3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

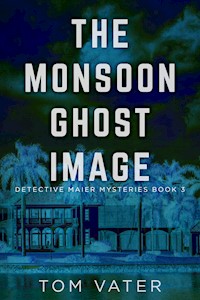

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Dirty pictures, secret wars and human beasts. Detective Maier is back to investigate the politics of murder.

When award-winning German conflict photographer Martin Ritter disappears in a boating accident in Thailand, the nation mourns the loss of a cultural icon. A few weeks later, Detective Maier's agency in Hamburg gets a call from Ritter's wife. Her husband has been seen alive on the streets of Bangkok.

Traveling to Thailand, all Maier finds is trouble and a photograph. But as soon as Maier puts his hands on the Monsoon Ghost Image, the detective turns from hunter to hunted. The CIA, a doctor with a penchant for violence and a mysterious woman known as the Wicked Witch Of The East all want to get their fingers on Ritter's most important piece of work.

From the concrete canyons of the Thai capital to the savage jungles and hedonist party islands of southern Thailand, Maier and his sidekick Mikhail race against formidable foes to discover some of the darkest truths of our time - and save their lives.

This book contains graphic sex and violence, and is not suitable for readers under the age of 18.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE MONSOON GHOST IMAGE

DETECTIVE MAIER MYSTERIES BOOK 3

TOM VATER

CONTENTS

Praise for Tom Vater

Other books by Tom Vater

1. Andaman Sea, Thai Territorial Waters, October 2002

2. Hamburg, Germany, November 2002

3. Berlin, Germany, November 2002

4. Bangkok, Thailand, November 2002

5. Hamburg, Germany, December 2002

6. Bangkok, Thailand, January 2003

7. The Good Doctor

8. The Bigger Picture

9. Burn Baby Burn

10. Health Scare

11. North-East of Heaven

12. Third-Party Collateral

13. Southern Thailand, January 2003

14. The House

15. The Bucket People

16. Wuttke

17. The Bad German

18. The Prisoners

19. Ritter’s Return

20. The Hunt

21. The Chase

22. Nomads

23. Maybelle

24. The Boat

25. Bangkok, Thailand, February 2003

26. Thailand, February 2003

27. Dagestan

28. Fuck You

29. Ginger

30. Bangkok, Thailand, March 2003

31. Doctor’s Orders

32. Southern Thailand, March 2003

33. Fun House

34. It’s a Trap

35. Stumble Through the Jungle

36. Soul Charge

37. Crawlspace

38. Hamburg, Germany, April 2003

Acknowledgments

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 Tom Vater

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Megan Gaudino

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

PRAISE FOR TOM VATER

“There’s a tremendous – and tremendously fresh – energy to Tom Vater’s writing.”

ED PETERS, THE SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST

“The narrative is fast-paced and the frequent action scenes are convincingly written. The smells and sounds of Cambodia are vividly brought to life. Maier is a bold and brave hero.”

CRIME FICTION LOVER

“This is noir at its grittiest, most graphic best. There is a lush complexity in the narrative that Mr. Vater has brought us readers. To say this was a historically laden story is to sell it short. We are transported into the world of Cambodia, and quite possibly one that most of us will never see in real life. The magic, the awe, the mystique and mystery all accompany the depth of characterization.”

FRESH FICTION

“The Cambodian Book of the Dead is an enigmatic, unsettling thriller that never lets you get your balance.”

CHEFFOJEFFO

“Exuberant writing.”

ANDREW MARSHALL, TIME MAGAZINE

OTHER BOOKS BY TOM VATER

The Devil’s Road to Kathmandu

The Cambodian Book of the Dead (Detective Maier Mystery, Book 1)

The Man with the Golden Mind (Detective Maier Mystery, Book 2)

Kolkata Noir

Sacred Skin (with Aroon Thaewchatturat)

Burmese Light (with Hans Kemp)

Cambodia: Journey through the Land of the Khmer (with Kraig Lieb)

To Scott,

Thanks for the good times on the road, the sage advice on the first two Maier books, & the friendship… I wish you could read what happens next.

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand.”

ANSEL ADAMS

ANDAMAN SEA, THAI TERRITORIAL WATERS, OCTOBER 2002

THE CARABAO

Martin Ritter was ready, as ready as he’d ever be. Ritter was ready to die.

He’d collected and paid his debts. He’d made peace and hard choices. In a few moments, the ocean would take him away, into its impenetrable depths, or into a new life. The thirty-eight-year-old combat photographer was calm and focused. He’d played the life lottery many times, had stared into the abyss over and over, and had reemerged, loaded with tales of horror, triumph, and despair. Congo, Cambodia, Afghanistan, he’d seen it all. This was just another trip to the bottom of everything.

There was no land in sight, no matter which way he turned. The sun was about to come up and the slight breeze, fresh and salty, would presently give way to merciless tropical heat reflecting off the water from here to the edge of the world. He’d prepared everything and now stood at the stern of the Carabao, the luxury fishing yacht that had got him here, amongst neatly coiled ropes, buckets for the burley, and the seat which his best friend and assistant Fat Fred had broken a couple of days earlier while trying to pull a huge marlin from the great wet.

Deep sea fishing could be so much fun.

But Fat Fred had caught his last fish. Ritter’s life was compromised. He’d made the deal at the crossroads and all who’d traveled with him had to go. It was time for a purge. The common term describing the likely fallout from Ritter’s next move was collateral damage.

A few years earlier, in the wake of civilian killings in Kosovo, a bunch of German linguists had named collateral damage the un-word of the year. Too right, Ritter thought. Yet everyone was living in an un-world, talking to each other in un-words. Most people just didn’t know. Anything. He knew. He was about to kill seven people, including his corpulent friend.

He knew.

He inhaled deeply and tried to listen to his inner voices. There were none. He was calm enough, all things considered. He’d never killed anyone. In fact, he’d saved quite a few lives in his time. Perhaps now, things would even out.

The point of arrival and the moment of departure were close. Martin Ritter was ready to let go – of his career, his friends, his routines and aspirations, his half-baked ideas about life and love and justice and the loss thereof, all the big questions. He was ready to let go of Emilie.

Even of Emilie.

This was radical stuff. In some ways, he’d be killing her too. And he was ready to let go of everything he’d seen through his view finder.

He smiled vaguely into the dawn and took stock the way his father, a reliable accountant from Düsseldorf, would have done.

Martin Ritter had been one of the good guys, one of the heroes of his time, a familiar face on television, a man who encapsulated the Zeitgeist, a winner. He’d taken great risks and had done great things. He’d witnessed history in all its beauty and terror and then some. He’d rolled with more punches than the great Ali and he’d enjoyed his victories.

At the height of his career as one of the world’s most committed conflict photographers he’d loved and married a great woman. And yet, despite all the tales of heroism and the ensuing success, financial and otherwise, he had, as only a post-war German could, fastidiously held on to the fact that he was but one tiny cog in a giant matrix, a player with an exaggerated sense of self, stumbling through an age that had begun to frown upon the cult of individuality.

Had he been American, he might have believed that his work, discovering and documenting ugly truths, would be a modest but important contribution to the greater good, part of a valiant effort towards stopping all wars. But he was German, blighted and liberated by his particular history.

Martin had been photographing war and misery around the world for two decades. Stern, The Süddeutsche, TAZ and Bild, TIME, Newsweek, The New York Times, The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, he’d worked for everyone.

He’d been thrown out of countries by killers trying to hide their crimes. He’d been beaten by ordinary men on fire. He’d portrayed the down-trodden and poor as well as the cruel and the powerful. He’d dined with presidents and common garden variety torturers, with queens and with anti-queens. Sometimes it had been hard to tell them apart.

He’d traveled to the very heart of things that concerned people, all people, in all countries and cultures, that dark heart. He’d been down to the wire of common notions of success and decency, of fear, terror, and sublime elation. A life in images, assignments, war, corruption, nepotism, murder, and more awards than he cared to remember. Mansions made of mud had piled up inside him and around him, had filled with useless thoughts that had fragmented and washed away.

Ritter had been a reasonably honest man, a man of ideals and principles, but it hadn’t been enough. His paradise was a featureless place, the absence of most things, much like the tranquil water of the Andaman Sea around him. Martin Ritter was tired of the high wire act. His hard drive was full, his emotional operating system dated and corrupted. He would crash or burn.

Despite his best efforts to help, to point, to cry, and to live, the world hadn’t changed, only he’d gotten older, wiser, and less knowing. His long-held certainties had faded and every time he now pressed the shutter, it was as if casting a small stone into an expanse of water as immense as the one around him, watching the ripples the splash made extend a few metres towards infinity and then quickly fade into silent, blind insignificance.

He looked out across the calm water, half hoping for a storm, a typhoon, a huge wave, anything to carry him overboard and away from the traps he’d set for himself and jumped into, more or less consciously and always wholeheartedly.

That’s what happened in life.

But not this time. He’d walked into traps before, eyes wide open, convinced of his righteousness. This time, the last time, he’d bent it as far as he could without breaking it. Perhaps his certainty was a tad overplayed. But the thought passed as quickly as the bird that fluttered above the placid, dark ocean, not quite decided on a resting place, even as the Carabao was the only solid opportunity visible.

As he leaned over the side of the boat, he spotted his reflection, distorted by the languid movement of the water and by his recent actions, his last assignment. His face flickered back at him, part handsome hero, part ugly other.

Martin Ritter looked at the GPS data on his watch again. The water was deep, almost a mile deep. He’d mapped out the currents and discreetly packed water and food for a couple of days. The next fishing boat wouldn’t be far. He had a flare gun. It was a risk, a risk worth taking.

The crew was still sleeping in hammocks towards the bow of the Carabao, snoring in semi-unison, oblivious to his plans. With a last look around, he strapped on a weight belt, pulled the fins over his rubber shoes, took a deep breath, and then let himself slide over the railing in silence, making sure he held his cell phone above the waterline. As he drifted away from the boat, he zipped up both his wetsuits, pulled the mask onto his face, and pressed the call button. Then he dropped the phone into the ocean and dived straight down, as far into the dark void as he could.

The ocean shook briefly.

The Carabao combusted in a roaring fireball, shooting fiberglass panels, fishing rods, and scuba bottles into the faint morning sky as if loosening a celebratory firework display upon the world that found no audience.

By the time Martin Ritter resurfaced, the waves and ripples caused by the explosion were dissolving into the vast, featureless mass of water around him.

He was alone.

He was alive.

HAMBURG, GERMANY, NOVEMBER 2002

MAIER

Maier felt like shit. He stared up at the pale, German afternoon sun pouring through his bedroom window, a sickly disc filtering through the haze of Altona and too many Camparis barely diluted by the night before. And the night before that. And…

Maier recalled that Campari Orange, to which he’d been introduced by a worn transvestite from Magdeburg who’d lost an ear and a half to a gang of Neo-Nazis, was his new favorite drink. A drink made from crushed insects, sweet at first and then bitter, and finally sweet again, just like that series of moments he called his life. Forty-eight years of life.

He’d also discovered that he had a soft spot for transvestites.

Oh, fucking dear.

Maier was down.

Detective Maier hadn’t worked in six months, not since he’d slept with his stepsister. Not since his father had tried to kill him. Not since he’d lost a couple of fingers in an ambush on a Vietnamese prison camp in the jungles of northern Laos.

He’d been trying, halfheartedly, to get out of the desperate corner he found himself in, but the deck was stacked. Every morning he woke up surprised to have lived through the drink and sweat sodden night and a familiar process of deconstruction started anew.

He read the papers and hated the world. Why solve a crime when everything he read about was criminal?

Maier had been trained to be a political animal. While he’d never been enthusiastic about the communist propaganda he’d grown up with, he’d absorbed it and it had shaped him. His political sensibilities had their origins in his Cold War Eastern German youth and young adulthood, but those old certainties had long gone.

He’d worked as a foreign correspondent for the state-owned GDR media until the Wall had come down. Then he’d worked for West German media, on the road, out of hotel rooms both shabby and sumptuous. Assignments from Cameroon to Mallorca. A couple of years of that and he’d started to get bored.

He’d joined the Deutsche Presse-Agentur, better known as DPA, and by the mid-90s, Maier had begun to drift through most of the dirty little wars of the late 20th century – from the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories to the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia and the high-altitude conflict in Nepal. But he’d left it all behind when he’d lost a Cambodian friend to a Khmer Rouge bomb five years earlier. He’d wanted nothing more to do with war.

And now it was all around him.

The twin towers had tumbled. A clear demarcation line had been drawn in the collective narrative of the brotherhood of man. People weren’t arguing about issues anymore. People were arguing about what had happened and what was happening. People were arguing about the course history had taken and was taking, about who was writing it and how it was being broadcast and consumed, and they no longer agreed on the broad strokes. The truth was becoming just another story. For better or for worse, certainty was fragmenting. A hard bread for a German whose world had already fragmented.

Maier could hear the war drums without getting out of bed. He could feel the ripples of the attacks in New York expanding on and on, to the four corners of the world, to the rim of infinity. He could feel them because he had no other life to speak of, no partner, no family, and few friends who weren’t connected to his demi-monde. He was disillusioned with the media he had once been a part of because it so rarely questioned its own questionable narratives.

By the time he’d had his first drink, vague thoughts of self-help he sometimes nourished had gone out the window. Maier felt impotent. Perhaps he should quit his job, retire from the detective business and work in a bar. He spent almost all his time in bars anyway. Perhaps he should blow the rest of his savings on a couple of months of Cocaine Carolina on the Kiez, drifting through the after-hours clubs with other happy souls like himself. He felt like he’d worked enough. Loved enough. Seen enough, done enough.

When he looked in the mirror, his inner life was on full display, spotty skin, shoulder-length, greasy hair from another age, deepening lines in his almost gaunt cheeks, his green eyes dulled by booze, self-inflicted monotony, and isolation. Wasn’t this exactly the place private detectives were meant to occupy?

His cell phone rang. Maier retrieved his battered Nokia from a two-week-old pile of tired underwear that lay scattered around his fetid bed.

“Maier,” he said as a way of answering.

“Morning, Maier. There’s a job. Time to rejoin the family,” his boss Sundermann said.

Maier grunted at Sundermann, tempted to throw the phone through the closed window at the sun.

“I don’t have a family.”

“Yes you do.”

“What, some cousin I have never heard about wants to suck away the last shreds of kindness I have in me?”

“No Maier, we’re your family. The family of noseys. There’s a job, and you and Mikhail are on it.”

Maier grunted again and coughed up the phlegm of a heavy smoker twice his age. God, he hoped he wouldn’t be around at 96, drooling like a fool, unable to remember the good times. He could barely recall them now. He was tempted to laugh but remembered that Germans usually went to the basement to do that.

“Time to take a trip down memory lane, Maier.”

“I have just been there. It wasn’t good.”

“Stay morose, Maier, it doesn’t suit you.”

“Nothing suits me right now, Herr Sundermann.”

His boss paused. Perhaps the owner of Hamburg’s most prestigious detective agency was hung-over too. It was possible, though it would hardly be the result of a three-day Campari Orange binge. Sundermann had the sensibilities, connections, and wherewithal to live it up in the more salubrious social circles of Germany’s second city. He wouldn’t be sipping crushed insects.

“That’s why I put Mikhail on the job with you. You know, you train him and he covers your back.”

“You are telling me I am losing it?”

This time his boss did not hesitate.

“You’ve lost it, Maier. And no one regrets that more than the family. And no one’s blaming you, the last case was…difficult.”

Maier sat on the edge of his bed and looked at the holes in his dirty socks, not sure whether to feel rage or sorrow. Sundermann was a man of few words, so this should have meant a lot.

“Emilie Ritter just called us. Her husband is missing, presumed dead.”

Maier sat up and coughed past his phone. The mention of Emilie Ritter had jerked him back to half-life.

Fuck memory lane.

“I know that. It was in the papers. It had to happen one day. Combat journos have a high mortality rate. That is why I became a detective, remember?”

“Then you also know he wasn’t shot by a sniper. Funeral’s on Tuesday in Berlin. At the dome. Ritter really was something. A good German.”

“I know that too, I read the papers. National hero killed in boating accident. Nation in mourning for our greatest post-war photo journalist. I am with it, Herr Sundermann.”

“Good to hear that, because Ritter was seen alive and well in Bangkok a couple of days ago. And that’s not in the papers. It’s what his wife says.”

Maier felt sick. His bedroom started to turn.

“I’ll be there in an hour.”

“Good man.” Sundermann chuckled and then hung up.

“I doubt it,” Maier answered to no one but himself.

BERLIN, GERMANY, NOVEMBER 2002

DEATH AND GLORY

Maier stood by the front pews in the Berlin Cathedral, the Berliner Dom as the Germans called it, wearing his only suit, fresh from the dry cleaners and a little frayed around the edges. He tried to take in the whole damn travesty, sure that Martin Ritter would never have wanted this. It reeked of state funeral.

The world was desperate for heroes.

Ritter had grown up in Berlin and he’d be buried here. Maier doubted a journalist had ever been awarded a service in this Kaiserzeit edifice. Everyone from Nina Hagen to Oliver Kahn was milling round under the church’s huge domed and frescoed ceiling amidst the quiet cacophony of several hundred subdued voices. Maier felt quite alone amongst the hushed chunks of glitterati gossip. Of course, he felt alone. He was alone. He was a lonely drunk, feeling sorry for himself.

His new partner and one-time assassin for hire Mikhail had disappeared into the VIP funeral crowd. The Russian was surprisingly agile in his black tuxedo, which added a touch of sophistication to his camp-thuggishness. He wore his shoulder-length, gray-blonde hair with the clout of an aging sports star. He had the airs of an eastern Mike Tyson who read Bulgakow on Quaaludes. He was the heaviest, most dangerous man on the premises. Probably. On the periphery of the occasion, Maier had spotted other men used to wet work – muscles straining in a couple of conservative suits, right by the doors, the only spot it was almost acceptable to be wearing wrap-around shades. The two looked too fashionably dangerous to be German.

Americans perhaps.

Maier remembered Ritter, the celebrated conflict photographer from several conflict zones, a rather intense young man with plenty of brooding charisma, a quick dry wit, and an uncanny ability to make good career moves. The two men had never worked together, but they had bumped into each other in Kashmir, East Timor, and Cambodia— Asian hells Maier had covered as a war reporter for DPA.

They’d known each other casually in Hamburg, with Martin and Emilie dropping by Maier’s apartment a few times to drink copious amounts of vodka and exchange war stories. They’d never gotten close. Probably because Maier had liked the German photographer’s French wife more than the man himself, and she too had seemed rather positively inclined towards the older writer. But those sentiments had never been articulated and their association lay ten years back.

As he looked at Ritter’s coffin, the detective was acutely aware of time passing. Every day the finite became more certain.

The black casket stood a little to the right of the altar. Everyone kept their distance, perhaps because it was empty. Following the mysterious destruction of the deep-sea fishing yacht they’d been traveling on, neither Ritter’s body, nor that of his long-time side-kick, cameraman Frederick, had been recovered.

Maier pushed a few graying strands of hair from his face and smiled to himself, ever so slightly, so as not to upset the solemn atmosphere. He was glad to have left the war business. Happy to be a living loser. Nowadays, he merely joined little wars, involving just a few people and a limited number of dirty secrets and atrocities that could be examined, dissected, analyzed, and occasionally resolved without the immediate risk of severe injury or death. Well, not altogether without risk. Maier had no death wish. He thought of himself as just moderately self-destructive. Despite his depressions and misgivings, he had miles of crushed insects ahead of him.

He drifted off into daydreaming about the good years he’d spent on the front lines, amongst men of violence and infinite sorrow. Those were times past, and he was alive. And for some reason, Martin Ritter, who’d never stopped pursuing just one more shot and one more story in the cold hearts of men, was not.

Officially at least.

“Hallo, Maier, it’s been a long time.”

“Hi, Emilie.”

For once, Maier’s usually decent social skills evaporated as soon as he’d gotten past the formal greetings. Emilie Ritter was sadly radiant, dressed in an elegant black pinstripe suit, a pillbox hat with a black veil partly obscuring her tanned and drawn face, a simple gold chain on her right wrist, and a conservative timepiece on her left. The shoes, all pointy black leather, needed spurs and served as the piece de resistance of her outfit.

In her younger years, Ritter’s wife had been a bit of a rock-n-roller, a countercultural type who’d liked to flaunt protocol. In the 90s, she’d worked for an organization helping Palestinian refugees. She’d been a cool, honest, and fierce activist, though not quite as risk dependent as her younger and brasher husband.

Despite the somber light and the occasion, Maier could see that Emilie looked well. She was almost as tall as him, lithe and straight shouldered. She carried herself like someone who swam a mile a day. Every day. Her grey eyes had lost a little of their wicked sheen as she gazed through the short veil at the detective. Their meeting, the first in a decade, sent a small shock wave down his spine and he wasn’t sure why. He hadn’t felt interested in women in a while. He’d been too drunk.

He smiled politely, trying to remember what his face might look like to assemble it appropriately.

She held out her hand and grinned without happiness.

“You’re looking…good.”

The detective shivered into his shirt. She knew he’d blown it, that he was past his sell-by date. Everyone knew.

Maier forced a smile and scanned past Emilie, trying to get a sense of who was watching him. Too many people. Clearly, he was paranoid. He tried to calm his breathing and focused on his client.

“Thanks for coming. I appreciate it. I take it you are working for me,” Ritter’s wife offered.

“Yes,” was all Maier said.

“I appreciate that too. I didn’t know where else to turn. You were my first and only choice,” Emilie added.

Maier suppressed the urge to cough alcohol-laced bile into Berlin’s most hallowed venue. Trap, was all that went through his mind, though he couldn’t put his finger on the how and why just yet.

“Yes,” the detective mumbled once again.

“Let’s talk later when this travesty is over and you’ve sobered up. I’ll pop over to Hamburg,” Emilie said, dry ice in her voice. She raised an inquisitive eyebrow beneath her netted veil, “You’re still up to this kind of thing, aren’t you, Maier? You look a bit… lived in. What happened to you?”

Maier managed his second smile of the day.

“Yes. I am still the best. I just don’t go to war anymore. Leave that to the kids. They are better with prosthetics and funerals.”

He hoped she would catch the irony. But Emilie just looked bitter. Maier had lost his tact too.

“You don’t look your best, Maier. But your Herr Sundermann assured me that you and your partner can deal with extreme investigations. I suspect the fact that Martin is not in that coffin over there and that he might still be walking around without feeling the need to get in touch with the woman who loves and adores him, is just such an occasion.”

Before he could think of something witty, severe, or at least appropriate to say, she’d turned and elegantly floated across the marble floor to chit-chat with the surgically enhanced mistress of a former German president who greeted her with the professional smile that belonged exclusively to wealthy vampires. Not Maier’s world. Not anyone’s world.

Maier hoped his own deeply lined and worn face had communicated some degree of the genuine warmth he still felt towards the French woman. But he couldn’t be sure. Of anything.

At least she hadn’t noticed his missing fingers or their replacements. Maier was still shy about his loss of digits. The prosthetics, however useful, were making him more freakish than he cared to be.

It was almost time for a drink, he thought, sweating, aware of his own faint odor that appeared to become more pervasive with each clusterfuck catastrophe he lived through. Maier nodded to himself like one of those plastic dashboard dogs so popular with a certain class of Germans and retreated to the back of the church.

Being a little further from godliness would make him feel more comfortable.

One hundred and fifty kilos of Russian super-power sidled up next to the detective. “Some strange people here.”

Maier turned towards Mikhail. “You mean the celebs? Ritter is a national hero. He went where no man has gone before. Over and over again. I didn’t like him too much, but he was the real deal.”

“I saw you talking to his babushka just then,” Mikhail said. “Watch your body language, Maier. Obvious that you’re still fond of her.”

His new colleague was also sweating, despite the cool temperature inside the Dom.

Maier grinned defensively.

“Hey, that’s the first time you’ve smiled since you failed to kill that pig, your father,” Mikhail added.

“So, what of strange people?”

“Oh, I don’t mean the beautifully loving, famous people. It’s the cold-hearted males by the doors that caught my interest. Definitely not German security. Americans, no sense of humor. Hardly friends of war reporters,” Mikhail said. “Asked one of them for a light. Told him I was from Kazakhstan and had spent years on the world’s battlefields. He didn’t ask what battlefields. He didn’t care. Had the feeling he was trading in darkness. But restrained. A guy used to do wet work under strict orders. These are interesting times, Maier. Those doorstoppers are messengers of the new game, the one of the nine-eleven world. They made me feel old school.”

“You are a romantic, Mikhail.”

“Yes, I’m a proud and gay Russian. But I’m a pragmatist too and we’re working, not mourning. As are the fashionable doormen.”

“You have your camera?” Maier asked.

“All done,” the Russian grinned.

BANGKOK, THAILAND, NOVEMBER 2002

WET WORK

The room was small and windowless with cameras stuck in the high corners. The concrete floor was smooth. It smelled of old and new wars. Ritter had set up his tripod opposite the bench that the HVD, what they called the high-value detainee, was tied to. The space between them felt airless, but that was an illusion. Everything was an illusion. That’s why he was there. He’d be the first to capture the illusion, the fallacy.

Welcome to the end of the world. Another end. There were so many. But this was different, dark matter of a new school. Ritter was in a whole new world here, a political space that was being carved out as he pulled his lens into focus, a space that would never go away again. Not in his lifetime anyway. He felt detached, kind of at ease, but also wired to the max, a constant quiet shiver passing through him, licking at his core. This was the next level. A Western nation letting go of so much— dignity, pride, aspiration, perhaps even hope.

The two Americans, Dobbs and Williams, were in shirtsleeves, not nearly as detached as Ritter.

A farmer’s kid from Ohio fighting the good fight, Dobbs was handsome in the way men in fashion catalogues were handsome— smooth as a polished rock face and instantly forgotten. Ritter knew Dobbs from Afghanistan. The photographer was working hard on becoming his current jaded self then and Dobbs had long been connected to the dark side of heroin, girls, and undocumented renditions.

A versatile guy. Dobbs had been chosen for his zeal and commitment as well as for his impunity. They’d called him Mr. Innocence out there.

Williams, a much smaller man with office posture and thinning hair, was a psychologist. He had some medical skills, if not ethics, but he was clearly being led. Dobbs called the shots and Williams looked like the kind of guy who would chew through his own arm for his master. He was here to make sure that the prisoner didn’t die or go insane as a result of the enhanced interrogation techniques they employed. Williams was also the intellectual back-up of the project. It was his organization, the American Psychological Association, that provided the intellectual rationale for turning men into meat.