaker. A journalist. Well connected. And with a film star’s looks?’ Reinhardt nodded again, remembering the one time he had met her, and the impression she had made on him. ‘The Croats want whoever did this to her for themselves. I’m not sure they’re too bothered about Hendel, but if they can find a way to embarrass us with his death, they’ll probably try. They already have their list of usual suspects. I don’t doubt they’ll be breaking bones down at police headquarters fairly soon.’

‘I can perfectly understand the Croats’ preoccupation with finding the killer. Are you saying we’re in competition for suspects?’

‘Possibly. Possibly not. Maybe Hendel was killed after Vukić. But on the bright side, Putković has agreed to have Hendel examined by the police pathologist. It’ll save us time. We’ll know more then.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Reinhardt nodded, feeling a sudden sense of trepidation. In the hollow at the base of his spine he began to sweat. ‘Sir, shouldn’t the Feldgendarmerie have this one?’

Freilinger stared at Reinhardt, his chin moving as he rolled the mint around inside his mouth. ‘I’ll make sure the military police know you are leading this investigation, and that they give you whatever assistance you require. They’ve got enough on their plate with Operation Schwarz coming up, I would think. All eyes and effort’s going to be on that, on prising the Partisans down from out of their mountains and smashing them once and for all. And, like I said, Hendel was one of ours. We’ll take care of it.’ He paused, his fingers rubbing his throat. Thumb on one side, forefinger on the other. ‘I don’t know who the police’ll give you to work with, but try to be civil, and try to be quick.’ A swallow, the mint clicking against his teeth. ‘No one’s pretending the “Independent” in NDH means anything anymore. Especially now that just about every soldier they ever had that was worth anything is dead at Stalingrad.’ If he noticed Reinhardt’s discomfort at the mention of that city, he did not show it. ‘Relations are tense. Let’s see if we can’t keep these on an even keel.’

‘I’ll do my best, sir.’ Freilinger nodded. ‘One thing, sir. You do know that I haven’t attended a crime scene in over four years?’

The major looked back at him, his blue eyes like chips of glass, and a sudden flare, like a fire, deep within them, and again there was the smell of smoke in his nose. ‘That will be all, Reinhardt. I’ve assigned Claussen to you. He’s Abwehr, so you can talk freely with him. He’s also ex-police. He’s a resourceful man, and even if he does not look that way now you’ll appreciate having a friendly face around. Report to me at the end of the day.’

‘Do I wait for Putković’s man before starting?’ The major walked to the window over the alley. Heated words were being exchanged out there.

‘I’m guessing Putković’s man is being briefed now.’ Reinhardt looked down at the big detective talking loudly with a handful of policemen, one in a suit. Putković emphasised whatever points he was making by slapping one fist into the palm of the other. Even from up here, Reinhardt could hear the meaty thud they made. There was a space around the man the others would not, or could not, enter. Not surprising, given the animal ferocity the man gave off. Freilinger shook his head. ‘Get going. Let them catch up.’

With that, he was gone. Standing alone, Reinhardt put his hands on the mantel and breathed deeply. He hung his head down between his arms, feeling the strain in the back of his neck. His headache was still there, heavy along the base of his skull. He looked at the portrait. A father? An uncle? A quick breath, and he stepped into the bedroom.

2

A middle-aged man, very thin and white, sprawled in a chair in a corner, polishing his glasses on his tie. He blinked owlishly at Reinhardt and said something in Serbo-Croat. ‘German,’ replied Reinhardt in German. The man put his glasses on, spotted Reinhardt, and half raised himself from the chair.

‘Sorry,’ he said, sitting back down. ‘Dr Begović.’ He appraised Reinhardt with an openness strangely refreshing from someone in a city where most people would not meet your eyes, and those who did always seemed to find something wrong with you. ‘Forgive me for not getting up, but I’ve been here for hours now.’ He scratched the corner of his mouth. ‘You’re the one they’ve been arguing about, eh?’

‘It would seem,’ replied Reinhardt, distantly. He mentally pushed the doctor aside and remained in the doorway. The bed was a big four-poster, directly in front of the door. A black dress made a crumpled ring on the floor at the end. There was a dresser with an oval mirror and upholstered stool against the wall to his left. Closed curtains ate the daylight along the wall to the right, but the light in the room was still very bright. There were two little tables on the end of the bed nearest him, on which rested two lamps, which were lit. Lights fitted into the wall to either side of the door were also lit, and the head of the bed was a big mirror. He saw himself reflected in the doorway and saw another big mirror hanging on the wall to his right.

His nose caught a subtle hint of fragrance, something expensive, under the heavy smell of blood, and the smell of death, which was much stronger here. The red stain on the door frame, a smear of blood across a panel of light switches, caught his eye. He saw another, a footprint, a third, a smear on the door of what he saw was the bathroom across to his left, as though a hand had reached for balance and slipped and slid. He breathed deeply, and Begović looked from him to the body on the bed.

‘Not pretty, is it?’ he said, with an ironic twist to his mouth.

Reinhardt’s heart began beating faster. He took a couple of steps closer to the bed and looked down at what was on it. ‘No, it’s not. So. Why don’t you tell me what we have here?’ he asked, with a nonchalance he did not feel.

Begović took off his thick-framed glasses and rubbed his watery eyes with the heel of his hand. Putting them back on, he blinked furiously, peered at Reinhardt, sniffed, then looked down at a notebook he pulled from a pocket. ‘What we have is a dead female, aged twenty-five to thirty years, deceased from approximately eighteen stab wounds to the stomach, upper chest and upper arms. In addition, there are signs of severe beating, strangulation marks around the neck, hair missing. There is blood and tissue under the fingernails, bruising on the knuckles, so she fought back. What little good it did her.’

Reinhardt nodded, listening to Begović reel off the horror that had happened to this woman. It did not do justice to what he saw laid out on the bed in front of him. Reinhardt remembered Marija Vukić as a stunning woman, statuesque, blond, a woman of grace and elegance. She still was, despite what the beating had done to her face, and the knife to the rest of her. Her eyes still kept a clarity of blue behind the veil that death had drawn over them. Her long blond hair still retained a sheen of gold despite its lying in matted disarray across sheets sodden red with her blood. Her skin, though, was ghostly white, the wounds the knife had left crusted and raw edged. Her limbs were long and straight, her legs gorgeous in black stockings, a garter belt around her narrow waist. She lay on the bed as if at rest, head on the pillow, arms at her sides, her legs drawn straight and together. The remains of a silk negligee, shredded and soaked in blood, lay rumpled about her torso.

As he ran his eyes over her, over what had been done to her, Reinhardt felt a peculiar sensation, a sort of fulfilment of an almost-forgotten imagining of what she might look like unclothed. Whatever it was, it felt wrong, but he recalled dancing with her, just the one dance, feeling her pressed lightly against him, her breast against his arm, her thigh against his.

‘Your German is very good, Doctor. Murder weapon?’

‘Thank you. Medical studies in Berlin in the thirties. A knife. A big one. Very sharp. Something like a kitchen knife, or a bayonet.’

‘Has it been found?’

‘Not that I’m aware of.’

‘Time of death?’

‘At a guess, I’d say sometime late on Saturday night.’

‘Did you look at the other body?’

‘Briefly. I was told to concentrate on this one. But I’d have said he died about the same time.’

‘Has forensics had a look at her, yet?’

Begović snorted. ‘Forensics?! Seriously? In this town? This isn’t Berlin, my friend, and we aren’t the Kripo.’

‘Right,’ Reinhardt breathed. What the doctor said would have been true of the Kriminalpolizei about ten years ago, but not anymore. He raised the dead woman’s arm by placing his wrists above and below hers so as to avoid leaving his own prints and saw the telltale marks of lividity underneath and on what he could see of her back. Reinhardt bent her arm, and it moved fairly well. Rigor mortis had come and was mostly gone. Begović was probably right with his guess, but they would need the pathologist to be sure.

The sound of someone taking the stairs two by two came from the other room. There was a pause as the person reached the top, and then the sound of the parquet as he came over to the bedroom. Reinhardt turned as the man in the suit he had seen from the window entered the room. Another tall man, but without Putković’s weight. He had longish brown hair, and dark, flat eyes. He glanced over the room and at the two of them standing there. His mouth firmed, and he stepped inside the room. ‘You are Reinhardt?’ he said. ‘I am Inspector Andro Padelin. From the Sarajevo police. My chief informs me we are to work together?’

‘That’s correct.’ Reinhardt stepped over to shake his hand. Not a small man himself, Reinhardt felt his hand enveloped in the other’s fist and squeezed, relatively hard. All the while Padelin looked at him with those dead eyes. It was he who let go, with a slight push, and the faintest of glances up and down, from Reinhardt’s boots to his greying hair. ‘Have you been briefed?’ Padelin nodded. ‘The doctor here was just giving me some insight into the wounds the woman sustained.’

Padelin turned those heavy eyes on the doctor, who did not seem perturbed. Probably because he had his glasses off again to polish them. ‘Yes. Well, it would have been courteous to wait.’

‘Shall we hear what he has to say, then?’ asked Reinhardt. Padelin nodded, slow and heavy, like a cat sunning itself. ‘Doctor, if you please?’

Begović cleared his throat. ‘Well, for what it’s worth, whoever did it was probably left-handed. Probably. That’s from the pattern of the wounds. The stab wounds go from her right to her left. The slashing wounds from her left to her right. And she received nearly all her wounds here, in this room and on the bed.’

‘Slashing and stabbing…’ said Reinhardt, quietly. ‘What does that tell you, Doctor?’

The coroner stared at her arm where it sagged stiffly over the side of the bed, the palm and fingers dark with blood. ‘I would guess from the depth of the wounds that whoever did it was not very strong. But from the spread of the wounds, the killer was slashing and stabbing wildly, maybe in a great hurry, or was deranged, or had strong reason to hate her. Maybe a combination of all.’

Still staring at the body, Reinhardt shook an Atikah from his pack and put it in his mouth, before offering the pack to Begović and Padelin. The detective refused with a shake of the head, while Begović pounced eagerly on his cigarette, rolling it delicately between his fingers before letting Reinhardt light it. The flare from his match woke answering glints in Vukić’s eyes, and the memory of dancing with her under a spreading chandelier came to him again. A Christmas dance, just a few months ago, for the officers of the garrison, the city caked in snow and ice. She had smiled and laughed, joked and cajoled, given as good as she got with the banter, posed for photographs, danced with them, then left, all light and movement, and a scent that glittered. A smell of tobacco tangled with the iron scent of the woman’s blood, clamouring across the memory of that evening. Reinhardt swallowed and took a little round tin from his hip pocket, into which he tapped his ash.

‘He beat her, then stabbed her?’

‘Could be,’ said Begović, around a deep drag. He tore a page from his notebook and crumpled it in his hand to serve as an ashtray.

Reinhardt stared at her. At the rumpled sheets. A champagne glass with a thick smudging of fingerprints stood on a bedside table. On the other side of the bed, on a similar table, was an ashtray with a number of stubbed ends. ‘Was there sex?’ As he moved slightly, the surface of the table caught the light. A ring mark, faint and almost faded.

‘Dressed like that?’ Begović quipped. ‘I would certainly hope so.’ Padelin snarled something at him in Serbo-Croat. Begović sat up a bit straighter in the chair and answered back, but Padelin cut him off. Begović sighed and switched back to German. ‘I don’t know. I can’t tell. The pathologist will know, soon enough.’

‘You said most of the wounds she got here on the bed. Where did it start? The stabbings, I mean.’ Reinhardt got down on his hands and knees to peer under the bed, squinting around the curl of smoke that drifted across his eyes.

Begović stared down at Reinhardt’s back and pointed unnecessarily with his notebook to the foot of the bed. ‘There, I think. A spray of blood across the bed hangings. Find something under the bed?’ Padelin knelt to see what Reinhardt had seen. He straightened up.

‘And is a forensics team coming?’ Reinhardt asked Padelin.

‘Yes.’

Reinhardt studiously made a point of not looking at Begović, himself engrossed in watching the tip of his cigarette burn. ‘Make sure they know there’s a bottle and a glass, probably not the woman’s, under the bed.’ He looked around the room, at the drawn curtains and the lights. ‘Do you know whether the room was lit like this when the police arrived?’ he asked Padelin.

‘I can ask the maid.’

‘Please do,’ said Reinhardt. ‘Are you nearly finished?’ he asked Begović.

‘Yes. Why do you think it’s not the woman’s?’ asked Begović.

Reinhardt pointed at the glass on the table. ‘She lived here. Stands to reason she’d use the side of the bed nearest the bathroom.’

Begović nodded, his mouth making an O. ‘Well, I’m all done, unless you gentlemen need something else?’

Reinhardt looked at Padelin questioningly. The big detective shook his head. ‘Wait downstairs, please, Doctor.’

‘Shall we have a look in the bathroom?’ asked Reinhardt, as the doctor left. He dropped his cigarette stub into his little tin and pocketed it, letting Padelin go first, watching. The detective walked right in, standing in the middle of the room. Reinhardt paused in the doorway. It was lavishly equipped, with a huge white bath, gold taps, an ornate showerhead. Tiles in a repeating blue-and-gold motif ran around the room at waist height, and a mirror in a mosaic frame that looked Spanish hung over the sink. Toothbrush, toothpaste, French cosmetics on the white enamel sink. Towels and brushes on a set of tall wrought-iron shelves, from which hung a black silk dressing gown. And luxury of luxuries, a toilet with a shiny wooden seat.

Casting an eye around the room, Reinhardt spotted the blood marks on the wall on either side of the toilet, and a bloody towel wadded up and thrown into a corner. Large as the room was, Padelin filled the space with his bulk, watching Reinhardt with those dead, catlike eyes. Reinhardt peered into the toilet, but it was empty. Blood marks on either side of the sink, as if someone with blood on their hands had leaned on it for balance or support. He stared around the room once more, trying to imagine what had happened and what he might be missing. Putting his tongue between his teeth, he sighed, turned and walked out, back into the bedroom.

Padelin joined him there. ‘The maid is waiting to be questioned,’ he said, quietly. His German was slow and ponderous.

Reinhardt nodded. ‘I need to have a look at the other body first.’

‘You do that,’ said Padelin, in a tone that implied Hendel was all Reinhardt’s. ‘I will see what she has to say.’

3

Hendel had been poster-boy good-looking. Chiselled features, blue eyes, blond hair. The works. Looking up at the wall, Reinhardt could see where Hendel’s head had struck it, traced the long smear of blood the body’s sliding fall had left before it came to rest there, shoulders slumped across the skirting board, one ankle crossed beneath the other. Hendel was in uniform, but whoever had shot him had emptied his pockets and removed his rank insignia, hoping, Reinhardt guessed, to delay identification. It would have worked, if one of the Feldgendarmes who responded to the call had not recognised him.

For once, Reinhardt thanked Hendel’s habit of staying out late with the ladies and the number of times the Feldgendarmerie must have fingered him stumbling back to barracks late and drunk. He lifted Hendel’s leg by the boot. As with Vukić, the rigor mortis was almost gone. He could not have died much more than a day ago. Definitely about the same time as her.

Reinhardt walked across the living room and entered a study. To his left, a tall window looked out on the garden. Against one wall was a large, heavy-looking table, the wood worn smooth and rich with age, but he did not pay much attention to it because above it, and arranged haphazardly all over the wall, were photographs in black frames. In most of them, Marija Vukić stared or laughed or pouted out at him with an intensity that made his stomach suddenly clench, remembering how they had talked at that dance. Not for long, mostly about Reinhardt’s time in the first war, but for as long as he had talked she had listened with a particular intensity, blue eyes boring into his.

Marija in flying gear, posing next to the wing of an old biplane. Marija with her hair flying about her face as she looked down from the railing of a ship, an elderly man at her side. Marija swathed in robes and turban on a camel, two Africans either side of her. Marija at a table filled with people, the glare from the flash reflected in the glasses of champagne in front of them. Pictures of Berlin, Paris, Trafalgar Square almost blotted out by a flock of pigeons caught in the moment of lifting off. Places in Africa, in Asia. Pictures of people, Germans, French couples on café terraces, families picnicking on lawns, Japanese in traditional dress, Africans, soldiers.

Lots of pictures of soldiers. A man in an old Austrian Imperial Army uniform leaning on a rifle in a trench with his feet in water. A mutilated soldier slumped against a brick wall, outstretched hand holding a begging bowl. A picture of an officer on horseback. Columns of infantry, Germans, with slung rifles, blond hair blowing in the breeze. Reinhardt swallowed in a suddenly dry throat, eyes drawn back and caught by that soldier with his head down, begging. There but for the grace of God, he thought…

From downstairs came the sudden sound of a man shouting. Faint, beneath it, a woman crying. Frowning in distaste, Reinhardt looked away from the begging soldier and found himself staring at a picture of the Führer. Whoever had taken it had shot him through a crowd of uniforms, black sleeves, and swastikas, some with the Ustaše armbands, and all the faces were looking one way with expressions of anticipation and delight, but he was looking straight at the camera, away from everyone else, face utterly expressionless. Reinhardt shivered suddenly, turned his head away.

Down the other wall were shelves filled with books and objects, floor to ceiling. Reinhardt cast a cursory eye over them as he walked slowly over to the other door, which was closed. Taking a handkerchief from his pocket, he opened it slowly, pushing the door open onto darkness, a faint suggestion of surfaces and cabinets appearing out of the gloom, and a smell of chemicals that peaked and faded, as if it had just been waiting for the door to be opened. Peering around the door, he found the light switch, flicked it on. It was a darkroom, and it had been ransacked. Photos blanketed the floor, cabinet doors were open, a drawer lay on the floor. Bottles of fluid, brushes, clips, and string stood or lay strewn across work surfaces. A pair of scissors lay in an empty enamel sink.

‘Shit,’ muttered Reinhardt. He took a step into the room, knelt, and looked down at the photos scattered across the floor. Soldiers again, most of them. Modern photos, and recent as well, if he was any judge of uniforms. He brushed aside a photo to reveal one of what looked like Afrika Korps soldiers, men swathed in scarves and dust riding atop tanks in column and, for a moment, he was back there with them under that baking sun. Another one, Marija with goggles drawn down around her throat with a man in uniform, a minaret needling the sky behind them, a swath of sea the backdrop to it all. Frowning, Reinhardt leaned closer, then smiled in admiration. The man was Rommel, peaked cap, leather coat, binoculars and all, just as in the pictures. There were steps behind him, and Claussen came to a stop in the doorway.

‘Sir?’

‘A moment, Sergeant.’ Reinhardt straightened and ran his eyes around the room, over the jumble of pictures and paraphernalia that littered the surfaces. There was a cupboard under the sink with its door ajar, and something metallic glittered back at him. Stepping carefully, he reached out and pulled the door open wider. A couple of film cases, round tins of various sizes, stood haphazardly in a curved rack that was otherwise empty. The tins had been opened, and the beginning of each roll of film had been unwound, then put back. He reached in and took the end of the nearest roll between his fingertips and turned and lifted it to the light. He passed the strand of film through his fingers but it was blank. The rest of the rack, where there was space for a couple of dozen tins, was empty. He nodded to Claussen.

‘The uniforms told us the neighbour might have seen something.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Not really, sir, and I was free with the smokes. Hueber did most of the talking, but they’re being pretty close-lipped. Especially after that big fellow gave them a right beasting before he left.’

‘Yes, I saw that.’

Reinhardt looked around the room again. He doubted he would be back so whatever he needed to take in terms of impressions or conclusions from the murder scene, he needed them now. Taking a deep breath, he turned back into the study, looking down its length, running his eyes over the books in a half dozen languages, objects that looked like they had been collected in a dozen countries.

‘Bloody hell, sir,’ came Claussen’s voice from the darkroom. ‘There’s pictures of her here with about every general in the Wehrmacht. Guderian. Hoth. There’s one here with Kesselring. One with Goering…’ Claussen’s voice trailed off into muttered remarks.

Taking his handkerchief from his pocket again, Reinhardt opened the desk drawers one by one but saw no sign of anything that looked like an address book. Straightening, he looked back at the bookcase. On a bottom shelf, next to the door, he spotted a gap, books missing. Squatting, he ran his eyes over them. They were all of differing sizes and textures, but each one was carefully annotated along the spine with dates. He opened one or two at random. They were journals, or diaries. They went back a long way, until 1917, the later years covered by two, even three books. The writing was wide and childish in the earlier ones, closer and neater, denser, in the later ones. Pursing his mouth he stared at where the journals for 1942 and 1943 once were. Looking around, he noticed how much it resembled a man’s room, rather than a woman’s.

Claussen was standing not far away, seemingly absorbed in the picture of the begging soldier. Reinhardt straightened up. ‘Sergeant?’ he said softly.

Claussen turned and looked at him, then back at the picture. ‘You know, for a moment, I thought that it looked like a friend,’ he said softly. ‘Boeckel. Poor sod got most of himself blown off at Naroch.’ The sergeant shook his head, and Reinhardt left him to it, running his eyes over the room one last time and walking back into the living room.

Standing in the centre of the room he looked around, turning slowly, trying to imagine what had happened. There were two glasses on the coffee table. There was a fight. Someone kills the soldier. Takes Vukić into the bedroom, rapes her, beats her. Stabs her to death. No. That did not feel right. Besides, there were the champagne glasses in the bedroom. Vukić and whoever was with her, they took their time, had fun about it. So what went wrong? And why was Hendel shot, when Vukić was stabbed? He looked from the bedroom to Hendel’s body, the study, the ransacked darkroom. Back to the bodies, where Hendel lay sprawled across the floor, and Vukić, seemingly at rest on her bed.

Someone was looking for something, came the thought. Searching the study, the darkroom. But they heard a noise… He shook his head. It felt elusive, too light. Not enough evidence.

He turned as Claussen came into the room. ‘I’m going to go and find my new partner. Inspector Padelin.’

‘He’ll be the one giving the maid hell, would he?’ quipped Claussen. As they arrived at the stairs, Reinhardt paused, looking up as the sound of voices drew him down.

‘Sergeant, have a quick look up there. Don’t touch anything. Just see what’s there.’

The kitchen was as well appointed as the bathroom upstairs. On a chair in a corner, with Padelin looming over her, sat an elderly lady in a neat black uniform and a cleanly pressed and starched apron. Her hair was grey, tied up behind her head in a bun. She swallowed a sniff as he came into the kitchen and rose quickly to her feet, did a little curtsy. Reinhardt watched her the whole time, saw the fear shoved back in watery little eyes at the sight of him, but the urge he once had to reach out and calm people like her was long gone, quashed deep inside him. It only ever confused them anyway; people did not expect sympathy and understanding from people like him, not anymore.

He looked questioningly at Padelin, who looked down impassively at the maid. She shook her head, not able to look up at him and whispered something into a crumpled handkerchief.

‘She has told me what she knows.’

‘I look forward to hearing it,’ said Reinhardt. He glanced around the kitchen again. It was neat, tidy, smelling of polish and a faint smell of spices. The only thing drawing his eye was a padlock hanging from a tall cupboard door by the stairs. ‘Just ask her one thing, if you would. Does she know where her mistress kept an address book?’ Padelin rapid-fired a question at the maid, who peered at him over the ripple of her knuckles. She looked at Reinhardt as she replied, gesturing upstairs. She sniffed as Padelin answered for her, her eyes flickering back and forth between the two of them, hands clenched hard around her handkerchief.

‘Upstairs in the study. A red leather book.’

‘It would seem it’s gone.’

As the two of them went out into the hallway, Claussen came downstairs. Padelin looked hard at him, and then at Reinhardt. ‘Who is this?’

‘This is Sergeant Claussen. He is assisting me.’ Claussen nodded cordially at Padelin.

‘What were you doing up there?’

‘Checking the top floor. There’s nothing there, sir,’ he said to Reinhardt. ‘All the rooms have been closed up for a while. Sheets over the furniture. It hasn’t been cleaned in a while. My boots left marks in the dust, and mine were the only tracks up there.’

Padelin said nothing, only stared at Claussen. Claussen, unfazed, stared back. ‘And the ground floor, Inspector? What do we have down here?’

The detective turned his eyes slowly from Claussen. ‘Downstairs was the father’s apartments. The parents were divorced, said the maid. Father and daughter lived here. But he was killed last year by Četniks, and the maid said these rooms have not been used since then.’ He turned and went back outside.

Reinhardt and Claussen exchanged glances. ‘Sergeant, quickly, go upstairs and have a look at the bodies. Just look at them. I’ll ask you later what you think.’ Claussen nodded, and then Reinhardt followed Padelin out, holding back when the detective began talking to three uniformed policemen. Hueber was hovering nearby, and Reinhardt motioned to him to listen to what was being said while he went back over to their car.

Padelin gave a flurry of orders to his men, then came over to Reinhardt’s car. Reinhardt offered him a cigarette, which he again refused. Lighting his own, he waited for the detective to tell him what the maid had said.

‘The last time the maid saw Vukić was Saturday morning. She was asked to prepare food and drinks for Vukić and a guest. A man. She does not know who the man was, but she’s positive it wasn’t to be your officer. Hendel, she knew. This other one, she didn’t.’ Reinhardt took a deep pull on his cigarette and nodded for him to continue. ‘She has Sunday off. She came in this morning, found the bodies, and called the police. According to her, when Vukić wasn’t travelling, she kept a busy social agenda. Lots of parties and outings. People coming and going.’

‘Very good. So we need to find some of these friends. Talk to them. See what they know.’

Padelin grunted assent, those eyes flat, far back in his head. ‘That is for us, I think.’

Reinhardt pursed his mouth and stared at the ground. Not much to go on, his new partner already playing jurisdiction games, and they were the best part of two days behind the killer, or killers. He raised his head. ‘There is something I heard about a witness who might have seen something on the night of the murder?’